#Elena Gianini Belotti

Text

« SI L’HOMME AVAIT SIMPLEMENT ENVIE D’ÉCOUTER CE QUE LES FEMMES ONT À DIRE D’ELLES-MÊMES, UNE GRANDE PARTIE DES PROBLÈMES ENTRE LES SEXES SERAIT DÉJA RÉSOLUE »

- Du côté des petites filles, 1973, Elena Gianini Belotti

L’influence des conditionnements sociaux sur la formation du rôle féminin dans la petite enfance

#life quote#book quotes#Elena Gianini Belotti#john stuart mill#psychology#behaviorism#gender roles#social construct#girls#blue#boys#pink#social conditioning#gender conditioning#female subjection#empathy#training#feminism#raise boys to be feminist

1 note

·

View note

Text

[Sono stata anch'io bambina][Roberta Ortolano][Samanta Picciaiola]

Clicca qui per acquistare il libro

Titolo: Sono stata anch’io bambina. Dialoghi con Elena Gianini BelottiScritto da: Roberta Ortolano e Samanta PicciaiolaEdito da: tab edizioniAnno: 2023Pagine: 156ISBN: 9788892958234

Roberta Ortolano e Samanta Picciaiola, insegnanti femministe, ripercorrono insieme concetti e riflessioni che Elena Gianini Belotti ci ha lasciato in eredità, a un anno dalla sua…

View On WordPress

#2023#Dialoghi con Elena Gianini Belotti#Elena Gianini Belotti#gender#Giusi Marchetta#Italia#LGBT#LGBTQ#nonfiction#Roberta Ortolano#Saggi#Samanta Picciaiola#Sono stata anch&039;io bambina#tab edizioni

0 notes

Text

A proposito del monologo della Cortellesi, di cui in tanti non ha letto l'intero e - come fanno in tanti - e forse hanno solo sentito dire un paio di frasi magari anche riportate

«Le figure femminili delle favole appartengono a due categorie fondamentali – scriveva allora Belotti – le buone e inette e le malvagie. […] Non esiste, per quanta cura si ponga nel cercarla, una figura femminile intelligente, coraggiosa, attiva, leale». Perché le fiabe sono (come ricordava proprio Calvino, citato in modo assai strumentale in vari commenti critici) un catalogo dei destini disponibili in una specifica cultura per le donne e gli uomini e quindi non possono che riprodurre modelli e visioni del mondo che connotano tale cultura. E fiabe come Cenerentola e Biancaneve sono state elaborate in epoche caratterizzate da situazioni e contesti in cui i ruoli di donne e uomini erano fortemente asimmetrici. Pensiamo solo alla diffusa presenza di matrigne (cattive), che ci parla in realtà di un fenomeno sociale molto diffuso: le ricorrenti morti per parto delle donne e il fatto che gli uomini tendessero a risposarsi con ragazze più giovani, che potessero prendersi cura dei figli già presenti e sfornarne altri e che forse non erano così entusiaste di farlo.

Fiabe che in realtà sono poi state più volte modificate per adattarsi alle aspettative culturali dei tempi in cui venivano raccontate: le stesse trame dei film di Disney sono in realtà lontane anni luce dalle "versioni originali".

Elena Gianini Belotti “Dalla parte delle bambine”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

«Se ogni figlio fosse visto come un individuo unico, provvisto di potenzialità proprie e al quale offrire il massimo per aiutarlo a svilupparsi nella sua direzione, la questione del sesso perderebbe automaticamente importanza.»

Elena Gianini Belotti

Dalla parte delle bambine.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Elena Gianini Belotti, Dalla parte delle bambine, prefazione di Concita De Gregorio, Feltrinelli, nuova edizione 2023

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Dalla parte delle bambine

Dalla parte delle bambine

La tradizionale differenza di carattere tra maschio e femmina non è dovuta a fattori “innati”, bensì ai “condizionamenti culturali” che l’individuo subisce nel corso del suo sviluppo. Questa la tesi appoggiata da Elena Gianini Belotti e confermata dalla sua lunga esperienza educativa con genitori e bambini in età prescolare. Ma perché solo “dalla parte delle bambine”? Perché questa situazione è…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Quote

L'objectif de la séparation entre les sexes est atteint de mille manières, mais la première consiste à les considérer comme deux groupes distincts en les mettant souvent en rivalité entre eux et en accentuant les différences de comportement […]. On a aussi recours à des interventions qui visent à mettre les deux groupes, non seulement en position antagoniste, mais dans des attitudes de crainte et de méfiance réciproque, comme s'ils étaient ennemis et donc incapables de se rencontrer et de se comprendre. “Ne va pas jouer avec les garçons, tu sais bien qu'ils vont te faire du mal” […]. Les petits garçons qui voudraient jouer avec les petites filles sont découragés de façon encore plus efficace par la peur du ridicule, on leur fait comprendre que les jeux féminins sont dégradants pour eux : l'objectif est atteint, qui consiste à persuader les garçons que les petites filles sont des êtres inférieurs et méprisables, et à en persuader également les filles. A ce niveau, la séparation est déjà irrémédiable et bien peu d'enfants se risquent à franchir la barrière imposée ; ce n'est pas seulement la critique de l'adulte qui les en empêches, mais aussi celle des enfants de leur âge qui, ayant accepté cette séparation comme une loi, ont à cœur de s'y plier personnellement et de l'imposer aussi à tous les autres par conformisme.

Elena Gianini Belotti, Du côté des petites filles (1973), chap. 4 “Les institutions scolaires (Les enseignantes qui exercent la discrimination)”

#Elena Gianini Belotti#du côté des petites filles#féminisme#french stuff#readings#v#women to look up to

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Viene celebrata la superiorità dell'intuito femminile perché a chi domina fa molto comodo che i propri desideri siano capiti ancor prima di essere formulati, e soddisfatti da un essere condizionato a considerare i bisogni degli altri prima dei suoi e spesso contro i suoi.

Lo sviluppo femminile può essere definito una frustrazione permanente.

- Elena Gianini Belotti

416 notes

·

View notes

Note

ciao pizzetta, vorrei informarmi in modo molto più serio, hai consigli su autrici femministe?

- Odio gli uomini di Pauline Hermange

- Per farla finita con la famiglia. Dall’aborto alle parentele postumane di Angela Balzano

- Ripartire dal desiderio di Elisa cuter

- L’atlante delle donne di Joni Seager

- La rabbia ti fa bella di Soraya Chemaly

- Femminismo per il 99% un manifesto di Cinzia Arruzza

- Manuale per ragazze rivoluzionare: perché il femminismo ci rende felici (molto basico, forse per avvicinarti alla teoria femminista è perfetto, mio umile parere)

- Il secondo sesso di Simone de Beauvoir che devo finire anche io

- Libere tutte di Cecilia d’Elia

- Il femminismo è superato! Falso. di Paola Columba

- Questione di genere. Il femminismo e la sovversione dell’identità di Judith Butler

- Invisibili di Caroline Criado Perez

- Dalla parte delle bambine di Elena Gianini Belotti

- Fame di Roxane Gray

Ne avrei altri mille da scrivere

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

A noi donne cosiddette mature, è molto difficile uccidere l'adolescente che è dentro di noi.

Ci guardiamo allo specchio, poco, per la verità, e sappiamo che la faccia che vi scorgiamo non ha quasi niente a che vedere con quello che siamo dentro.

- Elena Gianini Belotti

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lo sviluppo femminile può essere definito una frustrazione permanente.

Elena Gianini Belotti - Dalla parte delle bambine

#Dalla parte delle bambine#libro un po’ vecchiotto ma incredibilmente interessante#sessismo#femminismo#quote

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Elena Gianini Belotti || Du côté des petites filles

source: abebooks

#elena gianini belotti#du côté des petites filles#what are little girls made of?#stereotypes#feminine stereotypes#exploitation#oppression#balance of power#book#gender politics#female subordination#Elena G. Belotti

0 notes

Text

Russian women, between Bolshevik feminism and Romance

Next to the homo sovieticus, communism created the mulier sovietica. In the 1920s, the Bolsheviks initiated a massive campaign of transformation of the role of women in Russian society. Lenin himself often treated gender issues, complaining in his speeches, the traditionalist mentality that looked at women as nothing more than a “domestic slave”. The blame, according to the father of the Revolution, was mainly due to the two main enemies of socialism: religion and capitalism. “Capitalism is the main source of slavery for women […] The religious marriages are still prevailing in the countryside. This is due to the influence of priests, an evil that is harder to fight than the old legislation” he wrote in his pamphlets. Lenin worked for a total and, for the standards of that time, unthinkable gender equality. “One of the hardest things in every country has always been to push women towards action. There can be no socialist revolution without women workers involved in it. Socialism only can save them from this status of ‘domestic slaves’”. No longer housewife thus, women became an active proletarka in politics. To this end, society was redesigned to eliminate the workload of the housework. Not eating any more at home, something that is an individualistic characteristic and also “a waste of time and energy”, Aleksandra Kollontai used to thunder disdainfully. Kollontai was a Bolshevik feminist and a close collaborator of Lenin. “We are organizing communal kitchens and canteens, laundries, cobblers, kindergartens, children’s homes and institutions of various types. In short, we are serious about carrying out the requirements of our program to move domestic and educational tasks from the family context to the social one. Women freed themselves from their old domestic slavery and dependence on their husbands. Any woman will be able to put her skills and inclinations at the service of society”. This system, which was more efficient at social level and in line with socialist principles, did work indeed.

For the Bolsheviks, women represented an opportunity not to be missed: make them emancipate not only meant to redeem a large part of the oppressed population, but also to use that enormous potential work force of which the country needed so much for technological and economic progress. Factory work represented a way out, for the Russian women, the liberation from conservative culture that wanted them cut off from the existing working and social lives, relegated to the stove and to the care of babies.

The Bolsheviks established a real women’s department, the Zhenotdel. The feminine power within the Party was part of a broader and more complex concept of feminism. If in the West, women were fighting for voting rights, sexual freedom and divorce, in Russia, figures such as Clara Zetkin had declared war on capitalism, which was considered the root of all evils and therefore also of the patriarchal culture. Zetkin, born in Germany, but died in exile in the Soviet Union, not far from Moscow, was one of the most aggressive communist fighting leaders for women’s self-determination. For Bolshevik feminists, women’s issues were tied with the class struggle. Claiming the right to vote, without the proletariat issues, was considered a limiting petty bourgeois aspiration by Zetkin. She complained about the excessive attention that new generations gave to sexual matters. She agreed in all respects with Lenin when he said: “This so-called ‘new sex life’ seems to me a mere extension of the good old bourgeois brothel”.

Like it or not, it was thanks to the Bolsheviks that Russia became one of the first nations to ensure genuine gender equality in society and at work. “We have the most advanced legislation in the world of women’s work” Lenin used to say; and he was right. This happened in the 1920s, in Russia, while in 1973, in Italy, Elena Gianini Belotti in her book “On the girls’ side” denounced the legacy of a patriarchal society unconsciously adopted in Italian schools. On the other hand, even in China women benefited the thrust of the egalitarian socialist principles. The advent of communism, as a matter of fact, managed to eradicate those costumes that were the legacy of a society considered medieval by Chinese Communists. The same happened in the countries of the socialist block in Eastern Europe. An Italian friend of mine once confided to me that during his first trip to Ceaucecu’s Romania, he was surprised to see that women were working as tram and trolley buses drivers. In Italy at that time it was a job for men only.

No need to wait for the advent of communism to notice prominent female figures in Russia. In Tsarist times, the Decembrists’ wives, women married to army officers who had rioted against Nicholas I, wrote a beautiful page of history. In December 1825 those men, fascinated by the ideal of equality of the French Revolution, attempted a revolt against the tsar to abolish serfdom and set a constitutional monarchy. The attempt did not go well: the troops loyal to tsar Nicholas I crushed the rebellion and he ordered to execute five of the responsible leaders and to send the remaining 120 men to forced labour to remote Siberia.

The Decembrists’ wives (a word that comes from the Russian dekabr “December”, the month in which the officers rebelled) distinguished themselves for bravery and tenacity. The Tsar ordered them to leave their husbands to their fate, otherwise they would have lost all their properties and privileges and they wouldn’t be allowed to go back to European Russia. Those women, however, defying Nicholas I’s threats, set off by stagecoach (the Trans-Siberian railway was not yet built) towards Siberia in order to reach their men. Their arrival brought a breath of civilization, a more open-minded and European customs in places that were considered no man’s lands and inhabited by hardy pioneers. The Decembrists’ wives convinced the guards to alleviate the living conditions of prisoners and provided food to their husbands who received only a meagre daily ration. They opened craft and commercial activities in the villages and they help the locals fight illiteracy and become more educated. They deserve credit for turning those poor muddy villages into habitable places.

Chita and Irkutsk, in eastern Siberia, are considered the Decembrists’ cities. It is here that were deported and it is also here they decided to remain living even after Alexander II granted them the remission of sentence. It is the fascinating story of these unfortunate heroes and their faithful consorts that drives me here, to Chita. This time I get along very smoothly: only 10 hours by train. The hotel I find is a short walk from the train station. The receptionist is a big woman with pale blond hair and speaks to me in Russian from the beginning to the end, convinced as she is that I understand every single word. She shows me the huge room, then gives me the keys and goes back to the reception desk to read the magazine from which I had turned her away. Although it is the middle of summer, I am the only customer at the hotel, which is furnished in a 1970s-style with linoleum floor covered with heavy Armenian carpets and rough wallpaper, yellowed by the years. The bathrooms are patched with different colour tiles and the soap is peach flavoured. I like this hotel, it looks like a retro decaying Soviet hotel. Chita is a quiet town, embellished by colourful, old buildings along Ulitsa Lenina covered with silvery spires. In the square, under the watchful gaze of the pink statue of Lenin positioned in front of the fountain, teenagers play splashing water to each other to relieve the summer heat. The golden onion-shaped domes of the cathedral reflect the Siberian sun.

In this city, there is the most comprehensive museum dedicated to the Decembrists. I decided to go and see. I walk along the desolate Decembrists Street, with its wooden houses built with round beams and decorated with bright embroidered windows, but I end up lost in a maze of a Brezvnian condominium, those sad crumbling concrete blocks where families still live. I’m about to give up when, hidden behind leafy trees, I saw a pretty wooden church with a green-greyish roof. It is Saint Michael’s Church, which houses the museum I was looking for. I step into the dark entrance and the caretaker, a white-haired woman in her sixties, looks up from the book she is reading, greets me, “Zdrasvuitye” and turn on the lights. I feel like she is opening the museum for me and, in a way, she did. I am the only visitor and the wide hall of the church is kept in the shadows and lit only when some few guests come. The lady is very friendly and starts speaking Russian to me. I explain that I’m italianka (Italian), so I can’t understand what she says, but she is not discouraged. “Ah, italianka” she comments and smiles at me showing bright, shiny gold teeth. She shows me around the museum explaining the Decembrists’ stories in Russian. And as I am italianka, the lady deduces that I also speak French so she starts showing me all that is written in French there, continuing to tell about the harsh living conditions of the exiles.

The Second World War was for Russian women, like those of Western Europe, a further leap forward: having men committed at the front, women had to become even more independent. “More than independent, Russian women are aggressive and full of themselves – says Eric, a Brazilian guy who has been living in Russia for two years, while we are sipping tea in one of the Ziferblats, (those tearooms where you can read, play games, socialize not paying for the consummation, but for the elapsed time) – they tend to flaunt a safety of themselves and look as flashy sometimes displaces men”. Many girls around here do not leave the house if not perfectly dressed and made up. “They wear high heels just to go to the grocery store”, Eric pointed out to me arguing that this trend is dictated by a syndrome of “catch-men” impatience to find a husband. Throughout my trip, I will find out that Eric’s opinion is not an isolated one, but the idea that most Western men have about Russian women.

After so much feminism in Russia, there is therefore a return to romance as “White Knight”. “We don’t want to be strong. “Having a man to take care of us and who makes us feel protected, this is what we want – Aleksandra replies, a Muscovite girl with whom I met – when I tell her that I think the history of their country helped Russian women grow stronger – we greatly appreciate the attentions of a gentleman”. In Russia, men are often gallant with women, showing “an old-fashioned style” sensitivity, now vanished or lost in Western Europe. Giving women their seats on the bus, helping passers-by with luggage at the stations, giving way, opening the car door as a sign of courtesy are still examples of gallantry in use around here.

According to some young women with whom I spoke, however, romance often collides with reality: it would seem that Russian men tend to be absent in the family. This makes the new generations often grow without the paternal figure. “Who sets the example? Who teaches children how to become men?”, Complains my friend Maria. In traditional thirteenth century Russia, relationships between princes were concluded orally, without the need to draw up any contract. They only need their word to define what some have called “the power of the steppe”. In Europe, however, the rich body of codes and written laws inherited from the ancient Romans created a culture of written contracts to be concluded with signatures. “Verba volant, scripta manet”, said Caio Titus, to emphasize that only written documents could be a guarantee of and for mutual trust. Although after the advent of the Soviets in Russia things have changed, for men the power of the word has remained deeply rooted in the mentality. However, it now seems that this culture tends to slowly be disappearing.

Russia, Coast-to-Coast From the Baltic Sea to the Pacific Ocean: Russia viewed from the train (part 8) Russian women, between Bolshevik feminism and Romance Next to the homo sovieticus, communism created the mulier sovietica.

0 notes

Text

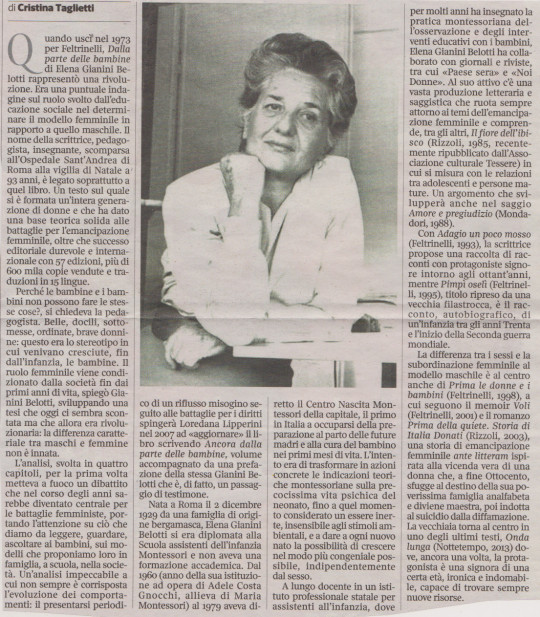

Con le bambine e con le donne. Addio a ELENA GIANINI BELOTTI (1929-2022), articolo di Cristina Taglietti in Corriere della Sera 27 dicembre 2022

Con le bambine e con le donne. Addio a ELENA GIANINI BELOTTI (1929-2022), articolo di Cristina Taglietti in Corriere della Sera 27 dicembre 2022

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Quote

[L]'opinion courante veut que les filles soient plus difficiles à éduquer. Pourquoi ?

Il est beaucoup plus difficile et pénible de contenir une énergie souvent impérieuse en prétendant qu'elle se replie sur elle-même, alors qu'elle ne tarde pas à s'atrophier lentement, que de lui laisser libre cours et même de la stimuler en vue de réalisations concrètes. Il est plus simple de pousser un individu vers son développement propre que de réprimer la pulsion de réalisation de soi présente chez tous les individus, toute considération de sexe mise à part.

La fille, inhibé dans son propre développement, est contrainte d'organiser des mécanismes d'autodéfense pour ne pas succomber, surtout dans les cas où sont énergie particulièrement vive a entraîné des répressions massives ; elle manifeste des traits de caractères qui ne sont pas du tout, comme on le pense, l'apanage du sexe féminins, mais sont simplement le produit de la castration psychologique opérée à ses dépends.

Elena Gianini Belotti, Du côté des petites filles (1973), chap. 1 “L’attente de l’enfant (C’est le garçon le préféré)”

5 notes

·

View notes