#Today we contemplate in him how sweet is the ‘yoke’ of Christ and indeed how light the burdens are whenever someone carries these with faith

Text

On the 23th of September is the feast day of St. Pio of Pietrelcina, priest

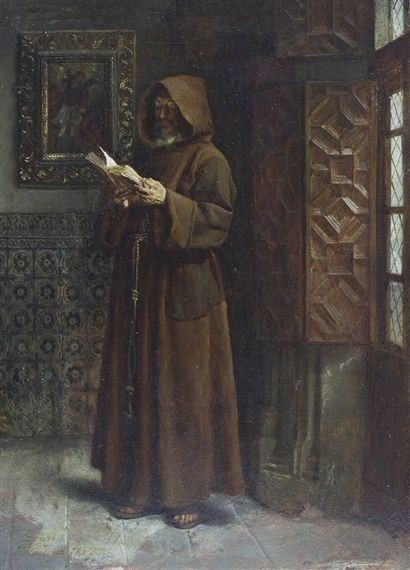

Ignacio de Leon y Escosura: Franciscan Monk Reading

Life of St. Pio of Pietrelcina

In one of the largest such ceremonies in history, Pope John Paul II canonized Padre Pio of Pietrelcina on June 16, 2002. It was the 45th canonization ceremony in Pope John Paul’s pontificate. More than 300,000 people braved blistering heat as they filled St. Peter’s Square and nearby streets. They heard the Holy Father praise the new saint for his prayer and charity. “This is the most concrete synthesis of Padre Pio’s teaching,” said the pope. He also stressed Padre Pio’s witness to the power of suffering. If accepted with love, the Holy Father stressed, such suffering can lead to “a privileged path of sanctity.”

Many people have turned to the Italian Capuchin Franciscan to intercede with God on their behalf; among them was the future Pope John Paul II. In 1962, when he was still an archbishop in Poland, he wrote to Padre Pio and asked him to pray for a Polish woman with throat cancer. Within two weeks, she had been cured of her life-threatening disease.

Born Francesco Forgione, Padre Pio grew up in a family of farmers in southern Italy. Twice his father worked in Jamaica, New York, to provide the family income.

At the age of 15, Francesco joined the Capuchins and took the name of Pio. He was ordained in 1910 and was drafted during World War I. After he was discovered to have tuberculosis, he was discharged. In 1917, he was assigned to the friary in San Giovanni Rotondo, 75 miles from the city of Bari on the Adriatic.

On September 20, 1918, as he was making his thanksgiving after Mass, Padre Pio had a vision of Jesus. When the vision ended, he had the stigmata in his hands, feet, and side.

Life became more complicated after that. Medical doctors, Church authorities, and curiosity seekers came to see Padre Pio. In 1924, and again in 1931, the authenticity of the stigmata was questioned; Padre Pio was not permitted to celebrate Mass publicly or to hear confessions. He did not complain of these decisions, which were soon reversed. However, he wrote no letters after 1924. His only other writing, a pamphlet on the agony of Jesus, was done before 1924.

Source of picture: https://nationalgeographicscans.tumblr.com

Padre Pio rarely left the friary after he received the stigmata, but busloads of people soon began coming to see him. Each morning after a 5 a.m. Mass in a crowded church, he heard confessions until noon. He took a mid-morning break to bless the sick and all who came to see him. Every afternoon he also heard confessions. In time his confessional ministry would take 10 hours a day; penitents had to take a number so that the situation could be handled. Many of them have said that Padre Pio knew details of their lives that they had never mentioned.

Padre Pio saw Jesus in all the sick and suffering. At his urging, a fine hospital was built on nearby Mount Gargano. The idea arose in 1940; a committee began to collect money. Ground was broken in 1946. Building the hospital was a technical wonder because of the difficulty of getting water there and of hauling up the building supplies. This “House for the Alleviation of Suffering” has 350 beds.

A number of people have reported cures they believe were received through the intercession of Padre Pio. Those who assisted at his Masses came away edified; several curiosity seekers were deeply moved. Like Saint Francis, Padre Pio sometimes had his habit torn or cut by souvenir hunters.

One of Padre Pio’s sufferings was that unscrupulous people several times circulated prophecies that they claimed originated from him. He never made prophecies about world events and never gave an opinion on matters that he felt belonged to Church authorities to decide. He died on September 23, 1968, and was beatified in 1999.

Source: https://www.franciscanmedia.org/saint-of-the-day/saint-pio-of-pietrelcina

#saints#St. Pio of Pietrelcina#priest#This is the most concrete synthesis of Padre Pio’s teaching#a privileged path of sanctity#House for the Alleviation of Suffering#The Gospel image of ‘yoke’ evokes the many trials that the humble Capuchin of San Giovanni Rotondo endured.#Today we contemplate in him how sweet is the ‘yoke’ of Christ and indeed how light the burdens are whenever someone carries these with faith#yoke#God#Jesus#Christ#Jesus Christ#Father#Son#Holy Spirit#Holy Trinity#christian religion#faith#hope#love#stress reliever

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good Jesu: what will you do with my heart?’

I have always loved the writings of the Carthusians and have found them to be be both beautiful and challenging. But recently I came across a homily given on the occasion of a jubilee celebration of a priest's ordination. The homily focuses on the love and commitment of Carthusians martyred under the reign of Henry VIII, in particular St. John Houghton. It speaks not only of the beauty of the priesthood and the sacraments but also what God can accomplish in hearts open to His love and grace. It speaks of the grace that is both needed and offered when we are faced with the difficult challenges and choices of life, no matter what our particular vocation may be. The following is a rather lengthy excerpt from the homily (one that I found deeply encouraging) and I hope you enjoy it:

“The story of the Carthusian martyrs is not as well known as it should be. No doubt this is because, in the great tale of the early English Reformation, the figures of Sts John Fisher and Thomas More tower over all others, for many and obvious good reasons. And yet nobody becomes a martyr without some extraordinary qualities—tenacity, faith, holiness—that make it possible to face all the consequences of simply doing the right thing when it is required. And yet how difficult that simple thing can be, even in small matters.

The monks of the London Charterhouse (who provided most of today’s saints) were renowned for their holiness of life in the early sixteenth century. It had become fashionable to grumble about monks at that time, but nobody grumbled about them. Thomas More, who could be rather scathing about monks who were no holier than they should be, actually lived with the London Carthusians for several years, and contemplated joining them. Carthusian monks, following a somewhat different and stricter form of the Benedictine life, have as their proud boast that they have never needed reform. Theirs is, and always has been, a very silent and recollected life: The London community in the sixteenth century was led by Prior John Houghton, a relatively young man, already with a reputation for sanctity. You will understand, then, why Henry VIII was particularly keen to get him and his community on side. Being widely respected, they would lend authority to the King’s claims to the headship of the Church in England.

When presented with the King’s demands that the London Carthusians recognize his claim to the headship of the Church in England, the community took three days to pray about it, on the last of which they celebrated a Mass of the Holy Spirit. During Mass, at the elevation, the whole community actually had an experience together that they unanimously identified as the Holy Spirit breathing in the chapel, and which gave them courage for what was to come—courage they would sorely need.

John Houghton, together with two other priors from the North, went to speak to Thomas Cromwell, the King’s strong arm man in religious matters. We can be sure that with his lawyer’s training, St John tried everything to make it possible to take the oath of allegiance to the King, without, however, compromising principle. Nothing availed, however, and all three were arrested, the charge being that —and I quote — ‘John Houghton says that he cannot take the King, our Sovereign Lord to be Supreme Head of the Church of England afore the apostles of Christ’s Church’, which rather makes it sound as if the apostles had also usurped what was the King’s rightful position.

In any event, he was condemned, of course—Cromwell had had to threaten the jury with treason charges themselves in order to achieve it, and the three priors together with a Bridgettine priest and a secular priest were all dragged to execution together. St Thomas More, by now in the Tower of London, watched them from the window of his cell setting off, and commented to his daughter who was visiting that they looked just like bridegrooms going to their wedding, a comparison that St John Fisher was also to use on the morning of his own death.

King Henry was insistent that the priests should be executed in their religious habits, to teach other religious a lesson, one presumes. This meant that after St John was cut down from the gallows, still alive, to be butchered, the thick hairshirt he wore under his heavy habit had to be cut through by the executioner, who had to stab down hard with the knife. And then, finally, as the executioner drew out St John’s still beating heart before his face, he spoke his last words: ‘Good Jesu’ he said, ‘what will you do with my heart?’

‘Good Jesu, what will you do with my heart?’ These are words that can speak to us at any stage, indeed in any moment in life, because we are daily confronted with choices between good and evil, or even simply between good and better. These words place the element of choice firmly in the Lord’s loving providence, praying for his grace to help us make the right decision.

When it comes to lifetime choices, however, St John Houghton’s words become more eloquent. There are any number of ways one can give ones life for the Lord—martyrdom is only one, albeit just about the best. One can also give ones living life for Him, by living in the married state, by working in any number of vocations in the world, and, of course, by spending ones life in consecrated religious life and/or the Priesthood. I think that the key element that identifies when a job becomes a vocation is when there is an element of self-giving to it—or in other words, when there is at least an element of martyrdom.

I have always been very struck by the story of Blessed Noel Pinot, a martyr of the French Revolution, who, having been arrested when about to celebrate Mass, ascended the scaffold to the guillotine dressed in the same Mass vestments, reciting to himself the same words we said today ‘Introibo ad altare Dei’. The mother of St John Bosco said to him on his ordination day; ‘remember, son, that beginning to say Mass means beginning to suffer’. These words come home to me and strike at my conscience, but I increasingly think that I can never really be worthy of my priesthood until I pour myself more entirely into it. There is nothing worth having that does not carry its price label, and the price label for following the Lord is imitating him in all things or, as He said Himself, taking up our cross daily. The question is not what do I want (the answer to that is straightforward: I’ll have an easy life, please, involving some nice dinners in agreeable company) but what does He want. In fact, ‘Good Jesu, what will you do with my heart?’ Because whereas my little wants are rather petty and contemptible, his are wonderful beyond comprehension. And very often beyond my comprehension, anyway.

Thanks be to God that the priesthood of God’s Church does not belong to me but to Christ, that I do not exercise it, but he exercises it through me. Thanks be to God that the sacraments we offer do not depend on our worthiness but on His.

What a wonder it is that the Lord loves us at all! And yet he does, and is happy with the feeble struggle and great labour we make of bearing his sweet and gentle yoke, he rejoices as a parent does when guiding the first steps of a child or when speaking his first words. Caused by grace, these shallow twitches in our lives towards doing the Lord’s will and setting aside our own desires are no matters of mere jubilees and quarter centuries, they are the stuff of eternity leaking into time. These things are signs of the Kingdom of God, where, in eternity, eye has not seen nor ear heard what good things God prepares for those who love him. Which is why we pray with St John Houghton: ‘Good Jesu: what will you do with my heart?’”

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Thought for the Day – The Memorial of St Padre Pio (1887-1968)

There can be no doubt that Padre Pio dedicated his life to prayer and suffering. Every breath he took was a prayer—never for himself, always for others. From the beginning of his life, he was able to easily travel from this world to the next, through deep prayer. He used this connection with God to recommend to him the prayers of his spiritual children. This ability to make contact with the powerful presence of God through prayer enabled him to bless and pray with those in most need, wherever they were in the world. Padre Pio in prayer visited South America, the United States and parts of Europe. Those he visited would know that Padre Pio was present by the unmistakable aroma of violets and roses. Those who got closest to him noticed an odour of flowers emanating from the stigmata. To this day, forty-six years after his death, people will still insist that they have caught the scent of roses after praying for someone through the intercession of Padre Pio.

Padre Pio’s priority was to be simply “a friar who prays.” His intense prayer was offered up day and night for all his spiritual children and his religious community. He had a filial love for our Blessed Lady and spent much of his day praying the rosary. But Padre Pio was first and foremost a brother to the Capuchin Franciscan community of Our Lady of Graces friary. Like the others, he daily lived the rule and life of the Order of Friars Minor. The first chapter of the rule of Saint Francis outlines that the rule is simply to observe the Gospel of Jesus Christ, living in obedience and in chastity, without property. As a Capuchin Franciscan, he promised obedience and reverence to the pope and to his superiors in the Capuchin order. No doubt it pained him greatly when the cult of sanctity built up around him, causing difficulties for the order with Church authorities.

Shortly before he died, the stigmata began to heal. When his body was examined by the doctors, they found that fresh, white skin had grown over the healed wounds. His life on earth was over, his earthly sufferings endured. He was journeying to the house of the Father where he prays for us all today in the presence of God.

Referring to that day’s Gospel (Matthew 11:25-30) at Padre Pio’s canonisation Mass in 2002, Saint John Paul II said: “The Gospel image of ‘yoke’ evokes the many trials that the humble Capuchin of San Giovanni Rotondo endured. Today we contemplate in him how sweet is the ‘yoke’ of Christ and indeed how light the burdens are whenever someone carries these with faithful love. The life and mission of Padre Pio testify that difficulties and sorrows, if accepted with love, transform themselves into a privileged journey of holiness, which opens the person toward a greater good, known only to the Lord.”

St Padre Pio pray for us

(via AnaStpaul – Breathing Catholic)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good Jesu: what will you do with my heart?’

I have always loved the writings of the Carthusians and have found them to be be both beautiful and challenging. But recently I came across a homily given on the occasion of a jubilee celebration of a priest's ordination. The homily focuses on the love and commitment of Carthusians martyred under the reign of Henry VIII, in particular St. John Houghton. It speaks not only of the beauty of the priesthood and the sacraments but also what God can accomplish in hearts open to His love and grace. It speaks of the grace that is both needed and offered when we are faced with the difficult challenges and choices of life, no matter what our particular vocation may be. The following is a rather lengthy excerpt from the homily (one that I found deeply encouraging) and I hope you enjoy it:

“The story of the Carthusian martyrs is not as well known as it should be. No doubt this is because, in the great tale of the early English Reformation, the figures of Sts John Fisher and Thomas More tower over all others, for many and obvious good reasons. And yet nobody becomes a martyr without some extraordinary qualities—tenacity, faith, holiness—that make it possible to face all the consequences of simply doing the right thing when it is required. And yet how difficult that simple thing can be, even in small matters.

The monks of the London Charterhouse (who provided most of today’s saints) were renowned for their holiness of life in the early sixteenth century. It had become fashionable to grumble about monks at that time, but nobody grumbled about them. Thomas More, who could be rather scathing about monks who were no holier than they should be, actually lived with the London Carthusians for several years, and contemplated joining them. Carthusian monks, following a somewhat different and stricter form of the Benedictine life, have as their proud boast that they have never needed reform. Theirs is, and always has been, a very silent and recollected life: The London community in the sixteenth century was led by Prior John Houghton, a relatively young man, already with a reputation for sanctity. You will understand, then, why Henry VIII was particularly keen to get him and his community on side. Being widely respected, they would lend authority to the King’s claims to the headship of the Church in England.

When presented with the King’s demands that the London Carthusians recognize his claim to the headship of the Church in England, the community took three days to pray about it, on the last of which they celebrated a Mass of the Holy Spirit. During Mass, at the elevation, the whole community actually had an experience together that they unanimously identified as the Holy Spirit breathing in the chapel, and which gave them courage for what was to come—courage they would sorely need.

John Houghton, together with two other priors from the North, went to speak to Thomas Cromwell, the King’s strong arm man in religious matters. We can be sure that with his lawyer’s training, St John tried everything to make it possible to take the oath of allegiance to the King, without, however, compromising principle. Nothing availed, however, and all three were arrested, the charge being that —and I quote — ‘John Houghton says that he cannot take the King, our Sovereign Lord to be Supreme Head of the Church of England afore the apostles of Christ’s Church’, which rather makes it sound as if the apostles had also usurped what was the King’s rightful position.

In any event, he was condemned, of course—Cromwell had had to threaten the jury with treason charges themselves in order to achieve it, and the three priors together with a Bridgettine priest and a secular priest were all dragged to execution together. St Thomas More, by now in the Tower of London, watched them from the window of his cell setting off, and commented to his daughter who was visiting that they looked just like bridegrooms going to their wedding, a comparison that St John Fisher was also to use on the morning of his own death.

King Henry was insistent that the priests should be executed in their religious habits, to teach other religious a lesson, one presumes. This meant that after St John was cut down from the gallows, still alive, to be butchered, the thick hairshirt he wore under his heavy habit had to be cut through by the executioner, who had to stab down hard with the knife. And then, finally, as the executioner drew out St John’s still beating heart before his face, he spoke his last words: ‘Good Jesu’ he said, ‘what will you do with my heart?’

‘Good Jesu, what will you do with my heart?’ These are words that can speak to us at any stage, indeed in any moment in life, because we are daily confronted with choices between good and evil, or even simply between good and better. These words place the element of choice firmly in the Lord’s loving providence, praying for his grace to help us make the right decision.

When it comes to lifetime choices, however, St John Houghton’s words become more eloquent. There are any number of ways one can give ones life for the Lord—martyrdom is only one, albeit just about the best. One can also give ones living life for Him, by living in the married state, by working in any number of vocations in the world, and, of course, by spending ones life in consecrated religious life and/or the Priesthood. I think that the key element that identifies when a job becomes a vocation is when there is an element of self-giving to it—or in other words, when there is at least an element of martyrdom.

I have always been very struck by the story of Blessed Noel Pinot, a martyr of the French Revolution, who, having been arrested when about to celebrate Mass, ascended the scaffold to the guillotine dressed in the same Mass vestments, reciting to himself the same words we said today ‘Introibo ad altare Dei’. The mother of St John Bosco said to him on his ordination day; ‘remember, son, that beginning to say Mass means beginning to suffer’. These words come home to me and strike at my conscience, but I increasingly think that I can never really be worthy of my priesthood until I pour myself more entirely into it. There is nothing worth having that does not carry its price label, and the price label for following the Lord is imitating him in all things or, as He said Himself, taking up our cross daily. The question is not what do I want (the answer to that is straightforward: I’ll have an easy life, please, involving some nice dinners in agreeable company) but what does He want. In fact, ‘Good Jesu, what will you do with my heart?’ Because whereas my little wants are rather petty and contemptible, his are wonderful beyond comprehension. And very often beyond my comprehension, anyway.

Thanks be to God that the priesthood of God’s Church does not belong to me but to Christ, that I do not exercise it, but he exercises it through me. Thanks be to God that the sacraments we offer do not depend on our worthiness but on His.

What a wonder it is that the Lord loves us at all! And yet he does, and is happy with the feeble struggle and great labour we make of bearing his sweet and gentle yoke, he rejoices as a parent does when guiding the first steps of a child or when speaking his first words. Caused by grace, these shallow twitches in our lives towards doing the Lord’s will and setting aside our own desires are no matters of mere jubilees and quarter centuries, they are the stuff of eternity leaking into time. These things are signs of the Kingdom of God, where, in eternity, eye has not seen nor ear heard what good things God prepares for those who love him. Which is why we pray with St John Houghton: ‘Good Jesu: what will you do with my heart?’”

9 notes

·

View notes