#Grecizing

Text

A B R A C A D A B R A

The word Abracadabra is said to derive from an Aramaic phrase meaning "I create as I speak." However אברא כדברא in Aramaic is more reasonably translated as "I create like the Word."

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was with God in the beginning. Through him all things were made."

In the beginning was the Word: the Logos, the sound frequency (vibration).

We know that speech means not just any kind of a vibration, but a vibration that carries information.

Thus, I create like the Word.

In the Hebrew language, the phrase translates more accurately as "it came to pass as it was spoken."

History:

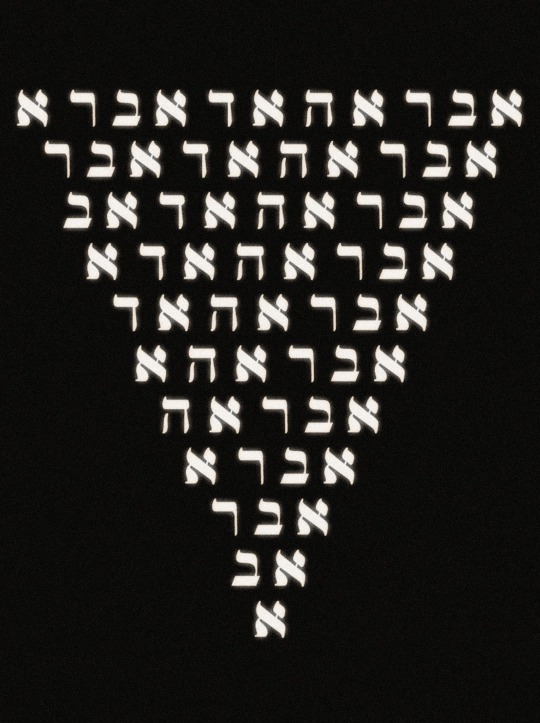

The first known mention of the word was in the third century AD in the work Liber Medicinalis by Quintus Serenus Sammonicus, a physician to the Roman emperor, who suggests to wear an amulet containing the word written in the form of a triangle:

A - B - R - A - C - A - D - A - B - R - A

A - B - R - A - C - A - D - A - B - R

A - B - R - A - C - A - D - A - B

A - B - R - A - C - A - D - A

A - B - R - A - C - A - D

A - B - R - A - C - A

A - B - R - A - C

A - B - R - A

A - B - R

A - B

A

Abracadabra and the Gnostics:

Abracadabra was used as a magical formula by the Gnostics of the sect of Basilides in invoking the aid of beneficent spirits against disease and misfortune. It is found on Abraxas stones, which were worn as amulets. Subsequently, its use spread beyond the Gnostics.

Abraxas:

Have you ever been mesmerized while waiting for the sunrise? As you watch the horizon for that first burst of light, you get swept up in the eternal present moment. With baited breath, your sense of time is suspended, and you’re primed for a miracle. This is the “liminal zone,” the threshold between night and day, between here and there, between this and that. It’s the crossroads where anything is possible. And then the dawn breaks through, like a sudden burst of inspiration, like an act of creation: “Let there be light.” That is the magic of Abraxas, an enigmatic name that has perhaps always been closely associated with the power of the sun. This strange, mysterious name captures that magical, suspended, timeless moment: “all of time as an eternal instant.” Abraxas is the power of infinity—the promise of endless possibilities, the “cosmos” itself. In mythology, Abraxas is the name of a celestial horse that draws the dawn goddess Aurora across the sky. The name suggests a power that is not properly ours but rather a gift from another world.

But what of the name’s origin? It is likely, as an etymologist posited in 1891, that Abraxas belongs “to no known speech” but rather some “mystic dialect,” perhaps taking its origin “from some supposed divine inspiration.” Yet scholars, of course, search for a root. There are speculatory shreds of evidence which suggest that Abraxas is a combination of two Egyptian words, abrak and sax, meaning “the honorable and hallowed word” or “the word is adorable.” Abrak is “found in the Bible as a salutation to Joseph by the Egyptians upon his accession to royal power.” Abraxas appears in “an Egyptian invocation to the Godhead, meaning ‘hurt me not.’” Other scholars suggest a Hebrew origin of the word, positing “a Grecized form of ha-berakhah, ‘the blessing,’” while still others speculate a derivation from the Greek habros and sac, “the beautiful, the glorious Savior.” The name has appeared in the ancient Hebrew/Aramaic mystical treatises The Book of Raziel and The Sword of Moses, and in post-Talmudic Jewish incantation texts, as well as in Persian mythology.

An interesting occurrence of Abraxas is found in a papyrus from late antiquity (perhaps from Hellenized Egypt, though its exact origin is unknown). The papyrus contains “magical recipes, invocations, and incantations,” and tells of a baboon disembarking the Sun boat and proclaiming: “Thou art the number of the year ABRAXAS.” This statement causes God to laugh seven times, and with the first laugh the “splendor [of light] shone through the whole universe.”

The Basilideans, a Gnostic sect founded in the 2nd century CE by Basilides of Alexandria, worshipped Abraxas as the “supreme and primordial creator” deity, “with all the infinite emanations.” The god Abraxas unites the opposites, including good and evil, the one and the many. He is “symbolized as a composite creature, with the body of a human being and the head of a rooster, and with each of his legs ending in a serpent.” His name is actually a mathematical formula: in Greek, the letters add up to 365, the days of the year and the number of eons (cycles of creation).

“That a name so sacredly guarded, so potent in its influence, should be preserved by mystic societies through the many ages . . . is significant,” notes Moses W. Redding, a scholar of secret societies. Redding suggests that only in Freemasonry has this “Divine Word” been “held in due reverence.”

In Kabbalah:

As a carpenter the creator employs tools to build a home, so G'd utilized the twenty-two letters of the alef-Beit (the Hebrew alphabet) to form heaven and earth. They are the metaphorical wood, stone and nails, cornerposts and crossbeams of our earthly and spiritual existence. As in abracadabra "Αύρα κατ' αύρα" אברא כדברא, as he, she, it created the universe with; the Letter, The word, and the number.

As Kabbalist sages say G'd created the alef-beit, before the creation of the world. "The Maggid of Mezritch" explains this on the basis of the first verse in the Book of Genesis “בראשית ברא אלקים את השמים ואת הארץ—In the beginning G'd created the heavens and the earth.” Beresheet Barah Elokim Et (in the beginning God created the) The word את, (es or et) is spelled with an aleph, the first letter of the aleph-beit, and a tav, which is the last. The fact is, את, es, is generally considered to be a superfluous word. There is no literal translation for it, and its function is primarily as a grammatical device. So why is “es” present twice in the very first line of the Torah? It suggests that in the beginning, it was not the heavens and the earth that were created first. It was literally the alef-beit, aleph through to tav. The alpha and the omega, Without these letters, the very Utterances with which G'd formed the universe would have been impossible the Baal Shem Tov explains the verse, “Forever the words of G'd are hanging in the heavens.”

The crucial thing to realize is that G'd, creator, source did not merely create the world once. His Her It's words didn’t just emerge and then evaporate. Rather, G'd continues to create the world anew each and every moment. His Her It's, words are there constantly, “hanging in the heavens.” And the alef-beit is the foundation of this ongoing process of creation.

According to Kabbalah, Cabbalah and Qabbalah sages and scholars, when the same letters are transposed to form different words, they retain the common energy of their shared gematria. Because of this, the words maintain a connection in the different forms. We find a classic example of this with the words (הצר, hatzar, troubles), (רצה, ratzah, a desire to run passionately into the “ark” of spiritual study and prayer) and (צהר, tzohar, a light that shines from within). All three words share the same three letters: tzaddik, reish and hei in different combinations. The Baal Shem Tov, explains, the connection between the words as follows: When one is experiencing troubles (hatzar), and one runs to study Spiritual txts and pray with great desire (ratzah), one is illuminated with a G'dly light from within (tzohar) that helps him or her transform there troubles into blessings, as it is said that the source of the twenty-two letters is even higher than that of the Ten Commandments.

As it states: “With you, is the essence of G'd", בך means “with you.” The (Beit which has a gematria of 2) and the (kaf = 20) added together equals 22. Through the twenty-two letters of the alef-Beit, we are all connected to the monad, G'd, Allah الله, the source, and each other through our words and language as words hold power as that which makes us All unique is language as language weaves everything together. These are the teachings of our holy teacher, as the The Zohar affirms that every sentence, every phrase, every word, and even every letter of the Bible exists simultaneously on several levels of meaning. This sacred work clearly declares, “Woe unto those who see in the Law nothing but simple narratives and ordinary words! . . . Every word of the Law contains an elevated sense and a sublime mystery.”

[Except from Path of the Sun Keepers by Paul Francis Young]

“Words have a magical power. They can bring either the greatest happiness or deepest despair; they can transfer knowledge from teacher to student; words enable the orator to sway his audience and dictate its decisions. Words are capable of arousing the strongest emotions and prompting all men's actions.”

--Sigmund Freud

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading A Critical History of Early Rome by Gary Forsythe. As the title suggests, Forsythe is deeply skeptical about the value of ancient narrative sources for early Roman history (chiefly Livy, of course, but also Dionysius of Halicarnassus and Plutarch). It's a very different tack from the standard English-language work on the period, Tim Cornell's The Beginnings of Rome, which places more credence in the literary tradition. In general, I incline to Forsythe's view--the Romans had a remarkable knack for mythologizing their own history, and writers like Livy, working in a heavily Grecizing historiographic tradition, tend to find (or create) forced parallels between early Rome and Greece (e.g. casting the defeat of the three hundred Fabii at Cremona as the Roman equivalent of Leonidas' last stand at Thermopylae). But even if you happen to be less skeptical than Forsythe, he's well worth a read, not least for the care he takes at placing Rome's development within a broader Mediterranean context.

26 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Our translations, even the best, proceed from a false premise. They want to germanize Hindi, Greek, English, instead of hindi-izing, grecizing, anglicizing German. They have a much greater respect for the little ways of their own language than for the spirit of the foreign work. The fundamental error of the translator is that he maintains the accidental state of his own language, instead of letting it suffer the shock of the foreign language. He must, particularly if he translates a language very remote from his own, penetrate to the ultimate elements of language itself, where word, image, tone become one; he must widen and deepen his language through the foreign one.

Rudolf Pannwitz, Die Krisis der europäischen Kultur (1917)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“A (Very) Young Mother To Be” based on Luke 1:26-45

The Christmas stories function as gospels in miniature: establishing themes, offering foreshadowing, and even telling parts of the story in smaller but parallel ways.1 One of the little connections I first noticed this year is that in the Gospel of Luke, Jesus travels several times between the seat of his ministry in Galilee and the seat of Jewish power in Judea. This text has his mother Mary traveling from Galilee, to Judea, back to Galilee, and then BACK to Judea all while pregnant!

Luke's themes – in both the Gospel as a whole and in the Christmas story - include a value of women, a focus on the marginalized, and attention to the Holy Spirit. Luke chapter 1 spends a lot of time on Zechariah, Elizabeth, and John the Baptist. Luke is the only gospel to claim that Elizabeth and Mary are kin, as well as the only one to focus on the experiences of Elizabeth and Mary. Scholars have pointed out that Luke is intentionality setting up a rather enormous proposition.

Namely, Elizabeth's pregnancy story sounds like a common Hebrew Bible story. According to Genesis none of the patriarchs and matriarchs were about to procreate without an exceptionally long wait and Divine intervention. Elizabeth and Zechariah are an older couple, without children, who have gone past childbearing age. Elizabeth and Zechariah's story sounds most like Abraham and Sarah's, although it also connotes the birth of Samuel. God intervenes, and the VERY unexpected happen, or at least it would be VERY unexpected if it weren't so common in the Bible.

Mary's pregnancy story, on the other hand, is novel in the Bible. It hasn't been told before. The ancient Greeks and Romans may have hand virgin birth stories as commonly as we have superhero movies, but this wasn't part of the Jewish tradition.

Elizabeth is an old woman, thought to be barren, who has a child because of Divine intervention. Her story resounds with Hebrew Bible echoes. Mary is a young woman, thought to be pre-pubescent, who is ALSO said to have a child because of Divine intervention. Her story has an entirely new tune and tone.

Scholars think that Luke is intending for Elizabeth's son, John the Baptist, to represent the end of an age; while Mary's son, Jesus, represents the beginning of another age.2 In that case, having the two pregnant mothers residing in the same home in the Judean hills for three months, having Mary present for Elizabeth's birth, having Elizabeth's pregnancy function as proof for Mary's experience, and having the women related to each other and spending time sharing their experiences, is potent with meaning.

Now, it does turn out that the idea of one age ending and another beginning with the births (and deaths) of those men does have some truth to it. After all, a miscalculation of the date of the Birth of Christ was the original premise of our Western Calendar. Time has been calculated since that moment. And, since Luke was writing about 60 years after the death of Jesus3, but the time these stories were written down, the sense of an era ending another beginning was presumably felt deeply. Setting up these two main characters as the icons of change indicates how important the early Christian community thought their lives were.

Now, there is a reasonably high level of certainty that Jesus was a disciple of John the Baptist AND that there were people who had wondered if John the Baptist was the Messiah. This means that the followers of Jesus – both during his life and after his death – had to explain why they thought THEIR guy was THE guy, and the OTHER guy wasn't. I suspect some of the reason for the story we read today is to clarify that stance. It also serves acknowledge how closely tied their lives were and how closely tied their message were. Today, I think it functions well to remind us that the “end of an era” and the “beginning of an era” still operated in continuity – with a shared understanding of God and of God's vision for the world.

Luke 1 is a chapter of waiting. It runs for 80 verses, and yet it isn't until chapter 2 that Jesus arrives. Luke 1 is a little bit of Advent and of Christmas Eve – the waiting and the not-yet. Luke 1 gets us ready and hungry, and anticipating the arrival of the Christ-child. It makes us wait from the annunciation, through travels and songs of praise, through John the Baptist's birth and circumcision, through the faith struggles of his father, and even through the start of John the Baptist's ministry before the chapter ends and we get to turn to the birth of Jesus.

It feels a bit like we are waiting with Mary, aware of the changes that are about to happen, seeing the changes in her body, wondering about the impact (she's said to ponder a lot), but without yet holding the baby nor forming him in his faith. Luke sets up Mary to be the sort of woman you can believe could raise a son like Jesus. She is named for Miriam, a wise and faithful leader, the sister of Moses.

(Mary is the Greek-i-fied version of the Hebrew Miriam. It isn't clear to me if she would have been called Miriam, but it was written down in Greek as Mary or if the Greek influence was strong enough that she lived in that tension of being named for a Hebrew heroine, but with the itself Greek-i-fied. By the way, the word for that is “grecized” but I didn't think we all knew that. Or, rather, I didn't previously know that.)

Mary is also BRAVE and FIERCE. If you remember a later story of Jesus, the one with the woman who had been accused on adultery, the one they wanted to stone – because that was the prescribed punishment for such an act – then you may note why an engaged woman agreeing to a pregnancy from not-her-fiance was so brave!! An engaged woman was seen as fully the “property” of her husband, and adultery was defined as someone sleeping with someone else's property, and a pregnancy when the couple hadn't engaged in procreative activities would generally serve as good proof of adultery. Yet, in Luke, this isn't a problem!!! For Luke, Mary speaks and is believed, and there isn't any issue at all. I like Luke. He trusts women, and he gives them voice!

In many ways this presentation of Mary becoming pregnant by God reflects the Greek and Roman influence over that region as much as her name does. This was a fairly common story in Greek and Roman myths, although, I gotta give it to Luke, this is the only story in which the woman is asked for CONSENT before getting pregnant.

Mary DOES give consent. She knows what it could cost, but she is willing. As the story goes on, she sings God's praises for being willing to lift her up by giving her this task (#tomorrowsSermon)

Now, much later in the Gospel, Jesus will be put to death because of his faithfulness to God's message and the building of God's kindom. However, in this very early passage in Luke 1, we see that his mother was also willing to take those risks in order to serve God and build the kindom. She was likely very young (on the cusp of puberty), very poor, and rather profoundly disempowered, but she is given a choice about her life and she chooses to take a risk for God's sake.

Elizabeth is also named for a Hebrew heroine, Aaron's wife (Aaron was brother to Moses and Miriam), whose Hebrew name has been translated into Greek. I choose to interpret from this story that Elizabeth was a mentor figure to Mary, a safe place Mary could go and ponder. It has already been said in Luke 1 that John the Baptist was going to be gifted with the Holy Spirit, and in this scene it is clear that the gift is so strong as to move his mother too! Elizabeth is presented as speaking a truth that much of the world will never see, and it is presented as if God's own wisdom is able to move through her.

Elizabeth praises Mary BOTH for the wonder of having Jesus in her womb AND for faithfulness in believing God when she was told what would happen. I appreciate that this praise comes in two parts, too much of Christianity has only praised Mary for being the mother of Jesus, and missed that the story presents her as one of his teachers and mentors as well. Elizabeth expresses shock that she could receive the gift of a visit from such an important woman, and that the baby in her womb recognized the wonder of what was happening.

Luke 1 reminds us why the birth itself even matters! Luke 1 sets us up to notice that when God is up to something, God doesn't tend to pick the already powerful and noteworthy figures to do the work! Luke notes that God works with and through women, and the marginalized, through that unable to be controlled Holy Spirit. Luke sets us up to notice that something BIG is about to happen and it will change the world.

Which perhaps leaves us with a very important question: how has the birth of Christ changed the world FOR US, and how are our lives and actions different because of it? The era we live in has been formed by these stories, and they are ours to ponder. Are we ready, like Mary, to answer the call for radical change with “let it be with me according to your word.”? May we be. Amen

1John Dominic Crossan and Marcus Borg point this out in The First Christmas: What the Gospels Really Teach about Jesus' Birth (USA: HarperOne, 2007)

2Fred B. Craddock, Luke in the series Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching (Louisville: John Knox Press, 1990) p. 29. This is one of several times this theory has been written, but he said it in a particularly accessible way.

3I'm taking this from the estimate that Luke was written in about 85 CE, while Jesus was born in about 5 BCE, and lived about 31 years. The “mid eighties” guess comes from R. Alan Culpepper, “Luke” in Leadner Keck, ed. , The New Interpreter's Bible (Nashville: Abingdon Press: 1995) p. 8.

--

Rev. Sara E. Baron

First United Methodist Church of Schenectady

603 State St. Schenectady, NY 12305

Pronouns: she/her/hers

http://fumcschenectady.org/

https://www.facebook.com/FUMCSchenectady

#Merry Christmas#FUMC Schenectady#UMC#Schenectady#Thinking Church#Marcus Borg#John Dominic Crossan#Luke is a feminist#Passes the Bechdel Test#Mary#Elizabeth#Greek Influenced Hebrew Culture#Rev Sara E Baron#Advent 4#Christmas Eve#We laugh#Luke 1#Consent

0 notes