#does this make sense ? like I still agree w Europeans who want to resist Americanization its just. I have an iota less sympathy for them.

Text

re: lrb sorry I didn't rb that dutch addition on that post but it was like. TOO funny for me to take seriously. and it's something that SHOULD be taken seriously!! "globalization" is often another word for "destruction of localized language and culture/neo-colonialism" so like. very much on page w that post.

. .. but the dutch thing was TOO funny sdhshs

#LIKE. HELP. IDK WHAT TO TELL U. SHOULDNAE HAVE COLONIZED MANNAHATTA.#THE FOUNDING OF 'NEW AMSTERDAM' AND ITS CONSEQUENCES#like. I think with Western Europe the whole 'holy shit wait OUR language and culture can get wiped out too ? 😟 not just everyone else ??' is#a little like. a rather belated Monkey's Paw of colonialism. or less Monkey's Paw more unintended yet inescapable retribution.#does this make sense ? like I still agree w Europeans who want to resist Americanization its just. I have an iota less sympathy for them.#especially cus haha hey! now you're just like me! (3rd gen white immigrant) like losing your language ey ? to assimilate ? womp womp#comes for us all looks like

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Listening Post: Michael Cosmic — Peace in the World / Phill Musra Group — Creator Spaces (Part Two)

Following up on the part of the conversation posted earlier today, the Dusted crew continues to discuss these newly reissued free jazz records from 1974 Boston.

Mason Jones: I'm pretty outside the jazz realm, though in my years playing avant-experimental music I've crossed paths with a lot of free players, particularly the early '90s Oakland scene (Splatter Trio, Gino Robair, Pluto, and the like). I've dipped into jazz quite often from time to time but for some reason little of modern jazz resonates strongly with me. The expanses of this release that do, surprisingly, are those that breathe more slowly. John Coltrane's not my thing, but like others I also hear echoes of Alice Coltrane in parts of "Peace in the World" for example. Even though it doesn't really sound much like her work, it somehow feels similar. I dig the splashing, crashing drum solo in "The Creator Spaces" and find Ertunç's playing pretty evocative throughout. My deficiency in appreciating reeds certainly impedes my judgment on a lot of this, though, so I'll have to let others get deeper into it all.

Jonathan Shaw: Michael, by "otherness" earlier, you mean a form of alienation beyond being black? Something more musically mediated?

Michael Rosenstein: Good point! By "otherness," I was referring to musical practice. While the traditions of free jazz (and by the mid-70s, the language had developed traditions) were referenced by many of the musicians in Boston, they brought an outsider sensibility to things. That is certainly not unique to Boston, but it was something that certainly struck me when I was first hearing musicians like Voigt, Harvey, Davidson, and Smart (to name a few).

Jonathan Shaw: So interesting to think of a music that wants to articulate some principle of "freedom" developing traditions. Tradition isn't intrinsically reactionary, but that's the way the term often gets used these days—I think especially of how the term resonates in the Traditional Workers' Party. Assholes.

What's freedom's outside? Where can we hear it on these records? I don't know who coined the term "free jazz" and to what extent that usage of free speaks to other forms of Africanist and African American identity construction in 20th century culture; as I noted somewhere above, my sense of "free" in free jazz is liberatory, but in a nationalist sense, black as essentially other than white, and decidedly other than European. But that's not the only way to conceptualize things. Back in the 1920s, Alain Locke argued that black Americans were best positioned to fully embody the country's ethos of freedom and liberty, precisely because blacks understood the opposite of freedom and liberty like no one else. For some reason, I think Locke would be more attracted to Cosmic/Musra's music than he would to Archie Shepp c. 1970 or Braxton.

Derek Taylor: I’m not sure on the origin of the phrase “free jazz” earlier than Ornette’s composition/album of the same name, but that’s when it really started to gain traction as a descriptor. While the “free” is in there, so is “jazz” denoting a foundational framework around which the free elements center and revolve. The specifically Nationalist leanings came shortly after and were confounded in part by the prominent place of white players in the music: Charlie Haden w/ Ornette, Roswell Rudd w/ Archie Shepp, Alan Silva, etc. The free musical elements that Cosmic and Musra employ definitely sound on that axis to my ears while bringing in aspects in part apart from jazz tradition as well (the zurna, African/Latin percussion instruments, etc.)

Any musical idiom that has historical legs is naturally going to develop traditions. Even music as resolutely non-idiomatic as free improvisation has developed recognizable vocabularies over the years through the repeated use of extended techniques and other tools (a reason why Derek Bailey, despite his protestations against precedence and familiarity, is usually instantly recognizable). Tradition in the context of Cosmic/Musric seems like a way of preserving, celebrating older means of musical expression outside Western, or more ambiguously white, cultural standards. But I don't get the feeling that they're doing it from a position of any overt animosity or concerted resistance, but more from a place of naturalness and positivity.

Mason Jones: When I hear "free jazz" or "free music" I also inevitably think of LAFMS, which was coming at "free music" from a very different angle than the jazz cats, though with a lot of sympathy both ways. They were looking to unmoor music from pretty much all frameworks, while I still think of free jazz as identifiably "jazz" — it's leaving behind the traditions but somehow still employing a lot of the same thinking. The Cosmic/Musra set is undeniably jazz even at its most outré, and to me feels only partially "free" in this context. I agree that it doesn't sound reactionary, so I might say that it's aimed towards freedom of expression rather than freedom *from* anything, if you know what I mean.

Jonathan Shaw: Probably also worth noting that a bunch of free players had good times in Europe—Cecil Taylor, Art Ensemble of Chicago, Don Cherry.

Bill Meyer: When musicians operate from a jazz foundation, and when they think what they are doing continues to relate non-antagonistically to jazz, you have free jazz. European free improvisation was started by people who loved jazz, but felt that they could not contribute in a culturally primary way. To be a Briton or European who loved jazz was to love something that came from somewhere else, but they wanted to take the example of serious aesthetic advancement that they saw in Ornette/Coltrane/etc to heart. Some of them (Paul Lytton, I believe, has talked a lot about this) very self consciously cut themselves off from playing music they really loved in order to grow. Others were aware of not being a part of it but continued to use it as a touchstone - Evan Parker for example. And Brotzmann sees himself as a jazz musician, I think, even though he's quite willing to step outside of jazz.

Cosmic/Musra, I think, come from a specifically African-American angle. Presumably they aspired to play jazz before they arrived at the music that they play on this set. The beyond-jazz aspects of their music relates to a divergent stream of jazz (Sun Ra, John and Alice Coltrane, Pharoah Sanders, the AACM) that was reflects ways of expressing and defining identity that were current in the African-Amerian community. As a whole, this music reflects an interest in Africa and non-European cultural, a disinclination to accept mainstream narratives and perspectives at face value, and a valuation of strongly felt/expressed spirituality that made a lot of room for the esoteric.

Derek Taylor: There’s definitely a lot of anecdotal history in support of Jonathan’s point about Stateside versus European experiences for ex-pat free jazz players and jazz players in general. But it wasn’t all rosy for them either. Ayler (in)famously got booed and worse at stops on his first European tour and Coltrane/Dolphy were hit with critical devaluations even earlier for the avenues they opted to explore. That makes the brothers experiences intriguing by contrast. Yes, they came later after the groundwork had been established by forebearers, but they still experienced a pretty uniformly positive response to what they were doing, at least in Chicago and Boston, if not L.A.

Brötzmann’s relationship with and to jazz has been contentious throughout his career. I don’t think he has much use for the term as a descriptor for what he does and hasn’t for quite some time, although his own listening habits apparently tend toward the classicists (Sidney Bechet, Coleman Hawkins, etc. who were themselves somewhat ironically the revolutionaries in their day). Parker’s much more open about acknowledging and embracing his debts (to Coltrane especially).

I get the feeling that Cosmic/Musra’s core musical beliefs came out of the AACM. It’s where they ostensibly really learned to play their instruments. Musra tells the story of Roscoe Mitchell recruiting him, clarinet in hand, right of the beach. Earlier influences were in the African American church (both sang in the choir) and by proxy their father’s record collection/musical interests. So right off the bat neither was coming from any sort of traditional pedagogy, jazz or otherwise. They were steeped in the divergent stream Bill mentions almost from the start.

Jonathan Shaw: Thanks for the context, Derek. You mention the positive response the brothers' records got. Is that response recorded anywhere? Were any prominent jazz critics and/or thinkers writing about the brothers in the 1970s? It would be interesting to see how their contemporaries processed the sounds.

Bill Meyer: I think it's interesting to think about what we mean when we say tradition and what the brothers might have thought tradition meant. Free jazz in all its stripes was the New Thing, and the influences we've noted would have been, for the brothers, music from the last five or ten years. On the other hand we can think of a free jazz tradition because free jazz has been a label as long or longer than most of us have been alive.

Derek Taylor: Good questions, Jonathan & Bill. I was going off of Clifford Allen’s notes & other contextual information available over at his blog Ni Kantu. He’s talked/corresponded with Musra over the years and has gathered a lot of anecdotal context, although I get the impression that the positive response(s) as described was more at the audience/community level rather than a critical or establishment one. Lots of gigs, but pretty much under the radar of the conventional jazz/music press, although I could be mistaken.

The AACM was founded (at least formally) in May of 1965, which would mean that it was it was less than two years old when Mitchell ran into a teen-aged Musra on the beach. Hardly time enough to establish tradition in an orthodox sense. That in turn seems to imply that the traditions the brothers were interested in exploring were older, non-Western and not strictly observed, but rather interpretative jumping off points. It doesn’t sound like their formal instruction prior to AACM enrolment was very extensive at all.

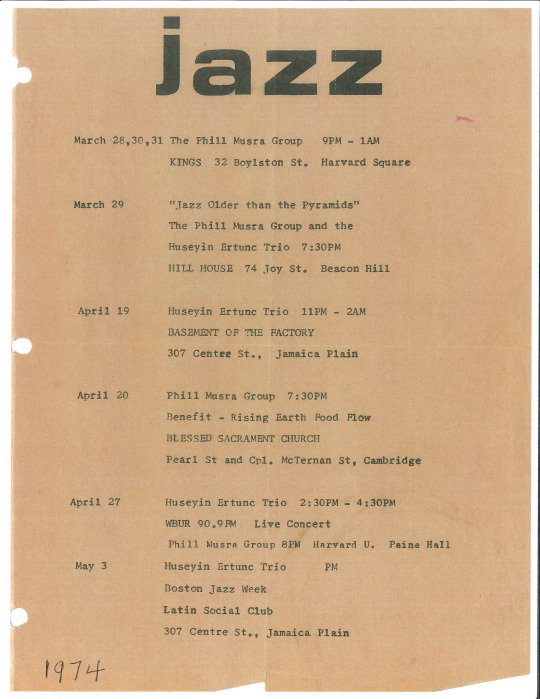

Michael Rosenstein: I wouldn't say that their records got particularly positive responses when they came out. They came out in such limited runs and distribution was so localized at the time. But they definitely played out a fair bit in Boston based on the documentation provided in Mark Harvey's book. There is a flyer that is reproduced from Spring 1974 that lists the following:

That's nine gigs within six weeks in clubs, churches, galleries, universities, radio, and a festival! And there are enough other flyers in the liner notes to the CD and Mark's book to show that this wasn't just a fluke. This provides some evidence as to how much they were integrated as musicians into the DIY jazz and arts communities in Boston at the time.

Derek Taylor: Nice! Appreciate the specifics from Harvey’s book, Michael. When you say responses, are you speaking to audiences or on the critical/journalistic end or both? The grass roots aspects to the brothers’ efforts are pretty pervasive from the nature of the gigs, to their chosen crew(s), to the DIY-nature of the recorded documents. A large slice of their overall charm from where I sit.

Jonathan Shaw: I'm also curious. I'm charmed (wrong word, but hope you all hear me) by the self-released aspect of the records. I come from punk musical and social backgrounds, so my touchstones are Dischord Records, scene reports in Maximum Rock n Roll, zine culture, etc. It's really cool to see the antecedents of those marginal modes of cultural production in Cosmic/Musra, Sun Ra, and so on. As with the free jazz, the punks were trying to find authentic community that could buttress their resistance to social convention in art and in life. I don't know how self-selected the choice to self-release was for Cosmic/Musra.

Michael Rosenstein: Ahhh. When I say that the records "didn't get positive responses," it was in the context of national/mainstream jazz journalism. I also checked the archives of the Boston Globe to see if there was any newspaper coverage but non popped up. But response seems to have been pretty solid within Boston based on the fact that they got radio play (on underground radio/college radio) and played around quite a bit. I agree about the DIY nature of the recorded documents, but I also hear that really extending into their overall musical sensibilities. Like Derek notes, you just need to look at the range of musicians they pulled in.

Self-produced, self-released small labels were definitely relatively prevalent at that time for jazz musicians. I remember going to New Music Distribution Service in the early 80s in New York and there were shelves upon shelves upon shelves of records, a large chunk of which were self-produced. Nice to see that this stuff is continuing to be mined and released.

Jonathan Shaw: Not to continue to allege a comparison, but the proliferation of punk small labels in the 1980s (SST, Alternative Tentacles, R Radical, Dischord, etc) signaled a deliberate choice on the part of some bands to remain outside the music industry. Most of that came out of a left-ish, anticapitalist stance that was more or less coherent, depending on the band; some wanted to gain as much control over the production process as possible, for ideological as well as aesthetic reasons. The loving song to Malcolm X on Cosmic's record is potentially interesting in this regard: X stressed the necessity for black neighborhoods to assert greater control over their local economies, so that wealth could be generated within the community and stay within the community.

Derek Taylor: I think the comparison between valuation of DIY approaches in punk and jazz communities is spot-on. As Bill mentioned earlier there's a long history of jazz artists starting their own labels or having labels started by others to advance their work/interests. That tradition carries through to this day, but was just as prevalent contemporaneously with this set. Hat Hut was just getting off the ground in Switzerland in 1974 as a conduit for Joe McPhee's output, which had earlier been fostered by Craig Johnson's CJR imprint and Giacomo Pelliciotti's Black Saint/Soul Note ventures were launched in similar fashion to steward Billy Harper's efforts. All three were fiercely artist-focused and remained so even when outside pressures/enticements attempted to lure them in other directions. History is also littered with jazz artists who accepted major label overtures only to be dropped when the returns on investment didn't manifest (Sonny Simmons, David S. Ware, Henry Threadgill, Arthur Blythe, etc.). It's not entirely clear whether Musra & Cosmic ever shopped their work to outside concerns, but based the energy the put into their enterprises top to bottom I kind of doubt it.

Bill Meyer: Yeah, Max Roach, Charles Mingus, and Mingus's wife Celia started Debut back in the 50s. Sun Ra and Alton Abraham started Saturn around the same time. It was not new. At the time that Cosmic and Musra made these recordings, I can't imagine that they had a lot of other options. It was a rough time for jazz, commercially speaking. And one thing the punks and indie rockers figured out that I think the jazz indies of past decades never did was how to put together touring and distribution networks.

Jonathan Shaw: 1974 was rough pretty much all around. I've been listening to the version of "Arabia" on the Phill Musra Group record this morning, which seems to me much tougher and dissonant than the longer take on Cosmic's. Even the cymbals on the shorter version have more attack to them. Alongside "Egypt," I can't help but think of the Yom Kippur War of the previous year, formation of OPEC, and the consequent gas shortages in the US. I wonder what it was like performing songs themed toward North African and Middle Eastern cultures at that time.

Bill Meyer: Recession, gas lines, Watergate... they were not salad days.

Michael Rosenstein: There are a bunch of labels started by jazz artists like the ones noted above along with Strata-East founded by Charles Tolliver and Stanley Cowell, and Cecil Taylor's short-lived Unit Core label. But, as Derek notes above, I would guess that Musra & Cosmic were driven more by just wanting to get their music out than by wanting to stay outside the music industry. There just weren't that many options around in the mid-70s for jazz musicians. If anything, I would put their efforts closer to the DIY cassette scene. From the liner notes, it looks like neither Cosmic Records or Intex Records (the two labels that put these out) pretty much existed only to release Musra & Cosmic's music and then disappeared.

Derek Taylor: Interesting question regarding the reception toward music referencing North African and Middle Eastern cultures in the mid-1970s. I doubt the audiences Cosmic & Musra were courting evinced any overt ire or issues, but you never know. A tangent and a much later case, but drummer Pete La Roca (in)famously attempted to bar the reissue of his 1965 Blue Note album Basra (a minor masterpiece, IMO) out of the purported opinion that the title was disrespectful to American troops that had died in Iraq.

Jonathan Shaw: Interesting info, Derek. My grade-school memory of the 1970s suggests that anti-mid-eastern sentiments kicked up a lot after the Islamic Revolution in Iran. I don't know how extensive or intense anti-Arab feeling was in the 73-74 oil shock or to what extent Africanist/African-interested jazz music would have been on that radar of hate.

On a different theme: Michael noted earlier that "The Prayer," on the record of previously unreleased stuff, doesn't feature either of the brothers. From the album booklet, it looks like the only of player of note to the rest of the collection is John Jamyll Jones. The decision to include what seems a relatively tangential piece—especially one of such length—is strange to me (it's a lovely piece). How influential a player was Jones? How extensive might his influence have been on the brothers?

Michael Rosenstein: My guess is that the inclusion was to provide context of other music in a similar vein that was happening in Boston at the time.

Derek Taylor: Jones led the World Experience Orchestra, another Boston band of which the brothers were members and had strong strong ties to NYC. Now Again reissued two albums as a two-fer package prior to the set under discussion here. I was excited prior to hearing Jones, but came away underwhelmed. The music just doesn't hold together as well and the use of singers and less skilled participants is more pronounced.

Jonathan Shaw: That's too bad. I'm listening to "The Prayer" again. Appropriate that it starts with a statement from Jones. I don't usually respond well to flutes, but the solo (notes credit the playing to Stan Strickland) really lights things up. I wonder how thematically significant the instrument's gentleness is, with respect to prayer. The strings also give the piece a sort of rapturous quality. There's some dissonance around the 17th minute, but it's not a dominant tone. Also, the audience's initially confused response to the coda is pretty great.

Michael Rosenstein: Back to the notion of comparing these releases to punk labels in the early 80s, I think a better comparison would be to the local rock bands in the late 70s who did small-run, self releases. There was a promo e-mail that got forwarded recently for a reissue of music by the Austin band Terminal Mind. From what I can tell from the info on the site this band wasn't known much outside of Austin at the time, put out a few EPs themselves that sold out quickly, and then recently got unearthed. Jenny can probably think of a bunch of other examples like this. I think it was just reasonably affordable to pull together a short-run EP/LP back then.

Derek Taylor: The Numero Group has kind of made that sort of thing their reissue forte over the years, first w/ a slew local/regional soul labels and later branching out to include rock, punk & other genres, even yacht rock.

Jonathan Shaw: The tack Michael suggests is how a bunch of those early-1980s labels started. SST was originally a vehicle for Black Flag to put out singles in LA. Once they figured out that it was possible, they invited some friends along for the ride.

Mason Jones: Exactly — similar to Slash, Dischord, and so forth. Even Industrial Records and Mute, for that matter!

Ian Mathers: Speaking of getting in late and miss some fascinating conversation... I can give a complete novice’s perspective, at least. I was delayed partly by the problems of fitting in listens of this pretty sprawling set (or sets?), but I have been following the conversation with interest and learning a lot, and really enjoying those listens when I have been able to fit them in. I have virtually no jazz vocabulary to discuss these with; I grew up with Kind of Blue and A Love Supreme and loved the latter, and have been able to get into four Miles Davis albums so far (In a Silent Way, A Tribute to Jack Johnson, On the Corner and, uh, Dark Magus) and although I've listened here and there to plenty of things (including some free or at least freer jazz) and usually enjoyed it, for whatever reason jazz just doesn't tend to be something I put on unless I think about it. I feel like I should personally apologize to Derek here (who's writing about I've been reading and enjoying here for years!).

What this means is that while I recognize most of the names that have been mentioned in relationship to the music here, and even have enough context and/or fuzzy memories of having heard them before that the references have made contextual sense to me, when I'm walking around listening to "The Prayer" I'm mostly thinking that the part where the bass and violin are most prominent (my favourite part) makes me think of, say, Astral Weeks meets the Dirty Three. So I apologize for an fumbling and/or ignorant cross-genre comparisons I might make.

The most unexpected part of the experience for me so far is that I pretty much instantly liked the Michael Cosmic and World Experience Orchestra material, the Phill Musra Group tracks took a little longer and honestly still aren't my favourite (although I don't dislike them). I was struck by Jonathan's comment about the Musra "Arabia" being a little tougher and more dissonant, which I agree with, because both of those things would normally make it my preferred version, but in this case in addition to those qualities this shorter version just feels a little less... colorful? Listening now I'm wondering if this isn't partially the production or even room tone, but those four Michael Cosmic tracks, especially the longer first two, just feel so vibrant and communal and joyful, and the Phill Musra tracks just feel a little more... considered? formal (if that's not a totally ridiculous descriptor for any of this music)? restrained? And I think because "Arabia" is the only shared track between the two I feel the contrast a bit more there. That being said I do really like "The Creator Is So Far Out" in particular.

My favourite track here though, by far, and for some of the same reasons I know Derek wasn't necessarily a fan, is "Space on Space". I am a repetition guy and even though the actual music is vastly different some of my love for "Space on Space" comes from the same part of me that adores Oneida's "Sheets of Easter" or the loops at the end of Liars' "This Dust Makes That Mud" and Massive Attack's "Antistar" or the many 20+ minute tracks by Muslimgauze I've heard over the years. And here with "Space on Space" maybe it's the fact that there is that continuing element that allows me to more fully appreciate the parts of the band that are peeling off and doing their own thing while the looping musicians vamp in the background. It's probably the most viscerally thrilling free jazz track I've heard, although again my prior experience is minimal.

It's been a real education reading the liner notes and the discussion here about the context surrounding the brothers and their music, not least because some of that confirms the feeling I was getting from this music as soon as I played it the first time (I wanted to go in blind, just in case I wound up being overly suggestible). I definitely want to keep this stuff around, although in the future I honestly might split it into three, because the situations where I'd want to hear the Michael Cosmic material versus the more meditative Phill Musra Group versus the even more laid back World Experience Orchestra track here would probably be different.

#Michael Cosmic & Phil Musra Group#michael cosmic#phill musra group#now-again records#now-again reserve#dusted magazine#listeningpost#mason jones#michael rosenstein#derek taylor#bill meyer#jonathan shaw#ian mathers

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Back in 1968, Alexi Panshin published a critical study of Robert A. Heinlein entitled Heinlein in Dimension (now available online at the link). His book had a rather odd history – you can find a one-sided account* of its story here – but it was a rather interesting overview of Heinlein’s works to that point. It does have its flaws, but – in its honour – I decided to entitle this essay Heinlein in Reflection.

First, a brief recap. Some months ago, I volunteered to do a Retro Review of Starship Troopers for Amazing Stories. Steve Davidson suggested I review the remaining two books in the three that Heinlein believed encompassed his politics; Stranger in a Strange Land and The Moon is a Harsh Mistress. Somewhere along the line, this turned into a review of Farnham’s Freehold and To Sail Beyond The Sunset. (Earlier, I also reviewed Podkayne of Mars, at least partly because I read a strongly negative review and felt the urge to reread the source material.) Looking back left me convinced of two things: first, Heinlein was far more diverse than his critics painted him (which became the subject of another essay) and, second, he was never as black as his critics painted him. Heinlein was, in effect, a man who was before his time and after his time, but never truly a man of his time.

Perhaps because of this, Heinlein and his legacy have been savagely attacked. The hoary old chestnuts of ‘racist’ and ‘sexist’ and ‘fascist’ have been trotted out of the stable and aimed at Heinlein, simply because Heinlein was not a man of our time. Some critics have latched on to tiny details – Meade’s lack of presence and characterization in The Rolling Stones, for example – and used it to accuse Heinlein of sexism. Others cherry-pick examples from Heinlein’s earlier works and use them to slam the author, while still others just point and shriek at Heinlein without bothering to apply any critical thought. One may argue – many do – that attacking Heinlein is attacking the roots of science-fiction itself, that the haters are motivated by spite and/or a simple refusal to accept Heinlein’s works on their own terms (The Rolling Stones is a book for young male teens; Starship Troopers is about another young man maturing). Others might point out, in response, that Heinlein lived in a world that, in many ways, was very different to ours. He saw further than most, but he still had his blinkers.

There is, if I can be blunt, an understandable tendency to assume that a writer’s characters are speaking for him, that their impulses and goals match the authors. Yet any author will tell you that that is simply wrong. An author must develop a sense of empathy, even for a fundamentally wrong character; an author must play fair with his characters, particularly the ones he doesn’t like. (Straw characters are rarely amusing, whatever the politics behind them.) Indeed, given how much Heinlein wrote, anyone who assumed that Heinlein agreed with his characters would have to believe that Heinlein suffered from multiple-personality disorder. At base, it is difficult to believe that Heinlein wanted both the worlds of Stranger in a Strange Land and Starship Troopers. They simply don’t go together. As Larry Niven put it:

There is a technical, literary term for those who mistake the opinions and beliefs of characters in a novel for those of the author. The term is ‘idiot’.”

One may think that this is a harsh judgement. And yet – looking back – critics have been happy to blame Heinlein for being what he was, a man who was born in 1907 and lived through a profound period of social and political change that, understandably, may not have sat well with him. Heinlein’s life – 1907-1988 – spanned both world wars, the cold war and all its assorted engagements, the fall of the European empires, the civil rights era and the loss of American innocence … Heinlein saw a lot. His experiences – and those of his country and world – shaped his development, as surely as my experiences shaped mine. Heinlein grew up in a profoundly unsafe world, where – eventually – the threat of nuclear annihilation arose to promise the destruction of everything he held dear; his critics grew to adulthood as the world stabilised – for a while – and the prospect of imminent death and destruction faded into the background. Heinlein never knew the safety (and immense comforts) we used to take for granted – and, in many ways, his harsh view of the universe was more practical than anything put forward today.

Looking at his career in reflection, I think it is possible to say certain things about Heinlein that shine through his books. It is, of course, impossible to say for sure, but … I think it works. (And someone else will call me an idiot. That is the way of the world <grin>.)

Heinlein was, I think, a dichotomy. Just as Stranger in a Strange Land and Starship Troopers represented, for a while, the bibles of both Left and Right, Heinlein himself was a complicated mixture of cold-blooded realist/pragmatist and hot-blooded fantasist. He knew too much about humanity – particularly men – to fully embrace the more rationalist (in the sense that their characters are rational) worldviews of some of his successors, but – at the same time – he wanted people to be better. He was aware – realistically speaking – of how society’s chains held people, particularly women and blacks, in bondage, yet he also preached of worlds where those chains had been left in the past and forgotten.

It sometimes produced odd results. Hazel Stone, of The Rolling Stones, is an engineer, yet she faced considerable resistance from men in a male-dominated field (and eventually retired to raise her son). It isn’t actually clear if she gave up or not, unlike the main character of Delilah and the Space Rigger, who kept going until she had proved herself. It is clear that she advises her granddaughter, eighteen-year-old Meade, not to go into engineering even though she has the talent – a bad piece of advice or a practical one, given that Meade would have to work hard to prove herself? (Notably, Heinlein never suggests that barring women from engineering is a justifiable attitude; an alternate view of the whole situation might suggest that Hazel’s attitude ruffled too many feathers.)

Indeed, Meade is treated as the subject of a somewhat dishonest review of The Rolling Stones, which may as well serve as a good example of attacks on Heinlein himself. At the start, she is told to stay still … which the reviewer condemns … except she’s being painted, so she has to stay still. Later on, the adults wonder if she is ‘husband-high’ – i.e. old enough to get married. Which sounds awfully sexist, except for the minor detail that she might be spending a large chunk of her early twenties on a interplanetary freighter with no eligible men – a potential problem for someone of her age (and someone who has already shown an interest in men).

Odder still, this same dichotomy between realism and fantasy shows up in Farnham’s Freehold, Heinlein’s most controversial work. Farnham himself concedes that Joe – a black man – would make a good husband for his daughter, but notes that – at the same time – he would not advise such a marriage if they’d stayed in the distant past. The problems facing men and women in interracial marriages were stupendous, at the time. Is Farnham a realist or a racist? It can be argued both ways.

Heinlein did, I think, understand men very well. His grasp of male psychology was far better than most of his successors, although his grasp of female psychology was poor. He expected people to try to be better, but – at the same time – he didn’t condemn them for being what they were. Many of his juvenile novels were successful, at least in part, because he understood what his audience actually wanted. He understood the forces that shape the male mindset and suggested ways to push them in useful directions, instead of alternatively pretending that they didn’t exist or trying to crush them. Heinlein would not, I think, have had any time for either MRA or MGTOW activists, but he would have understood them. His male characters were recognisably human, even when their adventures were set in the far future. Heinlein preached the outwards urge, the desire to go on and found a new home. Our current stagnation owes much to the lack of a frontier.

This wasn’t really true of his female characters, although one could argue that they are reflections of their times too. Podkayne is a sweetly manipulative little teenage girl who reads poorly to our eyes, simply because her society doesn’t read like a natural outgrowth of ours. It is a curious combination of post-racial attitudes mingled with old-fashioned sexism, although it is clear that Poddy’s mother was a well-respected engineer in her own right. I think, at base, Heinlein simply wasn’t good at writing women. He could and did scatter references throughout his text to women who did ‘male’ jobs, but he was a great deal weaker when it came to using them as viewpoint characters. In some ways, indeed, he paid them the odd compliment of treating them as men, once they had been freed of society’s chains. Perhaps Heinlein’s greatest failure was not anticipating the effects – positive and negative – of feminism.

But this may be because of his early life. Heinlein grew up in a world that was very different from ours in many ways, even though it had a certain superficial similarity. (Indeed, many of his early works featured a background that was basically ‘USA IN SPACE.’) Because we don’t understand his world – and his assumptions about how it worked – his critics are quick to condemn. They do not see the past as a different country, nor do they try to engage its residents on their own terms. And while there have been many steps forward – many of which Heinlein predicted – there have also been some steps backwards. One of these, I believe, is a failure to grasp that human nature doesn’t change. Or that TANSTAAFL – There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch.

This theme became more pronounced throughout the later years of his writing. In Starship Troopers, Heinlein asks what right mankind has to survive. And he’s right. Why do we have a natural right to anything? The universe doesn’t give a damn about us. Heinlein had no illusions about the world. He knew that expansionist powers – Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union – had to be fought. The peace that prevailed in Europe after WW2 was not the result of natural law, but NATO’s willingness to fight (and that peace is now at an end). Superior military force was, in his view, the key to defending freedom.

Panshin argues that Heinlein’s later characters are focused on survival at all costs, while some of his other critics insist that Heinlein thought that women should have children first and only later have a career. This may be true, but … what’s wrong with survival? What is wrong with wanting one’s culture to survive? The universe rarely admits of neat and tidy solutions to anything … sometimes, you just have to grasp the nettle and fight. It’s a harsh viewpoint, in many ways, but it is true. The universe, like I noted above, simply doesn’t care.

There are people who insist that the destruction of the Native American societies was effectively a horrific genocide. They’re right. It was. But no amount of breast-beating will change the simple fact that it happened, or that human history tells us that the strong will always overpower the weak. (All those jokes about how different history would have been if the natives had an immigration policy have a nasty sting in the tail – immigrants did come to America and displace the natives. Why would anyone want to repeat that experience?) I think that Heinlein understood reality in a way many of his successors simply did not.

In his later years, Heinlein loved to shock. He would push forward controversial ideas – cannibalism, incest, etc – forcing his readers to actually think … and then question the foundations of their society. He asked questions that needed to be asked, although many of his answers were weak; he shocked, but then tried to show the consequences and downsides of breaking society’s rules. In doing so, he laid the foundations for much – much – more.

To some extent, as his career developed, Heinlein slowly shifted from writing adventure stories to writing literature. Many of his early works were thrilling stories for young men – often subjected to the editor’s pen – but his later works were more elaborate pieces of literature, more interested in developing their ideas than telling a story. (One of the reasons I didn’t like Starship Troopers as a young man was because it is a philosophical work, rather than an adventure story.) In some ways, it allowed him to get his ideas across, but – in other ways – it weakened them. He was still more effective, as a writer, when he didn’t hammer his ideas home. He trusted his readers. It is a lesson that many more modern writers could stand to learn.

Over the last few decades, there has grown up a belief that figures of the past can be judged by modern-day standards … and then rejected, when they – unsurprisingly – fail to live up to them. George Washington has been attacked for keeping slaves, even though he also saved the American Revolution and ensured that America would neither shatter into dozens of smaller countries nor turn into a dictatorship. Other figures have been subject to the same treatment, even though they were never men of our time. Heinlein, for all his contributions to the field of science-fiction (and a progressiveness that was quite shocking, by the standards of his time), has been blasted for not being progressive enough. He has been quoted out of context, reviewed with neither comprehension nor contextualisation and his supporters have been attacked for daring to support him. Very few people – and Heinlein knew this – are wholly good or evil. Heinlein was neither a angel nor a devil, but a man.

I’d like to finish by paraphrasing a quote from Jonathon Strange and Mr. Norrell that, I think, fits Heinlein like a glove.

It is the contention of modern critics that everything belonging to Robert Anson Heinlein must be shaken out of modern SF/Fantasy, as one would shake moths and dust out of an old coat. What does they imagine they will have left? If you get rid of Robert Anson Heinlein you will be left holding the empty air.”

***

(Editor’s note: while there are two sides to every story, Panshin’s accounting of the attempts by RAH to prevent the publication of Heinlein in Dimension and actions taken subsequently are supported by the historical record, as well as by eyewitness accounts privy to the “Good Day, Sir!” incident.)

(Editor’s second note: there is a wealth of coverage of Robert A. Heinlein, his works and his interactions with Fandom here on the site.)

Heinlein in Reflection Back in 1968, Alexi Panshin published a critical study of Robert A. Heinlein entitled Heinlein in Dimension…

0 notes

Link

Sanderson and Merck Caught Deceiving Consumers Dr. Mercola By Dr. Mercola In May 2016, I urged you to pressure poultry giant Sanderson Farms to come to its senses and join other major poultry producers in taking proactive steps to reduce its antibiotic use. Remarkably, the company not only decided not to reduce its usage but also took the step of going public with its decision to continue using antibiotics, saying the antibiotic-free chicken trend is nothing but a marketing ploy devised to justify higher prices. According to Lampkin Butts, president and chief operating officer of Sanderson Farms, "There is not any credible science that leads us to believe we're causing antibiotic resistance in humans."1 Yet, when the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) conducted an analysis of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) testing for multidrug-resistant E. coli on Sanderson Farms’ chicken, they found otherwise. Sanderson Farms’ Refusal to Cut Antibiotics in Chicken Is Dangerous Eighty percent of the antibiotics used in the U.S. are used by industrial agriculture for purposes of growth promotion and preventing diseases that would otherwise make their concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) unviable. With animals packed into tight quarters, fed unnatural diets and living in filth, disease flourishes. Low doses of antibiotics are added to feed as a matter of course, not only to stave off inevitable infectious diseases but also because they cause the animals to grow faster on less food. “But there is a terrifying downside to this practice,” Scientific American reported. “Antibiotics seem to be transforming innocent farm animals into disease factories.”2 The antibiotics may kill most of the bacteria in the animal, but remaining resistant bacteria is allowed to survive and multiply. When the FDA tests raw supermarket chicken, they routinely find antibiotic-resistant bacteria to be present. According to NRDC’s analysis of FDA data, this is also true of Sanderson Farms’ chicken:3 “[W]e graph[ed] FDA’s testing results for multidrug-resistant E. coli found on retail chicken and Sanderson Farms chicken from 2002 to 2014 … the graph shows that E. coli isolated from Sanderson Farms’ chicken had levels of multidrug-resistance that were similar to E. coli from all retail chicken tested. While FDA’s limited sample size makes it impossible to estimate national resistance rates with statistical confidence, it does provide evidence that Sanderson Farms chicken is indeed part of the problem and is contributing to the spread of antibiotic resistance (in addition to spreading E. coli, which can be harmful).” Other Chicken Producers, Including Perdue, Slash Antibiotics Usage While Sanderson Farms continues to dig in its heals and attempt to deceive the U.S. public that antibiotics belong in CAFO food production, other big names in the industry have made positive changes. Perdue announced in October 2016 that it had ended the routine use of antibiotics companywide, only using antibiotics when chickens get sick (in about 5 percent of their birds). They’re now marketing their poultry under a “no antibiotics ever” label. Perdue has stopped using not only antibiotics used to treat humans, but also ionophores, a class of antibiotics used exclusively in animals and more commonly in ruminant animals such as cows. The use of the antibiotic in poultry farming is to control parasitic illnesses in CAFOs, where disease spreads quickly. Perdue chairman Jim Perdue told NPR they’re eliminating antibiotics due to marketing reasons and consumer demand, noting "Our consumers have already told us they want chicken raised without any antibiotics.”4 The company is even using natural herbs and vitamins to help the chickens stay healthy. They put oregano in the chicken’s water and thyme in their feed to supply antioxidants and boost immune function.5 What Does It Mean When a Label Claims ‘Antibiotic Free?’ When sorting through “antibiotic free” labels available, it’s important to be aware of the “fine print” in some cases. In Perdue’s No Antibiotics Ever program, it means just that. However, if the label states only “responsible antibiotic use,” “veterinarian-approved antibiotic use,” “no antibiotic residue” or “100% natural,” antibiotics may have been used in the hatchery while the chick is in the egg. Even if a product is labeled organic, it could have had antibiotics used in the hatchery. The exception is if it is labeled organic and “raised without antibiotics.” In this case, it means no antibiotics were used at any point. Other loopholes include stating “no human antibiotics,” but this means other animal antibiotics may be used. Unfortunately, as Consumer Reports noted:6 “This still allows for the use of antibiotics that aren't medically important, which can lead to antibiotic resistance to other drugs. ‘Resistance genes don’t discriminate,’ says Tara C. Smith, Ph.D., associate professor of public health at Kent State University. Genes that create resistance to medically important antibiotics can tag along with what we think of as less crucial drugs, leading to similar consequences, in the long term, to using those critical ones.” Claims to watch out for include the “no growth-promoting antibiotics” label and the no “critically important” antibiotics label or claims. In the former case, it means antibiotics may still be used for disease prevention and in the latter, most critically important antibiotics aren’t used in poultry production anyway, so the “claim doesn't translate to meaningful change in antibiotic use,” according to Consumer Reports.7 While Perdue has made some meaningful changes in antibiotics usage, they’re still perpetuating the inhumane and unsustainable CAFO model, so the best place to get chicken and eggs is from a local producer, or raise them yourself. If you have to go commercial, definitely avoid companies continuing to use antibiotics, like Sanderson Farms, and support those committed to eliminating their use. I strongly encourage you to support the small family farms in your area. Merck Covers Up Pesticide Devastating Sea Life Corporate farms like Sanderson are not alone in their desire to deceive the public about a dangerous practice or product. In related news, pharmaceutical giant Merck, known as MSD Animal Health in the U.K., produces a pesticide called Slice, which contains emamectin benzoate and is used to kill sea lice — a major problem among farmed salmon raised in “CAFOs of the sea.” Slice persists in the salmon's tissues and the environment for weeks to months,8 and Scotland’s Sunday Herald reported in early 2017 that at least 45 lochs were contaminated with emamectin benzoate.9 It was previously revealed that the chemical may be hazardous to lobsters, crabs and other crustaceans inadvertently exposed,10 but a second report supposedly took major issue with the findings. It turns out that Merck had hired the reviewers to write a critique of the study in order to protect the reputation of their toxic pesticide and, worse, the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (Sepa) reportedly allowed it to happen. The Sunday Herald continued:11 “Merck’s behind-the-scenes influence has been exposed by more than 70 megabytes of internal documents released by the Crown Estate under freedom of information law. They also show that government and industry agreed not to issue a press release on the study. The revelations have been described as ‘extraordinary’ by environmentalists, who are demanding a ban on the pesticide. Merck said that the study had ‘limitations’ and the Scottish Government defended the anonymity of reviewers. We … reported that Sepa had suppressed a report about emamectin and ditched a plan to ban it after pressure from the fish farming industry. But until now the role of Merck has remained hidden.” Farmed Fish Are Spreading Disease The problems that occur on land do not disappear once intensive farming moves to the sea, which is why industrial fish farming, or aquaculture, is turning out to be just as damaging as land-based CAFOs. Raised in high numbers in crowded quarters, in unnatural environments and fed an unhealthy diet, “the consequence has been the emergence and spread of an increasing array of new diseases,” according to a review published in the journal Veterinary Research.12 Among them is heart and skeletal muscle inflammation (HSMI), which has been detected in farmed fish in Norway and British Columbia. HSMI has been responsible for devastating commercial fish farms in Norway, where it is considered the No. 3 cause of mortality, according to a 2015 annual report by seafood company Marine Harvest.13 There’s also the highly lethal infectious salmon anemia (ISA) virus, also known as salmon influenza. First detected in Norway in 1984, infection spread to other countries via egg imports. According to biologist Alexandra Morton, at least 11 species of fish in British Columbia’s Fraser River have been found to be infected with European-strain ISA virus, yet the Canadian food inspection agency has aggressively refuted the findings. Morton tested farmed salmon purchased in various stores and sushi restaurants around British Columbia, and samples tested positive for at least three different salmon viruses, including ISA, salmon alphaviruses and piscine reovirus, which gives salmon a heart attack and prevents them from swimming upriver. Worse still, Morton and colleagues have also found traces of ISA virus in wild salmon.14 For more details, check out the documentary “Salmon Confidential.” A February 2017 study published in PLOS One supports Morton’s findings: It identified HSMI on a British Columbia salmon farm15 and noted that outbreaks often occur after the fish are exposed to stressful events, such as algal bloom or treatment for sea lice.16 Avoid Being Deceived: Find Outlets for Safer, Humanely Raised Food The companies in favor of producing food on a mass scale have their profits, not your or the animals’ interests, at heart. The use of antibiotics and chemical treatments to kill sea lice are often regarded as a necessary cost of doing business, regardless of what it means for the future spread of antibiotic-resistant disease or welfare of the environment. Further, while CAFOs and fish farms promote the spread of disease, traditional farming practices combat it. At small, regenerative and diversified farms, where pigs, hens and cattle are raised together in a sustainable way, there are many reasons why disease is kept to a minimum, even without the use of antibiotics. The animals have more space to move around, for starters, making them hardier than those raised in confinement. They are weaned at a later age, which builds their immune systems. Even exposure to the sun, a natural sanitizer, is helpful, while a pig allowed to roll in mud enjoys a natural anti-parasitic. Scientific American further reported:17 “In a 2007 study, Texas Tech University researchers reported that pigs that had been raised outside had enhanced activity of bacteria-fighting immune cells called neutrophils when compared with animals raised inside.” You can do your part and help protect your health by rethinking where you buy your food. Choosing food that comes from small regenerative farms — not CAFOs — is crucial. While avoiding CAFO meats, look for antibiotic-free alternatives raised by organic and regenerative farmers. As for seafood, choose wild caught and MSC (Marine Stewardship Council) certified labels. As with other foods, your best bet may be to buy your fish from a trusted local fish monger.

0 notes