#but even i struggle to afford n95s

Text

Everyone should wear a mask to protect others and that's something I wholeheartedly agree with, but to say people who stopped wearing masks these past couple years eugenicists and lazy is disingenuous. Laziness is not the root of the issue here. The issue is that N95s - the main mask that protects people - are expensive and rare as hell! Stores have just straight up stopped selling them, and people have to spend loads of money to keep others safe. And no, most people can't just stay home - we're living in an economic crisis where people need to work and build community to survive.

Capitalism is, once again, the problem. Absolutely mask up in the best way you can, whether that's buying expensive N95s or even just a few handmade reusable cloth masks. Protect your community and neighbors. But don't blame said neighbors in the process. Focus on supporting endeavors that provide people free masks!

#i'm lucky to be relatively well-off financially#but even i struggle to afford n95s#luckily my local library gives them out for free#but i find myself reusing disposable masks a lot#which i know is not good#wear a mask#emerald coos

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

{out of paprikash} Sorry, guys... HUGE mood drop tonight. Below the cut if you want to know why, but... yeah. I’m hoping that once I start answering asks and things I’ll slowly pull out of it and be up to working on drafts, but I’m not making a lot of promises. I’m just so frustrated and tired. I will at least get the asks people sent in done, that I can promise.

I’ve been on a waiting list to get a vaccine for 8 weeks now. I’m immunocompromised, but apparently not enough for my state to care, so I’m considered to not be in any category that needs the vaccine soon. So I’ve just been waiting. My 70 year-old father just got his second shot, and my 90 year-old grandmother will get her second shot soon, but I haven’t even gotten my first. They’re starting to go out and do more things and enjoy some pre-pandemic niceties, but I’m still holed up in the house like I have been for a year, only going out for doctor’s appointments, to go to the supermarket, or to pick up prescriptions. Being overwhelmingly sad, bored, and hopeless every day just seems to be my new normal now. It hurts to be left out of things they’re doing, but with the meds I’m on, I’m at higher risk to get lots of things, including covid.

What’s really annoying is that my grandmother doesn’t care at all to be careful about not bringing covid home to me and my dad. We told her she couldn’t get a haircut when all the salons were closed, but she wanted one anyway, so she left the house, walked down to someone we didn’t even know, went in this person’s house without a mask, and had her cut her hair. Then came home and was so proud that she did it, throwing it in my face like see I got it done anyway even though you tried to prevent me from doing it. She also then told me the woman wasn’t feeling well and “had a cold or something.” I was livid, and I let her know it. I told her she could kill me if she gave me covid right now. Her response? *shrug* “Oh well.” I was like no, not oh well, take this seriously, wtf?! She then went on about what a nice job the woman did and how happy she was to “get my haircut finally.” I was like “yeah, grandma, I guess that’s worth me dying over.” She laughed. LAUGHED. And she doesn’t even have her second shot yet, and today she told me she went out and talked to some people and pet their dogs. All things we’ve told her she is absolutely not to do. She waits until we’re not home and then goes out and does all the things we’ve told her not to do. Basically she’s told me that I’m not to tell her what to do, and that she’s going to do what she wants because she’s 90 and entitled to do whatever she wants. *throws up hands* I don’t feel safe with her living here, but there’s nothing I can do about it. It’s my dad’s house and his decision, and I can’t afford to move out.

I became eligible for the vaccine a week ago and have been waiting to be contacted and told that I’m allowed to finally make an appointment. Now, when my dad and grandmother were contacted, it was super easy for them. They had their pick of sites and vaccines, and were able to conveniently go to a site that is within walking distance of our house. Welp. I got my email today, and that site was not available. Nor were any sites close by. I’m in the high risk group for the J&J vaccine, so I don’t want that one, and my grandmother and dad got the Pfizer-Biontech one and haven’t had any side effects, so I really want that one. Well... if I want to get that one, the closest place they were letting me make an appointment was 67 miles away. Basically an hour drive. The rest of the sites were maybe 20 or 30 minutes away and were offering the Moderna vaccine, but they were limiting it to local residents only, so I couldn’t even sign up for those. My choices are... to drive two hours round trip, which I can’t really do right now because I have a chronic illness that causes me a lot of pain in my legs, or to continue to just wait and hope for this list of places to change. I don’t even know if it will.

I just kindof lost my shit a little. Had a good cry. My dad only had to wait four weeks for his first shot. My grandmother? Two weeks. From the time they signed up. I’ve been waiting 8 weeks, and I still can’t even go because I’m not being offered the same options they were. Why am I not being given the same opportunities that they were? I would just say well maybe that super close site ran out, but it’s mega-vac site run by the National Guard. It’s huge! They have plenty of vaccine. So wtf. And if you go to their site, it says there are appointments available, yet when you click on the link, all it does is give you a form and then tell you you’re on the same list I’ve already been on for 8 weeks. That’s not what happened for the rest of my family and I’m just feeling very excluded and left behind. My family is starting to put the pandemic behind them and I can’t do the same. They’re moving on without me. I don’t blame them for that, I’m happy they’re vaccinated, but it still doesn’t feel good.

I know I shouldn’t feel this way and it kindof makes me a bad person to complain at all, especially given that there are a lot of people in the world who don’t have access to the vaccine at all, but it’s hard when it’s been a solid year of depression and being in the house (not that I wasn’t depressed before... it’s always been a struggle for me), since my place of work will not even permit me to physically go to work until I’m vaccinated, and the rest of the family is happy and relived that they’re protected and going out and doing things and I’m just sitting at home... waving goodbye... telling them I hope they have a nice day. It hurts. Every day I have to double-mask when I go out, wearing an n95 and then a cloth one over it, because if I get covid I could die. And today in the supermarket I almost passed out because it was a really humid day and I legit couldn’t breathe. But I have to do it. Because no vaccine. I went to pick up food today, because for some reason that’s still my job even though I’m the only one not vaccinated, and the restaurant made me stand right by the door as all these unmasked people walked by. One guy coughed right in my face and I almost had a panic attack right there. And I’m frustrated. And so, so tired of this pandemic.

So... I’m deciding to wait and hope that a closer appointment that I’m eligible for becomes available rather than drive two hours. For now. Maybe at some point I’ll just decide to do the trip and take a lot of meds and frequent breaks while driving and hope for the best, but right now I’m hoping something else opens up soon. If you’ve read this far, I’m really sorry for wasting your time with this rant, but also thank you for caring enough to read it.

#{ out of paprikash } ᵒᵒᶜ#{sorry for the rant}#{i just needed to get that out}#{i got my hopes up so high when I got the email}#{i thought yes finally here we go}#{and then........ crash}#{nope sorry just kidding}

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Residency in the time of corona, Follow the science, 201129

I have been struggling to articulate my thoughts on COVID for a while. I feel like I have a few main questions like A. What does it mean to “follow the science” and what exactly is “evidence-based medicine?” B. How important is COVID? What I wonder is, how much of our efforts in biomedicine should be re-routed to COVID from ongoing problems like HIV, drug addiction, diabetes? C. How should societal inequalities play into our response to COVID? And D. COVID fatigue. I will try to put some of these ideas together.

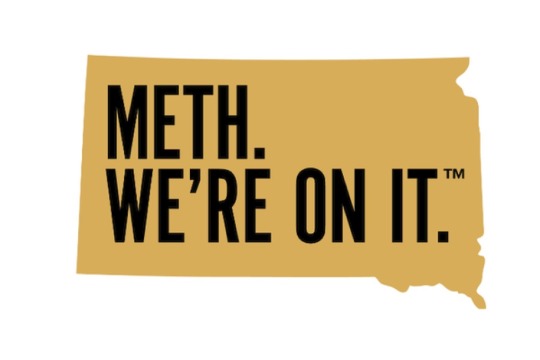

About a year and a half ago I moved to Sioux Falls, South Dakota and I assumed I would live in an anonymous place for a few years. To my surprise, in that year and a half Sioux Falls has made the national news twice. sidenote – Actually now that I think about it there was also this time:

I just googled “meth we’re on it” and I found this and I have to say that I love that someone thought this was such a good idea that it had to be trademarked. Anyways, the first time Sioux Falls was in the news this year was for a COVID superspreading event that happened in a Sioux Falls meat packing plant where a lot of refugees and poor families work. At the time it got a lot of press because it was a concrete example of how the poor were preferentially being killed by COVID. White collar workers with a savings account could afford to stay at home and away from COVID but blue collar workers living paycheck to paycheck had to be out there in the community working. I was worried that this event was just the beginning and it would spread across Sioux Falls. But in fact it didn’t. The outbreak came and went and through the summer COVID was basically a non-issue. In South Dakota we were safe. We didn’t social distance. We never wore masks. And we had no COVID. It gave me a false sense of hope that we were different in South Dakota. Maybe it was the built-in distance of a rural area. Maybe it was the lack of public transportation. Who knows. I didn’t know what it was but I felt like we had dodged a bullet. Turns out I was wrong.

Last month I was on our inpatient team and the hospital is on fire. Obviously I haven’t been a doctor for that long but I’m pretty sure right now is not normal. I think, before last month, I would have been in the camp of people saying that we do not need to be extending excess sympathy to privileged doctors for doing their job but when I was actually in the midst of it was really hard. We had more struggles to send our patients to the ICU because it was so full. We were managing sicker patients with overworked staff. When the hospitals filled up I thought it would hit a plateau but then they started double-rooming patients and then I was going down halls to see patients in rooms I had never been to before. And the patients weren’t only medically complex. I feel like we were ordering more one-to-one babysitters than ever. These are basically staff members that sit in a patient’s room to make sure they behave or at least don’t kill themselves. It’s not an incredibly common occasion to order these one-to-one’s but I swear we had more aggressive and more suicidal patients than I remember seeing. And it’s not even just the extra work or the complex patients that bothers me the most, it’s that there’s this underlying level of stress. It’s keeping up with the constant changes to sick leave policies. It’s those extra couple minutes to put on PPE when I’m already running behind to rounds. It’s when my already quiet voice is further muffled by an N95 and my patients are like what are you even saying. It’s trying to keep up with the latest information when I don’t have the time to know what information to trust. It’s when hospital leadership comes out to tell us that the pandemic is not a big deal. It’s all little things but these are the exact kinds of insidious things that lead to burnout in healthcare professionals. So now Sioux Falls is back in the news for this:

South Dakota is demolishing the hospitalized per capita race. sidenote- My mom told me that South Dakota is even making the news in Japan. My 90 year old grandmother was like wtf is South Dakota doing on the Japan news?? This is probably the first time Japanese people have heard of Sioux Falls. The argument can be made, at least we’re not as bad as New Jersey and New York when they spiked, and certainly that’s not wrong.. but that’s also not right. This probably goes without saying but the size of the hospital infrastructure in South Dakota vs New York City is not the same. When the Sioux Falls hospitals are getting overwhelmed it doesn’t just mean that Sioux Falls suffers. All the complicated patients that typically get transferred in from the surrounding towns are getting backed up into rural community hospitals. I’m trying to get licensed to start moonlighting in one of these rural community hospitals and I can tell you that I would not feel confident taking care of ventilated patients with COVID and PE’s. And sidenote - a couple weeks ago a mask mandate for Sioux Falls got shut down and then approved all in the same week. Everything is happening so fast. I have worries about this mask mandate. I have worries about masks in general because masks has become more than a covering for your face. I do think masks are more or less a good idea and I agree that they probably help prevent COVID but I also think the effect is probably pretty minimal and that the science in support of masks is not exactly a slam dunk. To me the masks thing is representative of a greater problem with this COVID. I know we are supposed to trust the science but I’m just not sure science is made to be used at this sort of pace. Science is cumulative. The way I think about it, science is the kind of thing where one person makes a small discovery, someone else makes another small discovery, then four small discoveries come together to make a medium discovery, but one of those small discoveries turns out not to be reproducible so it takes a while to rethink that medium discovery, and then finally someone in an unrelated field stumbles upon a discovery that gets combined with that medium discovery to create a big discovery like gleevac for CML or reverse transcriptase inhibitors for HIV. If we rush to draw major policy-driving conclusions from one of those small or even medium-level discoveries then we run a major risk of overturning policies, which can get real confusing. I mean think about masks, our public health god Tony Fauci was saying in March that masks are not the end-all and now we are splitting families apart because some people just don’t want to deal with the hassle of wearing a mask. And think of the other aspects of COVID science. We’ve learned that a bunch of stuff doesn’t work (aggressive anti-coagulation, tocilizumab, convalescent plasma), that some stuff actually makes people worse (hydroxychloroquine), and that some stuff that has been shown to work is pretty shaky when attempts have been made to reproduce those findings (decadron, remdesevir). sidenote- should it even be a surprise that steroids may or may not help in a patient with viral ARDS? I sometimes wonder what would have happened if we had just managed these patients as ARDS/sepsis-type patients rather than COVID patients. I think the most unique thing about COVID is its non-effect on kids. That part puzzles me. Anyways, I don’t mean to be a science downer but out of respect for science I just feel we need to be realistic about what it can and cannot do.

See you on the other side,

from ken

0 notes

Text

I didn’t meet Jesus.

I couldn’t get air, I was gasping for air like I had just run a 10k and I could not catch my breath. After 30 minutes we loaded up, our trip to the mountains was over, we were headed back to Nashville from outside of Chattanooga. Between breaths I told Ally to go 90 and we’d be to Franklin in 2 hours, if I needed to go to the hospital I wanted to be close to home. 20 minutes later we were coming into Chattanooga and the struggle to get air had only worsened. By this point I was literally fighting for every breath.

My hands had become tingly as my body was preserving oxygen for vital organs. Pretty soon my fingers were constricted, and I had lost the use of them. My hands were completely numb. The tingly feeling was now creeping up my arms. Before I knew it I could not feel anything up to my elbows. I was fighting it as hard as I could, but nothing was working, no matter how I tried to adjust my breathing, I couldn’t get enough air. There was no way I would make it two hours to Franklin. I found the energy to say, “Ally, find an ER, find and ER now.” Fortunately, we were only about 10 minutes away from Erlanger East Hospital, but I didn’t know if I could make it that long.

My head started tingling, the same thing that I had felt in my fingers, and I knew that this wasn’t good sign. Between breaths told my 15 year old son Levi how much I loved him and that I was proud of him. I told him to take care of his mom and sister. Then I told Sol, my 17 year old daughter, how proud of her I was and that I loved her. Finally, exhausted from the effort, I looked towards Ally, I told her I loved her so much, and then I told her that she was strong and that she would be ok without me. I told her that I was sorry that we hadn’t figured out the happy marriage thing earlier in our marriage. She softly replied, that she loved me too, and that she too was sorry. I couldn’t say anything else. I started to cry which only made breathing worse. Ally told me to stop, that I had to calm down, that I was going to make the situation worse. She was right.

A black curtain began to slowly close over my vision as my oxygen depleted brain was turning off all non-essential systems. I prayed softly outload. I expressed my love to God and asked for forgiveness for my failures. I was at peace. I was going to die. I was surprised that I wasn’t scared and while I was emotional that I was not going to be living more life with the three people I love most in this world, I was okay. I was going to see Jesus.

We finally arrived at the ER, they were expecting us, Ally had called and told them that we were coming and that I was in Acute Respiratory Distress and Shock. When they opened the door to the SUV I spoke a few words to the nurses who received us and they helped me onto a gurney, and then everything went black. That was it.

When I opened my eyes the first thing I saw was a large face shield, behind it goggles and a teal green N95 respirator. There was a flurry of activity around me and someone was yelling at me for my name. There was a massive 18 gauge IV in my arm, a dozen or so electrodes connected to my chest, oxygen on my nose, a blood pressure cuff on my arm, and an oxygen sensor clipped to my finger. I was still breathing hard and when I realized that there was oxygen on my nose I immediately focused on breathing through my nose. I knew that I would come out of this as soon as my body got enough oxygen.

It would take about 45 minutes but slowly but surely my breathing stabilized. I was in a pressure negative room, a small room in the ER with a strong fan pulling out all contaminates from the room, all symptoms pointed to a classic COVID patient. I was alone in this small, isolated room as everyone waited for lab results on the blood they had taken. I tried to raise my head to look around, it was almost impossible, it felt like it weighed 100 pounds. I didn’t get to meet Jesus.

Friday morning I woke up in my hospital room and looked around. Honestly, I was in luxury accommodations. My room was big enough for 3 or 4 beds. The bathroom itself could almost hold a full hospital bed. It was all sparkling clean, electronic state of the art monitors tracked my every breath and heartbeat. The flat screen tv sat in the middle of the meticulously well thought out design of the room. My feelings of thankfulness to have access to this level of treatment and accommodations were overwhelmed with guilt. If my situation had played out in Honduras or Haiti I would most likely be dead now. And I have hundreds of friends, fellow committed and devoted believers, who can’t just “get out” back to the US when times are tough. They have no other options and if they get sick their experience will be dramatically different than mine.

This week I’ve received many videos and pictures from the hospital in Choluteca and other parts of Honduras. If the rooms being full and patients laying on the floor in the hallways wasn’t bad enough, the hospital in Choluteca now has patients laying on the ground on pieces of cardboard, outside of the hospital. And with few options for treatment and a ventilator only being available for a select few the morgues are literally overflowing, with bodies in body bags piling up, not even in refrigeration. And with inadequate protection gear doctors and nurses are quitting throughout the country, not willing to continue risking their lives when they know better than the general public that if they get sick the hospitals cannot do anything for them.

Why do I share this? Because we are a land of people that are actively ripping ourselves apart, whether it’s politics, race, religion or whatever the debate du jour is, we’re ripping ourselves apart. Are the issues we’re debating important, sure they are, but are they more important than human life? Absolutely not. And around the world millions of people can’t even begin to start a debate around the things that we’re literally killing each other over because they don’t have that luxury because they struggle to survive daily, and that was before a Pandemic. The mere fact that we can afford to debate and argue these things speaks to our privilege in this great land, we are truly blessed, but we don’t even realize to what level or what that means. To me it feels like Christs words in Matthew 22:39 have almost completely lost their meaning to us. And these words, per Christ’s own declaration, are the second most important commandment for us to keep, “Love your neighbor as yourself.”

#covid#covid-19#corona#acuterespiratorydistress#shock#facemask#mask#loveyourneighbor#Honduras#haiti#missionlazarus#misionlazaro#missionlazare

0 notes

Text

Reopening the World: Coordinating the international distribution of medical goods

Register at https://mignation.com The Only Social Network for Migrants. #Immigration, #Migration, #Mignation ---

New Post has been published on http://khalilhumam.com/reopening-the-world-coordinating-the-international-distribution-of-medical-goods/

Reopening the World: Coordinating the international distribution of medical goods

By Geoffrey Gertz

Like other countries around the world, the U.S. is beginning to re-open while coronavirus transmission persists in many communities and before a vaccine has been discovered. This suggests demand for key medical goods—including medicines, coronavirus tests, ventilators, and crucial personal protective equipment (PPE) such as N95 masks—will remain high, both as precautionary measures and to respond to localized flare-ups or a possible second wave of the virus. Supply of such goods has and will continue to increase. But even with an aggressive push to increase production, supply is unlikely to be sufficient to meet the 20-fold increase in demand. During the first wave of the coronavirus outbreak, the federal government struggled to get medical goods to the people and places that needed them. It initially left distribution to market mechanisms—sparking price spirals and accusations of gouging by profiteers as state governments and hospital systems bid against one another, desperately seeking supplies. More recently, the government began blocking the export of certain medical goods, cutting off trade flows to countries in need. Looking forward, the U.S. needs to avoid the pitfalls of both the wild west of unfettered markets and the threat of every-country-for-themselves economic nationalism. To reopen while preventing the price spirals, trade restrictions, and shortages that have so far plagued medical goods markets, the U.S. government should cooperate with other countries around the world to better organize and coordinate the procurement and international distribution of key medical goods. By establishing communication channels and coherently planning the demand and supply of such products, governments can build trust in each other and lay the foundation for more effective management of global health.

Calling for global cooperation during a crisis may seem far-fetched, yet history shows that it is precisely during emergencies that the need for cooperation to achieve public goods can spur government action.

FROM MARKET PANDEMONIUM TO ECONOMIC NATIONALISM

Through the early months of the coronavirus pandemic, the U.S. government largely refrained from intervening in markets for medical goods. The result was chaos: governors and hospitals found themselves competing against one another, struggling to evaluate a dizzying array of offers from amateur brokers while bidding up prices to astronomical levels. Ambitious middlemen and profiteers cashed in while doctors and nurses scrambled to make do with what they could find. As economists often note, one virtue of market mechanisms and price signals is to allocate goods where demand is highest. Yet price signals conflate both willingness to pay and ability to pay—and in the current context, allocating COVID-19-related medical goods to those who can best afford it does not necessarily align with public interests. Partially in response to such market failures, more recently the federal government has stepped in— but in ways that are sometimes counterproductive. In early April, the government announced it would restrict exports of certain PPE goods. To be sure, the United States is not alone in taking such actions: in the face of stark shortages and spiraling prices, many governments have attempted to prevent medical goods from leaving their country. Based on data collected by the International Trade Centre, as of May 10, around 95 countries have introduced some form of temporary export restrictions related to COVID-19. Though these limits may boost domestic supply, they simply shift the costs of supply shortages on to other countries; and as the escalating number of countries implementing such restrictions suggests, they risk spiraling protectionism that leaves everyone worse off. Thankfully, governments have begun to correct some of their earlier missteps. The European Union, which was one of the first to impose an export licensing regime, has since revised its policy to limit the number of goods facing restrictions, include further humanitarian exceptions, and ensure transparency of all licensing decisions. Similarly, the United States has eased some of its licensing restrictions, allowing for continued exports to Canada and Mexico and for exports donated by nonprofit agencies.

COOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT OF MEDICAL SUPPLY CHAINS

While these corrections are welcome, we are still far from what is needed: international coordination to promote a more orderly distribution of medical goods. Calling for global cooperation during a crisis may seem far-fetched, yet history shows that it is precisely during emergencies that the need for cooperation to achieve public goods can spur government action. For instance, during World War I, Western Allies initially found themselves bidding against one another on crucial agricultural commodities, namely wheat. Just as is the case with medical goods today, the result was spiraling prices and further shortages. In the face of this challenge, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy came together in 1916 to found the Wheat Executive, a centralized body that coordinated all wheat purchases for the three countries. This cooperation expanded the following year with the formation of the Allied Maritime Transport Council, which brought together the U.S., UK, France, and Italy to oversee the allotment of shipping tonnage to ensure transport capacity was available where it was most needed, rather than relying on decentralized market distributions. These examples show how, in the face of politically salient shortages, government leaders can strike creative agreements to avoid both the tyranny of markets and beggarthy-neighbor economic nationalism. Similar efforts are needed today. Coordination of procurement is essential for the world’s poorest countries, which otherwise will be battered by either a market distribution system (as they will be outbid by richer countries) or an economic nationalist approach (as they depend on imports for meeting domestic medical supply needs). But it is also squarely in the United States’ more narrowly defined national interest. Given existing chaos, price spikes, and shortages in the U.S. medical goods market, the American healthcare system would directly benefit from a more orderly and coordinated distribution system. Greater coordination at the international level also would complement greater coordination at the domestic level, as the House of Representatives is currently pushing for. Similarly, the fact that the U.S. imports five times more PPE than it exports underlines that the U.S. stands to lose out overall if every country were to block medical trade. Moreover, leading a coordinated international response to shortages in COVID-19-related medical goods could help restore America’s international reputation, which has been marred by accusations of “piracy” in seeking to amass PPE. In a recent survey of American foreign policy experts, only 3 percent of respondents rated U.S. leadership in coordinating the international response to COVID-19 as either somewhat or very effective, with over 80 percent rating the response as “not effective at all.” Facilitating a coordinated distribution system could begin to recast such perceptions, and simultaneously help counter China’s “mask diplomacy” efforts. What might such a coordinated program look like in practice? Ideally, governments would enter a cooperative arrangement to oversee the distribution of PPE and other medical goods, minimizing any hoarding and allocating goods to the people and places where they’re most needed. Crucially, this could include pooled procurement: rather than competing against one another and bidding up prices, governments would jointly purchase needed medical goods, taking advantage of their buying power to negotiate fair prices. Pooled procurement can also allow buyers to commit to large future purchases, based on their combined forecast demand, incentivizing the investments needed to increase supply. Similar pooled procurement mechanisms have been used for years in acquiring pharmaceutical products, particularly for developing countries; there are certainly lessons from these experiences that could apply to purchases of PPE today. Achieving such levels of cooperation can be difficult, however, particularly given low levels of trust between national governments at present. Indeed, it was a full two years into the First World War before the Wheat Executive was created, which suggests developing such mechanisms can take time. Thus, if governments are unable or unwilling to enter into an arrangement for coordinating the distribution of COVID-19-related medical goods, a possible intermediate step is to improve information sharing and transparency in policymaking. Simply put, governments should inform one another of their supply and demand for specific medical goods, their purchasing plans, and especially any trade policies or export restrictions that will influence global markets. The Agriculture Market Information System (AMIS), created by the G-20 in the wake of food price spikes in 2007–08 and 2010, provides a potential model. AMIS is an information clearing house where governments share market and policy guidance for key agricultural crops and a forum for informal coordination among policymakers, particularly during times of crisis. A similar mechanism for sharing information and discussing policy developments for COVID-19- related medical goods could improve outcomes even without governments ceding any decision–making power to a cooperative body.

PREPARING FOR A VACCINE

There is a pressing immediate need for better coordination of existing COVID-19-related medical goods. Looming on the horizon, however, is an even more challenging international distribution problem: allocating doses for a coronavirus vaccine, once one is discovered. Competition for the vaccine will undoubtedly be stark, and without coordination rival bids will send prices skyrocketing. Efforts today to build trust and establish communication channels in distribution of PPE and other medical goods will lay the groundwork for future cooperation on a potential vaccine. Just as during WWI efforts to coordinate wheat distribution led to the broader program on coordinated shipping, mechanisms developed now can potentially evolve into a system for allocating vaccines in the future.

0 notes

Text

Republican Convention, Day 3: Revisionist History

In accepting the Republican Party nomination Wednesday night, Vice President Mike Pence accurately recounted the history of Baltimore’s Fort McHenry, and how a failed British bombardment in 1814 helped inspire Francis Scott Key to write “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Pence’s claims about the Trump administration as well as his attacks on Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden, on the other hand, were sometimes misleading, incomplete or wrong.

As the number of Americans who have lost their lives to COVID-19 neared 180,000, he spent part of his speech recasting the Trump administration’s handling of the coronavirus response, offering sympathy to “the families who have lost loved ones and have family members still struggling with serious illness” and saluting the “doctors, nurses, first responders, factory workers, truckers and everyday Americans, who put the health and safety of their neighbors first.” He optimistically reported that the U.S. is “on track to have the world’s first safe, effective coronavirus vaccine by the end of this year.” His live audience was mostly unmasked.

Our partners at PolitiFact did a wide-ranging fact check on Pence’s complete speech. Here are the highlights related to the administration’s COVID-19 response:

“President Trump marshaled the full resources of our federal government [to deal with the coronavirus] from the outset. He directed us to forge a seamless partnership with governors across America in both political parties.”

Revisionist history. After declaring a national emergency over the health crisis on March 13, Trump directed governors to order their own ventilators, respirators and supplies, saying the federal government is “not a shipping clerk.” Governors say the disjointed response left states bidding against one another and the federal government for access to critical equipment.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo said it was akin to competing on eBay with all the other states plus the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan, a Republican, pleaded for better coordination to ensure that supplies were distributed based on need.

As late as July, some governors were calling on the feds for help and not getting what they needed. There were shortages of testing supplies, as well as personal protection gear. Washington state asked for 4.2 million N95 face masks. It received a bit under 500,000. It asked for about 300,000 surgical gowns. It got about 160,000.

“Before the first case of the coronavirus spread within the United States, the president took unprecedented action and suspended all travel from China.”

Pence’s timeline is wrong, and Trump didn’t ban “all” travel from China; there were exemptions.

Here’s the correct timeline:

Jan. 21: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the first U.S. case of the new coronavirus, a patient in Washington state who had traveled from Wuhan, China.

Jan. 30: The CDC confirmed the first instance of person-to-person spread of the new coronavirus in the United States. It involved a couple in Illinois, one spouse who had traveled to Wuhan and one who had not traveled.

Jan. 31: The Trump administration announced a ban on travelers from China, exempting a number of categories of people, including U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents. It took effect Feb. 2. Trump’s proclamation acknowledged that the virus “has spread between two people in the United States, representing the first instance of person-to-person transmission of the virus within the United States.”

According to The New York Times, about 40,000 people traveled from China to the United States in the two months after Trump announced travel restrictions, and 60% of people on direct flights from China were not U.S. citizens.

“As we speak, we’re developing a growing number of treatments, known as therapeutics, including convalescent plasma, that are saving lives all across the country.”

This requires context. Days before Pence’s speech, the Food and Drug Administration authorized the use of convalescent plasma for the treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients. This treatment involves isolating COVID-19 antibodies from the plasma of people who have recently recovered from the virus and injecting the antibodies into patients in the early stages of the illness.

Although the Trump administration has said this treatment shows encouraging early findings, the data they shared was based on a Mayo Clinic preliminary analysis that has not been peer-reviewed. Clinicians and researchers have urged caution, maintaining that more research is necessary before a survival benefit is proven. They also question the timing of the authorization — which came on the eve of the Republican convention.

Before Pence Took the Mic

Throughout the evening, speakers referred to the novel coronavirus as “the China virus” or something the “Chinese communist regime unleashed on the world.” Kellyanne Conway, a former special adviser to the president, commended Trump for “taking unprecedented action to combat this nation’s drug crisis.” Our PolitiFact partners fact-checked a range of these statements. Here’s one related to health policy:

“I can tell you that this president stands by Americans with preexisting conditions.” — Kayleigh McEnany, press secretary

McEnany was sharing her personal story of having a preventive mastectomy to minimize her risk for breast cancer, which was prevalent in her family. Trump called to see how she felt after her surgery and, she said, has since continued to be a source of support.

However, the support he provided her has not translated into supporting legal protections for people who have preexisting conditions from being excluded from health plans or charged higher rates. In fact, we rated a claim by Trump in which he said he was the person who saved preexisting conditions as Pants on Fire. He got a False rating for saying he would protect those with preexisting conditions.

The Affordable Care Act, which was signed into law by President Barack Obama in 2010, put in place these protections. Trump has supported overturning the ACA. In 2017, Trump supported congressional efforts to repeal the ACA. The Trump administration is now backing the efforts to overturn the ACA via a court case. He has also expanded short-term health plans that don’t have to comply with the ACA.

Jon Greenberg, Louis Jacobson, Samantha Putterman, Amy Sherman, Paul Specht, Miriam Valverde and KHN reporter Victoria Knight contributed to this report. All photos courtesy of the Associated Press.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Republican Convention, Day 3: Revisionist History published first on https://nootropicspowdersupplier.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

Republican Convention, Day 3: Revisionist History

In accepting the Republican Party nomination Wednesday night, Vice President Mike Pence accurately recounted the history of Baltimore’s Fort McHenry, and how a failed British bombardment in 1814 helped inspire Francis Scott Key to write “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Pence’s claims about the Trump administration as well as his attacks on Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden, on the other hand, were sometimes misleading, incomplete or wrong.

As the number of Americans who have lost their lives to COVID-19 neared 180,000, he spent part of his speech recasting the Trump administration’s handling of the coronavirus response, offering sympathy to “the families who have lost loved ones and have family members still struggling with serious illness” and saluting the “doctors, nurses, first responders, factory workers, truckers and everyday Americans, who put the health and safety of their neighbors first.” He optimistically reported that the U.S. is “on track to have the world’s first safe, effective coronavirus vaccine by the end of this year.” His live audience was mostly unmasked.

Our partners at PolitiFact did a wide-ranging fact check on Pence’s complete speech. Here are the highlights related to the administration’s COVID-19 response:

“President Trump marshaled the full resources of our federal government [to deal with the coronavirus] from the outset. He directed us to forge a seamless partnership with governors across America in both political parties.”

Revisionist history. After declaring a national emergency over the health crisis on March 13, Trump directed governors to order their own ventilators, respirators and supplies, saying the federal government is “not a shipping clerk.” Governors say the disjointed response left states bidding against one another and the federal government for access to critical equipment.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo said it was akin to competing on eBay with all the other states plus the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan, a Republican, pleaded for better coordination to ensure that supplies were distributed based on need.

As late as July, some governors were calling on the feds for help and not getting what they needed. There were shortages of testing supplies, as well as personal protection gear. Washington state asked for 4.2 million N95 face masks. It received a bit under 500,000. It asked for about 300,000 surgical gowns. It got about 160,000.

“Before the first case of the coronavirus spread within the United States, the president took unprecedented action and suspended all travel from China.”

Pence’s timeline is wrong, and Trump didn’t ban “all” travel from China; there were exemptions.

Here’s the correct timeline:

Jan. 21: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the first U.S. case of the new coronavirus, a patient in Washington state who had traveled from Wuhan, China.

Jan. 30: The CDC confirmed the first instance of person-to-person spread of the new coronavirus in the United States. It involved a couple in Illinois, one spouse who had traveled to Wuhan and one who had not traveled.

Jan. 31: The Trump administration announced a ban on travelers from China, exempting a number of categories of people, including U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents. It took effect Feb. 2. Trump’s proclamation acknowledged that the virus “has spread between two people in the United States, representing the first instance of person-to-person transmission of the virus within the United States.”

According to The New York Times, about 40,000 people traveled from China to the United States in the two months after Trump announced travel restrictions, and 60% of people on direct flights from China were not U.S. citizens.

“As we speak, we’re developing a growing number of treatments, known as therapeutics, including convalescent plasma, that are saving lives all across the country.”

This requires context. Days before Pence’s speech, the Food and Drug Administration authorized the use of convalescent plasma for the treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients. This treatment involves isolating COVID-19 antibodies from the plasma of people who have recently recovered from the virus and injecting the antibodies into patients in the early stages of the illness.

Although the Trump administration has said this treatment shows encouraging early findings, the data they shared was based on a Mayo Clinic preliminary analysis that has not been peer-reviewed. Clinicians and researchers have urged caution, maintaining that more research is necessary before a survival benefit is proven. They also question the timing of the authorization — which came on the eve of the Republican convention.

Before Pence Took the Mic

Throughout the evening, speakers referred to the novel coronavirus as “the China virus” or something the “Chinese communist regime unleashed on the world.” Kellyanne Conway, a former special adviser to the president, commended Trump for “taking unprecedented action to combat this nation’s drug crisis.” Our PolitiFact partners fact-checked a range of these statements. Here’s one related to health policy:

“I can tell you that this president stands by Americans with preexisting conditions.” — Kayleigh McEnany, press secretary

McEnany was sharing her personal story of having a preventive mastectomy to minimize her risk for breast cancer, which was prevalent in her family. Trump called to see how she felt after her surgery and, she said, has since continued to be a source of support.

However, the support he provided her has not translated into supporting legal protections for people who have preexisting conditions from being excluded from health plans or charged higher rates. In fact, we rated a claim by Trump in which he said he was the person who saved preexisting conditions as Pants on Fire. He got a False rating for saying he would protect those with preexisting conditions.

The Affordable Care Act, which was signed into law by President Barack Obama in 2010, put in place these protections. Trump has supported overturning the ACA. In 2017, Trump supported congressional efforts to repeal the ACA. The Trump administration is now backing the efforts to overturn the ACA via a court case. He has also expanded short-term health plans that don’t have to comply with the ACA.

Jon Greenberg, Louis Jacobson, Samantha Putterman, Amy Sherman, Paul Specht, Miriam Valverde and KHN reporter Victoria Knight contributed to this report. All photos courtesy of the Associated Press.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

from Updates By Dina https://khn.org/news/republican-convention-day-3-revisionist-history/

0 notes

Text

Republican Convention, Day 3: Revisionist History

In accepting the Republican Party nomination Wednesday night, Vice President Mike Pence accurately recounted the history of Baltimore’s Fort McHenry, and how a failed British bombardment in 1814 helped inspire Francis Scott Key to write “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Pence’s claims about the Trump administration as well as his attacks on Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden, on the other hand, were sometimes misleading, incomplete or wrong.

As the number of Americans who have lost their lives to COVID-19 neared 180,000, he spent part of his speech recasting the Trump administration’s handling of the coronavirus response, offering sympathy to “the families who have lost loved ones and have family members still struggling with serious illness” and saluting the “doctors, nurses, first responders, factory workers, truckers and everyday Americans, who put the health and safety of their neighbors first.” He optimistically reported that the U.S. is “on track to have the world’s first safe, effective coronavirus vaccine by the end of this year.” His live audience was mostly unmasked.

Our partners at PolitiFact did a wide-ranging fact check on Pence’s complete speech. Here are the highlights related to the administration’s COVID-19 response:

“President Trump marshaled the full resources of our federal government [to deal with the coronavirus] from the outset. He directed us to forge a seamless partnership with governors across America in both political parties.”

Revisionist history. After declaring a national emergency over the health crisis on March 13, Trump directed governors to order their own ventilators, respirators and supplies, saying the federal government is “not a shipping clerk.” Governors say the disjointed response left states bidding against one another and the federal government for access to critical equipment.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo said it was akin to competing on eBay with all the other states plus the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan, a Republican, pleaded for better coordination to ensure that supplies were distributed based on need.

As late as July, some governors were calling on the feds for help and not getting what they needed. There were shortages of testing supplies, as well as personal protection gear. Washington state asked for 4.2 million N95 face masks. It received a bit under 500,000. It asked for about 300,000 surgical gowns. It got about 160,000.

“Before the first case of the coronavirus spread within the United States, the president took unprecedented action and suspended all travel from China.”

Pence’s timeline is wrong, and Trump didn’t ban “all” travel from China; there were exemptions.

Here’s the correct timeline:

Jan. 21: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the first U.S. case of the new coronavirus, a patient in Washington state who had traveled from Wuhan, China.

Jan. 30: The CDC confirmed the first instance of person-to-person spread of the new coronavirus in the United States. It involved a couple in Illinois, one spouse who had traveled to Wuhan and one who had not traveled.

Jan. 31: The Trump administration announced a ban on travelers from China, exempting a number of categories of people, including U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents. It took effect Feb. 2. Trump’s proclamation acknowledged that the virus “has spread between two people in the United States, representing the first instance of person-to-person transmission of the virus within the United States.”

According to The New York Times, about 40,000 people traveled from China to the United States in the two months after Trump announced travel restrictions, and 60% of people on direct flights from China were not U.S. citizens.

“As we speak, we’re developing a growing number of treatments, known as therapeutics, including convalescent plasma, that are saving lives all across the country.”

This requires context. Days before Pence’s speech, the Food and Drug Administration authorized the use of convalescent plasma for the treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients. This treatment involves isolating COVID-19 antibodies from the plasma of people who have recently recovered from the virus and injecting the antibodies into patients in the early stages of the illness.

Although the Trump administration has said this treatment shows encouraging early findings, the data they shared was based on a Mayo Clinic preliminary analysis that has not been peer-reviewed. Clinicians and researchers have urged caution, maintaining that more research is necessary before a survival benefit is proven. They also question the timing of the authorization — which came on the eve of the Republican convention.

Before Pence Took the Mic

Throughout the evening, speakers referred to the novel coronavirus as “the China virus” or something the “Chinese communist regime unleashed on the world.” Kellyanne Conway, a former special adviser to the president, commended Trump for “taking unprecedented action to combat this nation’s drug crisis.” Our PolitiFact partners fact-checked a range of these statements. Here’s one related to health policy:

“I can tell you that this president stands by Americans with preexisting conditions.” — Kayleigh McEnany, press secretary

McEnany was sharing her personal story of having a preventive mastectomy to minimize her risk for breast cancer, which was prevalent in her family. Trump called to see how she felt after her surgery and, she said, has since continued to be a source of support.

However, the support he provided her has not translated into supporting legal protections for people who have preexisting conditions from being excluded from health plans or charged higher rates. In fact, we rated a claim by Trump in which he said he was the person who saved preexisting conditions as Pants on Fire. He got a False rating for saying he would protect those with preexisting conditions.

The Affordable Care Act, which was signed into law by President Barack Obama in 2010, put in place these protections. Trump has supported overturning the ACA. In 2017, Trump supported congressional efforts to repeal the ACA. The Trump administration is now backing the efforts to overturn the ACA via a court case. He has also expanded short-term health plans that don’t have to comply with the ACA.

Jon Greenberg, Louis Jacobson, Samantha Putterman, Amy Sherman, Paul Specht, Miriam Valverde and KHN reporter Victoria Knight contributed to this report. All photos courtesy of the Associated Press.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Republican Convention, Day 3: Revisionist History published first on https://smartdrinkingweb.weebly.com/

0 notes

Text

Ever more disconcerting news and notes from federal prisons' struggle with COVID

It is encouraging that the BOP's COVID-19 Update page, as of midday April 19, is reporting that in the last four weeks "the BOP has placed an additional 1,279 inmates on home confinement." But that is the only encouraging news I could find about the federal prison system this weekend amidst a whole of worrisome headlines and stories:

"Federal prisons confirm first staff death linked to coronavirus"

"Coronavirus cases rising at Chicago’s federal high-rise jail"

"'It was chaos': Former Butner prison inmate describes life inside a coronavirus hot zone"

"‘People are scared.’ Inside a federal prison in N.J. amid the coronavirus outbreak"

"Correctional officers file complaint about coronavirus at federal prison in Tallahassee"

"Judge grills federal prisons lawyer on lack of coronavirus tests at Ohio facility in wake of Trump’s claim that ‘anybody’ can get tested"

"Tens of thousands of inmates unlawfully denied home confinement as pandemic rages: Prisoner advocates"

"‘Something Is Going to Explode’: When Coronavirus Strikes a Prison"

I am tempted to call all of these pieces "must-reads," but I would especially encourage everyone to make the time to review the last piece above. It is a lengthy piece from the New York Times described as an "oral history of the first fatal outbreak in the federal prison system, in Oakdale, La." Much of the reporting is both terrifying and saddening, and here is just a small sample:

Don Cain, inmate at F.C.I. Oakdale I, via email: I will tell you how I heard the virus got in. I was told that a staff member from education bragged about going to New York City. The first death of an inmate was a guy who was in contact with that staff member. I heard that staff member was supposedly in critical condition in the hospital on a ventilator.

Wife of an F.C.C. Oakdale correctional officer, via Facebook Messenger: There’s also a rumor saying an inmate came off the bus as a new intake, and he brought it in.

Mayor Paul: As of last week [the week of March 30], they were still bringing inmates in from other facilities. It took them about a week to stop those buses. There was a lot of the ball being passed around with, “It’s not my responsibility, it’s the marshals’ responsibility, it’s not our responsibility, it’s somebody else’s.” Well, whose responsibility is it to stop this? I mean, I love the B.O.P. being here and everything, but you think you would have taken some precaution 10 or 14 days earlier to be halfway ready for this thing, especially when you got about 2,000 inmates and about 500 employees.

Correctional Officer 2: I know there was a conversation with the warden. It was myself and one of the case managers that I used to work with — who tested positive, by the way, he’s been out for a week, week and a half — he questioned the warden and said, “What do you think about this coronavirus, do you think we’re going to have a problem?” And he said: “Oh, no, because we live in the South, and it’s warm here. We won’t have any problems.” That was his exact words. Nobody gave us new direction on what we should be doing, how we should be preparing, what to look for, anything....

Ronald Morris [correctional officer, president of the American Federation of Government Employees Local 1007]: You got the director of the B.O.P. saying they’ve been preparing since January, and they have a national stockpile of supplies. Well, where the hell are those supplies? Why can’t we get some? They did send us some national-stockpile N95 masks. Want to know how many? Two hundred! Two hundred! They couldn’t afford to give us any more. They know that we’re just the first institution that’s going to be dealing with this, so they need to hold it to ration it out to other institutions because they know their national stockpile is insufficient to begin with.

Heidi Burakiewicz, lead attorney on the federal class-action lawsuit: What I am constantly hearing from workers at Oakdale is that they’re looking for guidance, and they’re getting no guidance or contradictory guidance, or it’s constantly changing. I’m outraged when I hear people tell me: “I rode in a van with a sick inmate, and I asked for a mask, and they said: No, I didn’t need it.” Or: “I sat in a room in the hospital with a sick inmate, and I didn’t even have a mask on.” Or: “It was only a surgical mask.” That makes me angry. That was preventable. Somebody in this agency needs to take responsibility and start protecting these people.

from RSSMix.com Mix ID 8247011 https://sentencing.typepad.com/sentencing_law_and_policy/2020/04/ever-more-disconcerting-news-and-notes-from-federal-prisons-struggle-with-covid.html

via http://www.rssmix.com/

0 notes

Text

Photojournalists Struggle Through the Pandemic, With Masks and Long Lenses

March was shaping up to be a good month for Brian Bowen Smith, a photographer in Los Angeles who has worked for Vogue and GQ. He had five big jobs lined up, including shoots for two Netflix posters. All five were canceled because of the coronavirus pandemic.“There is no work whatsoever,” he said. “It’s kind of scary, actually.”To fill his newly free hours, Mr. Bowen Smith drove to Joshua Tree National Park and trained his camera on the barren landscape. It was a long way from the work that usually pays his bills. In recent years, when he is not photographing Christian Bale, Miley Cyrus and Issa Rae for major magazines, Mr. Bowen Smith has shot ad campaigns for Marc Jacobs and other fashion companies.Now he is telling himself that everything will be OK. “A lot of stuff can be done remotely,” he said. “And maybe that’s going to be our future. Everyone wears masks.”As practitioners of a craft that requires long hours of getting up close and personal with their subjects, photographers have been affected by social distancing restrictions perhaps more than other media workers.“Photographers can’t do what reporters can do — they can’t be on the phone,” said María Salazar Ferro, emergencies director of the Committee to Protect Journalists. “They have to be very close to the action.”Josh Ritchie, a freelance photographer in Florida, estimated that he lost $10,000 in recent weeks because of canceled assignments. To scrounge up money, his attorney has been scouring the web for illegal use of his images.“At night, I’m binge-watching ‘Tiger King’ and having mini panic attacks,” Mr. Ritchie said.Some photojournalists, like Gary He, have gone in search of images particular to a unique moment. One of Mr. He’s photographs, taken last month for the food website Eater, captured an unsettling scene that would have been unremarkable before the spread of the virus: Dozens of people, including delivery workers, crowded on a Manhattan sidewalk as they awaited pickup orders from the restaurant Carbone.“I did a lot more shooting from across the street than I normally would have,” Mr. He said in a text message. And that meant a change in gear. “I use a midrange zoom for most of my work,” he added, “and I’ve been using the longer end of the lens a little bit more these days, to get me a few feet further away from my subjects, mostly for their safety and comfort.”For an Eater shoot last week focused on New York City restaurant workers, Mr. He moved in close, wearing a mask, to take intimate portraits.Some photographers have come down with the virus. Mark Kauzlarich, a freelance photojournalist and commercial photographer whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic and Vanity Fair, said he got very sick last month. Doctors told him it was Covid-19, although he was not tested.“I had said very openly I was sure I was going to get sick,” he said. “We have to be in the field. There’s no way to completely mitigate.”Mr. Kauzlarich, who is on the mend, sounded as if he would not change his approach. “To be a good journalist,” he said, “you can’t be 40 feet away.”Anthony Causi, a staff sports photographer for The New York Post, died of Covid-19, the paper announced on Sunday. A spokeswoman said The Post did not know how Mr. Causi had contracted the disease.The pandemic may be the biggest news story of a generation and, while taking precautions, many editors have sought to get images that show it. On March 10, Radhika Jones, the editor in chief of Vanity Fair, commissioned Alex Majoli to photograph his hard-hit home country, Italy. Vanity Fair published his photo essay on Sicily two weeks later.Ms. Jones said that Mr. Majoli’s experience, which has included stints in Kosovo, Afghanistan and Iraq, made her confident that he would take care of himself.“There is something that is so powerful about an image,” Ms. Jones said. “It doesn’t require translation. We made these pictures in Italy, and in certain ways they’re specific to that experience and even specific to this photographer as an Italian. But they’re also about humanity, and they are universal.”Caitlin Ochs, a freelance photojournalist in Brooklyn, captured images of daily life in the borough amid the outbreak for a Reuters project. Before another assignment, for The Wall Street Journal, an editor at the paper provided her with a Ziploc bag containing N95 masks, gloves and hand sanitizer.Her daily disinfecting routine, informed by an emergency room nurse whom she photographed, can take more than an hour. At the end of a day’s work, she puts on new gloves and wipes down her equipment — cameras, lenses, lens caps, cables — with a 70-percent isopropyl alcohol solution. She also sprays the floor, light switches and faucets with a bleach solution. Before she showers, she stuffs her clothes into a garbage bag to wash later.“Sometimes all this feels crazy, like I’m turning into a hypochondriac,” Ms. Ochs said in an email. “But I’m trying to work from the side of being overly cautious.”Compounding the challenge is the fact that staff jobs for photographers are hard to come by, and many work freelance. The Juntos Photo Coop, made up of four photojournalists in Arizona, published an open letter arguing that the coronavirus crisis had exposed inequitable working conditions for freelance photographers. The group demanded that media organizations provide photographers with protective gear, mental health check-ins and emergency health insurance.“We’re finding out that the most vulnerable people in our industry are the ones without health insurance, who can’t pay rent, who can’t afford to quarantine,” said Caitlin O’Hara, a Coop member. “We’re going to lose all these diverse voices in our industry if only the people who can afford to quarantine can keep working.”Despite the hazards, many photojournalists are driven by a need to record what the world looks like at a dramatic time.“This kind of story is why we all became journalists, no?” Mr. He said. “The pandemic is historic and, especially because of the social distancing, with everyone indoors, there’s a real need for trained storytellers to inform readers about what’s really going on out there.”He added, “I’d do the work for free if I had to.”

Read the full article

#1augustnews#247news#5g570newspaper#660closings#702news#8paradesouth#911fox#abc90seconds#adamuzialkodaily#atoactivitystatement#atobenchmarks#atocodes#atocontact#atoportal#atoportaltaxreturn#attnews#bbnews#bbcnews#bbcpresenters#bigcrossword#bigmoney#bigwxiaomi#bloomberg8001zürich#bmbargainsnews#business#business0balancetransfer#business0062#business0062conestoga#business02#business0450pastpapers

0 notes

Text

Coronavirus patient’s last words: ‘Who’s going to pay for it?’

Moments before being intubated and put on a ventilator, one of Derrick Smith’s coronavirus patients asked, “Who’s going to pay for it?”

It’s “profoundly sad that people are worrying about their finances during even possibly their dying moments,” Smith, 33, told Business Insider.

As a nurse anesthetist at a New York City hospital, Smith has been thrust into a “critical-care role” that’s rife with shortages in personal protective equipment, long work hours, and worries about contagion.

Smith said he was disappointed by government containment measures, describing a failure to “protect and uphold its citizens.”

Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

In Derrick Smith’s view, the coronavirus has turned the United States healthcare system’s pockmarks into garish scars.

In a widely shared Facebook post on Friday, he described a COVID-19 patient’s last words: “Who’s going to pay for it?”

On the verge of being intubated and put on a ventilator, the person “gasped out” the question to their medical team “between labored breaths” before calling their spouse for likely the last time, “as many patients do not recover once tubed,” Smith wrote.

Smith, a certified registered nurse anesthetist at a New York City hospital, whose name he asked be withheld, wrote that “this situation is by far the worst thing I’ve witnessed in my collective 12 years of critical care & anesthesia,” adding, “This country is truly a failed state, and it’s so sickening to witness firsthand, more blatantly than ever.”

Reflecting on the experience, Smith told Business Insider that it’s “profoundly sad that people are worrying about their finances during even possibly their dying moments.” He declined to share more information about the patient, citing privacy laws.

People struggled to grasp the full scope of the coronavirus outbreak while the government tried to downplay it

Smith, 33, recalled first hearing about the coronavirus in January as it raced across Wuhan, China, acknowledging that “it was hard to ascertain the severity of it back then.”

The US reported its first case on January 21. A day later, President Donald Trump told CNBC’s Joe Kernen that he was “not at all” worried.

“It’s one person coming in from China, and we have it under control,” Trump said. “It’s going to be just fine.”

Given that the federal government “didn’t appear to take it very seriously” and was even comparing the disease to the flu to downplay it, Smith said it was only in late February that he began to fully realize the devastation caused by the coronavirus.

He described being instantly worried about the impact that “any sort of viral, contagious pandemic” that progresses quickly would have on the US’s “already fragile healthcare system.”

And what an impact it’s had.

The US has the largest recorded COVID-19 outbreak, with nearly 400,000 confirmed cases and over 12,900 deaths as of Wednesday. New York is the hardest-hit state, with more than 140,300 cases and over 4,000 deaths. Hospitals are overrun, morgues are filled to capacity, and medical workers, who lack sufficient personal protective equipment, are succumbing to the illness themselves.

The Jacob K. Javits Convention Center has been transformed into a 2,500-bed field hospital to deal with the influx of coronavirus patients.

John Lamparski/Getty

The coronavirus has reshaped Smith’s medical work. COVID-19 patients have flooded the various medical facilities where he works, except for a surgical center that is “no longer functioning” because it focuses on elective procedures, which are now scarce.

At the hospital too, his role has morphed. Before the pandemic, Smith’s work was more predictable.

He described his routine as “initially meeting the patient, doing a full interview and physical assessment, taking them to the procedure area, sedating or inducing them for general anesthesia, and then taking care of them up until the post-operative period.”

Since the coronavirus hit New York, however, elective surgeries have been nixed, so Smith has found himself in “more of a critical-care role” that involves working in the intensive care unit or responding to all sorts of emergencies throughout the hospital.

‘I reused the same N95 mask throughout my entire shift’

No two days or cases are alike, Smith said.

“You have some people that come in who are in absolute respiratory distress that need to be intubated relatively soon,” he said. “Or you have someone who’s just very, very ill with classic flu symptoms and upper respiratory problems and don’t quite need to be intubated yet but definitely needs hospitalization, fluids, or antibiotics for pneumonia.”

Coming off a 12-hour shift during which he had only one N95 respirator mask, Smith said that the hospital’s PPE supply had improved but that there was still plenty more to be done to safeguard medical workers and staff.

“I reused the same N95 mask throughout my entire shift, just being careful not to remove it frequently,” he said. This conservation of PPE marks a dramatic shift from “pre-pandemic” times, Smith added, when N95s were the single-use masks they’re designed to be.

Smith said he also expects his team’s shifts to get longer as the hospital is “admitting more and more patients,” increasing their workload.

A hearse backs into a refrigerated truck to pick up bodies outside the Brooklyn Hospital on April 1.

ANGELA WEISS/AFP via Getty Images

Asked if he and his colleagues were worried about contracting the coronavirus, Smith simply replied, “Yes.”

The coronavirus affects people in different ways — some are asymptomatic carriers, while others have such severe symptoms that they require intubation in the ICU, Smith explained.

So Smith, like his friends and coworkers, is “just trying to stay as healthy as possible with diet, home routines, exercise, and adequate sleep to boost” his immunity so he can ward off a severe reaction if he does catch the virus, he said. It’d also be helpful, he said, if people adhere to social-distancing guidelines to help flatten the curve.

That said, the coronavirus pandemic is taking a toll on Smith.

“I’m no stranger to death, illness, and the American healthcare system, because I’ve been in it for over a decade,” he said. “But I’ve never seen what I’ve been seeing lately with the speed, intensity, and spread of the virus itself, and its impact on patients and the hospital system.

“It does take a toll,” he added, “but, you know, there’s not really any other option at this point.”

The government is failing people rather than safeguarding their health, Smith said

Smith said his frustration with the healthcare system’s “sad” state “peaked” the day he posted on Facebook.

His interaction with the patient underscored how worries about affording medical care “disincentivize people from wanting to even seek treatment,” he said. That’s “inherently problematic” in the context of a pandemic because people put a heavier “burden on the system when they come in so acutely ill,” Smith said.

He said he thinks that a “tertiary care setting, where people come into the ED with or without insurance,” was “far from the best way to do it.”

“There should be a better emphasis on primary prevention, public health, and also the ability to pay for [healthcare] regardless of your social or class status,” Smith added.

It doesn’t compute to see thousands of people a year dying from a lack of access to medical care in “one of the richest industrialized nations in the world” or being forced to crowdfund their treatment, Smith said, denouncing federal and state governments’ responses to the crisis.

He said President Donald Trump didn’t do enough with the Defense Production Act to actually “pick up the pieces of this mess” and left it to state officials to cull a “patchwork” of containment measures. He also criticized Wisconsin authorities for holding an election during a pandemic and forcing people to choose between their well-being and democracy, as well as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for shifting its guidelines about which face masks are safe to use.

“I believe the main purpose of a government is to protect and uphold its citizens, and I feel like that’s clearly not what’s taking place,” he said.

Correction: The headline of this story originally referred to Smith as an anesthesiologist. He is a nurse anesthetist.

Loading Something is loading.

Do you have a personal experience with the coronavirus you’d like to share? Or a tip on how your town or community is handling the pandemic? Please email [email protected] and tell us your story.

And get the latest coronavirus analysis and research from Business Insider Intelligence on how COVID-19 is impacting businesses.

More:

coronavirus

COVID-19

Derrick Smith

New York City

Chevron icon It indicates an expandable section or menu, or sometimes previous / next navigation options.

%%

from Job Search Tips https://jobsearchtips.net/coronavirus-patients-last-words-whos-going-to-pay-for-it/

0 notes

Text

Doctors in India are being contaminated, trolled and evicted as they battle coronavirus

Medical staffers at just a few hospitals have threatened to go on strike over an absence of kit.

Picture Credit score: DailyKhaleej

Mumbai: After a affected person at a hospital in northern India examined constructive for Covid-19, it wasn’t lengthy earlier than among the medical employees started displaying signs, too.

Doctors at Nalanda Medical School in Bihar state, in need of protecting tools, handled the affected person whereas sporting solely an ordinary surgical equipment — three-ply masks, gloves and plastic-coated apron. They ate in a multitude corridor shared by 83 docs, all of whom now fear they have been uncovered to the coronavirus.

However when the docs requested the hospital superintendent if they may very well be quarantined, they have been informed to maintain working. With a pandemic spreading — and in an impoverished state with only one authorities physician for each 28,000 folks — the hospital couldn’t afford to lose them. So they took treatment and saved seeing sufferers.

Because the World Well being Organisation warns of a world scarcity of medical tools in the Covid-19 pandemic, India’s beleaguered hospitals discover themselves preventing an accelerating outbreak with too few docs, well being employees, check kits, beds, ventilators, protecting gear, masks or different important provides.

Every week in the past, Prime Minister Narendra Modi known as for a nationwide clanging of plates to point out assist for well being employees. However after Kamna Kakkar, an anaesthesiologist in Haryana state, spoke out on social media concerning the lack of protecting tools — “When they arrive, send N95 masks to my grave,” she tweeted — Modi supporters hounded her on Twitter and known as her “fake doc”. She deleted her tweets and took her account non-public.

Doctors and hospital personnel are notably susceptible to contracting Covid-19, and the parlous state of India’s medical system has raised considerations that its well being employees might be uncovered to the virus in even higher numbers.

Medical staffers at just a few hospitals have threatened to go on strike over an absence of kit. Specialists fear that others will stop working because of sickness, quarantine or worry of being contaminated.

“Because we know we are exposed to the virus, we are always insecure,” stated Ravi Raman, a physician at Nalanda Medical School. “I used to live with my parents and sister, but I’ve moved to another apartment. I need to protect my family.”

India as one of many smallest well being care work forces per capita of any nation, with only one authorities physician for each 10,926 folks. (The WHO recommends a ratio of 1 physician to 1,000 folks.)

India’s public spending on well being care is among the many lowest of any main economic system. Personal hospitals deal with a rising share of sufferers, however most Indians lack medical insurance. That will increase stress on the federal government well being system, with some states now transferring to take over non-public amenities to struggle Covid-19.

Specialists say India’s failure to stockpile important medical provides might jeopardise the protection of entrance line medical professionals, risking a collapse of the well being system in the midst of a pandemic. Some scientists imagine that by mid-Could, India might have a whole bunch of hundreds of infections, that means it will run out of hospital beds.

“If the medical fraternity starts crumbling in this situation, things will spiral out of control,” stated Jerryl Banait, a Mumbai physician who has petitioned India’s Supreme Court docket to deal with the scarcity of protecting tools.