Text

Deleted sections from the essay in order to reach the wordcount

The education provided by the taxidermy in the NHM is minimal really, especially compared to the Hornimans or the Grants Museum, especially given their relative footfall – which is a problem. This leads to these creatures being separate from the ‘human world’ as they aren’t contextualised with what visitors know. The greatest book ever written is just words put in order, but the qualifying worth is in the craftsmanship, how those words are attached to one another. This isn’t to say that we scrap anything that isn’t a dioramic depiction of reality, but rather that we make more of an effort to educate, or elicit a response rather than simply witness. The mass extermination of American bison was something that was instigated by white colonialists, but it was only when taxidermy bison were taken to Washington did (white) people actually start to rationalise, and to care.

The guide takes you through vacuum sealed air and temperature-controlled rooms, explaining the pay per view specimens. Only when you get to the main specimen room does it hit you, not just the smell of decay and preservative fluids, but the attempt to document everything this side of the last ice age; mammals, birds, reptiles, fish, amphibians and invertebrates of all sizes and origins. Lying in the centre of the room is a giant squid called Archie - shadowing Darwin’s specimens in a locked 2” by 6” cabinet.

Collected on his trip to the Galapagos, these are marked with yellow dots on the top of the jars, signifying that they are the frame of reference for a then unknown species, the OG, the original genus. On the wall, there is a list of pager extensions to each of the head scientists, for each area of the animal kingdom –

The synopsis of the BBC Radio 4 programme titled ‘L’origine de L’Origine du Monde’ (2016) states:

‘L'Origine du Monde is perhaps the most notorious and explicit painting housed in a public museum…Its first owner was Khalil Bey, a wealthy art collector and diplomat for the Ottoman Empire. Visitors and dinner party guests would be led to his dressing room and towards a green curtain:

"When one draws aside the veil, one remains stupefied to perceive a woman, life-size, seen from the front, moved and convulsed, remarkably executed ... providing the last word in realism".’

There isn’t a logically plausible way that all art can be seen when it needs to be seen, but this point highlights that the creative world requires radical upheaval at the upper levels in order for the equality wanted to actually function. Self-proclaimed working class academic Lisa Mckkenzie states that ‘Until the middle class let their talentless offspring fail, the arts in Britain are doomed’, and one could argue that this issue of class privilege strangles not only the creative world, but prevents the reformation needed for the betterment of social issues throughout our modern culture. Taxidermy can be brought out of the backroom, to be used as another avenue in which to directly attack not only issues like global warming, but also establishments including those in the artistic world - with the antithesis of what humanity appears to have become, the organic matter we boil down to.

Education and action are the key elements to social progression, but for these a level of confrontation is required, which is why those without a need for change aren’t the right people to control education or indeed artistic institutions. Natural aspects of the world we live in are easier to avoid now as we exterminate species, expand cities, change our bodies and destroy forests, so one could easily argue that we need to employ preservation as an enlightening or artistic expression to break the systemic faults which take the easy route out

0 notes

Text

Abstract/ Blurb

Using the life and work of radical taxidermist Carl Akeley (1864-1926) as a point of entry, this project aims to query the artistic merit of animal preservation and its future in the modern artistic lexicon. As opposed to stagnating as a remnant of history, the act of taxidermy is still executed by a growing number of hobbyists and interested parties alike, however the housing and public display of preserved animals has waned, leaving fixed instalments such as those in the Natural History Museum gathering dust, slowly degrading.

Spare the few focussed exhibitions used to educate tourists, taxidermy is seldom seen in an artistic sense. Akeley’s work, which is in great part responsible for progressing animal preservation away from being an anthropocentric ‘furniture’ craft and towards a narrative and didactic production, allows us to scrutinise taxidermy practices as not exclusively based in pride, rather, as a viable artistic form and material – a claim supported by the works of Claire Morgan and Iris Schieferstein.

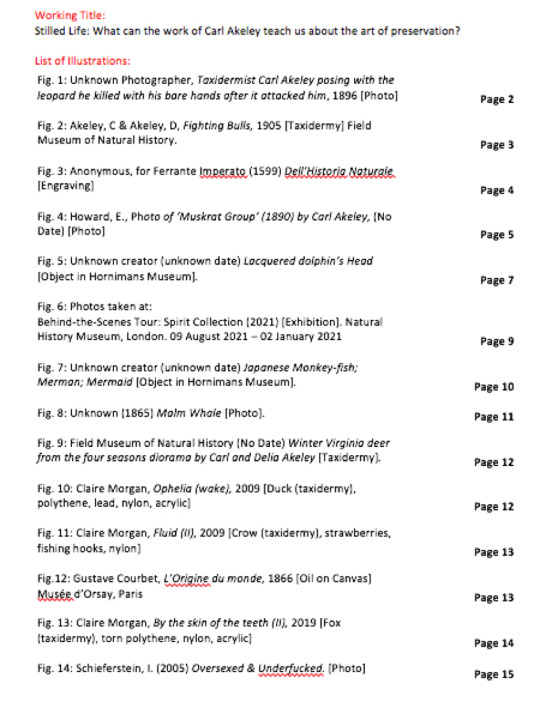

(Fig. 1: Unknown Photographer, Taxidermist Carl Akeley posing with the leopard he killed with his bare hands after it attacked him, 1896 [Photo])

Akeley Synopsis

‘Mounted animals were already obsolete as a viable form of zoology when the Natural History Museum (London) opened — researchers behind the scenes were increasingly focusing on the living animal, as stilled, frozen bodies continued to educate the public. It was precisely because taxidermy had become the bankrupt estate of scientific research that these objects entered the field of artistic reflection.’ (Lange-Berndt, P., 2014)

Taxidermist Carl Akeley (Fig. 1) was born in rural Clarendon, New York state, in 1864. Growing up in the Gilded Age and surrounded by a culture of outdoor sports like hunting, Akeley would become known for applying his artistic abilities and obsession for realism to revolutionise the practice of taxidermy. In contrast to the longstanding status quo ‘upholstery’ of an animal (usually a skin stuffed with inexpensive materials), Akeley earned his title as the ‘Godfather of modern taxidermy’ by being the pioneer behind meticulously sculpting the structure of an animal in modelling materials, then mounting the skin onto the cast, giving the animal an uncanny resemblance to its extant form.

This project will look at his work as a form of art, and less at the person he was or became; however, it is important to consider the suffering he was responsible for; that although he established a painstakingly accurate way to depict natural evidence as art, he was also a product of his times – a museum salaried hunter responsible for the availability of ‘voucher specimens’ (a specimen that serves as a verifiable and permanent record of wildlife by preserving as much of its physical remains as possible). Already vulnerable - and therefore valuable - animals were collected on excursions funded by institutions, although one could argue that Akeley and his colleague/ wife Delia (along with their cohort of assistants, artists, photographers and writers) were the best to employ, for their eccentricity and craftsmanship allowed them to best depict any animal subject to this practice, making something appear so convincingly real that no-one would think one was involved at all – essentially making taxidermy an artistic form, despite it still not being accepted as such.

Fig. 2: Akeley, C & Akeley, D, Fighting Bulls,1905 [Taxidermy] Field Museum of Natural History.

Akeley not only worked during the time when photography and film was being used (albeit in a novel capacity) he also helped to pioneer this craft whilst still working for museums.In the modern world, the majority have easy access to photographic appliances, and with dedicated channels to view documentaries on it is easy to dismiss taxidermy as an antiquated craft, although one should consider that without the concept behind preservation, there would have been no motivation to create the motion picture camera used to film the first documentary ‘Nanook of the North’ in 1922.The idea of capturing the wild was held in higher regard than the blood - sport of hunting to Akeley, and in later life, according to Alvey (2007), he retrospectively indicated that:

"the camera hunters appeal to me as being so much more useful than the gun hunters." The latter had amassed a great deal of knowledge about the wildlife of Africa, but left no record of it, while the "camera hunters" have left a photographic record - "and when their game is over the animals are still alive to play another day."

Alvey, primarily looking at the photographic and filmic legacy of Akeley, continues and comes to highlight a key component of his character noticeable in many, if not all ‘great artists’: the obsessive drive to ‘capture’ the natural in a mimetic form; applying “André Bazin's proposition that at the root of the representational arts is an "obsession with realism" or in his famous shorthand, a "mummy complex.". This is a central factor whichmakes Akeley suitable for the discussion of taxidermy as an ‘art’. As the figurehead of modern preservation, he transformed what was primarily a practice following the rules of fast fashion into a creative craft, and instead of anthropocentric pride, the depiction of reality was key. In pairing his technical mind with a desire to capture an ‘as in life’ version of what he witnessed in the biological world, he became the de facto natural curator, his fame perpetuated by his mania.

retrospective on taxidermy

Historically, taxidermy has always had a quintessential essence of egocentricity. One could say that the act of animal preservation has fallen somewhat into the same category as murder, where an individual has the power of a god; whether taking a life, or curating death’s trophies. At the same time, taxidermy has also always been something to visually fascinate, the key to any form of art, which is why taxidermy was popular for wealthy collectors as something that they could contextualise out of self-interest rather than facts (a practice commonly seen in western religious art).

Fig.3: Anonymous, for Ferrante Imperato (1599) Dell’Historia Naturale[Engraving]

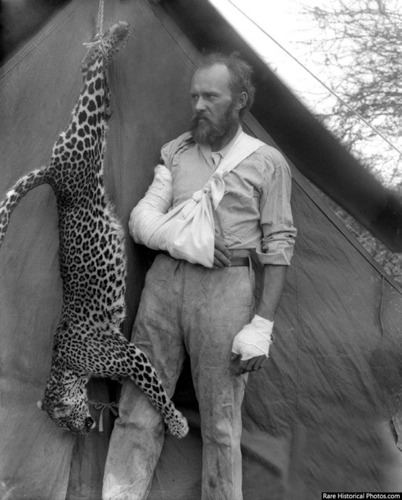

The Wunderkammer (or ‘cabinets of curiosities’) of the 1400s onwards formed the basis of what we now know as the ‘museum’. Facilitated by colonialism, the upper classes could entertain guests with tales of obscure objects and fantastic beasts, oftentimes bolstered by false self-insertions, within dedicated spaces and even whole rooms, as depicted in fig. 3. (Aloi, 2021). Even today one can see hunting trophy rooms in films and programmes as an extension of this practice, but Aloi suggests that generally speaking:

“…during the 18th century the focus shifted. The rise of science as a defined discipline meant that collections could no longer just represent the wealth and intelligence of the owner, but that they needed to make sense of the world we lived in a more objective way. This is what the human skull we see on the top shelf of [Domenico] Remps’s cabinet anticipates—an existentialist urge to understand life and the knowledge that despite the wealth one might accrue, death will at once take it all away.” (Aloi, 2021)

Thus, personal endeavours and collections of favoured objects; hunted, stolen and bought were purchased by institutions, then curated for the public. The nature of these cabinet collections meant that the line between the artistic and scientific would overlap greatly, false preservations and genuine artefacts housed together would be compartmentalised. Just as art galleries specialise their interests to say, portraits or modern art; nature, science and art were sorted via institution. Due to the components of taxidermy being largely animal matter, they would have been classed as scientific, or indeed just kept for ‘scientific study’; as preservations of nature, they were kept with seashells and archaeological bone fragments in the drawer marked ‘world science’.

Preserved animals have always been popular attractions and opportunities to make a spectacle of humanities’ ‘others’ – but this schism between human and non has been exacerbated by time and modern life, our individualism removing us from a system we are biologically grafted to. To amputate taxidermy from the context of visual culture completely is like taking the skull out of Remp’s cabinet, it eliminates the potential energy by imposing exclusivity. Although one could say that museums allow free access to a resource, they also falsely preserve the concepts of the pieces they house. Akeley himself evidently thought it best that the specimens he would deliver for institutions like the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago would provide the public with ‘as in life’ depictions of animals and their habitats, potentially recognising the importance of context within his craft (or arguably the product of his mania for detailing the tangible animal), which lead to many institutions following suit, producing inspiring displays from the addition of context counteracting the anthropocentric collector atmosphere of museum menageries.

Fig. 4: Howard, E., Photo of ‘Muskrat Group’ (1890) by Carl Akeley, (No Date) [Photo]

Akeley’s craft, for example,Fig.4, raises the argument of whether a faithful depiction is less ‘artistic’ in preservation, but it could be contended that, in fact, to meticulously consider every detail of all the subjects within a recreation is as much an artistic endeavour as a scientific one. Take for example, how the anatomical depictions of the human body existed as art after the ancient Greek Galen’s works (who had only dissected other animals), until Andreas Vesalius’ illustrated book disproved theories held for over a century. Art and science exist with a similar symbiosis as humans and nature, to undercut one side would be damaging the other, when in combination truly amazing things can be created: in Akeley’s dioramas, there is biotic artistry as well as artistic science

science vs art

Primary research: Museum Trips

Within this section of the project, I report the experience of visiting the Hornimans museum and the Natural History Museum (both general admission and theBehind-the-Scenes Tour: Spirit Collection).

The situation that I found myself in when visiting the Hornimans museum for the second time (location drawing) highlighted to me the importance of taxidermy in the artistic world, mainly for its benefits in improving artistic execution and the first-hand opportunity it provides as a grotesque reference image. It also emphasised that like the Grants Museum of Zoology, there is a presentation style to the taxidermy and objects within more aligned to artistic institutions than historical ones– which opens a discussion on whether this is an organization of artistic curation or colonial practices. For example, Fig. 5, a Japanese painted Dolphin skull, whether kept for its aesthetic appeal or an empire obsession with ownership (or both) is not publically known, but it certainly doesn’t serve a scientific purpose, more an anthropological one. It highlights creative decisions made by people not nature, and like many of the Hornimans’ pieces, curiosities and taxidermy occupy a similar space as they would have in the Wunderkammers of the 1400’s.

Fig. 5: Unknown creator (unknown date) Lacquered dolphin’s Head [Object in Hornimans Museum].

A large majority of the animal exhibits in the main room are presented as educational, separated out by taxonomic classifications or animal characteristics, but it has to be acknowledged that this museum was once just a huge wunderkammer, although they should be commended for the repurposing of empire mentality as education. Another aspect that became apparent through viewing the collection was that taxidermy is an art form which requires the craftsman to do so much, that there should be no sign that they were there at all; The artistic merit in taxidermy could be argued as being in the essence of nature, rather than in creating something wholly new.

But this does raise issues, such as art acting as a justification for suffering, which applies hugely to the practice of huntingfor mounts. One could propose it as a great way to learn the forms of an animal by using a someone’s craftsmanship, in conveying the essence of a living creature, but in doing so how detached are we from the suffering of the animal? A counter argument could be that this would be more of an issue if taxidermy remained a primary resource, as opposed to the modern viewer mostly being exposed to older specimens, not likely killed in their lifetime (although this argument leads to the conversation that distance from an event doesn’t change the nature of the incident). However, in ethical taxidermy, the animal died regardless of human interaction, or was unintentionally killed, but it’s pelt will be immortalised for educational or aesthetic referential means.

As a species, we try to distance ourselves from the fact that we are animals by saying things that seemingly qualify us as higher, or more than an animal. In ‘traditional’ taxidermy, one ends up quite surreally using an animal’s death to prove we are more sophisticated beings, through the method of killing - an animalistic act, but instead of survival, the goal was bragging rights. Western taxidermy was conventionally the merchandise of blood sport. With this in mind, it is apparent that the product (taxidermy) outlives the name of the hunter; we look at taxidermy to see the animal, in the same way that there are truly wonderful works of art independent of our knowledge of an artist. Science requires empiricism, facts and figures, names and dates, whereas art only needs to evoke something within a person to be considered art, taxidermy then, is stuck between states of existence.

The education provided by the taxidermy in the NHM is minimal really, especially compared to the Hornimans or the Grants Museum – which is a problem. This leads to these creatures being separate from the ‘human world’ as they aren’t contextualised with what visitors know. The greatest book ever written is just words put in order, but the qualifying worth is in the craftsmanship, how those words are attached to one another. This isn’t to say that we scrap anything that isn’t a dioramic depiction of reality, but rather that we make more of an effort to educate, or elicit a response rather than simply witness. The mass extermination of American bison was something that was instigated by white colonialists, but it was only when taxidermy bison were taken to Washington did (white) people actually start to rationalise, and to care.

One component of the problem is that a lot of the creatures in the NHM are immortalised as singularities rather than as narratives, as a blip on the radar with no traction. We are remarkably selfish mammals (the fault of which is both genetic and contextual), wanting things to matter to us whilst suffering from a relatively small ability to rationalise amounts (for example thinking of 20,000 people or 600 rhinos, anything greater than ‘a few’). To see an animal is one thing, but to be able to see the life additional to the skin strenuously placed on a mount, is something with a lasting effect. This would lend itself not only to the theory that taxidermy should be viewed with the same eyes cast towards art conveying a narrative, but also to the argument that recognising and exploiting taxidermy as an art form forces humans to actually care about the natural world, and why avoiding the gruesome root of our evolution is easy when institutions make it easy (acknowledging that humans are perfectly capable of this without help) – without challenges, we are not the apex predator of the natural world, rather, we are lower than any animal on earth.

Fig. 6 (A)(B):Photos taken at:

Behind-the-Scenes Tour: Spirit Collection (2021) [Exhibition]. Natural History Museum, London. 09 August 2021 – 02 January 2021

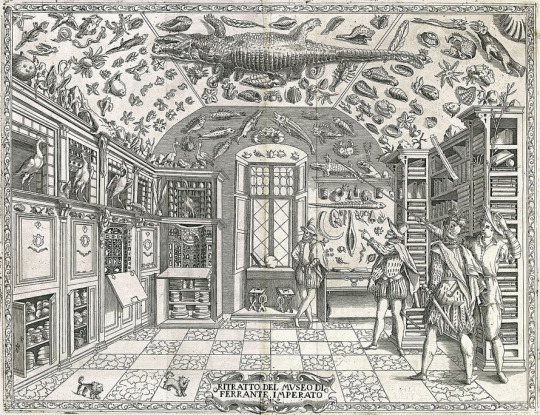

The ‘Behind the Scenes’ exhibit in the Natural History Museum (Fig. 6 (A and B)) allows paying members of the public to go into the scientific belly of the whale, where researchers attempt to decipher the codes of life with DNA swimming around in now reddening and yellowing specimen jars. The guide takes you through vacuum sealed air and temperature-controlled rooms, explaining the pay per view specimens. Only when you get to the main specimen room does it hit you (not just the smell of decay and preservative fluids): the attempt to document everything this side of the last ice age; mammals, birds, reptiles, fish, amphibians and invertebrates of all sizes and origins. Lying in the centre of the room is a giant squid called Archie - shadowing Darwin’s specimens in a locked 2” by 6” cabinet.

Collected on his trip to the Galapagos, these are marked with yellow dots on the top of the jars, signifying that they are the frame of reference for a then unknown species, the OG, the original genus. On the wall, there is a list of pager extensions to each of the head scientists, for each area of the animal kingdom – this part of the institution keeps for these specimens so more can be learned from the animals which make up the earth, and where despite our efforts, humans lie. This experience (although obviously marred by the fact that the man guiding the tour is paid by the museum) did allow viewers to rationalise wet specimens as scientifically important, as well as being another visual display of human dominance. This isn’t to say they aren’t artistically important, but that their scientific contributions will always outweigh their creative ones.

The presentation of specimens in both the Hornimans and the NHM rely heavily on the work of Carl Akeley, in contrast to ‘guestimation’ practices, rogue taxidermy and glutton syndrome preservation. However, this is obviously not true for certain examples which predate Akeley, such as the false merman housed beneath the dolphin skull, Fig 7.

Fig. 7: Unknown creator (unknown date) Japanese Monkey-fish; Merman; Mermaid [Object in Hornimans Museum].

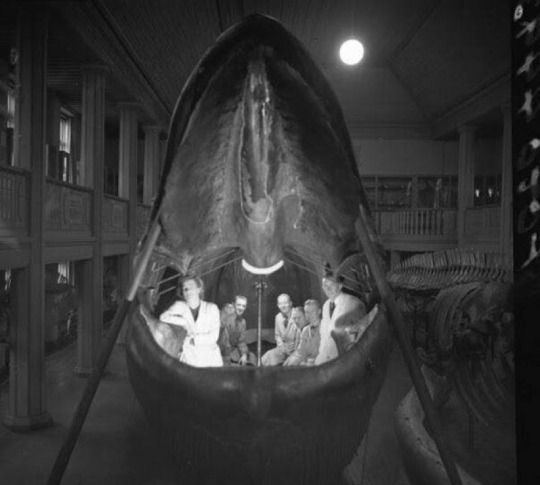

Fig. 8:Unknown (1865) Malm Whale[Photo].

The preservation of false information

- Short section on the human tendency to invest great interest in the preservation of false information, such as of cryptids, or the curiosity element that plays a role in what gets preserved and displayed. That which is ‘one of a kind’, like the Malm whale (Fig. 8), crystal palace dinosaurs, rogue taxidermy or Japanese monkey fish still retain the appeal that drew people to ‘freak shows’ in the late 1800’s, but what role do they serve in the modern world? And can they be seen as artistic objects (e.g. dolphins head) or is it just another excuse to keep misinformation around (and how damaging is this)? This section provides a good contrast to one of Akeley’s most famously accurate works, ‘four seasons’, and why bad taxidermy is fundamental to the discussion of taxidermy as a progressive art.

Akeley’s four seasons vs the modern artist: the progression of taxidermy art:

- Akeley’s four seasons, a set of dioramas depicting Virginia deer in winter, spring summer and autumn, seen now as a benchmark for taxidermy due to not only Akeley’s skill in composition and execution, but also due to the fact that he and his wife at the time Delia, organised the hand rendering of suitable landscape paintings for the backgrounds and individually creating thousands of leaves, fauna and flora to create the dioramas. Arguably a result of Akeley’s obsession for the real and complete depiction. This diorama set is a good piece to compare to modern artist Claire Morgan (and look at how the modernised world allows us to go further than Akeley, referencing his own methodology), then lead through to Iris Schieferstein and to possible passing mention of Joel peter Witkin and Diane Arbus (for a focus on the argument of otherness) onto Gustave Courbet.

Fig. 9: Field Museum of Natural History (No Date) Winter Virginia deer from the four seasons diorama by Carl and Delia Akeley.

Fig. 10: Claire Morgan, Ophelia (wake), 2009 [Duck (taxidermy), polythene, lead, nylon, acrylic]

Fig. 11: Claire Morgan, Fluid (II), 2009 [Crow (taxidermy), strawberries, fishing hooks, nylon]

The Other

Fig. 12: Gustave Courbet, L’Origine du monde, 1866 [Oil on Canvas] Musée d’Orsay, Paris

French realist painter Gustave Courbet’s work is known for being socially charged and habitually rooted in tangible human struggles; depictions of inequality, mental illness and the working class through pieces like ‘A Burial at Ornans’ (1850) or ‘The Desperate Man’ (1845) were exhibitions of literal realism, rather than the purely conceptual kind. His work often sparked controversy due to the context that it found itself in (during a tumultuous time in French history), but Courbet’s ‘L’Origine du monde’ (Fig. 12) or ‘The Origin of the World’,is notoriously his most censored, regardless of the relatively small amount of time it has been available to view by the public. Despite being a masterpiece, its existence it has been subject to the patriarchal opinion of what aligns to the socio-cultural beliefs around what can or can’t be openly displayed.

The synopsis of the BBC Radio 4 programme titled ‘L’origine de L’Origine du Monde’ (2016) states:

‘L'Origine du Monde is perhaps the most notorious and explicit painting housed in a public museum…Its first owner was Khalil Bey, a wealthy art collector and diplomat for the Ottoman Empire. Visitors and dinner party guests would be led to his dressing room and towards a green curtain:

"When one draws aside the veil, one remains stupefied to perceive a woman, life-size, seen from the front, moved and convulsed, remarkably executed ... providing the last word in realism".’

The first part of this oil painting’s existence consisted of it being a peep show party gimmick, and since being installed in modernity it has either been proclaimed mainly as something to ogle at, an opportunity for men to spectacle at the ‘other’ or discuss self-perpetuated controversies. Although Courbet is now heralded as a prime mover of the realist effort, the fact that ‘L’Origine du monde’ spent the majority of its existence hidden or in a state of quantum superposition means that it didn’t have the effect it could have had on the art world. The impact it has is reliant on the social context it exists within, and one could posit that currently, as in 1866, most people have a culturally ingrained distaste for seeing the female genitalia in a non-sexualised way, in a manner similar to how we judge the exhibition of animals revealing the common denominators between humans and nature, the most apparent being that of suffering and of death.

Fig. 13: Claire Morgan, By the skin of the teeth (II), 2019 [Fox (taxidermy), torn polythene, nylon, acrylic]

To support this theory, one may look at how we show a general acceptance as a wider society of the textbook, clinical vagina or the sexualised, pornographic vagina, in the same way that we accept museum taxidermy - or the caged animal, electing for the exposure to it; but somehow people are hypocritically disgusted by actual reality. One could argue that the patriarchy and those most influenced by it see women and animals as the others in theirworld, and claim ownership over them, to spectacle and exploit the preferred parts; pornography and zoo’s, voyeurism and hunting. Perhaps in our social treatment of women in society as ‘less than men’ or by inference, closer to animals, society has assigned honest depictions of female genitals (acknowledged by Courbet as the root of humanity’s existence) to the same class as taxidermy, the stilled version of the ‘other’, ancestrally or current.

Although the context in which these pieces were housed would greatly influence their impact and reach, taxidermy, like or as art, can be a way to celebrate an animal, or to highlight an issue, such as in Morgan’s ‘By the skin of the teeth (II’), Fig. 13; similarly, the human form as in Courbet’s work, or a combination of taxidermy and individuals as in Schieferstein’s ‘Oversexed & Underfucked’, Fig. 14, can be used to confront humanity’s ugly nature with nature itself.

Fig. 14: Schieferstein, I. (2005) Oversexed & Underfucked. [Photo]

In relation to the discussion of preservation and the immortal dead, rather than what is principally described as an obvious painting of a woman, the pallid tones of a corpse creeping into the canvas in ‘L’Origine du monde’, the hue of oxidising meats on a supermarket shelf, remind one of a Vanitas painting, or Memento Mori, designed to remind the viewer of mortality. Courbet, it could be posited, is explicitly telling the world “our biological foundation relies on this complex biological structure and without it we are nothing”. Despite this important idea that should be integral to the human psyche, the exposure of ‘L’Origine du monde’ is controlled by persuadable people aiming to keep everyone contented whilst remaining ignorant to the fact that it should be used as a tool of questioning ‘why does something natural make you uncomfortable?’

The utilisation of something we avoid or feel awkward around, i.e. acknowledging our animal roots, a fear of death or the relationship we have to one another in an age of individual struggle, cultivated by neo-liberal normalisation and confusionism is required in a world numbed by superficial pleasantries. Just as some female artists are utilising their bodies to force society to confront objectification and similar issues,ethically sourced taxidermy can be a way to enlighten and enforce an audience’s relationship with the animal kingdom.Instead of passively viewing a distorted male version of the female body, museum specimens or seeing a perfectly functioning zoo or documentary animal, flesh of all kinds can help conceptually rationalise or contextualise a subject in an applicable way.

However impactful the piece is now, it’s initial force was stolen from it, just as how natural art is stored in the backrooms of museums and great talent is boiled down in the oversaturated soup of social media. Female creators of art especially can relate to this essence of potential energy(taxidermy itself seeing a growing number of female practitioners respective of its male centric roots (Stuffed, 2019)) such as photographer Francesca Woodman (b.1958 – d.1981) or painter Gwen John (b.1876 - d.1939) who died either unacknowledged or overshadowed, and while their work is now critically and publically celebrated, there appears to be an inherent problem in the system of assessing art which is governed primarily by the biased (as if this was new information). There isn’t a logically plausible way that all art can be seen when it needs to be seen, but this point highlights that the creative world requires radical upheaval at the upper levels in order for the equality wanted to actually function. Self-proclaimed working class academic Lisa Mckkenzie states that ‘Until the middle class let their talentless offspring fail, the arts in Britain are doomed’, and one could argue that this issue of class privilege strangles not only the creative world, but prevents the reformation needed for the betterment of social issues throughout our modern culture. Taxidermy can be brought out of the backroom, to be used as another avenue in which to directly attack not only issues like global warming, but also establishments including those in the artistic world – imagine a preserved London fox titled ‘this machine kills fascists’ - with the antithesis of humanity, the organic matter we boil down to.

Education and action are the key elements to social progression, but for these a level of confrontation is required, which is why those without a need for change aren’t the right people to control education. Natural aspects of the world we live in are easier to avoid now as we exterminate species, expand cities, change our bodies and destroy forests, so one could easily argue that we need to employ preservation as an educational or artistic expression to break the systemic faults which take the easy route out.

consolidation of ideas conclusive remarks

this section is currently being used as a dumping ground that is ideally revisited once all the fundamental information is established in the essay, however some points may be:

- Akeley’s mounts follow the context of the time, the display of voucher specimens, whereas now it’ just as important to combine education with action

- As a material for an art piece, the body of animals have always been used by humans, hairs of brushes, glues and shellac, to name a few. How a material is applied matters, but in this instance how it is sourced is equally important; in ethical taxidermy, an individual is essentially recycling – taking that which is no longer needed and using it sustainably. There are plenty of existing skins and neglected specimens sat in dark rooms around the world, and as an entirely consistent element of life, death will always occur.

- Gunther von Hagen’s museum / joel peter witkins contextualised death and human taxidermy

- (on religious art) If god is the divine creator and a great artist steals, taxidermy is surely using deific as an art material

- Resentment or closet skeletons of history

- The transposition of imagination into something tangible

- Stigmas around taxidermists vs current practice e.g. recycled materials ethically sourced, the banality of evil

- Taxidermy isn’t an intrinsically immoral practice, for example in the cases of deceased pets, ‘taxidermy for the grieving’ or ethical sourcing through roadkill, but it does suffer the connotations with its origins. (Stuffed, 2019)

- A skilled taxidermist might theoretically reimagine a deceased London fox, scarred with road rash, lifeless on a pavement in any position, even in a natural stalking manoeuvre, then it can be used in an art piece, or even taken to schools to educate students. Encouraging this kind of publically accessible ethical taxidermy is actually an opportunity in today’s world, rather than a cruelty or a lack of respect for the dead and although there are outliers who still use blood sports to source their private collections, this is more an issue of the individual rather than the craft. Many creatures, exotic and native, are preserved with natural or insignificant causes of death, the most historically popular example of this is in the death of a pet, or the resident of a zoo.

- Utilitarian and Speciesist Peter Singer states that “in suffering, the animals are our equals”

- Amateur exotica (houseplant colonialism)

- The problem of audiences – those willing to enter a room or buy a ticket have already fulfilled a level of completion in terms of thought process – i.e. a person who goes to see an exhibit on the effect of plastic pollution on animals isn’t going to be spending the rest of their time ramming straws into turtles are they?

- The proposition of a ‘Museum of Natural Art’ is one that could be a brilliant opportunity to praise not only exotic and curious objects rooted in nature, but also that which we overlook on a daily basis - a nature positive exhibition. Despite installations in modern art galleries worldwide, there ceases to be a consistent venue, in contrast to more established institutions (e.g. if you want portraiture you go to the portrait gallery, natural history, the NHM etc.). There are plenty of works being conceived, and even the thousands of unused taxidermy specimens in existing museums could serve to benefit a natural art institution.

It is often suggested in the modern world that we need a ‘reset’, however, one could propose that creating institutions for the new generation who are being held responsible for the correction of cumulative world destruction by their predecessors is a necessary step for actual change. A good example of this would be the topography of terrors, situated in Berlin, which details Germany’s role in world war 2 with admirable self-critique; or similarly artist Darren Cullen’s Museum of Neo-Liberalism in London which satirises and informs the public on the problems of the modern world (viewable here: https://www.spellingmistakescostlives.com/museumofneoliberalism).

An institution using the natural world to its fullest potential would be an active way to make sure that the society we exist in can actually progress with knowledge, rather than just perpetuating the issues prescribed by our current system. It’s far too easy for the impressionable to scroll past a social media post about feminism or the climate crisis and be coaxed in by the flashy redtop opinions of denial and hate – and this isn’t an issue that will be eliminated by the mortality of previous generations; instead we need to make functional decisions to enlighten the populous rather than leave those born into stagnation in a feedback loop. it may be hard to kick against the pricks, but if humanity claims, as it often does, to be of a higher order than animals, it should be easy to create a system in which we actually learn from the things around us. Taxidermy was evidently started in order to create and share stories, albeit from a place of vanity, but this anthropocentric craft now can act as a way to benefit our world, without being so abstract or exclusive as to alienate those excluded from the ‘art’ sphere. It isn’t leftist modern art, or traditional old masters, it (when done well) is as new as it is old. frozen in a state of almost permanence, and by heralding it and repurposing it, we could defrost ourselves from the ice age of anti-naturalism we now find ourselves in.

- Although we now have David Attenborough and 4k ultra HD, we still need to see things first hand, evident from Akeley’s experiences with the mountain gorilla (Akeley, whilst on an expedition looked into the eyes of a Gorilla and had a classic movie moment, hung up his rifle and went on to help the creation of the national park that serves to protect the critically endangered animal)

- public interest (let alone intelligence) has greatly waned in modernity, while ignorance of this fact has only increased (Dunning-Kruger),

- importance of having institutions compensating the lack of educational opportunities is fundamental in the working class (especially when the exposure is lessened by those in power)

- Conclusive remarks on Akeley’s importance in seeing Taxidermy as an art form and how his reinventions should encourage our own. (end of essay should question if ‘art’ is intrinsically inanimate/ non-organic, or if when so much art is inspired by the living world, why taxidermy is still sparsely used– what defines that which is art and what is disposable?)

Note:

(On Designed Outcome)

As in my statement of intent, I still plan to present the final writing in the form of a vintage taxidermy manual, allowing complimentary illustrations to be produced which support and reinforce the contents of the project.

Bibliography:

5x15 Stories (2021) Philip Hoare - Albert and the Whale. April 13. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8aqnOOegl1E (Accessed: 12 October 2021).

Akeley, C., Akeley, D. (1905) Fighting Bulls [Sculpture]. Field Museum of Natural History. Photo available at: https://www.fieldmuseum.org/about/history/carl-akeley(Accessed: 26thDecember 2021).

Aloi, G (2021) Cabinets of Curiosities and The Origin of Collecting. Available at: https://www.sothebysinstitute.com/news-and-events/news/cabinets-of-curiosities-and- the-origin-of-collecting (Accessed: 18 October 2021).

Alvey, M. (2007) ‘The Cinema as Taxidermy: Carl Akeley and the Preservative Obsession.’, Framework: The Journal of Cinema & Media, 48(1), p.23-45.

Anonymous, for Ferrante Imperato (1599) Dell’Historia Naturale[Engraving]. Available at:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferrante_Imperato#/media/File:RitrattoMuseoFerranteImperato.jpg(Accessed: 26thDecember 2021).

Behind-the-Scenes Tour: Spirit Collection (2021) [Exhibition]. Natural History Museum, London. 09 August 2021 – 02 January 2022 (Viewed: 20thSeptember 2021).

Bolger, R. (2021) Bird Taxidermy: the Australian specialists who love birds in life and death. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/sep/30/bird-taxidermy-the- australian-specialists-who-love-birds-in-life-and-death (Accessed: 17 October 2021).

Courbet, G. (1866) L’Origine du monde[Oil on Canvas]. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%27Origine_du_monde#/media/File:Origin-of-the-World.jpg(Accessed: 26thDecember 2021).

Field Museum (no date) About/ History/ Carl Akeley. Available at: https://www.fieldmuseum.org/about/history/carl-akeley (Accessed: October 26 2021).

Field Museum of Natural History (No Date) Winter Virginia deer from the four seasons diorama by Carl and Delia Akeley.Available at: https://fm-digital-assets.fieldmuseum.org/533/846/Z13T.jpg(Accessed: 26th December 2021).

Henning, M. (2007) ‘Anthropomorphic Taxidermy and The Death of Nature: The Curious Art of Hermann Ploucquet, Walter Potter, And Charles Waterton’, Victorian Literature and Culture, 35, p.663-678.

Howard, E. (No Date) Photo of ‘Muskrat Group’ (1890) by Carl Akeley. Available at:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Akeley#/media/File:Akeley's_muskrats_(24092994301).jpg(Accessed: 26th December 2021).

Lange-Berndt, P. (2014) ‘A Parasitic Craft: Taxidermy in the Art of Tessa Farmer’, The Journal of Modern Craft, 7(3), p.267-284.

L’origine de L’Origine du Monde (2016) BBC Radio 4, 25 August 2016. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b07pj824(Accessed: 01 January 2022).

Morgan, C (2019) By the skin of the teeth (II) [Installation]. Available at: https://claire-morgan.co.uk(Accessed: 26thDecember 2021).

Morgan, C. (2009) Fluid (II) [Installation]. Available at: https://claire-morgan.co.uk(Accessed: 26thDecember 2021).

Morgan, C. (2009) Ophelia (wake) [Installation]. Available at: https://claire-morgan.co.uk(Accessed: 26thDecember 2021).

Museum of Idaho (2017) A brief, gross history of taxidermy. Available

at: https://museumofidaho.org/idaho-ology/a-brief-gross-history-of-taxidermy/(Accessed: 17th October 2021).

Schieferstein, I. (2005) Oversexed & Underfucked.Available at: https://www.iris-schieferstein.de/art-kunst/pictures-fotos/(Accessed 26thDecember 2021).

Stuffed (2019) Directed by Erin Derham. Available at: Kanopy (Accessed: 12 October 2021).

Unknown (1865) Malm Whale[Photo]. Available at: https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/malm-whale(Accessed: 26thDecember 2021).

Unknown creator (unknown date) Lacquered dolphin’s Head [Object in Hornimans Museum]. Available at: https://www.horniman.ac.uk/object/object-120496/(Accessed: 26thDecember 2021).

Unknown creator (unknown date) Japanese Monkey-fish; Merman; Mermaid [Object in Hornimans Museum].Available at: https://www.horniman.ac.uk/object/NH.82.5.223/(Accessed: 26thDecember 2021).

Unknown Photographer. (1896) Taxidermist Carl Akeley posing with the leopard he killed with his bare hands after it attacked him. Available at: https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/carl-akeley-leopard-1896/ (Accessed: October 26 2021

1 note

·

View note

Text

consolidation of ideas conclusive remarks

This section is currently being used as a dumping ground that is ideally revisited once all the fundamental information is established in the essay, however some points may be:

- Akeley’s mounts follow the context of the time, the display of voucher specimens, whereas now it’ just as important to combine education with action

- As a material for an art piece, the body of animals have always been used by humans, hairs of brushes, glues and shellac, to name a few. How a material is applied matters, but in this instance how it is sourced is equally important; in ethical taxidermy, an individual is essentially recycling – taking that which is no longer needed and using it sustainably. There are plenty of existing skins and neglected specimens sat in dark rooms around the world, and as an entirely consistent element of life, death will always occur.

- Gunther von Hagen’s museum / joel peter witkins contextualised death and human taxidermy

- (on religious art) If god is the divine creator and a great artist steals, taxidermy is surely using deific as an art material

- Resentment or closet skeletons of history

- The transposition of imagination into something tangible

- Stigmas around taxidermists vs current practice e.g. recycled materials ethically sourced, the banality of evil

- Taxidermy isn’t an intrinsically immoral practice, for example in the cases of deceased pets, ‘taxidermy for the grieving’ or ethical sourcing through roadkill, but it does suffer the connotations with its origins. (Stuffed, 2019)

- A skilled taxidermist might theoretically reimagine a deceased London fox, scarred with road rash, lifeless on a pavement in any position, even in a natural stalking manoeuvre, then it can be used in an art piece, or even taken to schools to educate students. Encouraging this kind of publically accessible ethical taxidermy is actually an opportunity in today’s world, rather than a cruelty or a lack of respect for the dead and although there are outliers who still use blood sports to source their private collections, this is more an issue of the individual rather than the craft. Many creatures, exotic and native, are preserved with natural or insignificant causes of death, the most historically popular example of this is in the death of a pet, or the resident of a zoo.

- Utilitarian and Speciesist Peter Singer states that “in suffering, the animals are our equals”

- Amateur exotica (houseplant colonialism)

- The problem of audiences – those willing to enter a room or buy a ticket have already fulfilled a level of completion in terms of thought process – i.e. a person who goes to see an exhibit on the effect of plastic pollution on animals isn’t going to be spending the rest of their time ramming straws into turtles are they?

- The proposition of a ‘Museum of Natural Art’ is one that could be a brilliant opportunity to praise not only exotic and curious objects rooted in nature, but also that which we overlook on a daily basis - a nature positive exhibition. Despite installations in modern art galleries worldwide, there ceases to be a consistent venue, in contrast to more established institutions (e.g. if you want portraiture you go to the portrait gallery, natural history, the NHM etc.). There are plenty of works being conceived, and even the thousands of unused taxidermy specimens in existing museums could serve to benefit a natural art institution.

It is often suggested in the modern world that we need a ‘reset’, however, one could propose that creating institutions for the new generation who are being held responsible for the correction of cumulative world destruction by their predecessors is a necessary step for actual change. A good example of this would be the topography of terrors, situated in Berlin, which details Germany’s role in world war 2 with admirable self-critique; or similarly artist Darren Cullen’s Museum of Neo-Liberalism in London which satirises and informs the public on the problems of the modern world (viewable here: https://www.spellingmistakescostlives.com/museumofneoliberalism).

An institution using the natural world to its fullest potential would be an active way to make sure that the society we exist in can actually progress with knowledge, rather than just perpetuating the issues prescribed by our current system. It’s far too easy for the impressionable to scroll past a social media post about feminism or the climate crisis and be coaxed in by the flashy redtop opinions of denial and hate – and this isn’t an issue that will be eliminated by the mortality of previous generations; instead we need to make functional decisions to enlighten the populous rather than leave those born into stagnation in a feedback loop. it may be hard to kick against the pricks, but if humanity claims, as it often does, to be of a higher order than animals, it should be easy to create a system in which we actually learn from the things around us. Taxidermy was evidently started in order to create and share stories, albeit from a place of vanity, but this anthropocentric craft now can act as a way to benefit our world, without being so abstract or exclusive as to alienate those excluded from the ‘art’ sphere. It isn’t leftist modern art, or traditional old masters, it (when done well) is as new as it is old. frozen in a state of almost permanence, and by heralding it and repurposing it, we could defrost ourselves from the ice age of anti-naturalism we now find ourselves in.

- Although we now have David Attenborough and 4k ultra HD, we still need to see things first hand, evident from Akeley’s experiences with the mountain gorilla (Akeley, whilst on an expedition looked into the eyes of a Gorilla and had a classic movie moment, hung up his rifle and went on to help the creation of the national park that serves to protect the critically endangered animal)

- public interest (let alone intelligence) has greatly waned in modernity, while ignorance of this fact has only increased (Dunning-Kruger),

- importance of having institutions compensating the lack of educational opportunities is fundamental in the working class (especially when the exposure is lessened by those in power)

- Conclusive remarks on Akeley’s importance in seeing Taxidermy as an art form and how his reinventions should encourage our own. (end of essay should question if ‘art’ is intrinsically inanimate/ non-organic, or if when so much art is inspired by the living world, why taxidermy is still sparsely used– what defines that which is art and what is disposable?)

0 notes

Text

Akeley Synopsis

(Fig1: Unknown Photographer, Taxidermist Carl Akeley posing with the leopard he killed with his bare hands after it attacked him, 1896 [Photo])

‘Mounted animals were already obsolete as a viable form of zoology when the Natural History Museum (London) opened — researchers behind the scenes were increasingly focusing on the living animal, as stilled, frozen bodies continued to educate the public. It was precisely because taxidermy had become the bankrupt estate of scientific research that these objects entered the field of artistic reflection.’ (Lange-Berndt, P., 2014)

Taxidermist Carl Akeley was born in rural Clarendon, New York state, in 1864. Growing up in the Gilded Age and surrounded by a culture of outdoor sports like hunting, Akeley would become known for applying his artistic abilities and obsession for realism to revolutionise the practice of taxidermy. In contrast to the longstanding status quo ‘upholstery’ of an animal (usually a skin stuffed with inexpensive materials), Akeley earned his title as the ‘Godfather of modern taxidermy’ by being the pioneer behind meticulously sculpting the structure of an animal in modelling materials, then mounting the skin onto the cast, giving the animal an uncanny resemblance to its extant form.

This project will look at his work as a form of art, and less at the person he was or became; however, it is important to consider the suffering he was responsible for; that although he established a painstakingly accurate way to depict natural evidence as art, he was also a product of his times – a museum salaried hunter responsible for the availabilityof ‘voucher specimens’ (a specimen that serves as a verifiable and permanent record of wildlife by preserving as much of its physical remains as possible). Already vulnerable - and therefore valuable - animals were collected on excursions funded by institutions, although one could argue that Akeley and his colleague/ wife Delia (along with their cohort of assistants, artists, photographers and writers) were the best to employ, for their eccentricity and craftsmanship allowed them to best depict any animal subject to this practice, making something appear so convincingly real that no-one would think one was involved at all.

Akeley, C & Akeley, D, Fighting Bulls,1905 [Taxidermy] Field Museum of Natural History.

Akeley not only worked during the time when photography and film was being used (albeit in a novel capacity) he also helped to pioneer this craft whilst still working for museums.In the modern world, the majority have easy access to photographic appliances, and with dedicated channels to view documentaries on it is easy to dismiss taxidermy as an antiquated craft, although one should consider that without the concept behind preservation, there would have been no motivation to create the motion picture camera used to film the first documentary ‘Nanook of the North’ in 1922.The idea of capturing the wild was held in higher regard than the blood - sport of hunting to Akeley, and in later life, according to Alvey (2007), he retrospectively indicated that:

"the camera hunters appeal to me as being so much more useful than the gun hunters." The latter had amassed a great deal of knowledge about the wildlife of Africa, but left no record of it, while the "camera hunters" have left a photographic record - "and when their game is over the animals are still alive to play another day."

Alvey, primarily looking at the photographic and filmic legacy of Akeley, continues and comes to highlight a key component of his character noticeable in many, if not all ‘great artists’: the obsessive drive to ‘capture’ the natural in a mimetic form; applying “André Bazin's proposition that at the root of the representational arts is an "obsession with realism" or in his famous shorthand, a "mummy complex.". This is a central factor whichmakes Akeley suitable for the discussion of taxidermy as an ‘art’. As the figurehead of modern preservation, he transformed what was primarily a practice following the rules of fast fashion into a creative craft, and instead of anthropocentric pride, the depiction of reality was key. In pairing his technical mind with a desire to capture an ‘as in life’ version of what he witnessed in the biological world, he became the de facto natural curator, his fame perpetuated by his mania.

retrospective on taxidermy

Historically, taxidermy has always had a quintessential essence of egocentricity. One could say that the act of animal preservation has fallen somewhat into the same category as murder, where an individual has the power of a god; whether taking a life, or curating death’s trophies. At the same time, taxidermy has also always been something to visually fascinate, the key to any form of art, which is why taxidermy was popular for wealthy collectors as something that they could contextualise out of self-interest rather than facts (a practice commonly seen in western religious art).

Fig.XXX: Anonymous, for Ferrante Imperato (1599) Dell’Historia Naturale[Engraving]

The Wunderkammer (or ‘cabinets of curiosities’) of the 1400s onwards formed the basis of what we now know as the ‘museum’. Facilitated by colonialism, the upper classes could entertain guests with tales of obscure objects and fantastic beasts, oftentimes bolstered by false self-insertions, within dedicated spaces and even whole rooms, as depicted in fig. XXX. (Aloi, 2021). Even today one can see hunting trophy rooms in films and programmes as an extension of this practice, but Aloi suggests that generally speaking:

…during the 18th century the focus shifted. The rise of science as a defined discipline meant that collections could no longer just represent the wealth and intelligence of the owner, but that they needed to make sense of the world we lived in a more objective way. This is what the human skull we see on the top shelf of [Domenico] Remps’s cabinet anticipates—an existentialist urge to understand life and the knowledge that despite the wealth one might accrue, death will at once take it all away. (Aloi, 2021)

Thus, personal endeavours and collections of favoured objects; hunted, stolen and bought were purchased by institutions, then curated for the public. The nature of these cabinet collections meant that the line between the artistic and scientific would overlap greatly, false preservations and genuine artefacts housed together would be compartmentalised. Just as art galleries specialise their interests to say, portraits or modern art; nature, science and art were sorted via institution. Due to the components of taxidermy being largely animal matter, they would have been classed as scientific, or indeed just kept for ‘scientific study’; as preservations of nature, they were kept with seashells and archaeological bone fragments in the drawer marked ‘world science’.

Preserved animals have always been popular attractions and opportunities to make a spectacle of humanities’ ‘others’ – but this schism between human and non has been exacerbated by time and modern life, our individualism removing us from a system we are biologically grafted to. To amputate taxidermy from the context of visual culture completely is like taking the skull out of Remp’s cabinet, it eliminates the potential energy by imposing exclusivity. Although one could say that museums allow free access to a resource, they also falsely preserve the concepts of the pieces they house. Akeley himself evidently thought it best that the specimens he would deliver for institutions like the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago would provide the public with ‘as in life’ depictions of animals and their habitats, potentially recognising the importance of context within his craft (or arguably the product of his mania for detailing the tangible animal), which lead to many institutions following suit, producing inspiring displays from the addition of context counteracting the anthropocentric collector atmosphere of museum menageries.

Howard, E., Photo of ‘Muskrat Group’ (1890) by Carl Akeley, (No Date) [Photo]

Akeley’s craft, for example,Fig.XXX, raises the argument of whether a faithful depiction is less ‘artistic’ in preservation, but it could be contended that, in fact, to meticulously consider every detail of all the subjects within a recreation is as much an artistic endeavour as a scientific one. Take for example, how the anatomical depictions of the human body existed as art after the ancient Greek Galen’s works (who had only dissected other animals), until Andreas Vesalius’ illustrated book disproved theories held for over a century. Art and science exist with a similar symbiosis as humans and nature, to undercut one side would be damaging the other, when in combination truly amazing things can be created: in Akeley’s dioramas, there is biotic artistry as well as artistic science

0 notes

Text

Draft submission Abstract/ Blurb

Using the life and work of radical taxidermist Carl Akeley (1864-1926) as a point of entry, this project aims to query the artistic merit of animal preservation and its future in the modern artistic lexicon.

As opposed to stagnating as a remnant of history, the act of taxidermy is still executed by a growing number of hobbyists and interested parties alike, however the housing and public display of preserved animals has waned, leaving fixed instalments such as those in the Natural History Museum gathering dust, slowly degrading.

Spare the few focussed exhibitions used to educate tourists, taxidermy is seldom seen in an artistic sense. Akeley’s work, which is in great part responsible for progressing animal preservation away from being an anthropocentric ‘furniture’ craft and towards a narrative and didactic production, allows us to scrutinize taxidermy practices as not exclusively based in pride, rather, as a viable artistic form and material – a claim supported by the works of Claire Morgan and Iris Schieferstein.

0 notes

Text

Museum trips primary research

Hornimans museum

In the past month, I have visited the Hornimans Museum in South London twice: the first being an opportunity to find some inspiration for this project, and the second was to do location drawing. We were instructed to do this at the British museum, but when the options are between ‘colonialism for the whole family’ and drawing animals in real life without them moving, there is a clear winner (although in thinking too much about it you realise that you’re using grotesque reference images, and that for a good 200 years, most artists were starting out by doing the same thing). This factor would probably form a good discussion point for the project, in that the Hornimans is more of an art gallery than a museum. These are items chosen by the family (whose wealth and status allowed them to attain these items stemming from the tea trade, yet another colonial practice ‘subtly touched upon’ in the far most corner of the museum) on the basis of their aesthetic interest. A good example would be the Japanese decorated dolphin skull, which sits in a cabinet in their world history section.

However, the taxidermy housed in the museum follows the basic standards of artistic depiction, as well as scientific organisation. Badgers, foxes and ostriches presented as if we were in the wild with them, albeit with lifeless, beady glass eyes jammed in, some visible stitching and occasionally a more art than science approach being the most apparent signs that they fall in the realm of ex-living. This presentation is owed at least in part to Carl Akeley, who revolutionised the presentation of the preservation, in contrast to the ‘guestimation’ practices, rogue taxidermy and the glutton syndrome of taxidermy (see 50 exotic birds in a cage, or the false merman housed beneath the dolphin skull).

A large majority of the animal exhibits in the main room are presented as educational, separated out by taxonomic classifications or animal characteristics, but it has to be acknowledged that this museum was once a huge wunderkammer (a way to show off at dinner parties) – although they should be commended for the repurposing of empire mentality as education. Another aspect that became apparent through viewing the collection was that taxidermy is an art form which requires the craftsman to do so much, that there should be no sign that they were there at all. The artistic merit in taxidermy could be argued as being in the essence of nature, rather than in creating something wholly new.

But this does raise issues, such as art acting as a justification for suffering, which applies hugely to the practice of hunting for mounts. It is admittedly a great way to learn the forms of animals by using someone’s craftsmanship to convey the essence of an animal, but only in ethical taxidermy could this be justification enough (the animal died regardless of human interaction, or was unintentionally killed, but it’s pelt will be immortalised for education).

NHM and behind the scenes exhibition

British institutions have a wonderful way of playing god through committing acts of mindless violence and expecting a literal or metaphorical medal.

We are consider ourselves top of the food chain, particularly when attempting to prove an invalid argument; animals most likely do not think of classification as a high priority while completing the birth-survival-death routine. As a species, we try to distance ourselves from the fact that we are animals by saying things that seemingly qualify us as higher, or more than an animal. In taxidermy as art however, we end up quite surreally using an animal’s death to prove we are more than animals, through the method of killing - an animalistic act (although taxidermy was traditionally bloodsport, or death for sadistic joy and bragging rights rather than survival, so we acted more like dolphins or other predatory animals). As humans, we tend to slip quickly into the ‘collect them all’ mentality and we have synthesised a way to stop most occasions when something could best us.

In taxidermy, the product outlives the name of the hunter: we look at taxidermy to see the animal, in the same way that there are truly wonderful works of art independent of our knowledge of an artist. Science requires empiricism, facts and figures, names and dates, whereas art only needs to evoke something within a person to be considered art, so taxidermy is an informed version of art, stuck between states of existence.

The education provided by the taxidermy in the NHM is minimal really, especially compared to the Hornimans or the Grants Museum – which is a problem. This leads to these creatures being separate from the ‘human world’ as they aren’t contextualised with what visitors know. The greatest book ever written is just words put in order, but the craftsmanship is what makes it the superlative. This isn’t to say that we scrap the lot and just make everything into a dioramic depiction of reality, but rather that we make more of an effort to educate, rather than remember. The mass extermination of American bison was something that was instigated by white colonialists, but only when taxidermy bison were taken to Washington did (white) people actually start to care. One component of the problem is that a lot of the creatures in the NHM are immortalised as singularities rather than as narratives, as a blip on the radar with no traction. We are remarkably selfish mammals (the fault of which is both genetic and contextual), wanting things to matter to us whilst suffering from a relatively small ability to rationalise amounts (e.g. 20,000 people or 600 rhinos). To see an animal is one thing, but to be able to see the life additional to the skin strenuously placed on a mount, is something with a lasting effect. This would lend itself not only to the theory that taxidermy should be viewed with the same eyes cast towards art conveying a narrative, but also to the argument that recognising and exploiting taxidermy as an art form forces humans to actually care about the natural world, and why avoiding the gruesome root of our evolution is easy when institutions make it easy (acknowledging that humans are perfectly capable of this without help) – without a challenge, we are not the apex predator of the natural world, rather, we are lower than any animal on earth.

The ‘Behind the Scenes’ exhibit in the Natural History Museum allows paying members of the public to go into the scientific belly of the whale, where scientists attempt to decipher the codes of life with DNA swimming around in now reddening and yellowing specimen jars. The guide takes you through vacuum sealed air and temperature-controlled rooms, explaining the pay per view specimens. Only when you get to the main specimen room does it hit you (not just the smell of decay and preservative fluids): the attempt to document everything this side of the last ice age; mammals, birds, reptiles, fish, amphibians and invertebrates of all sizes and origins, and lying in the room a giant squid called Archie - shadowing Darwin’s specimens. Collected on his trip to the Galapagos, these are marked with yellow dots on the top of the jars, signifying that they are the frame of reference for a hitherto unknown species, the OG, the original genus. On the wall, there is a list of pager extensions to each of the head scientists, for each area of the animal kingdom – this part of the institution cares for these specimens so more can be learned from the animals which make up the earth, and where despite our efforts, humans lie. This experience (although obviously marred by the fact that the man guiding the tour is paid by the museum) did allow me to rationalise wet specimens as scientifically important, as well as being another visual display of human dominance. This isn’t to say they aren’t artistically important, but that their scientific contributions will always outweigh their creative ones.

Notes:

Taxidermy isn’t an intrinsically immoral practice, for example in the cases of deceased pets, ‘taxidermy for the grieving’ or ethical sourcing through roadkill.

Avenue of discussion of where art and desecration meet – we obviously play god to any living creature beneath our rung and art has always had a tumultuous relationship with religions (example; the forbidden depiction of the prophet in the Islamic faith, or Christianity’s art as thought control). One of the essential components of art is sacrilege, to create something as if we were gods – but does taxidermy exist, if separated from all factors, as a purer form of art – a great artist steals and all that. so, is there justification for taxidermy and preservation as an artistic outcome in the separation of art from artist, art from owner and art from materials?

Shellac is made from crushing lac bugs, and artistic materials still contain it, but is the theory that a bug is lower than an ‘animal’, and that taxidermy presents an ‘as in life’ version reason enough that we take more issue with one or the other?

Stigmatization around taxidermists?

Question for Marion:

How do we reference an uncredited or unknown photograph (or if it is of such an age the information isn’t available beyond the host source)?

0 notes

Text

Research Project further widening

Research project ideas:

Taxonomy/ Taxidermy

Colonial practice now used for retrospective study – progress through past suffering

Amateur exoticism – houseplant colonialism

‘Freak shows’/ human obsession with the other or death (Diane Arbus/ Joel Peter Witkin, vs the real experience)

Ethics and speciesism

Immortalisation of extinct animals – seems like a weak consolation prize

Peter singer: giving preference to our species over another, in the absence of morally relevant differences

There was a time when the majority of people thought it was normal and right for members of one group to literally own members of another group – based on a morally irrelevant difference, that of skin colour. (Animals as lesser due to their evolutionary rung/ relative intelligence)

How we treat animals relative to our history of slavery

Jeremy Bentham: the question is not, ‘can they reason?’ Not ‘can they talk?’, but rather, ‘can they suffer?’.

Less interested in the animal ethic argument, more so in our view towards suffering.

We have artifacts and things to look at ultimately through death (e.g., statues, stolen artifacts, basically the entirety of museums are built on death.)

Ferry Van Tongeren/ Jaap Sinke: importance of the 17th Century plates and the expressions/ stories a taxidermied animal can tell

Taxidermy hasn’t yet become ‘questionable’/ scrutinised in the same way that other empire practices are – there hasn’t been a great effort to hide it in the same way that the slave trade has (relative to the animal value argument?)

How far can you push the argument of ‘scientific purposes’? (Concentration camps, ownership of people, etc)

Vanderbilt collection (the rich white man problem)

Modern taxidermy vs OG taxidermy?

Carl Akeley: killed a leopard with his bare hands, considered one of the fathers of modern taxidermy/ accredited with the accurate taxidermy + diorama formula, hunting buddies with Teddy Roosevelt, whilst hunting mountain gorillas had a moment of introspection quit hunting and convinced the king of Belgium to start the first national park in Africa.

When travelling, Akeley would take animal and landscape artists to countries in the 1800’s with a cohort of aids and scientists (and quote ‘native porters’) to accurately depict an animal; could be argued as homage, but he still shot the animals in the face so isn’t exactly black and white.

Oversaturation in Taxidermy?

‘Road Rash’

Rogue taxidermy

‘Hunting as conservation’ hmm

Male dominated field in terms of recognition and perceived practice, despite the active presence of female taxidermists (could be an alleyway to the patriarchal ownership brain)

Witch doctors, freak shows, taxidermy – a level of spectacle

White people using any excuse/ justification for the extension of colonial mindsets

The basis of our ‘enlightenment’ as a species relies of suffering

Potential questions:

Can we justify that which is rooted in BLANK as artistic in modernity?

What does taxidermy tell us about our cultural stance on Empire?

The human obsession with exoticism and symbolic ownership (manifestations of wealth)

How can taxidermy help us scrutinize our own actions/ views/ etc?

Are the products of death or suffering an art movement? (Wet specimens, graveyards etc.)

Is taxidermy the most human of colonial practices still practiced?

What can taxidermy tell us of how our relationship with death or suffering has impacted our philosophical/ ethical outlook towards art.

What can taxidermy tell us about our philosophical/ ethical outlook on life and death within or as art?

What can taxidermy tell us about our relationship with ‘death’ and how it is expressed in art.

Sol Lewitt on conceptual art: the idea behind the concept is more important than the outcome – lewitt would have made diarams and instructions so that any artist or group of artists could execute them –

The concept of art is more important than the physical outcome: built lego is art, Graffitti is art, taxidermy is art - - using the term art as security to action

Not only the death of an animal Taxidermy and the death of artistic mysticism (Durer and rousseau find earlier less accurate examples)

Animals considered as artistic works from the hands of god (how we became the God)

Denial of death by ‘immortalisation’, a normalisation of immortality through ‘art’

Denial of extinction because a physical copy of the animal still exists

How much can suffering be justified in the name of science/ art or religion?

(suffering has often been excused by means of scientific purposes, or indeed artistic, patriotic or religious ones)

Issue of ethics vs engagement

It’s never been enough for humans to see an other, they have to own it in some degree.

Humans stranglehold over earth, the biological and cultural (white people) capitalist mentality

The normalisation of non naturally occurring animal suffering lead to it becoming an art form

The human animal

Art as a means to acknowledge death has been corrupted by things like taxidermy as it highlights the mortality of ‘other’ rather than ourselves/

Primary research opportunities:

Behind the scenes at the Natural History Museum (attended in September)

Grant Museum of zoology (UCL)

Horniman’s Museum

Highgate Cemetery

Absurdism

The efforts of humanity to discern meaning or ultimate truth in the universe ultimately fail because no such thing, at least to humans exist.

This does not mean that life is meaningless, rather that we are free from the governance of a random generator universe.

- Relation to our algorithmic existence?

- Our worlds hyper fixation on freedom and emblems of such have become our ‘gods’.

‘That which is, cannot be true.’ – Herbert Marcuse. (Our perceived existence is preapproved, controlled, and prescribed)

The Precariat (continued/ refined from second year)

‘The road to happiness lies in an organised diminution of work’ – Bertrand Russell

VERY HARD TO BRING TO A FOCUS

Post Punk as an artistic movement

Taxidermy

Wet specimens as more scientifically required, taxidermy as a display (reasoned either as scientific, educatory or artistic), but by extension a symbol of our history

Taxidermy as education to artists before widespread photography

The spectacle of the obscure, the spectacle of the other

Art vs science

The conservation argument

Animals or figures that hold a personal relevance or meaning are taxidermied more often in modern society, rather than taxidermy being the basis of a fabricated or real meaning (eg taxidermied tigers bought at a market owned by a man using them for social elevation)

Rogue taxidermy

The separation of our animal selves and the anylitical ‘human’

We are desensitized to the reasoning behind museum taxidermy – we no longer see great beasts; their prowess is only fully appreciated by those unequipt with modern technology.

https://mdx.kanopy.com/video/stuffed

cabinet of curiousities/ wunderkammer:

a wide variety of objects and or artifacts with a tendency of being extraordinary, rare, taboo or opulent etc. these were originally used by aristocrats to essentially compact a museum into a room to show off at parties.

Sotheby’s page article:

Curiosity cabinets served to entertain guests at the aristocracies parties and gatherings.

An ostentatious display

Used primarily for the basis of fabricated stories built to impress those in attendance

‘Like everyone else, the wealthy liked to define their personalities through the possession of glamorous objects as tangible tokens of their intelligence, erudition, wealth, and taste. They had already understood that precious objects held power over people and that associations between luxury items and personality engraved long-lasting impressions. But in all honesty, the cabinets weren’t always built on truth—artifacts and preserved animals and plants were sometimes purchased at the markets in Florence and Rome rather than collected directly by the owner of the cabinet. Some, like the famous mermaids made by stitching together the torso of a monkey to the tail of a fish were wholly fantastical fabrications closer to art than natural evidence.’, going on to say;

‘But all in all, that didn't really matter. In spirit, the cabinets were not meant to be scientific—they were a place of the imagination in which those who could afford to do so, constructed their own personal versions of the world. Standing at the center of this mini-universe and pointing at the objects to disclose their deepest secrets, collectors felt a sense of ease and mastery over a world that most often appeared too big, too confusing, and too inhospitable. ’

Personal collectons forming the foundation of the modern museums.

Cabinets had no real scientific or formulaic order

‘during the 18th century the focus shifted. The rise of science as a defined discipline meant that collections could no longer just represent the wealth and intelligence of the owner, but that they needed to make sense of the world we lived in a more objective way. This is what the human skull we see on the top shelf of Remps’s cabinet anticipates—an existentialist urge to understand life and the knowledge that despite the wealth one might accrue, death will at once take it all away.’

‘Knowledge was not yet compartmentalized in separate subjects, as it is today, and the distinction between art objects and natural objects was also very fluid ’