#Seymouria sanjuanensis

Text

Happy Valentines Day

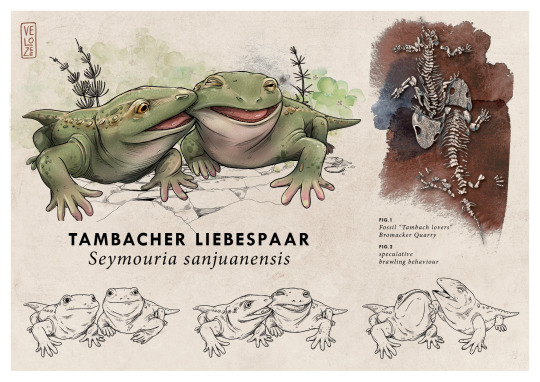

Here is my favorite couple from Thuringia, the Tambacher Liebespaar (tambach lovers). A fossil of two skeletons of Seymouria sanjuanensis from the Bromacker quarry

#digital illustration#velozee#paleoart#paleontology#permian#fossil#illustration#Seymouria#Seymouria sanjuanensis#Tambacher Liebespaar#Bromacker#Valentines Day

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The "Tambach lovers", a pair of Seymouria sanjuanensis from the Tambach Formation of Germany. This is a cast of the original fossil displayed at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA

By James St. John

0 notes

Text

The Bromacker Project Part VI: Seymouria sanjuanensis, the Tambach Lovers

Two exquisitely preserved, nearly complete adult skeletons of Seymouria sanjuanensis that were discovered in the Bromacker quarry in 1997. Photo by Dave Berman.

At lunchtime on the last day of the 1997 field season, Thomas Martens discovered the two exquiste specimens shown above, the only fossils found that year. Thomas had uncovered a piece of the hip region with some attached vertebrae that resembled, once again, those of the ancient amphibian Seymouria. Because our work time was limited, we estimated the length of the specimen and rushed to extract it from the quarry. When we flipped the block over, a few pieces of rock fell out, revealing a series of vertebrae of a second individual in the block. We were thrilled to learn that Thomas had discovered two specimens of Seymouria. We put the rock pieces back in place and quickly finished plastering the block. There was just enough time for Dave, Stuart Sumida, and I to return to our hotel, clean up, quickly pack, and meet Thomas, his family, and his fossil preparator Georg Sommer for a celebratory dinner. What a great way to end the field season.

Working in tight quarters to quickly extract the Seymouria specimens discovered at lunchtime on the last day of the field season. Clockwise from right: Georg Sommer, Dave Berman, and the author. Photo by Stuart Sumida, 1997.

Seymouria had already been known from the Bromacker quarry. Thomas had discovered and identified two skulls in 1985, fossils he brought with him when he came to Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) in 1993 to study for six months with Dave Berman under a CMNH-financed fellowship. Both skulls were of juvenile individuals. Of the two known species of Seymouria, Dave and Thomas were excited to discover that the Bromacker skulls were nearly identical to those of Seymouria sanjuanensis. The 1997 lunchtime discovery of the two complete adult specimens confirmed the identification of the Bromacker Seymouria as S. sanjuanensis.

The first discovered species of Seymouria was Seymouria baylorensis, from near Seymour, Baylor County, Texas, from which its name was derived. Seymouria sanjuanensis was first found in San Juan County, Utah, by Dave Berman and the field team he was leading as a graduate student at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dave’s advisor, Dr. Peter Vaughn, named it Seymouria sanjuanensis in reference to the county of discovery. Another discovery of five specimens of this species preserved together was made by Dave in New Mexico in 1982.

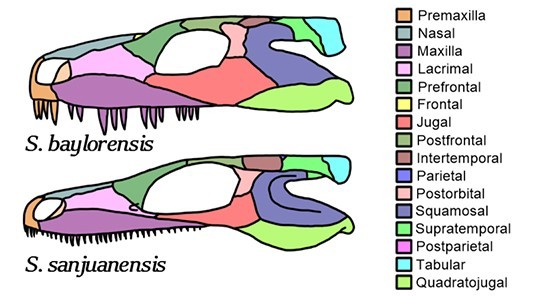

Comparison of the skulls of Seymouria baylorensis (top) and S. sanjuanensis (bottom). The individual bones of the skull are color coded. Skulls scaled to same size. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Seymouria baylorensis is geologically younger than S. sanjuanensis and has a more robust skull, larger and fewer teeth of variable size, and a subrectangular postorbital bone compared to the chevron-shaped postorbital of S. sanjuanensis.

Seymouria is considered a terrestrial amphibian that only returned to water to breed. Its strongly built skeleton provided the support needed to move on land. With its numerous, slender, pointed teeth, S. sanjuanensis most likely ate insects and small land-living vertebrates. We know that the Bromacker Seymouria didn’t consume fish, because not a single fish fossil, scrap of fish fossil, or fish coprolite (fossil poop) has ever been found at the Bromacker quarry. Study of the rock deposits preserving the fossils at the Bromacker indicate a lack of permanent water, which would explain the absence of fish.

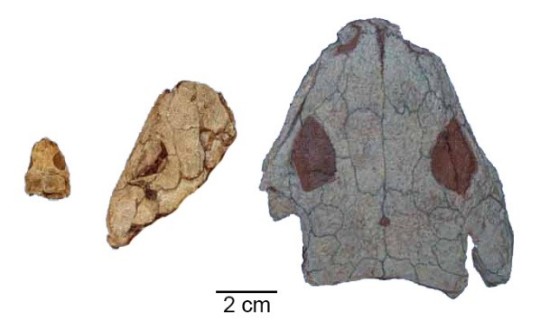

Growth series of skulls of Seymouria sanjuanensis from the Bromacker Quarry showing (left to right) early juvenile, late juvenile, and adult growth stages. Photos by the author, 2006.

Conditions for breeding must have been favorable in the Tambach Basin, the ancient basin where sediments preserving the Bromacker fossils accumulated, because several juvenile specimens of Seymouria are known. The smallest is a skull measuring about 3/4 of an inch long. In a study led by our colleague Josef Klembara (Comenius University, Slovak Republic), we determined that the smallest individual was post-metamorphic—in other words, no longer a tadpole—based on the presence of certain ossified bones in the skull. In tadpoles, these skull elements are cartilaginous; that is, they haven’t yet turned to bone.

Five skeletons of Seymouria sanjuanensis preserved together were discovered in north central New Mexico by Dave Berman in 1982. These specimens are on display in CMNH’s Benedum Hall of Geology, in the “What is a Fossil?” case. Photo by the author, 2013.

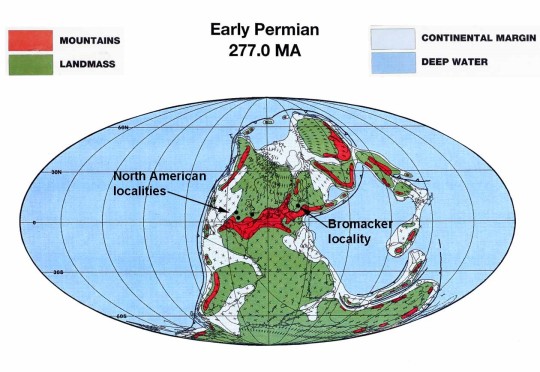

The discovery in Germany of the same species of Seymouria previously known only from New Mexico and Utah has important implications in terms of paleobiogeography (the study of the distribution of species in space and time). At the time S. sanjuanensis was alive, the continents were merged to form the supercontinent Pangaea. The presence of S. sanjuanensis across Pangaea, north of a roughly east-west trending mountain range, indicates that climatic or physical barriers (e.g., deserts, inland seas, mountain ranges) didn’t prevent its dispersal.

Map showing the arrangements of the continents in the Early Permian. The locality where Seymouria occurs in present-day New Mexico, Texas, and Utah and the Bromacker locality in present-day Germany are indicated. Map modified from Scotese, 1987.

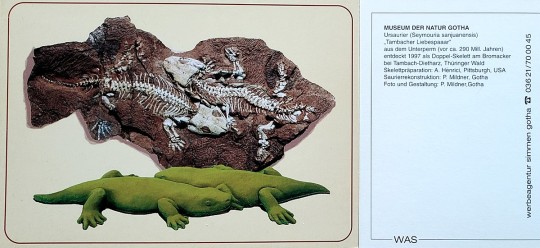

The two Seymouria specimens preserved together were a big hit in the local region in Germany. Museum der Natur (MNG) exhibit preparator Peter Mildner nicknamed them the “Tambacher Liebespaar” (“Tambach Lovers”) after a painting entitled “Gothaer Liebespaar” (“Gotha Lovers”) on exhibit in the Herzogliches Museum of the Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein (also the parent organization of MNG). This name caught on and is fondly used by our German friends and colleagues. Peter even made a fleshed-out model of the two Seymouria specimens in their death pose. The proprietor of the hotel in which we stayed hung a copy of the model of the Tambach Lovers and a framed collage of newspaper articles featuring the Bromacker on a wall in one of the hotel rooms, which she named the “Präparation Suite” (i.e. “Preparation Suite” in reference to the preparation of fossils). I often stayed in this room.

The painting entitled “Gothaer Liebespaar” (“Gotha Lovers”), which is on display at Herzogliches Museum of the Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha, Germany. Image from Wikimedia Commons and provided by Thomas Martens.

Postcard showing the Tambach Lovers. The postcard was made for and sold by the Museum der Natur, Gotha. Photo of the postcard by the author, 2020.

Stuart Sumida (left) and Heike Scheffel, proprietor of the Hotel Wanderslaben where we stayed (right), with the model of the Tambach Lovers in the “Präparation Suite.” The framed collage to the right of the model holds newspaper articles featuring the Bromacker project. Photo by the author, 2003.

A cast of the Tambach Lovers specimen and a model of Seymouria sanjuanensis are exhibited in the Fossil Frontiers display case in CMNH’s Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition. Be sure to look for them once the museum re-opens. And stay tuned for my next post, which will feature the unusual bipedal reptile Eudibamus cursoris.

For those of you who would like to learn more about Seymouria sanjuanensis, here is a link to the publication describing the 1997 specimens: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020%5B0253%3AROSSSF%5D2.0.CO%3B2.

Amy Henrici is Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Bromacker Quarry#Seymouria sanjuanensis#Fossils#Paleontology#Vertebrate Paleontology

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buon nuovo 2018

Quando nel millennio scorso gli uomini pensavano al 2018, immaginavano essi stessi come degli alieni senza il problema delle macchine parcheggiate in doppia fila. Avrebbero colonizzato i cieli e spazzato via le galassie, si sarebbero fatti il bagno nella Via Lattea come Poppea e posizionato veicoli astrolabici sulle Twin Towers, che in capa a loro sarebbero state abbattute forse solo a causa di una guerra a fuoco incrociato con i marziani e i venusiani. Ci si figuravano bisnipoti con la capa a uovo e gli occhi rotondi ma anche a mandorla, ché i pesielli di Mendel e le sue teorie sarebbero stati buoni nemmeno per conzare il brodo, perché nel 2018 si sarebbe sicuramente preparato il brodo anche con i pesielli. Mai si sarebbe pensato a feste di fine anno con la loro musica ancora a suonare: i dischi incastonati nelle piastrelle delle piscine in vetrocemento sarebbero stati reperiti all'intrasatta e fatti studiare ai criaturi sui sussidiari virtuali a dissolvenza negli occhialini del futuro e nelle lavagne digitali al plasma. Le maestre avrebbero interrogato gli studenti: "Questo fossile cos'è?" - "È uno scheletro di Seymouria sanjuanensis" - "No, ciuccio, è 'Total Eclipse of a Heart' di Bonnie Tyler" e avrebbe così seguito per punizione la traduzione di tutti i brani. Negli anni passati si sono fatti male i conti: nonostante l'effetto serra e i passi da gigante della tecnologia, sono cambiate poche cose e non è dato sapere se per fortuna o purtroppo. Quando il passaggio alla Nuova Era avrà una datazione precisa e segnerà l'anno Mille simbolico nel cuore dell'umanità eletta, suoneranno gli smartphone con la comunicazione criptata che segue, un invito da parte dei messi degli equilibri cosmici a un cambiamento profondo dello spirito:

Complimenti! Sei stato selezionato per provare a vincere un robot da cucina del valore di 1.259€! Compila il sondaggio, clicca qui: http://zn.auguri/afessemammeta

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bromacker Contest Submission #1

DANCE IN THE DUST

Thuringian Forest Basin - Early Permian

Featuring a brawling version of the 'tambacher liebespaar', the famous fossil of two Seymouria sanjuanensis, that appear to dance through a drough striken walchia grove. Beneath their feed, small Thuringothyris mahlendorffae, basal reptiles that are believed to fill the niche of small rodents, perch from their borrows.

Despite of the rough climate the grove is still full of life. Inhabitet by insects like Anthracoblattina and Myriapoda. Adapted to the bromacker climate, their daily struggle for nurishment and reproduction gives the scene a nuance squirming live.

The dust that has risen from the dancing reptiliomorphs serves as a veil for the eco systems apex predator Dimetrodon teutonis.

None of my work got a prize in this contest but I still adore this picture very much.

Like what you see? Leave a tip :)

#illustration#digitalillustration#velozee#Paleoart#Bromackercontest#Bromacker#Walchiapiniformis#Myriapoda#Anthracoblattina#Thuringothyris#Dimetrodonteutonis#Dimetrodon#Seymouriasanjuanensis#Seymouria#Synapsid

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bromacker Project Part V: Orobates pabsti, Pabst’s Mountain Walker

In 1995, my first year of field work at the Bromacker quarry, Stuart Sumida discovered a fossil that we initially thought was that of the amphibian Seymouria, based on the size and shape of the exposed vertebrae. This tentative identification made sense, because before our collaboration began, Thomas Martens had discovered in the Bromacker a skull of Seymouria, a creature known from localities in the USA. Months later, while I was preparing the specimen, Dave Berman and I realized the fossil wasn’t Seymouria, and that it belonged to the same unnamed animal that Thomas had collected a partial skeleton of before our collaboration began.

Specimen of Orobates pabsti collected in the 1995 field season. We determined that it is a juvenile. Photo by Dave Berman.

In the 1998 field season I discovered a third specimen, which is by far the most spectacular fossil that I have ever discovered. I found it towards the end of the field season when I pried up a piece of rock from the quarry floor. Upon turning over the rock piece, I saw an articulated foot preserved in it. I couldn’t believe my eyes! I knew that at the Bromacker if an articulated foot was found, the rest of the articulated skeleton should be attached to it. The problem was, we didn’t know if I had discovered a front or a hind foot, so we weren’t sure how the specimen was oriented in the quarry and whether it penetrated the nearby rock wall. Dave carefully lifted another piece of rock and thought the bones exposed in it were part of the shoulder girdle. Unfortunately, closer examination revealed that it was a piece of skull roof—another lobotomy—but, lacking x-ray vision, this is how we find fossil bone at the Bromacker. The good news was that the fossil specimen appeared to parallel the quarry wall.

A film crew from the regional MDR television station visited us early on the day of my discovery to interview Dave and Thomas. The discovery was made after they left, so Thomas immediately notified them. They returned and recorded a reenactment of my discovery. The piece of rock I am holding contains the foot. The rest of the fossil lies in the low mound of rocks in front of me. Photo by Dave Berman, 1998.

Dave and Stuart finish plastering the block. The red flag is a north arrow to indicate the orientation of the block in the quarry. Photo by the author, 1998.

Dave, Stuart, Thomas, then-graduate student Richard Kissel (University of Toronto, Mississauga), and I named the animal Orobates pabsti, which is from the Greek “oros,” meaning mountain, and “bates,” meaning walker, in reference to the Bromacker fossil environment being an intermontane basin. “Pabsti” is in honor of Professor Wilhelm Pabst for his pioneering work on the Bromacker fossil trackways.

We determined that Orobates is very closely related to Diadectes, and like Diadectes, was herbivorous. Orobates differs from Diadectes and other diadectomorphs in the group Diadectidae in a number of features, some of which are as follows: spade-shaped cheek teeth that are oriented on the jaw at an angle of 30–40° to the jaw line, rather than being close to 90°; narrower and shorter vertebral spines; 26 vertebrae between the head and hip (Diadectes has 21); proportions and shapes of individual toe bones; and digit (finger or toe) length.

Holotype specimen of Orobates pabsti, the specimen collected in 1998. If a series of specimens exists of a new species, then the specimen that best represents the species is designated as the holotype. If only one specimen is known, it becomes the holotype by default. Photo by Dave Berman.

The Bromacker has long been famous for its exquisitely preserved fossil trackways. Identification of the particular fossil animal that made a given trackway is almost always very difficult, because body fossils often lack completely preserved hands and feet and typically are not found in association with trackways. As a result, trackways are given their own set of names, called ichnotaxa (“ichno” means track or footprint), which are typically referred to major groups of animals instead of individual species. The Bromacker is unique, however, because nearly completely preserved body fossils occur in a rock unit above the trackways, indicating they are very nearly contemporaneous. Five ichnotaxa are known from the Bromacker, and one of them, Ichniotherium, has been attributed to Diadectidae.

A large slab of rock being inspected for trackways shortly after it was unearthed in the commercial rock quarry. The polygonal patterns in the rock are mudcracks. Photo by the author.

Graduate student and trackway expert Sebastian Voigt (now Director at Urweltmuseum GEOSKOP, Burg Lichtenberg, Germany) often visited us at the Bromacker. In 2000, a time when Diadectes was the only known Bromacker diadectid, Sebastian and his advisor Hartmut Haubold (now emeritus at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, Germany) proposed that Ichniotherium cottae made two track types, designated as A and B, that differed according to the speed at which the trackmakers moved. This contrasted previous studies that proposed three species of Ichniotherium at the Bromacker.

Once the skeletal anatomy of Orobates became known, Sebastian realized that there were two species of Ichniotherium, and they were made by Diadectes and Orobates, respectively. He invited Dave and me to co-author a paper to present this hypothesis. We supplied Sebastian with information about skeletal differences between Diadectes and Orobates, and Sebastian used these data to firmly establish that Diadectes made Ichniotherium cottae (type B) tracks and Orobates was the trackmaker of trackways formerly identified as I.sphaerodactylum (aka I. cottae type A). Even though the makers of the trackways are now known, the ichnotaxon names are still used when referring to the trackways.

Photographs of trackways of Ichniotherium sphaerodactylum made by Orobates pabsti (top) and Ichniotherium cottae made by Diadectes absitus (bottom). Modified from Voigt (2007).

In Diadectes, the fifth digit of the hind foot is relatively shorter than it is in Orobates, which can be seen in the tracks of I. cottae and I. sphaerodactylum, respectively. Furthermore, in I. cottae trackways, the hind foot track overlaps the track of the front foot, whereas in I. sphaerodactylum the hind foot track typically doesn’t overlap the front foot track. This is because Diadectes has less vertebrae between the head and hip (21 vertebrae) than Orobates (26 vertebrae) does.

Front and hind foot track pair of Ichniotherium sphaerodactylum. Track made by the front foot is above the hind foot track. Digits 1–5 indicated. Modified from Voigt, 2007.

Front and hind foot track pair of Ichniotherium cottae. Track made by the front foot is above the hind foot track. Digits 1–5 indicated. Notice that the hind foot track overlaps the front foot track. Drawings are of different specimens than the one photographed. Modified from Voigt, 2007.

A cast of the holotype skeleton of Orobates pabsti is exhibited in the Fossil Frontiers display case in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition. Be sure to look for it once the museum re-opens. And stay tuned for my next post, which will feature the amphibian Seymouria sanjuanensis.

For those of you who would like to learn more about Orobates, you can access the abstract here or contact Amy Henrici here. The publication on the track-trackmaker association can be found here.

Amy Henrici is Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Bromacker Quarry#Orobates#Paleontology#Vertebrate Paleontology#Orobates pabsti#Fossils

17 notes

·

View notes