#a non-explanation whose function is to moralize rather than understand

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

There's several incredibly easy criticisms, but I feel the concept of "corporate greed" becomes particularly incoherent when used to explain the prices of something having only just now gone up

you think corporations only invented greed last week and simply had not thought to raise prices anytime earlier?

#economics#greed#'greed' is for leftists basically what 'laziness' is for authoritarians#a non-explanation whose function is to moralize rather than understand#hm also that's two “deadly sins”. lessee if we can rope more of them into this#'lust' yeah is kind of a boogeyman of conservatives#'wrath' / 'hate' a boogeyman of… anyone too deep into politics#pride-as-a-boogeyman = Law of Jante#gluttony-as-a-boogeyman = naïve fatphobia and some weirder types of anti-consumerism#idk envy. honestly I think envy might actually exist

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sex Education Pamphlet That Sparked a Landmark Censorship Case

https://sciencespies.com/history/the-sex-education-pamphlet-that-sparked-a-landmark-censorship-case/

The Sex Education Pamphlet That Sparked a Landmark Censorship Case

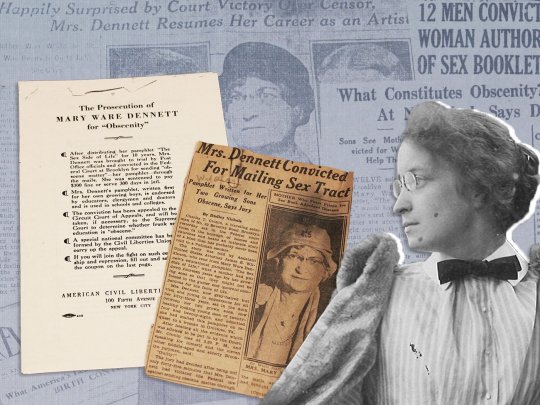

Mary Ware Dennett wrote The Sex Side of Life in 1915 as a teaching tool for her teenage sons. Photo illustration by Meilan Solly / Photos courtesy of Sharon Spaulding and Newspapers.com

It only took 42 minutes for an all-male jury to convict Mary Ware Dennett. Her crime? Sending a sex education pamphlet through the mail.

Charged with violating the Comstock Act of 1873—one of a series of so-called chastity laws—Dennett, a reproductive rights activist, had written and illustrated the booklet in question for her own teenage sons, as well as for parents around the country looking for a new way to teach their children about sex.

Lawyer Morris Ernst filed an appeal, setting in motion a federal court case that signaled the beginning of the end of the country’s obscenity laws. The pair’s victory marked the zenith of Dennett’s life work, building on her previous efforts to publicize and increase access to contraception and sex education. (Prior to the trial, she was best known as the more conservative rival of Margaret Sanger, founder of Planned Parenthood.) Today, however, United States v. Dennett and its defendant are relatively unknown.

“One of the reasons the Dennett case hasn’t gotten the attention that it deserves is simply because it was an incremental victory, but one that took the crucial first step,” says Laura Weinrib, a constitutional historian and law scholar at Harvard University. “First steps are often overlooked. We tend to look at the culmination and miss the progression that got us there.”

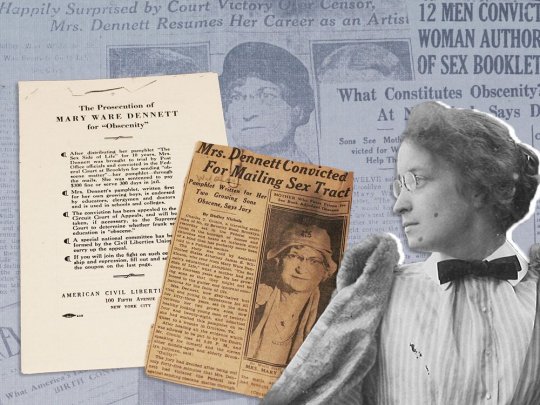

Dennett wrote the offending pamphlet (in blue) for her two sons.

Sharon Spaulding / Dennett Family Archive

Dennett wrote the pamphlet in question, The Sex Side of Life: An Explanation for Young People, in 1915. Illustrated with anatomically correct drawings, it provided factual information, offered a discussion of human physiology and celebrated sex as a natural human act.

“[G]ive them the facts,” noted Dennett in the text, “… but also give them some conception of sex life as a vivifying joy, as a vital art, as a thing to be studied and developed with reverence for its big meaning, with understanding of its far-reaching reactions, psychologically and spiritually.”

After Dennett’s 14-year-old son approved the booklet, she circulated it among friends who, in turn, shared it with others. Eventually, The Sex Side of Life landed on the desk of editor Victor Robinson, who published it in his Medical Review of Reviewsin 1918. Calling the pamphlet “a splendid contribution,” Robinson added, “We know nothing that equals Mrs. Dennett’s brochure.” Dennett, for her part, received so many requests for copies that she had the booklet reprinted and began selling it for a quarter to anyone who wrote to her asking for one.

These transactions flew in the face of the Comstock Laws, federal and local anti-obscenity legislation that equated birth control with pornography and rendered all devices and information for the prevention of conception illegal. Doctors couldn’t discuss contraception with their patients, nor could parents discuss it with their children.

Dennett as a young woman

Sharon Spaulding / Dennett Family Archive

The Sex Side of Life offered no actionable advice regarding birth control. As Dennett acknowledged in the brochure, “At present, unfortunately, it is against the law to give people information as to how to manage their sex relations so that no baby will be created.” But the Comstock Act also stated that any printed material deemed “obscene, lewd or lascivious”—labels that could be applied to the illustrated pamphlet—was “non-mailable.” First-time offenders faced up to five years in prison or a maximum fine of $5,000.

In the same year that Dennett first wrote the brochure, she co-founded the National Birth Control League (NBCL), the first organization of its kind. The group’s goal was to change obscenity laws at a state level and unshackle the subject of sex from Victorian morality and misinformation.

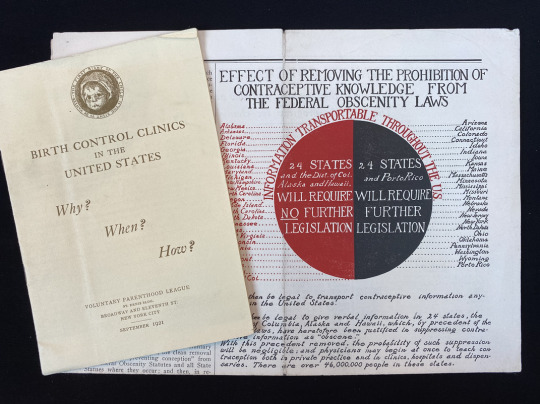

By 1919, Dennett had adopted a new approach to the fight for women’s rights. A former secretary for state and national suffrage associations, she borrowed a page from the suffrage movement, tackling the issue on the federal level rather than state-by-state. She resigned from the NBCL and founded the Voluntary Parenthood League, whose mission was to pass legislation in Congress that would remove the words “preventing conception” from federal statutes, thereby uncoupling birth control from pornography.

Dennett soon found that the topic of sex education and contraception was too controversial for elected officials. Her lobbying efforts proved unsuccessful, so in 1921, she again changed tactics. Though the Comstock Laws prohibited the dissemination of obscene materials through the mail, they granted the postmaster general the power to determine what constituted obscenity. Dennett reasoned that if the Post Office lifted its ban on birth control materials, activists would win a partial victory and be able to offer widespread access to information.

Postmaster General William Hays, who had publicly stated that the Post Office should not function as a censorship organization, emerged as a potential ally. But Hays resigned his post in January 1922 without taking action. (Ironically, Hays later established what became known as the Hays Code, a set of self-imposed restrictions on profanity, sex and morality in the motion picture industry.) Dennett had hoped that the incoming postmaster general, Hubert Work, would fulfill his predecessor’s commitments. Instead, one of Work’s first official actions was to order copies of the Comstock Laws prominently displayed in every post office across America. He then declared The Sex Side of Life “unmailable” and “indecent.”

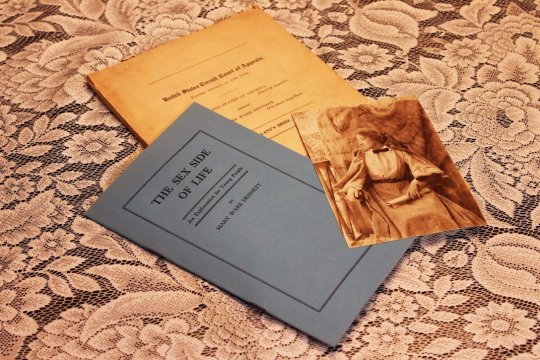

Mary Ware Dennett, pictured in the 1940s

Dennett Family Archive

Undaunted, Dennett redoubled her lobbying efforts in Congress and began pushing to have the postal ban on her booklet removed. She wrote to Work, pressing him to identify which section was obscene, but no response ever arrived. Dennett also asked Arthur Hays, chief counsel of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), to challenge the ban in court. In letters preserved at Radcliffe College’s Schlesinger Library, Dennett argued that her booklet provided scientific and factual information. Though sympathetic, Hays declined, believing that the ACLU couldn’t win the case.

By 1925, Dennett—discouraged, broke and in poor health—had conceded defeat regarding her legislative efforts and semi-retired. But she couldn’t let the issue go entirely. She continued to mail The Sex Side of Life to those who requested copies and, in 1926, published a book titled Birth Control Laws: Shall We Keep Them, Change Them, or Abolish Them?

Publicly, Dennett’s mission was to make information about birth control legal; privately, however, her motivation was to protect other women from the physical and emotional suffering she had endured.

The activist wed in 1900 and gave birth to three children, two of whom survived, within five years. Although the specifics of her medical condition are unknown, she likely suffered from lacerations of the uterus or fistulas, which are sometimes caused by childbirth and can be life-threatening if one becomes pregnant again.

Without access to contraceptives, Dennett faced a terrible choice: refrain from sexual intercourse or risk death if she conceived. Within two years, her husband had left her for another woman.

Dennett obtained custody of her children, but her abandonment and lack of access to birth control continued to haunt her. Eventually, these experiences led her to conclude that winning the vote was only one step on the path to equality. Women, she believed, deserved more.

In 1928, Dennett again reached out to the ACLU, this time to lawyer Ernst, who agreed to challenge the postal ban on the Sex Side of Life in court. Dennett understood the risks and possible consequences to her reputation and privacy, but she declared herself ready to “take the gamble and be game.” As she knew from press coverage of her separation and divorce, newspaper headlines and stories could be sensational, even salacious. (The story was considered scandalous because Dennett’s husband wanted to leave her to form a commune with another family.)

Dennett cofounded the National Birth Control League, the first organization of its kind in the U.S., in 1915. Three years later, she launched the Voluntary Parenthood League, which lobbied Congress to change federal obscenity laws.

Sharon Spaulding / Dennett Family Archive

“Dennett believed that anyone who needed contraception should get it without undue burden or expense, without moralizing or gatekeeping by the medical establishment,” says Stephanie Gorton, author of Citizen Reporters: S.S. McClure, Ida Tarbell and the Magazine That Rewrote America. “Though she wasn’t fond of publicity, she was willing to endure a federal obscenity trial so the next generation could have accurate sex education—and learn the facts of life without connecting them with shame or disgust.”

In January 1929, before Ernst had finalized his legal strategy, Dennett was indicted by the government. Almost overnight, the trial became national news, buoyed by The Sex Side of Life’s earlier endorsement by medical organizations, parents’ groups, colleges and churches. The case accomplished a significant piece of what Dennett had worked 15 years to achieve: Sex, censorship and reproductive rights were being debated across America.

During the trial, assistant U.S. attorney James E. Wilkinson called the Sex Side of Life “pure and simple smut.” Pointing at Dennett, he warned that she would “lead our children not only into the gutter, but below the gutter and into the sewer.”

None of Dennett’s expert witnesses were allowed to testify. The all-male jury took just 45 minutes to convict. Ernst filed an appeal.

In May, following Dennett’s conviction but prior to the appellate court’s ruling, an investigative reporter for the New York Telegram uncovered the source of the indictment. A postal inspector named C.E. Dunbar had been “ordered” to investigate a complaint about the pamphlet filed by an official with the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). Using the pseudonym Mrs. Carl Miles, Dunbar sent a decoy letter to Dennett requesting a copy of the pamphlet. Unsuspecting, Dennett mailed the copy, thereby setting in motion her indictment, arrest and trial. (Writing about the trial later, Dennett noted that the DAR official who allegedly made the complaint was never called as a witness or identified. The activist speculated, “Is she, perhaps, as mythical as Mrs. Miles?”)

Dennett’s is a name that deserves to be known.

When news of the undercover operation broke, Dennett wrote to her family that “support for the case is rolling up till it looks like a mountain range.” Leaders from the academic, religious, social and political sectors formed a national committee to raise money and awareness in support of Dennett; her name became synonymous with free speech and sex education.

In March 1930, an appellate court reversed Dennett’s conviction, setting a landmark precedent. It wasn’t the full victory Dennett had devoted much of her life to achieving, but it cracked the legal armor of censorship.

“Even though Mary Ware Dennett wasn’t a lawyer, she became an expert in obscenity law,” says constitutional historian Weinrib. “U.S. v. Dennett was influential in that it generated both public enthusiasm and money for the anti-censorship movement. It also had a tangible effect on the ACLU’s organizational policies, and it led the ACLU to enter the fight against all forms of what we call morality-based censorship.”

Ernst was back in court the following year. Citing U.S. v. Dennett, he won two lawsuits on behalf of British sex educator Marie Stopes and her previously banned books, Married Love and Contraception. Then, in 1933, Ernst expanded on arguments made in the Dennett case to encompass literature and the arts. He challenged the government’s ban on James Joyce’s Ulysses and won, in part because of the precedent set by Dennett’s case. Other important legal victories followed, each successively loosening the legal definition of obscenity. But it was only in 1970 that the Comstock Laws were fully struck down.

Ninety-two years after Dennett’s arrest, titles dealing with sex continue to top the list of the American Library Association’s most frequently challenged books. Sex education hasn’t fared much better. As of September 2021, only 18 states require sex education to be medically accurate, and only 30 states mandate sex education at all. The U.S. has one of the highestteen pregnancy rates of all developed nations.

What might Dennett think or do if she were alive today? Lauren MacIvor Thompson, a historian of early 20th-century women’s rights and public health at Kennesaw State University, takes the long view:

While it’s disheartening that we are fighting the same battles over sex and sex education today, I think that if Dennett were still alive, she’d be fighting with school boards to include medically and scientifically accurate, inclusive, and appropriate information in schools. … She’d [also] be fighting to ensure fair contraceptive and abortion access, knowing that the three pillars of education, access and necessary medical care all go hand in hand.

At the time of Dennett’s death in 1947, The Sex Side of Life had been translated into 15 languages and printed in 23 editions. Until 1964, the activist’s family continued to mail the pamphlet to anyone who requested a copy.

“As a lodestar in the history of marginalized Americans claiming bodily autonomy and exercising their right to free speech in a cultural moment hostile to both principles,” says Gorton, “Dennett’s is a name that deserves to be known.”

Activism

Censorship

Law

Sex

Sexuality

Women’s History

Women’s Rights

Women’s Suffrage

#History

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

re: the relativism thing – ultimately it’s not too important whether or not the arguments for moral relativism/subjectivism are convincing to any one person. if it’s true, it’s true whether or not it’s believed, and in any case, it’s just another ‘is’ from which no ‘ought’ can be derived – obviously, in a society whose mores permit slavery, slavery is moral, but just as obviously there’s no reason not to try to stop people from owning slaves. I may believe it to be true, but it should go without saying that were I to be kidnapped and brought to some secluded basement to await an interesting variety of tortures before a miserable death, I would of course lie through my teeth to my captor to warn her that God would punish her for the ‘objectively’ evil things she was about to do to me, even if she were never caught by the authorities.

it’s therefore for purely practical, and subjective, reasons that I want the belief in relativism spread, and it’s only a convenient accident that I believe it to be true. a widespread belief in relativism will demoralize, weaken, and strip support from the Left/Progressivism/Western institutions/cultural norms, while empowering its (sic) enemies.

ridiculous as it sounds, and is, Progressives/Westerners continue to believe that everyone in the world is trying to achieve their values (equality, unity); indeed, that others who aren’t them are more successfully living up to their values than they themselves. this belief is difficult to maintain in the face of the overwhelming evidence that no one else cares about their ideals, and merely pays lip service to them because of their money and/or guns, so they are understandably thrilled at the slightest hint that it could be true. (‘one of the greatest events in the history of humanity! *sczhniff* the stupid savages finally stopped going back to their barbaric ways and did what we told them they should have wanted all along!’) but it should be said, for once, clearly: nobody, including them, values everyone equally, and nobody, except for them, wants to. will the Left/West (I’m not going to justify the forward slash here, but it is justified imo, at least tactically) be willing to impose what it wants at gun-point, without any illusions that it is acting on anyone’s behalf, knowingly disregarding what its victims want, and want to want? luckily, this question is irrelevant, because nothing will be left up to Western decency: “the West won the world not by the superiority of its ideas or values or religion but rather by the superiority in applying organized violence”; and now everyone else is well armed too. (the correct, and immanent, answer to the question ‘when will China democratize?’ is gunfire.) importantly though, with no illusions that it is enforcing a universalist ethic for anyone’s benefit but its own, the West will be demoralized, and more likely to fail.

but the Left/West is particularly vulnerable to relativist/subjectivist corrosion not only because it frames its project in universal terms, but because it itself uses the logic of determinism, cultural or historical, as a weapon:

The psychological benefits of this absolutist relativism are real, if a little hard to describe. Part of the [post-Protestants’] elevation of non-Western cultures derives from the useful way the sheer existence of these cultures can be used to disparage other American classes. And part of it undoubtedly descends from the old Romantic view of primitive life as being more authentic and spiritually rich. But a great emotional gift of post-Protestantism, at least one of the strong feelings of self-esteem it bestows on its class members, is the constant sense of superiority—intellectual superiority, in this case, not necessarily in the sense of genuinely being smarter, but in the sense that they can say to themselves, ‘We have cultural, social, and economic explanations for others, while they have no explanation for us.’ (Joseph Bottum, An Anxious Age)

and has a tradition of suspicion of the ‘structural forces’ and ‘false consciousness’ operating in society. how awkward, then, that we do in fact have cultural, social, and economic explanations for them (the genealogical critique of Progressivism as a direct descendent from protestant Christianity, most prominently [recently] from Moldbug, but certainly not originating with/exclusive to him), and that they and their enemies

may disagree on everything, but Structural Suspicion treats them as functionally and morally equivalent. Both are Foucault’s “standardized products,” presorted by society and received accordingly. This is the subterranean aporia of Moralist ideology: plagued by Suspicion, unable to ground itself in impeccable authenticity, its Ethical victories are hollow. In such a vision, Moralist activism can come to seem like a frustrating joke, as Kameron Hurley discovered. If your Theoretical background tells you that your place in society is not under your control and your own motives are suspect and meaningless, your activist practice will be plagued by self-doubt and you may turn your Suspicion into a self-fulfilling prophecy. (x)

already the enemy has a presentiment of what is coming, or rather, what has just begun to arrive. see eg this post, dripping with dramatic irony:

gotta say i’m real glad the discourse has broken firmly toward the side of “slavery is always wrong, regardless of cultural relativism,” because wow things could have gone down a very different much worse path

(– as if ‘the discourse’ were still exhausted by the opinions of a few thousand Western Tumblr users!)

Progressivism must rule; its enemies have only to prevent that. relativism/subjectivism can help us to do so by destroying its will to enforce itself, by emboldening its enemies to see their resistance to Progressivism not as a necessary evil but as a positive good, and by dismantling even the tenuous basis universalism has in reality by encouraging all those trends tending to separation, fragmentation, and soon, speciation.

before you felt powerless before the problems facing the world, facing Humanity, but perhaps you should ask yourself: is it really any of your business? you’ve been instructed to, but do you really care about Humanity? I doubt it.

The shame of seeing one’s own impotence laid bare can also feel like a relief: unshouldering the burden of Universal Progress, we make room for a secret desire to flourish. (x)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Easter thoughts

My mom and I were talking about movies about Jesus last week, and she mentioned that one of her problems with The Passion of the Christ was that it didn't include much in the way of miracles. Without miracles, she reasoned, the movie offered no real explanation to people who weren't already Christian as to why the cross was such an important symbol in our faith.

My immediate response was that I thought the movie had intentionally chosen such a narrow focus that I couldn't see why people who weren't already Christian would go to it expecting to receive those kinds of answers (as opposed to going out of sheer morbid curiosity towards one of the most violent movies ever made).

As for miracles, I said, I didn't think including them would have done much to answer the question at hand. Miracles might explain why Christians believe Jesus is God. They offer no explanation as to how we went from "Jesus is God" to "therefore, we should hang the likeness of His corpse in all of our sacred spaces."

If there's one thing The Passion of the Christ deserves credit for, it's pushing people towards a much greater consideration of the historical context implicit in (but not specified by) the Passion narrative.

That wasn't what the movie was going for, of course, at least with regards to political context. It drew well-warranted criticism for its failure to engage with the complex relationship between the political expediency of a brutal Roman tyrant, the self-preservation of a Temple hierarchy that perceived Jesus as an existential threat, and the potential powder keg posed by a massive-if-temporary influx of pilgrims whose loyalties were so divided with regards to Jesus that any move made by either Pilate or the Temple could result in disaster for everyone involved.

But, while the movie might not have suffered financially for this failure, the criticism it received was so loud (and the vindication of said criticism so impossible to ignore) that it's no longer possible for someone to simplify the Passion narrative in good faith. As such, more recent filmed retellings seem to bring the political maneuvering to the forefront.

(Incidentally, given the degree to which morally-questionable political maneuvering has come in vogue in recent years, there's no reason not to go there nowadays, regardless of how much money black-and-white morality might have made back in 2004.)

Anyway, what The Passion of the Christ seemed to want, more than anything, was to convict the audience with its violence. Rather than portray Jesus' crucifixion as solemn and sorrowful, it presented it as brutal, sadistic, and repulsive. And, when presented with two hours of film centered on the horrific torture of God-made-flesh, major religious figures came out to say not only that such a portrayal wasn't sacrilegious, but also that the movie was basically on the right track in choosing to frame the Crucifixion that way.

That, I think, is the movie's real legacy. Realistically depicting the Crucifixion in visual media now demands a commitment to portraying a bloody, agonizing horror, even if one is aiming for a PG-13 rating rather than Gibson's hard R. I was surprised by how graphic Son of God got, for instance, not just because the TV station airing it apparently thought it could pass as PG-V (which is patently absurd), but also because its method of handling its theatrical PG-13 limitation seems to have been to ditch all of the gore and trade explicitly sadistic torturers for a much more banal depiction of evil, while retaining as much blood as possible and focusing on physical and mental vulnerability over heroic resilience*.

And, bizarrely, while it's been less than a decade and a half since footage of that sort became acceptable in Jesus films, it has apparently become difficult for some people to imagine properly understanding Christianity without it. For example, in response to the existence of content warnings for such footage in college theology courses, I’ve seen comments that are more along the lines of, "Of course crucifixion looks traumatic and horrifying on film. What did you expect?" than the usual "How could anyone be traumatized by that?" reaction.

What's even weirder is that there... might actually be some truth to that? I'm of the opinion that those inclined to take advantage of such a warning are probably well aware of the principle that such films are designed to show, but there's still nothing quite as effective as a blood-soaked actor simulating the throes of mortal agony to remind one that the cross was originally intended to serve as an instrument of torture and terror.

* I don't know whether Gibson intended it this way, but it feels like he let his association with action heroes who withstand impossible amounts of torture bleed into his take on Jesus, both in the way He crushes all hesitation and doubt right at the beginning and in His ability to force His body to obey in spite of the abuse to which He is subjected. Son of God's portrayal of the Crucifixion drew a ton of influence from Gibson's in other respects, but reversing this one element -- allowing the conflict between the weak flesh and the willing spirit to result in fear and humiliation rather than serve as an occasion to demonstrate strength -- resulted in a very different effect.

So, let's get back to the original question: why would a major world religion make the cross all but ubiquitous? What value is there in choosing a representation of God as a humiliated, tortured corpse to serve as the primary association outsiders have with Christianity, especially given the strict prohibition against images and likenesses in the tradition from which Christianity was drawn?

I think, to some extent, the reason why that transition happened was because the cross already was a graven image -- not a permanent fixture intended to represent a god, of course, but an image of imperial domination graven into the all-too-impermanent flesh of its enemies.

In a sense, the cross operates under a sort of turn-the-other-cheek logic. When granted political authority over God-in-the-flesh, humanity turned His body into an idol to their temporal power -- and, rather than retaliate, God raised that idol up and offered humanity its continued use, transforming it into a permanent indictment of human nature in the process. Moreover, as salvation took the form of a subversion of the height of human depravity (the most agonizing and humiliating form of torture in use at the time), it became impossible to portray the nature of said salvation without acknowledging said depravity. Taking the cross as a symbol means condemning ourselves, and in that self-condemnation can be found non-retributive justice.

There's also a sense in which the Christian use of the cross is a transformation of abusive propaganda into hardcore performance art -- something akin to providing image board trolls with an opportunity to mark their inevitable filth on one's naked body to uncover their shameful behavior, albeit taken to the nth power. In the context of initial persecution, that transformation subverted attempts to terrorize Christians and turned the deaths of martyrs into willing imitations of the original performance, spreading further awareness of the depths of human depravity and its inability to carry the day. And, once the persecution stopped, it’s only natural that the original performance would be depicted as frequently as possible to ensure that its message wouldn’t be forgotten.

It’s utterly brilliant in a way practically no one 2,000 years ago -- for whom non-retributive justice and performance art would have been as alien as smartphones -- could have even hoped to understand, but that didn’t stop the imagery from spreading like wildfire.

Of course, replicating imagery without full awareness of its function risks losing something critical, and that’s where I think the recent trend of brutal crucifixion scenes actually serves as something of a corrective. Self-sacrificial love can be portrayed without drawing too much attention to the subject as a corpse (particularly among people who grew up surrounded by such symbols), but that just calls into question why the cross imagery is used in the first place. It’s only in the shock and horror evoked by an explicit depiction of Jesus’ brutal and humiliating death by crucifixion that the purpose of prioritizing the cross can be fully understood.

#Easter#Good Friday#The Passion of the Christ#Son of God movie#Christianity#Disclaimer: I am a layperson and speak with no real authority#I've just been thinking about this sort of stuff a lot recently#Crucifixion for ts

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

NATIONALISM AND XENOPHOBIA, REDUX

Morgan Marietta’s and Will Wilkinson’s replies to my essay on nationalism could hardly be more different. The differences bear not only on how we account for Donald Trump’s surprising political success, but on the purposes and procedures of social science.

Like my essay, Marietta’s extends the principle of interpretive charity to Trump supporters. In my view, interpretive charity should be the first principle of social science. If anything, however, I think that Marietta takes interpretive charity a bit too far by endorsing nationalist sentiments as morally legitimate. It’s true that if we use interpretive charity to try to understand ideas with which we disagree, we might become proponents of those ideas. Indeed, one of the advantages of interpretive charity is that it can change our minds. Conversely, if a scholar of nationalism, for example, fails to agree with the ideas of nationalists, it seems at least possible that this is because he has failed to understand those ideas. If I really comprehended why you believe X, I would have to understand all the considerations that led you to believe X, and I’d have to understand them in the same way you do. But, having achieved this mind meld, shouldn’t I, too, believe X?

Not necessarily. I may know of counter-arguments against X that you don’t know about, and these may lead me to disagree with X even when I completely understand your reasons for agreeing with it.

I think this is the case with nationalist beliefs. One can be fully charitable toward these beliefs even while noticing that they tend to be inculcated very early, among children, through symbols (such as the national flag) and biased information samples (such as the media’s massive overweighting of attention to the citizens of one’s own cfdountry rather than people who live elsewhere). By the time someone is capable of thinking critically about her own nationalist assumptions, she may find it hard even to identify them—and unnecessary, too, since everyone around her will tend to take the same assumptions for granted.

Thus, while I argued, in the spirit of interpretive charity, that nationalism is distinct from xenophobia, I also maintained, and continue to maintain, that nationalism is morally indefensible: most nationalists have simply failed to think about the arbitrariness of the group loyalties that were pre-rationally constructed for them long ago.

Interpretive charity is not Wilkinson’s project. He argues that a significant proportion of Trump supporters are xenophobes beholden to an irrational hostility to foreigners. I’m suspicious of such explanations because they tend to demonize “the other”—in Wilkinson’s case, Trump supporters—which is exactly what Wilkinson accuses Trump supporters of doing (when it comes to foreigners).

Demonization amounts to a confession that one has failed to understand the other on his or her own terms. This usually means that social science has failed. Not always, though. It’s possible, in a given case, that people’s behavior or their ideas are so irrational that they can be explained only by appealing to influences of which they are unaware, and which they would deny if they were asked about them. In such cases, we may need “deep” psychological theories to explain “the other.” Like the authoritarian-personality theory of Trump’s support, which I discussed in my last post, the xenophobia theory posits a subterranean psychological force that has erupted in the form of Trumpism.

This isn’t inherently unbelievable, but the evidence for it is weak; and there is strong evidence against it. My essay advanced nationalism as an alternative to xenophobia in partial explanation of Trump’s support. Nationalism fits the available evidence better, and it’s interpretively charitable. A good test of interpretive charity is whether those whose actions or beliefs you’re trying to explain could accept your explanation. It’s doubtful that many Trump supporters would accept Wilkinson’s explanation of their actions and beliefs, but they would probably accept the nationalism explanation. For this explanation suggests that support for Trump is consistent with the “commonsensical” nationalist presuppositions of everyday politics. The xenophobia theory, in contrast, is not only interpretively uncharitable and weak in evidentiary terms, but it conveniently locates Trumpism far away from the “liberal” traditions of everyday politics—where it can safely be vilified without threatening the status quo./span>

Trump as Deep Nationalist

Marietta’s essay begins by underscoring the fact that Trump constantly and unreflectively appeals to the interests of “America” as the supreme good. Marietta is willing to call the basis of these appeals an ideology: “deep nationalism.” By this, Marietta means that Trump’s nationalism is the prism through which he seems to view nearly every policy issue—at least those issues in which he takes an interest.

The four most important of these are immigration, U.S. relationships with foreign allies, military policy, and international trade. All one need do is listen to what Trump says, as Marietta has done, to discover a connective ideological thread among these issues: nationalism. At the same time, Trump’s “deep nationalism” explains his lack of interest in a host of policy issues that preoccupy conservative and liberal ideologues, such as Obamacare, the minimum wage, regulatory policy, global warming, income inequality, tax rates, etc., ad infinitum. These latter issues do not easily lend themselves to “America-first” analyses, and thus are not clarified by the deep nationalist lens through which Trump (and, both Marietta and I suggest, many of his supporters) view politics.

I think Marietta is making an excellent point. Nationalism does seem to function for Trump in an ideological manner, at least in the sense in which political scientists tend to use this term: as a master heuristic that orients the ideologue politically, organizing most or all of her political ideas. However, at the risk of quibbling, I think Marietta dilutes the power of this analysis of Trumpian nationalism by describing it not only as an ideology, but also as a branch of conservatism, as a symbol, as an identity, and as a value. Let me say a few things about each.

Trump and Conservatism

Marietta’s conception of conservatism strikes me as too schematic. I know many conservatives who do not see society as fundamentally fragile and in need of social glue, and many who do not care about anything like “ordered liberty” or a golden mean between freedom and authority. Marietta’s description fits certain conservatives, such as Straussians, but they are a tiny band of intellectuals without any discernible popular influence. At the mass level, standard journalistic depictions of three main groups of conservatives—Tea Partiers (small government/constitutional conservatives), cultural conservatives, and foreign-policy conservatives—do not seem to be in need of updating, at least not yet.

What Trump’s surprising popularity does show, I think, is that nationalism unites many conservatives of all three types—along with many non-conservatives, too. The transcendent appeal of nationalism makes considerable intuitive sense, as nationalism is more elemental than the ideologies that attract well-educated and politically literate adherents. It’s so basic that small children can understand it. Indeed, no matter how little you know about politics, it is likely that you were indoctrinated with nationalism when you were a small child. Trump, indoctrinated in the same way, and having learned little else about government, policy, or history in the meantime, is the ideal exponent of the most simplistic possible political ideology: that of “America first.”

This ideology offers its adherents a key to understanding the otherwise-confusing world of politics, even if they lack much interest in or knowledge of it. The key is to ask oneself whether a politician intends to put the interests of “Americans” before those of “foreigners.” The question of whether the mere intent to help Americans will accomplish the objective (let alone the question of whether Americans deserve priority over non-Americans) goes unasked. This immensely simplifies what would otherwise be a complex world of public policy: the world of policy debate. In policy debate, what is at issue is usually whether a given proposal that sounds as if it will serve the interests of Americans (for example) will actually do so. The answer is rarely as straightforward as deep nationalists believe. But this is part of the appeal of deep nationalism, which has little to do, as far as I can tell, with conservatism.

Nationalism and Symbolism

Part of the way nationalism gets inculcated is through the apotheosis of symbols such as the American flag. These symbols acquire emotional resonance, and this emotional resonance may help to explain why people turn “naturally” to their nationality when they think about politics (especially insofar as they know relatively little about it). So a full analysis of the cognitive role of nationalism might very well need to explore the emotional power of nationalist symbols. Such an investigation would have to go beyond both hyper-rationalist (rational-choice- inspired) theories of political heuristics and the irrationalist, psychological understandings of politics that I’ve been trying to challenge in my ongoing series of essays, where I have pushed back against accounts of Trump voters as xenophobes and authoritarians.

For this very reason, however, it is important to spell out carefully how the emotional or a-rational appeal of nationalism is connected to its cognitive function. Until we succeed in doing that, I worry about the confusion that might be created if we use the language of “symbolism” to describe nationalism, since this language currently connotes the groundlessly emotional. My position is that nationalism is illogical, but that the lapse in logic is not apparent to people who have been indoctrinated with nationalist presuppositions. It would be unfair—uncharitable—to say that they are irrationally clinging to nationalism, in the sense that they somehow know it is wrong. But to say that nationalism is symbolic may suggest something similar: that nationalism is merely an empty screen onto which people project their irrational desires. I don’t think Marietta is saying that, but it’s a connotation of calling nationalism “symbolic” that I think it’s best to avoid.

Nationalism and Identity

The same worry colors my reaction to using the language of “identity” to describe nationalism. There’s no denying that nationality is probably the central “identity” of most people in the modern world—at least in the bare sense that, if asked “who they are,” they are likely to answer “an American,” “a Mexican,” etc. Yet, without doubting the existence of national identities (in people’s heads), I wonder how important “identities” are to people who have not been influenced by academic discussion, where identity politics has been extremely important for several decades.

National identity can be very important in helping people to organize their thoughts about politics. Yet thinking about politics isn’t all that important to most people. So we may mischaracterize the situation if we project onto such people an obsession with their national identity. Similarly, identity itself may not be important to most people. Non-intellectuals’ answer to the question of “who I am”—namely, that I am the person behind my eyeballs—may feel so unproblematic that the very question of identity is a non-issue for them. The language of “identity” may inappropriately import the preoccupations of academics into our understanding of mass politics.

Nationalism and Values

Unquestionably the ideology of nationalism takes certain values for granted, but I don’t see the sense in calling nationalism a value, as Marietta does. Nationalism—the ideology—is not itself valued by nationalists (except perhaps by those who derive so much meaning and purpose from it that they love it for its own sake—members of the alt-right, for example). Nor, at least in the American context, does it seem right to say that “the nation” is valued, as such, by nationalists. There is no tradition of extolling “the American nation” as if it were an end in itself. But that’s what I take a value to be: an end in itself.

Nationalism and Egalitarianism

Even more important than Liah Greenfeld’s distinction between civic and ethnic nationalism, cited by Marietta, may be her observation, in Nationalism: Five Roads to Modernity, that nationalism is inherently egalitarian—within the borders of a given nation-state. Thus, the end in itself that is presupposed by nationalism is the equal worth of the lives of one’s conationals. In this view, rather than being a value, nationalism is premised on a value: the equal worth of one’s fellow citizens. (The causality may run from the establishment of a nation-state to the presumption of equality among its citizens, but this is probably because the idea of nationality implicitly contains the presumption of equality.)

Since I share Greenfeld’s view, I resist Marietta’s suggestion that nationalism embodies a value that competes with egalitarianism. It seems to me that nationalism is a form of egalitarianism; and that it is, in fact, the form that egalitarianism almost always takes in the modern world.

However, nationalist egalitarianism is self-contradictory in limiting itself to equality among the human beings who happen to live within historically arbitrary national borders, while treating the lives of those outside those borders as if they have no worth. This is what makes nationalism illogical. Its tacit definition of who should be treated equally is arbitrary.

Wilkinson’s reply illustrates the illogic. So let me analyze his response before turning, in conclusion, to Marietta’s qualms about the psychological practicability of cosmopolitanism.

The Nationalist Scapegoat: Xenophobia

Wilkinson is an egalitarian and extols the egalitarianism that nationalism makes possible within the borders of a nation-state. Yet, according to nationalism, equality stops at those (arbitrary) borders. Viewed from outside of those borders, nationalism is inescapably inegalitarian.

Wilkinson is aware of this problem but does not really address it. Instead, he presses hard on the distinction between nationalism and xenophobia, with xenophobia taking the rap for inegalitarianism. But even if xenophobia did not exist, nationalism would remain inegalitarian from the perspective of those outside a given nation-state’s borders.

This isn’t just a philosophical issue. Non-xenophobic nationalism can easily justify the immigration restrictions that Wilkinson opposes, as well as the trade restrictions and the foreign-policy isolationism that Trump advocates (or used to advocate, before being enlightened about its adverse consequences by his generals). Such policies can be seen—indeed, are seen, every day, in the normal state of our political discourse—as serving the interests of our fellow citizens, not as punitive exercises directed at despised outsiders. This is the political discourse that I am trying to get us to examine critically. Insisting that Trump is set apart from this discourse, because instead of nationalism he appeals to xenophobia, inadvertently blocks an examination of the discourse itself. It entrenches the complacency with which nationalism—“good,” non-xenophobic nationalism—is typically viewed, because it contrasts this type of nationalism against its evil, xenophobic twin. Yet both types of nationalism can produce the same policies—the very ones Wilkinson opposes.

How Non-Xenophobic Nationalism Works

A nice example of how this works is suggested by Wilkinson’s odd paean to the GDP growth that could be unleashed by open borders. It almost reads as if Wilkinson thinks that open borders are justified by the contribution of migrant laborers to the stock of global wealth. (There’s gold in them thar migrants—trillions and trillions of dollars of it!) But what if migrants contributed little to GDP? What if they reduced it? By Rawlsian standards at least, their contribution to or subtraction from GDP does not matter. What matters is that migrants, frequently among the least advantaged people in the world, would be helped by open borders. I think Wilkinson means to say this, because he asserts that most of the GDP gains would go to the poor. It is that fact that matters, not the sheer fact that “trillion-dollar bills” are allegedly being left on the proverbial sidewalk by closed borders.

Why, then, do developed countries close their borders? Wilkinson points out that closed borders are “constantly re-affirmed” by the democratic polities of the West. But what exactly is the political dynamic of “liberal-democratic institutions” that accounts for this?

The answer, I believe, is nationalism, which is taken for granted in the politics of Western countries (and all other countries). From a nationalist perspective, the welfare of one’s conationals is what matters; the welfare of “foreigners” does not. To sustain the high wages of one’s conationals, then, closed borders, tariffs on manufactured goods, and trade wars are often thought to be justified—not because nationalists want to hurt workers or would-be workers in other c from nicholemhearn digest https://niskanencenter.org/blog/nationalism-ethnocentrism-redux/

0 notes

Text

(DIS)EMBODIED GEOGRAPHIES

Phenomenological, psychoanalytic and ‘inscriptive’ approaches

“the word ‘body’ and the thing of ‘the body’ itself tend to be treated as obvious and requiring no explanation”

in terms of linguistics - how we speak and casual conversation/slang/euphemisms....

“get your body in shape” - assuming that before obtaining a ‘body ideal’ you are out of shape or have no shape... “but what does it actually mean for a body to have no shape?”

...”the ambiguity of becoming ‘some body’ in terms of both corporeality and subjectivity”

Corporeal form, when used literally, means the physical existence of something. There's the idea of "you" as a self-aware entity or a soul that defines how you will behave and react, which nobody can see or touch directly; and then there's your corporeal form, which is to say your actual physical body.

Subjectivity: the quality of being based on or influenced by personal feelings, tastes, or opinions. "he is the first to acknowledge the subjectivity of memories" the quality of existing in someone's mind rather than the external world. "the subjectivity of human perception"

advertisers encourage us to “craft our corporeal selves in such a way as to command respect - self-respect and the respect of others”... through our outward identity... enabling consumers to “become ‘somebody’ rather than remaining a ‘no body’. the question about how anyone can have ‘no body’ in the first instance is not posed’

“we use out bodies for grounding personal identity in ourselves and recognising it in others. we use other bodies as points of reference in relating to other material things” - pile and thrift 1995

the body as.... a ‘terra incognita’ unknown or territory unexplored...

“by body I understand a concrete, material, animate organisation of flesh, organs, nerves, muscles and skeletal structure which are given a unity, cohesiveness and organisation only through their psychical and social inscription as the surface and raw materials of an integrated and cohesive totality... the body biomes a human body, a body which coincides with the ‘shape’ and space of a psyche, a body whose epidermic surface bounds a psychical unity, a body which thereby defines the limits of experience and subjectivity, in psychoanalytic terms through the intervention of the (m)other" Grosz 1992

“a focus on the pre discursive, phenomenological, live body is one of the dominant views of the body in contemporary social theory”

merleau-pontys “locates subjectivity not in consciousness or in the mind, but in the body.”

“another approach is to treat the body ‘as a site of cultural consumption’... a surface to be etched, inscribed and written on”

“the body is significant mainly in terms of the social systems or discourses that construct it...socio political structures construct particular kinds of bodies with specific needs and wants”

“bodies are considered to be primary objects of inscription - surfaces on which values, morality and social laws are inscribed. constructionist feminists tend to be concerned with the processes by which bodies are written upon, marked, scarred, transformed or constructed by various patriarchal and heterosexist institutional regimes”...”this approach argues that the body cannot be understood outside place”

Dualism as described by Grosz: “a continuous spectrum that has been divided into discrete self-contained elements which exist in opposition to each other... these terms are not only mutually exclusive but mutually exhaustive...it leaves no possibility of a term which is neither one nor the other, or which is both.”

-dualisms dictate how we understand ourselves and the surrounding world. large basis for identity-

within this dichotomous structure “one term has a positive status and an existence independent of the other; the other term is purely negatively defined, and has no contours of its own; its limiting boundaries are those which define the positive term”

the mind/body dualism is gendered... “the mind has traditionally been correlated with positive terms such as ‘reason, subject, consciousness, interiority, activty and masculinity’...the body on the other hand has been implicitly associated with negative terms such as ‘passion, object, non-consciousness, exteriority, passivity and femininity” Grosz

“the body is seen as reasons ‘underside’ it’s ‘negative, inverted double’...men are afforded the privilege of being able to ‘transcend’ their bodies. they are not ruled by their outer shells

“of course in reality both men and women ‘have bodies but the difference lies in that men are thought to be able to pursue and speak universal knowledge, unencumbered by the limitations of a body placed in a particular time and place whereas women are thought to be bound closely to the particular instincts rhythms and desires of their fleshly located bodies”

...”this supposed universality is what michele le does refers to as the exhaustiveness of masculinist claims to knowledge; it assumes that it is comprehensive and thus the only knowledge possible”

Men: they know-all, be-all

“although it is granted that man has a body it is merely as an object that he raps, penetrates, comprehends and ultimately transcends. As his companion and compliment, Wman is the body. She remains stuck in the primeval ooze of natures sticky immanence, a victim of the vagaries of her emotions, a creature who can't think straight as a consequence”

-...relates to other reading which alludes to visceral feelings and emotions as corporeal surfaces...therefore disconnected from the mind and intrinsically linked and inseparable to the women... therefore she cannot perform with rationality. -

-white men are able to ‘transcend’ their bodies, an opportunity not afford to women, blacks, homosexuals etc i.e. the ‘other’ ... another dualism... white man/everyone else what the body does....hormones and emotions etc affects judgement. men are not held back by these bodily functions, their exteriority, are able to rise above. whereas women and other minorities are judged through their exterior.-

‘the master subject’ “understands his supposed disembodied rationality to be the norm... embodied, irrational woman on the other hand, represents difference from the norm, the other”

“masculinist rationality is form of knowledge which assumes a knower who believes he can separate himself from his body, emotions, values, past experiences and so on... this allows for hi to consider his thoughts (his mind) to be autonomous, transcendent and objective; mess and matter free, so to speak”

‘the subject is conceived as a disembodied, rational, sexually indifferent subject - a mind unallocated in space, time or constitutive relations with others (a status normally only attributed to angels)

“Although we all have bodies only those people who conceptually occupy the place of the mind are ‘thought’ to be able to produce such knowledge. for those people who are constructed by Cartesian philosophy as being tied to their bodies, transcendent visions are not considered possible. their knowledge cannot count as knowledge for it is too intimately grounded in, and tainted by, their (essential) corporeality”

^^the other, therefore we ignore the needs of any but white males in geography - public space

“how cities make or create bodies with certain desires and capacities....surely there exists a mutually constitutive relationship between people and places”

“there is a ‘complex feedback relation’ between bodies and environments in which each produces the other... examining the ways in which bodies are ‘psychically, socially, sexually and discursively or representationally produced, and the ways, in turn, that bodies rein scribe and project themselves onto their sociocultural environment so that this environment both produces and reflects the form and interest of the body”

0 notes