#I think Fanny is the most drawn character on this blog

Note

I got a request

Can you draw Fanny as a blue and white tabby cat it’s apart of my BFDI pet AU

so I found the design you probably meant but I found it too late..

So instead you get a actually tabby cat .. sorry .

#half-asleep doodles#osc#bfb#Tpot#tpot fanny#bfb fanny#I think Fanny is the most drawn character on this blog

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

I posted 478 times in 2022

That's 478 more posts than 2021!

246 posts created (51%)

232 posts reblogged (49%)

Blogs I reblogged the most:

@thatscarletflycatcher

@taciturn-nerd

@firawren

@redwooding

I tagged 412 of my posts in 2022

Only 14% of my posts had no tags

#jane austen - 282 posts

#mansfield park - 135 posts

#pride and prejudice - 116 posts

#fanny price - 67 posts

#sense and sensibility - 62 posts

#emma - 52 posts

#elizabeth bennet - 48 posts

#persuasion - 45 posts

#northanger abbey - 43 posts

#reblog - 42 posts

Longest Tag: 134 characters

#i want to make a huge spreadsheet and rate every physical description by reliability and objectiveness but when would i find the time!

My Top Posts in 2022:

#5

Mr. Collins was not a sensible man, and the deficiency of nature had been but little assisted by education or society... Having now a good house and a very sufficient income...

I really dislike adaptations have made Mr. Collins older than his actual twenty-five years. It seems like they want to lean into the Gross Older Relation I Must Marry trope but that is NOT what is happening here and I think it’s more significant to recognize the truth.

As far as Elizabeth knows, there is nothing wrong with Collins. He doesn’t gamble (or he wouldn’t go on about it at the party), we don’t see him get drunk (Uncle Phillips is hinted to do that), he doesn’t seem violent/prone to outbursts of temper (he could have when Lydia was rude while reading), and he’s not ugly as far as we know. His manners are very formal, which isn’t really shown in adaptations either. And he’s young, he’s only four years older than Elizabeth.

The point is not that he’s a GORIMM. I think the point is that he’s fine, but Elizabeth knows she’ll never like him and that’s enough. Mr. Collins offers a good deal: domestic security, future wealth, and no danger. However, Elizabeth understands that without intellectual compatibility, she will be unhappy. This is what makes her a heroine.

By making Collins old and kind of gross, the adaptations actually erase a lot of Elizabeth’s motivations and strength. The reaction to Collins becomes more visceral than intellectual, and that’s a problem.

489 notes - Posted November 15, 2022

#4

Jane Austen Charted #4

Darcy’s Irrepressible Feelings Graphed

X Axis: Time

Y Axis: Level of Ardent Love

Also included: Proposal DANGER line

497 notes - Posted November 23, 2022

#3

The Wickham Fund

According to Darcy, he paid Wickham 3000 pounds instead of his inheritance.

According to Mrs. Gardiner, Darcy paid approximately 3000 pounds to secure the wedding of Wickham and Lydia.

Obvious Conclusion: Mr. Darcy has a 3k Emergency Fund that he keeps having to use for Wickham.

509 notes - Posted August 9, 2022

#2

Jane Austen’s Warning:

A lot of people tell me the Mrs. Smith/Mr. Elliot plot is a lose thread or Jane Austen would have went back and fixed it, but when you read all of her books it's a very clear repeat of an important theme: men are often not what they appear.

Northanger Abbey: Don’t just trust your brother when he tells you his friend is a good guy, judge for yourself. It was John Thorpe, your brother was dead wrong. Also, your creepy feelings about General Tilney were right, just more mundane.

S&S: The passionate, open, charming fellow who is obsessed with your sister? Turns out he’s a debt-ridden, teenage-seducer. It was good to doubt him, Elinor, he wasn’t being completely straight with you. The good ones have honour.

P&P: Superficially charming man is super bad news, man with snobby manners has a heart of gold underneath. Elizabeth is intelligent, the novel shows us that anyone can be drawn in. Elizabeth was unwilling to change her first impressions and take in new information.

Mansfield Park: Some men pretend to be in love for fun, Fanny’s clear-sighted judgement of Henry Crawford keeps her safe from his attack on her heart. We are shown that these men can seduce friends and guardians against you. Fanny refuses to “fix” Henry or accept him on his word, he needs to show her that he has changed before she will.

Emma: The superficially charming man was already engaged and was tricking you! The other charming, attractive man was actually a petty jerk! The plain-spoken, honest man was always the better choice.

Persuasion: Anne has a gut feeling that she can’t fully put words to about Mr. Elliot that he is bad news. She cannot even fully justify it to herself. ANNE, YOU WERE RIGHT.

Again and again, we are told that women need to trust their judgement, look for more evidence into a man’s character/past, and mistrust charm/looks without a basis of goodness. Anne figuring out that Mr. Elliot is evil isn’t anti-climactic, it’s a proof that her judgement is sound. It’s a reminder that one should never rush into a marriage without knowing more about a man’s past. Because for a woman especially, it can end horribly.

544 notes - Posted August 24, 2022

My #1 post of 2022

Jane Austen associating the word "rational" with women over six books:

Do not consider me now as an elegant female, intending to plague you, but as a rational creature, speaking the truth from her heart. - Elizabeth Bennet, Pride & Prejudice

“But I hate to hear you talking so like a fine gentleman, and as if women were all fine ladies, instead of rational creatures. We none of us expect to be in smooth water all our days.” - Mrs. Croft, Persuasion

She dearly loved her father, but he was no companion for her. He could not meet her in conversation, rational or playful. - Emma Woodhouse, Emma

“Oh! never, never, never! he never will succeed with me.” And she spoke with a warmth which quite astonished Edmund, and which she blushed at the recollection of herself, when she saw his look, and heard him reply, “Never! Fanny!—so very determined and positive! This is not like yourself, your rational self.” Fanny Price, Mansfield Park (we know that this is very much her rational self, also after a marriage proposal)

Elinor agreed to it all, for she did not think he deserved the compliment of rational opposition. -Elinor Dashwood, Sense & Sensibility

You talked of expected horrors in London—and instead of instantly conceiving, as any rational creature would have done, that such words could relate only to a circulating library, - Henry Tilney, teasing his sister, Northanger Abbey

598 notes - Posted November 19, 2022

Get your Tumblr 2022 Year in Review →

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

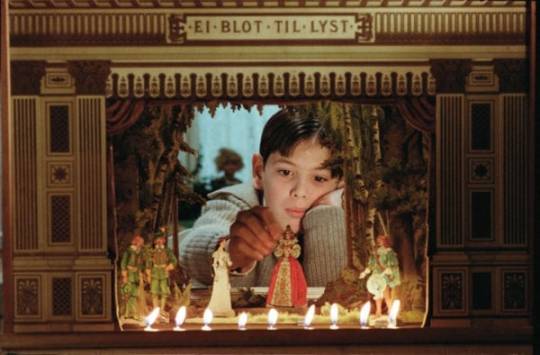

Film #728: ‘Fanny and Alexander’, dir. Ingmar Bergman, 1982.

It's not often I have to start one of these analyses by looking at the question 'What is cinema?' but Ingmar Bergman's filmography is so dense and wide-ranging that it was bound to happen sooner or later. His 1982 magnum opus Fanny and Alexander was originally imagined as a television miniseries and produced in a five-hour version, which was cut down to 188 minutes for a cinematic release. The longer miniseries was released subsequently. According to the book, the version under discussion is the 188-minute cinematic cut, although reading up about the film there are some details from the five-hour version that I think are particularly illuminating. It's arguable that referring to these details (from an extended cut I haven't seen, no less!) is like citing page numbers from Tolkien when talking about Peter Jackson's Hobbit films, but this is my blog, so I'm not going to wade into the reeds on this one.

Anyway, the reason the provenance of Fanny and Alexander feels a little more relevant is because Scandinavia has a rich history of crossover between film and television, with some of its most prominent directors working in television drama production as well as releasing feature films. With the rise of streaming services and prestige television this distinction is a little less important, but to the best of my knowledge Martin Scorsese has never directed an episode of Masterpiece Theater, which is the best analogy I could come up with. Bergman is a director who has clearly given deep thought to the differences between structuring, themes and acting for television and feature film, and the end result is that the three-hour cinematic release feels like three one-hour episodes chained together. The same characters, and an ongoing narrative, but strikingly different themes and tones across each of them.

The first hour introduces our protagonist, Alexander (Bertil Guve), a boy with a feverish imagination. In the first few moments of the film we already see through his eyes a statue moving, and we can get an instant sense of his creativity, but also some of the emotional myopia specific to children - Alexander is withdrawn and distant when he pleases and recklessly dishonest when he pleases, and is constantly blindsided by how others react to his behaviour. This first 'episode' takes place on a busy Christmas Eve as the entire Ekdahl clan gathers at the home of the grandmother Helena (Gunn Wållgren, in her final performance). Helena acts as the emotional centre of the family for the majority of the film, and right from the beginning we often see the other family members considering their own actions in relation to what Helena would think. Some of these characters are drawn in great detail to prepare us for their appearances later: the romance between the married Gustav Adolf (Jarl Kulle) and the family's maid, Maj (Pernilla August) is an ongoing plot, for example. Other characters are carefully drawn, such as Carl, the philosopher, who hates himself for hating his wife, and who only seems happy entertaining the children with his performative farting - but Carl only appears in this section of the film. Bergman is drawing a rich cast of characters that give the world a feeling of population; an intricate web of relationships.

Alexander's father, Oscar (Allan Edwall) gives a rousing Christmas speech to the employees at the theatre he operates, focusing on the differences between the 'little world' of the playhouse and the 'bigger world' outside. He observes that the theatre sometimes succeeds at reflecting the real world, but that the theatre is also an opportunity to escape those real cares - a theme that will be repeated at the end of the film.

Our second episode shifts the focus a little smaller, to the relationship between Alexander and his immediate family. Oscar dies of a stroke while rehearsing the role of the Ghost in Hamlet, and his mother Emelie (Ewa Fröling) is immediately wooed by the local bishop, Edvard (Jan Malmsjö). Emelie immediately learns she has made a mistake when Edvard is strict and controlling towards her and the children, demanding they rid themselves of their possessions and limit their contact with her family. Seemingly out of a mix of retaliation and grief, Alexander's lies and fantasies become more outlandish, culminating in his telling Edvard's maid that he saw the ghosts of Edvard's former wife and children, who announced that Edvard was responsible for their deaths. The maid immediately tells Edvard who, while Emelie is away secretly visiting her family, punishes Alexander and confines him to the attic.

Emelie seeks help from her family, and salvation comes in the form of Isak Jacobi, a local pawnbroker and old flame of Helena. Isak smuggles the children out of the house while Emelie, who is now pregnant with Edvard's child, remains.

The focus is narrowed once more in the third episode, which almost exclusively revolves around Alexander's stay with Isak and his nephews. One is a master puppeteer and the other is a mysterious invalid who seems to have the ability to control the minds and actions of others (I say 'seems' because the film is quite deliberately vague on this point - a decision I'll come back to later). The two nephews either cajole or enable Alexander to bring about the death of the bishop, partially in conjunction with Emelie's decision to heavily sedate her husband so she can leave. The death of the bishop means that Alexander, Fanny and their mother can return to their extended family once more, and the film ends at a lunch celebrating a double christening: Maj's child with Gustav Adolf, and Emelie's child with the deceased Edvard. Gustav Adolf gives a speech which is quite similar to Oscar's in the first hour of the film, extolling the importance of actors in distracting us from life's problems.

The fact that the film opens and closes with similar speeches about the role of theatre in life is telling, because Fanny and Alexander feels like a drawing-room theatre trilogy. Many of the films on the list have drawn their similarities to theatre in an explicit way (think of The Golden Coach, which uses a theatre as a framing device, or Diva, which begins and ends with diegetic opera performances on a stage), but Bergman is working on a slightly more implicit and thematic level. His film is full of literal actors and literal performances, sure, but he also encourages us to think about life through the lens of these performances, rather than just the performances per se.

Here's an example: Oscar's death happens during a rehearsal of Hamlet, in which Oscar is playing the role of the ghost of Hamlet's father. Alexander is in the audience for this rehearsal, and witnesses his father's collapse. The rest of this act plays with the tropes of Hamlet. Alexander is haunted, but not by the ghost of his father (the person who sees Oscar's ghost in this act is Helena). Rather, Bergman uses the trope of 'a ghost attesting to a wrongful death' - Alexander claims to see ghosts who accuse the bishop. A hasty marriage following the death of the protagonist's father is also central to this act, but the causality of it is out of kilter with the narrative being put right in the foreground. Either Bergman, or Alexander, or maybe both, is trying to make life make sense by recycling parts of Shakespeare's play, but none of the pieces quite fit together. At the end of the film, the bishop has been killed, but unlike Hamlet, Alexander stays alive, and the implication instead is that he will forever be haunted by the bishop.

But why should he be? I think it's pretty illuminating from a thematic point of view that at no stage do we really get confirmation of whether the ghosts that Alexander sees are real (at least in this version - in the five-hour version we apparently see the ghosts too, but I can't determine whether we see them in real-time or if they're only show through the frame of a story Alexander tells). The behaviour of the bishop in response to Alexander's accusations is interesting, because Jan Malmsjö plays his role with the menace that makes you believe he could be capable of such a thing. One of three possibilities is true: that the bishop killed his wife and children and the ghosts are real, that the bishop didn't and the ghosts are fictions dreamed up by Alexander, or that Alexander imagines the ghosts and yet has lucked into revealing the truth about the bishop. Bergman doesn't come down strongly on this question, and even the reveal at the end that the bishop's ghost now haunts Alexander doesn't help matters one way or the other. All of these explanations are plausible - either the result of a legitimate haunting or the fevered imagination of a guilt-ridden child.

The same questions arise again when the bishop dies. At least according to what the film tells us is true, the following happens: the bishop's bedridden aunt draws a kerosene lamp closer to her, it topples and sets her alight, and then she fatally injures the heavily-sedated bishop in her attempts to get help. It appears, according to the narrative, that the aunt pulls the lamp closer under the influence of either the puppeteer, who is seen drawing a light closer directly juxtaposed with the aunt doing the same, or under the influence of the other nephew, guiding Alexander to unleash his most destructive psychic impulses. Again, though, both these supernatural explanations are in conflict with the natural explanation.

Whichever of the explanations for these events Bergman wants us to believe is true, it is apparent that these imaginative explanations aren't a lot of help to Alexander: most of the time, in fact, they make things worse. It ultimately doesn't matter too much whether Alexander sees real ghosts or simply imagines them, whether he says so out of childishness or malice: his punishment for claiming to see them is real either way. If Alexander believes himself to be enacting a skewed version of Hamlet's story, the lessons of the play don't benefit him at all. At the end of the film, with the bishop dead (and his death shown in excruciating detail in a flashback), the stories that Bergman uses to try and make sense of the world are shown to be of little help. That brings us back to the speeches that Oscar and Gustav Adolf give, with Gustav Adolf in particular imploring the family, "Don't be sad, dear splendid artists - actors and actresses, we need you all the same. You are there to provide us with supernatural shudders... or even better, our mundane amusements."

What this speech doesn't tell us art and theatre can do is solve problems. It tells us stories of power and the supernatural, but Bergman's film is refreshingly pragmatic when it tells us that art is not powerful or supernatural in itself. It is fiction, and even when it is telling us that amazing things are possible, that doesn't make the amazing things the story depicts any more real than if it said they were impossible.

Fanny and Alexander does seem to have one moment that displays an outright impossible thing. When Isak smuggles the children out of Edvard's house, he hides them in a chest he has offered to purchase from the bishop. He sneaks them into the chest and covers them with a small cloth - clearly too small to adequately hide them. The bishop catches on to Isak's plot, and throws the chest open, but does not see the children inside. He runs upstairs to try and locate them, while Isak falls to his knees and screams in frantic, rageful prayer. Upstairs, Edvard finds the children lying on the floor, still and rigid, but Emilie screams at Edvard not to touch them, and Edvard obeys. The children, apparently still in the chest, are meanwhile snuck out of the house.

What on earth are we to make of this? The film doesn't otherwise give us any reason to believe in the power of God, either from a Christian or Judaic perspective (and it's very difficult to tell if Bergman is drawing on particular strands of Jewish mysticism or just general Semitic stereotypes). I've been influenced here by another blog, Seeing Things Secondhand, whose author is, I believe, an English teacher in the States. Writing about Bergman's work as a whole, he says "God has been uncaring (The Seventh Seal), impotent (The Virgin Spring), terrifying (Through a Glass Darkly), missing (The Silence). Here he is a puppet of man." Isak, and the nephews, Aron and Ismael, evoke God's power to their own ends, and it is always imbued with a hint of menace. After all, if you have access to this type of power, what wouldn't you use it for?

The power Isak and his nephews wield might be real, it might be explained away by a complicated chain of causes, but either way it's not something that the Ekdahl clan has access to. What they have is far more toothless but it is also not tinged with threat at every turn. Isak in particular, straddling the world of the Ekdahls and the world of mysticism, seems like a genial old man who should not be pushed to extremes. In comparison, the rest of the family, as turbulent as their lives are, seem ever-gentle. And that's okay. Their job in the theatre isn't to solve problems, but just to tell us stories.

Fanny and Alexander raises constant interesting questions, then, but the story that it tells across its epic runtime floats, barely tethered, above them. Rick Moody, writing for Criterion and wondering about how autobiographical the film is, suggests that the solution to a film like this is just "to realize that it is the interrogatives of which life is composed. Maybe Fanny and Alexander is simply an autobiographical yarn as Alexander would tell it, so that Bergman and Alexander now appear to us to be one and the same narrator of the tale. Maybe Alexander is Bergman refracted, in this instance in the convex mirror of art, where strange happenstances are routine and tidy answers are hard to come by. Or maybe Bergman is somehow Alexander’s own dream, from which the boy has yet to wake."

That wording resonates with the final scene of the film, in which Emelie presents Helena with the script for the next play the theatre intends to present, August Strindberg's A Dream Play. Sitting down with Alexander resting his head on her knee, Helena begins to read: "Anything can happen. Anything is possible and likely. Time and space do not exist..." It's an oddly comforting conclusion, freeing the characters and the audience from the expectation that anything must be explained. All that needs to happen is for us to watch and to narrate, and life will go on in that gentle way.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Headcanon:

The ‘Actress’ Motif and Sophie Hatter.

Companion piece to Self-Perception, Self-Restraint, and Conflict in Sophie Hatter.

A theme that has been going throughout this blog’s writing (and in my interpretation of Sophie) has always been themes surrounding theater and performance. It ranges from addressing the young Hatter to work through ‘masks’ that best work per situation (this’ll date to pre-curse in canon and standard in others) to the stage that everyone works on to this thing we know as life.

She refers to herself as a cognizant actress to take on many shapes and forms, easily transitioning and adapting physically and emotionally (feelings, as opposed to long-term sentiments) whenever possible. Her adaptability isn’t as flexible when it comes to her own mentality, and emotions, which itself is jeopardized and rigid most of the time. However, what matters to her is how she is perceived and keeping all in order and in check as she is, after all, responsible for providing to others.

Emotional intimacy, in which she opens herself up to others, is among the hardest things for her to express. She has placed too many boundaries and walls around to find herself comfortable to do this in any normal circumstance. And this is a result of her own deliberate management and compartmentalization of her own person. Which is basically saying ‘her behaviors and thought process has harmed her normal processes and her own perception of herself. It is a removal from understanding herself entirely and placed it in the back of her mind. That is itself an entirely different topic, but it does relay back into this current headcanon. More details on that may be found here: Is your muse very emotionally intimate?

Performativity is an important asset to how Sophie functions. She has already withdrawn her own interests and future intentions at a relatively young age (book canon wise) in order to pursue raising and aiding her youngest sister to seek our her fortune. This also includes her other sister, the second-born, by keeping her in line and helping her navigate through her wants. Being perfectly honest, Sophie did raise both of her sisters and Fanny, her mother, gave her her rightfully deserved acknowledgement and credit for that after being missing for quite some time. Back on topic, this is the first instance to where Sophie begins her ‘performance’and reworking herself to better meet the needs of others. The first mask for her to where was the one meant for the most important people in her life: her sisters.

As for imagery, the most consistent would be masks, the stage, dancing (specific performance), marionettes (and being controlled by strings), the ‘audience’ being connected to overwhelming (and public) eyes always watching her and recitals. All of it revolves around how she sees herself in the real world interacting with everyone else, making her distinctively separated from the others around her. And boy, Sophie’s views on what she deserves and what others deserve is a topic.

The quote below is an excerpt that goes thoroughly into the mentioned imagery. It is specifically a dream sequence Sophie has that encapsulates her own experience and fears that ties all this together.

( White, red, and gray dance in the mind of the dancer; dissonance spinning her around by the wooden controller that fate held onto. Entangled by responsibilities, her feet drag, and the wires dig into her light skin along her neck, arms, legs, and across her exposed body. The same sequence, dance, and song – the marionette towed onto the stage takes her place – first position, heels touching, and feet outward with shoulders flat and body motionless.

A jerk to the left from the strings, one arm now up, and her feet are drawn to the fifth position. Assemblé, the left foot behind her right, gives a small kick forward, and once that rests, the right foot and arm continue the pattern. Within the same step, arabesque. Both arms out on her sides slightly angled forward to the house, left leg extending behind her body with her right leg firmly straightened. Before long, she turns to position.

Rond de jambe to create grace, tendu to keep simple, sissonne to change the pace, and passé to change her feet position a little. Each rigorous moment had a particular formation to follow, an order that must be obeyed. Performing for the faceless and unseeable, they still demand entertainment, and she must appease.

Echappé to the stars and emboité for impressions, each step now was exigent and the breath in her throat she held. Jumps, bends, snaps, it must be according to the motions of wires that compose and direct her required movements. Glistening her throat was sweat, trailing down a major muscle tensing, yet now she held the house in her palm.

One arm pulled back over her shoulder, back bent backward, her head craning back to greet the audience with her eyes, and her left up, pointing forward to the direction of the stage. A waltz dip for only one, a dance for two yet she must perform in solitude. Her greatest feat, making illusions of balance when impossible.

Rrrrriiiiippppp. All she could feel was cotton. Just like a well-loved and well-traveled toy, sometimes they tear after a while. White cotton plush tumbling out of the split down her abdomen, the chaotic tune in her ears now white noise, a stillness hangs over the theater. But why was it so hot? Why were her appendages twitching, and why now of all places? Could she not continue? She must–…

Her legs failed her – no, no, she failed them. The conductor to the show, the audience, the faces she knew and loved. Perfect form collapsing to the ground, her body descending to the wooden floor with her arms splayed and legs luxate stiffly.

How odd, this dream never ends like this. But, it’s a kinder dream then if it does. )

DRABBLE RESPONSE TO @/diverse-hearts’ ASK.

Now, onto another business revolving around this motif: the mental state of Sophie’s mind because the imagery, references, and comparisons whenever I write are connected to each character by third person narrative. Basically, any time I do write for a character, their unique particulars bleed through into the writing which makes it their own and provides the capacity available to experience what they’re thinking, going through, rationalizing/understanding something, etc.

Having this constant duality between the perceived world and the real world since young, Sophie’s mind oft bleeds into relying and using her active imagination, which was of the many things that were kept ‘in line’ as a child. It is something that is persistently with her as she has a tendency of vicariously living out different lives and imagining herself as a completely different person or face (thank you HMC musical for validating this HC). But, she would most often take on imagining what other people life and what kind of fun and excitement and fortune was in their lives. Case and point: the entirety of chapter 1 where Sophie spends her time coping from her isolation by talking to her hats.

Her mental stage is working around the loss of herself and the opportunities, time, and chances for herself. In some cases, thinking of life in a certain way can help minimize the suffering and pain that one endures if they don’t want to come to terms. However, there comes the fact that it is more damaging to the person the longer they continue with their ways. Sophie falls underneath this umbrella since her own coping is essentially one fitted to how she was originally responding to traumas as a child. She has become a reclusive, nervous wreck of a person (book canon) that refuses to leave home and works through executive dysfunction whenever she prompts herself to leave the house or do something outside of her schedule (house-work-sleep). This only happens once she is officially hired as an apprentice under Fanny and her sisters both leave for their apprenticeships. But, judging from what Martha tells her, Sophie’s tendency to wallow and hide didn’t suddenly appear. It’s been here and there that both sisters comment on it. Even when she tells herself that she should go, it’s up to her and she knows, it is then where she falls back to excuse certain things and continue only for the sake of someone needs to work.

And that itself is relatively childish. There are numerous gaps in her to understand herself and assess her own self that she tends to fall back into this box of where she’s been already used. To her, it’s easier to play upon the part assigned to her as opposed to seeking herself out and shedding off this role. It’s only until she is cursed beyond recognition that she, finally, goes out for her own and is remarkably accepting of the situation. (Which, really, speaks enough about Sophie’s mental health).

With all the emotional maturity and responsibility to help and guide others, however, there is freshness and uncomfortable feeling she carries when it comes to acknowledging her divided self. It is an untreated wound and unacknowledged creation made by her household. it is the ‘elephant in the room’ that even her sisters repeatedly tell her about (about her being exploited and being taken advantage of).

It could be simply said that Sophie, overall, confronts herself with over-simplifications of her own feelings and thoughts, despite showing intense and deep questioning and dislike. The actual her that wishes to speak cannot when the role she plays does not find need for it. With this in mind, this perpetuates frustrations and even more inclination to make skewed, if not worrisome, conclusions. If she could, she would rather split herself to play different roles just like what she does and ignore what is brewing inside her mind. Which is why, for verses including Sophie crossdressing (Simeon), or in disguise (ie: Myrtle in TW), this side of her is explored much more as for the fact she’s as willing and open to doing it

One of the best examples to elaborate on this Sophie’s confrontation of death and what she views it as. Taking into account from the previous HC post, there are two variations to how Sophie may view a particular topic (but end with the same results, which is her belief). The two accounts below carries the romanticize versus poison parts of herself.

To truly embrace of total removal of control, that was the final evidence needed to show that one was willing to submit their mortality in the hands of someone else.

A cold someone else, whose of the remains of all mankind, placid bones that caress against still-warm skin, cradling mortal’s falling form. Garments of black hug their rib cage, hollowed eyes gazing tenderly, they hold humanity and allow for the mortal to lay all weight and burdens into their hold. Bowing now from the dance of life, death takes the final lead in the danse macabre.

Sophie hopes at the time death greets her, when she submits herself unwillingly or willingly to the final number in their performance, that they were beautiful.

But, it was yet the step for that – as she never knew when it’d be and countless times, she could’ve. To when she would’ve been enveloped in unconditional acceptance, for the first time in her life, it was not yet time. For now, it was a long waltz with the grim reaper who waited for her.

Yet, the actress returns to form, facing the mirror once more as the curtains drew back on her neck.

ACT. ???? - SILVER STIGMATA.

Context: Sophie Hatter, after doing a night’s work as Simeon, is standing before her bathroom mirror, in a state of undress. Her mind right now is blurred between the current act of Simeon and the act of Sophie. She is looking over the parts of herself that she keeps hidden (her scars) and her own bareness has her examining herself. While lost in this space, she slowly succumbs to revisiting her true self, locked away in mind.

Part of her wants to laugh. How dare he have the audacity he had to think she’d be bothered by death? [...] Death was the only guarantee she had in her life besides her future as a failure.

DRABBLE RESPONSE TO @/diverse-hearts’ ASK.

Context: Sophie made a reckless decision during one of the Port Mafia’s events to take on an incoming threat that almost cost her life. Chuuya is reprimanding her while she’s laying out in a hospital, a place that is uncomfortable for her and reveals her usually hidden hostility and anger.

While elaborate in description and playing along with Sophie’s imagination (and thoughts), the ending results are still the same: death is the only other variable in her life promised to her. She may look at it lovingly and dream it or scoff and bitterly remark it as if ‘that’s how life is.’ Both still embrace it, which is reducing the actual gravity and weight of the situation of her almost dying and the thought of herself dying.

(For those curious: Sophie’s views on death for others is entirely different and she’s fearful of it for others. Relates back to both of her parents’ early death and her witnessing her father succumb to ailment while she spent most of her time caring for him.)

Anyways, that’s a lot for this one post ---!

#( in which we learn about the eldest ; headcanons )#death idealization tw#[ GOD DAMN FINALLY TUMBLR WORKS WITH ME ]#[ anyways. welcome 2 my shitshow of a post. ]

2 notes

·

View notes