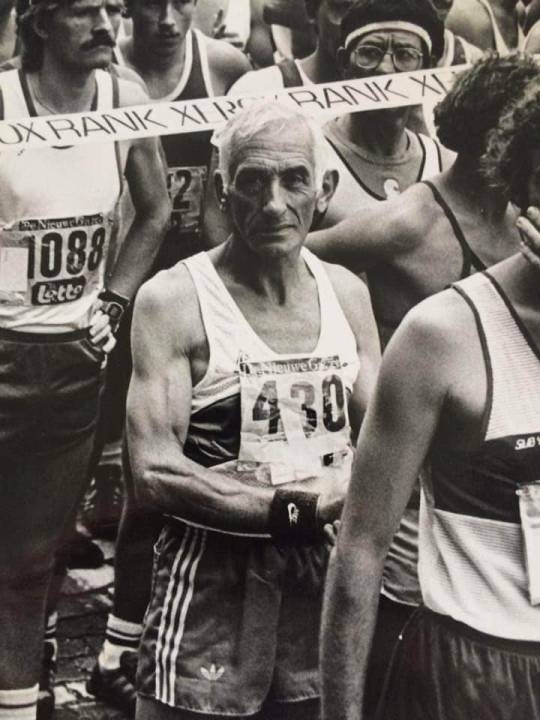

#from an article of him being the oldest runner at the finish of this marathon. He also swam the Strait of Dover as the oldest person ever (

Text

#My great-grandfather at 70#in 1989#from an article of him being the oldest runner at the finish of this marathon. He also swam the Strait of Dover as the oldest person ever (#emian1612#oldschool

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our Favorite Running Moments in Literature

New Post has been published on http://www.greggsdiabetes.com/our-favorite-running-moments-in-literature/

Our Favorite Running Moments in Literature

Surely, running and writing are parallel pursuits: for better or worse, both require you to spend an awful lot of time in your own head. With each, the pleasurable aspect (so far as it exists) is largely retrospective; it feels great to have written something decent, just as the best part of running is the feeling you get afterward—especially when there’s a pastry involved. With both activities, the actual process can be painful and frustrating and include prolonged periods of self-doubt. And that’s when things are going well.

It is only fitting, then, that our literary canon abounds with running references. Through the ages, the sport has featured prominently in various genres, from Greek myth to poetry to the modern short story. The following are some of the most notable running moments in literature.

“Metamorphoses,” Ovid, 8 A.D.

Nervous about an upcoming race? Read the myth of Atalanta and Hippomenes to see what real race-day pressure looks like. The huntress Atalanta is a great beauty with suitors aplenty, any of whom can win her by besting her in a foot race. Unfortunately for these aspiring lovers, Atalanta is “no less swift than a Scythian arrow.” More bad news: losing the race also means losing your life. Several young men can’t help themselves, however, and with predictable results. Along comes Hippomenes, who can’t help himself either, but he’s wise enough to ask the goddess Venus for help: “I pray you preside at my venture, aiding the fires that you yourself have ignited.” In what must be one of the first instances of technical doping, Venus gifts the young man with three golden apples, which he cunningly uses to distract Atalanta during the race. Alas, Hippomenes doesn’t sufficiently thank Venus for her assistance, an omission that eventually leads to him and Atalanta being turned into lions.

“To an Athlete Dying Young,” A.E. Housman, 1896

The scholar, classicist, and poet Alfred Edward Housman published only two volumes of poetry in his life, A Shropshire Lad (1896) and Last Poems (1922). According to the Norton Anthology of English Literature, Housman’s favorite theme is “the doomed youth acting out the tragedy of his brief life”—a subject that was all too relevant during World War I, when Housman’s poems were extremely popular in England. “To an Athlete Dying Young,” arguably Housman’s most recognizable poem today, certainly taps into this theme. The brief elegy invokes the romantic notion that a premature demise means not having to witness the fading of one’s glory, not having to “swell the rout” of “runners whom renown outran. And the name died before the man.” Beyond such quotable couplets, the morbidly clever transition that links its first two stanzas is reason enough for the poem to endure:

The time you won your town the race

We chaired you through the market-place;

Man and boy stood cheering by,

And home we brought you shoulder-high.

Today, the road all runners come,

Shoulder-high we bring you home,

And set you at your threshold down,

Townsman of a stiller town.

“The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner,” Alan Sillitoe, 1959

We owe running’s famous epithet to Alan Sillitoe’s 1959 short story about youthful rebellion in postwar England. “The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner” is the story of Smith, a young delinquent and ace cross-country runner. After robbing a bakery, Smith is sent to prison school, where he gets favorable treatment from the authorities thanks to his athletic talent. The school’s “pop-eyed potbellied governor” expects Smith to win a local meet and thereby serve as a prime exemplar for his institution, but Smith has other ideas. For the story’s beleaguered protagonist, the sensation of his morning runs is the source of “the only honesty and realness there was in the world.” It’s a wonder that running shoe marketers haven’t tried to make hay with this. Or maybe it isn’t.

“Pheidippides,” Robert Browning, 1878

We would be remiss to have a running-in-literature list without mentioning the poem that served as inspiration for the modern-day marathon. Many are familiar with the origin story of the race: As Persian attack ships landed on the coast near Marathon around 500 B.C., Pheidippides, a Greek messenger, ran more than 200 miles to Sparta and back, seeking military aid. The Spartans said no, but the Greeks won anyway. Dispatched to send news of the victory to Athens, Pheidippides covered the 25 miles on foot, delivered the good news, and then died of cumulative exhaustion. Though there is no historical evidence for the last part of the story, Englishman Robert Browning’s 19th-century poem “Pheidippides” helped ensconce this version in popular culture. At the urging of his friend Michel Bréal, a prominent French linguist who was enthralled by Browning’s poem, Pierre de Coubertain, the French aristocrat and Hellenophile credited as the founder of the modern Olympics, included a marathon event in the inaugural games of 1896.

“The Tortoise and The Hare,” Aesop, Circa 600 B.C.

No story about running is more prevalent in popular culture today than Aesop’s beloved fable. The tale of the persistent tortoise and the cocky hare is also probably the most useful allegory we have on the importance of pacing. There are endless animated versions. There’s a sculpture near the finish of one of the nation’s oldest cross-country courses. Of course there’s a running shoe store. But that’s not to say that the moral of the story has remained consistent. In a 2015 Super Bowl ad, the tortoise literally drives over his rival in a Mercedes AMG GT with a—presumably—sexy rabbit babe riding shotgun. (Tortoise: “Slow and steady, my ass.”) I don’t know about you, but I still prefer the original.

Original Article

0 notes