#bioarchaeology of adolescence

Text

The floor is hella cold but I couldn’t work sitting anywhere else. While I’m reading for my PhD proposal I’m attempting for the fist time to crochet myself a sweater. Crafting is my way to relax after a long day in the lab.

Also, since this is the Archaeology hashtag I’m sharing cute 6th century CE mosaics from the city of Ravenna, which I visited a few weeks ago. I’m a bit of a nerd about late antiquity and the Romano-barbaric interaction, I info-dumped my girlfriend for the whole trip. Bless her she puts up with me and my fascination for the Ostrogoths!

#archaeology#bioarchaeology#anthropology#physical anthropology#art#bioarchaeology of adolescence#bioarchaeology of childhoood#studyblr#archaeology of childhood#study#crafts#crochet

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The mistaken claim that Amazons must have received their name because they were single-breasted was widely repeated by Greek and Roman writers, and every author thereafter is obliged to grapple with the paradoxical image. A fiction invented in the fifth century BC was behind the notion. This fake “fact” surfaced at least two centuries after the tribal name “Amazon” for an ethnic group of men and women was used by the Greeks (chapter 1). The historian Hellanikos of Lesbos (b. 490 BC) described Amazons as “a host of golden-shielded, silver-axed, man-loving, boy-killing females.” Then Hellanikos attempted to make their foreign name “Amazon” into a Greek word. The Greeks were fond of this sort of etymological exercise of forcing Greek meanings onto loanwords from other languages, based on similarities to sounds in Greek. The strong tendency of ancient writers to create and accept crude, “patently absurd” word derivations is well known.

In this case, Hellanikos maintained that Amazones must mean “breastless” or “lacking breast” because a- means “without” in Greek and mazos sounded to Greek ears a bit like mastos, the Greek word for “breast.” A rival folk etymology suggested that the name meant “without grain,” because maza was Greek for “barley.” The Scythian nomads were in fact meat-eaters, not vegetarians, but this dietary label was much too dull to compete with the lurid image of women who sacrificed their breasts to become warriors. Hellanikos’s false etymology demanded a story to explain the Amazon’s missing breast. Various dreadful scenarios were proposed for the method of this alleged self-mutilation, which was based solely on specious wordplay.

Airs, Waters, Places, a treatise attributed to the physician Hippocrates (fourth century BC), stated that Sarmatian women seared the right breast of baby girls with a red-hot bronze tool, so that the right arm would be stronger. The idea here was that the potential power of the breast would be displaced to the corresponding arm. It is physiologically true that handedness often corresponds to slightly larger hands and feet on the dominant side of the body, and that habitual exercise of one limb or hand can result in development of larger bones and musculature. (As noted in the previous chapter, bioarchaeological signs of right-handedness and larger finger bones among archers have been ob- served in the skeletal remains of warriors of both sexes in burial sites across Scythia.) Hellanikos and Hippocrates were contemporaries of Herodotus, our earliest and most accurate Greek source of detailed information about Sarmatians, Scythians, and Amazons based on his firsthand observations and interviews around the Black Sea in the fifth century BC.

Significantly, however, even though Herodotus describes many gruesome and extraordinary Scythian customs, he never mentions this self- inflicted breast deformity. Nevertheless, the idea took hold. Diodorus, Strabo, Pomponius Mela, Justin, and Orosius repeated the tale that Amazons used an iron tool to cauterize the breast at infancy or before pu- berty so that it would not hinder their use of the bow and spear. Pomponius Mela said that removal of the right breast made them “ready for action, able to withstand blows to the chest like men.” According to Apollodorus and Curtius, Amazons “pinched off” the right breast but retained the left for nursing their babies. Arrian described Amazons who came to join Alexander’s campaign in Persia (330 BC); to him, the right exposed breast appeared to be smaller than the covered left breast (see chapter 20).

We know that at least three later writers disagreed with the one-breast notion. John Tzetzes, the Byzantine commentator on Hellanikos, pointed out that the etymology was untrue because cutting off a breast would cause fatal bleeding. Another author, Philostratus (third century AD), rejected Hellanikos’s claim and proposed a more logical—and more humane—explanation, that amazon actually meant “not breast- fed.” Philostratus argued that real-life Amazons love their children but do not nurse them because the practice results in mollycoddled children and saggy breasts, undesirable traits in their warrior culture. Instead, the nomadic horsewomen nourish their babies with mare’s milk, honey, and dew. Tryphiodorus, a Greek poet of the fifth century AD, also defined amazon as “unsuckled.” Such a concept was far removed from Greek culture, with its stay-at-home nursing mothers, but seemed reasonable for nomadic hunter-warrior women.

A similar practice appears in a sixth-century AD Roman description of a northern nomad tribe called the Scrithiphini (probably the Sami people of the western Arctic region) whose women and men hunted together. According to Procopius, their infants were not nursed but fed with bone marrow and swaddled in cradle boards hung on trees while the mother and father pursued game. Once the sensational “factoid” of one breast became embedded in the catalog of Amazon attributes, each successive writer routinely included it in his description of the women warriors. Perhaps the concept seemed appropriate because Amazons represented the opposite of Greek wives and mothers, and their “terrifying asymmetry” signaled their barbarism.

Some modern scholars suggest that deliberately removing one breast was intended to symbolize the Amazons’ willful destruction of their own femininity and so resonated with Greek men who feared women who behaved like men. For Greek women, the removal of one breast would signify the terrible sacrifice Amazons made to become more like men. For other scholars “one-breastedness” signi- fied Amazons’ freedom from nursing and maternal attachments: Amazons “don’t need breasts because they will never raise children.” But many ancient Greek texts described Amazon mothers, and some referred to nursing babies (not to mention the archaeological discoveries of female warriors buried with children; chapter 4). According to another theory, Amazon “breastlessness” stood for the “sexual unripeness of the nubile adolescent” Greek maiden. Some scholars point out that Greeks associated the right side of the body with masculinity and the left with femininity. Most classical writers described removal of the right breast while the left was exposed, but some reversed the sides. And Greek artists were inconsistent about which of the two breasts was exposed in Amazon battle scenes.

If the concept of removing a breast was such an important symbolic attribute for the Greeks, then one must wonder why no single-breasted Amazons appear in classical art. Despite the popularity into modern times of “just-so stories” about how the Amazon “lost her breast,” ancient Greek painters and sculptors invariably depicted the mythic Amazons double-breasted. As noted, symmetry was an essential quality of the Greek ideal of beauty. Amazons of myth and art were always portrayed as beautiful heroic women, the equals of the handsome aristocratic Greek heroes. Perhaps physical asymmetry in artistic scenes would be jarring to Greek aesthetic sensibilities. (Ugly or deformed people appear in artistic illustrations of ancient comedies or scenes of daily life but are rare in heroic situations.) Moreover, artistic portrayals of Amazons are often erotic—showing mutilated women could interfere with sexual appeal.

Vase painters and sculptors often emphasized Amazons’ bosoms with diaphanous drapery or body-hugging garments. Another artistic “convention” was to show fighting and wounded Amazons in chitons (loose, short, belted tunics fastened at the shoulder—also worn by Greek males) worn in exomis style, with one breast and shoulder exposed. Art historians have interpreted this typical Amazonian pose in many different ways. Was revealing a breast an erotic gesture? Was the “one breast exposed” intended as a subtle, less graphic stand-in for the “one breast missing” literary motif ? Was a bared breast meant to evoke sympathy, in the case of wounded Amazons? Was flaunting the breast in the midst of battle a way of taunting or distracting the male heroes, or was it to make sure the men (and the viewer) understood that they were being attacked by women? In fact, one exposed breast reflected practical active attire. The archer goddess Artemis and the huntress Atalanta were dressed for action this way, and so were many Greek male archers, workers, warriors, and heroes. In Greece and other ancient cultures, the dominant shoulder of active figures was often left unclothed for freedom of movement.

Apparently Greek artists and their audiences were not persuaded by the literary trope that female archers were hindered by their breasts. But if artists never depicted one-breasted Amazons, why did the idea catch on and persist so stubbornly in Greek literature? Did some ancient cultures really practice breast removal or suppression? Was there some exotic custom or mode of dress that could have been misunderstood in antiquity, leading Greeks to believe reports of “breastless” or “single- breasted” women warriors? An atrocious practice in West and Central Africa today results in the maiming of millions of young girls by their mothers who hope to prevent rape. “Breast ironing” involves cauterizing budding breasts with a heated metal tool to inhibit breast development. Is it possible that travelers’ tales of similar African “breast-searing” customs were known to the writers of the Hippocratic texts and projected onto Sarmatian women and Amazons of Scythia?

There is no way of knowing how ancient this “secret” ritual of Central Africa really is, and in the absence of any other evidence the likelihood of a similar practice in ancient Eurasia seems slight. Nonetheless, the coincidence is striking, given that several ancient Greek sources mention the use of a heated metal tool. A fictional romance written in Egypt by Dionysius Skytobrachion, about Amazons transported to a Libyan setting, included ethnological details from North Africa to give local flavor to his tale (see chapter 23). When girls were born to the Amazons, he wrote, “both their breasts were seared so that they would not develop into maturity, for they thought that projecting breasts were a hindrance in warfare [and] this is why they are called by the Greeks Amazons.” He is the only ancient author to say both breasts were cauterized, as in modern reports of breast ironing. Did the author know of an African breast-searing custom? The answer is unknown.

A less violent, practical ethnological tradition of “breast suppression” for the comfort of horsewomen existed much closer to home—in the heart of ancient Amazon territory. Since antiquity girls and women of the Black Sea–Caucasus were trained to be expert archers and riders who hunted and fought. Ethnographic evidence among Circassians, Ossetians, Adigeans, Karbardians, Abkhazians, and other groups points to a long tradition of “flattening the breasts during maidenhood.” When girls were seven to ten years of age, their mothers laced a leather vest or corset around their chests, to suppress movement when the girls were riding and shooting. The leather corset was worn until marriage. On the wedding night, the groom slowly, patiently unlaced the fifty-some ties to demonstrate his love, respect, and self-control. Early European travelers in the Caucasus described this traditional article of young women’s attire, which later became known (and modified) as the “Circassian corset.” In the Caucasus, commented the German historian Julius von Klaproth in 1807, “young unmarried females compress their breasts with a close leather jacket, in such a manner that they are scarcely perceptible.” Archaeologist John Abercromby remarked in 1891,“There is nothing improbable in believing that the Caucasian custom has a long row of centuries behind it.”

One of the Nart sagas refers indirectly to the custom of enclosing the torso of girls in leather corsets. In one saga the hero Warzameg mocks a young woman for having “breasts like old bouncing pumpkins.” The simile reveals Caucasian cultural values, notes the Nart saga translator John Colarusso. Ridiculing large, unrestrained, bobbling breasts was meant as a great insult. Among horse peoples of the Caucasus, swinging, pendulous breasts were considered unsightly and awkward “for one simple reason.” Colarusso explains: “If a woman were to go galloping on her horse across the steppes with large breasts unconstrained, she would be uncomfortable and in pain from their bouncing. So there was a premium on small, firm breasts” for active outdoorswomen. Notably, in the 1920s, European and American women’s new liberated, active lifestyle coincided with tight bandeaus to minimize the chest and flatten the breasts into a boyish silhouette.

Athletic women of most body types tend to favor some sort of bosom support, and modern mounted archers wear tight bodices. It’s reasonable to guess that in antiquity, most female riders, archers, fight- ers, and athletes bound or supported their breasts in some fashion. “Support, binding, or restraint, or some form of sports bra for riding” was probably used by mounted nomad women. Greek artists often depicted Amazons with tight-fitting tunics and diagonal chest bands that may have functioned something like a modern “cross-your-heart” brassiere, notes one art historian. Was there any other special attire that could have been misunderstood by the Greeks as “breastlessness” in antiquity? In vase paintings, many Amazons are clad in cuirasses (rigid bronze breastplates), scaled armored tunics, laced corselets, and upper garments and straps, much like those worn by men and all of which had a “flattening effect”.

These artistic depictions reflected the chest armor of padded or rigid materials and scaled armor worn by real nomad warriors of both sexes in antiquity. Archaeological discoveries in Saka-Scythian-Sarmatian lands have turned up a variety of armored tunics fashioned from horn, hooves, bone, and small gold plates or scales in the graves of both men and women (chapters 4, 12, and 13). Baldrics (diagonal chest straps) and wide belts of leather with gold, bronze, and iron plates were also common in male and female burials. If the Greeks observed fighting women clad in protective chest armor that looked just like male armor, the flat-chested effect would help explain descriptions of “breastless” Amazons.

Modern “Amazon” fantasies often picture women wearing curvaceous metallic chest armor molded in the shape of breasts, à la Wonder Woman and Xena, Warrior Princess (fig. 16.4). An ancient version seems to be depicted in figure 5.1. But such erotic “breasted” armor is imprac- tical and dangerous. Experienced female soldiers of any era know that breast-shaped metal chest armor would be life-threatening. Why? Because cone-or dome-shaped projections would direct the force of blows of weapons toward the sternum and heart. Even a fall could be fatal, causing the sharp metal separating the breast hollows to injure or even fracture the breastbone. Therefore, armored fighting women in antiquity would have worn padding under chest plates shaped exactly like the men’s, presenting a flat surface or a ridge down the center to deflect blows away from the heart.

In antiquity, some male and female warriors wore heavier armor on one side of their bodies, leaving the other side less protected or exposed, which could give an impression of single-breastedness. As we saw in the archaeology of Scythians (chapter 4), the skeletons of warrior men and women indicated that most battle injuries were on the left side of the body, dealt by right-handed opponents. Heavy armor for a gladiator’s sword arm and shoulder was used in Roman times, especially for the gladiator known as the “Thracian.” Suits of armor with pauldrons, heavy plates protecting one shoulder and arm, were often used in mounted combat. One-sided armor or shoulder padding unfamiliar to the Greeks could have been mistaken for single-breastedness and could account for Arrian’s report of the asymmetrical chests of the Amazons encountered by Alexander.

The notion of single-breasted Amazons—which seems to signal something about a warrior women’s sexuality, willpower, and masculine strength achieved by sacrificing a feminine attribute—has clung to the standard literary description of Amazons for more than two millen- nia. It seizes the imagination because it is gruesome, just as the tale of African mothers who cauterize their daughters’ breasts grabs attention today. A seductive false “logic” still clings to the ancient image. To people who have never drawn a Scythian-style bow or observed women archers competing in Mongolia, it seems to make sense that womanly breasts might present an encumbrance in archery. But drawing the bowstring back along the cheek or holding the bow out from the body while turning to the side means that breasts are no hindrance and there is no danger of injury to them.

Instead, a real concern is that loose clothing might interfere with the bowstring. Therefore archers wear body-hugging upper garments, like those shown on many Amazons in ancient art. For beginning longbow archers, the most vulnerable area is the inner forearm, which can be struck by the bowstring. Yet the notion of protecting the chest persists in archery. Women—and men too—are often encouraged, even required, to wear chest-guards, even though expert male and female archers find that close-fitting shirts and a forearm guard are the only safety requirements. An analogy exists in modern boxing. Unsubstantiated safety concerns were long used to justify excluding women from boxing. Women won the right to box in the 1970s in the United States but were required to wear an unwieldy plastic chest shield, which caused more cuts and bruises and made the chest a much bigger target. In 2008, medical experts convinced the boxing commission to lift the regulation.”

- Adrienne Mayor, “Breasts: One or Two?” in The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World

230 notes

·

View notes

Text

so last quarter, i took a bioarchaeology class, and in it, we learned some of the methods used to sex a skeleton. we also learned that sexing a pre-pubescent skeleton is virtually impossible. about a month or so ago, i started reA-watching some Bones episodes while working, and now, now i get so so mad whenever brennan goes up to some remains and says something like, "adolescent, maybe uhh, seven, female". i mean i get it, the show needs to have the sex to start the investigation, but can't they find out some other way?? with all the research i'm sure the writers have done for the show, they must know this.

#me#sorry this is meaningless#i'm just complaining because the material i'm using for my thesis often doesn't include sex#which is so annoying#it would be so useful#i must vent my frustrations on something other than my thesis

1 note

·

View note

Text

The fact that everything in archaeology/bioarchaeology is all about the context makes my weird neurodivergent brain very happy! Every bit of information is necessary, and there's always a new thing to learn!

#archaeology#bioarchaeology#anthropology#physical anthropology#bioarchaeology of adolescence#bioarchaeology of childhoood#archaeology of childhood#study#studyblr#phdblr#phdjourney#osteoarchaeology

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Third day being a "just a girl hanging around to enter a PhD program":

I'm studying new adolescent individuals to continue my graduate research, and the ones I'm currently analyzing are from a Bronze Age site in Italy (my favorite time period to work with!!). One of the skeletons belongs to a young woman who presents signs of a possible pregnancy. Although parturition markers are quite tricky to identify and they cannot tell with absolute certainty that a pregnancy occurred, it still amazes me (even after so many years in this field!) that we can hypothesize such an intimate detail about the life of someone who lived so far away in the past.

On a less uplifting note, I feel like my journey into this phd life will be a lonely one. Usually I’m the one motivating my colleagues but I rarely receive back the same energy back. I’m quite solitary and independent, I don’t mind doing my own thing but sometimes I wish I could receive more external support.

#bioarchaeology#anthropology#physical anthropology#archaeology#bioarchaeology of adolescence#bioarchaeology of childhoood#archaeology of childhood#osteoarchaeology#osteology#study#studyblr#phdblr#phdjourney

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have ended up working on three different projects at the same time. Keywords are catch-up growth, teen mums, and stress on the growing bone. My current position in university is terribly precarious and makes me quite uneasy. But my love for this subject is growing, and I can’t help giving in to my unstable life made of books and old bones. My stress levels are way above average, but at least I’m enjoying this ride so far!

Also, I started tutoring students during their practical osteoarchaeology lessons. I LOVE IT! The students were so excited to learn and made brilliant deductions about the individuals they were studying. I hope they keep on with this motivation.

+ Our department also hosts the botanical garden. I often escape there when my coworkers get too annoying.

#archaeology#bioarchaeology#anthropology#physical anthropology#bioarchaeology of adolescence#bioarchaeology of childhoood#studyblr#archaeology of childhood#study#phdblr#phdjourney#phd

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

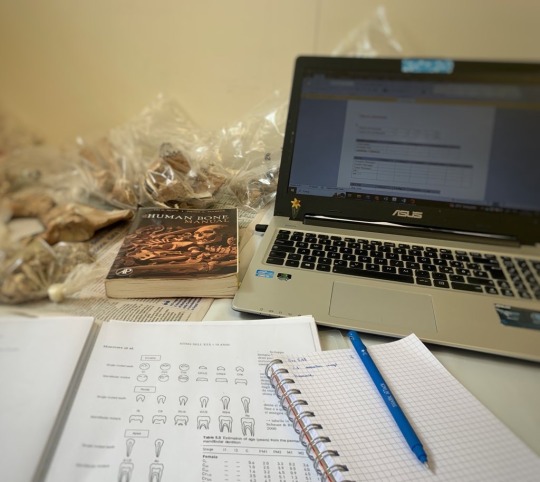

Ordinary day at the anthropology department

For context: this is a tc scan of a mandible of a child. It was done so I could assess their age with more accuracy. In general anthropological practice we use the grade of eruption of the permanent teeth to estimate an age so radioimaging is not necessary but in my case I’m doing something a little more specific and I look at the mineralization of dental roots.

I’m a graduate researcher and I study children and adolescents from archaeological contexts ☺️

#archaeology#bioarchaeology#physical anthropology#anthropology#studyblr#osteoarchaeology#study#archaeology of childhood#bioarchaeology of adolescence#bioarchaeology of childhoood

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today I’m collecting data and working on a poster I’m presenting in September. Summing up a year and a half of nonstop research is quite challenging but I’m excited to share it with just anyone other than my supervisor.

+ our department has some cool fossil reproductions on display, can you recognise any of the animals shown in the picture?

#archaeology#bioarchaeology#anthropology#bioarchaeology of adolescence#physical anthropology#bioarchaeology of childhoood#fossils#palaeoblr#palaeontology#archaeozoology#studyblr#study#on my desk#grad researcher

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last week I took a trip abroad for the first time in five years! I did touristy walks around Antwerp and spent lovely quality time with a dear friend who is now living there (I ate lots of waffles too!).

Today, I went to the library to borrow some books and when I arrived at work I found boxes containing skeletons deposited right by my chair. And this is the Anthropology department for you!!

Now, it's me and my lolita dress against Academia. Time to put on my current obsession (Kælan Mikla = Icelandic post-punk. Very dark and cool, I recommend listening if you're into this genre) and get this manuscript done!

#archaeology#bioarchaeology#anthropology#physical anthropology#bioarchaeology of adolescence#bioarchaeology of childhoood#archaeology of childhood#studyblr#study#osteoarchaeology#phdblr#phdjourney

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

I hate that in the context of bioarchaeology of childhood and adolescence, we must always specify that the individuals we're studying are the non-survivors and therefore cannot be representative of the living population. Like, excuse me, the individuals we study were part of a society, lived in the daily life that we're trying to reconstruct through our job. They may have been the frail part of a population that didn't make it to full adulthood but that doesn't mean those lives have less meaning, even academically speaking.

#bioarchaeology#bioarchaeology of childhoood#bioarchaeology of adolescence#archaeology#physical anthropology#rant

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Archaeology is a sum of human mistakes”

This is a sign we put in our on-site lab during last month excavation. This quote is the result of a particularly hard day and a particularly hard month. I am sharing it on here because this can be read in many ways, my take is that making mistakes is part of the journey and even at the highest levels of education we are never free from it and it’s okay, learning is a process!

#archaeology#bioarchaeology#anthropology#physical anthropology#bioarchaeology of adolescence#bioarchaeology of childhoood#studyblr#study#archaeology of childhood

0 notes

Text

It’s been a long time since I last posted here on Tumblr.

I had a rough start of the year, both personally and academically, but I’ve kept myself quite busy.

Firstly, I visited a new city to study some very cool Bronze Age skeletons. The work itself was very gratifying but I spent a whole week in a basement working in a complete mess, I wasn’t expecting it but archaeology can be like this sometimes. At least I got the opportunity to study kids that were buried with swords (!!!)

Also, I’m studying for a job opportunity that came up. I can’t say much right now but if I get it I would get to work on completely new topics.

I have an enormous amount of things to do and very little energy to keep up with it but I’m definitely trying my best here. Hopefully, spring will be a little bit better!

I know very few people follow my blog but I promise to myself that I will bring more interesting content on here. Maybe something more educational about my job…?

Any ideas? Requests? Suggestions?

#archaeology#bioarchaeology#anthropology#physical anthropology#studyblr#bioarchaeology of childhoood#archaeology of childhood#bioarchaeology of adolescence#study#osteoarchaeology#phdjourney#student life

6 notes

·

View notes