#fergus mac leti

Text

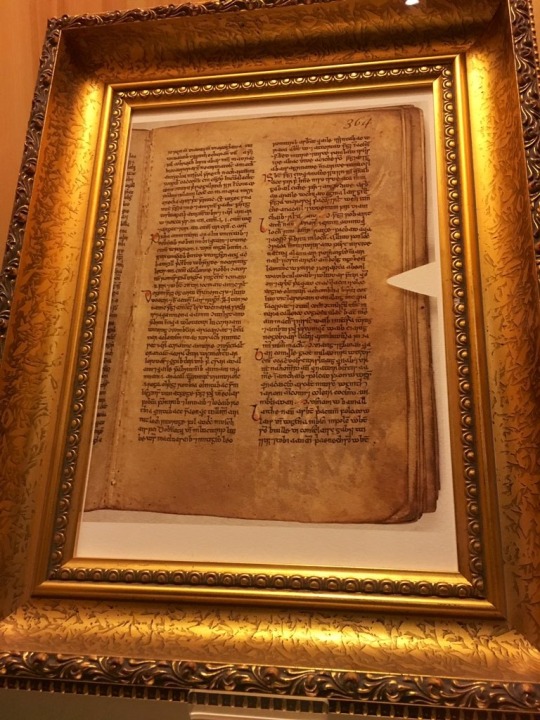

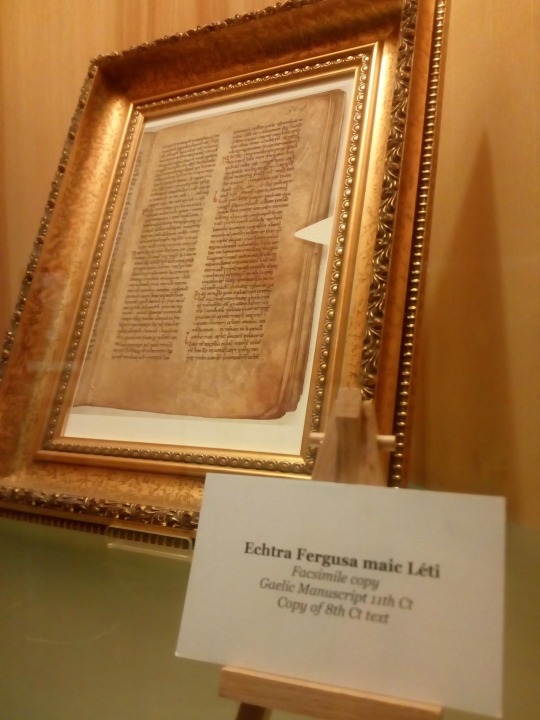

Echtra Fergus mac Léti facsimile copy Gaelic manuscript 11th Ct - Copy of 8th Ct text

"This medieval tale "Echtra Fergus mac Léti" (Saga of Fergus son of Léti) contains the earliest known reference to a leprechaun (8th Century). This facsimile copy is on display in Ireland's National Leprechaun Museum."

-taken from @nicolekearney & @leprechaun_ie on twitter

https://paganimagevault.blogspot.com/2022/03/echtra-fergus-mac-leti-facsimile-copy.html

#leprachaun#st patricks day#fergus mac leti#manuscript#ireland#irish#celtic#history#pagan#paganism#europe#antiquities#museums#literature#middle ages#medieval literature#gaelic#11th century#8th century

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leprechauns, The Mythical Creatures of Irish Folklore and Their Story

In 2010, a special team from the European Union’s European Habitats Directive commission traveled to the Slieve Foy Mountain in Ireland’s Cooley Peninsula to make a very special and very unusual announcement. The Sliabh Foy Loop trail in the forested area was to receive special protection under EU law, designed to protect the habitat of its native residents: Leprechauns.

The Irish leprechaun had received an elevation of status from being a purely mythical creature to being recognized as an official species by the European Union. Perhaps that was the start of the process that led to Brexit?

Either way, the legend of the leprechaun was given a new lease on life after decades of depictions in the media often seen by the Irish as obtusely derogatory.

The Leprechaun – A ‘Little’ Backstory

The legend of the leprechaun is perhaps one of the most authentically-Irish of stories that has ever been told. The short stature, red beard, green waistcoat, green breeches and the all-important tall, green top hat have become virtually synonymous with the Emerald Isle and its people.

But how much of what we think we know about the Irish leprechaun is true and how many presumptions are fallacies or convenient, racist descriptions perpetuated by money-hungry Hollywood?

Is the pot of gold part of the original myth? Can the story of the red beard be traced back faithfully? How about the green clothes? Surely, they have not been made up… right?

One of those three features that we unfailingly associate with the Irish leprechaun is, sadly, a modern-day construct. Take a moment to consider which of them you believe is the culprit, and find out if the luck of the Irish rubbed off on your guess as we delve into the history of this fascinating creature.

The Origin of the Leprechaun Name

There is no single source name which can be wholly attributed the honor of being the root of the modern English word, ‘leprechaun’.

The Irish word ‘leipreachan’ is thought to come from the Old Irish name, ‘luchropan’, which is a combination of ‘lu’ (small) and ‘corp’ (body). Alternatively, ‘leithbragan’ also exists in Irish, and it is an amalgamation of ‘leith’ (half) and ‘brog’ (brogue), which alludes to the common portrayal of the leprechaun as repairing a single shoe.

The leprechaun has also been known as the lepreehawn, lioprachan, leprehaun and lubrican. The last of these was the first allusion to the mythical creature in the English language and was first used in 1604 by the poet, Thomas Dekker.

The Irish Leprechaun in Legend

It was in the 14th century that the book, Echtra Fergus mac Léti (Adventure of Fergus, Son of Leti) was written. It is this volume that is cited as the debut of the leprechaun on the literary world.

The Character of the Leprechaun

In that book, the protagonist has fallen asleep by the sea when he is woken by the sensation of being dragged towards the water. He wakes and seizes the three diminutive sea sprites that are attempting to drown him.

This anarchy-laced edge to the leprechaun’s character is a common theme that runs in many of the stories about them. In most versions, that trait is shown as more of a roguish propensity toward mischief and trickery rather than the homicidal intent of the original story.

Author and expert on Irish folklore, David Russell McAnally, states that the leprechaun is the offspring of an “evil spirit” and a “degenerate fairy” and is “not wholly good nor wholly evil”.

Another account, found in the book, ‘A History of Irish Fairies’, suggests that they were the “defective children” of fairies whose appearance and disposition made the outcasts from that society.

The tale of Fergus, son of Leti, also introduces another important element of the leprechaun legend – that they will grant three wishes to the person who captures them. Fergus is granted the boon and one of the gifts he asks for is the ability to breathe underwater.

Through other myths and legends passed down from the Irish storytellers of yore, we know that leprechauns love their solitude. That does seem to be a departure from the rampaging trio mentioned in Fergus’s adventures cited above, though.

On the other hand, a leprechaun’s solitary existence does not bar him from his love of a good time. It is said that they are happiest when dancing and will find any excuse to gulp down some ale and indulge in a lively jig.

The Leprechaun’s Pot of Gold

Perhaps the most popular element of the leprechaun’s tale relates to his pot of gold. Leprechaun legends say that these creatures stow away the golden treasures they have collected through the ages in little pots.

The award-winning Irish poet, William Butler Yeats, said that this bounty was not earned by the leprechauns but came from uncovered caches found buried in the ground, and dated back to times of conflict. These pots were then buried in remote spots and only the leprechaun who buried it knows its location.

There is one exception, though; when a rainbow forms, its ends touch the earth where the pots of gold are buried. That is where the myth of finding a pot of gold at the end of a rainbow originates.

Leprechauns and Shoes

Rather at odds with the tale of the riches is the fact that leprechauns are often depicted as shoemakers or menders. It is said that it is the sound of the tiny hammers beating little nails into the soles of shoes that alerts you to their presence.

However, locating a leprechaun even with the sound of the hammer to guide you is said to be a nigh impossible task.

Why are leprechauns so obsessed and adept at mending shoes? Well, that has to do with their love of dance. Apparently, their frequent and fervent bouts of dance wear away the poor soles of their tiny dancing shoes and every leprechaun is constantly preparing his footwear for when the next urge to break out in an energetic effusion of energy hits.

The Leprechaun’s Appearance

The leprechaun has always been depicted as a diminutive character. He is always male, often red-haired and is more likely than not to sport a red beard, too.

While the first mention of the Irish leprechaun suggest that they are associated with the sea, the majority of Irish myths and legends tell us that the elusivee creatures live in wooded areas, sometimes in caves and even in gardens.

These characterizations of the Irish leprechaun are faithful to the original tales from the Eire.

What Clothes Do Leprechaun’s Wear?

Don’t feel too bad if you didn’t know that the Irish leprechaun originally did not wear a green outfit but a red one; almost no one realizes that fact until they do a little research themselves!

Acclaimed author and Irish folklorist, David Russell McAnally, describes the leprechaun as a figure about three feet high, clad in a red jacket with an Elizabethan ruff at the neck. He is clothed in red breeches that are buckled at the knees and below that, the creature wears stockings which are either gray or black in color.

McAnally goes on to describe the leprechaun’s hat as worn cocked in a style common in the 19th century. He also says that the leprechaun wears a frieze overcoat in the rainy season that allows it to camouflage itself into the background so well that you would be unable to located it unless you espied the cocked hat.

William Allingham wrote in the 1700s that leprechauns appeared elderly, wizened and bearded. On their noses rest eye glasses and they wear silver buckles on their hose. A leather apron and a partially-repaired shoe completes the ensemble.

Samuel Lover described the leprechaun in 1831 as wearing a red square-cut coat that is richly embroidered with gold thread, together with a cocked hat, shoes and buckles.

When Yeats had an opportunity to indulge in the history of this legend of his native land, he stated that there were two types of fairies; solitary ones like the leprechaun and those that lived in groups. The former wore red jackets and the latter wore green.

He further described the red jacket of the leprechaun as having seven rows and seven columns of buttons. Yeats’s leprechaun had the uncanny ability to balance himself upside-down on the tip of his pointed hat and spin around about that point. He also made particular mention of its inclination towards mischief.

As you can see, there is only general consensus between the various versions of the leprechaun’s clothing that experts on Irish legends have left us. There is also the matter of geography, at least according to McAnally.

He wrote that the native leprechauns of the four different regions – the North, Tipperary, Kerry and Monaghan – could be distinguished by the color of their accoutrements and the objects that they carried with them.

Logheryman leprechauns were from the North and wore a red military coat above white breeches. They shared with Yeats’s creature the love of standing upside-down on their pointed hats, which McAnally described as high and wide-brimmed.

Tipperary was home to the Lurigadawne leprechaun, known for its red jacket of antique design that had peaks all around. This leprechaun brandished a sword that could also double as a magic wand.

The Luricawne leprechauns of Kerry were cheerful individuals with faces so torrid that they matched their red jackets. They donned cutaway jackets which had seven rows of seven buttons each.

In Monaghan, you would find the Cluricawne leprechaun who wore a green vest underneath an evening coat with swallow tails. White breeches, black stockings and shiny shoes completed the lower half of the outfit. On his head would be a cone-shaped, brimless hat which could double as a weapon.

Leprechauns in Popular Culture

Hollywood has been at it again, exploiting race and perpetuating stereotypes in the search of a quick buck. The Irish diaspora has long complained that their depiction in the media is nothing short of a series of caricatures and racist simplifications.

Perhaps no single part of the problem bears greater blame than the depiction of the Irish leprechaun.

The Leprechaun in Film

You would have been hard-pressed to find a film where a leprechaun was the main character (and the title character) before 1993. That year, the film, Leprechaun, starring Warwick Davis was released.

Featuring the mythical Irish creature as a murderous, rampaging maniac, it performed surprisingly well at the box office, taking in almost $9 million in ticket sales against a budget of under $1 million. Despite the fact that it performed well, the film that was Jennifer Aniston’s debut on the big screen was severely panned by critics and even deemed to be the worst performance of Aniston’s career.

It cast dwarf actor, Warwick Davis, in the starring role. Davis was fresh from his success as the Ewok, Wicket, in George Lucas’s Star Wars Episode VI: Return of the Jedi, as well as major roles in the hit films Labyrinth and Willow.

Davis reprised his role for all five sequels, the latest of which was released 10 years after the original in 2003.

The Leprechaun on the Small Screen

The controversial American TV series, American Gods, has been regaling audiences with distorted versions of myth and religion for one season now, and has been renewed for another season next year.

The storyline follows the ‘Old Gods’ – those that have been worshipped in mankind’s ancient and recent past – as they struggle for the attention and reverence of today’s generation whose gods have become technology and the media. Among the ancient magical creatures that make their presence felt in the new world is Mad Sweeney, a leprechaun.

Mad Sweeney was a character from Irish lore who was not actually a leprechaun but a king cursed to wander the world in isolation and madness until he is killed by a spear. The American Gods version of the character is a leprechaun.

He is played by Canadian actor, Pablo Schreiber.

The post Leprechauns, The Mythical Creatures of Irish Folklore and Their Story appeared first on Ragnar Lothbrok, Lagertha, Rollo, Vikings, Ouroboros, Symbols and Meanings.

Source: http://mythologian.net/leprechauns-mythical-creatures-irish-folklore-story/

0 notes

Text

The King and Queen of the Leprechauns

This week I look at the saga of Fergus mac Leti, which some scholars believe contains the oldest known mention of leprechauns.

Read more

0 notes

Text

Fergus goes down into the lake by Stephen Reid 1910

"Fergus mac Léti (also mac Léte, mac Léide, mac Leda) was, according to Irish legend and traditional history, a king of Ulster. His place in the traditional chronology is not certain - according to some sources, he was a contemporary of the High King Conn of the Hundred Battles, in others of Lugaid Luaigne, Congal Cláiringnech, Dui Dallta Dedad and Fachtna Fáthach.

According to the Caithréim Conghail Cláiringhnigh (Martial Career of Congal Cláiringnech), while Lugaid Luaigne was High King of Ireland, Fergus ruled the southern half of Ulster while Congal Cláiringnech ruled the northern half. The Ulaid objected to having two kings, and the High King was asked to judge which of them should be sole ruler of the province. Lugaid chose Fergus, and gave him his daughter Findabair in marriage. Congal refused to accept this and declared war. After trying and failing to overthrow Fergus, he marched on Tara and defeated and beheaded Lugaid in battle. Installing himself as High King, he deposed Fergus as king of Ulster, putting his own brother Ross Ruad in his place. In the reign of Fachtna Fáthach, Ross was killed in the Battle of Lough Foyle, and Fergus was made king of Ulster again.

In the Saga of Fergus mac Léti, he encounters water-sprites called lúchorpáin or "little bodies"; this is thought to be the earliest known references to leprechauns. The creatures try to drag Fergus into the sea while he is asleep, but the cold water wakes him and he seizes them. In exchange for their freedom the lúchorpáin grant him three wishes, one of which is to gain the ability to breathe underwater. This ability will work anywhere but Loch Rudraige (Dundrum Bay) in Ulster. He attempts to swim there anyway, and encounters a sea-monster called Muirdris, and his face is permanently contorted in terror. This disfigurement would disqualify him from the kingship, but the Ulstermen do not want to depose him, so they ban mirrors from his presence so he will never learn of his deformity. Seven years later he whips a serving girl, who in anger reveals the truth to him. Fergus returns to Loch Rudraige in search of the sea-monster, and after a two-day battle that turns the sea red with blood, kills it, before dying of exhaustion.

His kingship of Ulster, his association with the sword Caladbolg and his death in water have led some to identify him as a double of the Ulster Cycle character Fergus mac Róich, although the two characters appear together in the Caithréim Conghail Cláiringhnigh as enemies."

-taken from wikipedia

https://paganimagevault.blogspot.com/2022/03/fergus-goes-down-into-lake-by-stephen.html

#fergus mac leti#celtic mythology#celtic#celts#ireland#ulster#europe#st patricks day#leprachaun#pagan#history#paganism#european art#20th century art#art

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Muirdris and Fergus mac Léti by unknown artist

"The next day Fergus put on the shoes of Iubdan and went forth to Loch Rury, and with him went the lords of Ulster. And when he reached the margin of the lake he drew his sword and went down into it, and soon the waters covered him.

After a while those that watched upon the bank saw a bubbling and a mighty commotion in the waters, now here, now there, and waves of bloody froth broke at their feet. At last, as they strained their eyes upon the tossing water, they saw Fergus rise to his middle from it, pale and bloody. In his right hand he waved aloft his sword, his left was twisted in the coarse hair of the monster's head, and they saw that his countenance was fair and kingly as of old. "Ulstermen, I have conquered," he cried; and as he did so he sank down again, dead with his dead foe, into their red grave in Loch Rury.

And the Ulster lords went back to Emania, sorrowful yet proud, for they knew that a seed of honour had been sown that day in their land from which should spring a breed of high-hearted fighting men for many a generation to come.

Of this was sung:

King Fergus, son of Léte

Went on the sandbank of Rudraige;

A horror which appeared to him — fierce was the conflict —

Was the cause of his disfigurement."

-The Saga of Fergus mac Léti by D.A. Binchy

&

The High Deeds of Finn and Other Bardic Romances of Ancient Ireland by T.W. Rolleston

https://paganimagevault.blogspot.com/2022/03/the-muirdris-and-fergus-mac-leti-by.html

#fergus mac leti#pagan#paganism#literature#ireland#ulster#celtic#celts#celtic mythology#history#Muirdris

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

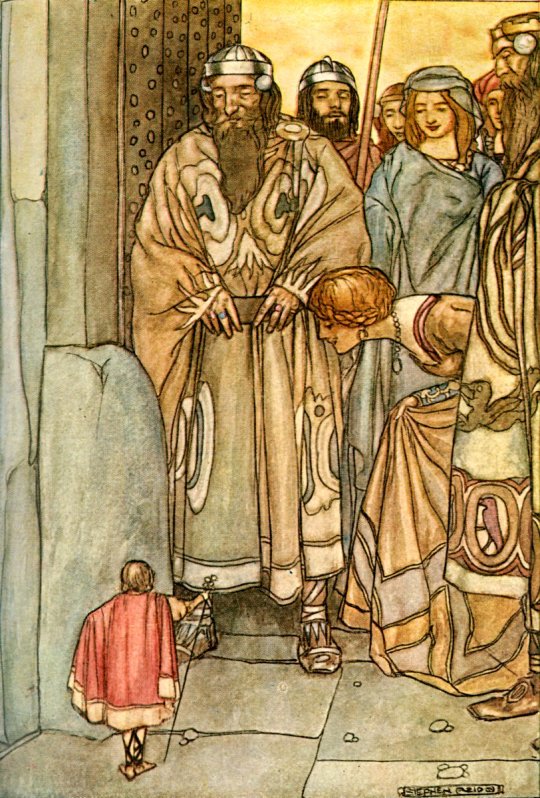

They all trooped out, lords and ladies, to view the wee man - by Stephen Reid 1910. The wee-man, Eisirt, in the presence of Fergus mac Léti.

"It happened on a day when Fergus son of Leda was King of Ulster, that Iubdan, King of the Leprecauns or Wee Folk, of the land of Faylinn, held a great banquet and assembly of the lords and princes of the Wee Folk. And all their captains and men of war came thither, to show their feats before the King, among whom was the strong man, namely Glowar, whose might was such that with his battle-axe he could hew down a thistle at one stroke. Thither also came the King's heir-apparent, Tiny, son of Tot, and the Queen Bebo with her maidens; and there were also the King's harpers and singing-men, and the chief poet of the court, who was called Eisirt.

All these sat down to the feast in due order and precedence, with Bebo on the King's right hand and the poet on his left, and Glowar kept the door. Soon the wine began to flow from the vats of dark-red yew-wood, and the carvers carved busily at great haunches of roast hares and ribs of field-mice; and they all ate and drank, and loudly the hall rang with gay talk and laughter, and the drinking of toasts, and clashing of silver goblets.

At last when they had put away desire of eating and drinking, Iubdan rose up, having in his hand the royal goblet of gold inlaid with precious many-coloured jewels, and the heir-apparent rose at the other end of the table, and they drank prosperity and victory to Faylinn. Then Iubdan's heart swelled with pride, and he asked of the company, "Come now, have any of you ever seen a king more glorious and powerful than I am?" "Never, in truth," cried they all. "Have ye ever seen a stronger man than my giant, Glowar?" "Never, O King," said they. "Or battle-steeds and men-at-arms better than mine?" "By our words," they cried, "we never have." "Truly," went on Iubdan, "I deem that he who would assail our kingdom of Faylinn, and carry away captives and hostages from us, would have his work cut out for him, so fierce and mighty are our warriors; yea, any one of them hath the stuff of kingship in him."

On hearing this, Eisirt, in whom the heady wine and ale had done their work, burst out laughing; and the King turned to him, saying, "Eisirt, what hath moved thee to this laughter?" "I know a province in Erinn," replied Eisirt, "one man of whom would harry Faylinn in the teeth of all four battalions of the Wee Folk." "Seize him," cried the King to his attendants; "Eisirt shall pay dearly in chains and in prison for that scornful speech against our glory."

Then Eisirt was put in bonds, and he repented him of his brag; but ere they dragged him away he said, "Grant me, O mighty King, but three days' respite, that I may travel to Erinn to the court of Fergus mac Leda, and if I bring not back some clear token that I have uttered nought but the truth, then do with me as thou wilt."

So Iubdan bade them release him, and he fared away to Erinn oversea.

After this, one day, as Fergus and his lords sat at the feast, the gatekeeper of the palace of Fergus in Emania heard outside a sound of ringing; he opened the gate, and there stood a wee man holding in his hand a rod of white bronze hung with little silver bells, by which poets are wont to procure silence for their recitations. Most noble and comely was the little man to look on, though the short grass of the lawn reached as high as to his knee. His hair was twisted in four-ply strands after the manner of poets and he wore a gold-embroidered tunic of silk and an ample scarlet cloak with a fringe of gold. On his feet he wore shoes of white bronze ornamented with gold, and a silken hood was on his head. The gatekeeper wondered at the sight of the wee man, and went to report the matter to King Fergus. "Is he less," asked Fergus, "than my dwarf and poet Æda?" "Verily," said the gatekeeper, "he could stand upon the palm of Æda's hand and have room to spare." Then with much laughter and wonder they all trooped out, lords and ladies, to the great gate to view the wee man and to speak with him. But Eisirt, when he saw them, waved them back in alarm, crying, "Avaunt, huge men; bring not your heavy breath so near me; but let yon man that is least among you approach me and bear me in". So the dwarf Æda put Eisirt on his palm and bore him into the banqueting hall.

Then they set him on the table, and Eisirt declared his name and calling. The King ordered that meat and drink should be given him, but Eisirt said, "I will neither eat of your meat nor drink of ale." "By our word," said Fergus, "'tis a haughty wight; he ought to be dropped into a goblet that he might at least drink all round him." The cupbearer seized Eisirt and put him into a tankard of ale, and he swam on the surface of it. "Ye wise men of Ulster," he cried, "there is much knowledge and wisdom ye might get from me, yet ye will let me be drowned!" "What, then?" cried they. Then Eisirt, beginning with the King, set out to tell every hidden sin that each man or woman had done, and ere he had gone far they with much laughter and chiding fetched him out of the ale-pot and dried him with fair satin napkins. "Now ye have confessed that I know somewhat to the purpose," said Eisirt, "and I will even eat of your food, but do ye give heed to my words, and do ill no more."

Fergus then said, "If thou art a poet, Eisirt, give us now a taste of thy delightful art." "That will I," said Eisirt, "and the poem that I shall recite to you shall be an ode in praise of my king, Iubdan the Great." Then he recited this lay:—

"A monarch of might

Is Iubdan my king.

His brow is snow-white,

His hair black as night;

As a red copper bowl

When smitten will sing,

So ringeth the voice

Of Iubdan the king.

His eyen, they roll

Majestic and bland

On the lords of his land

Arrayed for the fight,

A spectacle grand!

Like a torrent they rush

With a waving of swords

And the bridles all ringing

And cheeks all aflush,

And the battle-steeds springing,

A beautiful, terrible, death-dealing band.

Like pines, straight and tall,

Where Iubdan is king,

Are the men one and all.

The maidens are fair—

Bright gold is their hair.

From silver we quaff

The dark, heady ale

That never shall fail;

We love and we laugh.

Gold frontlets we wear;

And aye through the air

Sweet music doth ring—

O Fergus, men say

That in all Inisfail

There is not a maiden so proud or so wise

But would give her two eyes

Thy kisses to win—

But I tell thee, that there

Thou canst never compare

With the haughty, magnificent King of Faylinn!"

-The High Deeds of Finn and Other Bardic Romances of Ancient Ireland by T.W. Rolleston

https://paganimagevault.blogspot.com/2022/03/they-all-trooped-out-lords-and-ladies.html

#fergus mac leti#leprachaun#st patricks day#ireland#ulster#irish#pagan#paganism#european art#literature#book art#book illustration#art#celtic#celts

16 notes

·

View notes