#Quentin Iverson

Video

River Crossing by Jeff Goldberg

#@jeffagoldberg#Chris Petersen#Equestrian#Horse#Jeff Goldberg Photography#Quentin Iverson#River#Sombrero Ranches#Splash#Western#Western Art#flickr

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I was so shocked by her decision to not go to the funeral when I read [the script]," Gold said. She continued, "Not in a bad way. I just thought, 'Wow, that’s bold.' But I think now she seems more done than she ever has — and she’s been pretty done. She’s done being collateral damage, and I think we’re really getting to see her terrified, maybe dealing with her own complicity and getting out of Dodge — and she’s not going to show up for him. She’s putting her kids [Sophie, played by Swayam Bhatia, and Iverson, played by Quentin Morales] and their safety first."

maybe dealing with her own complicity ,, natalie your mind

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Galeb Bazory - Evaluation by Jara Drory

During Quentin King’s reign, Galeb Bazory was always above reproach, performing every task assigned to him without batting an eye. He is the consummate tool for doing dirty work, as he is cold and efficient. I won’t even begin to tell you how many thin-blooded, Anarchs or dissidents he has faced ( and defeated ). Such overwhelming loyalty to your predecessor would suggest that he be sidelined or even removed. Nevertheless, I urge you not to rush down this path. On the contrary, keeping Galeb Bazory as close to you as possible seems to me the wisest thing to do. Indeed, his loyalty was not to Quentin King but to the role of the Prince, and today that is you, Ms. Iverson. Galeb Bazory could quickly become one of your best assets.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this day in Wikipedia: Sunday, 25th February

Welcome, ողջու՜յն (voġčuyn), ようこそ (yōkoso), selamat datang 🤗

What does @Wikipedia say about 25th February through the years 🏛️📜🗓️?

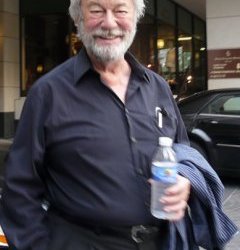

25th February 2023 🗓️ : Death - Gordon Pinsent

Gordon Pinsent, Canadian actor, director and screenwriter (b. 1930)

"Gordon Edward Pinsent (July 12, 1930 – February 25, 2023) was a Canadian actor, writer, director, and singer. He was known for his roles in numerous productions, including Away from Her, The Rowdyman, John and the Missus, A Gift to Last, Due South, The Red Green Show, and Quentin Durgens, M.P. He..."

Image licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0? by christopherharte

25th February 2017 🗓️ : Death - Bill Paxton

Bill Paxton, American actor and filmmaker (b. 1955)

"William Paxton (May 17, 1955 – February 25, 2017) was an American actor and filmmaker. He starred in films such as Aliens (1986), Near Dark (1987), Tombstone (1993), True Lies (1994), Apollo 13 (1995), Twister (1996), Titanic (1997), Mighty Joe Young (1998), and A Simple Plan (1998). He had..."

Image licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0? by Gage Skidmore

25th February 2012 🗓️ : Death - Louisiana Red

Louisiana Red, American singer-songwriter and guitarist (b. 1932)

"Iverson Minter (March 23, 1932 – February 25, 2012), known as Louisiana Red, was an American blues guitarist, harmonica player, and singer, who recorded more than 50 albums. A master of slide guitar, he played both traditional acoustic and urban electric styles, with lyrics both honest and often..."

Image licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0? by Hreinn Gudlaugsson

25th February 1974 🗓️ : Birth - Dominic Raab

Dominic Raab, English politician; First Secretary of State and Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs

"Dominic Rennie Raab (; born 25 February 1974) is a British Conservative Party politician who has been Member of Parliament (MP) for Esher and Walton since 2010. From 2019 to 2023, with a brief period out of office during the Truss premiership, Raab was deputy to prime ministers Boris Johnson and..."

Image licensed under CC BY 3.0? by Richard Townshend

25th February 1924 🗓️ : Birth - Hugh Huxley

Hugh Huxley, English-American biologist and academic (d. 2013)

"Hugh Esmor Huxley MBE FRS (25 February 1924 – 25 July 2013) was a British molecular biologist who made important discoveries in the physiology of muscle. He was a graduate in physics from Christ's College, Cambridge. However, his education was interrupted for five years by the Second World War,..."

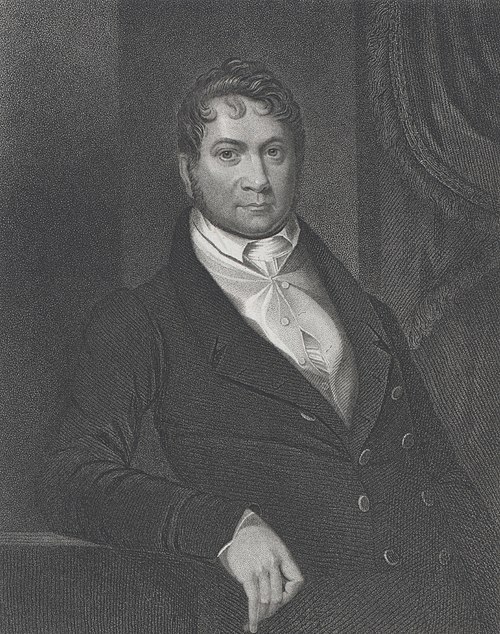

25th February 1822 🗓️ : Death - William Pinkney

William Pinkney, American politician and diplomat, 7th United States Attorney General (b. 1764)

"William Pinkney (March 17, 1764 – February 25, 1822) was an American statesman and diplomat, and was appointed the seventh U.S. Attorney General by President James Madison...."

Image by Scan by NYPL

25th February 🗓️ : Holiday - Christian feast days: February 25 (Eastern Orthodox liturgics)

"February 24 - Eastern Orthodox liturgical calendar - February 26 All fixed commemorations below are observed on March 10 (March 9 on leap years) by Eastern Orthodox Churches on the Old Calendar.For February 25th, Orthodox Churches on the Old Calendar commemorate the Saints listed on February 12...."

Image by njk92

0 notes

Text

:)

Credit to: @/jeremystrongupdates + @/quentinmorales

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

3x08 Chiantishire (1/2)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snake Charmer

I grabbed my sneakers and ball from the backseat of my car. As I stepped onto the basketball court, the palm of a stranger’s hand suddenly hit my chest before my foot crossed the threshold of the out-of-bounds line, as if to protect me from stepping into molten lava. It was in fact hallowed ground he was preparing me to enter. “I don’t want to mess up your day, but Kobe Bryant died.” The words did not register. He must have meant to say Bill Russell or Magic Johnson or some other retired player, up in years or immunocompromised. My heart sank as the words did. Seemingly coordinated with the stranger’s preparatory address, my phone began to shriek. I shared basketball, above most else, with my closest friends, and for those of my friends “not into sports,” they knew I was and that I was probably the one person in their lives that could explain why their instagram and twitter timelines had been commandeered by the news of Bryant’s death. I sat on the court and texted friends I hadn’t spoken with in years. I mentally ran through all of the Lakers fans in my life, like someone tallying loved ones near the epicenter of an earthquake or tsunami.

The surprises continued. My uncle Kenny called me. Kenny, like most of the men in my life, does not make calls. When I see Kenny during the holidays we do not hug or catch up with small talk. Me and Kenny speak solely in sports. “How are the Cowboys doing?” translates to how are you doing? On this occasion Kenny did not resort to code. “Are you okay?” Kenny asked with a tone of genuine concern in his voice. Strangely, I was not. Stepping out of my body momentarily, I watched myself frantically text friends and scour the internet for updates with large tears welling up in my eyes. Importantly, next to me, five or so other guys on the basketball court were doing the exact same thing. I was dumbfounded, and even a little amused that it was Kobe Bryant, of all people, that elicited this reaction from me. As a basketball fan I loved Kobe Bryant as a player, but I didn’t love him. I loved Kobe the way the world loves the Dalai Lama. Kobe was that inhuman child/god/king we watched grow up, do great exploits, and whose often trite proverbs of ostensible wisdom we warily entertained. His sudden and violent death brought into swift focus that, while famous for almost my entire life, I took Kobe for granted.

Kobe Bryant was the first of us to realize: the camera is always on. In the days and weeks following Kobe’s death I found myself pulling up old games on youtube and having them on in the background while I worked. I was surprised how many of the beats–a certain sequence of plays, a specific call by an announcer–I remembered, like I was watching reruns or listening to a throwback radio station. As much as The Fresh Prince or Martin or Seinfeld, Kobe Bryant was TV. Mostly to my frustration, as someone who ineffectually rooted against the Lakers, Kobe Bryant was always on my screen. Undoubtedly, a cloud hangs over everything related to Bryant now in light of his death, but rewatching games from the 2000 finals, in which Bryant’s Lakers bested the Reggie Miller/Jalen Rose led Pacers, I was reminded of how much uneasiness and sadness I felt for Kobe Bryant watching him even as a teenage admirer. After every exceptional defensive play, flashy pass, or difficult made shot, Bryant made sure the camera saw the fiery glint in his eyes, the licking of his lips, the exaggerated clinching of his jaw.

Even more so than the NBA’s previous generation of celebrities–Bird, Magic, Jordan–Kobe Bryant seemed to be the first superstar to internalize that basketball was a performance: a movie backed by a John Tesh score, or more specifically, a loosely scripted 24-7 reality show complete with story arcs, heroes, villains, close-ups, and backstabbing confessions. Bryant perpetually signalled: to the camera, to the fans, to his haters, to his teammates, that he possessed the most passion, that he outworked everyone, and that he would stop at nothing to be the best. By all accounts this was all true. But we knew it less because it was true and more because Kobe wanted us to know. Even as a youngster I found his thirst obnoxious.

Kobe was desperate, but he was also just ahead of the curve. Kobe Bryant proudly admitted to not having a social life, and almost a decade before Russell Westbrook said it, Bryant proclaimed that “Spalding was his only friend;” a both sad and sobering admission for any would-be competitors tasked with defeating Bryant on the court. Bryant’s performative work, that now permeates and characterizes most of millennial culture, predated social media. The author Touré in his book, I Would Die 4U, contends that despite being a baby boomer, Prince was the quintessential GenX celebrity, whose music perfectly tapped into that younger generation’s disaffected, countercultural ethos. Born in 1978, Bryant technically resides in GenX. The intense outpouring from all corners of the digital world over Bryant’s death stems from the fact that he was truly the first millennial celebrity.

For Bryant, fame came before success. As the photogenic rookie for the Lakers, Bryant had cameos on sitcoms, graced the cover of every teen magazine, took Brandy to the prom, put out a rap album, and pitched every soda and sneaker Madison Avenue could throw at him. But like an inflated college application, Bryant’s extracurriculars read as contrivances. Bryant was named a starter in the 1998 All-Star game, an honor voted on by the fans, meanwhile he wasn’t even a starter on his own team. To suspicious observers, Bryant was an industry plant; the antidote to the fearful influx of hyper-black, hip hop culture embodied in players like Allen Iverson or Latrell Spreewell; a basketball and marketing robot with a pearly white smile, that spoke multiple languages, and would pick up where Michael Jordan left off; ushering the NBA to unprecedented commercial heights.

Despite his superficial charm, Kobe Bryant’s lack of genuine personality proved off-putting, almost creepy. Although possessing a similarly shimmering smile, everyone knew that the real Michael Jordan chomped on cigars, pounded tequila, gambled through the night, and did not actually hang out with Bugs Bunny while wearing Hanes tighty-whities. We acknowledged humanity, healthiness even, in this contradiction. For Bryant’s generation of sports superstars, the public and private arrived flattened. A sports prodigy, a la Tiger Woods, Bryant’s lone-gun, misanthropic persona emerged as a defense against the alienation he felt from his teammates and colleagues around the league, those that did not share his cloistered upbringing. Bryant’s longtime teammate and consummate foil, Shaquille O’Neal, had the nickname, Superman. Despite his titanic presence and supernatural physical gifts, O’Neal epitomized the terrestrial; always joking, dancing; embedded in pop culture; a true man of the people. The true Kryptonian was always Bryant.

As an ignorant seventeen year-old, my initial reaction in 2004 to the accusations of rape against Bryant was amused shock. “Kobe Bryant has sex?!” In 2004, I, like many, put Kobe on the shelf. Less out of a desire to proactively make any bold gestures on behalf of women, but more out of petty schadenfreude. As stated before, I respected the talent, but I was not really a Kobe fan. I always rooted for the underdog, and Bryant was anything but. To the contrary, everything about Bryant was an assault on the concept of the underdog, the diamond in the rough, the idea that anyone, despite their humble or downright degraded beginnings, could rise to excellence. Bryant was born and bread to be great. Sadly, I took grim pleasure in seeing the NBA’s posterboy–the prototype of black celebrity respectability–revealed as the actual embodiment of the entitled, toxically masculine, and sexually predatory stereotype of the black athlete.

Bryant lost endorsements. Nike released the Huarache 2K4, an all-time great basketball shoe originally designed to be Bryant’s first signature release with the brand, as simply a stand-alone product. The Lakers shopped Bryant around for possible trades. Like Sampson sheared and stripped of his powers, Bryant’s hairline appeared to recede, he cut off his signature fro, and he began shaving his head closer and closer. Bryant changed his number from 8 to 24 as one now changes their Instagram or Twitter handle to represent a break from the past. Like a biblical character after a traumatic or transformative event, like Abram becoming Abraham, or Saul becoming Paul, Bryant adopted the moniker of the Black Mamba. He resigned to allow the sorting hat to place him in his rightful house of Slytherin, and embraced the duplicitous snake that many already viewed him to be. Somewhat strangely, the Black Mamba was the assassin code name of the main character in Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill, who in the film is left for dead, and out for revenge. Did Bryant see himself as this woman wronged, or as the titular character, Bill, contently awaiting his deserved day of judgement. Knowing Bryant, he probably saw himself as both.

In the myth of Hercules (not the Disney version) the famous god-man kills his wife and kids in a fit of hysteria inflicted by a vengeful Hera. If we imagine that the mythical figures of today were really just the celebrities and aristocrats of past millennia who had control over the pen of history and whose carnal tales swelled into sacred gospel; the fits of rage and mania brought on by the devil or hades or a poison arrow, were really the Chappaquiddicks, Vegas hotel rooms, and dog fighting compounds of their time; times when our heroes unequivocally and inexcusably committed evil. If Hercules was in fact a real man of some importance to his time–the son of a dignitary–that unfathomably killed his wife and kids, it follows that instead of being sentenced to death or some other fate reserved for the criminal commoner, that he would be given some lesser sentence and a chance–albeit slim–of redemption. Hercules is banished by the gods to serve an insignificant king and accomplish the arduous good works assigned to him as a means of atonement; the great works–slaying the nine-headed hydra, retrieving cerberus –that ultimately generate his immortal legend.

Bryant’s post rape case/post Shaquille O’Neal years with the Lakers mirror this herculean restitution. Despite years on center stage, the Lakers, like Bryant, were similarly in their nadir, and would spend the middle of the aughts in basketball purgatory. Bryant was no longer primetime television. What happens to a pop-star when no one is watching? Surprisingly, Kobe Bryant kept performing, and at higher heights. Bryant was doing his best work while no one was watching. I remember walking through the door of my college dorm on a non-descript spring day. My roommate, Bryun, yelled at me with no context, “8 1 P O I N T S !” Kobe Bryant’s 81 point game may lay claim as the first social media sports moment. Less because no other great sports moments had occurred between 2004, when facebook emerged, and his scoring explosion in 2006, but because very few people watched that midseason contest between two mediocre teams live. It arrived to everyone, like myself, after the fact.

During a recent lecture, artist Dave McKenzie, when answering a very banal question during a post lecture q&a, about his long term goals as an artist, answered soberingly, “I’m just trying to get through this life and do the least amount of harm.” While we all hope to navigate this life without hurting others, most, if not all of us, will in some way. While we can and must continue to interrogate why powerful (or at least useful to the actual powerful) men like Kobe Bryant seemingly evade the full reckoning of their actions, we must acknowledge that Bryant became something of a patron saint to those who for whatever reason found themselves on the wrong side of right. Maybe they were the underprivileged black and brown boys and girls in over-policed neighborhoods of LA where Bryant played for 20 years. Perhaps they were not pure victims but made some questionable choices and found themselves caught in the system. Or maybe it was the newly divorced father attempting to win back the respect of his kids after breaking apart his family due to his own indiscretions. Kobe Bryant in this second half of his career, culminating in back to back championships, provided a picture of how one climbs back from the depths of hell, even if they were the one that put themself there. This explains the irrationality of Kobe fans, who defended him in everything, and straight-faced spoke his name in the same breath as Michael Jordan, despite honestly being in a class below. For them, Kobe was bigger than basketball, and while many fans share a vicarious relationship with their sports heroes or teams, Bryant’s winning was more profoundly linked to his fans’ sense of self-worth.

Precocity embodied, Bryant arrived in the NBA a generation too soon. As the son of a former player, singularly focused on professionalizing at a young age, even foregoing college at a time when that was still a rarity, Bryant was an alien compared to most players of his generation. The trajectory of players today more resembles Bryant’s. Gone are the days of Dennis Rodman or Scottie Pippen or Steve Nash picking up basketball late, or being undiscovered and surreptitiously landing on a small college team, eventually catching the eye of the larger basketball world. Now, professional basketball starts disturbingly early. Prospects like Zion Williamson have millions of Instagram followers in high school. Second generation pros are commonplace – Steph, Klay, Kyrie, Devin Booker, Andrew Wiggins, Domantas Sabonis, Austin Rivers, Tim Hardaway Jr., Glenn Robinson III, and so on. Bryant was the cautionary tale, a sage mentor, and ultimately an icon to the generation of players succeeding Bryant, who like him, entered the spotlight and scrutiny of an increasingly voracious sports machine as children. Thanks in part to witnessing the triumphs and travails of Bryant, today’s young superstars arrive to the league encoded with the understanding that the fans, the media, the sports industry writ large, wait with baited breath for them to fuck up off the court as much as they do a spectacular play in the game. To these various stakeholders, it’s all good entertainment.

[A bit of a tangent] As the coronavirus began to ravage New Orleans, in particular the homeless and already vulnerable of the city, I had a group of friends, more acquaintances, who took it upon themselves to collect donations, buy groceries, prepare and ultimately hand out meals to the large number of homeless people mostly living under the I-10 overpass downtown. As a naturally cynical person, I immediately questioned the motivations. All of those same homeless people were living under the overpass before coronavirus, where was this energy then? One friend involved with this effort confided that she was incredibly anxiety stricken in all of this, and that this “project” was taking her mind off things. I chafed at the phrasing of feeding the homeless as a “project.” Additionally, daily I would scroll through the Instagram feeds of those helping and see pics of cute hipsters in masks and gloves and in grungy, rugged, but still impossibly chic outfits posing in Power Ranger formations in front of their rusted Ford Ranger filled with grocery bags to distribute. A masterclass in virtue signalling, the narcissism of it all polluted the entire endeavor for me. When I asked a trusted voice why this all rubbed me the wrong way, this person replied curtly, “What does it matter why or how they do it? They’re doing a good thing.”

Kobe did not simply embrace this role of elder-statesman to the succeeding generation, he courted it, campaigned for this mantle as aggressively as he once sought championships. Lacking confidence in the intellect of the public to make their own conjectures of how Bryant resurrected his career, he rebranded himself a self-improvement life-couch, and proselytized his “Mamba Mentality,” even staging a parody Tony Robbins style conference as a Nike commercial. He collected young promising players to mentor like Leonardo DiCaprio collects young blonde models to date. Gossipy whispers swirled every offseason, “Kobes working with Kawhi.” or “Watch out for Jason Tatum this year; he spent the summer training with Kobe.” All of Kobe’s newfound openhandedness seemed spiked with self-aggrandizement. Opting to be the mentor of the next generation ensured that the success of future stars led back to him, and that he would be relevant and sought after long after his retirement.

Whatever the subconscious or even conscious motivations behind Bryant’s mentorship, his movie Dear Basketball, or his show Detail–in which he broke down the games of basketball players across levels and leagues, treating women’s college basketball standout Sabrina Ionescu with the same care and reverence as NBA star James Harden–the result was education, service, stewardship, and love for the game of basketball.

I started writing this soon after Bryant’s death but struggled to synthesize an ultimate point. In the end I am not sure I have one, just that Kobe Bryant, much to my surprise was a figure of enough complexity and enduring relevance to require re-interrogation. In hindsight, I needed to watch The Last Dance; the 10 part Michael Jordan re-coronation. In 2009 newly elected President Barack Obama, after stumbling over the oath of office during the freezing January inauguration, retook the oath the next day in a private ceremony just in case any of his political enemies, or the fomenting alt right with its myriad factions–from the conspiratorial to the downright racist–tried to invalidate his presidency. While trivial in comparison, Jordan, with The Last Dance is attempting desperately to reconfirm that he is the greatest basketball player of all-time, something only a few lunatics question. While the actual game footage is a wonder and leaves no doubt of Jordan’s basketball supremacy, the final tally of this hagiographic enterprise may result in a net loss for Jordan. Jordan, like a 19th century robber baron, seems to genuinely believe that his misanthropy, arrogance, condescension, usury, brutality, workaholism, and myopic focus on basketball, and consummate self-centeredness were all justified, required even, to win. To win what? Championships? With sports leagues and public officials debating when and if sports can and should come back amidst a virus with devastating life or death stakes, sports and success within them feel quite trivial and quaint at the moment.

Having won at everything in life, sitting in his palatial mansion, sipping impossibly overpriced scotch, Jordan does not seem fulfilled. He is Ebenezer Scrooge. Unfortunately, it is not Christmas, and no ghosts of introspection are visiting Jordan, only a camera crew determined to retell the gospel of Jordan with a few non-canonical details sprinkled in for flavor. I am reminded of a line in Pat Conroy’s My Losing Season, an autobiographical account of his college basketball days at The Citadel. After a storied career, Conroy’s senior season is a disaster (hence the title). In it he says no one ever learned anything by winning. The inference is that, while winning is great, the actual growth occurs before, in the losing. Jordan in The Last Dance is the ghastly personification of “never losing. Like Bane before breaking Batman’s back, “Victory has defeated you.” With an unimpeachable resumé, Jordan was never required to question his actions or behaviors towards his teammates and competitors. Worshiped unwaveringly by all, Jordan never felt the need to give anything back to the game or to the communities that supported him.

While never verbally conceding, Bryant seemed to embrace being the loser. Bryant realized early, perhaps as early as Colorado, that he was never going to be as beloved as Jordan. He began planning early for a life outside of basketball. He started a production company. He braved eye-rolls for the n-teenth time when he proclaimed that he was going to be a “storyteller.” Beyond a cliché adage, Bryant became a “family man,” and focused on this part of his life with the same ferocity that he once attacked the basket. Despite braving turmoil very publicly as a young couple, the bond between Bryant and his wife Vanesa appeared, at least on the outside, genuine. They welcomed their newest daughter, Capri, just 7 months before his death. While no less ambitious or busy in retirement, the Bryant who once wore his insecurity and desperation on his sweaty armband, strangely appeared content, happy. The guy who once proudly proclaimed “Spalding his only friend” relented to a verdant life with others.

While undoubtedly compounded by the tragic and sudden nature of his death, the truly astounding outpouring for Kobe–murals the world over, calf-length tattoos, millions of twitter handle re-namings–stands as an accomplishment, or better said, an acknowledgement that “better” athletes like Jordan or LeBron or Tiger or Brady will probably never receive. He wasn’t the best of us, and in many ways we loved him even more because of that. Before The Last Dance we got a preview of the more candid Michael Jordan during Kobe Bryant’s memorial, where Michael, who unbeknownst to us all was a confidant of Bryant’s, admitted that Kobe made him want to be a better father, a better person. In the end even the GOAT was a disciple of the Mamba. It’s only right that the first millennial superstar gained the biggest following.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spoilers Below

INTRODUCTION

Succession Season Three Episode Nine, “All the Bells Say,” directed by Mark Mylod, ends with Logan Roy (Brian Cox) “winning” but leaving his children with Lady Caroline Collingwood (Harriet Walter) in the dust. Logan begins to sell Waystar RoyCo to Lukas Matsson (Alexander Skarsgard) for a five-billion-dollar settlement. Now Siobhan “Shiv” Roy (Sarah Snook), Roman Roy (Kieran Culkin), and Kendall Roy (Jeremy Strong) won’t ever be able to take control of the company. The three siblings come up with a plan to stop Logan from selling the company. Tom Wabsgans (Matthew Mcfayden) betrays Shiv to gain status. Tom officially “trades” Shiv for Greg Hirsch (Nicholas Braun).

TWO GODS & THE GOLDEN PARACHUTE

Logan has grown tired of conquering the business world but can’t bow out without a significant win. The beginning of “All the Bells Say” foretells the media giant selling Waystar RoyCo. Logan reads the storybook Goodbye Mog to preteen grandson Iverson Roy (Quentin Morales). The storybook is all about a cat named Mog who’s “dead tired” and sleeps forever. Logan also feels dead tired and no longer completely understands the media landscape. When he meets with Lukas, the GoJo Tech God mentions how Logan is too tired to lead Waystar RoyCo into the twenty-first century. Lukas leaves Logan an opening to bow out without losing face or leaving any money on the table.

The introductory talk feels like an actual meeting of equals. Both Lukas and Logan are Gods who exist on a different plane from the rest of us mortals. Lukas doesn’t comment on things with his dry sense of humor. Logan doesn’t put on the charming old man act, and he doesn’t rely on Roman to do the heavy lifting. But, on the other hand, Lukas likes how Logan jumps right into business because he gets bored quickly. The two CEOs both agree that everything bores them except for business.

Logan and Lukas walk to the outside patio furniture faster than Roman, even though his father is an eighty-year-old man with health issues. Lukas straightforwardly explains all of Waystar RoyCo’s problems, starting with the fact that Logan can’t turn it into a tech company because of his age. Logan pushes back but reveals that he does not love the American business world anymore.

When Lukas proposes taking over Waystar RoyCo, Logan doesn’t storm off. Instead, Logan questions Lukas with, “Are you fucking serious?” Lukas promises that he doesn’t want to make the other CEO “small” and proposes excellent parameters.

Lukas reads how conflicted Logan feels about the proposed buyout, including how it would rob his children of the CEO spot. Instead, Lukas promises to make Roman the center of integrating the two companies and give all Waystar RoyCo’s top brass a chance.

After Logan says no, the two gods start speaking in code. The two men stare into each other’s eyes as they plan to “switch assets.” Lukas gestures with his eyes at Roman, who’s anxiously watching the conversation. Logan orders Roman back to Caroline’s wedding. Logan wants to talk about selling Waystar RoyCo without Roman present. All he cares about is “winning,” a.k.a. piles of money that he will never be able to spend.

SIBLINGS UNITE

Kendall, Shiv, and Roman unite against their father. After Kendall confesses to drowning the young waiter accidentally, he shares an emotional moment with his siblings. Shiv and Roman awkwardly comfort their brother with pats on the back and jokes about how they have all killed people. When Shiv confirms that their father plans to sell Waystar RoyCo, giving away control of the board, she orders a car for all three of them.

Before entering their car, Shiv tells her brothers they need to stop the deal. The Roy siblings drive through the beautiful Italian countryside, hatching a plan. Roman tries to stand up for Logan because he has been working closely with him. Shiv points out that their father selling to Lukas means he doesn’t think that any of them should run Waystar RoyCo. Logan believes all his children are mentally weak and wants to leave the company to another God who’s proven his business genius.

Roman questions if they can even legally stop Logan. Kendall explains a change of board control “needs a supermajority in the holding company. Mom got that for us in the divorce.” The sale requires their approval. Roman is still on the rocks because he thinks the deal with Lukas may leave him a chance to gain some power.

Shiv and Kendall team up to explain to Roman that Logan will never back him. Logans thinks his youngest son is a pervert who will leave Waystar RoyCo vulnerable to attack. Roman reluctantly agrees to help them push their father out of the company.

Kendall and Shiv plan to use Logan’s health issues and their refusal to back the sale to blackmail him into stepping down. All three siblings will rule Waystar RoyCo equally.

FAILURE TO LAUNCH

Shiv proposes that the three of them fight for complete control of Waystar RoyCo, which both Kendall and Roman think will be fun. Even Roman admits they will make a good team. Sadly, the coup doesn’t work because Tom betrays Shiv by snitching to Logan. Logan uses the knowledge in his negotiations with his second ex-wife, a.k.a. their mother. Caroline agrees to take out the clause in their divorce settlement that gives her children veto power in exchange for the London apartment.

Tom wants to be the more dominant one in the marriage for once. Tom leaves Shiv in the cold without a parachute. However, he protects Greg by giving him a minor role at the top of the new GoJo Waystar RoyCo company.

LAST THOUGHTS

How will the Roy sibling survive without Waystar RoyCo? Let us know your thoughts on Succession Season Three below in the comments.

#succession season 3#hbo succession#tv recap#tv blogger#awards radar#shiv roy#logan roy#kendall roy#roman roy#lukas matsson#caroline collingwood#greg hirsch#waystar royco

0 notes

Text

SUMMARY

Harry Moseby (Gene Hackman) is a retired professional football player now working as a private investigator in Los Angeles. He discovers that his wife Ellen (Susan Clark) is having an affair with a man named Marty Heller (Harris Yulin).

Aging actress Arlene Iverson (Janet Ward) hires Harry to find her 16-year-old daughter Delly Grastner (Melanie Griffith). Arlene’s only source of income is her daughter’s trust fund, but it requires Delly to be living with her. Arlene gives Harry the name of one of Delly’s friends in Los Angeles, a mechanic called Quentin (James Woods). Quentin tells Harry that he last saw Delly at a New Mexico film location, where she started flirting with one of Arlene’s old flames, stuntman Marv Ellman (Anthony Costello). Harry realizes that the injuries to Quentin’s face are from fighting the stuntman and sympathizes with his bitterness towards Delly. He travels to the film location and talks to Marv and stunt coordinator, Joey Ziegler (Edward Binns). Before returning to Los Angeles, Harry is surprised to see Quentin working on Marv’s stunt plane.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Harry suspects that Delly may be trying to seduce her mother’s ex-lovers and travels to the Florida Keys, where her stepfather Tom Iverson (John Crawford) lives. In Florida, Harry finds Delly staying with Tom and a woman named Paula (Jennifer Warren). Harry, Paula, and Delly take a boat trip to go swimming, but Delly becomes distraught when she finds the submerged wreckage of a small plane with the decomposing body of the pilot inside. Paula marks the spot with a buoy, and when they return to shore, she appears to report the find to the Coast Guard.

Harry persuades Delly to return to her mother in California. After he drops her off at her California home, he still is uneasy about the case, but focuses on patching up his own marriage. He tells his wife he will give up the agency, something she has wanted him to do for a long time, but then he learns that Delly has been killed in a car accident on the set of a movie.

Harry questions the driver of the car, Joey, who was injured. Joey lets him view footage of the crash, which raises Harry’s suspicions about Quentin the mechanic. He goes to the home of Arlene Iverson and finds her drunk by the pool, not particularly grief-stricken over the death of her daughter. Arlene now stands to inherit her daughter’s wealth. Harry tracks down Quentin, who denies being the killer, but tells him that Marv Ellman was the dead pilot in the plane and that Ellman was involved in smuggling. Quentin manages to escape before Harry can learn more.

Harry returns to Florida, where he finds the body of Quentin the mechanic floating in Tom’s dolphin pen. Harry accuses Tom of the murder, they fight, and Tom is knocked unconscious. Paula admits she did not report the dead body in the plane because the aircraft contained a valuable sculpture that they were smuggling piecemeal to the United States. Harry and Paula set off to retrieve the sculpture. While Paula is diving, a seaplane arrives and the pilot strafes the boat, machine-gunning Harry in the leg. The seaplane lands on the ocean, but when the pilot sees Paula surface with the sculpture, he charges the plane at her and she is killed. The impact of the pontoons on the surfaced sculpture shatters the seaplane, and as the cockpit submerges into the ocean, Harry is able to see through the glass window beneath his boat that the drowning pilot is Joey Ziegler. Harry unsuccessfully tries to steer the boat which is now travelling in circles.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

DEVELOPMENT

One of the first things that Arthur Penn did when he inherited the Alan Sharp script The Dark Tower from the director-producer team of Sydney Pollack and Mark Rydell was to change the title to Night Moves (1975). Sharp’s script had been named as a coy reference to the Universal Pictures executive building, known in the industry as The Black Tower; in reworking Sharp’s original scenario, a mystery set between the strangely complementary milieu of movie-making and artifact smuggling, was to emphasize a telling bit of business in the script about chess playing and the inability (or disability) of its detective hero in seeing the move he should have made.

Penn had absented himself from narrative filmmaking for several years, hot off the success of Bonnie & Clyde (1967) and Little Big Man (1970). (In the interim, he helmed a segment of the 1973 Olympics documentary, Visions of Eight, filmed in the aftermath of the massacre of Israeli athletes by Arab terrorists during the 1972 summer games in Munich.) Night Moves represented a departure from his earlier focus on lawbreakers – the folk heroes of the Left-Handed Gun (1958) and Bonnie & Clyde, the convict-on-the-run in The Chase (1966), the Turkey Day litterer of Alice’s Restaurant (1969) – and focused instead on a tired Los Angeles PI (Gene Hackman) juggling professional and personal mysteries.

During the pre-production stage Penn and his screenwriter Alan Sharp disagreed on several aspects of the story, as directors and screenwriters are apt to do. While they managed to maintain an uneasy spirit of compromise – Penn gave way to Sharp on a number of points – the screenwriter later criticized Penn for this apparent failing. They met halfway on the final ambiguous scene: Penn had wanted Harry to be offered a glimmer of a chance to reunite with his wife, while Sharp thought Paula should survive to start a new life with Harry.

They did agree wholeheartedly on the choice of Gene Hackman for their hero. Penn knew that Hackman preferred to work intuitively rather than intellectually. Hackman’s usual method was to read a script twice, then put it down for a while, so he could absorb the words and allow ideas to filter up. He could memorize pages of dialogue before going on the set, and when he arrived he did so without a strong preconceived notion of how the performance would evolve. But on this film Penn rehearsed his actors for ten days prior to filming, during which time dialogue was reworked, after much input from the actors themselves.

Sharp found that Hackman was a wonderfully skilled actor who seemed able to make very complex perceptions without having to verbalize or intellectualize them.’ There was, perhaps, a note of personal conviction when Hackman says in a scene in which he comforts a tearful Melanie Griffith, ‘It’s bad when you’re sixteen but when you’re forty, it’s no better.’ Sharp observed, ‘When I saw that rendition I was so astonished. There was that personal content which I found worked successfully.’

The rehearsal period allowed Penn to indulge his personal method of digging into the personal life of whichever actor he’s working with, and seeing if he could unearth something there for the actor to draw on. The director was aware that Hackman was undergoing personal problems and that this mirrored the plight of his role. Like the fictional private eye, Hackman was torn between the demands of his job and the demands of his family.

After it was finished, at a cost of $4 million, Warner Brothers seemed to be unsure of quite how to market the film. Penn had produced a dark and complex film noir, full of fine performances, murky atmosphere and a gripping climax. At the same time the picture seemed to up-end many of the standard detective genre conventions. They just didn’t understand it, and Arthur Penn, recalling Bonnie and Clyde, must have been thinking, Here we go again.

Sharp blamed Penn for what he perceived as the ambiguous structure, which, he said, ‘stemmed from Arthur’s uncertainty about the kind of film he was going to make’. During their disagreements over the script he expected Penn to put his foot down and stick to his own ideas, ‘which I felt was not only his right,’ said Sharp, but his duty as an auteur director.’

Director Arthur Penn Interview

The screenplay was originally called The Dark Tower. Was it you who came up with the title Night Moves?

Arthur Penn: Yes. It was suggested in the dialogue itself, with the reference to chess, which was in Sharp’s script.

It was originally a Sydney Pollack project.

Arthur Penn: Actually I only found out about this quite recently. Apparently Pollack was associated with Mark Rydell, but they had some disagreement. The company folded, and the script became the property of producer Bob Sherman, who sent it to me and produced the film.

Your last two films were very pessimistic. Night Moves could be described as a parable on the impossibility of knowing oneself and other people. Elsewhere it has been referred to as “a commentary on the post-Watergate era.” The same could be said of The Missouri Breaks.

Arthur Penn: It’s true about Night Moves. It’s the reason why the theme of the Kennedys is so central in the film. John wasn’t the kind of hero we turned him into, even if he did personify the hopes of all those who had ideals back then, to the extent that we projected those hopes onto him. With his death, and then Bobby’s, a part of our existence and aspirations came to an end. It’s in this way that Night Moves is pessimistic, although I don’t normally look at my work from an optimistic or pessimistic point of view. My intention with Night Moves was to make a seventies detective movie as opposed to traditional detective films that always present a problem followed, at the end, by the solution. Night Moves presents a problem whose solution doesn’t exist to the extent that the character searching for the answers carries within him the impossibility of finding them. Harry Moseby’s inability to understand his own problems, to discover his own identity, leads to his inability to recognize that the problem–the case he has been hired to solve-shouldn’t actually concern him. Or, to put it another way, that he shouldn’t approach it in a way that is likely to allow him to solve it or even to understand its nature. Being a rather conventional person, he insists on approaching it conventionally.

You said in an interview with Sight and Sound that you considered Harry to be a “normal” character as opposed to the majority of your heroes who are rebels, misfits, outsiders. But do you see a connection between him and the others?

Arthur Penn: What interested me about Harry was being able to show a man who, without being a true outsider, is nevertheless alienated from the society in which he lives. He’s unable to establish meaningful connections with the world and other people. The alienation of a rebel like Billy the Kid is different. Harry’s alienation is somewhere between that of an outlaw and that of a “regular” guy.

In the same interview it seems as if you despise Harry, although the film doesn’t give this impression at all. Besides, doesn’t Harry do what all your characters do, to the extent that he wants to break out of the darkness?

Arthur Penn: I don’t despise him but rather his job, the very concept of a detective. With a few notable exceptions, detective films bore me and detectives are rather despicable people. They grant themselves the right to violate other people’s secrets, which is very different from a quest for truth and knowledge, a theme evident in most of my films. In that interview I think I was just expressing a kind of revulsion for men like the Watergate conspirators, people who spend their time spying on each other. Harry seems to want to find out the truth about himself, but in reality tries to separate this self-awareness from the criminal case he is investigating. By doing this he demonstrates what I was trying to say about this kind of man who imagines he can compartmentalize his existence, to build a wall between his private and professional lives, which of course is impossible. Detectives are a particular breed of person. Real detectives have personality, something that most detective movies before Night Moves denied.

Even though the screenplay has an extremely complex structure, everything is expressed visually and most of your recognizable preoccupations are there. Yet you say you made few changes to Alan Sharp’s script?

Arthur Penn: I must have been misquoted. What I meant was that the general spirit of the script remained the same but that I made a great number of modifications and additions in collaboration with Sharp. The film is very different from his original script.

At the moment when Harry makes out the pilot’s face through the boat’s glass bottom, one thinks of the Biblical quotation from The Left Handed Gun: “Through a glass darkly.” This time it is a play on words: “Through a glass-bottom darkly.”

Arthur Penn: That was certainly intentional.

Editing is very important in all your films, especially so in Night Moves, where shots are extremely fragmented and dislocated.

Arthur Penn: Very early on I felt that the film needed abrupt, disjointed, almost convulsive editing, something that might suggest a nervous tic. I don’t know exactly why but I wanted to make a movie based on this kind of rhythm. I discussed it with Dede Allen and we agreed on this idea.

Did the original screenplay include Harry’s search for his missing father?

Arthur Penn: No, I suggested that.

There is a particularly moving scene where Harry and his wife are lying on their bed talking about the day when he was reunited with his father. Hackman does something truly incredible, I have seen nothing like it in any other film. Susan Clark asks him a question that embarrasses him and for a moment he puts his hands over his face to avoid his wife’s gaze. When he removes his hands his face expresses something indescribable, a look that suggests shame, embarrassment, and guilt. But there seems to be no real “acting” going on, and Hackman conveys this all in a single gaze. You even get the impression that he is blushing. Did you give him specific directions for this scene, or was it a moment of inspiration on his part?

Arthur Penn: I remember the scene very well. It was a difficult one, and we needed several takes because Susan had trouble with it. With an actor like Gene I don’t need to give precise directions. He is able to produce the kind of reaction I’m after quite spontaneously, something he can do differently take after take. It just comes naturally to him.

And the fight in the kitchen?

Arthur Penn: There was nothing particularly difficult about the scene except it was a moment of intense violence. It’s the moment when tension between the two characters is so high that they’re capable of the absolute worst. Hackman has an extraordinary power that can be excessive, and I had to restrain him. There’s sometimes something murderous about him.

My Night at Maud’s

An often quoted line from Night Moves occurs when Moseby declines an invitation from his wife to see the movie My Night at Maud’s: “I saw a Rohmer film once. It was kinda like watching paint dry.” The exchange from Night Moves was quoted in director Éric Rohmer’s New York Times obituary in 2010. Penn himself was an admirer of Rohmer’s films; Jim Emerson has written that, “Harry’s remark, as scripted by Alan Sharp, is a brittle homophobic jab at a gay friend of his wife’s.” Bruce Jackson has written an extended discussion of the role of My Night at Maud’s (1970) in Night Moves; viewers familiar with the earlier film may recognize that its protagonist and Moseby have related opportunities for infidelity, but respond differently.

Scriptwriter Alan Sharp Interview

Can you explain the genesis of your involvement in the film, Night Moves?

Alan Sharp: Well, essentially the two genres that I was interested in writing about when I went to America were the Detective and the Western genres. In a way, they satisfied some requirements of detachment from personal content and yet allowed me to write about themes that interested me. I wrote Night Moves, the last of the five original screenplays that were made, while I was there.

Then it’s really your baby?

Alan Sharp: It’s my script and always was my script. When it was finished at least when it was a draft, it was showable. It was bought by Warner Brothers and the question of finding a director arose. As I mentioned, I wanted to take a detective story and set up a private eye who is made out to be the classic picaresque detective in an unravelling situation. Then, at some judicious point, I wanted to break from the detective story and change it over into an opposite genre-a melodrama, if you like. The story was intended to centre on Moseby, the crisis in his life, his relationship with a woman, the Florida Keys and the disintegration of his marriage. The brutal aspect of the piece, the “who did what to whom” thing, was intended to just stream behind as a kind of correlation, but not be what the piece was all about.

Right from the outset this was a problem to Warner Brothers. They could see the dangers of getting people in to see a classic theme and then abandoning it in mid-stride. Their decision was really going to be based on whether they could get a hot-shot director. They tried Frankenheimer; I didn’t feel it was his kind of picture. I thought it was just wonderful when they suggested Arthur Penn. In fact, I really didn’t think the script was good enough to go to Penn, and I protested. Finally, however, they decided to send it. I went along to talk to Arthur, once he had read it.

Arthur hadn’t been working for a couple of years. I think he had been trying to make a film on Antarctica and also a film called Ruby Red. Little Big Man was his last film before those, so he’d been about a long time-maybe close to three years. He needed a job and the script was interesting enough for him to get involved in it. When he read it, he didn’t think it was right. We met and talked; I was pretty keyed up by his interest and went away after some discussion-general discussion leading to no specific scripts.

Could you tell me if what he saw in the script was what you wanted him to see in the script, or didn’t that matter?

Alan Sharp: Well, your question captures what is, in fact, the endless dialogue that goes on between the writers and the director. What does the director really want; what does he know about your material? You see, I’ve always considered that a writer’s job is like being a lieutenant in somebody’s army. The writer is there to do the bidding of the director, but he requires the respect of the director to do that. Also, the director has to know at least as much about the material as the writer–which puts the director at a slight disadvantage if the material belongs to somebody else in the first place. That’s how the director’s got to get it up, though he’s got to know as much as you do, or else.

After your dialogue with Arthur, did you find the finished article congenial to your script?

Alan Sharp: No, we pretty thoroughly failed at what we had set out to do with the material. There were problems and we worked a long time on the script. We had about six months of close collaboration which involved a lot of rewriting-I mean a lot. Some of the parts that we wrote many, many times were never resolved. When the script finally boiled down to become a little more coherent, it became apparent that Arthur didn’t really want to make a downer movie: that is, he didn’t want to make a movie in which everybody got the shit kicked out of them. I must say my instinct was mostly in that direction because my allegoric content with Moseby was America post-Watergate, post-Nixon. Actually, Watergate was happening right at the time. There was its whole disenchantment versus the Kennedy syndrome: where were you when Kennedy died, the running through of American heroes, that sort of thing….

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Could you elaborate?

Alan Sharp: Yes. One of the advantages of writing generic material, I find, is that I can be fairly self-conscious about the intellectual content because I can keep the two things apart. If I were writing a book, for instance, I would find it much harder to be as intellectual about the content. I would have a harder task disguising the bare bones of the themes.

The script was originally called “An End of Wishing,” which tells you a little more of what the script was about.

Alan Sharp: That name, however, did not stick and Night Moves was the one agreed upon, even though it wasn’t my title, Nevertheless, it was a time for a certain kind of consciousness, which I’m calling American: a recognition that the world is more complex than what it was believed to be and that there are things that just cannot be solved. Also, the understanding that Americans will not always be able to triumph in all things undertaken-Moseby was the personification of that idea.

Would you go so far as to describe that as an existential approach?

Alan Sharp: If you mean, was it intended in some way to filter all of the preoccupations of life through a narrower aperture, the genre aperture, then yes! I was preoccupied with “What’s it all about” and “what do you do when your life doesn’t make sense to you” and all that kind of thing. Yes, definitely. I mean it has origins in film noir. I am very partial to movies out of the past-they’re self-conscious enough in that sense and there are little buffy kinds of things in this film, like the “ghetto” and the Keys. Paula’s first boyfriend, the little town, Malone and Billy Danruther-that’s a Bogart name; they give you personal pleasure. There are a lot of little stitches in it, but it was essentially an allegory about what I perceive to be the American consciousness, both its strengths and its blind spots, and Moseby was the guy representing that.

I make a distinction between Westerns and Detective stories in that in Westerns, the heroes don’t really ask questions of themselves-they only ask questions of the circumstances in which they find themselves. In the detective story the heroes ask the question of themselves because they have perceived that the dilemmas they see outwardly are essentially internal dilemmas and they have to be solved from within. Well, Moseby was in that mold.

We had a lot of trouble dealing with this. The idea of taking the story so far and then just dropping the whole who done it” and “who stole it” and “who killed it” was too much. Nobody would really buy that. I initially wanted Moseby and Paula to take off on a trip, ostensibly with the boodle, so that there would be some basic narrative, I meant it to be a love relationship trip that would end in disaster as well. However, we couldn’t agree to that and I couldn’t convince myself that I knew definitely how to write it. So we started to work around the idea of resolving, within some parameters, the question of who stole what, while essentially getting on with their relationship: Arthur became less and less amenable to this approach. He didn’t want, for instance, the wife and the husband to separate in such a way that there was no hope for them, you know. To that extent we altered their farewell, their parting scene, to indicate that there was a chance for him to come back. Also, Arthur was extremely conscious of the fact that he wanted and needed to make a commercially successful film–this was slowly becoming more evident to me. The really crucial thing was that the film cost quite a lot of money for what it was.

How much?

Alan Sharp: It cost about four million dollars and that was a lot of money then. Actually, that expense was quite unnecessary. It didn’t have to be like that. I think Hartley got about half a million dollars, but the above-the-line cost of everybody, Arthur included, must have been about a million and a half. The film could have been made more cheaply, and although nobody thought about it at the time, that was what ultimately sank it at the box office. When Warners saw that it wasn’t going to do business, they just pulled their money out. The film might have made its money back at two million, but it wasn’t going to make its money back at four million, In the end, the money that was spent on the film rebounded against its chances of being commercially successful. That was never a problem for me; I never actually thought the film was a particularly viable prospect, commercially.

Did it end up commercially viable?

Alan Sharp: Well, it never made a cent then and it never will now. The studios have a system where they can almost perpetually defray expenses on a thing like that. Nobody that I know, and I know most of the principals, expects that they are going to get money back on Night Moves. When we finally got up to the wire to make the movie, it took me quite a while to actually accept the fact that Arthur didn’t know what he wanted to do. We still didn’t have a completed script when we began shooting and we had been given about a ten-day rehearsal, which is not all that frequent. It was then that I realised we weren’t working very well.

There were some problems with the movie when it was made which, I think, stemmed from Arthur’s uncertainty about the kind of film he was going to make. We exhausted quite a number of conversations during which I expected Arthur, at some time, to step in and say, “O.K. here’s my hero; this is my Moseby,” which I felt was not only his right, but his duty as an auteur director. That never really came out. But we had very amiable relations throughout. Arthur is not an easy guy to quarrel with; he’s a very civilized, intelligent and liberal kind of guy and I have no quarrels about him personally. Arthur shot the film and everybody was quite excited by the interesting things happening. Hackman was just wonderful-we knew he was going to be good.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Were you happy with his casting?

Alan Sharp: I think it was fantastic. It’s hard for me to imagine who’d be better than Gene Hackman, although he was, in the end, one of the liabilities in the film. You see, people don’t go to see Gene Hackman movies, although sometimes they go to see movies that Gene Hackman is in. His gift is that he’s not a star; he was excellent and the supporting cast was really pretty good. At the time, I think people thought Jennifer Warren was really powerful. There was a scene in the film which was, I suppose, the film’s emotional thematic centre: Moseby and Paula make love when she has managed to keep him out of the way of some other kind of skulduggery. The sequence consisted of a big two page soliloquy by Paula while she was being made love to, which was a long kind of litany about her youth, the death of Kennedy and the disintegration of the dream. We shot that and we were all very impressed with her performance because it was a hard gig, you see. She had to be choreographed to include her orgasm-a risque scene. It was kind of Shakespearean and it came off pretty well. I felt that this scene, no matter what else didn’t work in the picture, said, “Well, this is what we’re about. We’re about something that is pretentious,” that is, about having a point of view on a very complex issue and yet trying to incorporate it into the genre of entertainment, if you like. We were always very pleased, Arthur finished the film, I think, on time, but he shot an enormous amount of film, which was rather distressing. He shoots a great deal of footage and cuts it, so that you don’t shoot the scenes as scenes-you just shoot them for cover. Consequently, you don’t have any sense of footage shot whilst you’re working. I was on the set about fifty to sixty percent of the time, in a good position. I was a close friend of the producer. I got on well with Arthur and I was able to talk about what we were doing. I didn’t have producer status, of course, but I was there.

Could you tell me about Paula’s litany as you wrote it and as it was filmed originally? Where would that have place in her life, in terms of the film?

Alan Sharp: Paula was a generic American female. She is one of those slightly shop-soiled, self-respecting women who don’t really expect it’s ever going to get all right. I have always admired American women as “typed,” admired their directness, their willingness to try things and their naivety. Paula was supposed to be that heroine.

What did she mean when she said, “You ask the wrong questions?” Why wasn’t she more giving?

Alan Sharp: Paula, you see, was a few steps ahead of Moseby and she had already come to the conclusion that he was only just beginning to realize there were no conclusions. It was part of my intent that all the other characters in the film were, in their own way, honorable; they attended to life in their own lights and from a central point of view. There were things to be said about all of them. It was time not to have that point of view anymore, to stop judging people, Paula represents that. She just says, “What the fuck?” She says about her guy, “He is one of the few guys that gets nicer when he’s drunk, and if you live here, that’s a very valuable and important thing to have in a partner. He might not be much else otherwise.” She was, then, a more enlightened head.

In the post-Vietnam and post-Watergate era?

Alan Sharp: Yes! She had already absorbed much, but I must say the Watergate was not really making all that much impression on me. I knew of it, but we were shooting the film, and it was only just dawning on me.

Was it more post-Vietnam then, this turning point?

Alan Sharp: I’m not a particularly astute observer of contemporary history. It had more to do with a poetic idea for which I could never produce documentation. There are plenty of harbingers of Moseby in other detective fiction I didn’t come up with Moseby. I mean Chandler’s Marlowe contains as much self examination and angst if you like, so that I’ve no claims of originality in this. No, it was rather I had a poetic idea of the doomed hero.

He is doomed, then? Is the final shot, the visual, that of a man who’s literally and figuratively all at sea?

Alan Sharp: Yes. We had a long discussion about this. Arthur, the producer, and Warners were all very keen that the last shot where you saw Moseby didn’t say he was dead. I believed that he should be dead, particularly since we had set up a scene previously, in which if he had escaped, he could have gone back to his wife. At the airport his wife was supposed to say to him, “You go down your tunnel.” He said, “I’ve got tunnel vision. I get this out of focus.” She said, “You go down your tunnel and I’ll go down my tunnel. When we get to the other end, we’ll look around. If we can see each other, maybe we’ll do something. If we can’t, we’ll go on our way.”

Well, we didn’t play that scene. Instead, we played a scene in which she said, “If you don’t go, you can’t come back; and I’ll be here.” She sounds like a good little missus, and that wasn’t for me. Given that, I didn’t then want the ending to be Moseby with a make-up wound in his legs, steering the boat back home. We got an ending which, I guess, aimed dead at the centre of ambiguity. Maybe it stuck, I don’t know. When Paula said to him, “Well, you solved the case,” Harry said, “I didn’t solve the case; it just all fell in on top of me.” That was intended to be where Moseby was at. His life was strewn all over the ocean, and as an image I’ll buy the circling boat. It was intended, certainly by me and less so, I think by Arthur, that there should be a pessimistic conclusion to the piece.

Forgive me if I am straying into a sensitive area here, but your age and Moseby’s age are approximately the same. Is there any further source there?

Alan Sharp: Yeah, well, you see, I had been preoccupied with what I was going to do when my wife had an affair which she did, about eighteen months later, I have a lot of fuel for those particular scenes-personal fuel. Also, I know now that Hackman actually constructed many of the character’s mannerisms on his observation of me, because that came up later. A lot of people would say, “Hackman-what kind of fella is he?” It never crossed my mind, quite frankly, what he was doing.

So he had been studying you?

Alan Sharp: Apparently.

It sounds very professional of him, to that extent.

Alan Sharp: Oh, yes! He’s an exceptionally professional and skillful actor, He’ll do anything up to six takes and just go on adjusting each take. He won’t change it so you get a different reading or interpretation, but he’ll give you four or five variations just to give you choices. He’s a wonderfully skilled actor who seems able to make very complex perceptions without having to verbalize or intellectualize them. He was marvelous for that. Lines that had been written just to get you from one line to the next line came alive with him. In his scene with Deli, when she cries out and he goes over and sits with her, he says, “It’s bad when you’re sixteen but when you’re forty, it’s no better.” This was stuff that was much better than what was written on the page. When I saw that rendition I was astonished; there was that personal content which I found worked successfully.

Did you write the chess pun, “(K)night Moves?

Alan Sharp: Well, the game he mentions is a game that I’ve known about for quite a long time and which I’ve written about in one of my novels, as well. It’s another classic instance of the detective unfounded. One of the players in the game, which was played in 1926, achieved a particularly elegant mate: the queen sacrifice and the three little Knight moves. They just go curling in at the back and he didn’t see it; he missed it, as the guy said. To some extent, I knew that there was little chance of everybody perceiving the nature of this move on a screen while the rest of the action was going on. Nevertheless, it was a precise metaphor for Harry’s condition, so I didn’t see why I shouldn’t use a diamond. Even if if were covered by a cloth; it had the right to be there. To that extent, the chess metaphor represents Moseby as an introspective, internalized man of action.

Do you see that as a contradiction in any way?

Alan Sharp: No. I see it as the great classic tension-to be grandiose for a moment. It’s MacBeth. It’s the guy who, in the end, is only free when acting, but whose life is mostly strangled by thought. Moseby was that, but at a much lower point on the scale. His dilemma was this: while he released himself in action, he moved from a world in which that action was coherent to a world in which it was less coherent. He was unable, really, to resolve any of his internal dilemmas by solving the case.

Does that work against the Detective genre?

SHARP: Yes. It’s the detective who can’t solve the case and for whom life has become so complex that there are no solutions. That is because the answers you’re going to get don’t relate to what you’re asking about.

In the last sequence, when the statue is brought to the surface on the rubber raft, we see a stone figure that is almost bisexual in appearance. It has a womb-like, concave stomach and a stubby penis. This seems a Freudian expressiveness, relating back perhaps to Moseby’s parent problem?

Alan Sharp: I had no part in that. Initially the boodle was going to be drugs, but Arthur didn’t want to make a film about drugs and I agreed. To me the boodle was unimportant; it was just what made the story turn over. Arthur wanted it to be something less malevolent and so they came up with the artifact idea, which we then incorporated all the way through. The actual creation of the artifact was not mine. I hadn’t even seen the object until I saw it in the movies.

Having seen it, were you disapproving or delighted or what? It is, after all, a distinctly sexual figure.

Alan Sharp: Yes, I remember what it was like. It looked like some sort of large, sacrificial trough or container of some kind; the concavity was in the body of the piece. Since I had not been the originator of the image, I really did not attempt to work it out. It was Arthur’s idea and I had almost no views about it. I simply know the demarcation between something that is of my origin and of Arthur’s. Quite frankly, I thought it more likely to have been the creation of the Art Director because I remember Arthur giving the Art Director the task of coming up with a sufficiently bizarre object which would also perform the function of breaking the seaplane. It was an internal, logistical problem. I won’t minimize Arthur’s mental input or projection onto that, but it had no context for me.

The images struck me forcefully. Throughout the film, we were presented with the idea that what you see doesn’t always tell you something. The number of times Harry looks and fails to interpret what he’s seeing seems important. For example, as Moseby drives away after returning Deli to her mother, he winds up the window so that we do not hear, but merely see. The nature of the quarrel he’s watching is, therefore, unclear. The visual information doesn’t yield anything and I think that’s a dominant motif in the film.

Alan Sharp: I would have to give that to Arthur. It is clearly a corollary to the idea of the detective who cannot make sense of his input.

So Arthur put in images that actually suited your intentions?

Alan Sharp: Oh, yes. If I have given the idea that Arthur Penn got into this merely because he had to do a job and this was the nearest thing to go, I didn’t mean it. Arthur was exceedingly interested and had a lot of input. He is a very shrewd person to work with. I watched Arthur and Allen, his editor, work in the cutting room. They were applying a very rich surface texture to the material-this was the justification for the hundreds of thousands of feet that Arthur shot, but it meant that when he and Allen got back there, they had a lot to work with. He did create a visual corollary to the content. There is almost nothing in the piece that I would say was visually dictated by the script.

Were there things that weren’t in the final version that you would like to have seen go in?

Alan Sharp: Arthur finally edited a film which, if I remember correctly,was about one hundred and seven minutes long. I saw it in New York. It was a fine act and I must say I was very well pleased. However, from my point of view, I thought the piece didn’t work. I felt that I hadn’t done my job completely; I knew areas which had fallen apart. Arthur had had trouble with Hackman towards the end of the film when his uncertainty about so many things began to accumulate. On the other hand, I knew I was looking at a piece that was interesting, complex and well worth thinking about. Arthur then took the film to Hollywood after cutting it in New York and screened it for some friends of his-Rafelson, Nicholson, Warren Beatty and Terry Malick. I wasn’t at that screening but I know that, at the end of it, there was conveyed to Arthur the idea that Moseby was not a particularly sympathetic character, as heroes should be. I felt this was as it should be; Moseby transcended sympathy. It wasn’t necessary to be personally sympathetic to his plight if you were concerned about his allegory. This is hearsay, but Arthur, as a result, cut about eight minutes out of the film to tighten it up, to pace it. He removed Paula’s long soliloquy because it made Paula so strong a character that Moseby’s reaction to her afterwards only enhanced the idea that he didn’t know what the fuck he was doing-which was exactly right. Arthur was trying to speed the film up and to sharpen Moseby’s character, which caused a lot of trouble between Arthur and me, I just couldn’t buy that as an argument. It just seemed that cutting out Paula’s scene wasn’t going to change the nature of the film. This scene was, really, the fulcrum of the action.

Arthur’s argument was that Moseby wasn’t going to come back and get Paula, so to make Paula a lot more interesting and dangerous, and to kill her off, was a good solution to the problem. I think he “lessened” the piece so that its flaws were not so naked. That hurt me a lot. It was the first time I had ever been creatively offended working in Hollywood. I’ve always been as careful as I could not to take it too personally and not to believe in the absolute integrity of this work; but we had shot that enthusiastically, even though the material was a bit risque.

You have people of various ages in Night Moves. What can you tell us about Deli? Is she derivative?

Alan Sharp: I’ve never really had very many affairs with girls of Deli’s age. That might be ahead of me. My oldest daughter is about twenty three now and when I was writing Night Moves, she was about Deli’s age. The only thing that I put into Deli, from my experience, was that people much younger than you only seemingly share the same language. You have a verbal commonality but no content commonality. You don’t know anything the younger person means and Deli was the living proof that, in a way, there is no communication to be had. The life of people in their fourteen’s and fifteen’s is a kind of wonderment to me. I don’t learn from my own life at that age because I don’t remember it. I remember, though, being a person who thought a lot because I’ve always been stuck in here, inside me. Deli represented those beings who can live on the surface of the world and seem to be as one with the natural environment. I know very little about painting but there is a David Hockney thing about her. Deli was somebody whose fusion with life was both enchanting and totally inaccessible. She represents. I suppose. the kind of amoral innocence which you can have no con are way beyond being able to engage in it. In the film, she’s there to prod Moseby with a sense of how encased he is in his thoughts about things. When he comes to get her and she talks to him on that jetty, he has the sense of, “What’s the big deal?” It’s the cracking of the carapace that’s around him.

I wrote a novelization of Night Moves which extended my script. You would find it interesting. I’m usually a turgid, purple-prose writer, but in this book I gave away all that shit and wrote it, not so much as notes upon a screenplay, but as a little novel. Also, there’s a lot of speculation and background filling-in of many of the things you have asked me about.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

POST PRODUCTION/RELEASE/DISTRIBUTION

When Paula (Jennifer Warren) comes to Harry’s room late in the evening, eventually they make love. As initially shot, that sex scene was longer, and vividly intense. (In my interview with Warren, she described the scene as “intimate emotionally as well as physically.”) But to enormous (within the production) controversy, Penn decided to delete the more elaborate (and by seventies standards, risqué) encounter and go instead with the truncated version. Screenwriter Alan Sharp fought for the longer scene’s inclusion, describing his “huge disagreement with Penn” over the issue and how he was “offended” by the decision. More intriguing still is that Penn’s most intimate collaborator – on this film and many others – editor Dede Allen, described it as “a wonderful scene, just heartbreaking.” She was also, in her words, “very, very upset,” when Penn chose to cut the scene.

Shot in 1973 on the tail of a writer’s strike and unreleased by Warner Bros. until 1975, Night Moves had the misfortune to follow Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1973), Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye (1973), and Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974) into cinemas; it emerged during a glut of so-called “neo-noirs” (among these, Dick Richards’ Farewell, My Lovely, Stuart Rosenberg’s The Drowning Pool, Robert Benton’s The Late Show, Michael Winner’s The Big Sleep, and Walter Hill’s The Driver) films that recalled the postwar noir thrillers but with a contemporary edge. Lost in the shuffle of Byzantine plot mechanics, sundry deceptions, twists, and double crosses was Penn’s ruminations on identity and the guttering of American self-respect. The filmmaker infused elements of his own life into the Night Moves script and his feelings of failure within the Hollywood community. Audiences and the majority of the major critics were apathetic to the plight of a private investigator who is unable to solve his big case because he is handicapped by his inability to see his own life with honesty.

Warners decided to shelve it for a while. Nine days after Night Moves opened across the nation, Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) premiered at the head of a $2 million publicity blitz. Penn made one more feature – the similarly maligned revisionist western The Missouri Breaks (1976) – before retreating for a time to theatre.

Seldom revisited but never forgotten, Night Moves has enjoyed a slow appreciation of its critical market share over the course of forty years. Key to the film’s happy reappraisal is its atypicality and freshness, a quality gained by willful forfeiture on the part of Penn and cinematographer Bruce Surtees of the standard noir curlicues – the high contrast shadows, the smoke-filled rooms, the canted angles – which would have rendered the film at best rote or at worst kitsch. Hackman’s gumshoe Harry Moseby has lost nothing in topicality over the course of four decades but it is the minor players who sell the story, none more so than Jennifer Warren as the quirkiest, most conflicted, and yet most oddly appealing femme fatale in the crime film canon. (A long-standing rumor maintains that Faye Dunaway turned down Night Moves to costar opposite Jack Nicholson in Chinatown; in fact, Dunaway’s manager, Sue Mengers, used a nonexistent offer from Penn as a bargaining chip to win her client the role in the Polanski film over short list rival Jane Fonda.) Night Moves also provided early work for rising stars James Woods and Melanie Griffith. Six months after the film came and went at the box office, singer-songwriter Bob Seeger had a Billboard Hot 100 hit and near overnight success with his – allegedly unrelated – single “Night Moves.”

youtube

CAST/CREW

Directed

Arthur Penn

Produced

Robert M. Sherman