#4th pic. backwards cap. says it all

Text

head empty no thoughts just han jisung

#dash is dead now’s my time to post random pics of hanji that are near and dear to my heart#FIRST PIC!!! HIS HEART SHAPED SMILE#the second one with the hood up ok cool guy i see you#third pic THEEE LOML#4th pic. backwards cap. says it all#hanposting

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

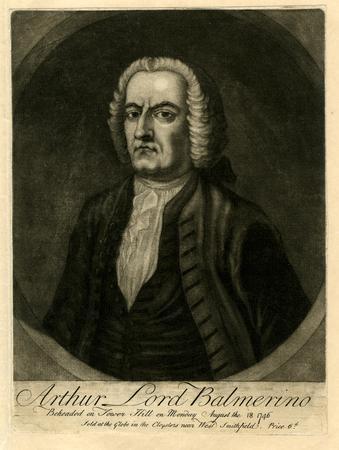

On August 18th 1746 Arthur Elphinstone, Lord Balmerino and William Boyd, 4th Earl of Kilmarnock the Jacobite nobles, were executed.

The two were found guilty of treason and sentenced to death; this was commuted to beheading, rather than the usual sentence of Hung,drawn and quartered, which had already been carried out on some Jacobites, most notably the English Jacobite Francis Towneley on 30th July that year, with eight of his comrades from the Manchester Regiment.

Before I start on this post proper I have to say we should remember that whilst the high profile executions may make the “headlines” in my posts, we should remember the ordinary soldiers that also died, both during the uprising and afterwards. Also the provisions that followed stripping the country of their way of life.

Magnus Magnusson recounts in Scotland The Story of Nation: “Of the total of 3471 Jacobite prisoners, 120 were executed: most by hanging, drawing and quartering, four by beheading because they were peers of the realm -- the privilege of rank. Of the remainder, more than six hundred died in prison; 936 were transported to the West Indies to be sold as slaves [which, at that time, meant that they would almost certainly be dead of yellow fever or the like within two years], 121 were banished ‘outside our Dominions’; and 1287 were released or exchanged”

Of those released my guess is that a large number of these would have been co-opted into the British army. Highlanders were among the world’s best natural soldiers and if given discipline, training and leadership would make a formidable force. Which indeed was proved true.

Numerous clan chiefs were attainted, having their titles and lands stripped of them. More importantly the Heritable Jurisdictions Act of 1746 removed all judicial powers from the chiefs, smashing the very structure of Highland society as sheriffdoms reverted to the Crown. The Act of Proscription of 1746 banned anyone north of the Highland line from the carrying of arms and the Dress Act section banned anyone in Scotland from wearing Highland dress, especially the kilt, on pain of six months in jail – transportation was the punishment for a second offence. Also banned by extensions of the Act were the bagpipes and the speaking of Gaelic in public. In a few short years, that Act had great effect, and the repression of the Gael was almost total. Many Highlanders opted to emigrate to America and Canada in a bid to preserve their way of life that was now under assault on all sides – lowland Scottish people, it has to be said, largely backed the brutal repression of their fellow Scots.

On to the day of the executions, much of this is first hand accounts from the history books.

Everyone who was anyone wanted to be at the execution, among the spectators was the English army officer and naturalist George Montagu, it is his description that I have pinched for an eye witness account of the gruesome events that day in 1746. Montagu was allowed close access to the prisoners from before their trial until they met their end.

“Just before they came out of the Tower, Lord Balmerino drank a bumper to King James’s health. As the clock struck ten they came forth on foot, Lord Kilmarnock all in black, his hair unpowdered in a bag, supported by Forster, the great Presbyterian, and by Mr. Home, a young clergyman, his friend. Lord Balmerino followed, alone, in a blue coat turned up with red, his rebellious regimentals, a flannel waistcoat, and his shroud beneath; their hearses following.

They were conducted to a house near the scaffold; the room forwards had benches for spectators; in the second Lord Kilmarnock was put, and in the third backwards Lord Balmerino; all three chambers hung with black. Here they parted! Balmerino embraced the other, and said,

“My lord, I wish I could suffer for both!” He had scarce left him, before he desired again to see him, and then asked him, “My Lord Kilmarnock, do you know any thing of the resolution taken in our army, the day before the battle of Culloden, to put the English prisoners to death?”

He replied, “My lord, I was not present; but since I came hither, I have had all the reason in the world to believe that there was such order taken; and I hear the Duke has the pocketbook with the order.”

Balmerino answered, “It was a lie raised to excuse their barbarity to us.” –Take notice, that the Duke’s charging this on Lord Kilmarnock (certainly on misinformation) decided this unhappy man’s fate! The most now pretended is, that it would have come to Lord Kilmarnock’s turn to have given the word for the slaughter, as lieutenant-general, with the patent for which he was immediately drawn into the rebellion, after having been staggered by his wife, her mother, his own poverty, and the defeat of Cope.

I’ll interject here this conversation pertained to the lie that the Jacobite commanders issued an order that “no quarter” was to be give ‘no quarter’ meant that no prisoners would be taken. Any men on the battlefield would have no mercy shown to them and surrender would not be accepted.”

On the eve of the Battle of Culloden the Duke of Cumberland was determined to end the Jacobite Rising and prevent the Jacobites from ever being capable of challenging the throne again. After losing to the Jacobites at every turn, up to this point, he would not let them win again. To motivate his men he informed them that Lord George Murray had ordered ‘no quarter’ to be given to the Government men on the field. This meant the men would be shown no mercy by the Jacobites . However, this claim was not true. No such order had been given.

From copies of Lord Murray’s orders there was no mention of ‘no quarter’ anywhere. But, in Cumberland’s papers there was a copy in which the words ‘and to give no quarters to the electors troops on any account whatsoever’ had been inserted. Whilst Cumberland may not have been responsible for doctoring the order he certainly did not shy away from the words written and retaliated in kind.

After the battle Cumberland ordered his men to search out any surviving rebels who were to be treated as traitors, outside the conventions of international combat. Those with the French Royal Ecossais or the Irish Piquet’s would be regarded as prisoners of war but everyone else was to be considered traitors. Whilst some men in the government army refused to kill, and tried to turn a blind eye, there were some who committed terrible acts. As well as wounded soldiers, civilians, women and children were all killed in the horrible aftermath of Culloden.

Back to Montagu’s account…..

“He (Kilmarnock) remained an hour and a half in the house, and shed tears. At last he came to the scaffold, certainly much terrified, but with a resolution that prevented his behaving in the least meanly or unlike a gentleman. He took no notice of the crowd, only to desire that the baize might be lifted up from the rails, that the mob might see the spectacle.

He stood and prayed some time with Forster, who wept over him, exhorted and encouraged him. He delivered a long speech to the Sheriff, and with a noble manliness stuck to the recantation he had made at his trial; declaring he wished that all who embarked in the same cause might meet the same fate.

He then took off his bag, coat and waistcoat with great composure, and after some trouble put on a napkin-cap, and then several times tried the block; the executioner, who was in white with a white apron, out of tenderness concealing the axe behind himself. At last the Earl knelt down, with a visible unwillingness to depart, and after five minutes dropped his handkerchief, the signal, and his head was cut off at once, only hanging by a bit of skin, and was received in a scarlet cloth by four of the undertaker’s men kneeling, who wrapped it up and put it into the coffin with the body; orders having been given not to expose the heads, as used to be the custom.

The scaffold was immediately new-strewed with saw-dust, the block new-covered, the executioner new-dressed, and a new axe brought. Then came old Balmerino, treading with the air of a general. As soon as he mounted the scaffold, he read the inscription on his coffin, as he did again afterwards: he then surveyed the spectators, who were in amazing numbers, even upon masts of ships in the river; and pulling out his spectacles, read a treasonable speech, which he delivered to the Sheriff, and said, the young Pretender was so sweet a Prince that flesh and blood could not resist following him; and lying down to try the block, he said, “If I had a thousand lives, I would lay them all down here in the same cause.”

He said, if he had not taken the sacrament the day before, he would have knocked down Williamson, the lieutenant of the Tower, for his ill usage of him. He took the axe and felt it, and asked the headsman how many blows he had given Lord Kilmarnock; and gave him three guineas. Two clergymen, who attended him, coming up, he said, “No, gentlemen, I believe you have already done me all the service you can.” Then he went to the corner of the scaffold, and called very loud for the warder, to give him his periwig, which he took off, and put on a nightcap of Scotch plaid, and then pulled off his coat and waistcoat and lay down; but being told he was on the wrong side, vaulted round, and immediately gave the sign by tossing up his arm, as if he were giving the signal for battle. He received three blows, but the first certainly took away all sensation. He was not a quarter of an hour on the scaffold; Lord Kilmarnock above half a one. Balmerino certainly died with the intrepidity of a hero, but with the insensibility of one too.”

Pics show the Lords, the second is a satirical drawing of Lord Balmerino, next is a depiction of the crowd and scaffold on the day. Finally is a plaque at Trinity Square Gardens, Tower Hamlets, London where the executions took place.

13 notes

·

View notes