#conularia

Text

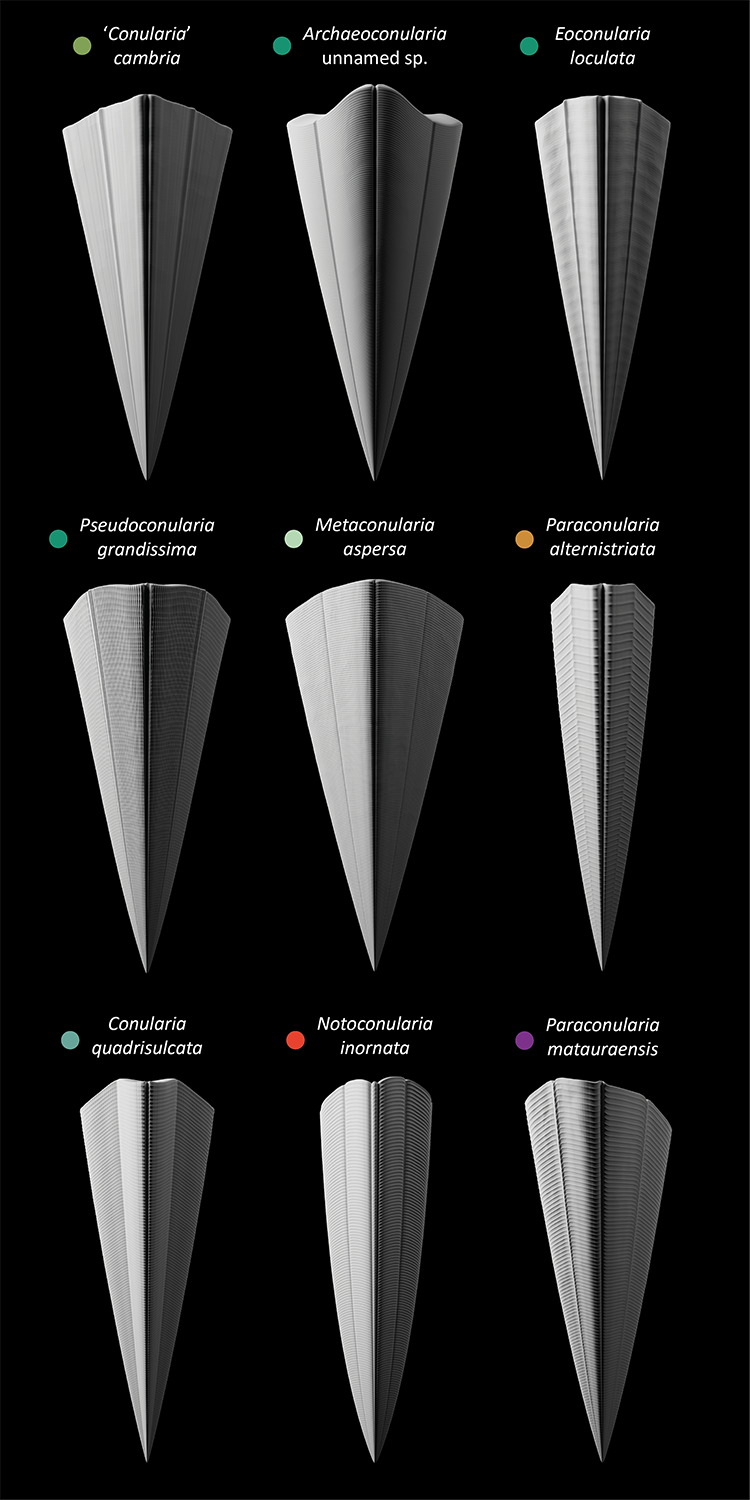

Conulariids are an extinct group of probable cnidarians with 4-sided pyramidal thecae. They are relatively uncommon fossils but ranged from the Cambrian (possibly Ediacaran?) to the Triassic, comprising tens of genera and hundreds of described species (Lucas 2012).

Here are the reconstructed thecae of a small selection of species from every period of the conulariids' range, starting from the Cambrian in the top left and reaching all the way to the Triassic in the bottom right.

Since their soft parts are virtually never preserved (due to them being cnidarians and all that) (Van Iten & Südkamp 2010), most of our knowledge of conulariid biology and evolution is based on their more fossil-friendly thecae, which were composed of thin organophosphatic lamellae (Leme et al. 2008). Live conulariids were attached to the substrate by the apex of their theca; they probably captured suspended food particles or small prey using tentacles, just like other cnidarians, but it's hard to go in any more (non-speculative) detail without preserved soft tissues.

References:

Babcock, L. E. (1986). Devonian and Mississippian conulariids of North America. Part B. Paraconularia, Reticulaconularia, new genus, and organisms rejected from Conulariida. Annals of the Carnegie Museum, 55, 411–479. https://doi.org/10.5962/p.215204

Guimarães Simões, M., Coelho Rodrigues, S., Moraes Leme, J. de, & Van Iten, H. (2003). Some Middle Paleozoic Conulariids (Cnidaria) as Possible Examples of Taphonomic Artifacts. Journal of Taphonomy, 1(3), 163–184.

Hughes, N. C., Gunderson, G. O., & Weedon, M. J. (2000). Late Cambrian Conulariids from Wisconsin and Minnesota. Journal of Paleontology, 74(5), 828–838. https://doi.org/10.1666/0022-3360(2000)074<;0828:LCCFWA>2.0.CO;2

John, D. L., Hughes, N. C., Galaviz, M. I., Gunderson, G. O., & Meyer, R. (2010). Unusually preserved Metaconularia manni (Roy, 1935) from the Silurian of Iowa, and the systematics of the genus. Journal of Paleontology, 84(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1666/09-025.1

Leme, J. M., Simões, M. G., Marques, A. C., & Van Iten, H. (2008). Cladistic Analysis of the Suborder Conulariina Miller and Gurley, 1896 (cnidaria, Scyphozoa; Vendian–Triassic). Palaeontology, 51(3), 649–662. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00775.x

Lucas, S. (2012). The Extinction of the Conulariids. Geosciences, 2, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences2010001

Sendino, C., & Zagorsek, K. (2011). The Aperture and Its Closure in an Ordovician Conulariid. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 56, 659–663. https://doi.org/10.4202/app.2010.0028

Slater, I. L. (1907). A monograph of British Conulariæ. Printed for the Palæontographical Society.

Thomas, G. A. (1969). Notoconularia, a New Conularid Genus from the Permian of Eastern Australia. Journal of Paleontology, 43(5), 1283–1290.

Van Iten, H., Konate, M., & Moussa, Y. (2008). Conulariids of the Upper Talak Formation (Mississipian, Visean) of Northern Niger (West Africa). Journal of Paleontology, 82(1), 192–196. https://doi.org/10.1666/06-083.1

Van Iten, H., Muir, L., Simões, M. G., Leme, J. M., Marques, A. C., & Yoder, N. (2016). Palaeobiogeography, palaeoecology and evolution of Lower Ordovician conulariids and Sphenothallus (Medusozoa, Cnidaria), with emphasis on the Fezouata Shale of southeastern Morocco. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 460, 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.03.008

Van Iten, H., & Südkamp, W. H. (2010). Exceptionally preserved conulariids and an edrioasteroid from the Hunsrück Slate (Lower Devonian, SW Germany). Palaeontology, 53(2), 403–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4983.2010.00942.x

Waterhouse, J. B. (1979). Permian and Triassic conulariid species from New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 9(4), 475–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.1979.10421833

敏郎杉山. (1942). 156. 日本産Conularidaの研究. 日本古生物学會報告・紀事, 1942(25), 185-194_1. https://doi.org/10.14825/prpsj1935.1942.185

#conularia#archaeoconularia#eoconularia#pseudoconularia#metaconularia#paraconularia#notoconularia#conulariid#cnidarian#paleozoic#mesozoic#palaeoblr#paleoart#my art

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion Month #07: Phylum Cnidaria – The Weird Ones

Odd shell-like structures that resemble angular ribbed cones with four-way symmetry appear in the fossil record starting around the mid-to-late Cambrian (with a possible Ediacaran record).

Known as conulariids, these fossils are so distinctive and different from anything else that for a long time their evolutionary affinities were unknown, and they were considered to be a "problematic" group. But in recent years they've been identified as being cnidarians, generally thought to be close relatives of modern stalked jellyfish.

Conularia cambria was one of the earliest definite conulariids, known from the states of Wisconsin and Minnesota, USA, and dating to the Late Cambrian (~490 million years ago). Up to about 5cm long (2"), its shell lacked the ribbed texture of most other conulariids but it would have otherwise looked very similar to later species – living attached to the sea floor by the pointed end of the cone, with tentacles protruding from the wider end at the top.

Conulariids were also unique among cnidarians for producing pearls inside their shells similar to those found in molluscs.

And despite being relatively rare and low-diversity, conulariids were a surprisingly long-lived group. Not only did they last throughout the rest of the Paleozoic Era, but they then survived the Great Dying mass extinction at the end of the Permian and only went completely extinct at the end of the Triassic, about 201 million years ago.

———

Another unusual fossil from the mid-Cambrian Chengjiang biota in southwest China (~518 million years ago) might have been a cnidarian. Xianguangia sinica was a tiny 2cm tall (0.8") sea anemone-like animal with a cylindrical body, an attachment disc at the bottom, and an upper whorl of around 16 tentacles with feather-like extensions that suggest it was a filter-feeder.

It's generally considered to be a "stem-cnidarian", part of an extinct early lineage that has no close modern relatives. It might represent a weird offshoot that experimented with a different body plan and feeding strategy than the rest of the group, or it might be a late-surviving example of what ancestral cnidarians originally looked like.

But other studies have instead linked it with potential ancestors of comb jellies, so its classification is still rather uncertain.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Pillowfort | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion 2021#conulariida#conularia#staurozoa#medusozoa#cnidaria#xianguangia#stem-cnidarian#maybe#eumetazoa#animalia#art

92 notes

·

View notes