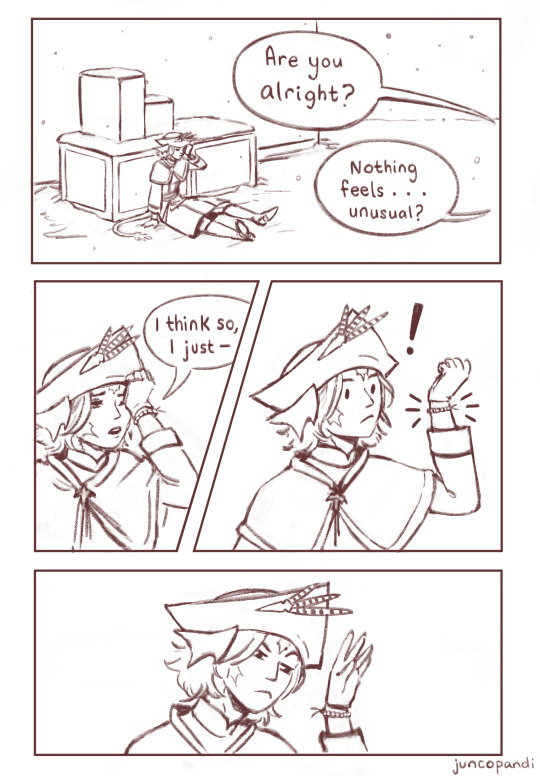

#and the unnamed scions are off stage right

Text

ok uh a party finder chat from a few weeks ago planted this idea in my head and I couldn't stop thinking about it. hope you enjoy xx

#final fantasy xiv#final fantasy 14#endwalker#endwalker spoilers#ffxiv spoilers#in from the cold#warrior of light#au ra wol#zenos yae galvus#kind of. he's off screen.#and the unnamed scions are off stage right#honestly i thought of NMES4EVR and couldn't grab my tablet fast enough

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: America Is Trembling: Jean Genet’s Answer to Donald Trump

Richard Avedon, “Jean Genet, writer, New York, March 11, 1970” (1970) (courtesy Avedon Foundation)

“What is still called American dynamism is an endless trembling.” That is Jean Genet’s prophetic declaration, written for a speech he delivered on May 1, 1970 at Yale University, before an audience of approximately 25,000.

In the wake of November’s election and yesterday’s swearing-in of President Donald J. Trump, this American “trembling” is so resounding that, 46 years on, Genet might slyly smile – or smirk — were he alive to see it.

We felt the trembling straightaway. We heard it in Trump’s racist hysteria about Mexicans in the summer of 2015. We saw it in the new President-Elect’s stupefied anxiety as he sat beside President Barack Obama in the White House on November 10, 2016. And the trembling was everywhere post-election, on the sidewalks and in the subways, in bedrooms and conference rooms, and in the faces of hoodwinked power brokers leaving Trump Tower. Remember wobbly Mitt Romney and the disconcerted Al Gore? The spooked Silicon Valley industry leaders and the humiliated gathering of news anchors?

Even former sycophants like Rudy Giuliani and Chris Christie trembled their way off the national stage. And still there is this trembling – a quaking among a docile but perturbed intelligentsia and a shuddering among the increasingly stifled presidential press corps. To say nothing of those legitimately shaking in fear about the potential cancellation of their Obamacare and Social Security and Medicare, or the coming legalized assaults to reverse their hard-earned civil rights, or their possible deportation. And the unspoken trembling about a Tweet-triggered nuclear showdown.

Still Genet’s comments from 1970 go further than predicting the current American trembling. This fearfulness, this state of general cowardice, is in his view, part of the reason why morons and goons end up running things: “Everyone [in America] trembles before everyone else” adding, “the strongest before the weakest and the weakest before the most idiotic.” If there’s a cure implied here, it’s that the strong need to stop cowering so that the weak and the foolish can be thrown out of power.

But since the very opposite has just happened, it might make for a distracting and instructive parlor game to imagine what Jean Genet would make of the ongoing American trembling he detected back in 1970.

Students in a line, holding hands during May Day demonstrations. Photographs used in the publication of the Yale Alumni Magazine, ca. 1917-1973 (inclusive) (courtesy Manuscripts & Archives, Yale University)

There are clues throughout his work. In his incendiary wartime novel Funeral Rites (1948), the collaborator Riton is willingly sodomized by a Nazi lover on a rooftop in occupied Paris, a national debasement Genet echoes years later in an interview in which he ridicules Adolph Hitler as the “Austrian corporal,” who brings a cowardly France to its knees. Genet’s drama The Balcony (1957), about the playacting and masochism of authority figures, is set in a posh brothel during a revolution in an unnamed country. Watching the news these days seems like watching that play’s revival. What would Genet make of an ingenious con man from Queens, the hapless scion of a racist developer, sworn in as President of the United States? How would he render, for the theater of the absurd, this bankrupt innkeeper who got a second chance by roleplaying his fictitious alter-ego on national television and then cashed in on his celebrity to take over the executive branch of the U.S government, as if that prize were some second-rate New York hotel? And Genet could easily unpack Trump’s fixations — about President Obama’s Kenyan patrimony, about the appeal of a Russian autocrat, and even about Trump’s self-mythologizing link between small hands and large genitalia. Most fitting for a Genet-like takedown is Trump’s messy empire, expertly tailored by its maker to showcase late capitalism’s ritualized sadism — from its pencil tower buildings and power neckties to his beauty contest carnivals and reality TV puppet shows.

Cover of playbill for stage production “The Blacks” by Jean Genet (via digitalcollections.nypl.org)

Genet’s writings uncover the perverse anarchies that operate within well-ordered hierarchies. He thought money was inherently evil and that the quest for power was a form of necrophilia. Many writers also had their finger on the overlooked diseases underlying postwar Western culture. But Genet, when he first visited the United States, was an internationally famous writer approaching the age of sixty who had a range of personal experiences that especially qualified him to detect America’s trembling.

Born in 1910, Genet was the orphaned son of a prostitute, the former ward of the French state, an erstwhile thief, vagrant and hustler who had spent nearly six years off and on doing time in various prisons, surviving, inside and outside their walls, among the most elaborate and dangerous of what we would today simply call “bullies”: jailhouse rapists, renegade Nazis, cross-dressing murderers. Genet’s highly stylized, sexually explicit works in memoir, fiction and playwriting transformed each of those genres, scandalizing readers and audiences and turning him into one of the most exasperating and profound moralists of the twentieth century. Late in his career, facing a decade-long writer’s block, his writing was reborn, first by engaging with the visual arts and, later, through writing about aspiring revolutionary groups who were fighting power from the margins. Little wonder, then, that by the late 1960s he was drawn to the trembling that was shaking the United States.

Jean Genet at the May Day Rally (photo © John T. Hill)

And so, in the summer of 1968, he entered the country illegally through Canada to cover, along with Terry Southern and William Burroughs, the Democratic National Convention in Chicago for Esquire. According to Edmund White’s biography, among many audacious acts, the older Genet, caught up in the state violence against protestors, stared down a rifle-toting National Guardsman and reassured the injured victims, many of them white kids who had never encountered police aggression. Covering the extended fiasco, Genet was a witty provocateur, denouncing the political convention as “gaudy and meaningless,” dismissing the Yippie icon Abbie Hoffman as “not bad for a professional” and, to Esquire’s outraged countercultural readership, praising the “divine” and “athletic” musculature of Chicago cops.

Man holding Black Panther flag behind police line during May Day demonstration. Photographs used in the publication of the Yale Alumni Magazine, ca. 1917-1973 (inclusive) (courtesy Manuscripts & Archives, Yale University)

Two years later, when Genet again entered the US illegally, the reactionary winds were blowing even stronger. This time he came mainly to advocate on behalf of the Black Panthers. And while a degree of homoerotic attraction fueled Genet’s initial interest in the Panthers’ paramilitary aesthetics, by 1970 Genet was savvier about American-style forms of power and state violence than he had been two years earlier. And the context of that time resembles the possibilities America faces after yesterday’s inauguration.

The law-and-order, paranoiac US President Richard Nixon had defeated a splintered Democratic Party in the ‘68 election and, by the time Genet returned in ‘70, Nixon had secretly escalated the war in Vietnam and begun blacklisting members of the press. Opponents were being spied upon; dissenters were labeled “terrorists.”

Genet, too, was on Nixon’s radar. Even when he was in Paris, the FBI had been monitoring the writer’s associations with American civil rights leaders. Under the supervision of Vice President Spiro Agnew and COINTELPRO, the Black Panthers were being targeted for elimination and the Party members were engaged in deadly shoot-outs with local police forces. The Party’s leader, Eldridge Cleaver, was living abroad in Algeria. One of its founding members, Bobby Seale, the sole African-American, was one of the original “Chicago Eight” before he was charged with contempt and removed from the proceedings, reducing the number to the “Chicago Seven.” Seale had been disgracefully bound, gagged and trussed in the courtroom in full public view. And it was at the height of this turbulence that Genet delivered his May Day speech at Yale University.

Jean Genet and Elbert Howard at the May Day Rally (photo © John T. Hill)

The speech, read in its English translation by a founding Black Panther member, Elbert “Big Man” Howard, consists of a rousing appeal on behalf of Bobby Seale, who was then on trial in New Haven for murder (the charges were eventually dropped). Genet’s oratorical strategy, a full-scale assault on the toxic apathy of white liberals, remains prophetic.

Genet blames the prevalence of racism on his Yale audience. “It is very clear that white radicals owe it to themselves,” he declares, “to behave in ways that would tend to erase their privileges.” Closing on a provocative note, he further goads the audience by comparing universities to “comfortable aquariums […] where people raise goldfish capable of nothing more than blowing bubbles.” Reread in light of the response to controversial police killings of African Americans in Charlotte, Ferguson, and elsewhere, Genet’s words bluntly spell out the diplomatically stated ideas coursing through the Black Lives Matter movement.

As relevant as those remarks on racism are to today’s situation, Genet’s extended “appendix” to the May Day Speech, first published in a special edition by City Lights Books, represents a wider confrontation with white neoliberals and their snug institutions.

Jean Genet, “May Day Speech” (1970) (© City Lights Books)

In the appendix, Genet broadens his offensive, declaring that the United States must acknowledge an inbuilt national “contempt” dating back to the country’s founding. Unless the nation owns up to this contempt, which “contains its own dissolving agent,” then that denial will cause “American civilization” to, quite soon, “disappear.”

And then he calls out those he sees as the enablers of this ongoing American contempt. First in his line of fire is an American press so prone to “lies by omission, out of prudence or cowardice” that even “New York Times lies” and “the New Yorker lies.”

As for colleges — those supposed hotbeds of tenured radicals — Genet presciently observes that inside American universities, the “only recognized values are quantitative” and thus our schools “turn [students] into a digit within a larger number” and cultivate in them “the need for security, for tranquility and quite naturally [professors] educate you to serve your bosses and beyond them, your politicians, although you are well aware of their intellectual mediocrity.”

And beyond this liberal collaboration with a culture of contempt, Genet sees an increasingly armed and alienated police force who “provoke fear” and yet who themselves “tremble” within this overall American shuddering.

No trait was more nauseating or, as Genet would have pointed out, more pompously flaunted by Trump’s presidential campaign than its unadulterated contempt: for women, for non-whites, for the disabled, for the press, and, ultimately, for the US Constitution. And yet it was the disdain of prosperous neoliberals for underpaid workers and the working poor that made Trump’s more schematized hatred more enthralling to his voters.

Genet’s May Day Speech offers no direct solutions to our current nightmare cycle of contempt. Certainly his analysis proved immediately true in 1970. Three days after Genet delivered his speech and fled the country, students protesting Nixon’s widening of the Vietnam war into Cambodia were killed by Ohio National Guardsmen at Kent State University. The rest of Nixon’s vulgar legacy is well-known and its wretched example inspires a good deal of the current President’s crude and effective stagecraft.

Perhaps Genet, being an avid reader of both Mikhail Bakunin and Marcel Proust, and thus both an anarchist’s anarchist and a writer’s writer, left the solutions for America’s trembling to the country’s own imagination.

Jean Genet’s signature (via Wikimedia Commons)

Maybe, as an expert con artist, Jean Genet assumed that language, if used with the right combination of refinement and cogency, could elicit a reckoning, just as his writing’s resolute, lyrical reenactments of real and imagined experiences validated his existential truths. If so, then, we might mimic Genet’s aggressive exactitude and ask ourselves questions that go deeper than the banalities of Sunday morning chat shows or yesterday’s forgotten tempests in a tea pot. Structural questions like: what kind of knowledgeable electorate can a nation cultivate while its primary news channels remain owned and overseen by entertainment empires such as 21st Century Fox, Time Warner, Walt Disney and Facebook? And what forms of confrontation could undo the insanity of the US Supreme Court’s decision to legalize political bribery through its Citizens United ruling?

And, finally, how to replace a two-party system representing a single power structure manipulated by financiers and bankers, one that recently fielded, on the one hand, a former childhood poverty advocate turned Wall Street motivational speaker and, on the other, a real-estate magnate who still produces a television show designed to fulfill its viewers’ need to normalize and enjoy a dehumanized economy?

Genet, a playwright and a hustler, could have easily seen through theatrics as cheap and nihilistic as Trump’s. Forced into that spectacle for the foreseeable future, the nation trembles at the potentially horrifying absence behind the role the man has been playacting. “The essence of theatre is the need to create not merely signs,” Genet writes, “but complete and compact images masking a reality that may consist in absence of being.”

The post America Is Trembling: Jean Genet’s Answer to Donald Trump appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2j7iob2

via IFTTT

1 note

·

View note