#does trnc have a tag??

Text

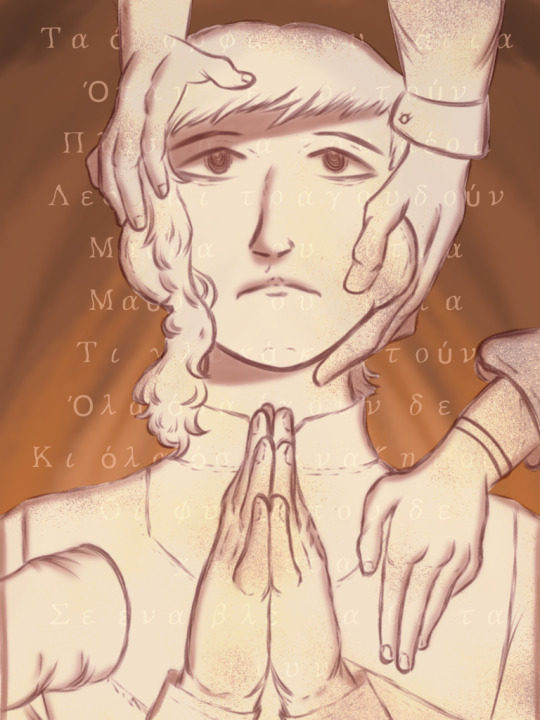

My piece for an art collab on discord!!I wanted to draw Cyprus so bad bro 😭 guess you can say Greece,Turkey,Egypt,and TRNC made a cameo too…

[Also,the Greek in the back is from Antonis Apergis’ “Black Eyes”.It’s a really pretty song!]

#hetalia#hetalia fanart#aph cyprus#hws cyprus#aph greece#aph turkey#does trnc have a tag??#aph egypt

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

this is totes random sorry pls feel free to ignore but is there a 'STATE' that's completely independent from like elected government, heads of state, partisan politics etc.. like what's this state that some ppl talk abt that doesn't include the elected president? e.g."korea and france have greater deference to state." is there polisci literature/concept on this? what is this STATE that doesn't include the president or CDC head nominated by said president? im sorry im just so ignorant of polisci

This is not at all an ignorant question! This is a huge issue people argue about--maybe less in poli sci than in other social sciences, because poli sci has gone so completely up its own quantitative ass that it has abandoned what should be its obvious theoretical domain and so other disciplines have kind of taken over this kind of question. There are full professors who cannot answer this question (I know because some of them are on my listservs).

So: what is the state. Seriously, really, there is no one widely accepted answer to this. So I’ll go through a few of them under the cut for you. This ended up being really long because it’s something I’ve been thinking about lately, so the simplest, shortest answer to your question is the first one.

1. Institutions

In this view, “the state” means the institutions and bureaucracy that stay on when political leadership changes. The political leadership is called either “the regime” when we want to imply it’s evil or “the administration” or “the government” when we don’t. (I think this terminology is silly and “the regime” should mean the whole arrangement plus some other things--as in a regime of power--without negative or positive implications, but I don’t make the rules.)

Obviously these two things are not firewalled apart. Elected officials can alter the state through policy and/or direct reforms (creating, merging, or eliminating existing state organizations), and the existing state can constrain what elected officials can do through anything from ethics laws to bureaucratic foot-dragging. (In the US context, when we talk about “political appointees,” we mean high-level officials in “the state” that get appointed by elected leaders, but they take over organizations generally staffed by people who have come up through the bureaucracy and are supposed to be “apolitical,” i.e. just there to do a technical/bureaucratic job. So that’s another way that the two blur.) A great example of this would be what happened with the US’s Syria policy under Trump. Trump (”the administration”) wanted to pull out of Syria. The Pentagon, The State Department, various diplomatic branches, etc. (”the state”) did not. The state succeeded in putting him off executing his desired policy for years, even though as the Commander In Chief Trump in theory had really extensive authority to do whatever he wanted. Eventually he exercised that authority and state officials found themselves scrambling madly to try and salvage something of their preferred policy, which is how the US military ended up with this ridiculous non-presence in NE Syria. Another example would be the attempt to take down the USPS.

That’s why partisan politics and elected leaders are excluded from “the state” in this view; “the state” forms the organizational containers that those movements and individuals fill, and the structures they seek to act on or act from. You can think of it like the ground they stand on. This doesn’t have to mean it is itself “apolitical,” since the terrain has implications for everyone standing on it, but it is the object or delivery channel of politics, not politics itself. (Again I don’t agree with this, but it’s what you’re seeing reflected in the discourse you’re talking about.)

When people go on about “the deep state” they’re espousing a conspiratorial version of this view, where they think the ~real behind-the-scenes power lies in these institutions and the long-term bureaucrats who (sometimes) staff and run them. Definitely some power does lie there, but the conspiracists overweigh this into an Elders of Zion type thing.

2. A sovereign entity.

This is more about distinguishing states from other kinds of political entities, and as a result it’s less concerned with fine distinctions about what is and isn’t “political.” The idea is that there are lots of political structures and systems in the world (anything from tribal law to international associations like NATO) but not all of them are states. States are distinguished from other things by virtue of sovereignty. The classic definition (from Max Weber) of sovereignty is “a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence within a clearly bounded territory.” In other words, a state’s police, military, national guard, security forces, etc. have a license to use violence within its borders that no one else has--anyone else engaging in violence is a criminal. It is these groups’ status as “agents of the state” that grants them this license. The bordered, yes/no territorial nature of this status--Turkish security forces have no mandate to act in Greece and vice versa--is also distinctive; fixed, defined, cartographic borders are not necessarily a given. In this view, all power and indeed all law is ultimately founded in violence (enforcement), so what matters is who/what can use force with impunity. (When the state’s monopoly on force is challenged in its territory--e.g., Hizballah making war on Israel without the Lebanese army, the original Zapatistas forming a breakaway region during the Mexican Civil War, or any occupation by a foreign force--then the state’s sovereignty is “weakened” or “under attack,” etc.)

Lots of people have criticized and elaborated on this definition. I don’t want to go on forever about all the critiques that exist, but basically in reality, sovereignty is not a yes/no binary where either you have it completely or you don’t have it at all. Things tend to be more mixed and blurry. It also has more dimensions: two important examples are 1) controlling and disposing of the territory itself (exploiting natural resources, moving people around, etc.), and 2) recognition. In many cases, the difference between a state and a non-state is whether other states recognize it as such, i.e. act like it is one. So for example, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus exercises sovereignty and has a state bureaucracy, elections, etc., but because it is not recognized by ~the international community~ it isn’t “a state.” (This isn’t just semantics; it may seem arbitrary when you just think about what goes on inside the TRNC, but when its citizens try to emigrate, for example, they encounter very specific, concrete problems on this basis--e.g., their passports will not be recognized as valid.)

I find this more useful personally, especially because it doesn’t assume a liberal democratic state--it can apply to a dictatorship or a monarchy or whatever you like. But in practice, i.e. how people use it, I still think this approach is frequently too worried about pinning down differences that aren’t always useful. On the one hand, I wrote my BA thesis about how Hamas and Hizballah aren’t states (it was common for a while to refer to them as “states within states”) while also not just being political parties, terrorist organizations, service providers, or any of the other things they get tagged with, precisely because of the way they relate to the Palestinian and Lebanese states. This is worth understanding because it helps explain their political projects and their successes. On the other hand, I don’t think it’s very helpful to go around arguing that, say, ISIS was a state (or state-like) and the Houthis are not because of some detail of how they think/thought about territory, or courts, or bureaucracy. Like what do you get out of making that distinction. If you want to argue that a tribal council somewhere is “the state” for its context I think that’s fine depending on what you’re trying to get at. It all depends on what kind of question you want to answer, and on what scale.

3. There’s no such thing.

This view recognizes that the state is a salad bowl full of different organizations, individuals, ideologies, etc. that do not actually all work in lockstep together or have the same goals. To talk about “the state” is to reinforce the fallacy of unified power and cooperation. Instead, we should recognize that actors within states have their own agendas, institutional cultures, power struggles, etc., and that whatever the state does is the outcome of 1) these internal dynamics, 2) the ability of different external actors (from citizens to foreign governments) to play on/appeal to/push back against different pieces of the state, and 3) the interactions of 1 and 2.

This to me is common sense. You just have to be careful not to take it too far. We can acknowledge that the state is internally differentiated/not any one single thing without going so far away from what most people understand about their worlds. There’s no point saying “there’s no such thing as a state” when people still have to pay taxes.

4. "The state effect,” or: there both is and is not any such thing

This idea, put forward by Tim Mitchell, is my favorite. It is also the subtlest, and a little tricky to explain, but I think it’s the most useful.

This view steps back and looks at all the endless, elaborate debates about every possible nicety of “stateness” and says: perhaps we are asking the wrong question here. Maybe it doesn’t matter what the state is. Maybe it matters what the state seems to be; how it seems to be that; and what “resources of power” are generated by these impressions.

This is the tricky explanation part, so bear with me for a few paragraphs.

Where exactly do we draw the line between “the state” and “civil society”? Are NGOs and nonprofits part of the state? What if they get government funding? Especially in a neoliberal context, when so much policymaking is done through contractors, consultants, tax breaks, etc., are these kinds of organizations not carrying out the state’s agenda, consciously or otherwise? Okay, that’s tough, let’s try something easier: individual people and families aren’t the state. But if a household depends on an income from state employment, does that not affect their politics and their actions in society? Is a person “part of the state” in one building and not in another? How do we account for the way off-duty cops behave, for example, then? You can do this same exercise for “the economy” or any of the other things that are supposedly separate things/domains that the state manages. How can, e.g., the American economy be separate from the state when the state prints and guarantees the currency, sets interest rates, enforces contracts, and generally sets the terms on which the economy can exist? (Going back to your original question, you could probably also do this same exercise re: political parties, or partisanship.)

The point here is not that absolutely everything is actually the state. The point is also not that there is no state. It’s that there are not firm lines. Amazon may be the state when it builds systems for the Pentagon even though it is also, clearly, a private company and not part of the state’s institutions or subject to the same kinds of political controls that state institutions are. Similarly, the state itself is not one smooth solid object (as in #3). But it seems obvious, common sense, that “the economy” is a thing, just as “public health” is a thing, etc., and both of these things are objects of state management/governance/power.

This makes it easy for political leadership to make claims on the basis of these other things as separate “objects.” I.e., “we need to take drastic action to save the economy.” So the impression of these divisions can be used to justify or legitimate state action. You can see this super clearly in the current coronavirus situation. How many times have we been told the US has to “reopen” for “the economy,” and how many times has it been pointed out that the government could just take its own economic measures to allow people to stay home--because “the economy” is not some separate object that works by itself. (I myself had to explain to a friend that the government couldn’t just switch the economy back on by “reopening.” I think we underestimate how powerful these conceptual divisions really are in people’s understanding of how the world works.)

So, therefore, “the state” is the effect of ideas and practices that make things that political leaders and institutions do seem like they form a freestanding, separate structure, a thing, that we call “the state.” It is the ensemble of all these pieces (as noted in #3), and said pieces often include things that are generally thought of as not the state; these lines between state/nonstate shift all the time. What matters is not where the line is at any given moment but what the particular configuration allows state power (including the consideration of force from #2 and the structural concerns from #1) to do.

The problem I have with this is that it doesn’t really account for state capacity very well, but that’s for another day because I haven’t figured it out via paper-writing yet.

17 notes

·

View notes