#isin-larsa period

Text

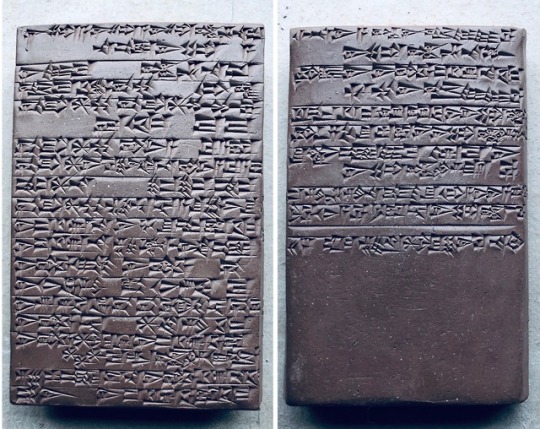

Sumerian cuneiform tablet (clay, c. 1808 BC)

This tablet dating from the Old Babylonian Period is an administrative record of the distribution of three male sheep for various purposes in the palace. The issuance describes one for a ceremonial meal, one for the throne room and one for the women's quarters. The tablet is dated to the fourteenth year of the reign of Rim-Sin I of Larsa and records the year as when the troops of Uruk, Isin, Sutium and Rapiqum were destroyed, and Irdanene, king of Uruk, was struck with a weapon.

image and text from here

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

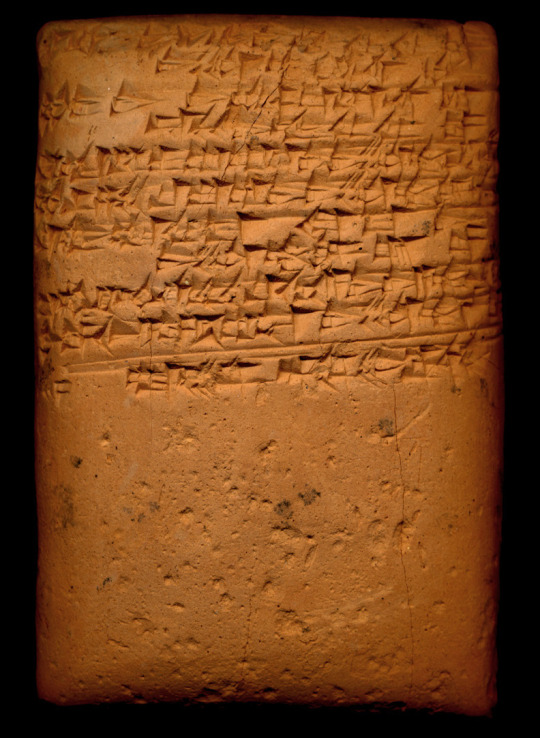

The Behistun Inscription and the Anubanini Relief

The Anubanini rock relief, also known as the Sar-e Pol-e Zahab rock relief, is a significant archaeological artifact located in western Iran, near the town of Sarpol-e Zahab in Kermanshah Province.

The rock relief is believed to date back to either the Akkadian Empire period (circa 2300 BC) or the Isin-Larsa period (early second millennium BC).

The relief is thought to belong to the Lullubi culture, which was one of the ancient cultures in the Zagros Mountains region.

The relief shows a scene of several defeated rulers falling at the feet of the Anubis, accompanied by the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar.

Anubanini and the defeated ruler. He is equipped with an axe, a bow and an arrow. He is bare-chested, wears a short skirt, a roll-brimmed hat and sandals.

Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar. She wears a long, flounced dress, a hat decorated with horns and a headed collar. She is extending a ring in her right hand and has club-like weapons in her back.

Prisoners and their king (detail).

There's also an inscription in the Akkadian language and Akkadian script. In the inscription, he declares himself as the mighty king of Lullubium, who had set up his image as well as that of Ishtar on mount Batir, and calls on various deities to preserve his monument.

Anubanini, the mighty king, king of Lullubum, erected a image of himself and an image of Goddess Ninni on the mount of Batir... (follows a lengthy curse formula invoking deities Anu, Antum, Enlil, Ninlil, Adad, Ishtar, Sin and Shamash towards anyone who would damage the monument).

Behistun reliefs

This rock relief is very similar to the much later Achaemenid Behistun reliefs (fifth century BC), not located very far, to such an extent that it was said that the Behistun Inscription was influenced by it. The attitude of the ruler, the trampling of an enemy, the presence of a divinity, the lines of prisoners are all very similar.

Source: Wikipedia

#ancient mesopotamia#mesopotamia#archaeology#ancient history#ancient iran#achaemenid#anubanini#anubanini relief

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

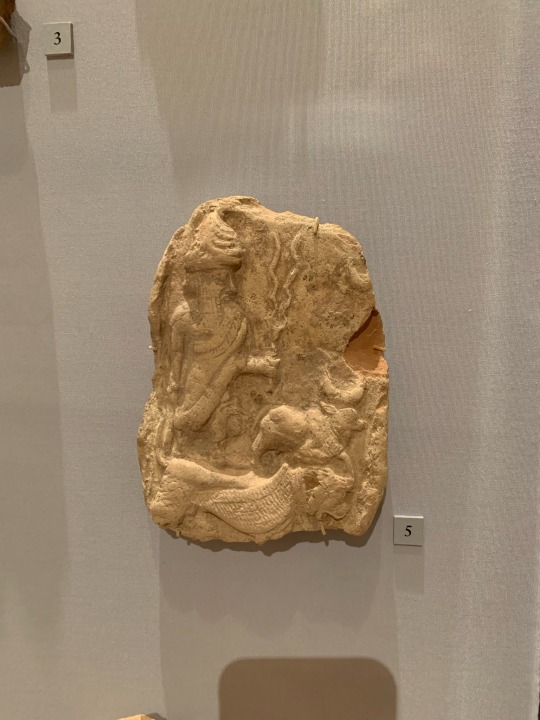

Terracotta plaque depicting an enthroned goddess

Diqdiqqah, a suburb of Ur (Tell al-Muqayyar), Iraq

Isin-Larsa or Old Babylonian period, ca. 2000-1600 BCE

Penn Museum, Philadelphia, PA

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ea-Nasir, the merchant famous for his bad copper

A bad reputation is eventually forgotten and, if your memory is inconvenient, a damnatio memoriae eliminates even your good reputation. Despite this, there are people whose bad opinion endures for centuries or even millennia. As many others as there may be, Ea-Nāṣir is the paradigm of disrepute.

Its history is set in the Isin-Larsa period, in the city of Ur at the time of Larsa's splendor, during the reign of Rim Sin I, before Hammurabi of Babylon united the whole region, and when it was the nerve center of the Persian Gulf trade. Then, in the temple of Šamaš, traders met with investors. Investors paid in silver or other trade goods, mainly reed baskets, but also objects such as bracelets. Ea-Nāṣir was a merchant who mostly brought copper from Dilmún, as well as precious stones and spices. The territory of Dilmun corresponded to Bahrain and Failaka Island (Kuwait). Each investor only risked his share and, if all went well, he could take a share of the profits. Although Ea-Nāṣir took most of the profits, since each investor was only responsible for his share, the additional costs were borne by him. Thus, by taking less risk, the door was open to the small investor, who also did not need to bring in great wealth, although the profits depended on what could be obtained by trading what was offered.

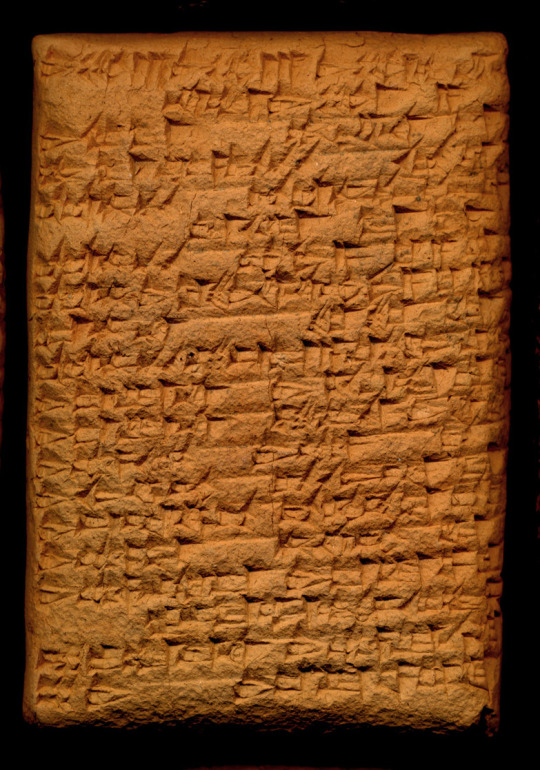

Ea-nāṣir’s tablets

Unfortunately, whether by sea or land, trade is risky and merchandise is often lost. There were also dishonest traders and dissatisfied investors. At No. 1 Old Street in Ur, Sir Leonard Wooley found, between 1922 and 1934, 29 tablets from the so-called Ea-Nāṣir archive. This one we know mainly from a tablet where Nanni presents a complaint (UET V 81). This is the oldest known complaint:

Tell Ea-Nāṣir: Nanni sends the following message.

When you came, you told me in such a way "I will give Gimil-Sin (when he arrives) copper ingots of good quality." You left but did not do what you promised me. You showed ingots that were not good before my messenger (Ṣīt-Sin) and said "If you want to take them, take them, if you do not want them, go!"

Why do you take me, that you treat someone like me with such contempt? I have sent as messengers gentlemen like us to collect the sack with the money (deposited with you) but you have treated me with disdain by sending them to me several times empty-handed, and that for enemy territory. Is there anyone among the merchants of Dilmun who has treated me in such a manner? Only you treat my messenger with contempt! Regarding that (insignificant) mine [~0.5-1 kg] of silver I owe you, feel free to speak in such a manner, while I have given the palace on your behalf 1 080 pounds of copper, and Šumi-abum has also given 1 080 pounds of copper, in addition to what we have both had written on a sealed tablet to keep in the temple of Šamaš.

How have you treated me for that copper? You have withheld my bag of money from me in enemy territory; now it is up to you to restore me (my money) in full.

Know that (henceforth) I will not accept here any copper from you that is not of good quality. I shall (henceforth) select and take the ingots individually from my own yard, and I shall exercise against you my right of refusal because you have treated me with contempt.

Both are mentioned again in another tablet (UET V 66):

Talk( to Ea-Nāṣir)

and, thus says Nanni.

May Šamaš bless your lives. Since you wrote to me, I have sent Igmil-Sin to your [...]. The copper from my purse and the purse of Eribam-Sin, seal it for him. He can bring it. Give good copper to him.

We may note that Ea-Nāṣir must have been in trouble regularly, for he needed to appease two men (UET V 72):

Tell the Shumun-libshi and the Zabardabbû [Sumerian loan: coppersmith or one who stored copper]:

Ea-Nāṣir and Ilushu-illasu say:

Concerning the situation with Mr. "Shorty" [kurûm] and Erissum-matim, who came here, do not be afraid.

I made them enter the temple of Šamaš and take an oath. They said, "We did not come for those matters; we came for our business."

I told them, "I will write to you" - but they did not believe me!

He said, "I have a dispute with Mr. Shumun-libshi." He said, "[...] to your partner. I took, and you did not do [...]. You did not give it to me."

In three days, I will reach the city of Larsa.

Also, I spoke to Erissum-matim and said, "What is your sign [password, hidden omen, personality]?"

I said to the teapot maker, "Go with Ilum-gamil to the Zabardabbû, and take the deficit for me, and put it in the city of Enimma."

Also, do not neglect your [...].

Also, I have given the ingots of which we spoke to men.

[Written on the edge] Don't be critical! Take the [...] from them! Don't worry! We'll come and get you.

The tension could turn to jest (UET V 20):

Speak to Ea-Nāṣir; thus says Ili-idinnam. Now, you have done a good job! [with sarcasm]. A year ago, I paid silver. In a foreign country, (only) you will retain bad copper. If you wish, bring your copper.

For, apparently, the precious copper did not always reach the one who wanted it (UET V 29):

Speak to Ea-Nāṣir; thus says Muhaddum concerning the ingots: the sealed tablet of your companions has "gone" with you. Now Saniqum and Ubajatum have gone to see you. If you really are my brother, send someone with them, and give them the ingots that are at your disposal.

So he had to worry about keeping the investors in a good mood (UET V 22):

Speak to Ea-Nāṣir, thus says Ilsu-ellatsu regarding the copper of Idin-Sin, Izija will come to you. Show her 15 ingots so that she can select 6 good ingots and give those to them. Act so that Idin-Sin does not get angry. To Ilsu-rabi give 1 copper talent from Sin-remeni, the son of [...].

On the whole, whether by his failures or his successes (UET V 5), it is shown that Ea-Nāṣir's main activity was to bring copper in exchange for silver:

Speak to Ea-Nāṣir; thus Appa says.

My copper give it to Nigga-Nanna - good (copper) - so that my heart will not be tormented;

Besides copper from 2 silver mines Ilsu-ellatsu asked me to give.

[...]

With my copper, for 1(?) silver mine give copper and silver (for him). I will pay [...]. And a copper kettle

that (may) contain 15 qa [qa≈10 cm3] of water and 10 mines of other copper send it to me. I will pay silver for it.

Some of the people are recurrent, such as Sumi-abum (UET V 55):

Speak to Ea-Nāṣir and Ilsu-ellatsu; thus says Sumi-abum. May Samas bless your lives.

Now summatum and [...] to you I have sent. They have come to you. 1 silver mine he (they or I) has (have/have) sent.

The state of preservation of the tablets sometimes leaves us with questions, such as what question there was regarding the apprentice (UET V 54).

Speak to Ea-Nāṣir; thus says Sumi-abum. Concerning the question [...] of the apprentice [...].

Finally, tablet records what looks like an inventory (UET V 848/BM 131428):

11 garments:

1/3 mine value [mina≈0.5-1 kg], 2 2/3 shekels of silver [shekel≈8.3 g].

5 garments:

value: 13 silver shekels.

2 garments

value: 6 1/2 silver shekels

5 garments: value: 10 2/3 silver shekels

27 garments:

value: 5/6 mina, 4 1/2 shekels, 15 še [še≈0.05 g].

-------

(total) 50 garments:

value: 1 2/3 mina, 7 1/3 shekels, 15 še:

in the hands of Mr. Ea-Nāṣir.

Šamaš’s temple

It is convenient to remember that Šamaš was the solar god, who dispensed justice because he could see from the sky. His temple was a place for agreements, distributing fairly, with the god as witness, profits and losses. As they had a good reputation, the temples were a place to deposit money, serving as a bank and offering loans. The divine awe ensured that borrowers would repay and kept interest rates low. These temples also stored private goods marked with their corresponding seals to distinguish their owners. In addition, although citizens did not own the temples, they owned land on behalf of the former. These were regional economic engines that the state kept in check with taxes to prevent them from accumulating too much power, but without harming local productivity.

Copper trade

During the Bronze Age, copper was incredibly important in Mesopotamia for its practical and military applications. In the Akkadian Empire (c. 2334-2154 B.C.) and the third dynasty of Ur (c. 2112-2004 B.C.), Mesopotamian temples organized trips to Magan, on the Oman peninsula, and Meluhha, in the Indus Valley. Magan then had a monopoly on copper, but in the Isin-Larsa period (2025-1763 B.C.), this responsibility rested in the hands of the traders themselves. However, their efficiency must have been good enough for the state not to take control of the trade and entrust them with the palace's copper supply. It was then that Dilmun began to prosper to the detriment of Magan, which temporarily coincided with the decline of the Indus Valley civilization. This copper would have come to Dilmun from Gujarat, Rajasthan, in present-day India, and the southern half of Iran. However, this prosperity would gradually disappear from the end of the Isin-Larsa period. With the decline of the successive Paleo-Babylonian Empire (1792-1595 B.C.) and the rise of the later Kassite Empire (c. 1531-1155 B.C.), Mesopotamia obtained copper from Cyprus, so that the Dilmun copper merchants went bankrupt.

In its period of prosperity, the price of copper in Dilmun must have been attractive to Persian Gulf traders, who transported it in large quantities. The palace of Larsa was a participant in this trade and was possibly the main investor in Ea-Nāṣir, for he imported as much as 18 tons for it. Some of the names mentioned on the tablets could belong to palace administrators.

Usually, Ea-Nāṣir traveled by sea to Dilmun to buy copper in exchange for silver, staying there for a while, at which time he sent the ships to Ur. Tablets with orders and reproaches would reach him while there and he would subsequently take them to his house in Ur. In this, he had a large courtyard and furnaces with models and tools, so perhaps copper was worked there and some customers brought copper to obtain a specific product, such as teapots. This occupation would increase the fire risk of the domicile, explaining the state of some of the slats. Since he had a large business with the palace, perhaps that is why he could afford to neglect minor investors. While in Dilmun, some of his investors gave copper to the palace on his behalf. Of the recurring names, Nanni would have been a local copper merchant, while Arbituram a creditor to whom Ea-Nāṣir owed debts. Nigga-Nanna was possibly a middleman employed by Ea-Nāṣir.

0 notes

Note

Hey yama, I wanted to ask what you think are the biggest examples of misinformation OSP has spread in their myth videos?

Well, the Ishtar section of the underworld myths vid comes to mind, it's a nightmare:

1. calls Ishtar's Descent "four thousand years old" and "Babylonian." It's probably around 3000 years old, and soundly Assyrian, with no copies known from Babylonia. Now, Inanna's Descent - that one IS around 4000 years old and Babylonian (oldest copies come from the Isin-Larsa period).

2. claims Epic of Gilgamesh forms a "backstory" of this myth which applies a very modern popcultural notion of continuity (and it doesn't even work well tbh since Epic of Gilgamesh pretty clearly presents Tammuz as already dead)

3. i would personally not call a derivative of technically genderless beings made out fingernail dirt from the Sumerian original " lgbt representation"; that is not the term used in the vid but i do not like to use a certain word which starts with q because it's closest equivalent in my native language has... incredibly unsavory implications i'd rather not discuss. This is not the fault of the vid itself but it also created the false notion common online (relatively speaking) that Ahushunamir was "the frist nonbinary person" on record or whatever which, putting aside what I said above, strikes me as dubious because you have the likes of Shaushka and Ninsianna, who by modern standards imo count as genderfluid, in Ur III period records already, and also have the bonus of being major, popular deities and not Fingernail Dirt Expandable Artificial Beings (note we sadly cannot really extrapolate this into assuming acceptance for similar gender expression in everyday life, otherwise we'd have to assume most women in ancient Mesopotamia were literate, since most goddesses are described as literate)

The Aphrodite vid is also bad:

1. "Astarte is also Ishtar" is simply not true. Ashtart is attested in Mari independently from Ishtar in Akkad in the 3rd millennium BCE (I think I got a confirmation from W. G. Lambert's old review of Penglasse's book?). The names are cognate, sure, but this is like saying "Zeus is Tyr" ultimately.

2. Lies about the Kumarbi myth in many, many ways at once:

a) Kumarbi is HURRIAN, not Hittite. The myth was TRANSLATED into Hittite but so was Gilgamesh and a story about El and Athirat, does not make them "Hittite" myths in origin.

b) the myth is not about "birth of Ishtar," it's about the birth of Teshub. Now, Hurrian Shaushka IS the sister of Teshub, and Song of Silver does imply her (or their, since Shaushka proudly shows up both among gods and goddesses on the Yazilikaya reliefs and, as remarked by Hurrian texts themselves, possessed "male attributes" and "female attributes" at once, despite usually being referred to as a goddess) father is also Kumarbi, but we have no account of her birth. Shaushka was regarded as analogous to Ishtar - "Ishtar of Nineveh" or "Ishtar of Subartu" - but so were other goddesses. Does not make them the same as Ishtar. While the gender non-conforming ventures and interest in love and war are shared between both, Shaushka lacks Ishtar's astral aspect but has a healing role which Ishtar lacks, for instance.

I remember seeing people point out the Dionysus takes in their vids are... quite something so that surely qualifies too.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Priests & Priestesses" from Gods, Demons, & Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia by Jeremy Black

In almost the earliest written documents are found lists of the titles of officials, including various classes of priest. Some of these are administrative functionaries of the temple bureaucracy and others are religious specialists dealing with particular areas of the cult.

Later records make it clear that a comples hierarchy of clergy was attached to temples, ranging from 'high priests' or 'high priestesses down to courtyard sweepers. It is not clear whether there were fixed distinctions between sacerdotal clergy and administrative clergy: one particular type of priests is called 'anointed'; others are 'enterers of the temple'. suggesting that certain areas of the shrines were restricted of access.

Generally speaking female clergy were more common in the service of female deities, but a notable exception was the e (Akkadian entu), the chaste high priestess in the temples of some gods in the Sumerian and Old Babylonian Periods, notably that of the moon god Nanna-Suen at Ur where the office was revived by Nabonidus in neo-Babylonian times - and in temples at Larsa, Isin, Sippar, Nippur and Kiš. Sometimes the office was held by a daughter of the king. Other priestesses were:

*the parentheses indicate the Akkadian translation of the Sumerian*

naditu, ugbabtu: these lived secluded lives in a residence within the temple, although they could own property and engage in business.

qadištu, kulmasītu: these, in contrast, may have been involved in ritual prostitution.

Among the classes of priests were:

en (Akkadian ēnu): a priest corresponding to the entu, but serving in the cult of female deities such as Inana of Uruk

mašmas (ašipu or mašmaššu): magiciaus specialising in medical and magicd sites to easure protection from demons, disease and servery

mas-su-gid-gid (bārú): diviners specialising in extispicy

gala (kalû): musicians specialising in performance of balag and other cult songs, probably in choirs, accompanied by drums.

nar (nāru): musicians specialising in solo performance of praise songs, accompanying themselves on stringed instruments; in general, singers.

muhaldim (nuhatimmu): temple cooks; there were also slaughterers, brewers, etc.

išib (pašīšu and ramku): priests specialising in purification rituals.

sanga (sangủ): generally “priests’, but also administrators;

šatam (šatammu): temple administrators; (female) (male sale, female si la dream interpreters.

Priests and priestesses may have entered the clergy through dedication. They were probably distinguished by their priestly dress, especially by their hats or (in some cases) by being shaven-headed, or by their nudity. The titles and functions of the priests varied, of course, from time to time and place to place.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Adornment of a Goddess with Scents: A Sumerian shirnamshuba song of the Goddess Ninisina

This is my rendition of a cultic song of Ninisina, the chief deity of the important Mesopotamian city of Isin, whose most prominent role in the larger Mesopotamian pantheon was that of a healing goddess, a role she shared with a number of other goddesses such as Gula, Nintinuga, and Bau. Her son Damu, a so-called “dying god” who was widely featured in Sumerian lamentations and was associated in this role with Dumuzi, frequently assists her in her curative procedures. A remarkable Sumerian letter of the Larsa king Sin-iddinam to Ninisina herself (one of a number examples of letters of humans to gods) survives to us where Sin-iddinam implores the goddess to cure a grave illness that cannot be diagnosed that a demon infected him with in a dream. She is also memorably depicted as a ferocious protector of king Shulgi’s enemies in a shirnamerima song, the so-called “Execration of Shulgi’s Enemies” or “Shulgi S,” where in one passage, she seems to use her knowledge as a physician to maximize harm to the enemy. Ninisina’s spouse was the warrior god Pabilsang, chief god of the city of Larak, one of the five original cities of Mesopotamia before the gods sent the great flood. Pabilsang is best known to posterity for his place in the nighttime sky as the constellation Sagittarius.

In this text, Ninisina is described as adorning her body with various oils and perfumes. In ancient Mesopotamia, the perfume industry was relatively advanced and utilized a number of aromatic trees and plants, many of which were exotic imports. Most famous was the eren tree, originally understood to grow in the eastern mountains, which was the prize sought by Gilgamesh in his heroic journey, leading to conflict with Huwawa, the guardian of the forest, who was imbued with paralyzing aurae. The song does not mention it explicitly, but the goddess was most likely applying scents over the whole of her naked body while beautifying herself for sex with her spouse (or possibly the mortal king, although there is more evidence for this practice with the goddess Inana). The application of perfumes is featured during the most detailed account of the so-called “sacred marriage ritual” between king Iddin-Dagan of Isin and the goddess Inana.

The lone ancient manuscript of this text currently known to us is an immaculately preserved manuscript in the Harvard Semitic Museum. Here is a picture (credit Havard Semitic Museum and the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative):

The text was first published in copy in the Journal of Cuneiform Studies in 1962. The original editor of this text, Mark Cohen (“The Incantation-Hymn: Incantation or Hymn?,” Journal of the American Oriental Society volume 95 (1975), pg. 601, see also the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk), text number 4.22.2) suggested that this cultic song may have been performed while the statue of the goddess was naked in order to appease her anger.

The reading of this text in the original Sumerian and its translation is as follows. The character “š” is pronounced “sh” and the character “ĝ” is pronounced “ng” (a nasal “n”). The subscripted numbers are not pronounced, and the signs given in brackets ({...}) are not pronounced (they merely indicate what category the word belongs to). My translation differs substantially from the previous edition of this text (including several different sign readings and values). A backslash indicates where the line has been indented.

1. i3-li-a i3-li-a i3-li he2-en-na-tum2 /na-aĝ2-i3-li-a

2. i3 lum-ma he2-en-na-tum2

3. tum-ma sag9-ga-ĝu10 ul-la

4. ga-ša-an-ĝu10 ga-ša-an sir2-sir2-e /ama ugu ma-ma

5. ga-ša-an-ĝu10 kurun-a tuš-a-ra

6. Ga-ša-an-i3-si-in{ki}-na kurun-a tuš-a-ra

7. izi an-na mu2-mu2-de3

8. ga-ša-an-ĝu10 sim{mušen} -gin7 tu5-tu5-a

9. i3 {ĝeš}eren-na i3 ha-šu-ur2-ra-ka

10. i3 {ĝeš}eren-na nam-dim3-me-er ki aĝ2

11. i3 šim-gig i3 bulugx-ga

12. i3 ab2 kug-ge gara2 ab2-šilam-ma

13. i3-nun tur3 kug ga-ga amaš-gin7 ga-ga

14. i3 šim-gin7 an-šag4-ge-ka

15. i3 ligidba(ŠIM.{d}NIN.URTA) {ĝeš}eren babbar-ra-ka /mul-ma-al he2-em-mi-ib2-za

16. zi-pa-aĝ2-ĝa2-na i3 šim {ĝeš}eren-na-ka

17. gaba-ni i3 {ĝeš}eren babbar-ra-ka

(reverse)

18. igi-na i3-a he2-ni-ib2-lum-lum-e /i3-li he2-en-na-su3

19. gu-sa-ni i3 šim {ĝeš}eren-na-ka /hu-mu-ni-ib2-lum-lum-e

20. siki ur2 siki pa dub-dub-ba-ni i3-li he2-en-na-an-su3

21. gu2 bar za-gin3 šu gur-ra-ni i3-li he2-em-su3-su3

22. šu ĝir3 aĝ2-lum-ma-lam-ma-ni /i3-li he2-em-luh-e

23. ĝeš-ge-en-ge-na alan šu du7-a i3-a he2-en-nu2

24. nin ab2 a-e ĝar-ra-gin7 i3 he2-la2-e

(double ruling)

25. 24 šir3-nam-šub {d}Nin-isin2{si}-na-kam

<br />

1. Fine oil shall be fitting for her, it is the “state of (being covered in) fine oil”!<br />

2. Luxuriant oil shall be fitting for her!

3. My beautiful …, swollen (with attractiveness),

4. My lady, Lady Sirsir, birth mother …,

5. For my lady, who dwells among the liquor,

6. For Ninisina, who dwells among the liquor,

7. Fire is burning in the sky!

8. My lady, bathing like a swallow

9. Oil of juniper, oil of cypress

10. Oil of juniper, loved by divinity

11. Oil of the shimgig tree, oil of the bulug tree

12. Butter of the pure cow, cream of the cow

13. Ghee of the pure cattle pen, cream(?) as if (from) the sheepfold, cream

14. Like oil resin, it is of the midst of heaven

15. Oil of the euphorbia plant, oil of white juniper, may it splash (upon you)

16. On her throat, oil of juniper

17. On her chest, oil of white juniper

18. On her face may oil be made luxuriant! May fine oil be sprinkled upon her!

19. On the muscles of her neck, may oil of juniper be made luxuriant!

20. On her hair, styled from base to tip, may fine oil be sprinkled upon her!

21. On the nape of her neck, ringed with lapis, may fine oil be sprinkled upon her!

22. May fine oil cleanse her hands and feet, that which flourish and thrive(?)

23. May her perfect limbs and form lie in oil!

24. May the woman, like a cow placed in the water, be immersed in oil!

subscript: 24 lines: it is a shirnamshub song of Ninisina.

line 1) The very beginning of the song is pronounced “ili’a ili’a ili.” Such a replication of the “l” noise, called “ululation,” is frequently employed at the beginning of Sumerian cultic songs.

line 3) “tum” is primarily a value used to spell Akkadian words, the meaning of Sumerian tum here is obscure. The spelling tum-ma is possibly an error for ib2-ba “hips,” which in this context would have a highly sexualized connotation, in the possession of the would-be lover.

line 4) Possibly reflecting the Etarsirsir temple in the city of Girsu, which was a temple of the goddess Bau, who is associated with Ninisina as a healing goddess during this period. ma-ma possibly reflects the Emesal form of the verb ĝar “to set, put, establish” or the divine name Mama. Mama was a birth goddess: if correct, the reference here is unclear, but may have a sexual connotation.

line 5) Presumably this describes the goddess’s participation in a banquet.

line 9) Sumerian eren is often translated as “cedar” based on the association of the tree with the Lebanese cedar arising primarily from the Akkadian Gilgamesh Epic. However, in the Old Babylonian period this is probably an anachronism: the eren tree grows in the mountains east of Mesopotamia.

line 10) Elsewhere the eren tree is also described as the “flesh of divinity.”

line 13) The interpretation of Sumerian ga-ga here is uncertain: it may be the Emesal form of the verb “to bring” or another dairy product. The cattle pen and sheepfold (Sumerian tur3 and amaš) were often invoked in description of the dairy industry and its productivity.

line 20) Sumerian siki ur2 was understood by Cohen as pubic hair, but in conjunction with siki pa it is describing the hair of the head from the base to the tip of the hair follicle (for the meaning, see Couto Ferreira Etnoanatomia y partonomia del cuerpo humano en sumerio y acadio (2009), pg. 108). The verb dub/dab6 may be more technically describing a specific hairstyle worn by young women, embodied by the goddess Inana, as discussed by Mirelman and Sallaberger, Zeitschrift fur Assyriologie 100 pg. 83.

458 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pair of basket-shaped hair ornaments from ancient Mesopotamia. Artist unknown; ca. 2000 BCE (Isin-Larsa period). Now in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. Photo credit: Walters Art Museum.

#art#art history#ancient art#Near East#Near Eastern art#Ancient Near East#Ancient Near Eastern art#Mesopotamia#Ancient Mesopotamia#Mesopotamian art#Ancient Mesopotamian art#jewelry#jewellery#metalwork#gold#goldwork#Walters Art Museum

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Babylonian King Hammurabi (1792-1750 BC)

The Babylonian King Hammurabi (1792-1750 BC)

Episode 14: War and Society in Hammurabi’s Time

Ancient Mesopotamia: Life in the Cradle of Civilization

Dr Amanda H Podany

Film Review

The First Babylonian Dynasty followed the destruction of the Third Dynasty of Ur (which fell following a combined attack of the Amorites to the West and the Elamites to the East) and a brief Isin-Larsa period. The Babylonian Empire devolved from the conquest of…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

The Burney Relief (also known as the Queen of the Night relief) is a Mesopotamian terracotta plaque in high relief of the Isin-Larsa- or Old-Babylonian period, depicting a winged, nude, goddess-like figure with bird's talons, flanked by owls, and perched upon two lions.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Fidget Spinner? Nope — That's a Weapon from Mesopotamia

A 4,000-year-old Mesopotamian artifact that looks just like a fidget spinner and that a museum labeled as a "spinning toy" for 85 years is actually — unexpectedly — an ancient weapon, curators told Live Science.

Museum curators noticed the error while enhancing the Mesopotamian Gallery at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, where the triangle-shaped, baked-clay artifact is labeled as a "spinning toy with animal heads" from the Isin-Larsa period of Mesopotamia.

But though the object may look like a modern-day fidget spinner, museum curators recently realized that it was something else entirely: a mace-head.

The artifact dates to between 2000 B.C. and 1800 B.C. and was made in the ancient site of Tell Asmar, located in present-day Iraq. Read more.

625 notes

·

View notes

Text

Molded plaque with the weather-god Adad and a bull standing on a lion-dragon

Terracotta

Isin-Larsa period, ca. 2000-1800 BCE

Southern Mesopotamia (Iraq)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999.1

#terracotta plaque#adad#mesopotamia#isin larsa#old Babylonian#archaeology#art history#metropolitan museum of art

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Early Dynastic temples

Ten minutes later, he came running across

to where I was still surveying with a large fragment of limestone relief in his

hand, of the sort used for ornamenting the walls of Early Dynastic temples. In

this case therefore, no doubt remained as to where it would be desirable to

start digging: and in fact, three months later there had emerged on this site

the ground plan of the largest Sumerian building yet discovered. And our

antiquities magazine at Tell Asmar was piled high with beautiful objects we had

found among its ruins, (PL. 20) The exact spot where I had put Saleh Hussein to

scrape on that first day, was on top of the high altar in the main sanctuary of

what is now known as the “Shara Temple”.

At Tell Agrab, I used fifty Arab workers,

twenty of whom were our invaluable Sherqati experts. A photographer and an

epigraphist visited me every day that I thought necessary, and all the

recording and treatment of antiquities was done in the lavishly equipped

expedition house at Tell Asmar. On the actual excavation, I was often entirely

alone, moving from one skilled worker to another, whenever they got into

difficulties or finished a particular task. By many today this would be

regarded as a preposterously under staffed operation.

Excavated two previous building

However, I do not myself believe that the

field notes and catalogues from which I produced the final publication lacked

anything in method or detail; and I am convinced that I did not miss any strati

graphical evidence. Over part of the site, I excavated two previous building levels.

However, out of the five hundred or so objects, which were registered, I do not

remember one of which the provenance remained equivocal or whose find spot

could not be exactly placed, both in the plan and in one of the many sections.

It should be added, of course, that this was clearly not a model excavation.

The situation was due to force majeure.

Frankfort, from his headquarters at Tell Asmar, was by this time remotely

controlling excavations simultaneously at Tell Asmar itself, Khafaje and at

Ischali (where Thorkild Jacobsen was recording a temple palace of the Isin Larsa period); so that the

staff of fifteen Europeans and Americans was very fully occupied. However,

illicit digging was beginning on a big scale at Tell Agrab; and, rather than

have it reduced to the state in which we had found Khafaje, it was necessary to

take immediate action.

0 notes

Text

Well, that's it, folks. Wikipedia mod from yesterday's post declares I am wrong because I add actual sources while they invoke gods without intermediaries. Which is somehow "tibetan buddhism." Does anyone know how can I become a ruler of Uruk to rightfully invoke Inanna to ask about details of that Ninisina mess from the Isin-Larsa period to one up them?

Jokes aside, do not use this site for anything. I wanted to prove it isn't like that but most of it very much is.

As a side note I must say I think it's morbidly offensive to call some sort of wacky Jungian faux-neopagan invention "tibetan buddhism," and i'm a person relatively lax when it comes to this sort of stuff!

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Early Dynastic temples

Ten minutes later, he came running across

to where I was still surveying with a large fragment of limestone relief in his

hand, of the sort used for ornamenting the walls of Early Dynastic temples. In

this case therefore, no doubt remained as to where it would be desirable to

start digging: and in fact, three months later there had emerged on this site

the ground plan of the largest Sumerian building yet discovered. And our

antiquities magazine at Tell Asmar was piled high with beautiful objects we had

found among its ruins, (PL. 20) The exact spot where I had put Saleh Hussein to

scrape on that first day, was on top of the high altar in the main sanctuary of

what is now known as the “Shara Temple”.

At Tell Agrab, I used fifty Arab workers,

twenty of whom were our invaluable Sherqati experts. A photographer and an

epigraphist visited me every day that I thought necessary, and all the

recording and treatment of antiquities was done in the lavishly equipped

expedition house at Tell Asmar. On the actual excavation, I was often entirely

alone, moving from one skilled worker to another, whenever they got into

difficulties or finished a particular task. By many today this would be

regarded as a preposterously under staffed operation.

Excavated two previous building

However, I do not myself believe that the

field notes and catalogues from which I produced the final publication lacked

anything in method or detail; and I am convinced that I did not miss any strati

graphical evidence. Over part of the site, I excavated two previous building levels.

However, out of the five hundred or so objects, which were registered, I do not

remember one of which the provenance remained equivocal or whose find spot

could not be exactly placed, both in the plan and in one of the many sections.

It should be added, of course, that this was clearly not a model excavation.

The situation was due to force majeure.

Frankfort, from his headquarters at Tell Asmar, was by this time remotely

controlling excavations simultaneously at Tell Asmar itself, Khafaje and at

Ischali (where Thorkild Jacobsen was recording a temple palace of the Isin Larsa period); so that the

staff of fifteen Europeans and Americans was very fully occupied. However,

illicit digging was beginning on a big scale at Tell Agrab; and, rather than

have it reduced to the state in which we had found Khafaje, it was necessary to

take immediate action.

0 notes

Photo

Early Dynastic temples

Ten minutes later, he came running across

to where I was still surveying with a large fragment of limestone relief in his

hand, of the sort used for ornamenting the walls of Early Dynastic temples. In

this case therefore, no doubt remained as to where it would be desirable to

start digging: and in fact, three months later there had emerged on this site

the ground plan of the largest Sumerian building yet discovered. And our

antiquities magazine at Tell Asmar was piled high with beautiful objects we had

found among its ruins, (PL. 20) The exact spot where I had put Saleh Hussein to

scrape on that first day, was on top of the high altar in the main sanctuary of

what is now known as the “Shara Temple”.

At Tell Agrab, I used fifty Arab workers,

twenty of whom were our invaluable Sherqati experts. A photographer and an

epigraphist visited me every day that I thought necessary, and all the

recording and treatment of antiquities was done in the lavishly equipped

expedition house at Tell Asmar. On the actual excavation, I was often entirely

alone, moving from one skilled worker to another, whenever they got into

difficulties or finished a particular task. By many today this would be

regarded as a preposterously under staffed operation.

Excavated two previous building

However, I do not myself believe that the

field notes and catalogues from which I produced the final publication lacked

anything in method or detail; and I am convinced that I did not miss any strati

graphical evidence. Over part of the site, I excavated two previous building levels.

However, out of the five hundred or so objects, which were registered, I do not

remember one of which the provenance remained equivocal or whose find spot

could not be exactly placed, both in the plan and in one of the many sections.

It should be added, of course, that this was clearly not a model excavation.

The situation was due to force majeure.

Frankfort, from his headquarters at Tell Asmar, was by this time remotely

controlling excavations simultaneously at Tell Asmar itself, Khafaje and at

Ischali (where Thorkild Jacobsen was recording a temple palace of the Isin Larsa period); so that the

staff of fifteen Europeans and Americans was very fully occupied. However,

illicit digging was beginning on a big scale at Tell Agrab; and, rather than

have it reduced to the state in which we had found Khafaje, it was necessary to

take immediate action.

0 notes