#but ill decide after i make a clara print

Text

Boddho, caress his roots

#pathologic#pathologic 2#Мор. Утопия#artemy burakh#linocut#art tag#so. i think its obvious that i finally got proper tools#including a blade that doesnt hurt my finger or a paper that is properly textured#ngl im thinking of redoing my danko print bcs of that#but ill decide after i make a clara print

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Last True Man- chapter 1/11

A crossover of Mary Shelley’s novels Frankenstein and The Last Man. Because TLM is an awesome pandemic novel and deserves more love!

Summary: A deadly plague has left Lionel Verney miserable as the last man on earth. Then he discovers a flier warning of an 8ft monster and decides to hunt the creature and reclaim the dominion mankind once held. But can he truly call himself the last man while abandoning everything that made humans human?

“I wandered lonely as a cloud,

That floats on high o'er vales and hills…”

--William Wordsworth

Ice had brought the once-great fountains of Rome to a standstill. A dusting of fresh snow cloaked the quiet streets in a white blanket, disturbed only by the hoof prints of horses picking their way past the overturned coaches that had once restrained them. Off the street, the towering doors of St. Peter's Basilica stood ajar to welcome the white flakes that blew in tiny circles across the cracked tile. I saw little reason to shut the dancing flecks out—today was a celebration!

“To a new year!” My voice echoed off the marble saint statues as I raised a crystal glass to the golden ceiling. Nearly tripping over my embroidered cloak, I ran across the cleared church to where my sweet Idris was shooing little Evelyn away from a flask of Rome’s finest wine.

“Idris, I fear we’ve raised a thief!” I chuckled, pushing the drink away from my son’s stubby fingers. I ruffled his hair and the curls tickled my palm. “Did Alfred put you up to this?”

I held my laughter as my other son’s head disappeared behind the towering statue of Saint Longinus. “Careful now, that monument was designed by mankind’s greatest minds!”

Taking Idris by the hand, we danced around the splotches of winter sun on the decorative tiles. Just as we’d done at Windsor Castle before evacuees fleeing the plague had crowded the rooms. I forced the image of their jutting ribs and dull eyes from my mind.

“And you’ll be baking mince pie this year, of course!” I forced a smile. “It is tradition after all! Clara loves them. Adrian too!” I guided Idris across the tile to where Adrian sat in a prince’s gown embedded with emeralds, laughing with my sister Perdita. Her eyes—once dulled from grief—had brightened. She adored the ruffly pink dress I had found for her. They all did. For my family, I would scour every continent if it brought a smile to their blue lips.

My head lifted to the ceiling in ecstasy. The golden walls and paintings blended in a whirlwind. We swung faster and faster, my laughter floating to the rafters to make up for the other's silence. I laughed and laughed.

And laughed.

My knees hit the tile and Idris clanged beside me before rolling into the shadows. The remaining suits and dresses I had hung on wireframes loomed above me. Never to be worn by man or woman or son or wife or friend again. The laugher turned to sobs.

“To 2100—the last year of the world!”

The candlelight gave the saint’s chiseled faces an imitation of life. It was too much, and my palms pressed against the lakes forming in each eye. A low whine came from my left as a warm tongue licked the frozen tears from my cheeks. My hands fumbled around until locating the shaggy fur and pulling the dog close.

“What are we to do, Bysshe?” I sobbed into the sheepdog’s warm pelt. “No one has entered Rome. None will ever come. I thought the knowledge stored here would sustain me as it did when Adrian introduced me to the finer aspects of society, but what use is studying the history of a dead race? Why walk through streets crowded with sculptures and theaters reduced to sheltering wild beasts?” I glared at the wireframe dressed in a prince’s clothing.

“Adrian, why did you pluck me from a life of savageness and show me what living could be only to die and leave me alone? Why couldn’t I have perished as a stubborn loner in the countryside instead of wandering through these marble and gold skeletons of humanity?”

The Adrian-frame remained silent. Bysshe whined again, and my voice softened. “No, you’re right, Bysshe. 'Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all.' I cherish the memories of those far more deserving of life than I.”

But memories were all they were. I thought of Adrian extending his hand to me on our first meeting. I had been crouching bloodied and wounded against an oak—a feral animal sustained by spite. He had looked past my hatred with the faith I could be saved from myself. Suddenly my patheticness dawned on me. This display of misery would achieve nothing. Adrian never stopped believing in the good of humanity. As the final remnant of our species, that legacy lived on through me alone.

“Bysshe, we’re leaving.” Standing, my gaze swept over the empty evening gowns and suits I’d so carefully positioned around the church. I turned toward the entrance. Purpose made each step firm on the tile, sending a strong clack through the halls.

“Fate has spared me alone, so I shall live.”

*

The preparations for my exodus were swift. I found a rowboat in decent shape tethered to the docks and a surplus of Indian corn stockpiled behind the stage of a dark theater. The gnawed bones of the ill-fated owner gave no complaint as I hauled the jars away.

Having secured transportation and food, I entered the library for more relics. The titles told me what was fiction, history, and societal critiques, but what did the written word mean to the termite seeking a meal? Though the libraries of the world were thrown open to me, I could not leave Rome’s archives to nature’s destruction. They were the sole link connecting me to the recollections of my ill-fated species. I stuffed my satchel until the flap couldn’t be fastened and departed.

Outside, Bysshe abandoned a squirrel he had cornered up an overgrown pine and joined me for a final pass down the empty streets. We reached the docks in good time, where a large fishery towered above us. It was likely visible for miles on the open sea. Something twisted within me. Placing my satchel beside Bysshe, I ordered him to stay and rushed back into the city.

*

The small rowboat bobbed in the waves. My final moments in Rome had been rash. Childish, even. Yet some part of me still clung fervently to hope. My painted message in every language I could cram on the fishery’s wall faded as we drifted into unknown waters.

Survivor!

You are not alone!

Sail south along the coast, and you shall find the tiny bark,

freighted with Lionel Verney—the LAST MAN.

#frankenstein#Mary Shelley The Last Man#The Last Man#Lionel Verney#frankenstein fanfiction#The Last Man fanfiction#dystopia

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Ossian’s lyricism’: Portuguese women’s translations

The following guest post comes from Gerald Bär of Universidade Aberta, whose publications include many important contributions to Ossian Studies. A fuller treatment of the topic of this post can be found in his article for Translation and Literature, “‘Ossian fürs Frauenzimmer’? Lengefeld, Günderrode, and the Portuguese Translations of ‘Alcipe’ and Adelaide Prata.”

When deciding on the title for my Portuguese translations of Ossian, I had to choose between ‘poemas’ and ‘poesias’. Bearing in mind the remarkable lyrical aspect in the reception and perception of the Ossianic poems, I used the latter word in order to emphasize their emotional and sentimental impact: Poesias de Ossian: Antologia das traduções em português (Lisbon, Universidade Católica Editora, 2010).

What was so appealing about Macpherson’s Bard? Being the last of his race, he presents tragic love of epic dimensions; heroism with nationalistic undertones; scenarios of the ‘sublime’; faithful commitment; passion; premature death; joy of grief. More than enough reasons, perhaps, to explain the female fascination for Ossian in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Ossian’s popularity becomes only too evident when we consider the many woman translators who contributed to the numerous translations of Macpherson’s publications and their lasting impact. Schiller’s wife, Charlotte von Lengefeld (1766-1826), and Karoline von Günderrode (1780–1806) showed a preference for ‘Darthula’, a short Ossianic poem included in the volume Fingal (1762). The Marquesa de Alorna (1750-1839) translated ‘Darthula’ into Portuguese, making use of Le Tourneur’s version of 1777. In her posthumously published translation she emphasizes ‘the melancholic tone in all of Ossian’s compositions, which mainly derives from the description of nocturnal scenes, lingering with pleasure on sombre and majestic objects’. [i]

By the time Fingal was translated into Portuguese the previously politically controversial national epic had become less polemical through the different emphasis given by its reception abroad and through its musical treatment. Composers such as Désiré-Alexandre Batton (Fingal (1822), Caterino Cavos, (Fingal i Roskrana, a three-act opera, 1824) and Gaetano Solito (Fingal: dramma lirico in tre atti by posto in musica dal Maestro Pietro Antonio Coppola, 1848), applied the genre of romance or scène lyrique to the poems and transformed Fingal into a lyrical piece.

Besides the many woman-translators, the performing of Ossian as a musical piece also contributed to giving the female voice more prominence in the drama and narrative. Clara Novello’s acclaimed soprano made her one of the greatest British vocalists of her time from 1833 onwards. Amongst the most important works created expressly for Novello was Fingal by Coppola, a popular work which was a success for the singer, as she recollects in her Reminiscences:

Several operas have been written for me: “Fingal,” by Coppola, successful; “Cleopatra,” by . . . laughed off the stage; “Foscarini,” by Coen, not bad nor ill-received, and others I forget. A hospitable custom in Lisbon gave us all three or four days’ lodging in some hotel, during which to find permanent abodes for our six months’ stay. [ii]

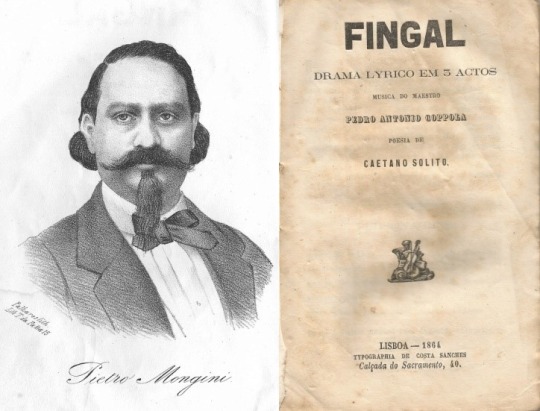

Clara Novello.

Coppola’s Portuguese libretto of Fingal (‘drama lyrico em 3 actos’, 1851) emphasizes the female role of Agandeca (sic), which gains a disproportionate importance, compared with Macpherson’s text. Coppola’s piece was put on stage on 21 April 1851 in the Royal Theatre of S. Carlos in Lisbon, repeated nine times and brought back in 1864 for another two presentations.

The Portuguese libretto of 1864 with P. Mongini as Fingal.

By that time, however, the leading figures and opinion-makers of Portuguese Romanticism, Almeida Garrett and Alexandre Herculano, had already adopted a more critical view of Ossian. Herculano did not include Fingal in his canon of ‘truly original epics’. [iii]

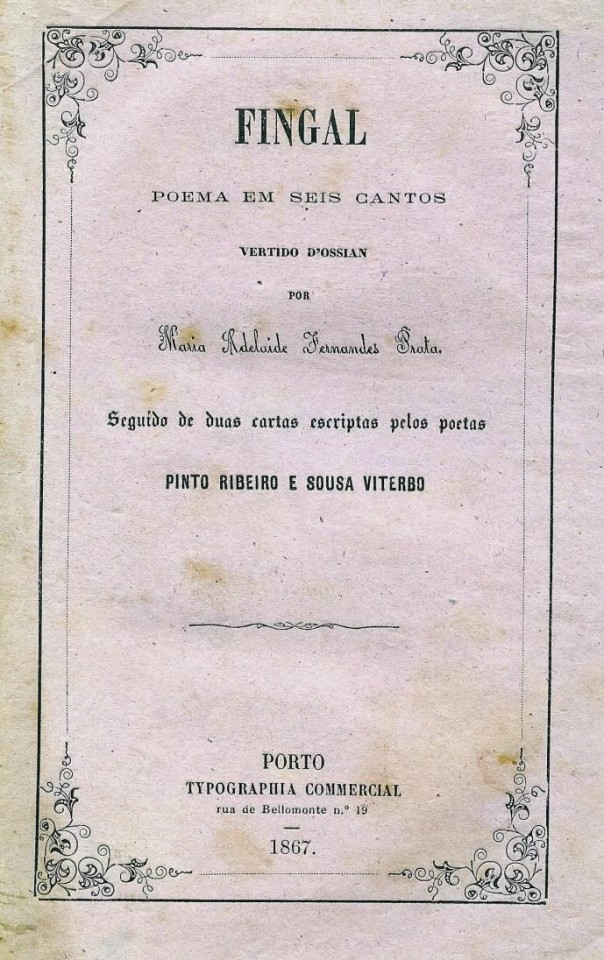

The first complete Portuguese translation of Fingal was published in 1867 in Porto by Maria Adelaide Fernandes Prata (1826-81), prefaced by two letters of the poets Pinto Ribeiro and Sousa Viterbo:

Porto edition of Fingal (1867).

It is possible that she had been inspired for her work by Novello’s performance or by its reviews. Similar to the Marquesa de Alorna’s Ossian translation, it too is reliant on Le Tourneur, who had used the 1765 Works edition, but it includes neither Macpherson’s notes, nor his Dissertations. In his eulogy Pinto Ribeiro considers Prata’s translated verses to be of the highest harmony, asserting that only a woman can produce real poetry. She can compensate for ‘formal defects with the grateful perfume of love and belief, fanciful lyricism, exquisite sensitivity and sentences of naïve simplicity, which male poetry can never achieve’. As he classifies Fingal not expressly as an epic poem, but as ‘one of the most beautiful little poems of the Homer of the North’ (‘um dos mais bellos poemetos do Homero do Norte’), the translator’s supposed childlike feminine ingenuousness seems to match the attitude expressed in natural and original, ‘formless’ folk poetry. Prata’s versification makes Sousa Viterbo rave about the ‘pure seraphic language’ of the ‘Scottish Homer’, with ‘its dithyrambs’ composed ‘of tenderness, melancholy, softness, delirium and passion’ (Prata, p. 14). These observations by the eminent poet Sousa Viterbo carry the weight of nineteenth-century gender and genre expectations. As already mentioned, the Portuguese Fingal does not include any of Macpherson’s notes, and excludes his and Blair’s academic dissertations. Categorising Fingal as ‘rather a lyrical than an epic poem’, Sousa Viterbo’s contribution to the volume thus relieves the translator of the supposedly masculine task of providing a lengthy literary-historical introduction to Fingal or having to supply academic notes. Its narrative, suspended by songs, and its descriptive elements always giving way to recitative parts, makes him ‘think more of the Romantic genre than of classic style of Antiquity’ (Prata, p. 16).

After appreciating the translator’s excellent choice and the accuracy and elegance of her work, Sousa Viterbo embarks on a detailed and effusively enthusiastic examination of Ossian, ‘the great poet’: ‘He has the roughness of primitive ages but it is this roughness that makes the heart a slave and the intellect a convinced admirer’ (Prata, p. 10). In his nineteenth-century view concerning the subject’s suitability for the fair sex, the poem’s ‘lyrical’ and romantic character, its inherent melancholy, the themes of love and poetry and ‘the female figures, so delicately and sensitively outlined’ by Ossian, makes Fingal perfectly suited for women translators. When Adelaide Prata’s translation came out the Ossianic subject had certainly changed from epic to epigonal, a fact made evident by many imitations and re-mediations (operas, theatre plays). However, despite the somewhat double-edged praise for its female translator, the Portuguese Fingal never saw a second edition, although the first was rather limited, inexpensive (500 réis) and inconspicuous compared to the impressive volume of 1762 (4to., 22.75 x 20cm), printed for Becket and De Hondt, in the Strand.

[i] D. Leonor D’Almeida Portugal Lorena e Lencastre Marqueza D’Alorna, Obras Poeticas, 6 vols (Lisbon, 1844), III, p. 289.

[ii] Clara Novello, Clara Novello’s Reminiscences. Compiled by her Daughter Contessa Valeria Gigliucci, with a Memoir by Arthur D. Coleridge, (London, 1910), pp. 138-146.

[iii] Alexandre Herculano, Opúsculos, edited by Jorge Custódio e José Manuel Garcia, (Lisbon, 1986), V, p. 213.

0 notes