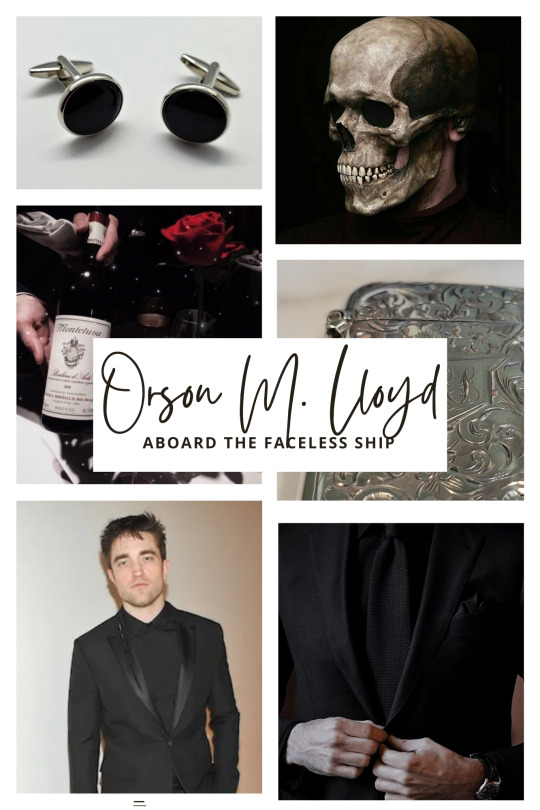

#✘ orson lloyd | aesthetic

Text

LAWLESS EVENT 002 — the faceless ship.

#✘ orson lloyd | aesthetic#✘ orson lloyd | visage#✘ orson lloyd | event 002#lawlessevent002#taking bets on whether or not orson crafted that mask himself

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sci-Fi Saturday: Five

Week 29:

Film(s): Five (Dir. Arch Oboler, 1951, USA)

Viewing Format: Streaming Video (Amazon)

Date Watched: 2022-02-11

Rationale for Inclusion:

Late in the runtime of last week's film, The Thing From Another World (Dir. Christian Nyby, 1951, USA), as part of a monologue trying to convince his fellow occupants of the Arctic base not to destroy the carnivorous plant alien that has already drained the blood of multiple scientists and sled dogs, Dr. Carrington (Robert Cornthwaite) concludes his plea for the importance of the pursuit of knowledge at all costs with, "We split the atom." At which point, one of the airmen, Lt. Eddie Dykes (James Young), cuts in with, "Yes, and that sure made the world happy, didn't it?" The sardonic quip stops Carrington cold.

In 1951, only six years had passed since the United States had deployed atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in August of 1945. Whilst news of the destruction and atrocities were initially slow to spread, by the time the film takes place the scientists and airmen in The Thing no doubt knew the horrors inflicted upon Japan. Furthermore, the Soviet Union had detonated its first nuclear weapon in 1949, and the Cold War was very much underway.

With this cultural context in place, it follows that the post-apocalyptic film would make a comeback in the 1950s. Rocketship X-M (Dir. Kurt Neumann, 1950, USA) featured a post nuclear disaster society on Mars, but this survey has not featured a film where the central narrative is built around people trying to survive in a post-apocalyptic world since natural disaster film Deluge (Dir. Felix E. Feist, 1933, USA). So when I encountered Five (Dir. Arch Oboler, 1951, USA) described as the "first to depict the aftermath of an Earthly atomic bomb catastrophe" whilst perusing Wikipedia's science fiction cinema list, I knew it was an essential film to view.

Five was an independent film written, directed and produced by Arch Oboler, a successful radio dramatist who followed in Orson Welles' footsteps in transitioning to filmmaking. Oboler had directed three films prior to Five, and to keep costs down on the production the cast featured relatively unknown working actors, the crew was recruited from recent University of Southern California graduates, and the primary filming location was a Frank Lloyd Wright designed guest house on Oboler's Malibu ranch.

Reactions:

With its limited cast and locations, Five is dominantly the kind of no frills character study that would become more commonplace during the 1960s. It is simply and competently made with aesthetics that may remind modern day audiences of episodes of anthology television series, like The Twilight Zone or The Outer Limits.

As implied by the title of the film, the small cast of characters includes five people: the pregnant Roseanne Rogers (Susan Douglas Rubeš), white everyman Michael Rogin (William Phipps), the aged bank clerk Oliver P. Barnstaple (Earl Lee), black everyman Charles (Charles Lampkin), and supposedly affluent adventurer Eric (James Anderson). Roseanne's sex and Charles' race become sources of drama, mostly because Eric exhibits a behavior described decades later by sociologists as "elite panic."

Lee Clarke and Caron Chess of Rutgers University coined the term in a 2008 journal article, in which based on available research and case studies of disasters from the 1950s through 2001 they determined that the source of panic in these scenarios was not the general public devolving into a mob, but by elites, fearing that their power and wealth would be violently stripped from them by a mob. Clarke and Chess specifically identify three relationships with panic that occur during disasters: elites fearing panic, elites causing panic, and elites panicking. My introduction to this concept came via an episode of the podcast Behind the Bastards recorded during November of 2020, when amid the COVID-19 pandemic and stress around the presidential election having a reminder that the majority of people are inherently giving, caring, communal creatures was a huge comfort.

In Five, after an initially violent encounter, Michael and Roseanne band together for survival, with Oliver and Charles later joining them. They compassionately deal with Roseanne's pregnancy and Oliver's mental dissociation and decline from radiation sickness amid their limited resources. Oliver's dying request to visit the nearby ocean results in the old man having as peaceful a death as available under the circumstances, and the discovery of a man washed ashore, Eric.

The injured Eric's explanation for how he survived the atomic bombing is bizarre compared to the banality of the others' explanations, who were shielded from the blast via being in an elevator, lead-lined hospital x-ray room, and bank vault, respectively. Instead Eric was actively climbing Mount Everest alone when a blizzard stranded him. When he made it back to basecamp he found other climbers dead. On foot and via abandoned conveyances Eric had made his way back to America, encountering no other survivors along the way, just dead bodies.

Eric's journey in its entirety sounds highly unlikely, but at first only one aspect utterly defied my credulity: who climbs Mount Everest alone? Mountaineering is not a pet topic of research for me, but I know enough to know that no serious climber attempts Everest without guides, frequently members of the local Sherpa community. "What happened to his sherpa?" I demanded aloud when we got to this point in the film. "Did he eat them?"

Given that Eric is gradually revealed to be a greedy opportunist, in retrospect his story may have been nothing but lies. It seems more likely he was in the United States the entire time and leapfrogged from one pocket of resources and survivors to another until he ended up washing up on the beach. Regardless of whether he actually was a billionaire or not--and the film does nothing to disprove his account--he nevertheless has an elite mentality: trying to hoard resources (including Roseanne) to himself.

Eric is the sociopathic evolution of the wandering rapists from Deluge, and ultimately serves the narrative role of Michael's doppelganger. Michael may have initially tried to sexually assault Roseanne, but spends the rest of the film making up for that feral moment. Eric is predatory and ends up becoming a murderer in the course of the narrative; after being banished by the others, he goes back to steal supplies and kills Charles when he is caught. Michael is spared having to also become a murderer by the reveal near the end of the film that Eric has radiation poisoning and likely does not have much time left. The film makes it clear that Michael is a good man, and deserving of being the new Adam of the post-apocalyptic world.

Roseanne earns her new Eve status in part by being the token female, and in part because she is devoted to her missing husband until she finds definitive proof that he died in the bombing. Her dedication to her husband and baby are all that is needed to qualify her as a good woman.

Unfortunately, her newborn dies for reasons of narrative convenience. Apparently it was too much to ask for Michael to be father to a baby he did not conceive. Instead it ends with Michael and Roseanne left alone. Despite the tragedies and threat of radiation sickness lingering, Five closes conservatively and reasonably optimistically: life will go on.

Before I wrap up, I would be remiss if I did not spend more time discussing Charles. His presence is itself a progressive act, given how the casts of most mainstream films surveyed thus far have been all or mostly white. However, he is introduced in a subservient role to an old white man, and spends the remainder of his time in the narrative as a litmus test to show who is the superior white man to repopulate the world: Michael or Eric. The notion that Charles might be a candidate for Roseanne's mate is never so much as suggested. For all the indignities Charles suffers throughout Five, he at least is spared the trope frequently placed on black men of being the first to die. Overall, Charles is a minor step forward for black representation in science fiction cinema.

Five, on the other hand, is a solid first representation of the post-nuclear apocalypse narrative. Later films built on the premise, like On the Beach (Dir. Stanley Kramer, 1959) and The World, the Flesh and the Devil (Dir. Ranald MacDougall, 1959), would result in better movies, but Five deserves greater attention within the sub-genre.

3 notes

·

View notes