#dsrv alvin

Text

20 YEAR DIVE-A-VERSARY

(I'm not old, YOU'RE old!)

copypasta from LiveJournal Dreamwidth:

Like Finding Nemo, Only Less Cartoony

Part III: 3955

On December 14, 2003, I went to the bottom of the ocean.

It is getting late in the Extreme 2003 cruise, and the handful of us on board who have not yet gotten the opportunity to dive on Alvin are starting to get worried. The electrochemists' instrument is giving so much trouble that the chief scientist is minded to send a member of their lab down on every dive in order to troubleshoot. This despite the fact that the instrument's daddy, D, has given a group of other scientists a course in running the instrument, and common fixes, so that we will be able to take in situ electrochemical readings on our dives despite not being well-versed in the field. Despite the fact that most of the electrochem failures have been due to hardware problems and instrument hard grounds which were unfixable from within the submarine and shut the instrument down for the dive after the point of no return. A few of the other PIs on the ship are looking out for those of us who haven't yet dove, however, keeping track of who had yet to dive and how many dives were left, dropping suggestions to the chief scientist whenever they feel they have a chance.

In all matters scientific on Atlantis, the chief scientist has final say. This includes selection of each and every scientific observer for each and every dive made on the expedition. S/He has, therefore, a very difficult job, coordinating the wants and needs of 20+ scientists (and their co-workers back home) with limited ship and sub time. There are naturally a lot of tensions. Our group has the added fun of a chief scientist who always waits until the last minute for things. The observers for a dive have generally not been chosen until the night before that dive; sometimes very soon before the night's dive briefing.

When you're a newbie scientist on Atlantis (and a huge Alvin fangurl to boot), you try so hard not to get your hopes up, and usually you fail. Even though I felt blessed merely to have the opportunity to be on the ship and do research at sea, and I knew there was no guarantee I would be able to dive on Alvin, I really, really wanted to be chosen. I couldn't help keeping track of how many newbies were aboard vs. how many total scientists got to dive vs. how many dives we had left [1]. All I could do was try to be helpful on board in any way I could (so I didn't seem like a waste of valuable ship-time expense), and hope.

After yet another yummy dinner [2] on Dec. 13, I am at the bank of computers in the Main Lab going over dive tapes for footage of Pompeii worm sampling. It is cold, frustrating work. iMovie keeps crashing, and the vagaries of the ship's environmental controls have made the main lab excessively air conditioned on this trip. (The annoyances are partially mitigated by being near the electrochemists' lab space. They were fun people and I enjoyed being with them.) At some point, the chief scientist, C, appears behind me, leans over my shoulder, and says quietly, "How would you like to dive tomorrow?"

…!!!

I think I squeak out a "really??!?!" whisper. C is suddenly the most awesome person in the world. (If I were chief scientist I'd get a huge kick out of making people's days/weeks/months/lifetimes by picking them to dive!) He reminds me when the briefing is (in a few hours!) and goes off about his stuff.

My attention span, naturally, is shot all to hell. I save my workspace and fly to the computer lab to send a squealy email (or what would have been squealy, if emails had sound) to advisor, mom, and boyfriend. I fly to my cabin and pull out the wool stuff I've brought for the occasion (socks, sweater borrowed from mother). I riffle through my file o' accumulated paperwork for stuff from the briefings I'd had earlier in the cruise. (Actually, I'm not really sure what I did before the briefing (besides the emailing and flying).) I am v. bouncy.

Apparently there is some shuffling about who's going to be diving with me. I get the feeling that P, who's finally chosen, is called to the briefing pretty much as it's starting and told just then. (did I mention C did things at the last minute?) C becomes even cooler: P is a newbie, too. C is trusting *two*newbies* with a full dive.

P and I are two newbies all ready to become Deep Sea Explorers.

What happens at a dive briefing? The chief scientist, observers, and pilot (minimally) meet and discuss the dive plan. Others may attend: the expedition leader (from the Alvin group), any scientists who have special equipment aboard or sampling requests. The dive plan is a list of objectives to be met for a dive, along with pertinent instructions, dive coordinates, sampling requests, etc. It's one of those things the chief scientist must rack his/her brain about every day. We also go over any instruments or equipment to be used, and the pilot or expedition leader will bring up any safety concerns or technical issues and make sure the dive plan is realistic given their capabilities. I learn how to operate the Sipper, the water sampling instrument that will be on Alvin's basket, which is controlled with a palmtop computer by one of the observers in the sub. We also get tips and reminders on note taking, video operation, what to pack for the dive, and much more.

After the briefing you pack up your warm clothes, notebook, dive plan, spare batteries for the palmtop, any goodies you feel like bringing (I'd brought a stash of Riesen for the cruise--chocolate can be like gold at sea) into a pillowcase which is stowed in a box in the Alvin hangar. The pilots will make sure your stuff gets in the sub when they prep in the morning. Then you try to get some sleep, as you're due on deck by 7am. I am afraid I won't sleep, but the darkness of my cabin and calm rocking of the ship work pretty well [3].

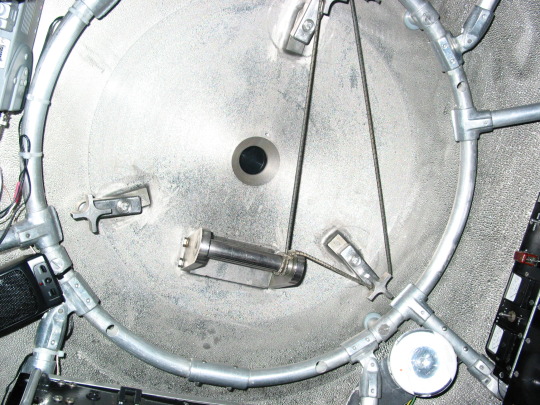

Regardless, I don't have difficulty getting up the morning of Dive 3955. ;-) The sun is not quite up when I get on deck. I snap a photo of one of the first sights to greet me, the expedition leader getting the sub ready for my dive. *g*

Expedition leader P prepares Alvin for my dive. Obviously he's a good leader, as he's managed to delegate well here.

The pilots and techs are working over Alvin, still in the hangar. I wander the deck and try not to explode with excitement. (B, the morning's launch coordinator, makes a comment to me about trying not to be nervous and going to get some coffee or something. I look nervous? I'm not; I'm thrilled! I'm about to ride the world's first deep-diving submarine to the bottom of the ocean! And there's no way I'm eating or drinking anything before being shut into a titanium sphere for 8 hours [4]!)

The dive plan, naturally, changes at the last minute, and we huddle to confer. Yes, I'm really short. From left, B (launch coordinator), C, T, P, and me. Behind B you can see the aft of Alvin; above our heads are some A-frame hydraulics. Also on the deck behind us are several float packs for elevators.

Preparations for the dive go mostly as usual. After what seems like the longest prep ever to get the sub attached to the A-frame, P and I are called up. We climb the stairs, remove our shoes, wave to the crowd.

P and I are ready to dive!

As the starboard observer, I enter first. There are designated places you're allowed to put your hands and feet, and you have to be careful on the way down not to trip switches (there are control panels everywhere in the ball, including just behind the ladder you climb down). The hatch opening is greased (to assure a tight seal, I assume) and you have to be careful not to hit that on your way in (I think I did, what with my gimpy knee--but we didn't leak or anything, so it's all good). The pilot is already inside. You fold yourself down into your space as quickly as you can so that the port observer can follow you down and get into his space. Once all three are situated, the launch coordinator removes the ladder and seals the hatch. There's no going back! (According to my research, no one's ever fainted inside the ball. You do go inside beforehand, during your dive safety briefing near the beginning of the cruise, and I reckon any claustrophobes are weeded out then--long before they're ever sealed inside.)

Inside the ball, it isn't as crowded as I expect it to be. (I think all three of us were on the small side.) I sit behind and to the right of the pilot, who sits on a padded box (the first aid kit, IIRC) behind his window, surrounded by controls. I have my own window, looking starboard and forward and a little down (it was actually a little low for comfort--when glued to my window, which was fairly often until we really started working, I was rather contorted). The windows are v. small; just wide enough for two eyes. If you have hands my size, and make a circle with your forefingers and thumbs together, it's about that big around. They are tapered with the wide end outside, so not only do you get a good range of vision, but I imagine it also helps the pressure issues. They're about 3.5 inches thick.

Above that is my little video monitor and the controls for it and for my pan-and-tilt camera on the top starboard of the sub. Each observer has a monitor that can toggle through every camera mounted on the sub (and there are a handful), and also a pan-and-tilt outside that's a camera + light that can be controlled by remote. You can also turn on or off overlays on your monitor, which give you real-time information from the sub's computer about temperature, depth, position, and much more. Two digital video recorders run throughout the sub's time on the bottom. One is slaved to the starboard pan-and-tilt (which also has two lasers on it that are fixed at 10cm apart so you can get a sense of scale), and the other is slaved to whatever the port observer has on his screen. So you have video responsibilities on top of everything else. There is also a tape recorder and mini-maglite in my little corner. Many things like this remind you that this ship has been in service (though constantly upgraded; there probably isn't a single original part left) since the early 60s, and things have evolved for utility through long experience.

To my left, in the back of the sphere, is the science rack, a big rack of equipment and stowage. (The observers also have racks above their heads holding computers and such--space inside the ball is at a premium.) A shelf there holds a few handheld digital cameras--video and still--for when the mood strikes us, as well as the Sipper's palmtop. There is also the all-important lunch, always packed [5]. In the corners between science rack and observers are oxygen tanks, CO2 scrubbers, your pillowcase full of stuff, oxygen masks, and other necessities.

You can, of course, see outside through your window even when the sub is still on deck; I admit to appropriating the digital camera (since I couldn't take my own) and taking lots of curiosity photos.

C aboard the Avon, as seen through my window as we dangle above the ocean waiting for the divers' signal.

Having watched a number of launches by this point, I know the drill, and it is interesting to actually be launched. I see a number of jellies outside my window as soon as we hit the water. I don't notice much about the final preparations; before I know it T is radioing Atlantis for permission to dive, and we are sinking silently beneath the waves.

I'm in that little sub!!

It takes about an hour and a half to drift 2500 meters to the ocean floor. After learning how early I was expected on deck, I had toyed with the idea of napping on the way down, but of course I'm way too excited for that. We use the time to go over the dive plan and make sure we're absolutely familiar with what needs to be done. The pilot spends the first few hundred meters checking for grounds in any of the electrical equipment. We also listen to music; yes, the pilots have installed a stereo system in the ball. And we get steadily colder. The ball isn't insulated, nor does it have internal heat. Ambient seawater is about 2° C (halfway between refrigerator temp and the freezing point of water). Hence the warm clothes. You're encouraged to wear natural fibers (think fire). They also supply a couple of wool blankets, neatly folded underneath the lunches below the science rack. My mom's sweater keeps me pretty cozy; my feet are a little chilly, as usual, so I am thankful for the blanket.

The hatch and its tiny one-eyeball window (T tells me it's to make sure we don't surface directly underneath a ship). You can just barely make out the seam. Note condensation on the ball, and audio speaker at bottom left.

With the cold comes condensation on the inside of the ball. You've sealed in air from the surface, which (because we were at 9° N) is warm and humid. So the inside of the ball gets quite wet. As the dive progresses, water starts to drip over your window, giving you a split-second moment of worry that it's leaking. (At the pressures of the deep sea--over 250 times atmospheric pressure--if there was a leak, you'd probably never notice it before the sphere was crushed, I reckon.) Water also collects in the bottom of the compartment (there is a flat floor inside the sphere over a little compartment beneath), so you're sitting in a puddle. I don't even notice my wet rear until we're ascending again; we are v. v. busy once we reach the bottom.

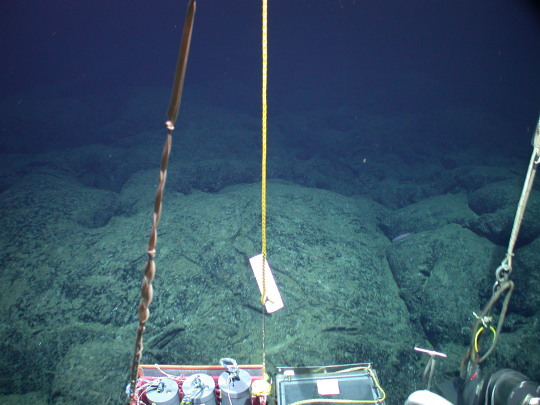

The seafloor, off-axis. This photo was taken by the Dancam, a high-res digital camera mounted on top of the sub that automatically takes a photo every 30 seconds during bottom time. The front edge of Alvin's sample basket is at bottom. At right, the starboard manipulator has taken hold of the elevator we will later attach to the InSECT. Look closely to see a sea cucumber.

Dive time is limited by the sub's battery power, so no external lights are switched on until we're just above the bottom. We're working on the East Pacific Rise, a crack in the ocean floor west of the Americas where hot water and sometimes magma oozes out of Terra's crust. The sub comes down off-axis, which means that it's a small distance away from the vent area. You don't want to come down right on top of one of those black smokers!

Before we discovered vents (off the Galapagos in 1977), we thought the deep sea was a pretty barren place, biologically speaking. If you consider the common method of deep-sea biological sampling--tow a net behind your ship--it's no wonder. (One oceanographer remarked that sampling the deep sea was like running blindfolded through a field with a butterfly net above your head.) Hydrothermal vents are probably the primary focus of deep sea life, and they are *packed*. Some figures place the biomass per unit volume at a vent as much higher than the "photic zone" where light penetrates the top of the ocean. That's saying quite a lot, especially considering that we were under the impression that all life on Terra somehow traces its energy back to the sun; there is no sunlight on the bottom of the ocean.

So we reach the bottom, 2502 meters below the surface, off-axis where there isn't a lot to see. Mostly flat rocks (pillow basalt) and a few sparse pink sea cucumbers and sea stars. T gets his bearings (based on the baseline established by Atlantis once arriving on station), and drives us toward the vents. The best indicator that you are approaching the vent area is the crabs. There are little white crabs everywhere down there, and they increase in density as you move closer to the hot water, where everything else thrives. Regardless, the bottom of the ocean is an entirely different world, with plenty of strange alien life.

Another thing that increases in density near the vents (but mostly off-axis) are "Alvin droppings": scores of dive weights left where they're dropped to rust and return to the ecosystem. ;-)

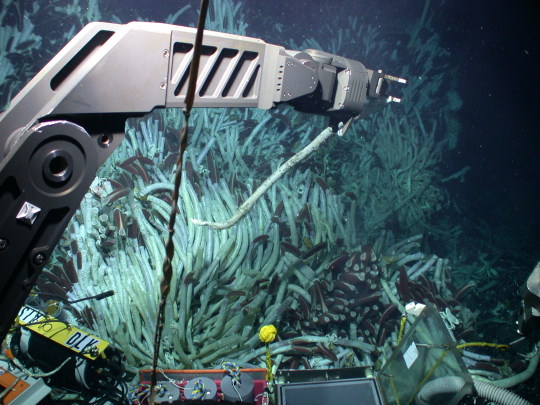

Most of our work is at a place called Tica. This isn't actually a black smoker, but an area of diffuse flow--great habitat for Riftia, the giant tube worm. We retrieve the electrochemists' InSECT (In Situ ElectroChemical Tool, named on this cruise by one of the pilots and looking a little like a mantis), sending it to the surface on an elevator. We sample the Riftia around which the InSECT has been taking measurements for the past four days. We pick up numerous sampling devices that have been set down there at the beginning of the expedition. We take a water sample with a niskin bottle that had been rigged atop the sub; the rope to trigger it is flippantly labeled "Pull to Flush." (hee!) My window isn't well situated to observe the action in front of the sub, so I mostly watch my monitor (at one point my pan-and-tilt is right on the action, because the pilot wants to use its lasers to mark the area he's working in) and work the Sipper. Tica is an incredible place; giant tube worms growing in clumps almost like flowers, their red lipstick-shaped gills poking out of their tubes. Older clumps of Riftia are tangled masses. Swarms of amphipods above the worms like insects. Crabs crawling over and under and around--the worms go down in their tubes when poked, a likely crab-defense-mechanism. The occasional ghostly white eel-like fish.

Taking a sample of a giant tube worm. The pilot honestly just grabs the tube in a manip and pulls it up like a weed. It will go in the open biobox on the basket. The InSECT is at bottom left.

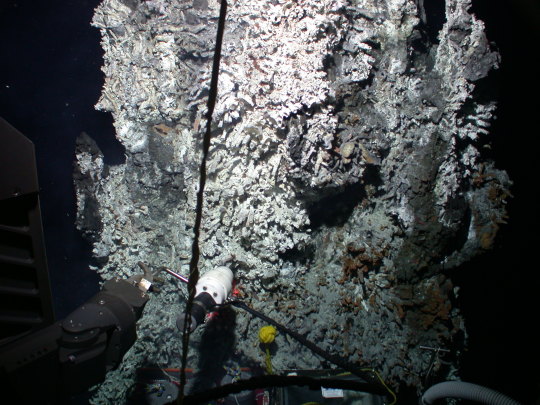

After finishing our sampling at Tica and moving slightly off-axis to send the InSECT up, we drive to an actual black smoker called Q Vent. Driving is one of the biggest drains of battery power for Alvin, and our driving around to find the elevator for the InSECT, find various samples, and find Q Vent, coupled with a less-than-optimal battery charge [6], cuts our dive time short. After a cursory survey of a portion of the Q Vent chimney where my organism of interest, Alvinella pompejana, is growing, T informs us that we have only 40 minutes remaining on the bottom due to power concerns.

Taking Sipper samples of an alvinella colony at the Q Vent. The Pompeii worms grow in papery tubes of metal sulfide directly on the sides of the chimney. The instrument being held in a tube here has a temperature probe and electrodes for electrochemistry (when it's working), as well as the inlet for the Sipper. Note the red dots of the starboard pan-and-tilt's lasers, which are 10cm apart for scale.

One the things about which I'm most proud, being on a double-newbie dive, was the decision we made at that point. With 40 minutes, I felt there was no way we'd get any appreciably good Alvinella samples--both my group and the bacterial group are interested in well-documented measurements before sampling, especially of temperature and electrochem. Rather than doing a quick snatch of random worms, we decide to abandon the colony and get a frying pan set up in the time we have remaining. A frying pan is an apparatus our geochemists have built to put over the top of a vent chimney to grow a "protochimney." A day or so after placement, the frying pan is collected and brought to the surface, where it can be dissected to find out what's in a growing chimney [7]. We have just enough time to take Sipper samples of the black smoker on top of Q vent (which is a very tall chimney) and place the frying pan before we run too close to our power reserves.

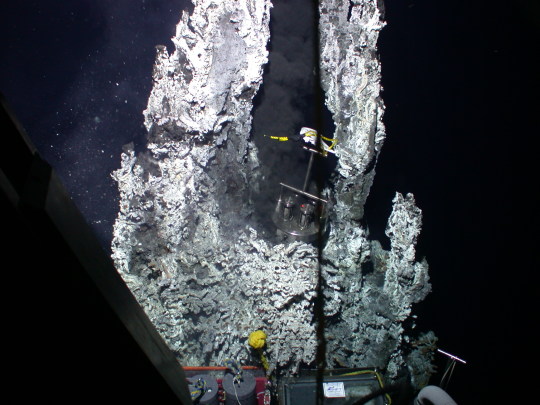

The frying pan placed atop Q vent. The "smoke" isn't actually smoke, but metal sulfides precipitating out as they hit the cold seawater. These precipitates are what build the chimney at a hydrothermal vent. The water at the vent opening is 350° C (3.5 times the boiling point of water). It doesn't boil because of the extreme pressure. Note the "snow" in the water all around; these are clumps of bacteria.

Having accomplished all that we could for the day, we drive slightly off-axis and drop weights, beginning our slow float to the surface. All the exterior lights are again extinguished and the only thing to be seen outside our thick Plexiglas is occasional little specks of bioluminescence.

What the bottom of the ocean *really* looks like.

On the way up, there are still tasks remaining. The pilot has things to take care of with the sub and its computer.

T, our pilot, types data into Alvin's computer.

We scientists collate our notes and prepare a science report, which is called up to the surface once those up top are ready for it. The science report is a quick summary of what was accomplished on the dive, generally received and/or circulated during the afternoon science meeting. It's useful for the rest of the team on the surface to know what samples and how many are on their way, so that preparations to receive them can be made. The obligatory "this is me in the sub!" photos are taken. And we finally have time to eat lunch!!

P in the port observer's position, readying the science report. Yes, they've put in some cushions between us and the titanium, thank goodness. His window is just behind T's knee; you can see the blue pad around it.

Me, sitting in the pilot's seat. Behind me on the control panel you can read the temperature (in green), 1.8° C, and the depth (in red), 1559.4 meters.

I have yet to write in detail here about recovery, but one thing that happens is that Alvin sits on the surface for about half an hour which Atlantis slowly and carefully drives up to it and gets into position for recovery. Alvin is a fairly small boat--about the size of a UPS delivery truck--and so even calm seas will move it around quite a bit, in various directions. Waiting for recovery was one of the few times during the expedition that I felt seasick. I closed my eyes and took deep breaths, telling myself in firm tones that I Would Not Be Sick.

I'm sure the scientists aboard had a great time planning for not one, but two initiations once P and I returned from the ocean floor. (another planned entry--initiations!) Actually, I know they did. After we climb out of the ball and stretch, we look for our shoes; they aren't in the bag on the side of the A-frame where they've been left. G, the recovery coordinator, points them out: sitting on the yellow line delineating the "safe" zone, mine frozen in a block of ice! (P's are merely frosty from being in a freezer.) I nearly fall off the stairs on my way down from laughing so hard! We're duly initiated, and I set my icy shoes out of the way to thaw and dry in the warm equatorial afternoon sun.

Some cold shoes. Compared to the stories I've heard, this was a pretty mild prank!

I'm very amused. :o)

Since we haven't gotten any Alvinella samples (disappointingly), I don't actually need to be present for the daily basket-swarming. I hang around in the sunshine drying off until P chases me off the deck because I'm not wearing shoes. (Um, obviously.) That's my cue to squelch my way inside and downstairs to change clothes.

The evening of that memorable day is also notable. I wander a good deal, winding down from my incredible experience. Out on the deck, seaman E is shining a light overboard and is fishing for squid amidst swarms of silvery flying fish [8]. If you discount most of 'em being underwater, they look quite a bit like a flock of little birds. I watch E help B bring in one of the biggest catches of the cruise.

B and his mondo squid. [9]

Finally I go looking for a flashlight so I can go up to the bow and look at the stars. D, one of the SSSGs, offers to go with me. We plant ourselves on the deck in the bow and cast our eyes to a glorious night sky spread above us. I've only seen that many stars before on camping trips in the mountains of Idaho. And it was somehow fitting to end a day spent at the bottom of the ocean by exploring the vast heavens.

Note: if I haven't done so before, I heartily recommend the book Water Baby by Victoria Kaharl for any and all fans of Alvin. It's out of print, so look for it at your library or used. It's a fascinating history of science and discovery.

[1]: Then there are the additional considerations: every eighth dive is a PiT dive, where the sub carries a pilot-in-training in place of one of the two scientific observers aboard. Also, it was general practice (at least on our cruise) that at least one of the two scientific observers on a dive was "experienced" (has been down at least once before).

[2]: The food aboard Atlantis is v. good. Our steward/cook, L, was amazing. At our very first briefing on the ship, the captain told us we *would* put on weight during the cruise.

[3]: I slept really well on the ship. The only time I didn't was when we had weather. My cabin was a level below water level, up in the bow. Waves of any appreciable size would SLAM into the hull with resounding booms. When we were cruising or there was weather, it was a little like being inside a cannon.

[4]: Indeed, Alvin has no restroom. They do carry bottles for necessity. You have to empty your own up top if you used it. You can well imagine the apparatus is much easier for males to use. I managed to not need it.

[5]: The one time Alvin was wrecked (it fell off its cradle during a launch in 1968 and sank--no one was inside), it stayed on the bottom of the ocean for nearly a year with its hatch open. After the salvage, they found the lunches inside incredibly preserved by the cold of the deep sea.

[6]: You know how your Walkman's rechargeable batteries will charge better if they're completely drained beforehand? The principle is the same for large batteries, too. The night after 3955, the Alvin group deep-cycled the batteries. There was no power shortage on the next dive. I'd be bitter, but really I'd have been happy and fulfilled with a scant five minutes on the bottom.

[7]: The downside here is that 3955 ended up being our last dive in that area, so that frying pan we put there was never recovered and is probably now a part of Q Vent. I still think we made a good decision. I imagine a lot of sampling devices get left and are overgrown (biologically or geologically) down there. Vent ecosystems are extremely dynamic.

[8]: I only saw the flying fish at night, usually when E was fishing or when we had a light out there for a CTD cast (ack, another entry: CTD hooking!).

[9]: We grilled it (and others) at the end-of-cruise barbecue!

#i still kinda can't believe this happened to me#also sign me up to dive in the new sphere#(please please please)#dsrv alvin#extreme2003#deep sea research#r/v atlantis#science#deep sea#alvin

1 note

·

View note