#Mabuti Sardines

Text

PINHAIS: A Testimony of A Living History

(Translated from Maria Martinho's article, edited by S. M. Amamangpang)

A stone's thrown from the sea, Matosinhos is the epicenter of the canning industry to the north of Portugal. In that area alone, 52 fish factories were installed, today only two remain and one of them is PINHAIS. The company was founded in 1920 by António Rodrigues Pinto Pinhal together with his brother Manuel Rodrigues Pinto Pinhal, natives of Espinho, who initially dedicated themselves to salting fish in a small warehouse, and Luíz Alves da Silva Rios, who is believed to have launched the challenge to the two fishing brothers to set up a company dedicated to the manufacture of canned fish, to which Luíz de Sousa Ferreira later joined. With the construction of the factory, the company started to produce canned sardines, mackerel and horse mackerel in olive oil, spicy olive oil, tomato and spicy tomato sauce. “We still maintain the original process. From the treatment of the fish to the packaging, everything is done by hand,” guarantees António Pinhal, grandson of the founder and currently responsible for the family business that is in the third generation.

He was only eight when he had his first memory linked to Pinhais. Hand in hand with his father, he saw trawlers loaded with fish arriving at Matosinhos pier on a Saturday morning. “I always did that at the weekend, it was happy to see the seagulls approaching, it was a sign that there was a lot of fish”, he tells The Observer. Later, he was in his fourth year in Economics at the University of Porto when his father asked him to work with him. “My cousin was his right hand, but he got sick and called me. I went to the auction to buy the fish, did the commercial and export part. Only when my cousin passed away did I join the staffs of the company directly and, as a working student, I finished the Economics course at night. ”

For a decade, António was responsible for carefully choosing the raw materials for preserves, a function that allows him to distinguish the quality of a sardine with the naked eye today. “The sardine caught at four or five in the morning is better than the hake at midnight, I can see that from the eyes, the gills and the scales”, he says, adding that it was also on the wooden base of the trucks used to transport the baskets of fish that could take the real test of the nine. “I would take the sardine and throw it to the wood, if it jumped it had been caught in the morning, if it was quiet it was because it had been caught earlier.”

When he finished his Economics course, he already had several job offers, but his father said: either the bank or the factory. “The bug got into me and I ended up staying here. I don't know if I did it right or wrong, but I don't regret it.”

While most canning companies have industrialized over the years, Pinhais has decided to remain faithful to artisanal production, despite the various crises. “There was a Portuguese olive oil supplier that sold the product much cheaper and one day he asked my father if he didn't want to buy a car, which at that time cost about 100 contos, with the money he saved. My father did not have a license nor did he know how to drive, so he refused.” It was like this for four years, until it was discovered that this oil was adulterated. “The containers that other firms distributed to the United States were recalled and the canning industry crisis started there.”

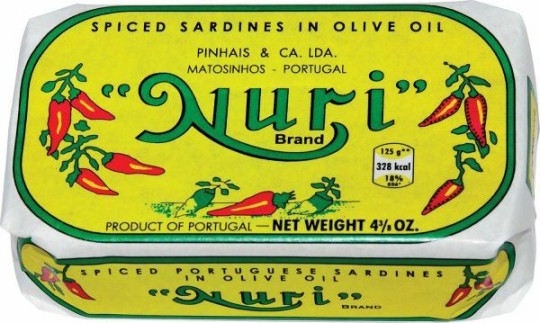

In 1935, Pinhais launched Nuri, a brand with the same products, but aimed at the international market. “One of the partners in the company was my uncle, a public relations person who spoke several languages. It was he who discovered the first international markets and when he went to Spain he met a very beautiful Spaniard named Nuri, that's how he decided to name the brand. ”

During the 40 years that he is at the helm of the canning industry, António Pinhal confesses that the most difficult moment was when the European Union's share of fishing emerged. The golden season in Matosinhos was from June to October, which forced the official to go buy fish in Sines, Peniche, Figueira da Foz, Spain or France. Nothing that would move him or make him lose his faith, after all the Pinhal family is deeply Catholic and in António's office are visible old cans, black and white photographs of the family, but also saints and candles.

“My father went to Mass twice a day and until three years ago we used to pray the rosary half an hour before the people left.” At 4:30 pm, someone put a cassette in the tape recorder and workers exchanged fish scissors for the rosary. “We stopped doing that when we hired people with other religions, it didn't make sense to be imposing that. It used to be different, people were more devout, especially when we talk about a fishing community. Times change and we have to accept those changes. ”

The fish arrives every morning through a special door, leaves the boxes and is immersed in an aluminum container in cold water and salt where the brine is given. “The large sardine is 40 minutes, the medium is 15 minutes, and the petinga, 5,” says António Pinhal. After this process, sardines, mackerel and horse mackerel are spread on large marble tables, where the head and the gut are removed with a small knife. "This is a normally mechanized process, but here we do it by hand to ensure that the gut comes out completely."

Headless and with a spine, the fish is placed one by one on a metal grid and dipped in a tank with cold water to remove the salt. The rooks loaded with fish are distributed in carts that enter a greenhouse at 100 degrees for 10 to 12 minutes. They come out of there hot and during the cooling process all the moisture and grease drain out. “Thus, both water and fat do not go into the can and oil, when added, turns yellow and not brown. This is one of our major differences from the competition,” explains António Pinhal.

It is only after this phase that the fish is placed in containers to then be cut by hand with scissors to fit in the can of preserves, which can then carry tomato sauce, cucumber, carrot or chilli pickles. In this assembly line, several employees dressed in white are seated in a row, from the cap to the wellies, passing through the waterproof apron. Many have their names written on the back and pillows to ensure comfort throughout the day.

Emília Vaz is in the section dedicated to homemade tomato sauce. She is 67 years old and is the oldest employee of Pinhais. She started at 18 and at the end of 2020, she will retire. With the reddish apron and the sweat on her forehead, she proudly shows the marks on her body that the years of work left him. “I've already cut myself on the toes with the cans and scalded my foot to make tomato sauce,” she says, adding that the factory is her second home and her colleagues are part of her family. She treats them by their first name and says she likes to teach those who arrive there for the first time. Among all, she is known as the “Emília da Afurada” (Emília, The Sharp). “In the past, I crossed the Douro in a small boat, but nowadays I take the bus to Boavista and then take the metro to get here.”

About 30,000 cans come out of Pinhais every day, essentially filled with sardines. There is no waste around here, proof of this is that the fish's head, tail and gut is sent to the flour industry to fertilize the soil and the remaining oil is supplied to the soap industry. On the mechanical mat, the cans stuffed with fish and other ingredients arrive in a veritable rain of Portuguese olive oil and are then closed by another machine. Still greasy, the closed can is washed in a tank with water at 100 degrees and sterilized for 60 minutes to eliminate any bacteria and will be packed by hand. Three months is the minimum time to stay in the warehouse to gain flavor, only after this period of maturation is the canned ready to go on its journey.

Célia Ferreira is responsible for the packaging department and in the 15-minute snack break she is the only one in the room to wrap cans of preserves. “I can eat at home,” she says, smiling, guaranteeing that she likes what she does. Her mother, aunts and cousins passed through Pinhais, so it would be almost inevitable for Célia to also work at the Matosinhos factory, where 1,200 cans per day pass through her hands. The natural employee of Leça da Palmeira walks surrounded by cards and packages painted in yellow, green, red or blue and knows the destination of each one by heart. "These go to Australia, those to the United States and those to the Czech Republic.

In 2016, the Pinhal family sold its stocks to an Austrian agent, the current owner of the brand. “It was a decision motivated by the fishing crisis, there were no orders, we lacked liquidity and we thought it was necessary to take this step. He is a trustworthy person, he has worked with us since 1985, he belongs to a family business connected to cereals. At one time, he was our best customer, he represented more than 70% of our exports, and he became the only way to save this firm,” recalls António Pinhal. Despite the change, everything seems to have remained. “The only premise was to leave everything as it is.” Currently, Pinhais exports 90% of its production to countries such as Austria, the United States, the Philippines, Denmark or France. Here, the points of sale are limited to gourmet stores. “Quantity is not quality. We bet on quality, while in large stores we buy a can of sardines at 0.90 cents, ours costs € 2.50. The labor is very expensive, we work with 14 or 15 stages, the other factories have only three,” justifies António Pinhal.

Extending the range of products is not part of the brand's plans, which work on original marble tables from 1920 and see their work space limited to small fish. However, there is a need to bring something new to the market, so next year, Pinhais will use leftover sardines to market patês. The online store was launched just in time for the pandemic and in the summer of 2021 a live museum is expected on the factory premises, a project that has lived in the drawer for several years and bureaucracy has delayed. “We want to make it known what the tradition of the canning industry was, showing, at the same time, how we work.”

António Pinhal is not afraid of the future and says that only the pandemic forced small changes in the company, such as the acrylics arranged among the workers, a laboratory converted into a quarantine room and more mechanized transport processes. The grandson of the founder of Pinhais eats preserves religiously every Friday at lunch. “Canning tins are normally six years old as an expiration date, but my father always preferred old ones that were 15 or 20 years old. Every Friday at lunch he opens an old can, watched, smelled and asked me to eat a piece. After five minutes, if I didn't feel bad, I would eat it. It was your guinea pig and I thought it was funny. ”

Source:

(https://observador.pt/2020/09/13/conservas-pinhais-a-fabrica-onde-se-rezava-o-terco-e-hoje-se-canta-o-fado-enquanto-se-enchem-latas/)

#Pinhais#Matosinhos#Portugal#sardines#sardinha#sardinas#sardinia#Nuri Sardines#Mabuti Sardines#Rios Sardines#artisanal#traditional

8 notes

·

View notes