#akamoji

Link

In case the link ever goes down, here is an archived version.

An article introducing styles falling under the Akamoji umbrella, which is also known as the overall genre name for Shibuya styles.

Includes the obvious, but the illustration is a bit dated:

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

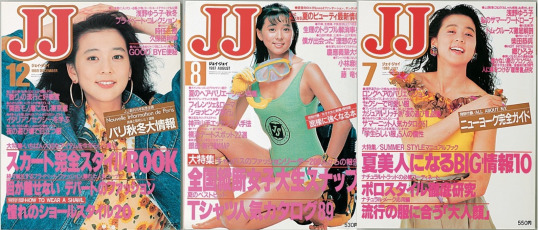

The Muses of 1980s JJ

JJ and the Rise of the Akamoji-kei

In the early 1980s, the most glitzy clubs, restaurants, and boutiques were taken over by "JJ girls," and JJ's influence was palpable.

During this period, the magazine shifted away from relying on haafu models and instead featured full-Japanese women as its primary models. This shift represented a move from exotic beauty to models who resembled the average reader more closely. Many of these models were also active college students attending prestigious institutions.

The first JJ muse of that period was 20-year-old Ryoko Takahashi, who replaced Marie Krabin as the cover model in 1981. Takahashi possessed a refined and classic look that seamlessly complemented the "newtra" fashion style heavily promoted by the magazine.

She got married and retired when she was still in her 20s. After a long hiatus, she returned in the mid-2000s to Kobunsha fashion titles targeted at women in their 40s and 50s. She now goes by the name Ryoko Tamai.

21-years-old Chikako Kaku took over as JJ's cover girl in 1982. That same year, she made her debut as an actress in an afternoon drama. From a traditional wealthy family, she graduated from the Joshibi University of Arts and Sciences Junior College.

Although her tenure as the primary model lasted only a year, Chikako made a return as a cover girl for three issues in 1985 and also appeared several other times to promote her acting projects. Remarkably, at the age of 60, she continues to be active in the entertainment industry, maintaining her roles as both an actress and a model.

Chieko Kuroda, known as Chieko Kashimoto at the time, stands out as perhaps the most prominent JJ model of the 1980s. While most models typically held the position of cover girl for about a year, she maintained her role for over two years.

Chieko made her debut in the magazine while still a student at Seijo Junior College. Initially, she was discovered by the editor in charge of the sports fashion section, and her appearances were primarily confined to the sports pages. However, readers quickly grew fond of her, and her presence in the magazine expanded. Ultimately, in 1983, she was appointed as JJ's cover girl. Her rise to prominence paralleled the ascent of the editor who had initially spotted her, and he eventually became the editor-in-chief.

At the age of 24, Chieko retired from modeling and pursued a conventional career. She got married at 28, and the following year, she welcomed her daughter into the world.

In 1995, a decade after her departure from modeling, Kobunsha decided to launch a groundbreaking fashion publication, the first one aimed at married women in their 30s. The former JJ editor-in-chief who had originally discovered her invited Chieko to lead this innovative project. She accepted the offer and came out of retirement. The magazine, VERY, achieved tremendous success, reestablishing Chieko as a fashion influencer for women in her age group.

As of 2022, she continues to be actively involved in the entertainment industry, working as a model, actress, and TV personality.

In 1985, Towako Kimijima, then known as Towako Yoshikawa, became the new "signboard model" for JJ.

Similar to her predecessors at JJ, Towako received her education in prestigious institutions. Her journey into the world of modeling began during her junior high school years, where she appeared in influential teen publications like MC Sister and Seventeen. At the age of 19, she was appointed as the star model for JJ. Towako concluded her tenure with the magazine in 1987, and the subsequent year marked her debut as an actress.

Following her JJ graduation, she had an eventful career marked by a lot of family drama.

In 1995, she publicly announced her marriage to dermatologist Akira Kimijima, who happened to be the son of the renowned fashion designer Ichiro Kimijima. Although initially planning to retire from the entertainment industry after their lavish wedding, their union instead opened the doors to a series of family dramas that drew intense media scrutiny. Akira, raised by his grandmother as an out-of-wedlock child, found himself entangled in conflicts with his siblings over their roles in the Ichiro fashion empire. Tragically, Ichiro Kimijima passed away from a heart attack in 1996, further intensifying the feud. Eventually, Akira assumed control of his father's empire, though it was laden with substantial debt.

Towako's personal charisma proved to be the savior of the family's fortunes. Her striking beauty and impeccable style allowed her to successfully establish herself as a leader in the beauty and fashion industry for women. Her cosmetics and skincare line enjoyed remarkable success, solidifying her position as an authoritative figure on aging gracefully and embracing girly, "conservative" fashion. What made Towako particularly groundbreaking was her ability to maintain popularity among women in their 20s, despite the ageist nature of Japanese society, while she herself was in her late 30s.

Now in her late 50s, Towako is a mother to two adult daughters. Her cosmetics and skincare line continues to thrive and is distributed through her husband's company.

Analyzing the history of JJ cover models reveals a significant cultural shift between the 1970s and the 1980s. Interestingly, every cover muse from the 1970s has long since retired from public life, with limited information available about their activities after leaving the magazine. During that era, the "shelf life" of a young model was quite brief, and societal expectations often pushed women to marry at a young age and leave their careers behind. Even Momoe Yamaguchi, a top idol and pop star of the 1970s, chose to retire at the height of her career in 1980 to fully dedicate herself to married life.

In stark contrast, nearly all of the 1980s stars who graced JJ's covers remain active in various fields. While a few, such as Reiko Tatami and Chieko Kuroda, briefly retired, both eventually returned to modeling once their children had grown up.

However, some of JJ's stars from the 1980s have chosen to maintain a degree of anonymity in their post-modeling lives. This is particularly true for Kae Miyadai, JJ's "super dokumo" from the early 1980s. Miyadai is the first and only "dokumo" to ever grace the magazine cover, which she did 3 times between 1987 and 1988. Since then, however, very little is known about her.

Risako Miura, formerly known as Risako Shitara, held the distinction of being the last JJ signboard model of the 1980s. Her modeling journey began in 1987, and she maintained her status as the magazine's top model until 1991, marking the longest tenure during that era. Interestingly, she appeared on the magazine's cover relatively few times, with just seven covers to her name. This was because her tenure coincided with a period when actresses and celebrities were prominently featured on the front covers.

Risako left a lasting impression on JJ's readership. Born in New York City and the daughter of a Mitsubishi director, she completed her education at Tamagawa University. In addition to her modeling career, she ventured into acting in the early '90s. In 1993, she married the renowned soccer star Kazuyoshi Miura in a lavish ceremony attended by numerous celebrities.

Following her marriage, Risako devoted herself to family life for a few years. However, in 2000, she stepped into the role of the main star for VERY Magazine, succeeding Chieko Kuroda, and continued in this capacity for six years. Since then, she has occasionally returned to modeling and remains active on social media platforms..

Mariko Ishihara played a pivotal role in the evolving landscape of JJ magazine when actresses and young celebrities began dominating the magazine's covers. During the period spanning 1986 to 1987, she held the distinction of being the magazine's primary muse, gracing its cover on six separate occasions.

Ishihara's most distinctive feature was her thick eyebrows. In the late '70s, Brooke Shields, known for her appearances in commercials for cosmetic company Kanebo and others, gained immense popularity in Japan. Her signature unruly brows were an integral part of her appeal. Mariko Ishihara demonstrated that this striking look could also work on Japanese women, significantly influencing beauty standards of the era.

She is also widely remembered by her role in the TV drama "Fuzuroi no Ringotachi," which revolved around a group of college students navigating the complexities of love. As an actress, Ishihara projected an image of innocence combined with a wild and unpredictable streak. Over time, her untamed personality began to overshadow her acting career, and in recent decades, she has become more recognized for her involvement in media scandals. Nonetheless, her legacy as a fashion and beauty icon from her past remains indelible.

In the summer of 1988, Fuji TV aired a drama called "Dakishimetai." The show style gained the moniker of "trendy drama" because everything in it was very trendy: the settings, the actors, and the outfits. It really captured the glamour of the bubble years of Japan. And it was a success, especially among young women, turning the show's lead actresses -- Yuko Asano and Atsuko Asano (who, despite the same last name, are not related) -- into the most prominent fashion influencers in the country.

Fueled by the "W Asano" boom, Atsuko and Yuko became cover girls of all akamoji titles between 1988 and 1990. And JJ was no exception. Atsuko graced JJ's cover 5 times, while Yuko (center) amassed 4 front covers, giving "W Asano" a total of 9 covers between 1989 and 1990.

Honami Suzuki is the actress with the most JJ covers, gracing the front of the magazine on a remarkable 10 occasions spanning from 1987 to 1992.

Her first appearance was in the June 1987 issue, shortly after she debuted as an actress. Throughout her ascent, she kept being featured in the magazine. Honami finally reached mega-stardom in 1991 when she starred in "Tokyo Love Story," one of the most popular TV dramas of all time. At the peak of her popularity, she retributed the magazine support during her ascent, appearing 3 times on the cover. Her last appearance was in the October 1992 issue.

In the subsequent year, JJ departed from featuring celebrities and returned to showcasing their signboard models as cover girls starting from 1993.

#jj#1980s#magazines#akamoji-kei#akamoji#w asano#yuko asano#atsuko asano#honami suzuki#marie ishihara#risako miura#towako kimijima#chieko kuroda#chikako kaku#mariko ishihara

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jfashion News Update:

Hello Everyone!

For anyone who is/was a fan of gyaru fashion: it was announced yesterday that the parent company of several gyaru brands (Cecil Mcbee, Ank rouge) will be shutting down several of its brands!

As of right now, Cecil Mcbee and Be Radience (an otona Kawaii/ Akamoji kei brand), and a few others are set to shut down.

Ank Rouge, Deicy ( I think Deicy use to be a gyaru brand? But they changed styles and I can’t really define their style now...), and two other stores will remain in business. I would assume though that if they start to not do good they are at risk of shutting down in the future as well?

I have mixed feelings about Ank Rouge, but with Lizlisa not doing so hot as well, if Ank Rouge were to ever close I feel like Himekaji would truly be dead. (Though at this point I think Himekaji is only really popular overseas? Not so much in Japan anymore?)

#japanese fashion#jfashion#gyaru#gyaru fashion#gyaru kei#himekaji#larme kei#cecil mcbee#kawaii fashion#ank rouge

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Continuando con la campaña Conan Love Project (CLP) que promociona la próxima película “Karakurenai no Love Letter”, el próximo número de la revista CanCam #5 2017 incluirá de regalo un Registro de Casamiento. El diseño del mismo, incluye la ilustración del tomo 26 donde aparece la obra de teatro con Ran como la Princesa y Shinichi como el Black Knight.

CanCam es una revista de moda japonesa orientada a mujeres de entre 18 y 25 años. Su nombre es la abreviatura de “I Can Campus” ya que apunta a un público de chicas universitarias que trabajan y, además, encuentran el espacio de juntarse con sus amigas o su novio luego de la jornada laboral. El público, similar al de la revista Nonno, son chicas independientes. Estas razones hacen que, además de ser de la misma editorial de Shonen Sunday, personajes como Haibara Ai la elijan.

El formato de la revista es similar a un catálogo y los estilos de moda japonesa en que se la clasifica se llaman “akamoji kei” (el de las letras rojas), “mote kei” y “otona kawaii”.

#detective conan#dcmk#dcmk news#detective conan movie#Karakurenai no Love Letter#cancam#Black Knight#shinichi kudo#ran mouri#haibara ai#otona kawaii#akamoji kei#mote kei#jfashion#japanese fashion#japanese fashion magazine

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any thoughts on bis so far?

Hi!I have not yet received my copy of the magazine yet, however from the content on the website, here’s my opinion so far.

In terms of aesthetics, I think bis will be a very beautiful looking magazine. From the colour scheme to the logo to the images they’ve teased so far, it looks very pretty, soft and vintage-looking. Just from the pictures shown pre-launch, like on the Instagram feed, I have high expectations for beautiful dreamy looking editorials. From the contents teaser page, the editorials look like they will be nice, so I look forward to them.

Aesthetics aside, in terms of the content I’ve seen so far, I was slightly taken aback by it. The first article I read was, 「NG Fashion 10」. It is about 10 types of ‘boyish’ fashions that boys do not like girls to wear. It is like something from Japanese Seventeen Magazine (which it reminded me of because I read this kind of article in it when I was younger). I found that with a concept aimed at women in their 20s, it comes off as very teen-magazine. However there a lots of different topics including study and travel which seem interesting and more mature.

bis looks like it will fundamentally be an akamoji magazine. Which is expected, but I did not expect it to as akamoji as it is. Actually, one thing it made me think, is how unique LARME is. The fashion, beauty and focus on girliness is akamoji, but it also has an aomoji outlook. It is individual and the aim is to look as girly etc as you’d like because you like it. (But I don’t think LARME is void of this kind of content either (see Issue 021 - I was surprised in the same way when I first saw the feature on 100 ways to get praised by your boyfriend)). I don’t particularly hate this kind of typical akamoji content, but it’s not to my interests and from my point of view it’s quite balanced out in LARME.

I’m sure everyone’s opinion differs; perhaps this kind of content will not be an issue with others.

Anyways, it’s still early days, the magazine may be different to the website, and the magazine may change it’s tune through time. The magazine will launch it’s first issue in September so the actual magazine may be a little different to the pre-issue. Also through the questionnaire, they can adapt to the readers’ views so far.

This is a long opinion which does not even regard the physical magazine, and I refer back to LARME as comparison a lot (even though I know and cannot expect that they are going to be the same type of magazine) so my opinion so far may not be so useful to read.

But when I get my copy I will write a review of my impression and I will be able to talk more about the aesthetic fashion side of things which I’m excited for. Thank you for asking!

1 note

·

View note

Photo

chibi’s for 1Greengrass1′s contest @ Da by me some time ago

0 notes

Photo

01/02/04 (color edited)

Blouse, dress and shoes : Axes femme

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

In case the link ever goes down, here is an archived version.

Some people might not be aware, but Girly Kei is one of the very few fashions that is both a Akamoji (Shibuya) and Aomoji (Harajuku) style and therefore featured in both of Mynavi's articles.

As usual, dated illustrations.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

JJ and the Rise of the Akamoji-kei

The “new traditional” Kobe-born style was first identified by AnAn. But it was JJ that transformed it into one of the most popular trends of the 1970s.

“Newtra” was promoted by JJ for years and evolved through time. But, in the beginning, fitted shirts and pleated skirts were a must. High-impact prints in the shirt were encouraged for those who wanted to spice things up.

Loafers with 3 to 5-cm heels were the footwear of choice.

As for the bags: short straps, elaborate clasps, and, as with the shoes, metal details.

“Newtra” was a formal look, but JJ recommended metal accessories and scarves to make it more playful. A touch of elegance could be added with accessories, shoes, and purses by high-end brands such as Celine, Gucci, and Christian Dior.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Muses of 1970s JJ

JJ and the Rise of the Akamoji-kei

From 1976 to the beginning of 1978, haafu (mixed-race) model Theresa was JJ's main cover star. Retired since the early 1980s, there's little to no information about her on the internet.

Actress Masako Natsume (right), Naomi Hagi (center), and Naho Satomi (left) were the first JJ full-Japanese cover girl. They appeared in the August 1978, April 1979, and May 1979 issues.

Masako was one of the most beloved actresses of the 70s and early 80s. She tragically passed away due to leukemia in 1985, when she was only 27 years old.

Born Masako Odate, she made her debut in 1975 and had a string of memorable roles. She starred in the international hit "Saiyuuki and in several successful movies. From a traditional wealthy family, her mother opposed her career as an actress and asked her not to use her real family name.

At the time of the JJ cover, she was starring in the Japanese cosmetics manufacturer Kanebo's highly-popular "Kooky Face" campaign. The summery commercials, where she appeared topless, were so popular she adopted "Natsume" (Summer) as her artistic last name.

Naomi Hagi and Naho Satomi (now known as Sayaka Tsuruta) were also famous actresses of that period..

After testing the waters with actresses, JJ appointed Miyuki Takahara as its first full-Japanese cover model in the middle of 1978. At the time, Miyuki was enjoying great popularity as the face of the cosmetic company Shiseido. Despite being retired for decades, her Shiseido commercial is still fondly remembered.

Between 1979 and 1980, JJ again had a mixed-race model as its muse: Hawaii-born fresh-faced beauty Marie Krabin. Much like the other models from the 1970s, she has since retired from the industry, and there is scarce information available about her online, despite her significant popularity during her heyday.

1 note

·

View note

Text

JJ and the Rise of the Akamoji-kei

"Hamatra" (from "Yokohama Traditional") was a style inspired by the students at Yokohama's Ferris Women's University. It spread all over the country after being popularized in the pages of JJ around 1979.

The "Hamatra" look included polo shirts, tartan skirts, logo sweaters from Berkley, select shop Ships, and Boathouse and loafers.

But the three sacred "Hamatra" items were pieces from boutiques in the Motomachi shopping district in Yokohama: Mihama shoes, a Fukuzo shirt, and a Kitama handbag.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

JJ and the Rise of the Akamoji-kei

The June 1975 launch issue of JJ magazine. Haafu model Keren Yoshikawa was the first covergirl.

JJ is the first akamoji-kei magazine. Akamoji-kei means “red-letter system,” and it’s a reference to the logo of these magazines, which used to be red.

The first edition already promotes one of the trademarks of JJ styles, “newtra” (“new traditional”). It promises street snaps of “newtra” girls in Kobe, Yokohama, Tokyo, and Osaka, as well as a guide to fashionable boutiques in these towns. Riding the “Anon-zoku” wave, the cover also prominently announces a touristic article on the city of Okayama, focusing on the local temple.

.

1 note

·

View note

Text

JJ and the Rise of the Akamoji-kei

In the early 1980s, Japanese media was overtaken by college girls. Five years before, a magazine paved the way for their dominance, forever changing the fashion and the publishing industry.

Red-colored letters ushered in a revolution in the Japanese fashion scene. While this may sound a bit odd, "akamoji-kei" ("red-letter system") is the name of a segment of magazines that were, historically, the most mainstream in Japanese fashion: JJ, CanCam, ViVi, and Ray. All four had their names on the cover in big red letters, hence the classification. They featured fashion styles palatable to the mainstream taste but with touches that would make readers stand out, seem more affluent and ideally help them bag a wealthy husband. These upscale touches helped them differentiate themselves from readers of market leader Non-no, which had a more simple mission of simply teaching Japanese girls how to look cute.

The "akamoji" publication boom started in 1975 and, throughout the 1980s, revolutionized the fashion and the publishing industry. Like the broader Japanese publishing sector, it has faced a decline for over a decade. However, its influence undeniably played a pivotal role in shaping Japanese oshare culture, leaving a lasting impact that endures today

JJ magazine stood as the pioneering akamoji figure. Throughout its history, it remained one of the most influential titles in Japanese fashion. Ironically, it also became the first casualty in the akamoji field. Nevertheless, its impressive legacy lives on.

Oshare ‘70s

In 1970, Japanese fashion underwent a transformative shift with the debut of Japan's first female fashion magazine, AnAn, published by Heibon Shuppan. Beyond merely conveying the latest trends, AnAn was the trigger for an era of trend-conscious consumerism centered around visually captivating magazines—magazines to view, not only to read.

AnAn presented a world brimming with dreams, featuring beautiful foreign models, high-fashion attire, and lifestyle advice on how to lead a chic and fashionable life. It became the first magazine to validate the concept of "girls' culture," which emphasized that being a young woman encompassed more than just traditional roles like child-rearing and marriage. It was also shopping for stylish clothing, aspiring to explore the world, and embracing a trendy (oshare) lifestyle.

A year later, Shueisha's Non-no emerged with similar principles. However, it brought the dream world closer to reality by promoting more attainable, easy-to-emulate fashion. Japanese women, eager for clear fashion guidance, embraced this approach, propelling Non-no to overtake AnAn as the market leader.

By 1975, with two successful and influential fashion magazines dominating the market, the viability of this publishing field was firmly established. Another editorial house, Kobunsha, also wanted to try its luck at it. And so, JJ was born.

Until then, nearly every fashion magazine had its roots in a weekly publication. AnAn, for instance, stemmed from the editorial team of the influential men's weekly Heibon Punch. The main competitor for Heibon Punch was Shueisha's Weekly Playboy, whose editors, after the success of An-An, decided to launch Non-no.

With JJ, it was no different. It launched as a spin-off of the women's weekly Josei Jishin, the title that, a decade earlier, had popularized the term "office lady." "JJ" is an abbreviation of its parent magazine name.

However, beyond its parent magazine's influence, JJ charted a different course. While most weeklies, including Josei Jishin, focused on current affairs and gossip and were printed in black and white newspaper style, JJ followed the fashion magazine paradigm. It placed a strong emphasis on style, featured abundant visual content, and primarily utilized full-color printing. In doing so, JJ adhered to the established precedents while simultaneously breaking some traditional publishing norms.

Japanese Faces

In '70s Japan, fashion and affluence aspirations were tightly linked to foreign glamour. This is why AnAn and Non-no often used white, blonde, and blue-eyed models on their covers and editorials. But when the initial issue of JJ hit the stands, the cover featured Keren Yoshikawa, a haafu (mixed-race) model, bridging the gap between West and East glamour.

While haafu models were not uncommon in fashion magazines, JJ took a more distinctive approach by rarely featuring white models. This strategic decision proved immensely successful and set a new industry standard. By 1981, both Non-no and AnAn had followed suit, featuring exclusively Japanese models on their covers.

However, what initially set JJ apart was its emphasis on college students' fashion. Female students from prestigious institutions took center stage in its features and articles, showcasing their styles, preferences, and lifestyles. At that time, higher education was not as accessible to most women, and those who did attend university often hailed from affluent or traditional backgrounds. Consequently, the fashion of female campus students came to represent the style of young women from well-to-do families with conventional values. It was this particular style, along with all its associated connotations, that JJ and subsequent akamoji publications popularized on a grand scale.

From Elite Campuses to the Mainstream

In her book "JJとその時代" (JJ to sono jidai), Suzumi Suzuki contends that before the 1970s, women's magazines primarily catered to established groups like housewives and schoolgirls. In contrast, magazines like AnAn and subsequent fashion publications played a distinct role: they pioneered the creation of new societal niches.

The editors faced the challenge of identifying the collective desires and preferences of a hitherto undiscovered group of women and then giving these aspirations and consumption preferences a tangible form within the pages of a magazine. This process allowed the magazine to not only serve this emerging niche but also to amplify its influence within society.

Before AnAn and Non-no, women were already transitioning from dressmaking to ready-to-wear fashion. However, both publications captured the perfect moment to take advantage of this trend. It wasn't AnAn and Non-no that single-handedly created the impetus for women to travel solo domestically. However, these magazines, alongside Dentsu’s successful “DISCOVERY JAPAN” campaign, made it mainstream, creating the AnNon-zoku phenomenon.

Similarly, JJ tapped into the fashion styles prevalent among young women from affluent backgrounds, particularly in elite campuses across Japan, notably in Tokyo and the port cities of Kobe and Yokohama. The magazine expertly organized these trends in an easily digestible format and successfully marketed this affluent lifestyle to girls throughout Japan. In this way, a new style group emerged—the "JJ girl."

The "JJ Girl"

The term "JJ Girl" gained popularity in the early 1980s, referring to young women who regarded JJ as their ultimate fashion bible. These girls were typically associated with affluent, traditional backgrounds. They embraced a conservative style adorned with clothing and accessories from trendy domestic boutiques and high-end European brands. They attended elite institutions such as Konan Women's University, Keio University, and Aoyama Gakuin, while their residences were primarily in urban hubs like Tokyo, Yokohama, Osaka, and Kobe. They partied in the fashionable discos that took over Tokyo's glitzy neighborhoods during the 1980s, like Xanadu in Roppongi.

Naturally, JJ was a mainstream magazine with a sizable readership. Therefore, most of its readers did not hail from wealthy families or attend exclusive schools. In fact, when JJ first launched, just over 10% of women attended four-year colleges.

However, the underlying concept was that by adhering to the right fashion trends, any reader could aspire to become a "JJ girl" herself and, to some extent, live the glamorous lifestyle depicted in the magazine's pages. By playing their cards right, some might even achieve the ultimate prize: marrying a wealthy, stylish husband.

This last aspect was not secondary; it was, in fact, groundbreaking. While AnAn and Non-no mainly focused on girls enjoying fashion and "girls' culture" for themselves, JJ added a significant new layer. It utilized stylish fashion and engaging girls' hobbies not just to embrace an oshare lifestyle but also to attract the right kind of partner.

Thanks to this inviting narrative, JJ achieved considerable success in the publishing world, paving the way for a new wave of "akamoji" magazines that promoted similar trends in fashion and lifestyle. In 1982, the major publishing house Shogakukan introduced CanCam. The following year, Kodansha launched ViVi, and in 1988, Shufunotomo also entered the "akamoji" trend with Ray. However, as the pioneer, JJ maintained its status as the fashion leader and the most influential title within the akamoji realm throughout the ensuing decades.

The New Traditional for JJ Girl

JJ played a pivotal role in shaping some of the most significant fashion trends among young women from the 1970s to the early 2000s. It championed a distinctive style known as "ニュートラ" or "newtra" (derived from "new traditional"), which originated in the port city of Kobe in the Kansai region.

The "traditional" fashion movement had its roots in the mid-1960s when Japanese men embraced a style inspired by Anglo-American traditional looks and heritage brands. It evolved from Ivy fashion, one of the early influences on contemporary domestic fashion.

While men initially drove the "trad" trend, women brought fresh interpretations to it. AnAn magazine was the first to coin the term "newtra" to describe the fashion style favored by Kobe's young women and found in trendy local boutiques. Recognizing its popularity among affluent university students, JJ adopted "newtra" as its signature style from its inception, spreading its influence nationwide.

The "newtra" style, in line with the early akamoji fashion ethos, leaned towards a "conservative" aesthetic, which meant avoiding denim and other casual attire. Over the years, the "newtra" style underwent various transformations, but its classic form typically featured a well-fitted shirt, a knee-length skirt, and heeled loafers (link).

The shirt could be simple white or a "high-impact" piece adorned with extravagant patterns. Pleated skirts were preferred, though formal pants were also acceptable. When it came to loafers, they sported heels ranging from 3 to 5 centimeters, with metallic details being a must. Metallic accents were not limited to shoes but extended to bags and accessories. This look had a touch of formality, yet girls could infuse playfulness into it through the use of metallic accessories, printed shirts, and scarves. The use of high-end European brands such as Christian Dior, Gucci, Hermes, and Celine was highly encouraged, especially for the shoes, bags, and scarves.

The fact the style originated in Kobe isn't coincidental. As mentioned before, the Western imaginary conveyed affluence and style, and the port city of Kobe is considered one of the most cosmopolitan cities in Japan. When Japan's policy of seclusion ended in 1853, Kobe was among the first cities to engage in trade with the West. Many Western companies established headquarters there, and Western architectural influences are prevalent in Hyogo Prefecture. Kobe boasts a substantial elite population with a reputation for sophisticated cosmopolitan tastes. As a result, this capital of Hyogo Prefecture became a favored destination for fashion publications seeking to track trends and discover stylish young women.

Kobe encapsulated several of JJ's core values, making it an incredibly influential city for the magazine. "Newtra" was just one of the numerous Kobe-born fashion trends that JJ would propel into the mainstream fashion culture of Japan as a whole.

The "Hamatra" Craze

Having popularized "Newtra," JJ set its sights on another port city, Yokohama, in search of the following fashion sensation. In 1979, the magazine introduced "Hamatra," a contraction of "Yokohama Traditional." (link)

Yokohama, Japan's second-largest city and the capital of Kanagawa Prefecture, is just a short train ride from Tokyo. The "Hamatra" style emerged from students at the local Ferris Women's University. A distinct feature is the origin of their clothing—a variety of local boutiques nestled in the Motomachi commercial district. Key items in this trend included polo shirts and sweaters from Fukuzo, Kitamura bags, and Mihama shoes.

While Fukuzo boutique clothing was not budget-friendly, it boasted high quality, in-house manufacturing, and a heritage that transcended generations. These attributes were highly esteemed in the pages of JJ, which often emphasized how young women from affluent backgrounds inherited their parents' appreciation for such brands. Kitamura and Mihama shared these same characteristics of tradition, quality, and Yokohama heritage.

Though these Yokohama-sourced pieces were often referred to as the "three sacred items," a plethora of other clothing and accessories flew off the shelves nationwide during this trend. Memorable additions included logo sweatshirts from Boat House and Tokyo's select shop Ships, as well as the bento-shaped bag from the French luxury brand Courrèges.

JJ featured a diverse array of styles on its pages, not limited to reiterations of the "traditional" style. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, "surfer" fashion surged as the prevailing youth trend. Interestingly, most of these young enthusiasts didn't actually surf, but it didn't matter. Unlike many Western cultures, Japan doesn't attach a profound meaning to fashion trends; sometimes, they border on "cosplay." During this era, Shibuya was brimming with boutiques catering to the surfer style, and "surfer discos" became all the rage. For "JJ girls," the surfer fashion meant donning rainbow-colored pieces, wide-leg jeans, tropical patterns and motifs, embroidered shirts, and accessories that exuded an "ethnic" flair. The ideal haircut was full of layers, mimicking the Californian glamour of Farrah Fawcett, preferably done at the trendy Claude Monet salon in Shibuya.

From the late 1970s to the early 2000s, JJ led the way for style-conscious university students and young office professionals. Post-high school, young women sought guidance on how to dress now that they were no longer bound by school uniforms. They aspired to fit in while standing out, projecting an image of affluence and trendiness beyond the "average" girl. They wanted to dress in a way that would catch the eye of the right individuals and impress prospective suitors and employers. JJ magazine effectively convinced them that it held the answers to turn these dreams into reality.

Dokumos and Cover Girls

JJ did more than just set fashion trends for university students across the nation; it led the way for college girls to completely take over the media. By 1983, they were a ubiquitous presence in commercials, TV shows, radio stations, and men's magazines, with an increasing number of fashion publications targeting them. College girls had become a national obsession.

But JJ was not concerned with the broader society. While college girls took over the general media, the publication remained laser-focused on one thing: influencing the taste of females in their late teens and twenties. The rest of the public was none of their business. So, there wasn't really any need to deviate from its usual route to cash in with the latest craze it helped create. Therefore, the title's stars did not change.

Firstly, there were the everyday college girls, the linchpin of the magazine's success. Though they were hardly ordinary, impeccably dressed, and attending prestigious institutions, they weren't larger-than-life celebrities. They felt relatable and authentic, which resonated with readers.

Despite the reliance on these ordinary students, the word dokusha moderu (see "Glossary") did not exist for most of JJ magazine's first decade. The origin of the term is unclear, but a few sources point to Olive magazine, which, around 1984, turned some of its high school readers into successful cover models.

Regardless of whether they coined the term or not, Olive spearheaded a "super dokumo" boom, and JJ was not immune to it. They appointed Kie Miyadai to this role. Miyadai became the first and only "dokumo" to grace JJ's cover, accomplishing this feat three times between 1987 and 1988.

While ordinary girls played a substantial role, JJ had professional models as their ultimate muses and cover stars. JJ's models functioned much like modern influencers; they were more than just beautiful faces and bodies. They embodied the magazine, lived their lives in accordance with JJ's philosophy, and shared insights into their style, purchases, and lifestyles on its pages.

The first JJ cover had American-Japanese Keren Yoshikawa, but right after, another haafu model, Theresa, took over the cover girl role. The first full Japanese woman featured on the cover was actress Masako Natsume in the August 1976 issue. At the time, Natsume was enjoying high popularity thanks to a summery, sexy campaign she was starring in for cosmetics manufacturer Kanebo.

Another Kanebo spokesperson, actress Naomi Hagi, adorned the cover of the April 1977 issue. In 1978, when JJ transitioned to a monthly publication, Miyuki Takehara became the first full Japanese model to take on the role of the primary cover girl for the magazine. At the time, Takehara was one of the nation's top models and the face of Shiseido. She was succeeded in 1979 by Hawaii-born Marie Krabin.

JJ saw significant growth during the 1970s, reaching its peak circulation in the mid to late '90s. However, its influence arguably peaked during the '80s, when "JJ girls" were the talk of the town.

At the beginning of the '80s, Ryoko Takahashi and Chikako Kako served as JJ muses and cover girls. Japanese college girls (and boys) were divided into two camps—those who admired (or lusted after) Ryoko and those who preferred Chikako's style. By 1983, the magazine's star had shifted to Chieko Kuroda, who became immensely popular, gracing the cover as the sole star for over two years. In 1985, Towako Kimijima took the spotlight, followed by Risako Miura (then Risako Chitara) around 1988.

Beyond their good looks and style, these women epitomized the magazine's ethos, hailing from "respectable" families and attending exclusive schools. For example, Rikako was the daughter of a Mitsubishi director.

During the first half of the '80s, JJ operated within its own realm when it came to famous personalities, seemingly unaffected by trendy names from the outside world. While popular idols, actors, and actresses occasionally made appearances in secondary sections or advertisements, they were conspicuously absent from the main pages. This contrasted with its primary competitor, CanCam, which often featured the era's top idol, Seiko Matsuda, on its cover and even provided her with an exclusive serialization in the magazine.

However, beginning with the May 1986 issue, JJ decided to adapt, and young female celebrities started to alternate with models as standard cover girls. Actress Mariko Ishihara, who was known for her distinctive bushy eyebrows that significantly influenced beauty standards of the time (alongside Brooke Shields, who was also immensely popular in Japan during this period), marked the inception of this new era.

While CanCam concentrated more on multi-talented idols, JJ primarily showcased actresses. Among the recurring faces were Honami Suzuki, Atsuko Asano, Narumi Yasuda, and Yuko Asano. Chikako Kaku, who had previously been a JJ model but had transitioned into an acting career, also made a return for three covers. Nevertheless, pop singers and idols did occasionally grace the cover. The legendary Seiko Matsuda starred in the October 1988 issue, while Asami Kobayashi featured on the front cover of the November 1987 and January 1989 editions.

The celebrity era did not last indefinitely. By 1993, models made a triumphant return, marking a new phase for the publication.

The rise and fall

As the 1980s drew to a close, Japan was experiencing an economic miracle. Money flowed freely, people indulged in various luxuries, and the fashion industry flourished, becoming a billion-dollar enterprise.

In the midst of this prosperity, JJ remained steadfast as the most influential publication among one of the most valuable consumer demographics: young women. The future appeared exceptionally promising.

However, the economic bubble eventually burst, ushering in an inevitable recession and marking the end of the dream years. For JJ, not everything was gloom and doom: during the tumultuous 1990s, it achieved its highest sales. Nevertheless, in the mid-2000s, a momentous event occurred—it lost its coveted top position among akamoji titles to a rival.

This transition marked a significant moment for a publication that had long been defined by its seemingly unshakable number-one status. Suddenly, JJ found itself in need of a new purpose, signaling the beginning of its decline.

JJ's First Issue

The Newtra Trend

The Hamatra Trend

The Muses of 1970s JJ

The Muses of 1980s JJ

Next: JJ's victorious 90s, its turbulent 2000s, and the end of an era.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Japanese Fashion Chronicles

1. An Intro

2. The Digital Fashion Takeover

3. Japanese Fashion and Society Glossary

From the Post-War to the ‘80s

4. Post-War Japan and the "Dressmaking" Craze

5. How Ivy Fashion Shaped Oshare Culture

6. A Visual Experience (Part 1)

7. A Visual Experience (Part 2)

8. The Tie That Binds

9. The Models That Started It All

10. How US Counterculture Changed Japanese Fashion (Part 1)

11. How US Counterculture Changed Japanese Fashion (Part 2)

12. College Girls' Domination

13. JJ and the Rise of the Akamoji-kei

14. Popeye's Revolution (Part 1)

15. Popeye's Revolution (Part 2)

16. ′70s Japan Trend Through the Music Charts (Part 1)

17. ′70s Japan Trend Through the Music Charts (Part 2)

18. ′70s Japan Trends Through the Music Charts (Part 3)

19. ′70s Japan Trend Through the Music Charts (Part 4)

20. ‘70s Harajuku (Part 1)

21. ‘70s Harajuku (Part 2)

22. Shoujo Manga’s Golden Decade (Part 1)

23. Shoujo Manga’s Golden Decade (Part 2)

24. Shoujo Manga’s Golden Decade (Part 3)

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

College Girls' Domination

During the early 1980s, Japanese media developed an intense fascination with college girls. However, what lay beneath this phenomenon?

Starting in 1980, college girls captured the nation's attention, serving as fashion icons for women and objects of desire for men. The media played a significant role in amplifying this craze, placing these young women in the spotlight.

A moment often credited with igniting this phenomenon was a television commercial by the camera manufacturer Minolta. The ad featured 21-year-old Yoshiko Miyazaki shyly taking off her jeans and T-shirts underneath a tree, revealing her full-figured bikini body. Japan was captivated by her curves and the fact that she was an ordinary student at Kumamoto University. Before this, many had perceived female college students as distant, intellectually gifted beings or hailing from privileged backgrounds. Thanks in part to Miyazaki's charisma, this image underwent a transformation: these women were not only bright but also approachable and beautiful.

Even before the Minolta commercial, the general media had begun to capitalize on the sexual allure of college women. In 1980, Weekly Asahi, a magazine targeting salarymen, started featuring attractive ordinary university students on its cover. A few months before the Minolta commercial, Miyazaki herself graced the magazine cover.

In 1981, the influential Nippon Cultural Broadcasting radio station launched the "Miss DJ Request Parade," hosted by a rotating panel of female students. It quickly gained popularity, and several of the featured women would follow in Miyazaki's footsteps, becoming famous TV personalities. Among them were Mari Chikura from Seijo University, Naomi Kawashima from Aoyama Gakuin University, and Keiko Saito, a junior of Miyazaki at Kumamoto University.

The "university students" boom would peak in 1983 when college girls became a prominent part of the raunchy late-night show "All Night Fuji." "All Night," which aired until 1991, would become one of the most influential shows of the decade.

Driving this frenzy was that an unprecedented number of women—1 in 3 high school graduates in 1983—were pursuing higher education, and public perception of this group was evolving to match the changing times.

However, the catalyst for all of this was a magazine called JJ, published by Kobunsha, which would go on to become one of the most influential fashion publications in Japanese history, solidifying college girls as influential fashion trendsetters in the country.

Next: JJ and the Rise of the Akamoji-kei

2 notes

·

View notes