#he’s obsessed with his tiny neurotic husband

Text

geno… pls…

#he’s obsessed with his tiny neurotic husband#also still love that tanger was the one who picked THE h*rniest victory song on earth#sidney crosby#evgeni malkin#sidgeno#kris letang#po joseph#pittsburgh penguins

760 notes

·

View notes

Text

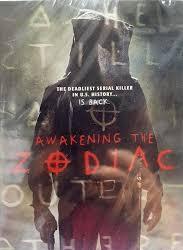

Awakening The Zodiac (2017)

Between the murders which took place in the summer of 1968 and the 2007 release of David Fincher’s masterpiece ZODIAC, there were a handful of feature films inspired by the mystique of the still unidentified serial killer known as the Zodiac. This list includes the 1971 releases DIRTY HARRY and THE ZODIAC KILLER, both released to a public still on edge from the relatively recent murders and ongoing missives from the killer, as well as 2007’s CURSE OF THE ZODIAC, a straight-to-video mess that may well have gotten greenlit and rushed into production to confuse audiences looking for Fincher’s film.

After 2007, there is only one: AWAKENING THE ZODIAC, released in 2017 to an audience that wasn’t really ready to get hyped up about the Zodiac Killer – at least, not until a year later, when law enforcement’s success in using genealogy databases to catch the Golden State Killer reinvigorated the public’s hope that Zodiac, too, could be identified by ancestral DNA connections.

There are any number of reasons for the relative rarity of features about the Zodiac, even in our true crime obsessed moment, I’m sure – fears of exploiting the suffering of real life victims, the complete lack of information about who the killer was despite the copious theorizing – but a big one surely has to be that ZODIAC just casts too large of a shadow. It’s just too definitive, packs too much information into its nearly two hour run time, cycles through too many theories and creates such a distinctive atmosphere of paranoia and obsession that it would be a real challenge for any subsequent film about the Zodiac Killer to distinguish itself

AWAKENING THE ZODIAC takes on that challenge, asking: well, what if we simply try to duplicate that paranoiac pall, but we also add in some spooky film reels like SINISTER and some scary traps like SAW? But not too many, just like one scene of each?

The film early on addresses the potential for exploitation by positing that the Zodiac is responsible for all sorts of unsolved murders not only in California, but across the U.S., and focusing its attentions on these crimes. (This does, of course, raise the question of whether this movie really needed to be directly about, rather than “inspired by”, the Zodiac murders.) However, this isn’t really clear until later in the film, so during the opening scene which depicts the 1968 murder of a couple in their car, you may well think its depicting one of Zodiac’s canonical murders unless you happen to know that none of his documented victims were named Adam and Lula and none took place in Hunter’s Point.

Adam and Lula are dispatched with only the minor hitch of Lula stabbing Zodiac in the ankle with a knife – a detail that has no relevance as it does not affect the Zodiac’s gait later in the film – and after a brief credit sequence of a bespectacled man poring over reels of film, we flahs forward to what is presumably the present day. (There is no title to establish it, but the rest of the film takes place in Virginia in a year that has computers and cell phones.)

Here we meet Mick (Shane West of the Germs) and his wife Zoe (Leslie Bibb), a married couple doing their best to scrape by in their tiny trailer. Zoe’s had to go freelance since the salon she worked for closed, but she’s landing maybe a client a day. Mick owns a landscaping business, but it’s not particularly lucrative in a town that seems to be struggling overall. Mick doesn’t have any concrete plans to haul them out of their financial hole. Instead he dreams of striking it rich selling the contents of abandoned storage lockers with his partner Phil (Matt Craven), the eccentric vet who owns the local pawn shop.

Although he got his start with horror feature NOSTROM, writer/director Jonathan Wright has mostly spent the past decade at the helm of Hallmark romances with titles like LOVE, ROMANCE, & CHOCOLATE and CHRISTMAS JARS. It shows – in a good way! The one factor distinguishing AWAKENING THE ZODIAC from most exploitation thriller schlock is the surprising charm, humor, and affection shared by Zoe and Mick, despite their frequent and completely reasonable conflicts.

Zoe often feels the need to be the funkiller / adult in the room in response to her husband’s recklessness, but it’s a role that even she recognizes is thankless, so more often than not she gives in to the fun. Mick characterizes himself as congentially unable to take shit from anyone, but this doesn’t extend to his wife’s completely reasonable anger at him doing shit like spending their grocery money on what is basically a blind bet in hopes of striking it rich.

The action begins when Mick spends that grocery money to go halfsies on a $1200 locker, rumored to be owned by a rich old woman. They don’t find any antiques worth more than a few hundred bucks, but they do find a box of dated film reels shoved into an old dresser. One of these reels depicts the murder of Adam and Lulu, with the camera well positioned to catch the Zodiac’s full hood and black clothing with its characteristic symbol. The film once again avoids direct exploitation when the reel which was presumably going to depict the 9-27-68 murder of Cecilia Shephard (and attempted murder of Bryan Hartnell) burns before it can depict the action. Mick and Zoe are freaked and befuddled, but Harvey quickly explains who the Zodiac Killer is to these two dumb kids and we’re on our way.

Which way? Well, fortuitously, the San Francisco Police have recently reopened the case and are offering a $100,000 reward for information that leads to the identity of the killer. Aren’t film reels depicting the Zodiac committing murders and the lead about the storage locker sufficient information already, given that the police could follow those leads to figure out who rented the locker?

Mick watches a lot of Unsolved Mysteries, and he says no – they need to bring a definitive identification to the police in order to claim the reward. Instead, our amateur investigators decide to follow the leads themselves to discover the identity of the storage locker owner, which mostly involves a lot of breaking and entering.

It should go without saying, but: these are not actions you take if you are planning to turn over information to the police in order to claim a financial reward and not go to prison for breaking and entering. These are actions you take if you are planning to turn all this illegally obtained information into clout for your pseudonym on your murder mystery message board – and not even one of the respectable ones.

While they’re on the trail of a man who is presumably in his seventies and may very well have let his rent payments lapse because he’s dead, the film feels the need to establish stakes – and get in a rare gore scene – by having a mysterious figure kidnap and murder the manager of the U-Store-All. Mick also begins to receive some heavy breathing phone calls and hears noises outside of his trailer, becoming increasingly paranoid as the film goes on and he grows more obsessed with the case by reading message boards and listening to audio recording of the Zodiac over and over.

The film desperately wants to capture the neurotic mood of ZODIAC as the trio tracks leads, does research, solves ciphers, argues over suspects, and devolve into obsession, but it just can’t. It populates its tiny cast with red herrings – including Mick and Zoe’s neighbor Ray who portentously warns Mick, “Don’t mess around with shit you don’t understand,” claiming to have heard through the thin walls of the trailer that he’s investigating the “absolute genius” Zodiac – but even with the established fact that the Zodiac is still alive and murdering, the stakes feel low. He’s old, guys. He’s old and you can go to the police at literally any time.

THIRD ACT SPOILERS!

Our intrepid ding-dongs eventually alight on a potential suspect – Ben Ferguson (Kenneth Welsh), the son of the woman whose name was used to rent the storage locker. He was in the military! He used to live in San Francisco! He has reels of 8mm film in his house! He wrote an article about the Zodiac, positing that he was involved in a series of murders across the U.S.! He’s totally not the killer, though, and as Mick and Zoe get no closer to the Zodiac, he gets closer to them. After murdering Harvey and Ben, the Zodiac manages to kidnap Zoe and leave a coded message for Mick, demanding that he meet him at an abandoned slaughterhouse to trade the film reels for his wife.

And who is the Zodiac? Surprise, guys – it’s Stephen McHattie, the recognizable actor who gets an “and” title in the opening credits and who previously popped up for one line as Ben Ferguson’s neighbor. Once that was established it could never be anyone but Stephen McHattie.

At this point the film devolves into farce as Zodiac sings a creepy rendition of Yankee Doodle Dandy (it’s no Hurdy Gurdy Man) and confines Zoe to an electrified cage maze, telling her “I left you a way out, if you’re brave enough to try.” He monologues for a while about his “legend”, why he’s in Virginia (he stalked Ben Ferguson across the U.S., intending to kill him, but ended up liking the town), and why he missed his payments on the storage locker (his memory isn’t what it used to be). Eventually Mick arrives for the showdown and he and Zoe, who managed to find that way out, take Zodiac out for good.

However, THE LEGEND CONTINUES because even with a body, the authorities still can’t figure out the Zodiac’s original identity. At least Mick has learned a lesson, though – he tells Zoe that his former boss offered him his old job at the factory and he’s accepted: “It’s time to make a real go of things, baby.” No more storage lockers and serial killers for this couple.

Mick also decides to take some responsibility by going outside to fix a flickering light outside their trailer, which leads to maybe the most baffling ending I’ve ever seen in a film. Zoe gets freaked out after hearing a noise outside, not immediately assuming (as most would) that it’s her husband fixing that light. As we cut to outside, Mick is nowhere to be found. There is, however, a man who steps forward with a black boot – cut to credits.

That’s right – this film ends by implying that there is a SECOND Zodiac Killer who is at large and for some reason in this trailer park!

God love it, this film is a mess. A well-intentioned mess, a not completely incompetent mess (it’s dingy as hell, attempting to capture the desaturated atmosphere of ZODIAC, but it’s well-filmed), a surprisingly charming mess, but a mess regardless. It’s also the kind of mess that I almost wish was even dumber that it is – like, how great would it be if it turned out Zoe was the Zodiac Killer’s secret daughter? Once you’re in this far, you might as well go whole hog.

I watched this on: Hulu

0 notes

Text

A Stay-at-Home Self-Analysis

I woke up a few days ago and forgave myself. For everything. It was ok to be me and every decision I had made, good or bad, was part of my upbringing, environment and genetic make-up. It’s ok that I am anxious and battle addictions. The stay at home order has enabled me to think, to analyze and to let go.

I loved my parents, but boy, were they characters. My handsome Italian father, was obsessed with his weight and being a golf pro at a club on the south side of Chicago. That was his persona, his life, his true love. Playing golf, schmoozing and interacting with people who had a lot more money than he ever would have. The golf course was his kingdom and he had many loyal subjects.

My beautiful, intelligent Greek mother, who was not allowed to go to college in 1941 because my Greek grandfather said, “girls didn’t have to go to college,” became a brilliant, angry, super-neurotic woman for the rest of her life, because of that decision. Her anger, in my opinion, killed her, as her rages created high blood pressure, obesity and emotional dependence on her family.

I grew up in a small four room apartment in a four flat. I was an only child and lonely. I still am and deal with it often. My parents loved me and I loved them. They loved each other, “not wisely but too well,” and they fought like cats and dogs for 60 years, until her death.

One momentous argument involved a whole watermelon being hurled across a tiny kitchen back and forth while a small child cried (me). Albee’s George and Martha might have been modeled on them, without the alcohol. They had loud voices, articulate even in anger, that were positively Wagnerian.

My mother had a short fuse. During one argument, as my Dad prepared to walk away from her, Mom ripped the undershirt right off his back. She had very strong hands. I was crying. I yelled I was going to call the police and that shut them up. They were embarrassed that their anger had escalated and was being noticed. There was a Stanley Kowalski edge to this incident that I never forgot.

I have been in and out of therapy for many years, but not until I was older and had the time and health insurance to cover it. When I was a teen in the 60’s and 70’s, I didn’t know many people who went to therapists. In my circle, it wasn’t done often. Problems weren’t talked about, swept under the carpet or perhaps confided to the parish priest.

My daughter lives in Europe and has an online therapist in Texas. They talk weekly. I think it’s fabulous.

Today when she and I FaceTimed, we spoke about the past, and getting past the past. I asked her to forgive me for not being as patient with her as I could have been, when she was having teenage issues. I said having a job as a city school teacher and being a single parent was difficult. My demanding parents who stuck their nose in my business every day of their lives brought another element of anxiety. My ex-husband? Divorce brings stress. I was also attached to my broken down Victorian home near Wrigley Field that I didn’t want to give up but worried about money.

My daughter thanked me for the apology. She understood what I was trying to say, as she was processing her past at a much younger age. I am so proud of her for not waiting until she was 50 years old like I did. I am now 67.

I told my ex-husband a few years ago that I was sorry that I only knew how to deal with our issues with anger, as that was what I had learned from my Mom and Dad. He looked stunned. I never knew how to step back and walk away from a situation until I was older. I am still learning.

The COVID-19 disaster is creating a lot of private space for us. We can think and self-analyze with or without the help of a therapist. I have been to AA meetings where the 12 steps are a tool for recovering addicts to find health and peace. There is one step that I think should be added. We need to forgive everyone who has wronged us. It works both ways, forgiving and being forgiven. It’s crucial to growth and emotional healing.

When I woke up a while ago and realized that I was a wonderful, beautiful human being with many talents and friends, in spite of, because of, the strange angry, loving parents I grew up with- it was a revelation. It was my personal eureka moment of enlightenment and fireworks exploded in my brain. I was so happy. Even though I am a work in progress and have many goals to achieve, I can look back without regret and look forward with anticipation.

A Stay-at-Home Self-Analysis syndicated from

0 notes

Text

A Stay-at-Home Self-Analysis

I woke up a few days ago and forgave myself. For everything. It was ok to be me and every decision I had made, good or bad, was part of my upbringing, environment and genetic make-up. It’s ok that I am anxious and battle addictions. The stay at home order has enabled me to think, to analyze and to let go.

I loved my parents, but boy, were they characters. My handsome Italian father, was obsessed with his weight and being a golf pro at a club on the south side of Chicago. That was his persona, his life, his true love. Playing golf, schmoozing and interacting with people who had a lot more money than he ever would have. The golf course was his kingdom and he had many loyal subjects.

My beautiful, intelligent Greek mother, who was not allowed to go to college in 1941 because my Greek grandfather said, “girls didn’t have to go to college,” became a brilliant, angry, super-neurotic woman for the rest of her life, because of that decision. Her anger, in my opinion, killed her, as her rages created high blood pressure, obesity and emotional dependence on her family.

I grew up in a small four room apartment in a four flat. I was an only child and lonely. I still am and deal with it often. My parents loved me and I loved them. They loved each other, “not wisely but too well,” and they fought like cats and dogs for 60 years, until her death.

One momentous argument involved a whole watermelon being hurled across a tiny kitchen back and forth while a small child cried (me). Albee’s George and Martha might have been modeled on them, without the alcohol. They had loud voices, articulate even in anger, that were positively Wagnerian.

My mother had a short fuse. During one argument, as my Dad prepared to walk away from her, Mom ripped the undershirt right off his back. She had very strong hands. I was crying. I yelled I was going to call the police and that shut them up. They were embarrassed that their anger had escalated and was being noticed. There was a Stanley Kowalski edge to this incident that I never forgot.

I have been in and out of therapy for many years, but not until I was older and had the time and health insurance to cover it. When I was a teen in the 60’s and 70’s, I didn’t know many people who went to therapists. In my circle, it wasn’t done often. Problems weren’t talked about, swept under the carpet or perhaps confided to the parish priest.

My daughter lives in Europe and has an online therapist in Texas. They talk weekly. I think it’s fabulous.

Today when she and I FaceTimed, we spoke about the past, and getting past the past. I asked her to forgive me for not being as patient with her as I could have been, when she was having teenage issues. I said having a job as a city school teacher and being a single parent was difficult. My demanding parents who stuck their nose in my business every day of their lives brought another element of anxiety. My ex-husband? Divorce brings stress. I was also attached to my broken down Victorian home near Wrigley Field that I didn’t want to give up but worried about money.

My daughter thanked me for the apology. She understood what I was trying to say, as she was processing her past at a much younger age. I am so proud of her for not waiting until she was 50 years old like I did. I am now 67.

I told my ex-husband a few years ago that I was sorry that I only knew how to deal with our issues with anger, as that was what I had learned from my Mom and Dad. He looked stunned. I never knew how to step back and walk away from a situation until I was older. I am still learning.

The COVID-19 disaster is creating a lot of private space for us. We can think and self-analyze with or without the help of a therapist. I have been to AA meetings where the 12 steps are a tool for recovering addicts to find health and peace. There is one step that I think should be added. We need to forgive everyone who has wronged us. It works both ways, forgiving and being forgiven. It’s crucial to growth and emotional healing.

When I woke up a while ago and realized that I was a wonderful, beautiful human being with many talents and friends, in spite of, because of, the strange angry, loving parents I grew up with- it was a revelation. It was my personal eureka moment of enlightenment and fireworks exploded in my brain. I was so happy. Even though I am a work in progress and have many goals to achieve, I can look back without regret and look forward with anticipation.

from https://ift.tt/2Ldi2gs

Check out https://peterlegyel.wordpress.com/

0 notes

Text

A Stay-at-Home Self-Analysis

I woke up a few days ago and forgave myself. For everything. It was ok to be me and every decision I had made, good or bad, was part of my upbringing, environment and genetic make-up. It’s ok that I am anxious and battle addictions. The stay at home order has enabled me to think, to analyze and to let go.

I loved my parents, but boy, were they characters. My handsome Italian father, was obsessed with his weight and being a golf pro at a club on the south side of Chicago. That was his persona, his life, his true love. Playing golf, schmoozing and interacting with people who had a lot more money than he ever would have. The golf course was his kingdom and he had many loyal subjects.

My beautiful, intelligent Greek mother, who was not allowed to go to college in 1941 because my Greek grandfather said, “girls didn’t have to go to college,” became a brilliant, angry, super-neurotic woman for the rest of her life, because of that decision. Her anger, in my opinion, killed her, as her rages created high blood pressure, obesity and emotional dependence on her family.

I grew up in a small four room apartment in a four flat. I was an only child and lonely. I still am and deal with it often. My parents loved me and I loved them. They loved each other, “not wisely but too well,” and they fought like cats and dogs for 60 years, until her death.

One momentous argument involved a whole watermelon being hurled across a tiny kitchen back and forth while a small child cried (me). Albee’s George and Martha might have been modeled on them, without the alcohol. They had loud voices, articulate even in anger, that were positively Wagnerian.

My mother had a short fuse. During one argument, as my Dad prepared to walk away from her, Mom ripped the undershirt right off his back. She had very strong hands. I was crying. I yelled I was going to call the police and that shut them up. They were embarrassed that their anger had escalated and was being noticed. There was a Stanley Kowalski edge to this incident that I never forgot.

I have been in and out of therapy for many years, but not until I was older and had the time and health insurance to cover it. When I was a teen in the 60’s and 70’s, I didn’t know many people who went to therapists. In my circle, it wasn’t done often. Problems weren’t talked about, swept under the carpet or perhaps confided to the parish priest.

My daughter lives in Europe and has an online therapist in Texas. They talk weekly. I think it’s fabulous.

Today when she and I FaceTimed, we spoke about the past, and getting past the past. I asked her to forgive me for not being as patient with her as I could have been, when she was having teenage issues. I said having a job as a city school teacher and being a single parent was difficult. My demanding parents who stuck their nose in my business every day of their lives brought another element of anxiety. My ex-husband? Divorce brings stress. I was also attached to my broken down Victorian home near Wrigley Field that I didn’t want to give up but worried about money.

My daughter thanked me for the apology. She understood what I was trying to say, as she was processing her past at a much younger age. I am so proud of her for not waiting until she was 50 years old like I did. I am now 67.

I told my ex-husband a few years ago that I was sorry that I only knew how to deal with our issues with anger, as that was what I had learned from my Mom and Dad. He looked stunned. I never knew how to step back and walk away from a situation until I was older. I am still learning.

The COVID-19 disaster is creating a lot of private space for us. We can think and self-analyze with or without the help of a therapist. I have been to AA meetings where the 12 steps are a tool for recovering addicts to find health and peace. There is one step that I think should be added. We need to forgive everyone who has wronged us. It works both ways, forgiving and being forgiven. It’s crucial to growth and emotional healing.

When I woke up a while ago and realized that I was a wonderful, beautiful human being with many talents and friends, in spite of, because of, the strange angry, loving parents I grew up with- it was a revelation. It was my personal eureka moment of enlightenment and fireworks exploded in my brain. I was so happy. Even though I am a work in progress and have many goals to achieve, I can look back without regret and look forward with anticipation.

from https://ift.tt/2Ldi2gs

Check out https://daniejadkins.wordpress.com/

0 notes

Text

Joy Williams, the Art of Fiction in the Paris Review

Joy Williams couldn’t find her glasses before a lecture some years ago and used prescription sunglasses instead. During Williams’s walk to the podium, an audience member was heard asking if the writer had gone blind; another remarked how inspiring it was for Williams to recall the lecture from memory. She had been asked to discuss craft. She did not discuss craft. She discussed Kraft cheese and the “twiddling” nature of art pursued “within a parameter of hours in prisons, nursing homes, and kindergartens,” and then she opened a valve. What would be the point, she said,

to discuss the craft of Jean Rhys, Janet Frame, Christina Stead, Malcolm Lowry, all of whose works can teach us little about technique, and whose way of touching us is simply by exploding on the lintel of our minds. It is not technique that guided them. Their craft consisted of desire.

She went on:

We are American writers, absorbing the American experience. We must absorb its heat, the recklessness and ruthlessness, the grotesqueries and cruelties. We must reflect the sprawl and smallness of America, its greedy optimism and dangerous sentimentality. And we must write with a pen—in Mark Twain’s phrase—warmed up in hell. We might have something then, worthy, necessary; a real literature instead of the Botox escapist lit told in the shiny prolix comedic style that has come to define us.

She smiled, thanked the audience, and sat. There were no questions. A student at the reception wondered aloud if tonight’s craft talk could have possibly destroyed future craft talks. “I hope so,” her friend said.

The Paris Review had already run several of the earliest, weirdest Joy Williams stories before George Plimpton agreed to publish State of Grace under the magazine’s book imprint in 1973. The novel, her first, would be nominated for the National Book Award when its author was thirty. (She lost to Gravity’s Rainbow.) She went on to write three more eerie, eccentric novels of life on the American margins as well as four renowned collections of stories, upon which her reputation solidly rests. Many have attained cult status beyond the normal anthologies—“Traveling to Pridesup,” “The Blue Men,” “Rot,” “Marabou,” “Brass”—and are frequently passed around M.F.A. departments with something like subversive glee. They are, as Williams probably hoped, unteachable as craft. The New York Times admitted more than it meant to, perhaps, when a reviewer claimed her work was “probably not for everyone.” Over the decades, wildly different stylists—Donald Barthelme, Don DeLillo, Raymond Carver, William Gass, Karen Russell, Bret Easton Ellis, James Salter, Ann Beattie, Tao Lin—have all expressed unqualified admiration.

Williams was married to Rust Hills, fiction editor of Esquire, for thirty-four years, until his death in 2008. Now she divides the seasons between Arizona, Florida, and New England, crisscrossing the country in an old Ford Bronco with two sable-black German shepherds, writing in motels or as the occasional guest of a college. She uses a flip phone. She types postcards in lieu of e-mail. She has never owned a computer. She continues to wear the same prescription sunglasses, indoors or out, night or day.

She was a writer-in-residence at the University of Wyoming when this interview was arranged. It was October; snow whipped between the ranges like a sandstorm, while several big rigs had jackknifed on black ice coming into Laramie. I phoned from a coffee shop, and she gave me directions: thirty miles north to a ranch where the Bureau of Land Management had relocated herds of wild mustangs. Williams was staying in a red-roofed log cabin with a porch swing and fire pit. The sun broke through like something from Doctor Zhivago. Everything about the wintry scene felt germane to this particular artist: the scope and grandeur of the natural world, the monkish quiet, two dogs with lively personalities, and—roaming everywhere—hundreds of wild horses, nervous and arrogant. Huddled in a hoodie, Williams made coffee with almond milk before sitting across from me at a pine table. She got up several times to retrieve objects or fuss with the dogs. When the talk was over, she drove us into town for a martini and we returned after dark. There was a fat moon. She cut the truck’s headlights and moved, very slowly, through the herds as they sniffed and stepped aside, hides glowing with moonlight.

“Forget the interview,” she said. “Write about this.”

Paul Winner

INTERVIEWER

What do you teach, when you’re visiting a college? Is there a philosophy you try to impart?

WILLIAMS

James Salter once taught a whole course of novels that were written when the authors were the same age as his students. Isn’t that clever? Well, it could also be intimidating. Mostly you just need to support them until they get older and sort themselves out a bit.

INTERVIEWER

What kind of child were you?

WILLIAMS

An only child, growing up in Maine. My father was a Congregational minister. He had a church in Portland. It was a big city church, a beautiful, very formal place. His father was a Welsh Baptist minister who, as a young man, won the eisteddfod in Wales. His prize was a large, ornately carved chair, the bard’s chair, which I wanted very badly as a child. The chair made it to this country but was given to my father’s older brother, who gave it to a historical society in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, from which it was washed away in a flood. Preachers and coal miners, my genealogy.

INTERVIEWER

You said you still own your father’s Bible.

WILLIAMS

Oh, yes. He had lots of Bibles. I kept them all. I’ve got my father’s notebooks, his sermons. One of these days I’ll get them organized. My mother always said she was going to throw them out. They’re not meant to be read, they’re meant to be heard, she said. But I’ve still got them.

INTERVIEWER

Were you a good student? An avid reader?

WILLIAMS

When I was a child I thought the answers to tests had to be transmitted to a person through some kind of food. Perhaps I read it in a book. In any case, it seems I was always preparing myself for tests, or thought I was. I was uneasy with my presence in life. Who was I, anyway? What was I supposed to do? Even with my obsession with preparing for the tests of the day, I was an indifferent student before I went to college. I had my heart set on Colby, in Maine, this tiny liberal-arts college, but I didn’t get in. Marietta, in Ohio, is where my father went, so I went there. I loved it. I was Phi Beta Kappa.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have your key?

WILLIAMS

I do. Do you want to see it? The first was stolen, so my husband tracked down the Phi Beta Kappa people and got me another one. They don’t give it to just anybody, apparently. As I said, I loved college. I had the guidance of an elderly, morose, chain-smoking English professor—Dr. Harold Dean. I never spoke well or argued well in class. But filling up blue books with the gleanings and gleamings of thought, which somehow became a new thought—that was very fulfilling to me. I read Donne, Dickinson, transcendentalism, Eliot, Camus, surrealism. I drank it all up. I was obsessed with Dickinson. The professor gave me her collected poems, three volumes in a box set. A lovely thing. It fared very badly in Florida, all those years, eaten by insects.

INTERVIEWER

Is it true that when you left home, your family gave you multiple copies of the same book?

WILLIAMS

Miss MacIntosh, My Darling. When I was going off to college, I got two copies of this thing, this impossibly neurotic, very strange book by this woman who’d been working on it her whole life, Marguerite Young. What were they thinking? I got Berryman’s collected poems at some point for a birthday, but back then I guess my parents read a review somewhere and thought, You know, well, Joy thinks she’s going to be a writer.

INTERVIEWER

Had you already started writing? You were published quite young.

WILLIAMS

Not so young.

INTERVIEWER

Twenty-two.

WILLIAMS

A lot of those stories aren’t collected. “The Roomer,” my first published story—it was in The Carolina Quarterly and won an O. Henry—that’s never been collected. I didn’t want to. I thought it was sinister and immature. George Plimpton introduced me once at a reading in that voice of his and said that he’d discovered me, that he’d done the first published story of mine. I had to speak up, from the audience, “Uh . . . ” He laughed, charmingly.

INTERVIEWER

From college, you went to Iowa?

WILLIAMS

On graduating, I wanted to join the Peace Corps. It was the early sixties, after all. But the cadaverous Dr. Dean—really, his looks were remarkable—he convinced me otherwise. He wanted me to become a writer. He wanted me to go to the writing program at the University of Iowa and become a writer. So another two years in the Midwest, far from my heart’s home in Maine. The workshop at Iowa met in Quonset huts on the river, then—freezing.

INTERVIEWER

You mentioned that Iowa was, for you, two years of social awkwardness. A shy, Eastern daughter of a minister surrounded by all these big alpha-male writers, Andre Dubus, Raymond Carver—

WILLIAMS

Ray Carver was in the poetry classes. He was always a poet. I knew his wife Maryann better. We were waitresses together, but I was always getting fired. In the workshops I studied with R.V. Cassill and Vance Bourjaily. A more imperfect match there cannot be imagined. Richard Yates came in at some point, I think. Eleven Kinds of Loneliness had just come out in paperback. He seemed a little remote and anxious to me, though not particularly lonely. Revolutionary Road was hugely impressive, but the stories touched me not at all. They seemed old-fashioned, resolving themselves on small matters.

INTERVIEWER

Had you begun your first novel, State of Grace?

WILLIAMS

I graduated, got married, and moved to Florida, where my husband worked at the Sarasota Herald-Tribune. We had a dog, a beach, a Jaguar XK150, black, which to this day I wish I still possessed. Then the husband was trans- ferred to Tallahassee. I didn’t want to live in the big city, I wanted to live in the country. We rented a trailer in the middle of tangled woods on the St. Marks River. Didn’t know a soul, husband away all day. I wrote State of Grace there. Excellent, practically morbid conditions for the writing of a first novel. We returned to Siesta Key, and I got a job working for the Navy at the Mote Marine Laboratory, researching shark attacks.

INTERVIEWER

Shark—

WILLIAMS

The only job I’ve ever had, other than teaching. Well, there was the waitressing. But I was writing, I was getting published in The Paris Review. Really, I had no idea what I was doing.

INTERVIEWER

Did you feel alone with the work? Utterly adrift?

WILLIAMS

I had no connections, no writing circle. I typed everything single-spaced so it would look as though it were already published. Looking at those manuscripts now, I’m amazed at how fluid everything was. No hesitation, no correction, no revising. What a gift! What or who had given me this gift? I mean, the stories weren’t brilliant. They might not have even been particularly good. But I wrote stories, I began and ended them. I didn’t have much experience with anything, but I had my thoughts. I believed stories should have a purity and not be about what was going on—and there was a lot going on, of course, in my life. My husband and I acquired a toucan, then we had a baby. No one knew I was going to have a baby. I was skinny, no one seemed to remark. You know, I didn’t even tell my parents, my dear, dear, supportive, loving parents. When my husband called them on April 6, the day Caitlin was born, they didn’t believe him. Why did I do that? I don’t know. It was so cruel. I suppose I was a little odd, a little secretive. I still have secrets.

INTERVIEWER

Is that what stories are to you? Secrets?

WILLIAMS

I recently received a letter from an Iowa Workshop grad—typical—seeking my participation in a “collaborative” interview. The question was, Why do short stories matter and why should we value them? What a retro question. It sounded like something out of the 1940s. I was too weary for a reply, but I think they probably don’t matter all that much. A herd of wild elephants matters more. And which stories are we talking about? There are so many of them.

INTERVIEWER

Can you define a story, if not its usefulness?

WILLIAMS

What a story is, is devious. It pretends transparency, forthrightness. It engages with ordinary people, ordinary matters, recognizable stuff. But this is all a masquerade. What good stories deal with is the horror and incomprehensi- bility of time, the dark encroachment of old catastrophes—which is Wallace Stevens, I think. As a form, the short story is hardly divine, though all excel- lent art has its mystery, its spiritual rhythm. I think one should be able to do a lot in less than twenty pages. I read a story recently about a woman who’d been on the lam and her husband dies and she ends up getting in her pickup and driving away at the end, and it was all about fracking, damage, dust to the communities, people selling out for fifty thousand dollars. It was so boring.

INTERVIEWER

You tend to mistrust the literal. How do you conceive stories? Do you start with metaphor?

WILLIAMS

I honestly don’t know how I approach such things. That’s the frustration. You want to have your writing do more, and speak more, and yet ... Do you want more coffee?

INTERVIEWER

So back to Florida, early 1970s, holed up in a rented trailer.

WILLIAMS

This may be boring or irrelevant, but I go away to Yaddo, in the winter. I write a story called “Taking Care.” I show the story to a writer there, a sophisticated feminist from New York. She suggests I cut the final line, “Together they enter the shining rooms.” I am dismayed. I become suspicious of readers. Of course I will not cut the line. It carries the story into the celestial, where it longs to go.

INTERVIEWER

In your mind, you’ve finally written your first good story.

WILLIAMS

I send the story to The New Yorker. I receive a nice letter in return. Rather, it begins nicely and admiringly but ends on a somewhat accusatory note. The story is insincere, inorganic, labored. Only once in my career will I appear in The New Yorker. And as Ann Beattie said, the only thing worse than never appearing in The New Yorker is being accepted only once by The New Yorker. I send it to a new magazine called Audience, a hardcover, oversize, heavily illustrated magazine. Its fiction editor is Rust Hills. He loves the story. He is utterly moved by the story. In a few months I return to Yaddo—winter again—and he, quite by coincidence, is there, too.

INTERVIEWER

When was this?

WILLIAMS

I met Rust in 1972. We were both married to other people and I had a two-year-old. By 1974, we were married to each other and Rust had formally adopted Caitlin and given her his name. He had a house in Stonington, Connecticut, and I had a cypress house on a lagoon close by the beach, on Siesta Key. The only writer around was John D. MacDonald. We got to know artists through two of our dear friends, the abstract expressionist Syd Solomon and his wife, Annie. We met Philip Guston, Marca-Relli, Chamberlain, Rivers.

INTERVIEWER

The early seventies were charged with feminist consciousness—Toni Morrison, Germaine Greer, The Female Eunuch. You didn’t feel a part of that? You mentioned once that you sensed female writers of that time were everywhere and were expected to be engaged and angry but ended up being terribly conformist.

WILLIAMS

God, yes. Back then you had to be a certain type of writer. You had to be one of these women writing the sort of thing that other people could, you know, find a book on.

INTERVIEWER

Speaking of feminism, I found an article from a Sarasota paper reporting on a literary festival sometime in the 1970s, attended by various luminaries. You were unknown. I believe you are described in the article as being the “tanned, leggy companion” of editor Rust Hills.

WILLIAMS

The word you seek is “sinewy.” Rust organized a writers conference at New College, in Sarasota. It was 1977, I believe. Astonishingly, he got William Gaddis and William Gass to come and actually confer with students. The conference was never repeated, and, though a modest success, I think the students were somewhat baffled. Gaddis and Gass—who were Gaddis and Gass? They sounded like a struggling law firm. Rust wasn’t at Esquire when we met, as I said. Gordon Lish was there and published several of my stories. I was not his big success. Ray Carver was his big success. Lish cut one of my stories, “The Lover,” in half and made it a very good story. He didn’t talk a lot about your stories, he didn’t explain what or why, he just cut and cut.

INTERVIEWER

Your second novel, The Changeling, came out the next year. A review in the Times used your book as a springboard to complain about the vague aims and language of the literary avant-garde. Did you think you were avant-garde?

WILLIAMS

Well, The Changeling, as you might know, is about a drunk. I was smitten with all things Lowry at the time, even though Ken Kesey told me quite firmly that Under the Volcano was “junior high.” But avant-garde? Dickinson’s avant-garde. Ashbery. Loplop. I think Don DeLillo’s avant-garde. No one’s caught up with what he’s doing yet. After reading that review, William Gaddis called and said, Oh, Joy, I’m so sorry. I can still hear his voice saying that. I hadn’t even read it yet. It was nasty, and it did succeed in shutting me up for a while. A few years ago that novel was reissued by a tiny press. I like the cover very much, with Goya’s Dog.

Now, wait. Let me ask—what do you think of the state of criticism in this country? Isn’t that a relevant question? There’s James Wood, of course, who deals only with the giants, whom he quietly, sonorously corrects. Other critics seem, I don’t know, to lurch from writer to writer, wanting to crown someone.

INTERVIEWER

I think of the Internet, the sheer volume. Cynthia Ozick wrote recently about the influence of this environment, all those Amazon customer reviews.

WILLIAMS

Who writes those?

INTERVIEWER

Anyone. People who may, in an earlier age, have written letters to the editor.

WILLIAMS

It’s one thing when it’s a restaurant. I mean, they can destroy a restaurant overnight. To do that with books?

INTERVIEWER

Your characters seem to struggle to interpret the world’s detritus, trying to make sense of ominous signs. A window opens for a moment, but then the window is shut. Is that a fair description of the writer’s consciousness as well?

WILLIAMS

I think the writer has to be responsible to signs and dreams. Receptive and responsible. If you don’t do anything with it, you lose it. You stop getting these omens. I love this little church group I go to. The other day we were talking about how God appears or doesn’t appear and how we’re nervous about seeing God, and it was all very interesting, but then somebody piped up, Well, I think God appears often during the day! We just don’t recognize it! For example, I was trying to find my name tag before the ten-thirty service. There I was with all the name tags, I just couldn’t find it, and then I looked down and it had fallen on the floor! I thought, There’s God! Telling me where it was!

You know what I told her? I said that it was really a large name tag. It was. It was huge. How could she misplace it in the first place?

INTERVIEWER

To speak of signs or interpretation suggests, at the very least, that there’s something unknowable at the heart of what you do. I asked you, before we started taping, whether you remember anything of how some of your most famous stories—“Train,” “Escapes,” “Honored Guest”—came to be written, and you looked panicked. You honestly can’t recall?

WILLIAMS

I find it so difficult to talk about what I do. There are those who are unnervingly articulate about what they’re doing and how they’re doing it, which, I suppose, is what this interview is all about. I am not particularly articulate, unnervingly or otherwise. I do believe there is, in fact, a mystery to the whole enterprise that one dares to investigate at peril. The story knows itself better than the writer does at some point, knows what’s being said before the writer figures out how to say it. There’s a word in German, Sehnsucht. No English equivalent, which is often the case. It means the longing for some- thing that cannot be expressed, or inconsolable longing. There’s a word in Welsh, hwyl, for which we also have no match. Again, it is longing, a longing of the spirit. I just think many of my figures seek something that cannot be found.

INTERVIEWER

And the writer? Are you trying to resolve that longing?

WILLIAMS

There’s a story about Jung. He had a dream that puzzled him, but when he tried to go back to sleep a voice said, “You must understand the dream, and must do so at once!” When he still couldn’t comprehend its meaning, the same voice said, “If you do not understand the dream, you must shoot your- self!” Rather violently stated, certainly, but this is how Jung recollected it. He did not resort to the loaded handgun he kept in a drawer of his bedside table—and it is somewhat of a shock to think of Jung armed—but he deciphered the dream to the voice within’s satisfaction, discovering the divine irrationality of the unconscious and his life’s work in the process. The message is work, seek, understand, or you will immolate the true self. The false self doesn’t care. It feels it works quite hard enough just getting us through the day.

INTERVIEWER

Your voice in the early work is lyrical, dense. After your first few books you began to write journalism, and your fictional voice seemed to transform along with it. It became looser, blunter, more comic. Using that voice, you wrote things like “The Killing Game” and “Save the Whales, Screw the Shrimp” for magazines with large, vocal readerships.

WILLIAMS

Those magazine essays did not require any stealth of execution. Unlike with the stories, where my real interest lay in illuminating something beneath or beyond the story itself, I could be forthright, headlong. I could write about real-estate developers, hunting, infertility treatments resulting in zillions of babies. It freed me so much, those nonfiction pieces. After “The Killing Game,” the NRA had everybody write to Esquire. They had a closet full of irate letters about that piece. The next editor was dealing with it years after it appeared. For one of the magazines, I wanted to write about the Unabomber, but I couldn’t get an interview, so I wrote about his cabin, from the cabin’s point of view.

INTERVIEWER

The Unabomber’s cabin, the pink Wagoneer in 99 Stories of God, the wayward fifty-dollar bill in Breaking and Entering.

WILLIAMS

The fifty-dollar bill. Plimpton hated that. I remembered being so pleased with myself, thinking, Boy, I’m really working here, it’s all coming together! He sort of frowned and said, You’re showing off.

INTERVIEWER

Around this time, you became an authority on the Florida Keys.

WILLIAMS

Random House was doing this series—Virginia, the Hamptons, the Keys. The Keys were still kind of strange and unspoiled in the eighties. I went around the state and wrote things down, but nobody talked to me. Nobody! I’d limp into these bed-and-breakfasts and people would snarl at me and not want to talk. I mean, honestly, it was terrible and I had no idea what I was doing. And it wasn’t edited, nobody edited it. Have you seen the afterword, the final edition, when I didn’t want to update it anymore? Here I am, worn out and saying how shitty everything in the Keys has become, and Random House just went ahead and put the afterword in there. Isn’t that amazing? That’s the only book I’ve ever made money from.

INTERVIEWER

Writing this nonfiction, you’d expanded your voice?

WILLIAMS

With the essays, I wanted to say, there was a lot of freedom bestowed. I felt I could address fecklessness, evil, even grief in a much more honest and emotional way than I could in stories. Which is somewhat contrary to my belief that what the short story, as a form, excels in is the depiction of solitude and isolation. Perhaps writing essays made my fictional characters more garrulous, desperate even, desperate to convey. So my stories became tighter and more restrained in style at the same time my characters became talkier, if that’s possible. Maybe it’s not possible. Maybe it’s not even true.

INTERVIEWER

Writers are desperate to convey their obsessions. They populate the subconscious. Jung and his inexplicable dream, for example.

WILLIAMS

I wonder if understanding the dream is really what must be done. Can we incorporate and treasure and be nourished by that which we do not understand? Of course. Understanding something, especially in these tech times, seems to involve ruthless appropriation and dismantlement and diminishment. I think of something I clipped from the paper and can’t lay my hands on. This peculiar aquatic creature who lives deep within the sea—it looked like a very long eel—came up to the surface, where it was immediately killed and displayed by a dozen or so grinning people on a California beach. Didn’t have a chance to evolve, that one. Curiosity by the nonhuman is not honored in this life. For many people, when confronted with the mysterious, the other, the instinct is to kill it. Then it can be examined.

INTERVIEWER

This might be a good transition into your focus on the natural world, its degradations, the lives of animals. You’ve often quoted Coetzee’s character Elizabeth Costello, who explained that her vegetarianism came out of “a desire to save my soul.” How did this part of your life begin?

WILLIAMS

I’ve been trying to think of this subject, my environmental, moral education. The philosopher Peter Singer’s book on animal rights in 1975 transformed the thinking of many people. Not enough. Now a person with a gluten allergy is honored more than a vegetarian. And these days we continue to suppress, ignore the horror, the cruelty, the evil of the slaughterhouse. Such a simple thing, to not take part in such evil, yet the carnage continues and we find it quite acceptable. We are complicit, materially preoccupied, spiritually impoverished, and technologically possessed. Look what we did to the Earth when it was green and provident. We’ll suck it to the bone with limitation’s necessities. Well, there’s always space. It’s depicted on the endpapers of our U.S. passports.

INTERVIEWER

Do you feel complicit? Do you write out of a sense of guilt?

WILLIAMS

Forgive me for the things I have done and for the things I have left undone. I may very well write out of a sense of guilt. I’ve spent my entire life doing this. Why am I not better at it?

INTERVIEWER

What can writers do, politically?

WILLIAMS

Possibly not much. An environmental writer, Derrick Jensen, says salmon don’t need more books written about them. They need clean, fast water and the dams to be busted up. Anyway, environmentalism has become thoroughly co-opted. Join the big groves and you’ll be gifted with a tote bag to carry and conceal all your good intentions. I wish Earth First! would rise again, but they were branded anarchists and terrorists and harassed by the FBI.

INTERVIEWER

Perhaps only Alice, in The Quick and the Dead, explicitly voices any of your political concerns.

WILLIAMS

Yes, but she’s a crazy girl with a missing front tooth.

INTERVIEWER

How did that novel begin? It stands out from the others. The canvas is bigger, first of all.

WILLIAMS

I wanted to write about someone who cared, and who cared very much about the nonhuman world. Then it seemed right that she should be young, mouthy, and uncharismatic. Of course no one pays her any mind whatsoever, and she’s ultimately outdone by an even younger girl, Emily Bliss Pickless, whose abhorrence of the system allows her to succeed in it, in a peculiar way. I remember looking up something in the dictionary and seeing this word, Corvus, that means raven. It’s also a small constellation. A perfect name. I suppose I did have high-minded objectives. There were lots and lots of characters, living and dead, totem animals, dismemberment, senility, regret, grief, love, all set in the battered, demystified, American desert. It became a rather funny book, finding hidey-holes from complete despair, I guess. It was a journey toward a novel I still hope to write.

INTERVIEWER

How would you describe that novel?

WILLIAMS

To return to the idea of the avant-garde, real avant-garde writing today would frame and reflect our misuse of the world, our destruction of its beauties and wonders. Nobody seems to be taking this on in the literary covens. We are all just messing with ourselves, cherishing ourselves. Andrew Solomon wrote a mega-successful nonfiction book titled Far from the Tree in which he ticks off every emotional, physical, mental, social disability you could possibly imagine and yokes them to true tales of actual practitioners or victims—though Solomon would never employ such a word—which he then bathes in a golden humanist light. We are all so special, particularly the very special, whose needs must be met. We are all so different and some of us are even more different, and this difference must be cherished and celebrated. The critics were ecstatic. What a hymn to diversity! No one spoke of how claustrophobic Far from the Tree was, the tree being utterly metaphorical, how narrowly and pridefully focused, how dismissive of a world outside the human. Cultural diversity can never replace biodiversity, though we’re being prompted to think it can. We live and spawn and want—always there is this ghastly wanting—and we have done irredeemable harm to so much. Perhaps the novel will die and even the short story because we’ll become so damn sick of talking about ourselves.

INTERVIEWER

You often seek the remotest solitude to live and work. What are your typical working conditions? Notebooks? Do you pack a typewriter?

WILLIAMS

I currently own seven Smith Corona portables, if that’s at all interesting, which it probably isn’t. My favorite typewriter is a palomino-colored Sterling that Noy Holland gifted me with in Amherst, Massachusetts. At home in Arizona, I don’t have a TV or Internet or air-conditioning. I’ve never even seen how 99 Stories of God appears to others, as Byliner produced them. They are as vapor to me. My old black Bronco has almost three hundred thou- sand miles on it. It’s traversed the country dozens of times. A great vehicle! My other ride is of a much more recent vintage—a 2004 Toyota Tundra with which I have yet to truly bond. I like old things. I almost never buy anything new.

INTERVIEWER

How does writing get done on the road?

WILLIAMS

Here in Wyoming, I sit and work and walk the dogs. I watch the thrilling ravings of Max Keiser on the RT channel. This TV has cable or a satellite, one or the other. I finally saw The Tree of Life through to its end on the Sundance Channel. Have you seen the ending? I did like everyone meeting up on the beach, although the last shot, of the field packed with sunflowers, seemed a little quiet. All I could think when I saw the field was genetically modified. I missed the glory, totally.

INTERVIEWER

What about the act of writing itself? Do you ever enjoy writing?

WILLIAMS

That nice Canadian writer who recently won the Nobel—beloved, admired, prolific. Who would deny it? She said she had a “hellish good time” writing. This could be a subject for many, many panels. Get a herd of writers together and ask them, Do you have a hellish good time writing? Mostly, I believe, the answer would be no. But their going on about it could take some time.

INTERVIEWER

You’re funny. You must know this.

WILLIAMS

Occasionally I can have a little fun or am pleased with an effect. The conversations between Ginger and Carter, for example, in The Quick and the Dead, or the Lord’s interactions with the animals in 99 Stories of God. But then I hear Plimpton again—You’re showing off.

INTERVIEWER

Who are some living writers you admire?

WILLIAMS

DeLillo is first among them. A writer of tremendous integrity and presence. Mao II is an American classic. So, too, is White Noise, though it’s been taught to splinters. His later works are fierce, demanding. His work can be a little cold perhaps. And what’s wrong with that? The cold can teach us many things. Coetzee I admire very much. On a lighter note, the Russians. Vladimir Sorokin and his crazy Ice trilogy. The short-story writer Ludmilla Petrushevskaya.

INTERVIEWER

Jane Bowles seems like a precedent for your voice.

WILLIAMS

Oh, I hope not. Two Serious Ladies is a confounding book. A ridiculous situation, or situations, unbelievable characters. The plot proceeds in the manner of crutches needing tips. She certainly doesn’t write in any “accepted style” of either then or now. Yet it’s a fascinating book, forever gathering up new and enthusiastic readers. It’s an unnerving book. Do we fear for this writer? The exoticism and tragedy of her life? Paul Bowles, Morocco, her unfortunate love interests, her stroke. She seems to know nothing about human nature, which may quite signify she knows a great deal. I find her refreshing, in the way that drinking vinegar is refreshing.

INTERVIEWER

You reviewed a recent Flannery O’Connor biography and noted her habit of reading theology to embolden her work. What’s the connection for you between religious thought and the writing life?

WILLIAMS

The Bible is constantly making use of image beyond words. A parable pro- vides the imagery by means of words. The meaning, however, does not lie in the words but in the imagery. What is conjured, as it were, transcends words completely and speaks in another language. This is how Kafka wrote, why we are so fascinated by him, why he speaks so universally. On the other hand, there’s Blake, who spoke of the holiness of minute particulars. That is the way as well, to give voice to those particulars. Seek and praise, fear and seek. Don’t be vapid.

INTERVIEWER

Your philosophy, your method, is to seek and praise, fear and seek, and don’t be vapid?

WILLIAMS

You think that’s too vague? Methods limit you as soon as you recognize them. Then you have to find another form to free yourself.

INTERVIEWER

Freedom—you’ve mentioned it several times. Is freedom why you spend so much of your life out in the middle of nowhere?

WILLIAMS

Yes, yes. Freedom is most desirable. Of course none of us are free. Our flaws enslave us, the things we love. And through technology we’re becoming more known to everyone but ourselves. What’s that phrase about certain writers being what the culture needs? Most writers just write about what the culture recognizes.

INTERVIEWER

Your last book, 99 Stories of God, takes the form of parables—koans, vignettes, almost poems, with forays into philosophy and theology. The Lord shows up on Earth a few times to mingle awkwardly. Was this subject or style freeing to you?

WILLIAMS

I’m going to do one more story about God. He’s really going to confide in me. Then I’m done.

https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/6303/joy-williams-the-art-of-fiction-no-223-joy-williams?utm_source=Jocelyn+K.+Glei%27s+newsletter&utm_campaign=6d1adb27b5-Newsletter_01_05_17&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_0d0c9bd4c2-6d1adb27b5-143326949

0 notes