#even if that scholastic book fair series is very well written and has War Crimes

Text

hi besties! I was too young to experience it as it came out and could never seem to find enough of the books in sequential order at school for me to start reading them but apparently they're on the internet for free now.

so.

should I read Animorphs?

#animorphs#i guess?#I've been stuck in the remnants of my interest in the World's Worst Fandom for a while now and want to branch out#but part of my brain is Extremely Averse to reading scholastic book fair books in senior year of high school#even if that scholastic book fair series is very well written and has War Crimes

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

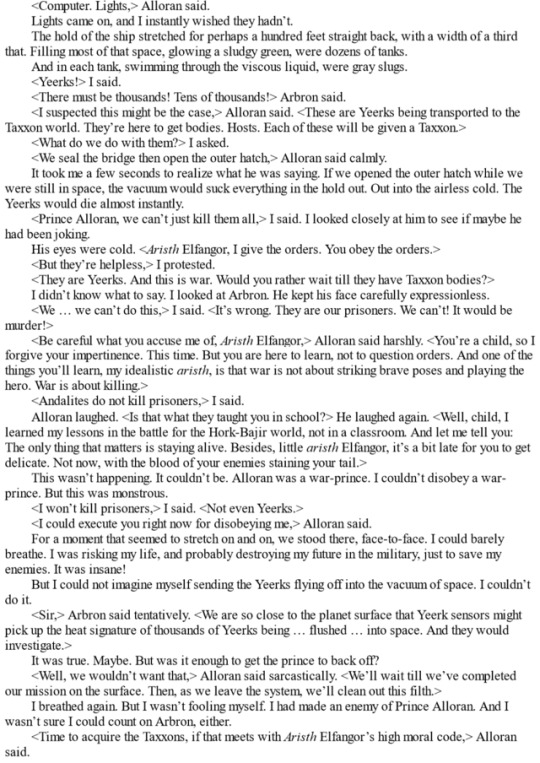

This---this right here. This is why I love Animorphs.

Specifically, this is from The Andalite Chronicles, which was written during the series’ run, but serves as a prequel to the series as a whole (but, according to the reading order I have, is slotted in between books twelve and thirteen). Regardless, it’s part of the Animorphs series, and honestly, talk of andalites and yeerks and the presence of characters like Elfangor and Alloran aside, you can really, really tell thanks to conversations like this.

In so many fantasy and sci-fi stories, there is a clear dichotomy between those who are Good and those who are Evil. Those who are Good are the protagonists, whom you root for; you celebrate their victories, you cry for their losses, and you excuse what they do because they are Good and therefore they are Right. Meanwhile, those who are Evil are those who are the antagonists, whom you despise. You fear their victories, you celebrate their losses, and you know that no matter what they ado, they are Evil, and therefore they are Wrong. Even if the Good characters end up doing the very same things as the Evil characters, so long as the Good characters are doing those things to the Evil characters, you are never meant to question, doubt, or criticize them. They certainly aren’t made to question, doubt, or criticize themselves. The narrative never questions or criticizes their actions or decisions. At best, their behavior---which in some cases may amount to war crimes---is ignored. At worst, it’s celebrated.

Take, for example, the world-renowned Harry Potter series.

(And obligatory disclaimer right here: I am a longtime Harry Potter fan, I really love Harry Potter, and I am not trying to bash Harry Potter by using it as an example here, so please don’t get it twisted to start wank, thank you.)

Harry Potter is another children’s literature series about war. People die in Harry Potter, as they do in war. People are tortured in Harry Potter, as they are in war. The main characters, children that they are, are tortured at a couple different points. They lose loved ones. People are disfigured. Children are left orphans, and so on and so forth. It’s a story about war, and these things happen in war.

But what’s relevant to this particular post is that some of the protagonists, over the course of the war, end up committing a few war crimes of their own as defined by the laws of the fictional universe in which they reside. In particular, I’m talking about their use of what in their universe are known as the Unforgivable Curses.

In Harry Potter, as you may know, there are three spells that are considered Unforgivable and are therefore illegal. They are Avada Kedavra, the killing curse; Imperio, a mind control curse; and Crucio, a torture curse. Beginning in book #5, Harry shows a willingness to use these curses when he attempts to use Crucio on the woman who murdered his godfather right in front of him. He fails at using it, yes, but he tried. And whether Harry’s feelings and actions actually were justified or not in that moment is not really the point I’m trying to make here. The point I’m trying to make here is that Harry himself never thought about it. Now, to be fair to Harry, he was going through a lot at the moment; Order of the Phoenix is easily the best book in the Harry Potter series because Harry was realistically written as a traumatized teenage boy, which in all honesty we don’t see as much as we should in the other books. Nonetheless, Harry, to my recollection, doesn’t spare much (if any) thought to it, until he uses the curse again in book seven, and actually succeeds, all because he saw one of his favorite teachers be spat upon. (Which, to me, was alwasy rather illogical, like . . . he can’t muster up the will to torture when his godfather is murdered right in front of him, but he can when his favorite teacher gets spat on? OK.) And while said teacher is aghast that he used the curse, once Harry explains that it was because the one whom he cursed had spat on her, she gets flustered and we’re supposed to take it as a touching moment. It isn’t brought up again after that.

Now, again, to be clear: Whether Harry was actually morally fine with using an Unforgivable Curse in that moment is not the point of this post. My point is that no one in the narrative questioned it. Using Unforgivable Curses liberally, for small offenses, is what the villains of the story, the Death Eaters, do. Those curses are unforgivable for a reason. Those curses are illegal for a reason. Using them amounts to war crimes. Yet the protagonists use Crucio and Imperio to achieve their ends, just as the Death Eaters do. And, yes, all right, this is war . . . but if the morality of doing so is brought up, it’s dismissed a paragraph or two later. Harry never considers what it says about him that he’s willing to torture because someone he likes was spat on. He doesn’t consider how easily he’s pushed to violence, how far he’s willing to go. He doesn’t question whether this war is turning---or has turned---him into something perhaps he doesn’t want to be turned into. In Harry Potter, questions of morality begin and end at goals; what defines the Good Guys and the Bad Guys is what each side is fighting for---which, to be fair, is rather easily done in Harry Potter, given that the Bad Guys want genocide. Make no mistake, the Death Eaters were legitimately Evil and wholly in the wrong, the protagonists were wholly in the right to stop them, and I would NEVER suggest otherwise. But, from a realistic standpoint, tactics matter, too. Things like torture and murder shouldn’t be excusable simply because you’re the Good Guys. How good are you, really, if you’re willing to torture and murder---if you don’t feel even an ounce of guilt over it? How good are you when, from the perspective of your enemy, you might be the Bad Guys, while they’re the Good? That wasn’t the case in Harry Potter---again, the lines of Good and Evil were very clearly defined---but in many (if not most) real life wars, it is.

Don’t misunderstand, Harry Potter is not alone in this. Many, if not most, fantasy and sci-fi stories stop at the question of goals and leave it at that, particularly when those stories are aimed at children. They don’t question tactics within their narratives, and they don’t make their protagonists question their tactics. They don’t make their protagonists take long, hard looks at themselves, nor do they make them quarrel with each other over what is acceptable and what isn’t.

But Animorphs does, and I love that.

In Animorphs, the lines are very clearly drawn in the beginning, and to be honest, a lot of the assumptions made in the beginning are correct, at least insofar as the Yeerk Empire goes. The Yeerk Empire is corrupt, evil, and wrong; they enslave, slaughter, and destroy. They must be stopped, just as the Death Eaters had to be stopped in Harry Potter, and that is inarguable. However, just because the yeerks (at least insofar as the Empire is concerned; we’re setting aside the Yeerk Peace Movement at the moment for sake of simplicity) were evil, the series makes it clear that this does not mean that every single tactic used against them is justified. As seen above, when Alloran wants to slaughter tens of thousands of defenseless yeerks---prisoners that are at his mercy---Elfangor steps up to argue with him, despite being a far lower rank, despite being a complete newbie on the battlefield. From the perspective of Alloran, Elfangor, and Arbron, the andalites are the Good Guys. The yeerks are the Bad Guys. This means, in Alloran’s opinion, that whatever they do is perfectly fine and justified. But Elfangor, who recognizes that the yeerks are still sapient beings even if they are the enemy (and are Evil), feels that their tactics still need to be called into question. He argues, because from a moral standpoint he doesn’t feel that it’s justified to murder defenseless prisoners of war simply because it’s a war and because they can.

And that’s what makes Animorphs so great.

Animorphs is not afraid to breach these topics. This is a sci-fi series that was aimed at children. It was published by Scholastic. And it told the story of a war that was, for the vast majority of the series, fought by a group of children using guerilla tactics against an Empire far larger than them. And it tackled these issues. The Chronicles books were arguably written for a slightly older audience, given that they were longer, but you cannot tell me that the author and publishing company did not know there was a very high probability that the children who read the main series would read these ones, too. And even outside of the Chronicles books, the main series tackled these issues as well. The Animorphs and Ax consistently, book after book, got into arguments with each other and themselves over the tactics they used in the war. They decided early on that there were some lines they would not cross because they did not want their tactics to make them sink to the levels of their enemies. And when the time came later when the war forced them to cross those lines (as much as those with free will are forced, and as war does), they still acknowledged that, with themselves and with each other. They struggled to make peace with it. Some of them never succeeded.

And the best part of all of this is that if you read the passage above, the narrative does not tell you who you should side with. You might think that you should side with Elfangor, since the book is in his perspective; but the narrative doesn’t paint Alloran as a cold, heartless murderer, in my opinion. It shows him as a seasoned, hardened, traumatized (given information earlier in the book) war veteran who has experienced far more than Elfangor has, who perhaps knows more than he does. Alloran is not arguing for the execution of the yeerks here because he wishes to see them die, or because he wants glory; in fact, he specifically says that war is not about glory. He’s arguing for their execution because he feels it’s necessary given the circumstances they’re in with regards to the war. This doesn’t mean that he’s right. His experience doesn’t make him right. However, Elfangor’s morality also doesn’t necessarily make him right. The narrative leaves up to the reader to decide for themselves who they think is right in this passage, and that was intentional. Applegate once said that, while writing, she challenged readers “again and again to think about right and wrong, not just who beat who.” Animorphs raises these questions, with the characters and with the readers. Animorphs is a war story questions its characters not just on their goals, but on their tactics, and acknowledges the fact that being the Good Guys doesn’t mean you get to do whatever you want with impunity. Or at the very least, that it shouldn’t mean that you get to do whatever you want with impunity.

And that’s why I really, really love Animorphs.

#animorphs#the andalite chronicles#elfangor sirinial shamtul#alloran#arbron#mmmmm honestly tho call me when a certain sci-fi series about giant cat-shaped mechas would ever#because they had the perfect opportunity in 5x02 to do this but bad writing made them pass it up#and make all their protagonists sans sir not appearing in that episode appear terrible as a result#ho hum. guess they can't all be animorphs huh#meta

25 notes

·

View notes