#Curtiss P-40 in Java

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

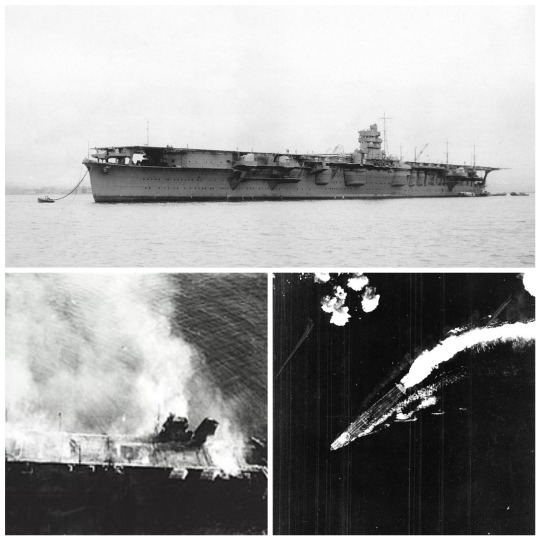

On February 27, 1942, the aircraft tender, USS Langley (AV-3), was carrying 32 U.S. Army Air Force Curtiss P-40 "Warhawk" aircraft for the defense of Java when she was bombed by Japanese naval land attack planes about 75 miles south of Tjilatjap. Along with Langley was the freighter Sea Witch, carrying an additional 27 Curtiss P-40 "Warhawk" aircraft, and the destroyer escorts USS Whipple (DD-217) and USS Edsall (DD-219). Due to the damage received by the Japanese aircraft, Langley was scuttled by Whipple. Seen from USS WHIPPLE (DD-217)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

• IJN Aircraft Carrier Hiryū

Hiryū (飛龍, "Flying Dragon") was an aircraft carrier built for the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) during the 1930s. Generally regarded as the only ship of her class, she was built to a modified Sōryū design.

Hiryū was one of two large carriers approved for construction under the 1931–32 Supplementary Program. Originally designed as the sister ship of Sōryū, her design was enlarged and modified in light of the Tomozuru and Fourth Fleet Incidents in 1934–1935 that revealed many IJN ships were top-heavy, unstable and structurally weak. Her forecastle was raised and her hull strengthened. Other changes involved increasing her beam, displacement, and armor protection. The ship had a length of 227.4 meters (746 ft 1 in) overall, a beam of 22.3 meters (73 ft 2 in) and a draft of 7.8 meters (25 ft 7 in). She displaced 17,600 metric tons (17,300 long tons) at standard load and 20,570 metric tons (20,250 long tons) at normal load. Her crew consisted of 1,100 officers and enlisted men. Hiryū was fitted with four geared steam turbine sets with a total of 153,000 shaft horsepower (114,000 kW). Hiryū carried 4,500 metric tons (4,400 long tons) of fuel oil which gave her a range of 10,330 nautical miles (19,130 km; 11,890 mi) at 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph). The boiler uptakes were trunked to the ship's starboard side amidships and exhausted just below flight deck level through two funnels curved downward.

The carrier's 216.9-meter (711 ft 7 in) flight deck was 27 meters (88 ft 6 in) wide and overhung her superstructure at both ends, supported by pairs of pillars. Hiryū was one of only two carriers ever built whose island was on the port side of the ship (Akagi was the other). It was also positioned further to the rear and encroached on the width of the flight deck, unlike Sōryū. The flight deck was only 12.8 meters (42 ft) above the waterline and the ship's designers kept this figure low by reducing the height of the hangars. The upper hangar was 171.3 by 18.3 meters (562 by 60 ft) and had an approximate height of 4.6 meters (15 ft); the lower was 142.3 by 18.3 meters (467 by 60 ft) and had an approximate height of 4.3 meters (14 ft). Together they had an approximate total area of 5,736 square meters (61,740 sq ft). This caused problems in handling aircraft because the wings of a Nakajima B5N "Kate" torpedo bomber could neither be spread nor folded in the upper hangar. Aircraft were transported between the hangars and the flight deck by three elevators, the forward one abreast the island on the centerline and the other two offset to starboard.

Hiryū's primary anti-aircraft (AA) armament consisted of six twin-gun mounts equipped with 12.7-centimeter Type 89 dual-purpose guns mounted on projecting sponsons, three on either side of the carrier's hull. When firing at surface targets, the guns had a range of 14,700 meters (16,100 yd); they had a maximum ceiling of 9,440 meters (30,970 ft) at their maximum elevation of +90 degrees. Their maximum rate of fire was 14 rounds a minute, but their sustained rate of fire was approximately eight rounds per minute. The ship was equipped with two Type 94 fire-control directors to control the 12.7-centimeter (5.0 in) guns, one for each side of the ship; the starboard-side director was on top of the island and the other director was positioned below flight deck level on the port side. The ship's light AA armament consisted of seven triple and five twin-gun mounts for license-built Hotchkiss 25 mm Type 96 AA guns. Two of the triple mounts were sited on a platform just below the forward end of the flight deck. Hiryū had a waterline belt with a maximum thickness of 150 millimeters (5.9 in) over the magazines that reduced to 90 millimeters (3.5 in) over the machinery spaces and the gas storage tanks. It was backed by an internal anti-splinter bulkhead. The ship's deck was 25 millimeters (0.98 in) thick over the machinery spaces and 55 millimeters (2.2 in) thick over the magazines and gas storage tanks.

Following the Japanese ship-naming conventions for aircraft carriers, Hiryū was named "Flying Dragon". The ship was laid down at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal on July 8th, 1936, launched on November 16th, 1937 and commissioned on July 5th, 1939. She was assigned to the Second Carrier Division on November 15th. In September 1940, the ship's air group was transferred to Hainan Island to support the Japanese invasion of French Indochina. In February 1941, Hiryū supported the blockade of Southern China. Two months later, the 2nd Carrier Division, commanded by Rear Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi, was assigned to the First Air Fleet, or Kido Butai, on April 10th. Hiryū returned to Japan on August 7th and began a short refit that was completed on September 15th. She became flagship of the Second Division from September 22nd to October 26th while Sōryū was refitting. In November 1941, the IJN's Combined Fleet, commanded by Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, prepared to participate in Japan's initiation of a formal war with the United States by conducting a preemptive strike against the United States Navy's Pacific Fleet base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. On November 22nd, Hiryū, commanded by Captain Tomeo Kaku, and the rest of the Kido Butai, under Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo and including six fleet carriers from the First, Second, and Fifth Carrier Divisions, assembled in Hitokappu Bay at Etorofu Island. The fleet departed Etorofu, and followed a course across the north-central Pacific to avoid commercial shipping lanes. Now the flagship of the Second Carrier Division, the ship embarked 21 Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters, 18 Aichi D3A "Val" dive bombers, and 18 Nakajima B5N "Kate" torpedo bombers. From a position 230 nmi (430 km; 260 mi) north of Oahu, Hiryū and the other five carriers launched two waves of aircraft on the morning of December 7th, 1941 Hawaiian time. In the first wave, 8 B5N torpedo bombers were supposed to attack the aircraft carriers that normally berthed on the northwest side of Ford Island, but none were in Pearl Harbor that day; 4 of the B5N pilots diverted to their secondary target, ships berthed alongside "1010 Pier" where the fleet flagship was usually moored. That ship, the battleship Pennsylvania, was in drydock and its position was occupied by the light cruiser Helena and the minelayer Oglala; all four torpedoes missed. The other four pilots attacked the battleships West Virginia and Oklahoma. The remaining 10 B5Ns were tasked to drop 800-kilogram (1,800 lb) armor-piercing bombs on the battleships berthed on the southeast side of Ford Island ("Battleship Row") and may have scored one or two hits on them, in addition to causing a magazine explosion aboard the battleship Arizona that sank her with heavy loss of life. The second wave consisted of 9 Zeros and 18 D3As, They strafed the airfield, and shot down two Curtiss P-40 fighters attempting to take off when the Zeros arrived and a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bomber that had earlier diverted from Hickam Army Airfield, and also destroyed a Stinson O-49 observation aircraft on the ground for the loss of one of their own. The D3As attacked various ships in Pearl Harbor, but it is not possible to identify which aircraft attacked which ship.

While returning to Japan after the attack, Vice Admiral Chūichi Nagumo, commander of the First Air Fleet, ordered that Sōryū and Hiryū be detached on December 16th to attack the defenders of Wake Island who had already defeated the first Japanese attack on the island. The two carriers reached the vicinity of the island on December 21st and launched 29 D3As and 2 B5Ns, escorted by 18 Zeros, to attack ground targets. They encountered no aerial opposition and launched 35 B5Ns and 6 A6M Zeros the following day. The carriers arrived at Kure on 29 December. They were assigned to the Southern Force on January 8th, 1942 and departed four days later for the Dutch East Indies. The ships supported the invasion of the Palau Islands and the Battle of Ambon, attacking Allied positions on the island on January 23rd with 54 aircraft. Four days later the carriers detached 18 Zeros and 9 D3As to operate from land bases in support of Japanese operations in the Battle of Borneo. Hiryū and Sōryū arrived at Palau on January 28th and waited for the arrival of the carriers Kaga and Akagi. All four carriers departed Palau on February 15th and launched air strikes against Darwin, Australia, four days later. Hiryū contributed 18 B5Ns, 18 D3As, and 9 Zeros to the attack. Her aircraft attacked the ships in port and its facilities, sinking or setting on fire three ships and damaging two others. Hiryū and the other carriers arrived at Staring Bay on Celebes Island on February 21st to resupply and rest before departing four days later to support the invasion of Java. On March 1st, 1942, the ship's D3As damaged the destroyer USS Edsall badly enough for her to be caught and sunk by Japanese cruisers. Later that day the dive bombers sank the oil tanker USS Pecos. Two days later, they attacked Christmas Island and Hiryū's aircraft sank the Dutch freighter Poelau Bras before returning to Staring Bay on March 11th to resupply and train for the impending Indian Ocean raid.

On March 26th, the five carriers of the First Air Fleet departed from Staring Bay; they were spotted by a Catalina about 350 nautical miles (650 km; 400 mi) southeast of Ceylon on the morning of April 4th. Six of Hiryū's Zeros were on Combat Air Patrol (CAP) and helped to shoot it down. Hiryū contributed 18 B5Ns and 9 Zeros to the force; the latter encountered a flight of 6 Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers from 788 Naval Air Squadron en route and shot them all down without loss. The Japanese aircraft encountered defending Hawker Hurricane fighters from Nos. 30 and 258 Squadrons RAF over Ratmalana airfield and Hiryū's fighters claimed to have shot down 11 with 3 Zeros damaged, although the fighters from the other carriers also made claims. On the morning of April 9th, Hiryū's CAP shot down another Catalina attempting to locate the fleet and, later that morning, contributed 18 B5Ns, escorted by 6 Zeros, to the attack on Trincomalee. The fighters engaged 261 Squadron RAF, claiming to have shot down two with two more shared with fighters from the other carriers. On April 19th, while transiting the Bashi Straits between Taiwan and Luzon en route to Japan, Hiryū, Sōryū, and Akagi were sent in pursuit of the American carriers Hornet and Enterprise, which had launched the Doolittle Raid against Tokyo. They found only empty ocean, as the American carriers had immediately departed the area to return to Hawaii. The carriers quickly abandoned the chase and dropped anchor at Hashirajima anchorage on April 22nd. Having been engaged in constant operations for four and a half months, the ship, along with the other three carriers of the First and Second Carrier Divisions, was hurriedly refitted and replenished in preparation for the Combined Fleet's next major operation, scheduled to begin one month hence. While at Hashirajima, Hiryū's air group was based ashore at Tomitaka Airfield, near Saiki, Ōita, and conducted flight and weapons training with the other First Air Fleet carrier units.

Concerned by the US carrier strikes in the Marshall Islands, Lae-Salamaua, and the Doolittle raids, Yamamoto was determined to force the US Navy into a showdown to eliminate the American carrier threat. He decided to invade and occupy Midway Atoll, which he was sure would draw out the American carriers to defend it. The Japanese codenamed the Midway invasion Operation MI. Unknown to the Japanese, the US Navy had divined the Japanese plan by breaking its JN-25 code and had prepared an ambush using its three available carriers, positioned northeast of Midway. On May 25th, 1942, Hiryū set out with the Combined Fleet's carrier striking force in the company of Kaga, Akagi, and Sōryū, which constituted the First and Second Carrier Divisions, for the attack on Midway. Her aircraft complement consisted of 18 Zeros, 18 D3As, and 18 B5Ns. on June 4th, 1942, Hiryū's portion of the 108-plane airstrike was an attack on the facilities on Sand Island with 18 torpedo bombers, one of which aborted with mechanical problems, escorted by nine Zeros. The air group suffered heavily during the attack: two B5Ns were shot down by fighters, with a third falling victim to AA fire. The carrier also contributed 3 Zeros to the total of 11 assigned to the initial CAP over the four carriers. By 07:05, the carrier had 6 fighters with the CAP which helped to defend the Kido Butai from the first US attackers from Midway Island at 07:10. Hiryū reinforced the CAP with launches of 3 more Zeros at 08:25. These fresh Zeros helped defeat the next American air strike from Midway. Although all the American air strikes had thus far caused negligible damage, they kept the Japanese carrier forces off-balance as Nagumo endeavored to prepare a response to news, received at 08:20, of the sighting of American carrier forces to his northeast.

Hiryū began recovering her Midway strike force at around 09:00 and finished shortly by 09:10. The landed aircraft were quickly struck below, while the carriers' crews began preparations to spot aircraft for the strike against the American carrier forces. The preparations were interrupted at 09:18, when the first attacking American carrier aircraft were sighted. Hiryū launched another trio of CAP Zeros at 10:13 after Torpedo Squadron 3 (VT-3) from Yorktown was spotted. Two of her Zeros were shot down by Wildcats escorting VT-3 and another was forced to ditch. While VT-3 was still attacking Hiryū, American dive bombers arrived over the Japanese carriers almost undetected and began their dives. It was at this time, around 10:20, that in the words of Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully, the "Japanese air defenses would finally and catastrophically fail." Three American dive bomber squadrons now attacked the three other carriers and set each of them on fire. Hiryū was untouched and proceeded to launch 18 D3As, escorted by six Zeros, at 10:54. Yamaguchi radioed his intention to Nagumo at 16:30 to launch a third strike against the American carriers at dusk (approximately 18:00), but Nagumo ordered the fleet to withdraw to the west. At this point in the battle, Hiryū had only 4 air-worthy dive-bombers and 5 torpedo-planes left. She also retained 19 of her own fighters on board as well as a further 13 Zeros on CAP (a composite force of survivors from the other carriers). At 16:45, Enterprise's dive bombers spotted the Japanese carrier and began to maneuver for good attacking position while reducing altitude. Hiryū was struck by four 1,000-pound (450 kg) bombs, three on the forward flight deck and one on the forward elevator. The explosions started fires among the aircraft on the hangar deck. The forward half of the flight deck collapsed into the hangar while part of the elevator was hurled against the ship's bridge. The fires were severe enough that the remaining American aircraft attacked the other ships escorting Hiryū, albeit without effect, deeming further attacks on the carrier as a waste of time because she was aflame from stem to stern. Beginning at 17:42, two groups of B-17s attempted to attack the Japanese ships without success, although one bomber strafed Hiryū's flight deck, killing several anti-aircraft gunners. Although Hiryū's propulsion was not affected, the fires could not be brought under control. At 21:23, her engines stopped, and at 23:58 a major explosion rocked the ship. The order to abandon ship was given at 03:15, and the survivors were taken off by the destroyers Kazagumo and Makigumo. Yamaguchi and Kaku decided to remain on board as Hiryū was torpedoed at 05:10 by Makigumo as the ship could not be salvaged. Around 07:00, one of Hōshō's Yokosuka B4Y aircraft discovered Hiryū still afloat and not in any visible danger of sinking. The aviators could also see crewmen aboard the carrier, men who had not received word to abandon ship. They finally launched some of the carrier's boats and abandoned ship themselves around 09:00. Thirty-nine men made it into the ship's cutter only moments before Hiryū sank around 09:12, taking the bodies of 389 men with her. The loss of Hiryū and the three other IJN carriers at Midway, comprising two thirds of Japan's total number of fleet carriers and the experienced core of the First Air Fleet, was a strategic defeat for Japan and contributed significantly to Japan's ultimate defeat in the war. In an effort to conceal the defeat, the ship was not immediately removed from the Navy's registry of ships, instead being listed as "unmanned" before finally being struck from the registry on 25 September 1942. The IJN selected a modified version of the Hiryū design for mass production to replace the carriers lost at Midway. Of a planned program of 16 ships of the Unryū class, only 6 were laid down and 3 were commissioned before the end of the war.

#second world war#world war 2#world war ii#wwii#military history#history#long post#naval history#imperial japan#japanese navy#japanese history#aircraft carrier#ships#midway

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

USAAF P-40's in Java

A series of articles focusing on the ill-fated efforts to bolster the Dutch defences against the Japanese onslaught early 1942 . Four squadrons of P-40 Warhawks were sent on a 6000 mile journey - from Brisbane, Australia to Java. Of the 83 that set out, only 30 ever reached their destination. And they went down fighting against overwhelming odds...

Follow all instalments on https://thejavagoldblog.wordpress.com/

#p-40 warhawk#usaaf in Java#US P-40's in Java#USAAF P-40's Pacific#Curtiss P-40#Curtiss P-40 in Australia#Curtiss P-40 in Java#curtiss p-40 warhawk#pacific war#17th Pursuit Sqn on Java#20th Pursuit Squadron on Java#Darwin in WW2#USAAF in Darwin Australia#Curtiss P-40's on Timor

0 notes

Photo

https://pacificeagles.net/defence-port-moresby/

In Defence of Port Moresby

After Rabaul had been captured by the Japanese, Australian forces attempted to consolidate positions on the south coast of New Guinea, particularly at the capital of Port Moresby. With the most skilled and experienced Australian pilots still fighting in Europe and North Africa, the Australian government scrambled to find additional forces to send north. With American forces still making their way across the Pacific, for the time being it was up to the Royal Australian Air Force to stand alone in the defence of Port Moresby.

Existing RAAF strength at Port Moresby was pitiful. Portions of two flying boat squadrons, numbers 11 and 20 Squadron with 6 Catalinas total, and 24 Squadron, a survivor of the Japanese assault on Rabaul that had regrouped at Port Moresby with just 7 Lockheed Hudson medium bombers, comprised the total force available for the defence of the city. This small force was required to not only patrol the approaches to New Guinea to provide early warning of approaching Japanese forces, but also to carry out harassing raids on Rabaul and other enemy positions.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/pacificeagles/33301411092/in/dateposted-public/

With the fall of Rabaul, Port Moresby was within range of Japanese bombers based there. The first raid occurred on the night of the 28th/29th of January, 1942, when H6K Type 97 flying boats from the Yokohama Kokutai appeared over the town in the early hours to carry out a harassing raid. This was followed up on the 2nd of February by an attack during which the Yokohama Ku was joined by 10 of the Chitose Ku’s G3M bombers. With no fighters available, the sole defence was in the form of the anti-aircraft batteries that protected the port and airfield facilities. Damage was on this occasion very light. Initially these raids were unescorted, but soon the Japanese captured Gasmata on the south coast of New Britain, followed a month later by the capture of Lae. Zeros were soon flown into these airfields, from which they could reach not only Port Moresby but also the northern coast of Australia itself.

The small RAAF bomber force did its best to make life difficult for the Japanese. On the night of the 3rd/4th of February, five Catalinas set out for a harassing raid on Rabaul. Chitose Ku A5M fighters attempted a night interception and succeeded in badly damaging one of the flying boats, which was forced to land at Salamaua to make emergency repairs, before returning to Port Moresby a day late. On the 6th, a Hudson was badly damaged on a reconnaissance flight to Rabaul, and had to fly 500 miles back to Port Moresby with three badly wounded crew. For two days starting on the 9th, Hudsons and Catalinas attacked shipping off Gasmata, where the Japanese had just landed. During the second day two Hudsons were shot down by fighters, with 24 Squadron’s skipper SqLdr John Lerew the only survivor – it took him nine days to return to Port Moresby, after he received help from coast watchers.

The first American assistance arrived in the form of the 14th Reconnaissance Squadron, detached from the Hawaiian Air Force specifically to bolster the Australian end of the Hawaii-Australia aerial ferry route. Their first mission was to have been against Rabaul to coincide with the US Navy’s attack on the 21st of February, but when this operation was cancelled the raid was delayed two days. Only five of the assigned nine B-17s made it through abysmal weather to drop bombs on shipping in Simpson Harbour, with indeterminate results.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/pacificeagles/32610911904/in/album-72157681345625026/

The Japanese were also bringing additional bomber forces into the area as the Chitose Kokutai moved more aircraft to Rabaul, where it was joined by the new 4th Kokutai. The 4th was almost wiped out attacking the Lexington, and as a result the 1st Kokutai was transferred from operations in the Indies to reinforce. After a lull the first raid on Port Moresby by this force occurred on the 28th of February, the seaplane base being badly hit with three Catalinas destroyed. The Australians did their best to hit back with what remained of their bombers, mounting a many reconnaissance and harassment missions as they could. It was during a series of these flights that the impending landings at Lae and Salamaua were discovered, resulting in the attack of the 10th of March. The 24th Air Flotilla bomber force launched several raids in support of these landings.

The Allied response to the landings at Lae prompted the Japanese to more aggressively challenge the supply routes to Port Moresby. Flying from the newly captured airfield at Lae, A6M Zeros from the 4th Kokutai’s fighter unit flew to attack Horn Island on the 14th of March in support of a bombing raid. They were challenged by P-40s of the 49th Fighter Group, which were temporarily stationed there whilst transiting to Darwin.

The ‘Tomorrowhawks’

With the Australian situation at Port Moresby looking bleak, the government in Canberra scrambled to find reinforcements to help the garrison. The first batch of P-40 ‘Kittyhawks’ from a large order had arrived at Brisbane, and these were hurriedly assigned to three newly formed squadrons for the defence of New Guinea. Veteran pilots recently returned from the Mediterranean were assigned to lead pilots fresh out of training school as part of 75 Squadron, and the new squadron was given just a few days to familiarise itself with the Curtiss fighter before it was rushed to 7 Mile airfield, the first echelon arriving on the 21st of March. So surprised were the defenders to see the aircraft (which they had derisively nicknamed ‘Tomorrowhawks’ or ‘Neverhawks’) that anti-aircraft crews assumed they were Japanese, and damaged three fighters before they could land.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/pacificeagles/32610910584/in/album-72157681345625026/

Two pilots were immediately ordered into the air to intercept the daily reconnaissance flight from Lae, and the subsequent destruction of a G4M gave the garrison an enormous lift. The very next day, Flight Lieutenant John Jackson, commander of 75 Squadron, led nine of his fighters over the Owen Stanley Mountains in a strafing attack on Lae airfield. Several fighters and bombers were burned on the ground but patrolling Zeros shot down two of the Kittyhawks, with one of the pilots forced to make a month-long trek across New Guinea before he arrived back at Port Moresby.

Realising that the game had changed with the arrival of Australian fighters, the Japanese redoubled their efforts to destroy Port Moresby’s airfields. 19 bombers, the largest raid on the town yet, were sent to attack from high altitude, where the Kittyhawks struggled to meet them due to their lack of supercharged engines. The escorting Zeros were able to attack 75 Squadron with altitude advantage, forcing the Australians to dive away or face destruction. They then strafed 7 Mile, destroying or damaging several Kittyhawks in exchange for one Zero shot down by a ground fire. Other raids occurred over the next few days, with similar results. In just a few days of fighting 75 Squadron had lost 7 out of 17 fighters, and thought was given to withdrawing the inexperienced unit. Further raids over the next few days resulted in less damage, but wore down the defenders still further.

The Japanese began to re-organise their air units prior to the beginning of their second phase offensives. The air units were exhausted following months of activity, and maintenance schedules had fallen by the wayside to the extent that many aircraft were unflyable. There was an inevitable lull in operations as repairs were made and reinforcements brought in. The newly formed 25th Air Flotilla joined the 24th at Rabaul, with five kokutai between them – including the veteran Tainan Ku, which had transferred from the Netherlands East Indies. This force was assembled to win control of the air before the major effort to capture Port Moresby began in May. On the Allied side, American bombers were arriving in Northern Australia in growing numbers, with B-26 Marauders of the 22nd Bomb Group arriving Archerfield in some force and the 19th Bomb Group regrouping nearby following its experiences in Java. In between these two forces was the battered 75 Squadron at 7 Mile.

Reinforcements

Of more immediate interest to the troops at Port Moresby was the arrival of the 3rd Bomb Group’s 8th Bomb Squadron with a few A-24 Banshee bombers. These attacked Salamaua airfield on the 1st of April, planting 500lb bombs on the runway. The Americans even began something of a counter offensive, launching simultaneous raids on Gasmata (by B-25s in their first combat) and Rabaul (by B-17s and 22nd Bomb Group B-26s, also in their first combat) on the 6th of April. One B-26 was lost when it ditched with battle damage, but the crew was recovered by an RAAF Catalina. 75 Squadron returned to Lae a few days later and burned more aircraft on the ground – no protective revetments were available for the Japanese.

American bombers continued raids on Rabaul, in small numbers – half a dozen B-26s, 1 or 2 B-17s at a time. In another first, a squadron of photo-reconnaissance F-4 Lightnings (converted Lockheed P-38s) began operations to keep track of Japanese forces. Success was modest, with the B-26s striking airfields from low level and claiming many aircraft destroyed on the ground. The Marauders also spotted, but failed to sink, the escort carrier Kasuga Maru as it delivered aircraft to Rabaul. On April 18th success was finally achieved when the 22nd Bomb Group managed to sink the transport Komaki Maru just after it unloaded pilots and aircraft from the Tainan Kokutai. This was the first Japanese ship to be sunk in Simpson Harbour.

This American aggression prompted the Japanese to renew their efforts against Port Moresby. With the 1st, 4th and Tainan Kokutai now approaching full strength, plans were laid to prepare the ground for the anticipated invasion of the town planned for early May. On the 21st of April bombers returned to plaster Port Moresby, escorted by Zeros using a new tactic – half the fighters would act as direct escort, whilst the other half would attempt to attack 75 Squadron’s Kittyhawks as they landed following the raid. Three Kittyhawks were lost. During the last 12 days of April a total of 10 raids were mounted against Port Moresby, stretching the defenders to the limit. Aside from the damage done by bombs, strafing Zeros destroyed many aircraft on the ground.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/pacificeagles/33453784505/in/album-72157681345625026/

75 Squadron suffered its blackest day on the 28th of April. The unit had just five Kittyhawks still serviceable, and these rose to challenge the daily raid. Just as they reached the altitude of the incoming G4Ms, escorting Zeros fell on the vulnerable fighters and opened fire on three of them. One was damaged but managed to pull away and return to 7 Mile, the pilot wounded. The other two, one piloted by FL John Jackson, were both shot down with the pilots killed. 75 Squadron had lost its leader, and the unit was shattered with no flyable Kittyhawks remaining. It was withdrawn a few days later, having lost 22 aircraft and 12 pilots killed in 44 days of operations. 26 P-39 Airacobras from the 8th Pursuit Group led by newly promoted LtCol Boyd Wagner, a Philippines veteran and the first USAAF ‘ace’ of the war, arrived to take over the defence of the town. On their first mission the P-39s claimed four Zeros shot down but lost four Airacobras in return.

The reinforcements arrived just in time. American intelligence had analysed Japanese radio traffic and determined that the ‘MO’ Operation to capture Port Moresby was about to be launched. B-26s launched additional raids on Rabaul, hoping to reduce the usefulness of that base during the upcoming battle, but they failed to cause much damage and lost another Marauder in the effort. It would fall to the Navy to make the major effort to forestall the offensive, and in Pearl Harbor Admiral Nimitz had already gathered his powerful carrier forces in the South Pacific especially fr the purposes of blunting the Japanese attack. The stage was set for the first climactic carrier battle of the war, in a place west of New Guinea called the Coral Sea.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The aircraft tender USS Langley (AV-3), which once had been the U. S. Navy's first aircraft carrier as USS Langley (CV-1), is sunk by Japanese aircraft in the Indian Ocean while trying to deliver Curtiss P-40 fighters from Australia to Java.

0 notes