#Fr. Henri de Lubac

Text

“It is not a question of adapting Christianity to men, but of adapting men to Christ.”

- Fr. Henri de Lubac, Paradoxes of Faith

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Image by Chris Powers

Christ has two natures: what does that have to do with me? If He bears the name of Christ, magnificent and consoling as it is, it is because of the ministry and the task He took upon Himself; that is what gives Him the Name. That He is by nature both man and God, this is something for Himself. But that He consecrated His ministry and poured out His love to become my Savior and my Redeemer, that is where I find my consolation and my good.

- Martin Luther

Christ has two natures: what is that to me? — But the substantial reparation of humanity lies in that very fact. But this joining of the divine and human touches what is most profound and most inalienable in me, my very nature. Christ has two natures: what is that to me? — But every living intelligence is directly, personally, profoundly involved in this central fact of the history of being, which brings divinization of creatures. At the moment that affects the very depths of being itself, it affects the depths of my own being.

- Fr. Pierre Rousselot, S.J., in a lecture given on the passage above in 1909-1910.

On occasion [Luther and Melanchthon] freely express themselves in a paradoxical, antithetical way which one should not always take literally. Still, their language does indicate a tendency. Neither Luther nor Melanchthon —nor Calvin, for that matter— "pauses to analyze the being of the eternal Son of God made man, i.e., to describe the hypostatic union; rather, they proceed directly to the explanation of his redemptive work"; their entire perspective remains soteriological. With Luther most particularly, his customary language manifests a thought which is "less concerned about knowing Christ's inner mystery than about hearing his promises and the sovereign call of his voice" — and even, we must admit, "a certain scorn for all intellectual dogmatic statements, which he considers as only a side issue in true religious life." [...] We may, however, observe that this consequence is logical enough: if one begins with an experience in which the person of Christ tends to disappear behind his gifts, if the Incarnation is looked upon as a simple prelude to the redemption, it is quite natural to find oneself being carried away to a more and more subjective theology[, ...] an anthropocentric withdrawal.

- Henri de Lubac (The Christian Faith: An Essay on the Structure of the Apostles' Creed, pages 99-100, 101, 103), trans. Richard Arnandez, F.S.C. Bolded emphases added

#Christianity#Lutheranism#Catholicism#Martin Luther#Jesus Christ#Incarnation#Cosmic Man#theosis#Henri de Lubac#redemption#salvation#Christopher Powers

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Back to research for my book on the impact of military service on future theological writings. The ‘Twentieth-Century Catholic Theologians’ (2007) by Fergus Kerr, OP is worth acquiring for his Chapter 12 ‘Before Vatican II’ alone. While written in 2007 it reflects the divisions amongst Catholics on Twitter in 2022. Fr. Kerr, OP also covers in Chapter 1 ‘Before Vatican II’, then covers 10 theologians in surmounting neo-scholasticism. ‘Neo-scholasticism was the attempt to solve the modern crisis of theology by picking up the thread of the high scholastic tradition of medieval times. The aim was to establish a timeless, unified theology that would provide a norm for the universal church.’ (Walter Kasper, 1987) Kerr also shows how power struggles within the church, & events in the wider world: the 1st WW, the rise of fascism & Soviet communism, the 2nd WW, & the cold war cannot be separated from the fate of the 10 theologians he explores. - Marie-Dominique Chenu, OP - Yves Congar, OP (Marie-Joseph Congar, name eventually dropped) [in my book] - Edward Schillebeeckx, OP - Henri de Lubac, SJ [in my book] - Karl Rahner, SJ - Bernard Lonergan, SJ - Hans Urs von Balthasar (a former Jesuit, he sought to return to the Jesuits, but negotiations failed: they were not willing to take responsibility for the Johannesgemeinschaft) [Kerr notes von Balthasar as the most discussed Catholic theologian at the present time. And, as the greatest Catholic theologian of the century.] - Hans Kung - Karol Wojtyla (learned his concept of ‘nuptiality’) [in my book] - Joseph Ratzinger [in my book] - In the Appendix, he provides ‘The Anti-modernist Oath’: signed by Pope Pius X on 1 September 1910, abrogated only in 1967. - I look forward to reading Kerr’s ‘After Aquinas: Visions of Thomism’ (2002). https://www.instagram.com/p/CkfwZc9rHC7/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Catholic Physics - Reflections of a Catholic Scientist - Part 70

Last Days and the Resurrection the Dead III: The Omega Point of Teilhard de Chardin

Story with image:

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/catholic-physics-reflections-scientist-part-70-harold-baines/?published=t

The Vision of Teilhard de Chardin from Wikimedia Commons (Caption for linked image)

“The great cosmic attributes of Christ, those which (particularly in St John and St Paul) accord him a universal and final primacy over creation, these attributes... only assume their full dimension in the setting of an evolution... that is both spiritual and convergent.[emphasis added]” Teilhard de Chardin, Catholicism and Science.

“The Church, the reflectively christified portion of the world, the Church, the principal focus of interhuman affinities through super-charity, the Church, the central axis of universal convergence and the precise point of contact between the universe and Omega Point.” Teilhard de Chardin, My Fundamental Vision

INTRODUCTION

This is the third in a series on unconventional propositions about last days and the resurrection of the dead. The first was on that of the Russian mathematician, Andrej Grib, dealing with quantum logic; the second on that of the American physicist, Frank Tipler, dealing with his physics derived Omega Point; this, the third, on the Omega Point as a goal in evolution, devised by the French Jesuit paleontologist, Teilhard de Chardin.

With respect to the first two -- Grib and Tipler -- I want to emphasize that although I find parts of these propositions appealing, I disagree with what they say about last days and the resurrection of the dead. They are not consistent with Catholic Teaching. Nevertheless, we can sometimes learn more about the truth by showing what is false, and it was in that spirit that I posted those two articles: to highlight what Catholic teaching tells us about last days and the resurrection of the dead.

Teilhard de Chardin's thesis is one more difficult to summarize and encapsulate in a short post. He has fan clubs pro and con; there have been books and articles (including those by Popes) extolling his work, and those by emininent theologians consigning it to an ash-heap. I will try to summarize the essential points and to point the reader to online sources (for and against) that delve more deeply.

THE THESIS OF TEILHARD DE CHARDIN

Teilhard de Chardin participated in an important discovery in the evolutionary descent of humans, the discovery of Peking Man. His training as a Jesuit and a scientist formed his belief that both the Catholic faith and science were true and good, and that one need not forsake one to follow the other. As N.M. Wildiers put it,

"In order fully to understand a writer... [we must] form as clear a picture as we can of the problem to which the teaching is presumed to supply a solution... the central problem with which Teilhard was concerned, the problem which is the core of his theological thought,... was without doubt what is now known as secularization." N.M. Wildiers, Foreword, Christianity and Evolution

The implication here is that secularization, the loss of religious values, comes about because science is separated from religion. Accordingly, de Chardin's project was to bring them together again.

The diagram at the top of the post illustrates Teilhard de Chardin's scheme for uniting science and Catholic teaching. The scheme operates under the following principle:

"...creation is not a periodic intrusion of the First Cause: it is an act co-extensive with the whole duration of the universe. God has been creating ever since the beginning of time, and, seen from within, his creation (even his initial creation?) takes the form of a transformation. Participated being is not introduced in batches which are differentiated later...God is continually breathing new being into us.[emphasis in original]" Teilhard de Chardin, Christianity and Evolution, p. 2

Thus there are stages in this continuous development, in the evolution of the cosmos, as listed in the figure above: matter-> life-> thought --> spirit, or atoms --> cells --> man --> Omega Point (Christ). At the Omega point all will coalesce and, as near as I understand de Chardin, there will be a super consciousness into which individuals are subsumed.

The Christ of Teilhard's Omega Point is more than Christ the Word, who as God created all things, and Jesus, the man who suffered and died to save us. He is "Christ-the-Evolver".

"[He is identified] not with the ordinating principle of the stable Greek kosmos [the Logos], but with the neo-Logos of modern philosophy, the evolutive principle of a universe in movement." op. cit, p. 181.

Finally, de Chardin would combine the three mysteries of Christology -- Creation, Incarnation, Redemption -- into a fourth:

"The three mysteries become in reality no more, for the new Christology,... they are aspects of a fourth mystery, which alone... is absolutely justifiable and valid... it is the mystery of the creative union of the world in God or Pleromization." op.cit., p. 183

MY TAKE

In the above I have not commented on de Chardin's views on resurrection of the dead; as near as I can tell from his works and commentaries on them he supposes that we are immortal (as a soul) and will be subsumed into the Omega Point at the end. This is not the view given in Catholic teaching: both body and soul will be resurrected and we will be resurrected as individuals, not as components of a super-being.

With respect to other parts of de Chardin's Christology and theology, I can only say it is like the curate's egg: there are some excellent parts and parts which are BAAD! I'll leave it to the reader (after he/she goes through the references linked below) to decide which is which.

PROS AND CONS

Early in his career de Chardin ran into problems with Church authorities because of his novel views on evolution and the Dogma of Original Sin. I won't discuss this matter here (it's worth at least two posts) but link to the following reference: Evolution and Original Sin: the Problem of Evil (written by Jesuit priests and seminarians).

I'll list the links below for Teilhard fans and anti-fans:

PROS

Teilhard de Chardin, World Public Library

Orthodoxy of Teilhard de Chardin, Part V.

Teilhard de Chardin and Trans-humanism

Will the Vatican let Teilhard de Chardin save the Church?

In the above there are quotes from Pope-emeritus Benedict XVI, writing as Joseph Ratzinger, extolling de Chardin's new views on Christology. In addition, prominent theologians, such as Henri, Cardinal du Lubac, have praised his work.

CONS

Challenging the Rehabilitation of Teilhard de Chardin

Critique of Fr. Teilhard de Chardin by Dr. Deitrich von Hildebrand

A Review of "The Phenomenon of Man" by Sir Peter Medawar (this review criticizes de Chardin's science, not his theology.)

From a series of articles written by: Bob Kurland - a Catholic Scientist

1 note

·

View note

Text

Fifth Lenten Sermon of Fr. Cantalamessa to papal household: Full text

(Vatican Radio) The Preacher of the Papal Household, Fr. Raniero Cantalamessa, O.F.M. Cap., gave his fifth Lenten Sermon to Pope Francis on Friday morning in the Redemptoris Mater Chapel.

The theme of the Lenten meditations is: “No one can say, ‘Jesus is Lord’, except by the Holy Spirit” (1 Corinthians 12:3). This fifth iteration carried the title: 'The Righteousness of God has been Manifested: The Fifth Centenary of the Protestant Reformation, an Occasion of Grace and Reconciliation for the Whole Church.'

Please find below an English translation of the Sermon by Marsha Daigle Williamson:

Fifth Lenten Sermon 2017

“THE RIGHTEOUSNESS OF GOD HAS BEEN MANIFESTED”: The Fifth Centenary of the Protestant Reformation, an Occasion of Grace and Reconciliation for the Whole Church

1. The Origins of the Protestant Reformation

The Holy Spirit, who, as we saw in the preceding meditations, leads us into the fullness of truth about the person of Christ and his paschal mystery, also enlightens us on a crucial aspect of our faith in Christ, that is, on how we obtain in the Church today the salvation Christ accomplished for us. In other words, the Holy Spirit enlightens us on the important question of justification by faith for sinners. I believe that trying to shed light on history and on the current state of that discussion is the most useful way to make the anniversary of the Fifth Centenary of the Protestant Reformation an occasion of grace and reconciliation for the whole Church.

We cannot dispense with rereading the whole passage from the Letter to the Romans on which that discussion is centered. It says,

But now the righteousness of God has been manifested apart from law, although the law and the prophets bear witness to it, the righteousness of God through faith in Jesus Christ for all who believe. For there is no distinction; since all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God, they are justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption which is in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as an expiation by his blood, to be received by faith. This was to show God’s righteousness, because in his divine forbearance he had passed over former sins; it was to prove at the present time that he himself is righteous and that he justifies him who has faith in Jesus. Then what becomes of our boasting? It is excluded. On what principle? On the principle of works? No, but on the principle of faith. For we hold that a man is justified by faith apart from works of law. (Rom 3:21-28)

How could it have happened that such a comforting and clear message became the bone of contention at the heart of western Christianity, splitting the Church and Europe into two different religious continents? Even today, for the average believer in certain countries in Northern Europe, that doctrine constitutes the dividing line between Catholicism and Protestantism. I myself have had faithful Lutheran lay people ask me, “Do you believe in justification by faith?” as the condition for them to hear what I had to say. This doctrine is defined by those who began the Reformation themselves as “the article by which the Church stands or falls” (articulus stantis et cadentis Ecclesiae).

We need to go back to Martin Luther’s famous “tower experience” that took place in 1511 or 1512. (It is referred to this way because it is thought to have occurred in a cell at the Augustinian monastery in Wittenberg called “the Tower”). Luther was in torment, almost to the point of desperation and resentment toward God, because all his religious and penitential observances did not succeed in making him feel accepted by God and at peace with him. It was here that suddenly Paul’s word in Romans 1:17 flashed through his mind: “The just shall live by faith.” It was a liberating experience. Recounting this experience himself when he was close to death, he wrote, “When I discovered this, I felt I was reborn, and it seemed that the doors of paradise opened up for me.”[1]

Some Lutheran historians rightly go back to this moment some years before 1517 as the real beginning of the Reformation. What transformed this inner experience into a real religious chain reaction was the issue of indulgences, which made Luther decide to nail his famous 95 theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg on October 31, 1517. It is important to note the historical succession of these facts. It tells us that the thesis of justification by faith and not by works was not the result of a polemic with the Church of his time but its cause. It was a genuine illumination from above, an “experience,” “Erlebnis,” as he himself described it.

A question immediately arises: how do we explain the earthquake that was caused by the position Luther took? What was there about it that was so revolutionary? St. Augustine had given the same explanation for the expression “righteousness of God” many centuries earlier. “The righteousness of God [justitia Dei],” he wrote, “is the righteousness by which, through his grace, we become justified, exactly the way that the salvation of God [salus Dei] (Ps 3:9) is the salvation by which God saves us.”[2]

St. Gregory the Great had said, “We do not attain faith from virtue but virtue from faith.”[3] And St Bernard had said, “What I cannot obtain on my own, I confidently appropriate (usurpo!) from the pierced side of the Lord because he is full of mercy. . . . And what about my righteousness? O Lord, I will remember only your righteousness. In fact it is also mine because you became God’s justification for me (see 1 Cor 1:30).”[4] St. Thomas Aquinas went even further. Commenting on the Pauline saying that “the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life” (see 2 Cor 3:6), he writes that the “letter” also includes the moral precepts of the gospel, so “even the letter of the gospel would kill if the grace of faith that heals were not added to it.”[5]

The Council of Trent, convened in response to the Reformation, did not have any difficulty in reaffirming the primacy of faith and grace, while still maintaining (as would the branch of the Reformation that followed John Calvin) the necessity of works and the observance of the laws in the context of the whole process of salvation, according to the Pauline formula of “faith working through love” (“fides quae per caritatem operatur”) (Gal 5:6).[6] This explains how, in the context of the new climate of ecumenical dialogue, it was possible for the Catholic Church and the Lutheran World Federation to arrive at a joint declaration on justification by grace through faith that was signed on October 31, 1999, which acknowledges a fundamental, if not yet total, agreement on that doctrine.

So was the Protestant Reformation a case of “much ado about nothing?” The result of a misunderstanding? We need to answer with a firm “No”! It is true that the magisterium of the Church had never reversed any decisions made by preceding councils (especially against the Pelagians); it had never forgotten what Augustine, Gregory, Bernard, and Thomas Aquinas had written. Human revolutions do not break out, however, because of ideas or abstract theories but because of concrete historical situations, and unfortunately for a long time the praxis of the Church was not truly reflecting its official doctrine. Church life, catechesis, Christian piety, spiritual direction, not to mention popular preaching—all these things seemed to affirm just the opposite, that what really matters is in fact works, human effort. In addition, “good works” were not generally understood to mean the works listed by Jesus in Matthew 25, without which, he says, we cannot enter the kingdom of heaven. Instead, “good works” meant pilgrimages, votive candles, novenas, and donations to the Church, and as compensation for doing these things, indulgences.

The phenomenon had deep roots common to all of Christianity and not just Latin Christianity. After Christianity became the state religion, faith was something that was absorbed instinctively through the family, school, and society. It was not as important to emphasize the moment in which faith was born and a person’s decision to become a believer as it was to emphasize the practical requirements of the faith, in other words, morals and behavior.

One revealing sign of this shift of focus is noted by Henri de Lubac in his Medieval Exegesis: The Four Senses of Scripture. In its most ancient phase, the sequence of the four senses was the literal historical sense, the christological or faith sense, the moral sense, and the eschatological sense.[7] However, that sequence was increaingly substituted by a different one in which the moral sense came before the christological or the faith sense. “What to do” came before “what to believe”; duty came first before gift. In spiritual life, people thought, first comes the path of purification then that of illumination and union.[8] Without realizing it, people ended up saying exactly the opposite of what Gregory the Great had written when he said, “We do not attain faith from virtue but virtue from faith.”

2. The Doctrine of Justification by Faith after Luther

After Luther and very soon after the two other great reformers, Calvin and Ulrich Zwigli, the doctrine of the free gift of justification by faith resulted, for those who lived by it, in an unquestionable improvement in the quality of Christian life, thanks to the circulation of the word of God in the vernacular, to numerous inspired hymns and songs, and to written aids made accessible to people by the recent invention of the printing press and distribution of printed materials.

On the external front, the thesis of justification only by faith became the dividing line between Catholicism and Protestantism. Very soon (and in part with Luther himself) this opposition broadened out to become an opposition between Christianity and Judaism as well, with Catholics representing, according to some, the continuation of Jewish legalism and ritualism, and Protestants representing the Christian innovation.

Anti-Catholic polemic was joined to anti-Jewish polemic that, for other reasons, was no less present in the Catholic world. According to this perspective, Christianity was formed in opposition to—and was not derived from—Judaism. Starting with Ferdinand Christian Baur (1792-1860), the theory of two souls in early Christianity increasingly gained ground: Petrine Christianity, as expressed in the so-called “proto-catholicism “ (Frühkatholizismus), and Pauline Christianity that finds its more complete expression in Protestantism.

This belief led to distancing the Christian religion as far as possible from Judaism. People would try to explain the doctrines and Christian mysteries (including the title Kyrios, Lord, and the divine worship owed to Jesus) as the result of contact with Hellenism. The criterion used to judge the authenticity of a saying or a fact from the gospel was how different it was from what characterized the Jewish world of that time. Even if that approach was not the main reason for the tragic anti-Semitism that followed, it is certain that, together with the accusation of deicide, it encouraged anti-Semitism by giving it a tacit religious covering.

Beginning in the 1970s, there was a radical reversal in this area of biblical studies. It is necessary to say something about it to clarify the current state of the Pauline and Lutheran doctrine of the free gift of justification through faith in Christ. The nature and the aim of my talk exempt me from citing the names of the modern writers engaged in this debate. Whoever is versed in this subject will not have difficulty identifying the authors of the theories alluded to here to, but for others, I think, it is not the names but the ideas that are of interest.

This reversal involves the so-called “third quest of the historical Jesus.” (It is called “third” after the liberal quest of the 1800s and then that of Rudolf Bultmann and his followers in the 1900s). This new perspective recognizes Judaism as the true matrix within which Christianity was formed, debunking the myth of the irreducible otherness of Christianity with respect to Judaism. The criterion used to assess the major or minor probability that a saying or fact about Jesus’ life is authentic is its compatibility with the Judaism of his time—not its incompatibility, as people at one time thought.

Certain advantages of this new approach are obvious. The continuity of revelation is recovered. Jesus is situated within the Jewish world in the line of biblical prophets. It also does more justice to the Judaism of Jesus’ time, demonstrating its richness and variety. The problem is that this approach went too far so that this gain was transformed into a loss. In many representatives of this third quest, Jesus ends up dissolving into the Jewish world completely, without any longer being distinct except through a few particular interpretations of the Torah. He is reduced to being one of the Hebrew prophets, an “itinerant charismatic,” “a Mediterranean Jewish peasant,” as someone has written. The continuity with Judaism has been recovered, but at the expense of the newness of the New Testament. The new historical quest has produced studies on a whole different level (for example, those of James D. G. Dunn, my favorite New Testament scholar), but what I have sketched out is the version that is most widely circulated on the popular level and has influenced public opinion.

The person who shed light on the misleading character of this approach for the purposes of serious dialogue between Judaism and Christianity was precisely a Jew, the American rabbi, Jacob Neusner.[9] Whoever has read Benedict XVI’s book on Jesus of Nazareth is already familiar with much of the thinking of this rabbi with whom he dialogues in one of the most fascinating chapters of his book. Jesus cannot be considered a Jew like other Jews, Neusner explains, given that he puts himself above Moses and proclaims that he is “Lord also of the Sabbath.”

But it is especially in regard to St. Paul that the “new perspective” demonstrates its inadequacy. According to one of its most famous representatives, the religion of works, against which the Apostle rails with such vehemence in his letters, does not exist in real life. Judaism, even in the time of Jesus, is a “covenantal nomism,” that is, a religion based on the free initiative of God and his love; the observance of his laws is the consequence of a relationship with God, not its cause. The law serves to help people remain in the covenant rather than to enter it. The Jewish religion continues to be that of the patriarchs and prophets, and its center is hesed, grace and divine benevolence.

Scholars then have to look for possible targets of Paul’s polemic: not the “Jews” but the “Jewish-Christians,” or a kind of “Zealot” Judaism that feels itself threatened by the pagan world around it and reacts in the manner of the Maccabees—in brief, the Judaism of Paul prior to his conversion that led him to persecute Hellenistic believers like Stephen. But these explanations appear immediately unsustainable and result in making the apostle’s thinking incomprehensible and contradictory. In the preceding part of his letter, the apostle formulates a indictment as universal as humanity itself: “There is no distinction; . . . all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Rom 3: 22-23). Three times in the first three chapters of this letter he returns to the wording “Jews and Greeks alike.” How can anyone think that to such a universal evil a remedy corresponds which is aimed at a very limited group of believers?

3. Justification by Faith: A Doctrine of Paul or of Jesus?

The difficulty comes, in my opinion, from the fact that the exegesis of Paul is carried on at times as if the doctrine began with him and as if Jesus had said nothing on this matter. The doctrine of the free gift of justification by faith is not Paul’s invention but is the central message of the gospel of Christ, whether it was made known to Paul by a direct revelation from the Risen One or by the “tradition” that he says he received, which was certainly not limited to a few words about the kerygma (see 1 Cor 15:3). If this were not the case, then those who say that Paul, not Jesus, is the real founder of Christianity would be correct.

However, the core of this doctrine is already found in the word “gospel,” “good news,” that Paul certainly did not invent out of thin air. At the beginning of his ministry Jesus went around proclaiming, “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand; repent, and believe in the gospel” (Mk 1:15). How could this proclamation be called “good news” if it were only an intimidating call to change one’s life? What Christ includes in the expression “kingdom of God”—that is, the salvific initiative by God, his offer of salvation to all humanity—St. Paul calls the “righteousness of God,” but it refers to the same fundamental reality. “The kingdom of God” and “the righteousness of God” are coupled together by Jesus himself when he says, “Seek first his kingdom and his righteousness” (Mt 6:33).

When Jesus said, “repent, and believe the gospel,” he was thus already teaching justification by faith. Before him, “to repent” always meant “to turn back,” as indicated by the Hebrew word shub; it meant to turn back, through a renewed observance of the law, to the covenant that had been broken. “To repent,” consequently, had a meaning that was mainly ascetic, moral, and penitential, and it was implemented by changing one’s behavior. Repentance was seen as a condition for salvation; it meant “repent and you will be saved; repent and salvation will come to you.” This was the meaning of “repent” up to this point, including on the lips of John the Baptist.

When Jesus speaks of repentance, metanoia, its moral meaning moves into second place (at least at the beginning of his preaching) with respect to a new, previously unknown meaning. Repenting no longer means turning back to the covenant and the observance of the law. It means instead taking a leap forward, entering into a new covenant, seizing this kingdom that has appeared, and entering into it. And entering it by faith. “Repent and believe” does not point to two different successive steps but to the same action: repent, that is, believe; repent by believing! Repenting does not signify “mending one’s ways” so much as “perceiving” something new and thinking in a new way. The humanist Lorenzo Valla (1405-1457), in his Adnotations on the New Testament, had already highlighted this new meaning of the word metanoia in Mark’s text.

Innumerable sayings from the gospel, among the ones that most certainly go back to Jesus, confirm this interpretation. One is Jesus’ insistence on the necessity of becoming like children to enter the kingdom of heaven. A characteristic of children is that they have nothing to give and can only receive. They do not ask anything from their parents because they have earned it but simply because they know they are loved. They accept what is freely given.

The Pauline polemic against the claim to be saved by one’s own works also does not begin with him. We would need to exclude an endless number of texts to remove all the polemic references in the gospel to a number of “scribes, Pharisees, and doctors of the law.” We cannot fail to recognize in the parable of the Pharisee and the tax-collector in the temple the two types of religiosity that St. Paul later contrasts: one man trusts in his own religious performance and the other trusts in the mercy of God and returns home “justified” (Lk 18:14).

It is not a temptation present only in one particular religion, but in every religion, including of course Christianity. (The Evangelists didn’t relate the sayings of Jesus to correct the Pharisees, but to warn the Christians!) If Paul takes aim at Judaism, it is because that is the religious context in which he and those to whom he is speaking live, but it involves a religious rather than an ethnic category. Jews, in this context, are those who, unlike the pagans, are in possession of revelation; they know God’s will and, emboldened by this fact, they feel themselves secure with God and can judge the rest of humanity. One indication that Paul was designating a religious category is that Origen was already saying in the third century that the target of the apostle’s words are now the “heads of the Church: bishops, presbyters, and deacons,” that is, the guides, the teachers of the people.[10]

The difficulty in reconciling the picture that Paul gives us of the Jewish religion and what we know about it from other sources is based on a fundamental error in methodology. Jesus and Paul are dealing with life as people lived it, with the heart; scholars deal instead with books and written testimonies. Oral and written statements tell us what people know they should be or would like to be, but not necessarily what they are. No one should be surprised to find in the Scripture and rabbinical sources of the time moving and sincere affirmations about grace, mercy, and the prevenient initiative of God. But it is one thing to say what Scripture says and leaders teach and another thing to say what is in people’s hearts and what governs their actions.

What happened at the time of the Protestant Reformation helps us to understand this situation during the time of Jesus and Paul. At the time of the Reformation, if one looks at the doctrine taught in the schools of theology, at ancient definitions that were never disputed, at Augustine’s writings that were held in great honor, or even only at the Imitation of Christ that was daily reading for pious souls, one will find there the magnificent doctrine of grace and will not understand whom Luther was fighting against. But if one looks at what was going on in real life in the Church, the result, as we have seen, is quite different.

4. How to Preach Justification by Faith Today

What can we conclude from this bird’s-eye view of the five centuries since the beginning of the Protestant Reformation? It is indeed vital that the centenary of the Reformation not be wasted, that it not remain a prisoner of the past and try to determine rights and wrongs, even if that is done in a more irenic tone than in the past. We need instead to take a leap forward, the way a river that finds itself blocked resumes its course at a higher level.

The situation has changed since then. The issues that brought about the separation between the Church of Rome and the Reformation were above all indulgences and how sinners are justified. But can we say that these are the problems on which people’s faith stands or falls today? I remember Cardinal Kasper on one occasion making this observation: For Luther the number one existential problem was how to overcome the sense of guilt and find a gracious God; today the problem is rather the opposite: how to restore to human beings a genuine sense of sin that they have completely lost.

This does not mean ignoring the enrichment brought by the Reformation and wanting to return to the situation before it. It means rather allowing all of Christianity to benefit from its many important achievements once they are freed from certain distortions and excesses due to the overheated climate of the moment and the need to correct major abuses.

Among the negative aspects resulting from the centuries-old emphasis on the issue of the justification of sinners, it seems to me one is having made western Christianity be a gloomy proclamation, completely focused on sin, that the secular culture ended up resisting and rejecting. The most important thing is not what Jesus, by his death, has removed from human beings—sin—but what he has given to them, that is, his Holy Spirit. Many exegetes today consider the third chapter of the letter to the Romans on justification by faith to be inseparable from the eighth chapter on the gift of the Spirit and to be one piece with it.

The free gift of justification through faith in Christ should be preached today by the whole Church and with more vigor than ever. Not, however, in contrast to the “works” the New Testament speaks of but in contrast to the claim of post-modern people of being able to save themselves with their science and technology or with an improvised, comforting spirituality. These are the “works” that modern human beings rely on. I am convinced that if Luther came back to life, this would be the way that he too would preach justification by faith today.

There is another thing that we all—Lutherans and Catholics—should learn from the man who initiated the Reformation. As we saw, for Luther the free gift of justification by faith was above all a lived experience and only later something about which to theorize. After him justification though faith became increasingly a theological thesis to defend or to oppose and less and less a personal, liberating experience to be lived out in one’s intimate relationship with God. The joint declaration of 1999 very appropriately points out that the consensus reached by Catholics and Lutherans on the fundamental truths of the doctrine of justification must take effect and be confirmed not just in the teaching of the Church but in people’s lives as well (no. 43).

We must never lose sight of the main point of the Pauline message. What the apostle wishes to affirm above all in Romans 3 is not that we are justified by faith but that we are justified by faith in Christ; we are not so much justified by grace as we are justified by the grace of Christ. Christ is the heart of the message, more so than grace and faith. Today he himself is the article by which the Church stands or falls: a person, not a doctrine.

We ought to rejoice because this is what is happening in the Church and to a greater extent than commonly realized. In recent months I was able to attend two conferences: one in Switzerland organized by Protestants with the participation of Catholics, and the other in Germany organized by Catholics with the participation of Protestants. The latter conference, which took place in Augsburg this past January, seemed to me truly to be a sign of the times. There were 6,000 Catholics and 2,000 Lutherans, the majority of whom were young, who had come from all over Germany. Its title was “Holy Fascination.” What fascinated that crowd was Jesus of Nazareth, made present and almost tangible by the Holy Spirit. Behind this effort was a community of lay people and a house of prayer (Gebetshaus), which has been active for years and is in full communion with the local Catholic church.

It was not an easy ecumenism. There was a very Catholic Mass with lots of incense celebrated once by me and once by the auxiliary bishop of Augsburg; on another day, the Lord’s Supper was celebrated by a Lutheran pastor with full respect for each other’s liturgies. Worship, teachings, music: it was an atmosphere that only young people today are able to create and that could serve as a model for some special event during World Youth Day.

I once asked those in charge if they wanted me to speak about Christian unity. They answered, “No. We prefer to live that unity instead of talking about it.” They were right. These are signs of the direction in which the Spirit—and with him Pope Francis—invite us to go.

_______________________________

Translated from Italian by Marsha Daigle Williamson

[1] Martin Luther, “Preface to his Latin Works,” Weimar ed., vol. 54, p. 186.

[2] Augustine, On the Spirit and the Letter, 32, 56 (PL 44, 237).

[3] Gregory the Great, Homilies on Ezekiel, 2, 7 (PL 76, 1018).

[4] Bernard of Clairvaux, Sermons on the “Song of Songs,” 61, 4-5 (PL 183, 1072).

[5] Thomas Aquinas, Summa theologiae, 1-IIae, q. 106, a.2.

[6] Council of Trent, “Decretum de iustificatione,” 7, in Denziger and Schoenmetzer, Enchridion Symbolorum, ed. 34, n. 1531.

[7] The classical couplet that sets forth this sequence is “Littera gesta docet, quid credas allegoria. / Moralis quid agas; quo tendas anagogia”: “The literal sense proclaims the events, the allegorical sense what you should believe. / The moral sense what you should do, the anagogical sense where you are going.”

[8] See Henri de Lubac, Histoire de l’exégèse médiéval. Les quatre sens de l’Écriture (Paris, Aubier,1959), vol. 1, 1, pp. 139-157.

[9] Jacob Neusner, A Rabbi Talks with Jesus (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000).

[10] Origen, Commentary on the “Letter to the Romans,” 2, 2 (PG 14, 873).

(from Vatican Radio)

from News.va http://ift.tt/2nRJp1W

via IFTTT

from Blogger http://ift.tt/2oI50OK

0 notes

Text

“Nothing remains intact without effort. Repetition of formulas does not assure the transmission of thought. It is not safe to entrust a doctrinal treasure to the passivity of memory. Intelligence must play a part in its conservation, rediscovering it, so to speak, in the process.”

- Fr. Henri de Lubac S.J., Paradoxes of Faith

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

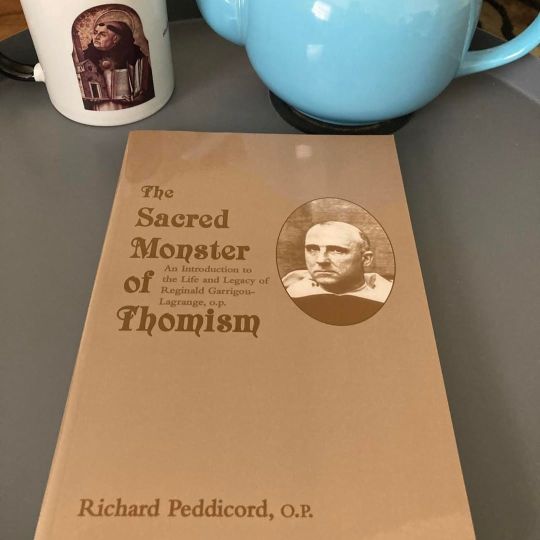

[Part 1] I finished ‘The Sacred Monster of Thomism: An Introduction to the Life & Legacy of Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, OP’ (2005) by Richard Peddicord, OP. Fr. Peddicord, OP was President of Aquinas Institute of Theology in St Louis 2008-2012. Lagrange was professor of dogmatic & spiritual theology at the Angelicum in Rome from 1909-1959. He died early in 1964 a year before Vatican II ended. He has a bibliography of over 50 pages. Chapter 4 deals with his disputations with the philosophies of Henri Bergson & Maurice Blondel & why he opposed them. Chapter 5 deals with his Politics & the conflict it bred for him against Jacques Maritain & Marie-Dominique Chenu, OP. These two chapters are what attracted me to this work. Francois Maurac expressed his disdain for Lagrange, calling him ‘that sacred monster (monstre sacre) of Thomism’. A sentiment that has held the day: identifying his theological rigidity & ecclesiastical repression. This work is an introduction to the life & thought of Lagrange. There is some truth in the oft-repeated line that Lagrange’s favorite sparring partners were dead philosophers & live Jesuits! (Teilhard de Chardin, Henri de Lubac, Jean Danielou, etc.) Lagrange is put into the ‘strict-observance Thomist’ category. Which was a standard way of speaking about the Thomists who taught in the Roman Universities up to Vatican II. He served as advisor to a myriad of doctoral candidates at the Angelicum. Two of note, M-Dominique Chenu, OP, & Karol Wojtyla – the future John Paul II. Lagrange was consulted numerous times by the Holy Office on doctrinal matter. In Rome speak, he was a ‘qualificator’ – one who was qualified as a theological authority. Serving from the pontificate of Benedict XV to John XXIII. In 1955 he was named a ‘consultor’ for both the Holy Office & for the Congregation for Religious. He died 15 February 1964 on the feast of the 14th-century Dominican Rhineland mystic, Blessed Henry Suso, OP. I now begin ‘Soldiers of God In a Secular World: Catholic Theology & 20th-Century French Politics (2021) by Sarah Shortall. https://www.instagram.com/p/CdMgBLXLjlX/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

Fr. Henri de Lubac, SJ has written 4 works on the writings of his friend & confrere Fr. Teilhard de Chardin, SJ. This is the first one I have read, ‘The Faith of Teilhard de Chardin’ (1964). It is a guide, rather than a commentary, through the network of conflicting opinions & a light on the sources of Teilhard’s own inspiration. The work showed me more background into Teilhard’s Western Front experiences as a French Army stretcher bearer. The French Army distributed Sacred Heart badges to their troops, Teilhard both privately & as a Jesuit developed his religious life around the Sacred Heart. One of his billets during the war was at the parish in the village of the Haut-Rhin where the parish priest invited him to preach on the devotion of the rosary. Teilhard had a faithful habit of reciting the rosary daily. In Section 2 Chapter 5 ‘The Axis of Rome’ de Lubac addressed the criticism of Teilhard by Pere Garrigou-Lagrange, OP in 1946 in the periodical ‘Angelicum’. In the previous chapter de Lubac shows how Teilhard was anti ‘modernism’ & in 1919 stigmatized the thought of Alfred Loisy & ‘integrism’. Loisy was a French RC priest, professor & theologian credited as a founder of ‘modernism’. He was a critic of traditional views of Biblical interpretation. He was excommunicated in 1908. Besides Loisy, the philosophers Henri Bergson & Maurice Blondel (both cited by Teilhard) were attacked by Garrigou-Lagrange. So, I am moving up my reading of ‘The Sacred Monster of Thomism: An Introduction to the Life & Legacy of Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, OP’ who was also opposed to Teilhard. De Lubac notes the rules by Pope Benedict XIV on the publication of criticism by theologians outside their own terminology (which Teilhard was for Lagrange). I particularly enjoyed seeing how often Teilhard was aligned with St John Henry Cardinal Newman, & how much of Newman he read. https://www.instagram.com/p/CdHUkPvLI34/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

‘Jacques & Raissa Maritain: Beggars for Heaven’ by Jean-Luc Barre, translated by Bernard E Doering (who wrote ‘Jacques Maritain & the French Catholic Intellectuals’). Both Jacques & Raissa were converted to Roman Catholicism, he from agnosticism & she Judaism. I had read excerpts from his writings in both of my Thomism courses at Duquesne, & in my Morality course at St Mary’s in San Antonio. I was interested in his experience in WW I which caused the death of Charles Peguy at the Battle of the Marne in 1913, & Ernest Psichari in 1913 at Rossignol-St-Vincent. Jacques received a medical exemption from compulsory military service in October 1914. But in 1917 he was considered fit assigned first to the 81st group of heavy artillery at Versailles. But again, in August 1917 after several medical exemptions, he was again declared unfit, after pleurisy as a child. Like Paul Tillich Maritain broadcast to the French over Voice of America during WW II. He was honored after the War as an intellectual in the French Resistance because of his writings clandestinely published in France. Like the work of Fr. Henri de Lubac, SJ in WW II. General Charles de Gaul would appoint Jacques as French Ambassador to the Holy See after the war. As with T S Eliot Jacques & Raissa studied under Henri Bergson at the College de France. Also, as with T S Eliot, he was initially involved with Action Frances & Charles Maurras but broke with him over his antisemitism. Jacques & Raissa had many Dominicans in their life. Pere Humbert Clerissac, OP had served as their spiritual director until his untimely early death. Initially Pere Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, OP was an ardent supporter but would become an adversary after Jacques left Action Francaise & his opposition to Vichy France government. I intend to read ‘The Sacred Monster of Thomism: Life & Legacy Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange’ to get another perspective on their falling out. After the death of Raissa, he lived with the Little Brothers of Jesus in Toulouse. In October 1970 he began his novitiate. Jacques died in April 1973. I received ‘Etienne Gilson’ by Lawrence K. Shook on Tuesday & I am already four chapters in. https://www.instagram.com/p/CbLL2Z4rveq/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes