#Clann Somhairle

Text

8th October, 1275- The Battle of Ronaldsway

(The area around Ronaldsway, at the south end of the Isle of Man, from the air. Picture from Wikimedia Commons)

Got another battle for you today folks, in keeping with the fact that earlier the Battle of Largs was covered on this blog. That battle, though perhaps not quite so game-changing and pivotal in British history as some sources would have us believe, was still an important moment in the process that saw sovereignty over the islands and western seaboard pass from Norway to the Scottish Crown. With the death of Haakon IV in late 1263, any hopes the Norwegians had of soon resuming their campaign and recouping losses were stymied and King Alexander III quickly capitalised on the situation, sending a force into the Hebrides under the Earl of Buchan and Alan Durward, whose forces simultaneously wreaked devastation and brought home the message of Scottish ascendancy. Hostages were taken for good behaviour and while some of the Hebridean rulers still refused to give into Scottish demands of overlordship, others, including several notable members of the House of Somerled, came into the king of Scotland’s peace more readily.

The story of how the Western Isles were incorporated into the kingdom of Scotland is reasonably well known- or at least the popular, if not wholly accurate and somewhat sanitised, version of the story is more likely to be covered in a Scottish history class than that of the Isle of Man. Nonetheless for a short while this territory also came under the control of the Scottish Crown. At around the same time as Buchan and Durward were sent into the Hebrides, an expedition was also fitted out for the Isle of Man. However, Magnus Olafsson, the King of Man, who was probably quite rightly anxious to avoid a Scottish army being set loose in his own land, pre-empted Alexander’s intervention and met with the king of Scots at Dumfries. There, he did homage and received Alexander’s promise of protection and shelter in Scotland should the king of Norway attempt to take reprisals against him, in return for agreeing to provide military service of ten galleys.

How this new relationship between the kings of Man and Scotland would have panned out in time is impossible to say, as Magnus died at Castle Rushen in late 1265. After this, control of Mann was put in the hands of a succession of royal bailiffs (Lewis and Skye, which were also part of the kingdom of Mann, were put under the control of the Crown and the Earl of Ross respectively) and Alexander’s sovereignty over the island was confirmed by Norway as a result of the Treaty of Perth in 1266. At some point seven hostages were taken for good behaviour as well, and kept by the Sheriff of Dumfries on behalf of the king. To all intents and purposes, Man was to be treated as a possession of the Scottish Crown, whether the Manx liked it or not (this also must have stuck in the throat of the king of England, who lost the opportunity to finally bring Mann under English control as a result of being distracted by domestic strife). However while there was little significant trouble in the Hebrides in the decades after the Treaty of Perth, Man was a different matter and not only were the baillies unpopular, but in general the island’s loss of autonomy and subjugation to the Scottish Crown did not go down well. And thus we are brought to the autumn of 1275, when that simmering discontent came to a head and the Manxmen rose in revolt.

(A seal of Alexander III of Scotland, last king of the House of Dunkeld)

The leader of this movement was Guðrøðr Magnusson (name may also be rendered as Godfrey or Godred), an illegitimate son of the late Magnus, who appears to have been viewed by the majority of the Manx political community as the right man to succeed his father. Quickly gathering support, he soon seized the main castles and strongholds on the island, turfing out the Scots there, and making a bid to reestablish the primacy of the Crovan dynasty. Members of this kindred had ruled in Mann since at least the twelfth century, though at other times their power also extended to the Outer Hebrides, especially Lewis (their main competitors, meanwhile, were the branches of the Mac Somhairle clan in the Inner Hebrides and Argyll- who gave rise to the MacDonalds, MacDougalls, and MacRuaidhris- whose members had occasionally also ruled in Mann). But Godred’s attempts to claim the kingship of Mann that his ancestors once held, naturally aroused the wrath of Alexander III, who immediately acted to prevent the situation getting any further out of hand.

Having raised a force from Galloway and the Hebrides, a fleet was soon on its way south to Mann, landing at Ronaldsway on the south side of the island on the seventh of October. Its leaders were King Alexander’s second cousin John de Vesci, lord of Alnwick; John ‘the Black’ Comyn, lord of Badenoch; Alexander MacDougall lord of Argyll, whose sister had been married to the late Magnus Olafsson; Alan MacRuairi, who twelve years earlier had raided the west coast of Scotland on behalf of Hakon IV of Norway; and Alan, a son of the Earl of Atholl and grandson to Roland/Lachlan of Galloway. Of these the last had already been one of the Crown’s bailiffs of Mann, while two more- MacDougall and MacRuairi- belonged to two of the most prominent septs of the House of Somerled, and their role in the suppression of the Manx revolt says a lot about Alexander’s new power in the Hebrides and on the west coast of the Scottish mainland (nevertheless, Alan MacRuairi’s older brother Dubhgall, the head of the MacRuairis, remained in rebellion and had taken himself off to plunder Ireland a few years before, so not everyone was wholly happy with the situation in the Hebrides, even if it was more accepted than in Mann). Meanwhile the ability to raise men in the Hebrides and Galloway was a testament to the strength of the campaigns of Alexander III and his father respectively in those parts, and the Hebridean galleys were a strong addition to the naval power of the Scottish Crown, which had already shown its ability to exploit the advantages of the galley in its earlier campaigns in the west.

Sources for the Manx side of things are even less informative, though for all his early success Guðrøðr’s force does not seem to have been anywhere near as well-equipped as its enemy. When the Scots landed on the seventh, they sent a peace embassy to offer terms if the Manx surrendered, but Guðrøðr and his counsellors firmly rejected this option. Early the next day- the eighth of October- battle was joined before the sun was even in the sky. It is perhaps rather disappointing, given all the lead-up, that Guðrøðr’s short rebellion ended so swiftly and that the skirmish can be summed up in a few sentences, but the sources, though unfortunately short, make it clear that Ronaldsway was an overwhelming defeat for the Manxmen. Accounts of the battle describe the latter as being ‘naked and unarmed’ and they were almost immediately beaten back by the crossbowmen, archers, and other soldiers of the Scots. Very soon they turned and fled, with the Scots in hot pursuit, cutting down any they could catch and not stopping to spare people on account of sex or rank, to the result that over five hundred are alleged to have died in the battle itself. As Ronaldsway is, even today, very close to the important settlement of Castletown (so named for Castle Rushen, then the main political centre of the island), the flight of the Manx brought the Scots into contact with non-combatants and, both in the chase and after the battle was technically over, the invaders brought destruction to the area. As well as slaying many, they are also supposed to have sacked Rushen Abbey, a significant foundation of the Crovan dynasty and a hugely important religious centre for the Isle of Man.

The Chronicle of Man provided a versified toll of the dead:

‘Ten L’s, three X’s, with five and two to fall,

Manxmen take care lest future evils call.’

Or, in Latin:

‘L decies, X ter et penta, duo cecidere,

Mannica gens de te dampua futura cave.’

(Castle Rushen, in the thirteenth century the main political centre of the Isle of Man, and not far from Ronaldsway. Not my picture.)

Scottish control was quickly- and brutally- reestablished over Mann, while Guðrøðr, is supposed to have fled to Wales with his wife and followers. He was not to be the last of the Crovan dynasty to lay claim to Mann, but for the rest of Alexander III’s reign the island does not appear to have caused any significant trouble. To the Scottish Crown this settled the matter and the young Prince Alexander, son of the Scottish king, was named lord of Man until his early death in 1284, though it is doubtful if he ever played much active role in its governance and the real administration of the island was once again placed in the hands of bailiffs.

However, some historians argue that the aftermath of the Battle of Ronaldsway, since it can hardly have inspired positive feelings towards Scotland, may have promoted the further growth of an anti-Scottish faction in the Manx political community. When Margaret- the infant daughter of Eric II of Norway and granddaughter of Alexander III- inherited the throne of Scotland upon the death of her maternal grandfather in 1286, she also succeeded to the title Lady of Mann. However, when her great-uncle Edward I of England annexed the island a little while before her premature death in September of 1290, nobody on the Isle of Man appears to have complained. After all, the Battle of Ronaldsway- and the destruction that followed- had only occurred fifteen years before, and even prior to that the majority of the Manx had not shown any particular enthusiasm for Scottish sovereignty. The territory was formally restored to King John by Edward I in 1293, though quite some time after the rest of the Scottish realm, and was to pass back and forth between Scotland and England for several more decades, but after the mid-fourteenth century Scottish claims to Mann were largely abandoned and at the end of the century it formally came under English control. The Crovan dynasty, however, would never again hold the title Kings of Mann.

(References below cut)

The Furness continuation of William of Newburgh’s ‘Historia Reru Anglicarum’ in ‘Chronicles of the Reigns of Stephen, Henry II and Richard’, ed. Richard Howlett

The Chronicle of Man in ‘Monumenta de Insula Manniae, or a Collection of National Documents Relating to the Isle of Man’, transl. and ed. J. R. Oliver

‘Early Sources of Scottish History’, A.O. Anderson

John of Fordun’s ‘Chronica Gentis Scotorum’, ed. by W. F. Skene

‘Kingship and Unity: Scotland 1000-1306′, G.W.S. Barrow

‘The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland’s Western Seaboard, c. 1100- c.1336′, R. Andrew MacDonald

“The Wars of Scotland, 1214-1371″, by Michael Brown

#Isle of Man#Manx history#Scottish history#Scotland#English history#British Isles#thirteenth century#Magnus Olafsson#Alexander III#Godred Magnusson#Crovan dynasty#House of Somerled#Clann Somhairle#Western Isles#warfare#battles#Norway#Kingdom of Mann and the Isles#House of Dunkeld

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

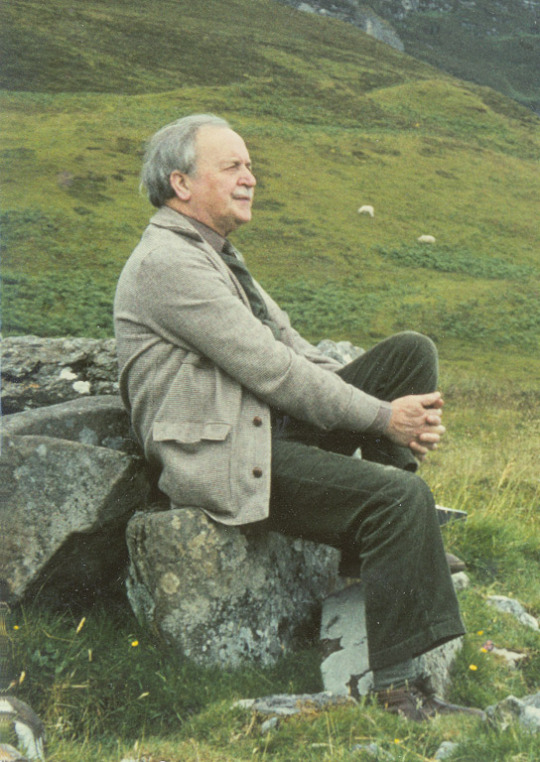

On October 26th 1911 the Gaelic poet, Sorley MacLean, was born on the island of Raasay, the same island my own ancestors originated.

Maclean was born at Osgaig on the island into a Gaelic speaking community. He was the second of five sons born to Malcolm and Christina MacLean. His brothers were John Maclean, a schoolteacher and later rector of Oban High School, who was also a piper, Calum Maclean, a noted folklorist and ethnographer; and Alasdair and Norman, who became GP's. His name in Gaelic was Somhairle MacGill-Eain.

At home, he was steeped in Gaelic culture and beul-aithris (the oral tradition), especially old songs. His mother, a Nicolson, had been raised near Portree, although her family was of Lochalsh origin her family had been involved in Highland Land League activism for tenant rights. His father, who owned a small croft and ran a tailoring business,[12]:16 had been raised on Raasay, but his family was originally from North Uist and, before that, Mull. Both sides of the family had been evicted during the Highland Clearances, of which many people in the community still had a clear recollection.

What MacLean learned of the history of the Gaels, especially of the Clearances, had a significant impact on his worldview and politics. Of especial note was MacLean's paternal grandmother, Mary Matheson, whose family had been evicted from the mainland in the 18th century. Until her death in 1923, she lived with the family and taught MacLean many traditional songs from Kintail and Lochalsh. As a child, MacLean enjoyed fishing trips with his aunt Peigi, who taught him other songs.[9] Unlike other members of his family, MacLean could not sing, a fact that he connected with his impetus to write poetry.

Sorley was brought up as a follower of the Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland, now if you think the Wee Free are strict, these guys think that The Wee Free are too lenient, but Sorley says he gave up the religion for socialism at the age of twelve as he refused to accept that a majority of human beings were consigned to eternal damnation. He was educated at Raasay Primary School and Portree Secondary School. In 1929, he left home to attend the University of Edinburgh.

While studying at Edinburgh University he encountered Hugh Macdiarmid who inspired him to write poetry. However, Maclean chose the Gaelic of his childhood rather than Scots.

After fighting in North Africa during World War II he embarked on his life-long career as a school teacher - working in Mull, Edinburgh and Plockton.

Maclean was one of the finest writers of Gaelic in the 20th century. He drew upon its rich oral tradition to create innovative and beautiful poetry about the Scottish landscape and history. He was also an accomplished love poet. However, writing in Gaelic limited his audience so he began to translate his own work into English. In 1977 a bilingual edition of his selected poems appeared - followed by the collected poems in 1989.

His fame as a poet began to spread during the 1970s - helped by the appearance of his work in Gordon Wright's Four Points of a Saltire. Seamus Heaney, who first met Maclean at a poetry reading at the Abbey Theatre Dublin, was one of his greatest admirers and subsequently worked on translations of his work.

One of Maclean's most celebrated poems is Hallaig which concerns the enforced clearance of the inhabitants of the township of Hallaig (Raasay) to Australia. A film, Hallaig, was made in 1984 by Timothy Neat, including a discussion by MacLean of the dominant influences on his poetry, with commentary by Smith and Heaney, and substantial passages from the poem and other work, along with extracts of Gaelic song

In 1990 Maclean received the Queen's Gold Medal for poetry. He died in 1996 at the age of 85.‘.

Tha tìm, am fiadh, an coille Hallaig’

Tha bùird is tàirnean air an uinneig

trom faca mi an Àird Iar

’s tha mo ghaol aig Allt Hallaig

’na craoibh bheithe, ’s bha i riamh

eadar an t-Inbhir ’s Poll a’ Bhainne,

thall ’s a-bhos mu Bhaile Chùirn:

tha i ’na beithe, ’na calltainn,

’na caorann dhìrich sheang ùir.

Ann an Sgreapadal mo chinnidh,

far robh Tarmad ’s Eachann Mòr,

tha ’n nigheanan ’s am mic ’nan coille

a’ gabhail suas ri taobh an lòin.

Uaibreach a-nochd na coilich ghiuthais

a’ gairm air mullach Cnoc an Rà,

dìreach an druim ris a’ ghealaich –

chan iadsan coille mo ghràidh.

Fuirichidh mi ris a’ bheithe

gus an tig i mach an Càrn,

gus am bi am bearradh uile

o Bheinn na Lice fa sgàil.

Mura tig ’s ann theàrnas mi a Hallaig

a dh’ionnsaigh Sàbaid nam marbh,

far a bheil an sluagh a’ tathaich,

gach aon ghinealach a dh’fhalbh.

Tha iad fhathast ann a Hallaig,

Clann Ghill-Eain’s Clann MhicLeòid,

na bh’ ann ri linn Mhic Ghille Chaluim:

chunnacas na mairbh beò.

Na fir ’nan laighe air an lèanaig

aig ceann gach taighe a bh’ ann,

na h-igheanan ’nan coille bheithe,

dìreach an druim, crom an ceann.

Eadar an Leac is na Feàrnaibh

tha ’n rathad mòr fo chòinnich chiùin,

’s na h-igheanan ’nam badan sàmhach

a’ dol a Clachan mar o thus.

Agus a’ tilleadh às a’ Chlachan,

à Suidhisnis ’s à tir nam beò;

a chuile tè òg uallach

gun bhristeadh cridhe an sgeòil.

O Allt na Feàrnaibh gus an fhaoilinn

tha soilleir an dìomhaireachd nam beann

chan eil ach coitheanal nan nighean

a’ cumail na coiseachd gun cheann.

A’ tilleadh a Hallaig anns an fheasgar,

anns a’ chamhanaich bhalbh bheò,

a’ lìonadh nan leathadan casa,

an gàireachdaich ‘nam chluais ’na ceò,

’s am bòidhche ’na sgleò air mo chridhe

mun tig an ciaradh air caoil,

’s nuair theàrnas grian air cùl Dhùn Cana

thig peilear dian à gunna Ghaoil;

’s buailear am fiadh a tha ’na thuaineal

a’ snòtach nan làraichean feòir;

thig reothadh air a shùil sa choille:

chan fhaighear lorg air fhuil rim bheò.

Hallaig

Translator: Sorley MacLean

‘Time, the deer, is in the wood of Hallaig’

The window is nailed and boarded

through which I saw the West

and my love is at the Burn of Hallaig,

a birch tree, and she has always been

between Inver and Milk Hollow,

here and there about Baile-chuirn:

she is a birch, a hazel,

a straight, slender young rowan.

In Screapadal of my people

where Norman and Big Hector were,

their daughters and their sons are a wood

going up beside the stream.

Proud tonight the pine cocks

crowing on the top of Cnoc an Ra,

straight their backs in the moonlight –

they are not the wood I love.

I will wait for the birch wood

until it comes up by the cairn,

until the whole ridge from Beinn na Lice

will be under its shade.

If it does not, I will go down to Hallaig,

to the Sabbath of the dead,

where the people are frequenting,

every single generation gone.

They are still in Hallaig,

MacLeans and MacLeods,

all who were there in the time of Mac Gille Chaluim:

the dead have been seen alive.

The men lying on the green

at the end of every house that was,

the girls a wood of birches,

straight their backs, bent their heads.

Between the Leac and Fearns

the road is under mild moss

and the girls in silent bands

go to Clachan as in the beginning,

and return from Clachan,

from Suisnish and the land of the living;

each one young and light-stepping,

without the heartbreak of the tale.

From the Burn of Fearns to the raised beach

that is clear in the mystery of the hills,

there is only the congregation of the girls

keeping up the endless walk,

coming back to Hallaig in the evening,

in the dumb living twilight,

filling the steep slopes,

their laughter a mist in my ears,

and their beauty a film on my heart

before the dimness comes on the kyles,

and when the sun goes down behind Dun Cana

a vehement bullet will come from the gun of Love;

and will strike the deer that goes dizzily,

sniffing at the grass-grown ruined homes;

his eye will freeze in the wood,

his blood will not be traced while I live.

)

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

St Brendan's chapel

Also called Kilbrannan Chapel or Skipness Chapel, is a medieval chapel near Skipness, Argyll and Bute, Scotland. The chapel was built in the late 13th or early 14th century by Clann Somhairle and was dedicated to St. Brendan.

69 notes

·

View notes