#in my head charles and edwin died in college

Text

just so everyone knows: im refusing to engage with the idea that edwin and charles are actually minors

there is no universe where any of these characters are realistically 16

#dead boy detectives#in my head charles and edwin died in college#bc yeah if the narrative wants them to be minors bc of Plot reasons thats fine#but also go fuck yourself if you think im buying for a SECOND they are supposed to be 16 y/o HIGH SCHOOLERS#if crystal and niko are supposed to actually be in high school the cops are getting called#but seriously even the narrative doesnt treat them as minors so idk why people would see them as minors#they're minors for the SOLE PURPOSE (in the show) to have the night nurse lady be there for the narrative and overarching plot#like thats it thats the only reason the plot has them-on their face-be minors#also i love the idea of edwin being over 100 years old but telling everyone he's just a boy bc 1. hes repressed and 2. he thinks its funny#also saying they're eternally 16 is like saying a vampire is only 16 when they've been around for hundreds of years

13 notes

·

View notes

Video

undefined

tumblr

“YOU WILL BE FOUND” NATIONAL COLLEGE ESSAY WRITING CHALLENGE 2021 | DEAR EVAN HANSEN

DEAR EVAN HANSEN

“You Will Be Found” National College Essay Writing Challenge 2021

In partnership with Gotham Writers Workshop and the Broadway Education Alliance, DEAR EVAN HANSEN invited 11th-grade and 12th-grade students across the country to write a college-application style essay that describes how they channeled “You Will Be Found” to ensure those around them were a little less alone over the last year, or, alternatively, a moment where they found comfort in connection.

WINNER:

Nearly 4,000 high school students across America wrote about impactful ways they stayed connected with others over the last year and we're delighted to announce Maxwell Silverman of Chicago, IL as the winner of the 2021 "You Will Be Found" National College Essay Writing Challenge and the $10,000 scholarship.

In June 2021, Maxwell graduated from Lane Tech High School in Chicago with plans to attend Boston Conservatory at Berklee, focusing on a degree in Musical Theatre.

FINALISTS:

Seth Gorelik, Bellmore, NY

Mira Kwon, Los Angeles, CA

Anna Cappella, Pittsburgh, PA

Semira Abdus-Salam, Rosedale, NY

Filgey Borgard, Brooklyn, NY

Lauren Escarcha, Orlando, FL

Kacey Feth, Union, MO

Paige Foltz, Stephens City, VA

Sarah George, Chesterfield, MO

Vincent Gerardi, Hauppauge, NY

Ariane Lee, Syosset, NY

Allison Lierz, Omaha, NE

Megan Luong, New York, NY

Kimberly Manyanga, Billerica, MA

Orla Grace McCoy, Raleigh, NC

Lucy Meola, New York, NY

Sunaya DasGupta Mueller, Palisades, NY

Liv Ollestad, Issaquah, WA

Liana O'Rourke, Downers Grove, IL

Isaiah Register, New York, NY

Sydney Schneider, Los Angeles CA

Ysanne Sterling, Centreville, VA

Madeline Wiest, Peoria, AZ

Samantha Williams, Providence, RI

Laura Yee, New York, NY

FINAL ROUND JUDGES:

Kelly Caldwell, Dean of Faculty, Gotham Writers' Workshop

Logan Culwell-Block, Director of PLAYBILLder Operations and Community Engagement, Playbill

Will Roland, Actor, Dear Evan Hansen Original Broadway Cast Member

Crystal Su, Program Manager, The Jed Foundation

Ekele Ukegbu, 2019 Jimmy Award Winner

READ MAXWELL’S FULL ESSAY:

Gram·pun·cle [geram-puhn-cuul] n. A gay man who formerly dated your grandmother only to later come to terms with his sexuality but still stay in the family to take care of your mother and aunt growing up.

Alan Palmer was my Grampuncle. When my cousins and I were younger, we couldn’t figure out what to call him. He was our grandpa in terms of age and raising our mothers, but he functioned more as the classic “fun gay uncle”, so we settled on a combination, Grampuncle. While we all had amazing relationships with Alan, mine was special. I have known Alan and his husband, Bill, since birth (making them the first ever gay couple I knew in my life).

Growing up and struggling with my sexuality, I was always able to look up to them to show me that true love really does have no boundaries. I will never forget, in 2015, standing inside the Michigan courthouse beside Alan as he and Bill exchanged vows and got married. They showed me, a young, insecure gay boy, that there was a place for me in the world and that I had a future to look forward to filled with love and joy.

Along with that joy, there eventually came some pain. Alan was diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer in the early spring of 2020. A week or so after the diagnosis, the world fell into a global pandemic. Those first few months were intense. I heard the horror stories from Alan of how scary it was going into the hospital for rounds of chemotherapy with people who had the Coronavirus sitting in the next wing over. Being constantly in and out of the hospital he was a risk to others, and the lung cancer made almost everyone else a risk to him. With the exception of his husband, he was fully alone.

Alan did not admit to his loneliness and pain. He did not want to feel like a burden, but after talking with Bill and hearing how Alan was truly feeling, my family began to make the hour and a half drive from Chicago to Michigan almost every other week to visit. We brought Alan a pop-up gazebo and some fancy sun hats to protect him (with the radiation he could not be in the sun for more than a few minutes at a time), and we would sit in the backyard just talking and laughing for hours until Alan’s body would give in to the exhaustion and he had to go inside.

As his birthday approached, I racked my brain thinking of something special to do for him. I thought back to a video I saw online toward the beginning of the pandemic and decided to make a “hug shield”. What better gift to give than a loved one’s embrace during the pandemic? Using a clear painter’s tarp, I cut arm holes and taped together closed arm sleeves. It took a good few hours, but I finally figured out a design that allowed for full protection on either side of the hug. On the day of his birthday, we packed up the car and headed to Michigan.

After talking and eating cake, it was time for the surprise. As we pulled the shield out and hung it from the gazebo, Alan did something I had only seen at the courthouse; he cried. I had the honor of the first hug, and as I slipped my arms into the sleeves Alan and I held each other and cried together. He pressed his forehead against mine through the plastic and in between sobs he said to me, “I am so proud of you.” I knew this was our final goodbye. When Alan died the next week, I knew he went in peace. He had felt my embrace through the shield of love.

SEMI-FINALISTS:

Bailey Andera, Thousand Oaks, CA

Arianna Arroyo, Brooklyn, NY

Alexis (Lexi) Berganio, Honolulu, HI

Avery Bielski, Los Angeles, CA

Henry Boemer, Villa Rica, GA

Isabelle Bulmahn, Imperial, MO

Jane Butera, Phoenixville, PA

Mia Cashin, Norwell, MA

Sean Choo, Rancho Palos Verdes, CA

Zuri Clarno, Columbus, OH

Lydia Corcoran, Apalachin, NY

Cody Coyle, Winter Park, FL

Anna Dai-Liu, San Diego, CA

Alexander Guerrero Diaz, Richmond, VA

Isabella Dufault, Irvine, CA

Edwin Ellis, Atlanta, GA

Laurel Emanuel, Raleigh, NC

Aubrey Fisher, Cobden, IL

Sunny Fong, Brooklyn, NY

Sarah Galatoire, Houston, TX

Zhao Gu Gammage, Wyncote, PA

Sarah Gomez, Anaheim, CA

Rachel Gray, Cleveland, OH

Jameson Huge, Chicago, IL

Sarah Grace Hutchinson, Alpharetta, GA

Catheryn Ibegbu, Dearborn, MI

Nicole Jo, Andover, MA

Kelsey Johnston, Prince George, VA

Gabrielle Kashorek, Avon, NY

Samantha Kern, Akron, NY

Nicole Kowalewski, Sykesville, MD

Anne Lee, Edison, NJ

Amelia Lin, Mukilteo, WA

Judianne Meredith, River Vale, NJ

Rabi Michael-Crushshon, Minneapolis, MN

Geneva Millikan, Maumelle, AR

Samantha Moy, Long Island, NY

Shaakirah Nazim-Harris, Amityville, NY

Eleanor Neal, Springfield, VA

Sofia Ochoa, Camarillo, CA

Basilia Oferbia, Brooklyn, NY

Annika Olson, Rathdrum, ID

Kaden Polt, Osmond, NE

Shreeyamsa Poudel, Federal Way, WA

Noah Robie, South Berwick, ME

Zainely A. Sandoval Martinez, Dorado, PR

Devyn Schoen, Eldred, PA

Yusra Shaikh, Edison, NJ

Gabrielle Shockley, Egg Harbor Township, NJ

Ava Sklar, Brooklyn, NY

Mia Sunday, Sammamish, WA

Christina Unkenholz, Smithtown, NY

Emilia Valencia, Portland, OR

Brianna Wallace, Fredericksburg, VA

Charles Wang, West Hartford, CT

Daniel Joseph Weispfenning, Ridgewood, NJ

Jennifer Wheeler, Reading, MA

Virginia Zanella, Collierville, TN

Alessandra Zepeda Ortiz, Los Angeles, CA

Anna Zhang, New York, NY

Daniel Zhang, Cortland, NY

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Polly Nichols', the seafaring man and the murder of Annie Smith

The day of Mary Ann “Polly” Nichols funeral was held, on Thursday September 6th 1888, the Irish Times published:

“THE WHITECHAPEL MURDER

Up to midnight no further information has transpired respecting the Whitechapel murder. Whatever information may be in the possession of the police they deem it necessary to keep strictly secret, but considerable activity is quietly being exercised in keeping watch on suspected persons. It is believed that their attention is particularly directed to two individuals, one a notorious character known as "Leather Apron," who has been the terror of women in the neighbourhood for some time, and a seafaring man who has already stood trial for a crime not far short of murder“.

On the JTR Forums it was proposed a suspect.

Between April 26th and May 15th 1888 many newspapers reported the Lea-Bridge Mystery. The body of Elizabeth Ann Smith, a 25 year old girl, was discovered near a broken umbrella with the handle missing in Lea Bridge (Leyton, London) by Edward Hatley and the Police-Constable Yates about 150 yards of the White House beerhouse. She had been missing for several days.

Annie Smith, as she was known, was the daughter of Mr. Albert Smith, builder who resided at Hemsworth-street, Hoxton (a district in North East London, part of the London Borough of Hackney, England) whom she lived with, along with her mother, two brothers and six sisters. She was unmarried and worked as a machinist for Messrs. Itobins, of Hoxton-street, drawing a weekly salary.

Her fiancé, a carpenter named William Steel who lived in the same street as her and courted her for six years, said he left her when he found her standing alone in a bar. He slapped her and left, but this was some days before she died and apparently the fiancé was cleared of suspicion.

On Saturday, April 21st 1888, Annie left to Lea-Bridge, which was apparently a hot spot for the working class in the East End. There were many pubs, coffee houses, eateries, live music , and a large stage for dancing. Annie was seen by many people dancing with a well-dressed young man of about 19 or 20 whom she may have arrived with. Shortly thereafter, she was found propped up outside a coffee house. The owner carried her in and it took him about 15 minutes to revive her. He felt she had been drugged by someone who then sat her in front of his shop. He made the observation that she smelled strongly of Brandy and snuff.

When the girl awoke she spoke strong language about some unnamed man. She also mentioned she was heart-broken, because of her recent break-up. A little while later, she was once again seen with this well-dressed young man, and once again was found in a ‘stupid state’ as though drugged. This suspicious young man was not seen after this time and remains unidentified.

Following this, witnesses saw some men talking with Annie and behaving strangely, grabbing at her dress, and seeming to pass something from hand to hand. When called out, Annie checked her purse and found her wallet missing. Had the young man from earlier stolen it while she was drugged? These young men stated they were simply trying to keep her dress from dragging in the mud. One was George Anthony, described as a “bargeman engaged on the river.” He stated that he and a friend walked with Annie a short ways but then left her when Charles Cantor (or Contor, Carter) came along. Annie said she was heading home. Charles Cantor was found and stated that he had walked with her a short ways then she went on alone. The area these men say they were at and the route Annie would have taken home were far away from where her body was discovered. She would have had to walk across a field and then into the marshes.

Sadly, a week was lost in finding her. On Sunday the 22nd April 1888, when she had not returned home, Annie’s mother and sisters went about doing their own detective work, tracking her to the Lea-Bridge area, finding out who she’d been seen with, and even speaking directly with George Anthony and others involved. They then went to different police stations, but none of them wanted anything to do with it. The mother then went to the Worship Street magistrate and spoke with Mr. Hannay, who made sure she got publicity in the Times of April 26th. After this, the lax men of J Division were forced to take action. By the time they found Annie’s body she had been in the marsh waters for a week and half of her face as well as one arm had been eaten away by water rats.

The police were convinced a murder had occurred and believed the girl had been ‘brutalized’. They felt the umbrella played a part. Emma Elizabeth Smith’s name was never mentioned (she'd been attacked on March 3rd and died the following day).

It was stated in the press that the umbrella was identified as belonging to Annie, but her sister Amelia Smith swore she left home without an umbrella and had never possessed that particular one. It was found some distance from her body, but a witness at the inquest said the body could have originally been in the marshes near the umbrella and would have drifted away over the course of the week. For all we know, the umbrella could have been discarded by anyone at any time simply because it was broken. But it’s interesting that the missing handle was not found.

Doctor Charles Taylor Aveling, divisional surgeon of police, who had had over twenty years' experience in the profession by 1888, and who was a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, a Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries, and a Master of Surgery and MD from the University of London, conducted post-mortem. He performed a comprehensive examination, including examinations of the internal organs and a careful search for external marks of violence, before reaching the conclusion that death had indeed occurred by drowning.

The police ended up arresting Charles Cantor and George Anthony for the crime and stated that there were two other men they were looking for as well, although charges were not pressed against the last two ones. The inquest took place in Hackney (London), and its jury, presided over by Wynne Edwin Baxter, could only determine that Annie had been ‘Found Drown’. The week in the water had taken its toll. There appeared to be much bruising about her, but the doctor Aveling felt that could also have been caused by the time in the water. He found no evidence of recent intercourse, but that would have been an impossible feat anyway after a week in the water, unless her tissue had been significantly torn, which apparently it hadn’t.

The police proceeded with their case against the young men. Charles Cantor was eventually released on bail, because there was no evidence against him at all, the judge felt. George Anthony did not get off so easy and had to wait in jail until the time came when, lacking any real evidence against them, or even proof that the girl had been murdered, both Cantor and Anthony were let loose with fines.

There's more information about the inquest at the London Magnet Newspapers Archive.

George Anthony could have been the ‘seafaring man’ that the police was looking for regarding the Polly Nichols’ murder, because he was a bargeman, ‘who has already stood trial for a crime not far short of murder,’ and much to police chagrin, was let go. Both the Annie Smith and the Mary Nichols cases were J Division and investigated by the same men.

More info on Find My Past website - April 1888 newspapers.

More info on Find My Past website - May 1888 newspapers.

#Mary Ann Nichols#Polly Nichols#Mary Ann Polly Nichols#Elizabeth Ann Smith#Annie Smith#1888#1880s#victim#Lea Bridge#Lea Bridge Mystery#George Anthony#Charles Cantor#Charles Carter#Charles Contor#Mr Hannay#Dr Charles Taylor Aveling#dr. Charles Taylor Aveling#dr Aveling#dr. Aveling#doctor Charles Taylor Aveling#doctor Aveling#Wynne Edwin Baxter#victorian era#victorian england#Victorian London#victorian crimes#victorian murder#murder victim#Irish Times#article

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nana

I lost my grandmother early in the morning on New Year’s Eve. Nana was loving, funny, and intelligent; she taught me how to read and how to love reading; she took me in her arms when I was upset; she showed me time and time again that I would never defeat her in Scrabble; she forgave me even when I did not deserve it; she stayed up past midnight to say, "Hey, Teach!" and enjoy champagne with me when I got my job. She changed the lives of those whom she met and loved and made me the person I am today.

She was my best friend.

Nana loved being a mother, a grandmother, and—as of just a few months ago—a great-grandmother more than anything else in the world. As we gathered by her bed and held her hand as she began to let go, “To the Lighthouse,” one of her favorite books, seemed to sing from the shelf. Nana’s writing adorns the opening page. She remarks how the book improves upon each reading, and then writes: “Philosophy is what we don’t know, want to know, tried to know—but only God knows.” Flipping through the worn pages, I traced her annotations throughout Virginia Woolf’s masterpiece. It is clear and unsurprising that Nana loved Mrs. Ramsay and Lily, for she connected with so many of the women’s interior monologues about emotional understanding and frustration. More than any other, though, one early passage stands out. Unlike many other passages with marginal explanations, Nana underlined and starred: “She would have liked always to have had a baby. She was happiest carrying one in her arms.” Just a few days before she died peacefully in the early morning, Nana held her first great-grandchild in her arms and laughed: she was happier in that moment than she had been in a long while.

Nana paused over—and could not find words for—a passage in which Mrs. Ramsay reflects on why children grow up so quickly, on why they seem so determined to rush toward the trials and pain that come with age, on how she wishes she could freeze time to protect them from the vicissitudes of fortune. I remember how clearly Nana echoed both the wishes and the frustrations of Mrs. Ramsay when Yaya, my mother’s mother, was diagnosed with stage IV ovarian cancer: “Sugarfoot, I wish I could take all the pain and the sadness for you—I wish that I could shield you from loss. But I can’t. Because that’s life.”

Nana knew that life and love lead inevitably to death and loss. But she also knew what we can learn from “To the Lighthouse”: not just that life and death, like love and loss, are inextricably bound together, but that, more importantly, loss and continuity coexist within our hearts and memories. Love has within it the power to defeat time. In one of my favorite poems, John Donne reflects on sickness and death:

Whilst my physicians by their love are grown

Cosmographers, and I their map, who lie

Flat on this bed, that by them may be shown

That this is my south-west discovery,

Per fretum febris, by these straits to die,

I joy, that in these straits I see my west;

For, though their currents yield return to none,

What shall my west hurt me? As west and east

In all flat maps (and I am one) are one,

So death doth touch the resurrection.

His doctors surround his bedbound body and map out his ailments like constellations across the cosmos—and all see that his sickness points toward the setting of the sun in the west as surely as the North Star guides sailors at night. Donne reminds us, though, that flattened maps are misleading: for the further west one goes, the sooner one arrives in the east. Just so, he writes, death does not mark the end of love, but the continuation of it.

Like the effervescent Mrs. Ramsay, who dies suddenly and unexpectedly and unexplainedly in the middle of the night, Nana has died. And like Mrs. Ramsay, Nana will never really be gone. For, just as Arthur Hallam speaks once more to Alfred, Lord Tennyson as the poet turns over an old letter from his dear, dead friend, Mrs. Ramsay appears to Lily in a moment of sublime love and memory:

“Her heart leapt at her and seized her and tortured her. ‘Mrs. Ramsay! Mrs. Ramsay!’ she cried… Mrs. Ramsay—it was part of her perfect goodness—sat there quite simply, in the chair, flicked her needles to and fro, knitted her reddish-brown stocking, cast her shadow on the step. There she sat.”

Nana will be a wonderful part of all of us forever. Near the end of her life, Nana told the loving family gathered around her bed: “It’s time for me to go home.”

“Home” probably resembles her enchanted childhood, for the love that she gave us was the love that had surrounded and defined her life: not a day of her young life went by without visits from and to doting uncles, caring aunts, trifling cousins, and those familial taskmasters who never let little hands sit idle. Nana was the second child of Lee Roy and Alberteen, who had three daughters and one baby boy, John Leroy, whom the girls simply adored—and spoiled. From her father, Nana received a twinkle in her eye that never dissipated. Family meant everything to him, a trait that he passed on to his own children and grandchildren. From her mother, a gifted schoolteacher, Nana learned to love literature and poetry. Nana admired her mother’s intellectual curiosity, which had often landed her in hot water as a young girl “working” on a ranch: Teenie loved to read, but simply hated to churn butter. Teenie would spend all morning reading in the light of dawn, but always with open ears: whenever she heard somebody coming, she would hide the book under her apron and start churning away.

Many of Nana’s fondest childhood memories were of her visits with her own grandmother, a great student of the Bible named Zemma Yett. “Oh, here are my girls!” Grandmother Zemma would cry whenever Nana showed up with her sisters, Billie Marguerite and Nora Lanelle. Evenings on the screen porch were filled with the nighttime sounds of Texas and Zemma’s intonations of Scripture. For much of Nana’s childhood, Zemma read by the light of a kerosene lamp—until one day, when Nana watched from her lap as President Roosevelt’s trucks wove electrical wires throughout sleepy Florence, Texas like thread through a loom as part of Rural Electrification.

Nana grew up in a Texas that no longer exists: a verdant and lush place defined by neighborly care and compassion. Texans of all backgrounds came together around the porch of her father’s grocery store, the gathering place for the neighborhood. As the sun went down, neighbors would sit around and tell stories or listen to the radio. Nana recalled with pleasure the excitement of the entire town listening to the bout between Max Schmeling and Max Baer—and remembers how the town would grind to a halt whenever Joe Louis, “the best of all,” stepped into the ring.

But with World War II came rationing, the end of the family grocery, and loss: two of Nana’s cousins joined the Air Force but did not live to see peace. Any romanticizing of war a young girl might come to believe in in the shadow of the Alamo died alongside Edwin and Charles, who loomed in Nana’s memory as the handsome man with shining cowboy boots and jodhpurs—not as the bloated body that washed ashore when his plane went down. Nana, Billie, and Nonie spent afternoons anxiously awaiting the local newspaper’s updates of war casualties and kept tearful track of the losses in their yearbooks. But the dark clouds of violence across either ocean brought Nana closer to literature and poetry.

Literature brought with it both balm and escape, and, at college, Nana fell feverishly in love with Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. She studied those Victorian works alongside Professor A. J. Armstrong, the head of the English department at Baylor, and became his academic assistant. Annotations in her neat-yet-illegible cursive sprawl across every single page of her textbooks; when space proved too tight for all she felt about her favorite poem, “Pippa Passes,” she inserted additional leaves.

She was working for the newspaper on a story about Christmas celebrations for soldiers when she interviewed about the handsomest man she had ever laid eyes upon: James MacDonald Werrell, who, forty years later, would be called Papa. Papa had returned to Texas, where his father was stationed at Fort Hood, to recover from a debilitating injury received during the Battle of the Bulge and to finish college. Although they fell for one another quite quickly—he was charming; she was witty—Jim fell out of touch over the Christmas holiday. Lee Roy did his best to comfort Nana, but she was broken-hearted.

And then, at long last, the phone rang. Nana gleefully accepted Papa’s apology—he had been on vacation with his parents, who, being nearly as cheap as he was, would not tolerate a long-distance telephone call no matter how in love he claimed to be—and hung up the phone in the kitchen only to find that her father had disappeared. Her mother stood next to the pantry door with her ear flat against it. As Nana walked toward her, she, too, heard her father’s crying: “Don’t worry, sugarfoot,” Alberteen whispered to her daughter, “Daddy just knows you’re going to be married now. He doesn’t want you to leave.”

They were married on December 20, 1947 and honeymooned in San Antonio in Papa’s yellow Jeep. Papa’s parents were not at the wedding both because they were stationed in Paris and because there was little love lost between in-laws: Angus Werrell was a Colonel in World War I, while Lee Roy had been a private. “It’s no man that blows a whistle,” Lee Roy remarked about commanders who stayed behind in trenches and sent men over the top and to their deaths. When Papa finished his studies at Baylor, he and Nana worked as fire lookouts in Colorado parks before going on a second honeymoon to visit his parents in Europe.

Nana saw many of the most beautiful sights in the world for the first time, while Papa saw them again, but in a vastly different light: with no heavy rifle, no wet socks, no constant vigilance or fear. Nana and Papa, alone in the Sistine Chapel for an hour, lay down on the floor to look up at the ceiling, then illuminated only by candlelight. They held hands through the streets of Paris and enjoyed picnics throughout the Austrian countryside—except when Jeanne, Papa’s sister, packed the food and placed the ham next to the petrol tank in the trunk of the car.

Nana continued her love affair with the world of art when she and Papa moved to New York City upon their return to the United States. In particular, Nana found herself under the spell of Bidu Sayão’s voice. Growing up, she had only ever heard the voice of Amelita Galli-Curci on the wind-up Victrola at her grandmother’s house, and so nothing prepared her for the clarity and beauty of the soprano singing Mimi in “La bohème,” Gilda in “Rigoletto,” or songs of her native Brazil. Papa’s days were filled with classes at the Columbia School of International Affairs, during which time Nana combed the hallways of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and his evenings were dedicated to practicing his German nightly with their landlords, Josef and Emma Ledwig. But Nana, a natural learner, picked up the language faster and more fluently than Papa; more than seventy years later, Nana could still recite Goethe’s “Der Erlkönig” from memory.

Papa joined the State Department following his graduation—work that brought Nana and Papa and their first baby, James MacDonald Werrell, Jr., then just a few months old, to what was then called Siam. While Papa conducted spook-work, Nana walked baby Jamie hurriedly away from prowling Varanus monitors, visited temples, and became the most frequent customer at C. J. Chan & Co., an English bookshop in downtown Bangkok, where she discovered the works of Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Upon their return to the United States, two sons—William Gresham Werrell, my father, and Timothy Savage Werrell—shortly followed their older brother into the world. And that was just the beginning of her adventures.

Nana lived to be so old in large part because she stopped driving. Like my high school English teacher Mrs. Chanson and so many other Southerners, Nana did not drive well, but instead casually: she did not always bother to open the garage door before reversing, for instance. While this might seem to suggest that she was just another little old lady from Texas, Nana was a political firecracker. She named her favorite dog, a territorial Jack Russell, after Lady Jane Digby, whose sex life created diplomatic tidal waves across two continents. She hated Viagra commercials with a passion because she believed they promulgated unhealthy and misogynistic views of sex: “They imply that it’s all up to the man: as soon as the man is ‘ready,’ one is supposed to drop everything one is doing to accommodate him. But what if I have a casserole in the oven?”

Indeed, one of the drawbacks of living for close to a century, Nana remarked this past Christmas, was that she had lived long enough to grow ashamed of Texas: her heart broke watching the most violent and vituperative voices attempt to speak for Texas and redefine Texan values. She loved her little brother so much that she could tolerate his support of Nixon—even when her sons and husband could barely stand to be at the dinner table with him. But politics changed, and so did her patience. Because nothing was dearer to Nana than her family, she knew in her heart that children belong in the arms of their loving family—not in cages. She could not abide hatred or vitriol; she could not understand why anyone would knowingly embrace cruelty, ignorance, or bigotry.

Driving to Charleston after leaving her now-empty home, I remembered the weeks she spent living with us and sleeping in my bedroom. We both kept one another awake with chatter and with snoring. During those late nights—Papa was in the hospital at the VA, reliving the Battle of the Bulge over and over again—we looked up at the phosphorescent stars on my ceiling and talked about school, books, friends, Papa, and memories.

I’ll always hear her voice.

0 notes

Text

September 2019

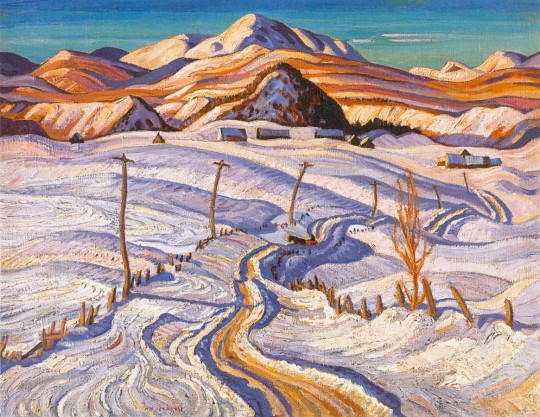

Winter Morning, Charlevoix County -- A. Y. Jackson, 1933

Dear Friends,

The theme of this edition is vision. Fatherless at age 12, the young A. Y. Jackson apprenticed to a lithographer in Montreal and quickly realized he did not want to spend the rest of his life designing soup can labels. He had a vision, hopped a freighter and studied art in Paris. On his return he knew he wanted to dedicate his life to art.

We now remember Jackson as one of the co-founders of the Group of Seven in Toronto, and the equally influential Beaver Hall Group in Montreal. Jackson and his friends in both groups were determined to create a new artistic vocabulary that was distinctly Canadian, and not derivative of our European mother countries. And they did!

I first encountered the magic of Quebec’s Charlevoix County when I was 12. My Queen’s professor father took me out of school in late spring of my grade eight year and said he was going to take me along on an annual business trip that would take us to Quebec City, Baie St. Paul, Murray Bay (now La Malbaie), Tadoussac, Baie Comeau, Seven Islands (now Sept Isles) and all the way up to Wabush and Labrador City.

Baie St. Paul is in the heart of Charlevoix, where the Laurentian mountains tumble down spectacularly into the tidal waters of the St. Lawrence. The air is salty and luminous, like the south of France. The hills are so steep, the region used to be known as Little Switzerland (La Petite Suisse). As many of you know, the biggest and best skiing in the east is at Le Massif, a 15 minute drive down Highway 138 from Baie St. Paul. I have been going there faithfully every winter for the past 25 years.

You may not know that part of the charm of Le Massif is that its visionary Cirque du Soleil co-founder and owner, Daniel Gauthier, saw to it to name a number of the resort’s runs after famous Charlevoix artists. It is a very special thrill to make fresh powder tracks in the company of René Richard, Marc- Aurèle Fortin, Clarence Gagnon and Louis Tremblay.

This summer, I retraced some of the steps of that long ago voyage with my father. I hadn’t been in Baie St-Paul other than in the depths of winter for close to 60 years, ahem. It is still a teeming art colony hugging the St. Lawrence, with colourful galleries, bistros and auberges lining its one main street.

Lest you forget, the city fathers have wisely erected bronze busts of about a dozen of the artists who put Baie St. Paul on the map. The four from Le Massif are joined by the likes of Jean Paul Lemieux; André Biéler (who taught at Queen’s beginning in 1936 and became the first director of the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in 1957); my old Montreal ad agency boss and Charlevoix artist Claude Le Sauteur; the godfather of the Beaver Hall Group and mentor to A. Y. Jackson, William Brymner; the folk artists Blanche and Yvonne Bolduc; and the inimitable A. Y. himself.

High tide in Baie St. Paul with Le Massif in the background

Dad said he met A. Y. once on his North Shore travels. I can’t remember what he related of that encounter, but I recall that he was impressed. Who wouldn’t be impressed with an artist who spent so much time tramping through the deep snow in the depths of winter in order to capture the perfect Charlevoix light that the locals dubbed him: Père Raquette (Father Snowshoes)?

One of Jackson’s greatest gifts was his ability to connect with fellow artists and lead, without basking in the limelight. Being bilingual, and presumably to some extent bicultural, it was A. Y. who bridged the divide between the anglos in Upper Canada and the French Canadians memorialized in the ski runs of Le Massif. This is what he is recognized for in the plaque below his bust in Baie St. Paul. It was Alexander Young Jackson who coaxed and seduced his brethren in Toronto -- e.g., Edwin Holgate and Arthur Lismer -- to pack their bags and easels and join in the creative ferment of Charlevoix. Equally, he promoted Quebec artists in Toronto, particularly the Beaver Hall Group members, from his perch in the Group of Seven.

§

I think my father had a vision for his 12-year-old son when he took me on that trip down the North Shore so many decades ago. Without ever saying it out loud, he must have wanted to impart to me the romance of French Canada. The first night in Quebec City, gazing down at Lower Town and the river from Dufferin Terrace with the Chateau Frontenac behind us, Champlain’s statue beside us, and the Plains of Abraham to the west, was enough to do that.

As I see it now, Dad also wanted to draw my attention to the kind of people he admired, the doers, creators and builders. He didn’t call them visionaries. He liked to talk about examples as we came upon them. Champlain fit that category. And A. Y. too. When we reached Baie Comeau, and passed a bronze statue in the centre of town of a man paddling a canoe , Dad was quick to tell me that it was Colonel Robert McCormick, the former publisher of the Chicago Tribune.

McCormick was an adventurer and a builder. In 1915, the time depicted in the statue, he was exploring the woodlands of the North Shore of the St. Lawrence, with an eye to sourcing pulp and paper for the hungry Tribune printing presses in Chicago. That is how, 22 years later, the company town of Baie Comeau came to be. Initially pulp and paper was the sole industry, but along the way Reynolds Aluminum established North America’s largest aluminum smelter, the deep water port attracted shipping and the town grew. It even produced Canada’s 18th prime minister.

There are two important rivers that empty into the St. Lawrence at Baie Comeau, the Outardes and the Manicouagan. Baie Comeau continued to prosper as Hydro Québec, over a 20-year period, beginning with the election of Jean Lesage in 1960, built the damns that harnessed the hydro-electric power potential of these magnificent rivers.

Dad didn’t say this was part of what we now know as the Quiet Revolution -- the Minister of Energy was Réne Lévesque -- but Hydro Québec were doers, creators and builders, and he knew the energy they were generating was not just hydro-electric.

§

The visionary Joseph R. Smallwood, Premier of Newfoundland, 1949 - 1972

Joey Smallwood styled himself as Canada’s “last father of Confederation”, having dragged Newfoundland, by dint of sheer will and oratory, kicking and screaming into Canada in 1949. That was only the beginning of his vision. He had much more in store.

Joey was determined to bring modern education standards to Newfoundland. A major objective was to elevate Memorial College to full university status. He achieved that soon after being elected Premier in 1949.

Joey’s first choice for University Chancellor was Max Aitken, better known as Lord Beaverbrook, the wealthy Canadian industrialist and newspaperman who memorably served as minister of nearly everything in Winston Churchill’s WWII war cabinet. Joey and Aitken had never met. In typical Smallwood fashion, Joey cold-called the Baron and wangled an introductory meeting. Beaverbrook graciously declined the Chancellorship, but the two hit it off personally and a relationship was formed.

In 1952, Joey was glad-handing and talking up a storm about his next great visionary project for his beloved Newfoundland and Labrador. He was determined to tap the province’s vast, but largely undeveloped, natural resources. The crowning glory would be harnessing the massive hydro-electricity generation potential of what was then known as Hamilton Falls on the Hamilton River in Labrador.

Much like King Charles granted Rupert’s Land to the Hudson’s Bay Company three centuries earlier, Joey was prepared to bestow a similar monopoly over an extraordinary swath of territory in Labrador to the right financial and operating partner. The search was on.

Joey was more inclined to look to the mother country than the US. He called up his pal Beaverbrook and said he was coming to London. Could Max possibly set him up for a meeting at Downing Street with Prime Minister Churchill? Beaverbrook and Churchill were no longer close. Max thought it highly unlikely that Winston would be inclined. Joey, pacing the floor at his rooms in the Savoy, would not be deterred. He pestered and pestered until miraculously an opening in the PM’s schedule was created.

The meeting took place late in the day over brandy and cigars, after Churchill returned from a wedding, at which presumably copious libations had already been consumed. The prospects for Smallwood making a memorable impression appeared remote. But Joey cranked it up and delivered a spell-binding sales pitch for his grand vision.

Afterwards Churchill said to an aide: “Ring up Tony [Anthony Rothschild] and tell him from me I would like him to see Mr. Smallwood.” Rothschild was the head of the British branch of the legendary family of bankers and financiers. A meeting was set up and once again Joey was masterful in his presentation. “It is probably the greatest storehouse of undeveloped natural wealth left in the world, and it’s ours,” he said. He pitched the development of Labrador as being “the beginning of England staging a great [post WWII] industrial comeback.”

Rothschild liked the story so much, in short order he brought in major partners and British Newfoundland Corporation (Brinco) came into being. It was granted exclusive mineral, timber and hydro-electric generation rights over territory larger than New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and PEI combined, for 99 years.

By 1972, Joey Smallwood’s impossible vision was realized. The Churchill Falls Generation Station (the falls and the river were renamed after Churchill died in 1965) was operational and inaugurated by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. It had been the largest construction project ever undertaken by a private company anywhere.

Trudeau congratulated “the dreamers as well as the workmen, the financiers as well as the engineers, the scientists as well as the managers” who made it happen. My father, was proud to have been one of them. And so am I.

Dad first regaled me with fantastical Joey Smallwood tales on that magical trip down the North Shore when I was 12. He made light of the last father of Confederation’s infamous failings and foibles, always drawing attention to what was best in Joey: the visionary doer, creator and builder.

§

YEAR-END REPORT CARD

Class of 2019: Another Index Beating Year

The Headmaster is well pleased with his visionary doers, creators and builders. Collectively, their class average (for the July 1 ‘18 to June 30 ‘19 school year) came in at a more than acceptable 10.3%. The comparable returns for the S&P 500, the Dow and the TSX, were respectively 8.2%. 9.6% and .6%.

“Never underestimate the importance of visionary leadership,” says the Headmaster, when assessing a potential investment. “Without the far-sightedness of founders and CEOs like Alain Bouchard at Alimentation Couche Tard, Bill Gates and now Satya Nadella at Microsoft, Steve Jobs and now Tim Cook at Apple, Darren Entwistle at Telus, Bruce Flatt and Sam Pollock at Brookfield, Bob Iger at Disney or Eric La Flèche at Metro -- I could go on -- the Class of 2020 would have very underwhelming prospects."

There were many outstanding performances in the Class over the past year, and few disappointments. Here are the sector by sector results.

Financials - B

TD Bank, Royal Bank, Bank of Nova Scotia and BlackRock continued their sojourn in the doldrums with an average return of -1.5%. “Keep the faith and enjoy those fat dividends,” advises the Headmaster. “This blue chip quartet continues to deliver consistent revenues, earnings and dividend growth, despite the naysayers. Their stock prices will catch up. It’s only a matter of time.” Promoted.

Resources - D

Sadly, the Headmaster concluded in May that he had no option other than to dispense with long-time class member Vermilion Energy. Despite positive cash flow and demonstrable balance sheet strength backing up a dividend that has never been cut dating back to the Crash of ‘08, the writing is on the wall: Vermilion, like its many Canadian peers, cannot win the respect of the market, no matter what it does. It’s performance to May was down 38.9% and falling.

The Headmaster is of the view that blame for the Canadian oil and gas sector’s woes cannot be laid entirely at the feet of government. Yes, things would be better for companies like Vermilion if one or two pipelines had been built by now. But in the larger scheme we have to ask ourselves: how close are we to the tipping point, when fossil fuels will start their slow inexorable descent? “That’s a wagon we do not want to be hitched to,” says the Headmaster, “especially against the backdrop of dramatically falling green energy prices.”

Nutrien, the fertilizer and agricultural retailing powerhouse, held up reasonably well, with a return of -2.1%. That negative statistic belies the reality of this class member’s admirable performance: despite one of the worst US planting seasons in years, the company still spun off cash. It is closing in on its target of $650 million in 2019 synergies from the merger of Agrium and Potash; it bought back $1 billion in shares in the second quarter; and still was able to hike its dividend. Promoted.

Utilities - B minus

Enbridge and newcomer Algonquin Power, who joined the class in May, produced a modest average return of .9%. Faced with permitting delays on new pipeline capacity, Enbridge performed remarkably well, managing to grow revenues, earnings and its dividend (now yielding an eye-popping 6%).

If fossil fuels are eventually heading to a tipping point, though, should one be hanging on to an aging oil and gas pipeline player like Enbridge? Says the Headmaster: “I ask myself the same question. As long as pipeline capacity is less than demand, it should bode well for Enbridge. It’s a seller’s market. I also like the fact that much of this class member’s revenue is tied to regulated long term rates. That’s a nice thing to have the next time we head into a downturn.” Promoted.

“Eventually, though, the green tide will turn, even against stalwarts like Enbridge. Which is why I asked Algonquin Power to join the class. The company is well managed and has an impressive and growing suite of renewable assets, including solar, wind, hydro-electric and geo-thermal. I think the tidal currents of change are at its back. To boot, it pays a decent 4.2% dividend.” Promoted.

Infrastructure - B plus

Brookfield Infrastructure, ably led by the visionary doer, creator and builder Sam Pollock, was up a tidy 11.3% at the end of the school year. The Headmaster particularly likes this class member because it affords him exposure to the kinds of long-lasting assets -- like toll roads, port terminals, transmission systems and cell phone towers -- that are often only available through private equity.

“I also like the fact that much of its income derives from fixed long-term contracts,” he adds. “This is the kind of company that can weather the storms.”

Brookfield has a growing dividend, currently yielding 4.2%. Promoted.

Retail - A

After resting on their laurels for the past year or more, both Alimentation Couche Tard and Metro showed us their true mettle over the past year with a sparkling average gain of 27.1%. Each uncorked double digit gains in revenues, earnings and dividend growth.

“Metro’s takeover of Jean Coutu is really starting to pay off,” says the Headmaster. “And Couche Tard is firing on all cylinders. The company is becoming a cash machine. It’s paying down debt ahead of schedule. We can expect another transformative acquisition in the coming months.” Promoted.

Industrials - B plus

CNR, John Deere and the packaging conglomerate CCL chalked up an average return of 10.2%. Despite international trade headwinds and market uncertainty, each managed to grow its revenues, profits and dividends in impressive style.

“I particularly commend Deere,” says the Headmaster. The American farmer has been hit by a double whammy of bad weather and ill-conceived trade policy. You’d think that the company might have suffered a retreat. But no, they reined in costs, while ramping up handsome gains from the recent acquistion of the Wirtgen heavy equipment group in Germany.” All promoted.

Healthcare - A

During the year Express Scripts was taken over by the managed care operator, Cigna. This resulted in a large gain. Averaged with class members Amgen and Johnson & Johnson, the collective performance was 19.4%.

“Of note,” says the Headmaster, “I decided in May to let Cigna go. We have done well with the takeover, but now Cigna is in a show-me mode as we wait to see it produce numbers to justify its expensive buyout of Express Scripts. I’m not comfortable with that.”

Both Amgen and JNJ cranked out workmanlike growth over the school year. Of late the market has tossed a wet blanket over JNJ, responding to its purported involvement in the opioid crisis. The company was fined a half a billion dollars by a judge in Oklahoma. Says the Headmaster: “Pharmaceutical companies are being sued all the time, and it is not unusual for unreasonably large amounts to be awarded in the lower courts. The appeals process takes years and almost inevitably results in dramatically reduced fines. If you don’t own JNJ, now is a good time to buy.”

Conversely, the market is delighted with Amgen’s recent announcement that it is going to purchase the blockbuster psoriasis drug Otezla from Celgene Corporation (which in turn is merging with Bristol-Myers Squibb). Both Amgen and Johnson & Johnson are promoted to the Class of 2020.

Telecom - B minus

“I continue to like Telus,” says the Headmaster. “And I like its visionary CEO Darren Entwistle.” When he joined Telus in 2000, the company was merely a regional landline operator. Entwistle engineered the takeover of the wireless player, Clearnet, that year for $6.6 billion. The stock tanked on the day the deal was announced. The market couldn’t see what Entwistle could see. Today Telus owns 30% of the Canadian national wireless market, and it contributes 50% of company profits. The stock price has marched upwards commensurately.

Telus was up 3.6% over the year. It has the lowest “churn rate” (turnover of customers) in the industry. The dividend is yielding 4.6% and the company is growing it at 7 per cent per annum. Promoted.

Information Technology - A plus

This group includes Microsoft, Open Text, Apple and Visa. Collectively and individually they had a great year, with an average return of 22.6% and financial performance to match. The only cloud in the sky was a drop in sales and expectations for Apple, courtesy of President Trump’s trade war with China. Even so, the company managed a respectable return of 6.9% and continues to gush free cash, much of which it is returning to shareholders via buybacks.

All promoted.

Entertainment - A plus

Bob Iger and Disney came into their own this year and the Headmaster is delighted. The stock was up a scintillating 33.2%. The catalyst, as predicted in this publication, was the market’s long delayed recognition that Disney is going to be a force to contend with in the delivery of direct-to-consumer streamed content. Under CEO Iger’s visionary leadership, the company is soon to launch streamed bundles to include Hulu, offerings from the Fox and Disney film and television libraries, and ESPN. Says the Headmaster: “Netflix can’t come close to matching this.” The market seems to agree. Promoted.

If you would like further information on any of the investing ideas raised in this issue, or a complimentary consultation, please call or email.

CW

0 notes

Text

Jim Lehrer, Longtime PBS News Anchor, Is Dead at 85

Jim Lehrer, the retired PBS anchorman who for 36 years gave public television viewers a substantive alternative to network evening news programs with in-depth reporting, interviews and analysis of world and national affairs, died on Thursday at his home in Washington. He was 85.

PBS announced his death.

While best known for his anchor work, which he shared for two decades with his colleague Robert MacNeil, Mr. Lehrer moderated a dozen presidential debates and was the author of more than a score of novels, which often drew on his reporting experiences. He also wrote four plays and three memoirs.

A low-key, courtly Texan who worked on Dallas newspapers in the 1960s and began his PBS career in the 1970s, Mr. Lehrer saw himself as “a print/word person at heart” and his program as a kind of newspaper for television, with high regard for balanced and objective reporting. He was an oasis of civility in a news media that thrived on excited headlines, gotcha questions and noisy confrontations.

“I have an old-fashioned view that news is not a commodity,” Mr. Lehrer told The American Journalism Review in 2001. “News is information that’s required in a democratic society, and Thomas Jefferson said a democracy is dependent on an informed citizenry. That sounds corny, but I don’t care whether it sounds corny or not. It’s the truth.”

Mr. Lehrer co-anchored a single-topic, half-hour PBS news program with Mr. MacNeil from its inception in 1975 to 1983, when it was expanded into the multitopic “MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour.” It ran until Mr. MacNeil retired in 1995. The renamed “NewsHour With Jim Lehrer” continued until 2009, when he reduced his appearances to two and then to one a week until his own retirement in 2011.

Critics called Mr. Lehrer’s reporting, and his collaborations with Mr. MacNeil, solid journalism, committed to fair, unbiased and far more detailed reporting than the CBS, NBC or ABC nightly news programs. To put news in perspective, the two anchors interviewed world and national leaders, and experts on politics, law, business, arts and sciences, and other fields.

It was not unusual to see presidents, prime ministers, congressional and corporate leaders and other luminaries interviewed on “MacNeil/Lehrer.” Early subjects included the Shah of Iran, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and Presidents Anwar Sadat of Egypt and Fidel Castro of Cuba. Mr. Lehrer also interviewed nearly all of America’s presidential and vice-presidential candidates from 1976 on.

With Mr. Lehrer reporting from Washington and Mr. MacNeil from New York, the program sought to represent all sides of a controversy by eliciting comments from rivals for public attention. But the anchors deliberately drew no sweeping conclusions of their own about disputed matters, allowing viewers to decide for themselves what to believe.

The approach had its drawbacks. An extended presentation of authoritative voices offering conflicting viewpoints left some viewers dissatisfied, if not confused. Many found the technique elitist and dull, and even some critics called it boring — or, worse, a willful refusal by Mr. Lehrer and Mr. MacNeil to make hard judgments about adversarial issues affecting the public interest.

In The Columbia Journalism Review in 1979, Andrew Kopkind wrote: “The structure of any MacNeil/Lehrer Report is composed of talking heads rather than explosive images, of conversation covering several points of view rather than a homogeneous statement of the world’s condition, of panels of experts, proposals for policy, and the sense of incompleteness — and therefore of possibility — rather than a feeling of finality.”

Edwin Diamond, writing in The New York Times that year, said the hosts had “gradually created one of the best half-hours of news on television without ‘visuals’ at all; the major elements of the program are the interviewers themselves, always prepared with good questions, and the quality of their guests, always specialists on the night’s single topic and almost always capable of speaking fresh, intelligent thoughts.”

“MacNeil/Lehrer” audiences were small compared to the network news shows, which drew far more viewers with videotaped coverage and news summaries that critics called headlines for people who did not read daily newspapers. But surveys found that PBS viewers were better educated, and that they were newspaper readers who tuned in to amplify what they knew.

Mr. Lehrer and Mr. MacNeil each declined lucrative job offers from television networks. Unlike commercial networks, “MacNeil/Lehrer” relied on donations by corporations, foundations and wealthy individuals; by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, a nonprofit creation of Congress; and by MacNeil/Lehrer Productions, created in 1981 to support their franchise, specials and documentaries.

In 1986, Mr. Lehrer hosted the documentary “My Heart, Your Heart,” which was based on his experience of double-bypass surgery and recovery in 1983. The program, on PBS, won an Emmy and an award from the American Heart Association. He also hosted “The Heart of the Dragon,” a 12-part series on modern China, also shown in 1986.

Known mainly to PBS viewers, Mr. Lehrer became one of television’s most familiar faces by moderating presidential debates, starting in 1988 with the first between Vice President George H.W. Bush and Gov. Michael S. Dukakis of Massachusetts, and continuing in every presidential campaign through 2012, sometimes including two or three debates in a year.

Complaints by candidates and pundits about moderators’ performances became a tradition of election seasons, and Mr. Lehrer, often called the “Dean of Moderators” for his many appearances, was singled out repeatedly, accused of being too easygoing or too strict in enforcing the rules, of being too soft or too hard on the debaters.

In 1988, when critics said he was not aggressive enough with the candidates, Mr. Lehrer snapped, “If somebody wants to be entertained, they ought to go to the circus.” In 2008, he was said to be too aggressive in trying to get Senator John McCain of Arizona and Senator Barack Obama of Illinois to engage with each other.

In the 2012 debate, it was Mr. Lehrer’s light touch that came under fire. President Obama and former Gov. Mitt Romney of Massachusetts at times ignored Mr. Lehrer, who strained to interrupt when they exceeded their allotted speaking times, and rules were violated repeatedly. Both campaigns accused Mr. Lehrer of losing control of the debate.

The Commission on Presidential Debates defended Mr. Lehrer, saying it was his job to get the candidates talking, not to insert himself into their dialogue. For his part, Mr. Lehrer said his task had been “to facilitate direct, extended exchanges between the candidates about issues of substance” and “to stay out of the way of the flow,” adding, “I had no problems with doing so.”

James Charles Lehrer was born in Wichita, Kan., on May 19, 1934, to Harry Lehrer, who ran a small bus line and was a bus station manager, and Lois (Chapman) Lehrer, a teacher. Jim attended schools in Wichita and Beaumont, Tex., and graduated from Thomas Jefferson High School in San Antonio, where he edited a student newspaper.

He earned an associate degree from Victoria College in Texas in 1954 and a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Missouri in 1956. Like his father and his older brother Fred, he joined the Marine Corps. He was an infantry officer on Okinawa, edited a camp newspaper at the Parris Island Marine training center in South Carolina and was discharged as a captain in 1959.

In 1960, he married Kate Staples, a novelist. She survives him, along with three daughters, Jamie, Lucy and Amanda, and six grandchildren.

From 1959 to 1961, Mr. Lehrer was a reporter for The Dallas Morning News, but he quit after the paper declined to publish his articles on right-wing activities in a civil defense organization. He joined the rival Dallas Times Herald, where over nine years he was a reporter, columnist and city editor.

He also began writing fiction. His first novel, “Viva Max!” (1966), about a Mexican general who triggers an international incident by trying to recapture the Alamo, was made into a film comedy starring Peter Ustinov and Jonathan Winters.

In 1970, Mr. Lehrer joined KERA-TV, the Dallas public broadcasting station, where he delivered a nightly newscast. In 1972, he became PBS’s coordinator of public affairs programming in Washington. He quit over funding cuts, but in 1973 he joined WETA-TV in Washington, became a PBS correspondent and met Mr. MacNeil, a Canadian who had reported for NBC-TV and the BBC.

They co-anchored PBS telecasts of the Senate Watergate hearings, investigating the break-in by Republican operatives at the Democratic National Committee headquarters, an episode that set off a political dirty-tricks scandal that led to the downfall of Richard M. Nixon’s presidency. The telecasts began the partnership that would carry the two broadcasters to television fame.

Mr. Lehrer won numerous Emmys, a George Foster Peabody Award and a National Humanities Medal. He and Mr. MacNeil were inducted into the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences Hall of Fame in 1999.

He lived in Washington and had a farm in West Virginia, where he kept a 1946 Flxible Clipper bus, the centerpiece of his collection of bus memorabilia.

Mr. Lehrer’s memoirs were “We Were Dreamers” (1975), “A Bus of My Own” (1992) and “Tension City: Inside the Presidential Debates” (2011). His plays were “Chili Queen” (1986), a farce about a media circus at a hostage situation; “Church Key Charlie Blue” (1988), a dark comedy on a bar flare-up over a televised football game; “The Will and Bart Show” (1992), about two cabinet officials who loathe each other; and “Bell” (2013), a one-man show about Alexander Graham Bell.

Writing nights and weekends, on trains, planes and sometimes in the office, Mr. Lehrer churned out a novel almost every year for more than two decades: spy thrillers, political satires, murder mysteries and series featuring One-Eyed Mack, a lieutenant governor of Oklahoma, and Charlie Henderson, a C.I.A. agent. “Top Down” (2013) revolved around the 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy, which Mr. Lehrer had covered as a young reporter in Dallas. Critics called his fiction workmanlike, relying more on twisty plots than characters and dialogue.

“His apprenticeship came at a time when every reporter, it seemed, had an unfinished novel in his desk — but Lehrer actually finished his,” Texas Monthly said in a 1995 profile.

But it was as a newsman that Mr. Lehrer was best remembered.

“Jim Lehrer is no showboat,” Walter Goodman wrote in The Times in 1996. “That is a considerable distinction for television, where the interrogators are often bigger than their guests or victims. This man of modest mien keeps the spotlight on the person being questioned. His somewhat halting conversational manner invites rather than commands. And his professional principles dispel any fears that he is out to get not just his guests’ point of view but also the guests themselves.”

from WordPress https://mastcomm.com/business/jim-lehrer-longtime-pbs-news-anchor-is-dead-at-85/

0 notes