#creator: 三川z

Text

Writing 天官賜福 (TGCF)

[eng by me]

272 notes

·

View notes

Text

ESSAY: Berserk's Journey of Acceptance Over 30 Years of Fandom

My descent into anime fandom began in the '90s, and just as watching Neon Genesis Evangelion caused my first revelation that cartoons could be art, reading Berserk gave me the same realization about comics. The news of Kentaro Miura’s death, who passed on May 6, has been emotionally complicated for me, as it's the first time a celebrity's death has hit truly close to home. In addition to being the lynchpin for several important personal revelations, Berserk is one of the longest-lasting works I’ve followed and that I must suddenly bid farewell to after existing alongside it for two-thirds of my life.

Berserk is a monolith not only for anime and manga, but also fantasy literature, video games, you name it. It might be one of the single most influential works of the ‘80s — on a level similar to Blade Runner — to a degree where it’s difficult to imagine what the world might look like without it, and the generations of creators the series inspired.

Although not the first, Guts is the prototypical large sword anime boy: Final Fantasy VII's Cloud Strife, Siegfried/Nightmare from Soulcalibur, and Black Clover's Asta are all links in the same chain, with other series like Dark Souls and Claymore taking clear inspiration from Berserk. But even deeper than that, the three-character dynamic between Guts, Griffith, and Casca, the monster designs, the grotesque violence, Miura’s image of hell — all of them can be spotted in countless pieces of media across the globe.

Despite this, it just doesn’t seem like people talk about it very much. For over 20 years, Berserk has stood among the critical pantheon for both anime and manga, but it doesn’t spur conversations in the same way as Neon Genesis Evangelion, Akira, or Dragon Ball Z still do today. Its graphic depictions certainly represent a barrier to entry much higher than even the aforementioned company.

Seeing the internet exude sympathy and fond reminiscing about Berserk was immensely validating and has been my single most therapeutic experience online. Moreso, it reminded me that the fans have always been there. And even looking into it, Berserk is the single best-selling property in the 35-year history of Dark Horse. My feeling is that Berserk just has something about it that reaches deep into you and gets stuck there.

I recall introducing one of my housemates to Berserk a few years ago — a person with all the intelligence and personal drive to both work on cancer research at Stanford while pursuing his own MD and maintaining a level of physical fitness that was frankly unreasonable for the hours that he kept. He was NOT in any way analytical about the media he consumed, but watching him sitting on the floor turning all his considerable willpower and intellect toward delivering an off-the-cuff treatise on how Berserk had so deeply touched him was a sight in itself to behold. His thoughts on the series' portrayal of sex as fundamentally violent leading up to Guts and Casca’s first moment of intimacy in the Golden Age movies was one of the most beautiful sentiments I’d ever heard in reaction to a piece of fiction.

I don’t think I’d ever heard him provide anything but a surface-level take on a piece of media before or since. He was a pretty forthright guy, but the way he just cut into himself and let his feelings pour out onto the floor left me awestruck. The process of reading Berserk can strike emotional chords within you that are tough to untangle. I’ve been writing analysis and experiential pieces related to anime and manga for almost ten years — and interacting with Berserk’s world for almost 30 years — and writing may just be yet another attempt for me to pull my own twisted-up feelings about it apart.

Berserk is one of the most deeply personal works I’ve ever read, both for myself and in my perception of Miura's works. The series' transformation in the past 30 years artistically and thematically is so singular it's difficult to find another work that comes close. The author of Hajime no Ippo, who was among the first to see Berserk as Miura presented him with some early drafts working as his assistant, claimed that the design for Guts and Puck had come from a mess of ideas Miura had been working on since his early school days.

写真は三浦建太郎君が寄稿してくれた鷹村です。

今かなり感傷的になっています。

思い出話をさせて下さい。

僕が初めての週刊連載でスタッフが一人もいなくて困っていたら手伝いにきてくれました。

彼が18で僕が19です。

某大学の芸術学部の学生で講義明けにスケッチブックを片手に来てくれました。 pic.twitter.com/hT1JCWBTKu

— 森川ジョージ (@WANPOWANWAN) May 20, 2021

Miura claimed two of his big influences were Go Nagai’s Violence Jack and Tetsuo Hara and Buronson’s Fist of the North Star. Miura wears these influences on his sleeve, discovering the early concepts that had percolated in his mind just felt right. The beginning of Berserk, despite its amazing visual power, feels like it sprang from a very juvenile concept: Guts is a hypermasculine lone traveler breaking his body against nightmarish creatures in his single-minded pursuit of revenge, rigidly independent and distrustful of others due to his dark past.

Uncompromising, rugged, independent, a really big sword ... Guts is a romantic ideal of masculinity on a quest to personally serve justice against the one who wronged him. Almost nefarious in the manner in which his character checked these boxes, especially when it came to his grim stoicism, unblinkingly facing his struggle against literal cosmic forces. Never doubting himself, never trusting others, never weeping for what he had lost.

Miura said he sketched out most of the backstory when the manga began publication, so I have to assume the larger strokes of the Golden Arc were pretty well figured out from the outset, but I’m less sure if he had fully realized where he wanted to take the story to where we are now. After the introductory mini-arcs of demon-slaying, Berserk encounters Griffith and the story draws us back to a massive flashback arc. We see the same Guts living as a lone mercenary who Griffith persuades to join the Band of the Hawk to help realize his ambitions of rising above the circumstances of his birth to join the nobility.

We discover the horrific abuses of Guts’ adoptive father and eventually learn that Guts, Griffith, and Casca are all victims of sexual violence. The story develops into a sprawling semi-historical epic featuring politics and war, but the real narrative is in the growing companionship between Guts and the members of the band. Directionless and traumatized by his childhood, Guts slowly finds a purpose helping Griffith realize his dream and the courage to allow others to grow close to him.

Miura mentioned that many Band of the Hawk members were based on his early friend groups. Although he was always sparse with details about his personal life, he has spoken about how many of them referred to themselves as aspiring manga authors and how he felt an intense sense of competition, admitting that among them he may have been the only one seriously working toward that goal, desperately keeping ahead in his perceived race against them. It’s intriguing thinking about how much of this angst may have made it to the pages, as it's almost impossible not to imagine Miura put quite a bit of himself in Guts.

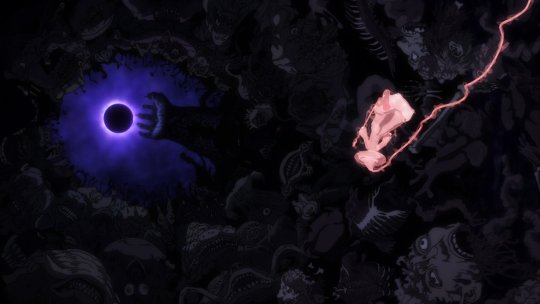

Perhaps this is why it feels so real and makes The Eclipse — the quintessential anime betrayal at the hands of Griffith — all the more heartbreaking. The raw violence and macabre imagery certainly helped. While Miura owed Hellraiser’s Cenobites much in the designs of the God Hand, his macabre portrayal of the Band of the Hawk’s eradication within the literal bowels of hell, the massive hand, the black sun, the Skull Knight, and even Miura’s page compositions have been endlessly referenced, copied, and outright plagiarized since.

The events were tragic in any context and I have heard many deeply personal experiences others drew from The Eclipse sympathizing with Guts, Casca, or even Griffith’s spiral driven by his perceived rejection by Guts. Mine were most closely aligned with the tragedy of Guts having overcome such painful circumstances to not only reject his own self enforced solitude, but to fearlessly express his affection for his loved ones.

The Golden Age was a methodical destruction of Guts’ self-destructive methods of preservation ruined in a single selfish act by his most trusted friend, leaving him once again alone and afraid of growing close to those around him. It ripped the romance of Guts’ mission and eventually took the story down a course I never expected. Berserk wasn’t a story of revenge but one of recovery.

Guess that’s enough beating around the bush, as I should talk about how this shift affected me personally. When I was young, when I began reading Berserk I found Guts’ unflagging stoicism to be really cool, not just aesthetically but in how I understood guys were supposed to be. I was slow to make friends during school and my rapidly gentrifying neighborhood had my friends' parents moving away faster than I could find new ones. At some point I think I became too afraid of putting myself out there anymore, risking rejection when even acceptance was so fleeting. It began to feel easier just to resign myself to solitude and pretend my circumstances were beyond my own power to correct.

Unfortunately, I became the stereotypical kid who ate alone during lunch break. Under the invisible expectations demanding I not display weakness, my loneliness was compounded by shame for feeling loneliness. My only recourse was to reveal none of those feelings and pretend the whole thing didn't bother me at all. Needless to say my attempts to cope probably fooled no one and only made things even worse, but I really didn’t know of any better way to handle my situation. I felt bad, I felt even worse about feeling bad and had been provided with zero tools to cope, much less even admit that I had a problem at all.

The arcs following the Golden Age completely changed my perspective. Guts had tragically, yet understandably, cut himself off from others to save himself from experiencing that trauma again and, in effect, denied himself any opportunity to allow himself to be happy again. As he began to meet other characters that attached themselves to him, between Rickert and Erica spending months waiting worried for his return, and even the slimmest hope to rescuing Casca began to seed itself into the story, I could only see Guts as a fool pursuing a grim and hopeless task rather than appreciating everything that he had managed to hold onto.

The same attributes that made Guts so compelling in the opening chapters were revealed as his true enemy. Griffith had committed an unforgivable act but Guts’ journey for revenge was one of self-inflicted pain and fear. The romanticism was gone.

Farnese’s inclusion in the Conviction arc was a revelation. Among the many brilliant aspects of her character, I identified with her simply for how she acted as a stand-in for myself as the reader: Plagued by self-doubt and fear, desperate to maintain her own stoic and uncompromising image, and resentful of her place in the world. She sees Guts’ fearlessness in the face of cosmic horror and believes she might be able to learn his confidence.

But in following Guts, Farnese instead finds a teacher in Casca. In taking care of her, Farnese develops a connection and is able to experience genuine sympathy that develops into a sense of responsibility. Caring for Casca allows Farnese to develop the courage she was lacking not out of reckless self-abandon but compassion.

I can’t exactly credit Berserk with turning my life around, but I feel that it genuinely helped crystallize within me a sense of growing doubts about my maladjusted high school days. My growing awareness of Guts' undeniable role in his own suffering forced me to admit my own role in mine and created a determination to take action to fix it rather than pretending enough stoicism might actually result in some sort of solution.

I visited the Berserk subreddit from time to time and always enjoyed the group's penchant for referring to all the members of the board as “fellow strugglers,” owing both to Skull Knight’s label for Guts and their own tongue-in-cheek humor at waiting through extended hiatuses. Only in retrospect did it feel truly fitting to me. Trying to avoid the pitfalls of Guts’ path is a constant struggle. Today I’m blessed with many good friends but still feel primal pangs of fear holding me back nearly every time I meet someone, the idea of telling others how much they mean to me or even sharing my thoughts and feelings about something I care about deeply as if each action will expose me to attack.

It’s taken time to pull myself away from the behaviors that were so deeply ingrained and it’s a journey where I’m not sure the work will ever be truly done, but witnessing Guts’ own slow progress has been a constant source of reassurance. My sense of admiration for Miura’s epic tale of a man allowing himself to let go after suffering such devastating circumstances brought my own humble problems and their way out into focus.

Over the years I, and many others, have been forced to come to terms with the fact that Berserk would likely never finish. The pattern of long, unexplained hiatuses and the solemn recognition that any of them could be the last is a familiar one. The double-edged sword of manga largely being works created by a single individual is that there is rarely anyone in a position to pick up the torch when the creator calls it quits. Takehiko Inoue’s Vagabond, Ai Yazawa’s Nana, and likely Yoshihiro Togashi’s Hunter X Hunter all frozen in indefinite hiatus, the publishers respectfully holding the door open should the creators ever decide to return, leaving it in a liminal space with no sense of conclusion for the fans except what we can make for ourselves.

The reason for Miura’s hiatuses was unclear. Fans liked to joke that he would take long breaks to play The Idolmaster, but Miura was also infamous for taking “breaks” spent minutely illustrating panels to his exacting artistic standard, creating a tumultuous release schedule during the wars featuring thousands of tiny soldiers all dressed in period-appropriate armor. If his health was becoming an issue, it’s uncommon that news would be shared with fans for most authors, much less one as private as Miura.

Even without delays, the story Miura was building just seemed to be getting too big. The scale continued to grow, his narrative ambition swelling even faster after 20 years of publication, the depth and breadth of his universe constantly expanding. The fan-dubbed “Millennium Falcon Arc” was massive, changing the landscape of Berserk from a low fantasy plagued by roaming demons to a high fantasy where godlike beings of sanity-defying size battled for control of the world. How could Guts even meet Griffith again? What might Casca want to do when her sanity returned? What are the origins of the Skull Knight? And would he do battle with the God Hand? There was too much left to happen and Miura’s art only grew more and more elaborate. It would take decades to resolve all this.

But it didn’t need to. I imagine we’ll never get a precise picture of the final years of Miura’s life leading up to his tragic passing. In the final chapters he released, it felt as if he had directed the story to some conclusion. The unfinished Fantasia arc finds Guts and his newfound band finding a way to finally restore Casca’s sanity and — although there is still unmistakably a boundary separating them — both seem resolute in finding a way to mend their shared wounds together.

One of the final chapters features Guts drinking around the campfire with the two other men of his group, Serpico and Roderick, as he entrusts the recovery of Casca to Schierke and Farnese. It's a scene that, in the original Band of the Hawk, would have found Guts brooding as his fellows engage in bluster. The tone of this conversation, however, is completely different. The three commiserate over how much has changed and the strength each has found in the companionship of the others. After everything that has happened, Guts declares that he is grateful.

The suicidal dedication to his quest for vengeance and dispassionate pragmatism that defined Guts in the earliest chapters is gone. Although they first appeared to be a source of strength as the Black Swordsman, he has learned that they rose from the fear of losing his friends again, from letting others close enough to harm him, and from having no other purpose without others. Whether or not Guts and Griffith were to ever meet again, Guts has rediscovered the strength to no longer carry his burdens alone.

All that has happened is all there will ever be. We too must be grateful.

Peter Fobian is an Associate Manager of Social Video at Crunchyroll, writer for Anime Academy and Anime in America, and an editor at Anime Feminist. You can follow him on Twitter @PeterFobian.

By: Peter Fobian

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing 以和為貴 (yi3he2wei2gui4; harmony is most precious) in the shape of a dragon for the Year of the Dragon

290 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing 魔道祖師 (MDZS)

106 notes

·

View notes