#archietctural history

Photo

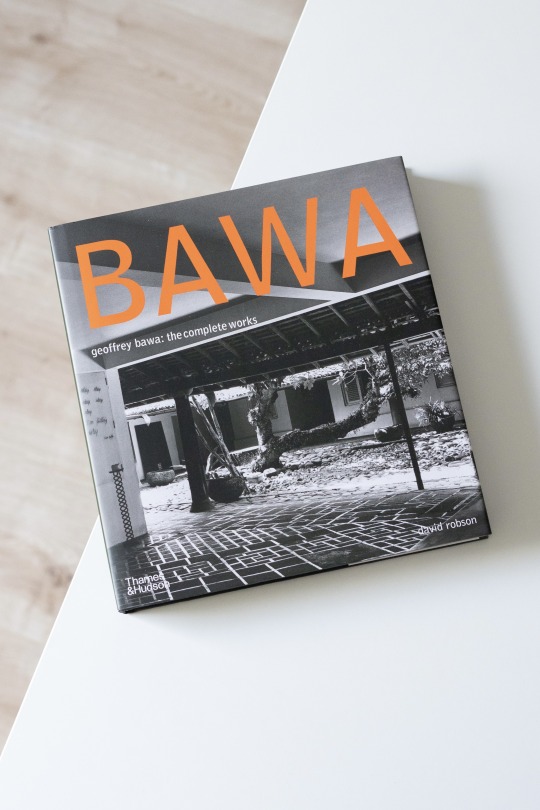

Geoffrey Bawa (1919-2003) definitely was a late bloomer with regards to architecture: it was only at the age of 33 that Bawa decided to commit himself to architecture and took up studies at Architectural Association in London. Up to that point Bawa had already studied English and Law in Cambridge but through the purchase of a run down estate in his home country got in touch with architecture: trying to renovate and convert its garden into an Italian garden Bawa realized his lack of skills, a realization that led him to an apprenticeship in the office of H.H. Reid and ultimately the architecture studies in Cambridge where he graduated in 1956. Upon returning to then Ceylon (Sri Lanka since 1972) he formed his own office from the leftovers of his mentor H.H. Reid’s. In 1962 Bawa was joined by the Dane Ulrik Plesner who would become his long-term partner and with whom he realized some of his most important buildings. Combining the modernism he was exposed to at Architectural Association and Ceylonese architecture, both traditional and colonial, Bawa developed a unique idiom tailored to the particular local climate and building techniques.

In order to get to know and understand Bawa’s architectural oeuvre the present monograph still is the best starting point: David Robson’s „Geoffrey Bawa - The Complete Works“, published in 2002 by Thames & Hudson, an ideal blend of biography and work analysis. By means of countless photographs, plans and occasional models the reader gets to understand the fundamental connection between Bawa’s architecture and site as well as his absorbance of the respective genius loci (with the latter extending to a sensitive landscaping as well). Robson’s book is an excellent read, lavishly illustrated and at any time insightful.

#geoffrey bawa#monograph#architecture#sri lanka#architecture book#thames and hudson#archietctural history#book#tropical modernism

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kasteel Ooidonk, Deinze, East Flanders, Belgium

#art#design#archietcture#castle#kasteel#kasteel ooidonk#belgium#deinze#east flanders#luxury house#luxury home#luxury lifestyle#style#history#country house

613 notes

·

View notes

Text

Six films to watch during London's first architecture film festival

The inaugural ArchFilmFest is now underway in London, and Dezeen reporter Eleanor Gibson has selected her top picks – ranging from an insight into the life of ageing architect Gottfried Böhm to a look at the tech infrastructure of New York's art-deco buildings.

Dezeen is media partner for ArchFilmFest London, which takes place from 6 to 11 June 2017 in two locations, the ICA and the Bargehouse at Oxo Tower Wharf, and will include 60 hours of screening.

The theme of the six-day-long event is Scale, which led its founders – architect Charlotte Skene-Catling and designer Manuel Toledo-Otaegui – to divide up the content into size-related categories. These are The Room, The Set, The Tower, The City and The Planet.

Chile is the partnering country for the festival, so the opening movie screened last night was the UK premier of Bruno Salas' Escape de Gas. The film traces the history of Chile's 1972 UNCTAD III building, now known as GAM.

Other sections focus on more specific aspects, like the work of legendary filmmaker Julien Temple and African architect Diébédo Francis Kéré, who has been selected to design this year's Serpentine Pavilion.

An exploration of the late architect Zaha Hadid and her legacy and Ben Wheatley's High Rise, a movie based on JG Ballard's dystopian novel, will also both be screened during the event.

A series of workshops, symposiums and parties will take place in conjunction with the event. A prize will also be awarded to the best experimental short film.

Here are our picks for the top six movies to watch:

Francis Keré: An Architect Between by Daniel Schwartz

Bareghouse Room 11, Friday 9 June, 3.40-5.30pm

19 minutes

As part of a trio of documentary films celebrating architect Francis Kéré, Daniel Scwartz's focuses on seven projects by the African architect.

By exploring Kéré's work, both in his native Burkina Faso and other countries, Scwartz aims to show how archietcture has become more socially driven, with a focus on issues like sustainability, poverty and climate change.

Concrete Love – The Böhm Family by Maurizius Stakler-Drux

ICO, Saturday 10 June 2017, 8.30-10.30pm

88 minutes, German with English subtitles

This intimate tale follows 93-year-old Gottfried Böhm, a German architect known for his concrete buildings. Böhm was born into a family of architects and then had three sons, Stephan, Peter und Paul, who became architects.

As well as exploring German architecture across the generations, the film uncovers a complex relationship between the father and his sons as they seek independence, but also come to terms with the loss of their mother Elisabeth.

Fragments on Machines by Emma Charles

Bargehouse, Room 11, Wednesday 7 June and Thursday 8 June, 4.45-5.30pm

17 minutes

Taking its named from a Karl Marx text on the relationship between man and machine, Fragments on Machines unveils the physical aspects of the Internet.

Produced by long-term Dezeen collaborator Emma Charles, the film has a fictional storyline that threads together spaces inside art-deco buildings in New York, with a focus on elements like fibre-optic cables, computer servers and ventilation systems.

Souvenirs de Iasi (Iasi Memories) by Romulus Balazs

Bargehouse Room 11, Saturday 10th June, 3.50-4.45pm

54 minutes

Shortlisted for the festival's experimental films competition, Romulus Balazs' Souvenirs de Iasi tells the lesser know story of Romania's role in the Holocaust.

Balazs revisits the locations of photographs that were taken 74 years ago during a massacre in a Romanian city, with the aim to discover the nature and scale of deportation and extermination of Jews living in Romania during the second world war.

The Infinite Happiness by Beka & Lemoine

Bargehouse Room 13, Friday 9 June 2017, 1.30-3pm

85 minutes, English and Danish with English subtitles

As part of the Scale selection, The Infinite Happiness explores the 8 House, the figure of eight housing block in Copenhagen designed by Danish architect Bjarke Ingels, through personal stories of those who have connected with the building.

Different anecdotes are stacked together "like a game of lego" to explore how and why the looping housing block is so successful in fostering happy communities.

London Modern Babylon by Julien Temple

Bargehouse Room 3, Wednesday 7 to Sunday 11 June 2017, 11am-6pm

125 minutes, English

Julien Temple's London Modern Babylon, which he completed in 2012, explores how London has changed over the last 100 years, through a tapestry of its inhabitants, including musicians, writers, artists and thinkers.

The film will be screened inside the Temple of Temple room, an installation dedicated to the legendary British director, which will showcase a rotation of three of Temple's films throughout the festival.

The post Six films to watch during London's first architecture film festival appeared first on Dezeen.

from ifttt-furniture https://www.dezeen.com/2017/06/07/six-films-to-watch-during-architecture-film-festival-archfilmfest-london/

0 notes

Photo

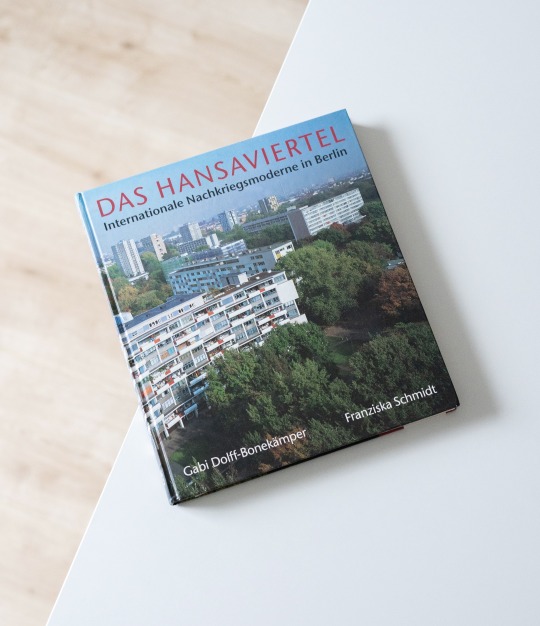

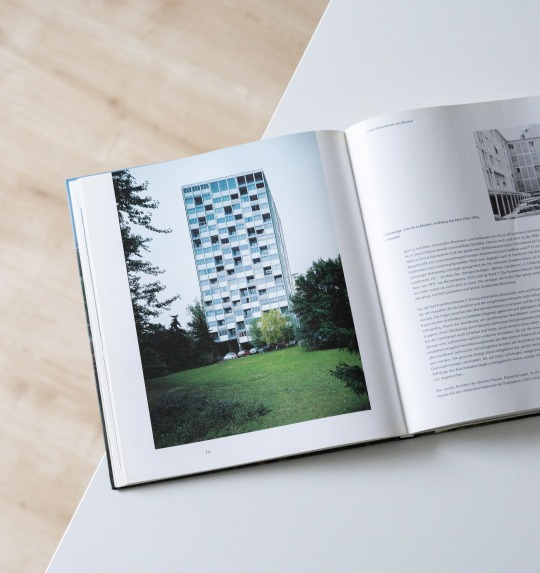

Only 12 years after the end of WWII the 1957 Interbau building exhibition gathered progressive international and German architects in Berlin to design houses, apartment buildings and infrastructural architecture for the Hansaviertel which had been almost entirely destroyed by the war. The Interbau dates back to 1951 when the Senate of West-Berlin contemplated the idea of having a building exhibition draw attention to the city and respond to the construction of the Stalinallee in East-Berlin. After a jury had selected Gerhard Jobst’s and Willy Kreuer’s town planning design among 98 competition entries a roster of potential architects was drawn up, among them International masters like Arne Jacobsen, Oscar Niemeyer and Walter Gropius but also Egon Eiermann, Sep Ruf or Paul Schneider-Esleben as representatives of German postwar modernism. The resulting quarter ultimately comprised 1,300 housing units, a library, a shopping center, two churches and a day care center.

Still the best overview of the Hansaviertel’s history and architecture provides the monograph “Das Hansaviertel - Internationale Nachkriegsmoderne in Berlin” by Gabi Dolff-Bonekämper and photographer Franziska Schmidt, published in 1999 by Verlag Bauwesen. Divided into two distinctive parts the book provides a comprehensive account of the events leading up to the 1957 Interbau, the underlying urban planning as well as the architects involved. Interestingly the authors have also included a collection of international reactions to the Interbau, largely positive and affirmative of the initiator’s intention to reestablish Germany on the stage of international progressive architecture. The second and larger part of the book is then dedicated to the architecture: structured along tours Dolff-Bonekämper explores the different parts of the quarter and with the help of plans and Schmidt’s photographs examines each building in great detail. Since she also covers buildings (the school, the Haus der Kulturen der Welt and the Unité d’Habitation) related to the Interbau but located outside the Hansaviertel a complete picture of the new Hansaviertel and the many innovative buildings emerges. A great read!

#interbau 1957#archietctural history#nachkriegsarchitektur#nachkriegsmoderne#architektur#berlin#architecture book#book#monograph

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It is both meritorious and tragic that Detlef Mertins spent the decade before his untimely death in 2011 with writing the present monograph: „Mies“, published in 2014 by Phaidon. Countless books have been written about Mies van der Rohe and one might ask whether yet another monograph really was necessary. After finishing Mertins’ book at the latest this question can only receive one answer: yes! The author, a meticulous researcher knowing all of Mies’ buildings and having read everything that’s been written about him, in his well-balanced work biography portrays Mies as a man of duality. While his major works, especially those in the US, in their austerity and single-mindedness appear like having sprung from a very certain and rigid mind, Detlef Mertins shows that this is not entirely true. Rather, Mies under the influence of philosophy in general and Nietzsche in particular certainly had doubts about life and the modern condition. What he gained from it though was to live life as what the philosopher called an „adventure of the soul“ and with his architecture, as Mertins explains, he nurtured this adventure. Through openness and universality he sought to liberate and reconnect people with the surroundings, no matter if townscape or landscape, a goal that against the background of the Farnsworth house or the Neue Nationalgalerie in turn required compromises and certainly forced clients into experiment and adventure. What’s more is that Mertins also gives ample thought to Mies’ collaborators Lilly Reich, Ludwig Hilberseimer or Myron Goldsmith and shows how they influenced him, how they contributed to his work and how they helped him realize his vision of architecture.

Naturally these brief insights only provide a glimpse of just how rich, serious and knowledgeable “Mies” is. Detlef Mertins’ book surely is a at times challenging read but also one that rewards with brilliant analyses and ultimately a definitive account of Mies van der Rohe’s life and work.

#mies van der rohe#monograph#detlef mertins#phaidon books#architecture book#book#archietctural history

52 notes

·

View notes