#And I think the Folio Society can sometimes ship to the US too?

Note

I just stumbled into your beautiful editions and realized, you don't ship to the US?!? *sobbing* Love, love your Terry Pratchett covers.

Ah yes I'm sorry! Some books we can, but it all depends on the rights we managed to acquire. If we don't acquire US and Canadian rights, we legally can't distribute in North America, because those rights belong to someone else.

#Gollancz Blogging#Asks#Rights are a tricksy thing#Subterranean Press in the US do some really stunning special editions however#And I think the Folio Society can sometimes ship to the US too?#Edited to correct my spelling of Canadian#Canadananananian

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

a glass bell

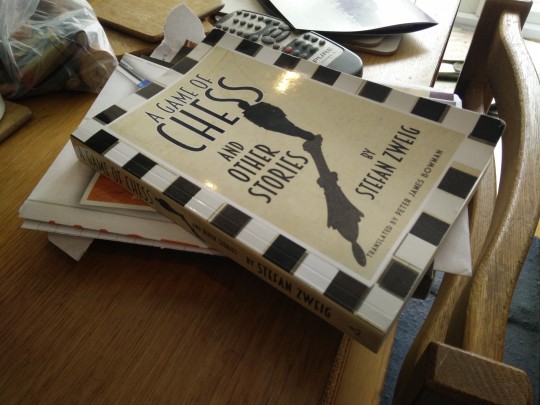

This book is a short collection of stories by Stefan Zweig. There are only four of them collected here. I’ll describe each one in turn.

The Invisible Collection describes a visit to the home of an old blind man by an antiques dealer. The dealer arrives expecting to get a look at a set of valuable prints at the home of an old customer. But when he arrives, he finds himself complicit in a sort of ruse with the blind man’s family. The prints have been sold long ago. The pages in the folios still so lovingly turned by the owner’s hands are blank. The story has the subtitle ‘An Anecdote from the Years of Inflation in Germany’ — on that level, the metaphor is perhaps a little too direct. Like money, those pages have a value which essentially depends on a sort of collective delusion as to their worth. The story has that heightened quality of anguish that is common to Zweig’s work. It is essentially an overwritten, over-dramatised rendition of a poetic image; but the image is haunting regardless.

Twenty-Four Hours in a Woman’s Life is a little more developed. It is tempting to call it cinematic, given that it is so driven with the power of a direct, silent image — in this case a figure glimpsed repeatedly from across a street, or across a room. That said, as with all the stories in this collection it uses a frame narrative. After a minor scandal in a country hotel, an older woman recounts to the narrator an event from years ago. She tried to help a man, a gambler, who had lost a huge amount of money; she ended up falling for him; he ran away; she couldn’t stop him gambling. As a conventional story it is perhaps the most complete thing here. It is also madly overwrought. Zweig was popular in his lifetime but he was not always well-liked, and in this story it’s easy to see why. Every emotion is heightened to breaking point.

Incident on Lake Geneva is comparatively slight, and highly restrained. It is not much more than ten pages long. In the year 1918, a naked man is found by a fisherman, clinging to a set of broken spars; when he is brought ashore, only the ex-manager of the local hotel can speak to him in his native Russian. He is a nameless conscripted soldier who somehow became separated from his regiment, and is entirely lost. It is unclear how exactly he came to be on Lake Geneva — it seems he picked west when he should have wandered east. At any rate he is stranded in neutral Switzerland — he cannot leave without traversing other non-neutral countries. He is distraught and, in the end, he drowns himself in the lake. The story is a bleak, minimal thing. It concludes on a stark image: ‘…a cheap wooden cross was placed on his grave, one of those little crosses marking the fate of nameless men that cover our continent from end to end.’

A Game of Chess is perhaps one of Zweig’s most famous stories. (Oddly, it has had various titles in English under various translators: ‘The Royal Game’, ’A Chess Story’, ‘Chess: a Novel’ or sometimes simply ‘Chess’.) The narrator is on a ship bound for Buenos Aires when he discovers that a famous chess grandmaster named Czentovic is on board. Czentovic’s story is well-known: he was the uneducated son of a poor peasant when his matchless talent for the game became apparent. The narrator is fascinated by this imposing, uncouth figure, and in an effort to draw him into a game he falls in with an arrogant passenger wealthy enough to put up enough cash to draw Czentovic’s attention. The two of them challenge him as a team, and they are almost beaten when they draw the attention of a third — a nervous stranger named Dr B who has his own uncanny gift for the game. He claims not to have played for twenty-five years, and his advice seems to come from a place of desperation, but he seems like the only one capable of defeating Czentovic. Soon enough he tells his own story.

Dr B was resident in Austria when the Nazis annexed that country. He was taken prisoner by the Gestapo, who believed he was keeping information from them regarding the old Austrian monarchy; being an otherwise respectable middle-class citizen, he was kept under arrest in the relative comfort of a hotel room. But with nobody to talk to and nothing to read or watch or do, his solitary confinement became tortuous. It is a haunting picture of isolation:

‘I lived like a diver in a glass bell in the black ocean of silence, a diver who guesses that the cable connecting him with the world above is severed and he will never be drawn back up from the soundless deep.’

The most affecting image here is not the darkness or the silence — if those can be called images — but the glass bell. The thing which, in spite of everything around it, keeps us aware that there is some distinction between the self and the void. It is from the awareness of this distinction that the pain arrives.

One day Dr B finds solace. He steals a book from the coat pocket of an officer which turns out to be a book of chess problems. At first he is disappointed, not having any pieces or a board, but eventually he becomes fully proficient in playing the game entirely in his head. For a while he becomes happy and mentally stronger — but he cannot rid himself of his unspoken obsession with chess. The 150 problems in the book soon become exhausted, and to maintain his interest he is forced to play against himself.

‘If black and white are one and the same person, a preposterous situation is produced in which a single mind is supposed both to know something and not to know it, so that its white self should, by self-command, forget all the aims and intentions of its black self a minute earlier. The premise for such dual thinking is a totally split consciousness, with the brain’s functions being switched on and off like a mechanical apparatus. Wanting to play chess against oneself is thus as much of a paradox as wanting to jump over one’s own shadow.’

Dr B describes the effect as akin to a split personality. But it is not simply a duality — to compute every one of the many alternative moves effectively requires a multiplication into countless simultaneous selves. The strain becomes too much. After a violent attack on a guard, he ends up in a hospital. Eventually, with some help from a benevolent doctor, he is released. He leaves Austria and tries to forget about chess entirely.

A Game of Chess was the last story Zweig ever wrote. He and his wife had been living in exile in South America during the second world war; a day after posting the manuscript to his publishers, they committed suicide. It is hard to avoid thinking about this while reading this story. At first it seems much like most of his other stories — the format is the same, with the heart of the matter being framed as an encounter with a stranger in some marginal travelling space. But where the drama should be is only a terrible void. There are no questions of shame or moral or ethical responsibility; there is only a man kept in a room forever, slowly losing his mind.

The coda of the story is, as you might expect, a match between Dr B and Czentovic. The latter finds a weakness in B’s otherwise impregnable approach — B must play quickly. He works to the speed of his own brain, and so any kind of forced delay in between moves becomes intolerable. And so Czentovic begins to take longer and longer to move until B begins to become confused. Errors are forced from his opponent. He loses. And in this, we glimpse something uniquely cruel. It is not so much that Czentovic behaved in an underhand way because he couldn’t find a way to win on his own terms — that much might be expected from any cunning sportsman. The cruelty comes from the spectacle of a man finding another man’s weak point and pressing down on it with all his strength. It is a uniquely horrific sort of exploitation. But this is what competition does to us. Perhaps society relies on men like Czentovic in order to go on functioning.

The chess games that went on in Dr B’s head were sustained by the idea of constant, total multiplicity: given that both sides were always ultimately B’s side, there could be no real process of elimination — no winners and losers. There could only be an endless selection of moves, categorised as ideal, optimal or otherwise. The confusion would become total, but he could never really defeat himself when the only opponent was his own expectations. But every game of chess that happens in the world outside B’s head must result in the ultimate submission of an individual. Czentovic understands this, and places B in a situation which he cannot survive. It is not sufficient to calculate the perfect move from every given variation when you suddenly find you have forgotten the rules.

3 notes

·

View notes