#also I studied literature so I get hung up on singular words and the fact that Tuvok says 'we must accept' with Kes

Text

Coda. You of all people. Grief.

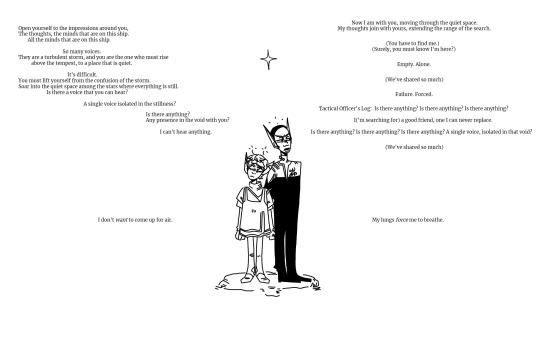

The way Kes had to break Tuvok's hold on her &

The way he kept asking if she heard anything - anything at all.

Open yourself to the impressions around you,

The thoughts, the minds that are on this ship.

All the minds that are on this ship. So many voices.

They are a turbulent storm, and you are the one who must rise

above the tempest, to a place that is quiet. It's difficult.

You must lift yourself from the confusion of the storm.

Soar into the quiet space among the stars where everything is still.

Is there a voice that you can hear?

A single voice isolated in the stillness?

Is there anything?

Any presence in the void with you?

I can't hear anything.

Now I am with you, moving through the quiet space.

My thoughts join with yours, extending the range of the search.

(You have to find me.)

(Surely, you must know I'm here?)

Empty. Alone.

(We've shared so much.)

Failure. Forced.

Tactical Officer's Log:

Is there anything?

Is there anything?

Is there anything?

I('m searching for) a good friend, one I can never replace.

Is there anything? Is there anything? Is there anything?

A single voice, isolated in that void?

(we've shared so much.)

I don't want to come up for air.

My lungs force me to breathe.

Patreon | Ko-fi

#Kes#Tuvok#st voyager#voy#st voyager coda#bea art tag#how is Tuvok roasted for his poetry in the same ep he says all this?#the way Kes gave up like 'I don't think this is working' before Tuvok did - the way she seemed almost...agitated? Not angry but like he was#pushing her - Chakotay had the crying & screaming scene and this was that scene for Tuvok#the way Tuvok calls her his friend when one of them is about to die#the way Janeway's like 'Tuvok - surely YOU can find me?'#-hand around the writer's collective necks- the way she alludes to all they've shared. And Yet. How RARELY we hear about this All.#Anyway this scene just struck a cord <3#transcript under the cut#also I studied literature so I get hung up on singular words and the fact that Tuvok says 'we must accept' with Kes#but 'I'm forced to conclude' when alone - he was REALLY trying and you can SEE that#waaaa

35 notes

·

View notes

Video

vimeo

Postmodernism at the V&A from Victoria and Albert Museum on Vimeo.

Postmodernism is the notoriously slippery subject tacked by the V&A's exhibition, 'Postmodernism: Style and Subversion 1970-1990'. This fast-paced film features some of the most important living Postmodern practitioners, Charles Jencks, Robert A M Stern and Sir Terry Farrell among them, and asks them how and why Postmodernism came about, and what it means to be Postmodern.

TRANSCRIPT:

Andrew Logan: Post modernism – yes, I still really don’t understand what post modernism is. I’ve been told many times and it’s been explained to me many times and I still am bewildered. But perhaps that’s part of the movement – bewilderment.

Malcolm Garrett: I don’t think I really know too much about what post modernism actually is. For me, it’s primarily an architectural movement.

Robert A M Stern: Post modernism was a kind of style and it was kind of outrageous style at that.

Zandra Rhodes: I think we’re originals, but it wasn’t until I got spoken to by the V&A that I thought about anything that was post modern.

The way I worked I described as retrievalism.

Charles Jencks: The Independent said do use the word ‘post modernism’ because it means absolutely nothing and everything.

Malcolm Garrett: I called myself a new futurist for a while. So that’s a term I would use rather than post modernism.

Andrew Logan: Well, I suppose I had a very post modernist occurrence – I took acid. Normal things suddenly turned into something extraordinary.

Zandra Rhodes: Well, in 1977 punk was just starting to happen and I thought why not do tears that actually look like tears and then got safety pins and beaded round them like 12 years before Versace.

Malcolm Garrett: I had access to the first photocopier and I was able to modify and change the look of the image using a photocopier.

Peter Saville: And, of course, in the 70s and into the 80s the record cover was this incredibly important, vital medium of visual information. There were the music papers and occasionally the Sunday Times colour supplement might just do something about Andy Warhol in New York and that would be about it.

Paula Scher: In the 70s when I first started designing there was a predominance of the international style where the ultimate goal was to be clean and I always felt that that was like trying to clean up your room. So I was looking for ways of designing typography that could be more expressive, that were not about creating order but were about creating spirit.

Robert A M Stern: Times Square was where we were in charge - the whole revitalisation of Times Square is a very interesting, complicated story, but it does show the difference between the modernist point of view of how to redevelop or to develop a city and what we were able to do …

Charles Jencks: Post modern architecture is really to do with pluralism. You’ll find its depth, all of the great post modernism, the philosophy and now in literature, is about pluralism, pluralism, pluralism.

Robert A M Stern: To say, no, no, it’s a mess, in fact we ought to make it more of a mess. The world comes to Times Square not for tidykins, but for mess.

Charles Jencks: It’s accepting that the modern world with Freud, Marx, Henry Ford, mass production, is positive, but it can be radically improved.

Robert A M Stern: We studied the signage in Times Square and then we set minimums, minimums for sizes of signs, minimums for brightness of signs. What we were legislating in a way the capitalist impulse. Once you tell an entrepreneur that his or her sign can only be this big, he will be satisfied, he will agree with it. But if you say it can be this big or bigger or brighter, well everybody wants to compete in a capitalist society.

Charles Jencks: So you have to be on the one hand ironic about failures, probably the beginning of a new depression, another crisis of modernism, modernisation, modernity. What’s going to get us out of this? We have to re-think the modern movements in all the arts and in society and post modernism is the umbrella term for re-thinking.

Robert A M Stern: We knew 42nd Street was an incredible success when the Consolidated Edison Company called the State of New York and said, you know our grid is zapped out.

Peter Saville: In the case of, particularly, Joy Division and then New Order, they could never exactly agree amongst themselves. There was no hierarchical structure, particularly in New Order after the end of Joy Division, after Ian Curtis had died. The responsibility for the covers came to me and so they were about what I was interested in, they were about in a way beginning to learn the canon.

Carol McNicoll: The thing that I was doing was I was using slip casting. A lot of the Leach tradition and minimalist things also had that idea of expressing the deep, inner, mystic qualities of clay. And I thought that was a load of complete rubbish. And I thought what was wonderful about clay was the fact that you could make it look like anything else.

Peter Saville: They decided to call their first album “Movement”. The sequences and the pulse beat - there was a subtle transition from Joy Division to New Order and they had to find who they could be without Ian’s writing and without Ian’s singing. The pulse beat begins to become what New Order are about. I was quite happy to show New Order futurism because I was certain that Marinetti would have loved New Order.

Deyan Sudjic: Charles Jencks wrote this extraordinarily resonant sentence in ‘Post Modernism’ in which he said that modernism died in 1972 when Pruitt-Igoe was blown up.

Charles Jencks: In fact it goes back to the 60s really, in a radical way. Feminism, black power, a whole series of issues all over the world.

Terry Farrell: I think it was a release from constraint from the design codes – design as a function of the modern era.

Peter Saville: The notion of a singular aesthetic is untenable, is entirely unrealistic in a democratised society.

Terry Farrell: As such it was a Pandora’s box, the genie was out, so it’s about colour and ornament and try anything.

Robert A M Stern: If you take the actual broader, philosophical meaning of post modernism, there are no absolutes in art whether it’s architecture, painting, music, literature or whatever.

Terry Farrell: It’s a shift that brought the internet, the web – things were never the same again.

Reinhold Martin: During the - one of the high moments of modernism, the constructive period, artists like Varvara Steppanova and her colleagues, Rodchenko – the productivists. They were designing the way that they imagined the proletariat – the newly empowered and politicised proletariat - would dress. And the interesting question might be: What’s the difference between an Issey Miyake or a Commes des Garçons iteration of modernism? Can you imagine that garment in relation to political revolution? Probably not. You can imagine it as a kind of citation and if there is a thing called post modernism, it’s the absence of that thought. Can you imagine the Comme des Garçons worker? If the answer is no, then you’re in the world of post modernity.

Peter Saville: When Ian died, a kind of - the legend was sort of forged, almost overnight. The message of this story was more profound than any broadcast or marketing could ever be.

Carol McNicoll: One of the things that’s particular about the English tradition is that it’s very impure. Yes, we had an empire, we were forever nicking ideas from other places and kind of collage-ing them together.

Iain Sinclair: You’d have a piece of London that’s pre-Fire of London, that happens to have survived, right next to something that came in as a Christopher Wren development, something that came through the railway age, a cottage that’s hung on until it’s wiped out to put up a Westfield shopping mall, and all of these things co-exist.

Sam Jacob: That combination of complete victory of the neo-liberal economy alongside the diversity of culture, diversity of interests, I think makes it a place where things happen in a post modern way.

Iain Sinclair: And it all meshes on somewhere like the Thames, the reason for London’s foundation, that we come ashore from elsewhere and we reinvent ourselves by bringing people in that keep the culture alive.

0 notes