#galfridus monumotensis

Text

4. Brutus sends a letter to Pandrasus.

So as their chosen leader Brutus summoned the Trojans and fortified Assaracus’s towns. He took over the woods and hills, along with Assaracus and the multitude of men and women who continued to join them.

Then Brutus directed a letter to the king, in these words:

“To Pandrasus king of the Greeks, from Brutus leader of the survivors of Troy, greetings. It was a shame that a people arisen from the famed kin of Dardanus should be treated otherwise in your kingdom than your nobles’ peace of mind required; we have withdrawn, therefore, to the secret places of the woods.* For we would rather live like wild beasts, sustaining ourselves on game and forest plants in freedom, than be cheered any longer by common comforts while beneath the yoke of your servitude. If this offends your royal honour, we should not be blamed but pardoned, since it is the fault of every captive to wish to return to his former state. May you be moved with pity toward this people, therefore, to return the freedom which you stole from them, and permit them to dwell freely in the forest glades they have now occupied in order to flee their servitude. If not, then at least allow them safe passage to join the peoples of other lands.”

This passage was interesting because the letter was written in quite a different style from everything up to now. I wonder if it was drawn from or patterned on some other work? Anyway sarcasm is hard enough in English so the asterisked sentence especially had me tearing out my hair, I just finally cracked it today. (My husband couldn't get it and neither could my brother-in-law so I don't think it was just me being dumb?)

I used the first person plural to describe the Trojans in the letter for clarity. Geoffrey/Brutus has it in the third person singular with gens as the subject.

#arthuriana#history of the kings of britain#historia regum britanniae#geoffrey of monmouth#galfridus monumotensis#my translation#medieval literature#medieval latin#accusative with the infinitive my beloved#she is beautiful and I love her#she is also a pain in the butt at times

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

History of the Kings of Britain, continued...

2. Of the first inhabitants of Britain.

Britain is the most excellent of islands, situated in the Western Sea between France and Ireland. It is eight hundred miles in length, two hundred in width. Whatever suits the use of mortals, it provides in boundless plenty; for it is rich in every kind of metal, and boasts wide open fields and fine hills for farming, in which a variety of fruits arise richly from the soil in their seasons. It has woodlands filled with every kind of wild beast, and in the glades and other feeding-places of the woods these find grasses, while flowers of many colours disburse their honey to the hovering bees. It contains flourishing meadows, too, in lovely spots beneath the airy mountains, where clearest springs feed into bright streams with a gentle sound, inciting sweet sleep in those who lie upon their banks. It is further watered by lakes and rivers full of fish. Along the strait of the southern region (whereby one may sail to France), three noble rivers reach like three arms: these are of course the Severn, the Thames and (not least!) the Humber. Up them goods are brought across the sea from every nation, by passage of said strait.

The island was once adorned with eight and twenty cities. Of these, some are now crumbling into ruins and deserted; others, intact, still contain shrines to the saints, their towers upright in lasting beauty. Devout congregations of men and women there offer praise to God, according to the Christian tradition.

Finally, this island is inhabited by five peoples: the Normans* of course, as well as the Britons, the Saxons, the Picts, and the Scots. The earliest among these were the Britons, who once occupied the island from sea to sea until, thanks to their hubris, divine wrath descended on them and they fell to the Picts and the Saxons. That will suffice as a summary of how these things came about; it will be explained more fully in the following chapters.

*Lewis Thorpe says "Norman-French" here, which makes sense historically. My source says Romani, but I'm suspicious it may be a typo from Normanni.

#my translation#latin#medieval literature#galfridus monumotensis#geoffrey of monmouth#historia regum britanniae#history of the kings of britain#arthuriana#amateur latinist

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

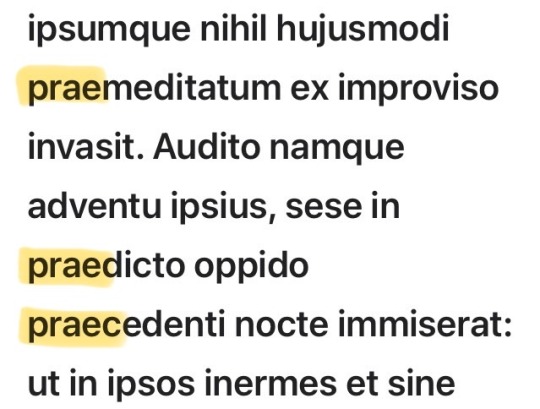

Geoffrey

what are you doing Geoffrey

#when the chronicler gets prefix-happy#geoffrey of monmouth#galfridus monumotensis#history of the kings of britain#historia regum britanniae#latin#medieval literature

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

3. Brutus, an exile after the death of his parents, seeks Greece

After the Trojan War Aeneas, fleeing the fall of the city with Ascanius, came by sea to Italy. There he was received with much honour by King Latinus; but Turnus, king of the Rutuli, envied him and went to war against him. Aeneas prevailed in the fight and, with Turnus dead, inherited both the kingdom of Italy and Lavinia, the daughter of Latinus.

At length Aeneas’s last day arrived, and Ascanius, now highest in royal power, established Alba beyond the Tiber and begat a son, whose name was Silvius. This Silvius, indulging a secret desire, took to wife a certain niece of Lavinia and made her pregnant. When his father Ascanius learned of this he ordered his wise men to discover with which sex the girl had conceived. Having discovered the certainty of the matter, the wise men told him that she was pregnant with a boy who would kill his father and mother, and after wandering many lands in exile, should come at last to the highest peak of honour.

Nor did this prophecy fail them. For when the day of her delivery arrived, the woman bore a boy-child, but died in the birth. He was given over to his nurse and was called Brutus. When thrice five years had gone by, the youth Brutus went hunting with his father and killed him with an unwitting bowshot. For as the servants were leading the deer onto their path, Brutus attempted to aim his arrow at the deer but instead struck his father below the chest. His relatives were incensed that he had done such a deed, and so he was exiled from Italy by the death of his father. Thus wandering, he came to Greece, and discovered the descendants of Helenus, Priam’s son, who were being kept in servitude beneath the rule of Pandrasus, king of the Greeks. Indeed Pyrrhus, the son of Achilles, had taken this Helenus and many others with him in chains, and kept them subdued in order to avenge his father’s death.

Having learned the lineage of these former fellow-citizens, Brutus lingered among them. He came to thrive greatly in military arts and in strength of character, so much so that he was beloved by kings and commanders before all the youth of the country. For he was wise among the wise, warlike among the warlike; and whatever he acquired in gold or silver ornaments, he bestowed the same on his fellow-soldiers. So his reputation became known throughout all nations, and the Trojans began to come to him, begging that he might lead them from their servitude to the Greeks. This they believed might be easily done, since they were now so multiplied in the land that they were reckoned at seven thousand (not counting women and children). Furthermore, there was a certain young man of high nobility in Greece, by name Assaracus, who also favoured their cause. He was born of a Trojan mother, so he had great confidence in them and that, with their help, he might be able to solve the troubles he was having with the Greeks. For Assaracus's brother was suing him over three fortresses which their father, upon dying, had given to him, and to which the brother was now trying to lay claim, since Assaracus had (supposedly) been born of a concubine. This brother was Greek by father and mother, and had allied with Greeks and their king for support in his suit.

And Brutus, looking over the number of Trojan men, as well as the fortresses of Assaracus which were at his disposal, agreed readily to their request.

#geoffrey of monmouth#galfridus monumotensis#history of the kings of britain#historia regum britanniae#latin#my translation#medieval literature#arthuriana#this one was such a pain but it got me back in translation mode

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Enter Geoffrey of Monmouth, or Galfridus Monumotensis if you're a stubborn human who doesn't think she needs a translation.

#might post some of mine if I'm reasonably sure of its accuracy#and/or feel like showing off#geoffrey of monmouth#galfridus monumotensis#historia regum britanniae#latin#medieval literature

6 notes

·

View notes