#ignavus tema

Text

Language of the Regency: Modern Tema

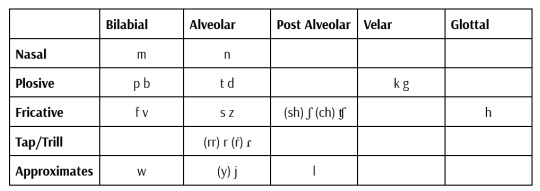

Phonetics and Phonotactics

Onset: m n k p ny ŕ ch sh h s th d g w p l rr b t

H Clusters: hw hŕ hl

P Clusters: pr

Nucleus: m n ny rr ŕ y k h v f l b w ch th sk

Coda: n t l ŕ ch

Vowels: a i e o u

A Clusters: aa ao ae au

| | | |

Word Order

Primary - SOV | Subject Object Verb

Ma in-rridi haku

lit. I the bird hunted

I hunted the bird

Secondary - SVO | Subject Verb Object

Ma haku in-rridi

I hunted the bird

Predominantly Head Initial Language

Nouns - Adjectives | Narru naŕa (white river (lit. river white))

Noun - Numbers | Lokal yun (two rocks (lit. rock two))

Noun - Genitives | Mao fisal fiwa (mother’s whiskers (lit. whisker of mother))

Noun - Relative Clauses |

Article - Noun | In rridi (the bird)

Demonstratives - Noun | Avi narru (this river)

Adjective - Adverb | rraheŕi wiwa (pretty stupid)

Yes/No Particles | Post-Sentence

Ma kimakaal, yami

I am coming, yes

Question Words | Post-Sentence

Ha otokaal, nyak?

Where are you going?

Proper Noun - Common Noun |

Modifier Order | opinion-number-material-size-color-purpose/use

Modifier Example

In sulil rreeŕi teŕ datayame piyuŕe

lit. the bowls pretty three wooden small

The three pretty small wooden bowls

Compounds | Adjective-Noun

Awataya (forest (lit. place (of)-tree))

| | | |

Noun Class System

Modern Tema retained the group-of-four nouns that initially formed their melting class system, with agreement emerging in both adjectives and articles. As Tema began to be formally recorded and studied by its speakers, with active lessons towards foreigners, they assigned proper names for the four classes.

Solar Nouns (-ŕu) The first noun class originally came from all things good and safe. Made of edible prey, safe and comforting things, familiar friends, close kin and things associated with day-time and toms, its other names are Sun Nouns, Red Nouns and Day Nouns. Regarding family members, swapping them into the Solar class is an indication of closeness or familiarity.

Pat ihŕaŕu (fresh prey) > Fresh, prey that is safe to eat

Hŕan sayaŕu (big deer) > a large, non-aggressive deer

Ka basu piyuŕu (my small den) > my small den that I love

Iŕa aŕa sanyaŕu (the bright sun)

Lunar Nouns (-sa) This second noun class is associated with the moon, contrasting the first class and is made of challenging or frightening things, ethereal feats of nature, intimidation, the night and mollies. It expresses a formal relationship with others and is often used to convey respect and deference to others when spoken.

Hŕan sayasa (big deer) > a large, aggressive deer, perhaps a stag

Ka mao chiŕasa (my kind mother)

Neaŕa sahwasa (a quiet night)

Aaku niskalusa (a careful hunter)

Lightless Nouns (-ye) The third class born from things of great suspicion, danger or prone to causing death or some form of sickness. It absorbed several locations from the previous location classifier that have long since been deemed ‘cursed’ or full of negative energy.

Amuk ayisiwaŕeye (a terrible weasel)

Shuniprri vachiye (a vile kinslayer)

Nyiŕ Choyikal Kaprru (The Skull Lands)

Ayoŕeye (poison (lit. lightless herb))

Mortal Nouns (-ŕe) Named as such to mark an obvious difference from the other three classes, the mortal nouns made of things constructed by mortal paws - being mostly condensed down as ‘tools.’

Chofi piyuŕe (a small pouch/satchel)

Nunei naaŕeŕe (a long tether/leash)

Nabo samaŕe (a hot pan)

Keyinaya malaŕe (an empty waterskin)

In addition to these basic methods of sorting words, Tema allows a little modification to appear on the noun itself to create a simple, concise identifier.

Hŕanuŕu (good/fresh deer (meat)) or ‘a safe or non-aggressive deer.’

Hŕanasa (scary deer)

Hŕaneye (bad/rotting deer (meat)) or ‘a dangerous deer that has killed.’

Listing prey animals while adding a class modifier is usually indicative of the animal being spoken of as prey, with the implication of ‘meat’ being announced while using a separate adjective indicates a living creature.

Hŕanuŕu sayaŕu (large deer meat) vs. Hŕan sayuŕu (a large deer)

Grammatical Number

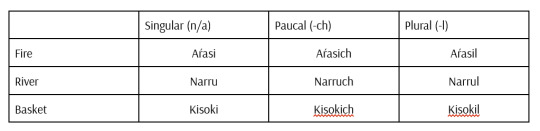

By now, Tema has officially adopted the paucal number into their paradigm, leaving the singular unmarked.

There's not much to say, so here are a couple of examples:

In aŕasil teŕ piyuŕu | The three small fires

In narruch piyusa | A few small rivers

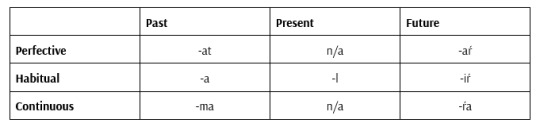

Tense and Aspect

The discontinuous, -mano expresses that an action or event is no longer true. For example;

Ma in asish matamano | I caught the fish (but I no longer have it)

In this case, the affix -mano implies that though the speaker had once had possession of the fish, this is no longer true. Perhaps the speaker dropped the fish while bringing it in, or they gifted it to someone after catching it. Whatever the reason, the speaker no longer has possession of the fish.

-sahwa (still, unchanging) is still in full effect here. As a reminder, this -sahwa forms the continuative aspect clarifying that an event is still ongoing at the current moment and at least in Tema, had likely been happening for a very long time.

No haku (They are hunt/are hunting)

No hakusahwa (They are still hunting)

In the first sentence, the hunters are merely hunting deer - the implication being that they’ve either left recently or the hunting is happening in a normal span of time. The second sentence implies that the hunters have been out for a long time, long enough to be worth noting or to be a cause of concern.

And of course, combining it with the habitual aspect (hakulisahwa) is still used to express disbelief or incredulity. With the loss of the noun classifiers, the difference between pejorative disbelief (exasperation, annoyance) and positive disbelief (amazement, awe) has become conveyed near exclusively through context and tone alone.

No hŕan hakulisahwa

(they are still hunting deer)

Can be meant in either a concerned way (they are still hunting deer (but they should be back by now)), in a way that expresses annoyance and frustration (they are still hunting deer (but we don’t need/want them to)) or in surprise and amazement (they are still hunting deer (even though there’s ample discouragement to)).

Often, the rest of the sentence is enough to convey which meaning is being brought up here:

No hŕan hakulisahwa e in niva koyun aamicheŕu

They are still hunting deer and the snow is getting heavier

Here, the speaker is mostly concerned with the safety of the hunters. The deer itself is unimportant, but the fact that they’re still hunting in in-opportune conditions.

Wi oto e no hŕan hakulisahwa

We are leaving and they are still hunting deer

In this example, the speaker is irritated by the hunters as their hunting is happening at a bad time. Likely, the group cannot leave the area before the hunters return, and their long hunting trip is holding everyone else back.

Omi ayeŕanit ihŕayiat ilk ŕi Menya e no hakulisahwa hŕan

That stag broke Menya’s leg, and he’s still hunting deer

And in this example, the speaker is impressed or incredulous by the hunter - Menya. A stag has previously introduced a higher degree of danger, enough so that the speaker would be inclined to believe that Menya would stop hunting deer for a while, but he did not.

Mood and Modality

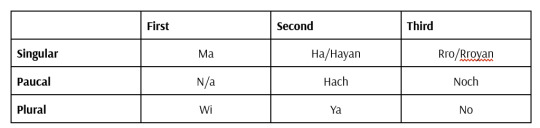

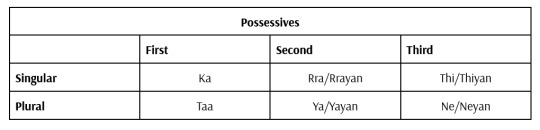

Pronouns

The basic independent forms of the basic pronouns have become entrenched in place although, a pair of new words have been attached to the second and third-person singular as a way of expressing formality:

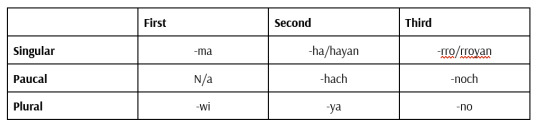

These words came from the association of the royal and noble families as divine guardians of the mortal people, coming from the sheyan (spirit). This change has also been reflected in the dependent markers:

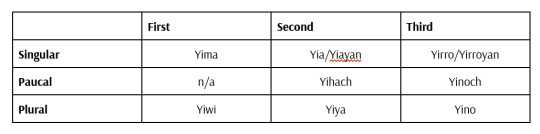

And of course, our example word in the form of yi (to see):

With this in mind, the independent forms are often interpreted as more formal or ‘proper’ speech, clarifying all of the individual parts. It’s sometimes considered ‘childish’ as it’s the way cubs and non-native speakers are first taught to speak the language before moving into the dependent versions.The dependent forms are then thus, viewed as casual or informal conversation.

Ma yanya haku iko ha

I enjoy hunting with you (formal)

Vs.

Yanyama haku iko ha

I enjoy hunting with you (informal)

Following along, the formal second and third personal singular forms are extremely form and imply that someone to talking to or about someone of great status, usually the royal or noble family. Interestingly, using the independent formal version is used of the crown heir and the king and queen, while the dependent formal version is used on everyone else in the royal family:

Ma yanya haku iko hayan

I enjoy hunting with you (formal/heiress or rulers)

Vs.

Yayama haku iko hayan

(I enjoy hunting with you (informal/nobles, non-inheriting heirs)

Another distinction is the use of both dependent and independent markings when trying to emphasize something:

Ma yanyama haku

I enjoy hunting

This sentence for example would read as ‘I really enjoy hunting’ or even ‘I, personally, enjoy hunting’

Articles and Demonstratives

There is no indefinite article in middle mogglish - all unmodified nouns are considered to be indefinite by default:

Maŕo (cat, a cat)

Owninuŕ (rat/mouse, a rat/a mouse)

Chovu (fox, a fox)

The definite article has now been settled into multiple forms that change based on noun class:

Iŕa maŕo (the (safe/familiar/) cat)

Hiŕ maŕo (the (intimidating/unfamiliar) cat)

Nyiŕ maŕo (the (scary/dangerous) cat)

Saŕu sarril (the den)

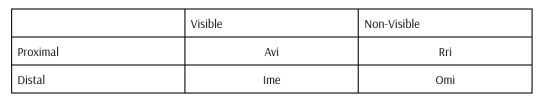

The demonstratives remain similarly unchanged.

Proximal things refer to nouns close to both the speaker and the listener while distal are things far away from the speaker but often close to the listener.

Avi iŕu narru

(this river (near us))

Vs.

Ime iŕu narru

(that river (near you))

In this example, both of the demonstratives used also fall under the ‘visible’ column - which means the speaker can see the river. This does not however, mean the listener can see the river - the visible and non-visible distinction applies to the speaker alone and sometimes is used as a short-hand when a lost or difficult to find thing has been located:

Avi narru!

((I found/I can see) this/a river (near us))

On the other side of things, non-visible things are - as one might guess - things that the speaker can’t see. It’s also of course, used to remark upon something that the speaker isn’t aware of the location of something.

Rri iŕu narru

(this river (that I can’t see/can’t find))

OR

Omi iŕu narru

(that river (that I can’t see/can’t find))

#the languages of ignavus#the sky regencies#ignavus tema#constructed language#conlang#conlanging#I had/have ideas for grammatical mood but eh...

7 notes

·

View notes