WLW, esteemed history enthusiast, Tamamizu Monogatari (and other medieval Japanese literature) purveyor, biggest Ninshubur fan not counting Rim-Sin of Larsa

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Pride Month special 2025: shifts in gender, shifts in character. A Mesopotamian deity triple feature

The following article, in addition to being a pride month special, is also the third installment of a series which started with Nonconformity, ambiguity, fluidity and misinterpretation: on the gender of Inanna (and a few others) and continued in Ninshubur(s), Ilabrat, Papsukkal and the gala: another inquiry into ambiguity and fluidity of gender of Mesopotamian deities. This time instead of looking at the gender of a specific deity or category of deities I’ll instead discuss three remarkable cases in which a deity’s gender shifted: a mourning goddess turned fire god; a second, originally female, Dumuzi (feat. two unique passages which are as close to non-subtextual Inanna f/f as we can get for now - caveats apply); and a divine clerk in the service of Inanna who went from god to goddess without any other apparent changes.

Note that while I previously said this will be the final installment of the series, I have since realized at least one more will be necessary - stay tuned for further updates.

For now, more under the cut, as usual.

From mourning mother to “the handsome one”: Lisin (and Ninsikila)

Lisin already appears in the Zame Hymns from Abu Salabikh (c. 2500 BCE), one of the oldest religious texts presently known. She is the last of the deities listed, and her corresponding cult center is ĜEŠ.GI (reading uncertain), possibly to be identified as Abu Salabikh itself (Manfred Krebernik, Jan J. W. Lisman, The Sumerian Zame Hymns from Tell Abū Ṣalābīḫ With an Appendix on the Early Dynastic Colophons, p. 14). The hymn is fairly formulaic, and doesn’t say much about Lisin beyond her connection with ĜEŠ.GI. She is referred to with the title ama, literally “mother”, though it is unlikely that it should be taken literally. Instead it most likely functions as an indicator of her role as the tutelary goddess of the corresponding city (The Sumerian Zame Hymns…, 46).

A lament focused on Lisin (Lisin A; as you can see here it’s part of the ECSL system, but isn’t actually accessible online), written in first person from her perspective, portrays her mourning the death of an unnamed son, for which she blames her own mother, Ninhursag. She states that this event made her lonely, and that she has no friends or neighbors. The description of mourning itself is fairly formulaic, with all the expected mentions of tearing her own hair, performing lacerations, et cetera. While multiple copies are known, they are imperfectly preserved, and not much can be said about it beyond that (Christopher Metcalf, Sumerian Literary Texts in the Schøyen Collection, p. 52-56).

Lisin’s importance declined by the Old Babylonian period (c. 1800 BCE), if not earlier (Piotr Michalowski, Lisin in RlA vol. 7, p. 33). However, that was not the end of this deity’s history. At an uncertain point after the decline, the name was rediscovered by compilers of god lists. They correctly noticed that Lisin had a spouse, Ninsikila, but that was about it - not even the gender of those two deities was evident to them. Since Lisin typically comes first in older sources, up to the Old Babylonian period (Lisin…, p 32), the new generations of theologians concluded that the former must have been male and the latter female, effectively switching their genders around, as attested for example in An = Anum (Julia M. Asher-Greve, Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources, p. 103). To be entirely fair to them - in Old Babylonian sources listing couples together, such as the Nippur god list, the husbands pretty much always precede the wives (Goddesses in Context…, p. 80). It was a decent guess to make based on evidence available to them.

The cylinders of Gudea (wikimedia commons)

A second factor might have been the phonetic similarity between the name of Ninsikila and that of a goddess from Dilmun (Bahrain) at some point introduced to Mesopotamia (Lisin…, p. 32). Despite actually being named Meskilak, the latter could even be referred to as Ninsikila in Mesopotamian sources, as already documented in the long composition preserved on the cylinders of Gudea (Manfred Krebernik, Meskilak, Mesikila, Ninsikila in RlA vol. 8, p. 94). Lisin also developed a distinct new role as a fire deity in apotropaic magic, though it’s not certain if that first happened after the change of gender or before (Markham J. Geller, Healing Magic and Evil Demons. Canonical Udug-hul Incantations, p. 310; Michalowski favors a late date; Lisin…, p. 33). Through dubious linguistic exegesis relying on alternate sign values and homonymy - a favorite pastime of priests and other similar experts in the first millennium BCE - Lisin's name was provided with a new etymology, too. Both cuneiform signs forming it also had readings pertaining to fire (or at least were homonyms of signs which did), so as attested in an esoteric explanatory text (BM 47463) it came to be explained as “he who burns with fire”, “the burning one” or “he who burns an offering”. A further “translation” which arose as a result of similar inquiries was “the handsome one”, relying on the use of a homonym of the sign SI from Lisin’s name being a logographic representation of Akkadian banû (Alasdair Livingstone, Mystical and Mythological Explanatory Works of Assyrian and Babylonian Scholars, p. 60-61).

A Kassite period depiction of Nanaya on a kudurru (wikimedia commons) One final step in Lisin’s career was the incorporation into the court of Nanaya in Borsippa in the late first millennium BCE (Rocío Da Riva, Gianluca Galetti, Two Temple Rituals from Babylon, p. 192). In a single case, the two of them alone occur in a ritual (Two Temple Rituals…, p. 220). In another, Lisin is just one of many courtiers listed (Two Temple Rituals…, p. 192; Usur-amassu, who will be discussed later, shows up too).

Sadly, as far as I am aware no sources shed any additional light on how exactly the connection between Lisin and Nanaya was conceptualized. It was possible to establish how it most likely developed, though. Nanaya’s temple in Borsippa - the Euršaba (“house, oracle of the heart”) - shared its ceremonial name with a temple of Lisin (Two Temple Rituals…, p. 203). While Lisin’s original Euršaba was located in Umma, a city which didn’t even exist anymore by the first millennium BCE, it continued to be referenced in laments and, most important, has an entry in the Canonical Temple List (Andrew R. George, House Most High. The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia, p. 157). We know that in late periods theological lists could be essentially strip mined for deities to integrate into a city’s pantheon, as well documented in Seleucid Uruk (Julia Krul, The Revival of the Anu Cult and the Nocturnal Fire Ceremony at Late Babylonian Uruk, p. 261). It’s easy to imagine something similar happened in Borsippa as well. The original temple would doubtlessly be long forgotten by the late first millennium BCE, so a priest stumbling upon a reference to Lisin being worshiped there and concluding the local namesake temple is meant instead strikes me as entirely believable.

To be entirely fair, I think there’s a second possibility, though it doesn’t necessarily contradict that proposed by Rocío Da Riva and Gianluca Galetti. One of the rituals pertaining to Lisin’s new role in the Euršaba mentions a cultic installation dedicated to Nabu (Two Temple Rituals…, p. 193). Elsewhere, in astronomical texts, a star named after Lisin (Antares) is associated with Nabu and Borsippa, despite the origin of the name (Hermann Hunger, Lisi(n), RlA vol. 7, p. 32). Zachary Rubin argues that Lisin might accordingly be a stand-in for Nabu in a colophon from Borsippa which lists him together with Nanaya (The Scribal God Nabû in Ancient Assyrian Religion and Ideology, p. 70). However, the cult of Nanaya in Euršaba had no strong connection to Nabu to speak of overall (Goddesses in Context…, p. 282), and as far as I know that is the only house of worship in the city Lisin was introduced to.

From a modern perspective, the gradual shift from a dime a dozen mourning goddess to a one of a kind god certainly might feel almost like trans coding. Ultimately it’s pretty much entirely accidental, though - it’s doubtful anyone involved in Lisin’s theological transformations was aware of the full history of this deity.

(The other) "Dumuzi, she herself": Dumuzi-abzu

Tell al-Hiba, the ruins of Lagash, in 2016 (wikimedia commons) In the third millennium BCE, roughly at the same time when Lisin enjoyed a position of relative prominence in the Zame Hymns, the local pantheon of the state of Lagash included the goddess Dumuzi-abzu. This name can be translated as “good child of the abzu” (Gebhard J. Selz, Untersuchungen zur Götterwelt des altsumerischen Stadtstaates von Lagaš, p. 114). Something that needs to be addressed right off the bat is that the abzu is extremely unlikely to be personified in this case, and it’s virtually impossible Dumuzi-abzu is literally supposed to be the child of the literary character people usually think of today when they hear this term. Prior to the compilation of the Enuma Elish in the late second millennium BCE, which famously pairs Abzu and Tiamat as a theogonic couple, abzu was rarely, if ever, regarded as a deity as opposed to a location (Wilfred G. Lambert, Babylonian Creation Myths, p. 217-218). In a number of sources from between the Early Dynastic and Old Babylonian periods it isn’t even consistently a designation of the watery subterranean domain of Enki/Ea, and might instead be described as mountainous (like in Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta or the hymn Ishme-Dagan D). A variety of sources, including the Temple Hymns attributed to Enheduanna, use it as a poetic term for sanctuaries, making it potentially quite vague depending on context (The Sumerian Zame Hymns…, p. 95). What exactly does it entail in this specific case? Hard to tell, though there were many sanctuaries referred to with the term abzu in Lagash in the third millennium BCE, with Dumuzi-abzu possibly originating in one of them. Furthermore, interpreting the name as “good child of the sanctuary” would be a sensible parallel to fellow Lagashite deity Dumuzi-gu'ena, “good child of the throne room” (Akiko Tsujita, Dumuziabzu. A Goddess and a God, p. 8-9).

Dumuzi-abzu was the tutelary goddess of Kinunir (or Kinirsha), a lost city located somewhere in the proximity of Lagash (Goddesses in Context…, p. 61). We know very little about her character otherwise, though it can be safely assumed that she was closely associated with Nanshe and her daughter Nin-MAR.KI (Untersuchungen zur Götterwelt…, p. 116). Offering lists group her with the likes of Nindara, Ninshubur, Hendursaga and other figures of similarly moderate importance in this part of Mesopotamia (Untersuchungen zur Götterwelt…, p. 115).

At least in Lagash, Dumuzi-abzu’s name could be shortened just to Dumuzi (Untersuchungen zur Götterwelt…, p. 114). Manfred Krebernik actually proposed that every single reference to a deity named Dumuzi in Early Dynastic texts - not just from this one state, but also from sites like Tell Fara - pertains to her, and not to Inanna’s spouse, who at the time would be primarily known as Amaushumgalanna (Manfred Krebernik, Drachenmutter und Himmelsrebe? Zur Frühgeschichte Dumuzis und seiner Familie, p. 163-164). This might be too radical of an approach, though (Gebhard J. Selz, Dumuzi(d)s Wiederkehr, p. 215), and it has been suggested that even in Lagash at least in theophoric names Dumuzi might be, well, Dumuzi (Untersuchungen zur Götterwelt…, p. 116).

As of 2024, it remains uncertain when Dumuzi became the default name of Inanna’s spouse, though first unambiguous examples are available from the Sargonic period, and it can be established with certainty that it was used fully interchangeably with Amaushumgalanna by the Old Babylonian period (Jana Matuszak, Hanan Abd Alhamza Alessawe, A Sargonic Exercise Tablet Listing “Places of Inanna” and Personal Names, p. 37). This doesn’t really change the fact that Dumuzi himself “did not belong to the leading deities in any period of Mesopotamian history” and his inflated modern importance owes a lot to the Golden Bough and similar disreputable sources (Bendt Alster, Tammuz(/Dumuzi) in RlA vol. 13, p. 433-434). This is not the time and place for further exploration of this topic, though.

Dumuzi-abzu was eventually seemingly largely subsumed into Dumuzi, but that only happened after her decline as an actively worshiped deity after the Ur III period, which in turn was a result of the area of the former state of Lagash losing its importance (Dumuziabzu…, p. 11-12). The god list An = Anum from the Kassite period identifies Dumuzi-abzu as a male deity, and as one of the sons of Enki, with no reference to any associations with Kinunir, Lagash, or deities from its pantheon. This is presumably a result of a reinterpretation of the abzu in the name as Enki’s dwelling. The shift in gender meanwhile reflected confusion with Dumuzi (Dumuziabzu…, p. 10-12). Andrew R. George suggests that Dumuzi-abzu came to be understood as a title designating the regular Dumuzi during his annual stay in the underworld, based on a broader pattern of confusion between the abzu (in this context explicitly the domain of Enki/Ea, ie. a mythical subterranean sea) and the land of the dead (The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts, p. 861). The apparent conflation of Dumuzi and Dumuzi-abzu resulted in at least one further curiosity relevant to this article. There is a unique love poem which addresses Inanna’s lover, who is left nameless through most of the composition, as Dumuzi-abzu, as opposed to simply Dumuzi. Sumerian has no grammatical gender, so technically it would not be impossible to translate the relevant passage as if the traditional female Dumuzi-abzu was the target of Inanna’s affection, though obviously this is not exactly a plausible interpretation (Bendt Alster, Sumerian Love Songs, p. 143).

Modern replica of a typical Mesopotamian lyre on display in the Iraq Museum (wikimedia commons); in all due likeness Ninigizibara was envisioned with, or as, a similar instrument Surprisingly, Dumuzi-abzu isn’t the only usually feminine figure who got to replace Dumuzi in the role of Inanna’s spouse in an unusual composition. A single late copy of the lament Uru’amma’irabi (BM 38593) casts Ninigizibara as Inanna’s husband (Wolfgang Heimpel, Balang-Gods, p. 588). Usually this deity was described as a goddess, a harp (or lyre) player and a courtier of Inanna (Goddesses in Context…, p. 115). The unique copy is self-contradictory though, since on one hand an Akkadian gloss interprets Ninigizibara as masculine, on the other the passage itself refers to the deity as a “lady” (gašan), as opposed to “lord” (Balang-Gods, p. 588).

Son turned daughter: Usur-amassu

In contrast with Lisin and Dumuzi-abzu, who both became somewhat malleable simply because they were no longer worshiped, the final major case I’ll discuss is a deity who started as a largely irrelevant figure, but arose to a position of prominence only after their gender changed.

A god named Usur-amassu (“obey his command”, possibly implicitly “obey Adad’s command” given the two are defined as father and son in An = Anum) is first documented in the Old Babylonian period; in other words, roughly when the careers of Lisin and Dumuzi-abzu were already in shambles. As is often the case with minor deities, the earliest evidence are theophoric names, one example being Usur-awassu-gamil. However, it’s worth noting the name was itself a given name in the first place, with prominent bearers including a king of Eshnunna (Paul-Alain Beaulieu, The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period, p. 229)

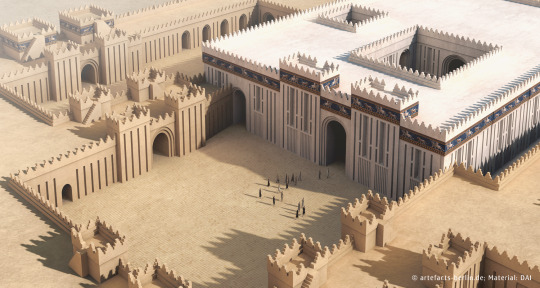

Uruk in the late first millennium BCE (artefacts-berlin.de; reproduced here for educational purposes only, in accordance with the terms of use)

Usur-amassu at some point came to be worshiped in Uruk. The oldest source attesting to this is a short text commemorating the dedication of a field by Kaššu-bēl-zēri, who served as a governor of the Sealand. Sadly nothing about the text makes precise dating possible; however, the element Kaššu is fairly rare in personal names, and was only in the vogue for a couple of decades, roughly between 1008 BCE and 955 BCE (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 225-226). However, in this city Usur-amassu was regarded as a goddess, not a god. This is surprising, as the name is grammatically masculine - and the person “asked” to obey is supposed to be the bearer (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 229).

It should be noted this is hardly the only case where the grammatical gender of a name doesn’t match the gender of a deity, though. As I discussed in the article about Inanna and gender linked in the lead, the name Ishtar is grammatically masculine despite not only functioning as a feminine theonym but even being the source of one of the two generic words for goddess in Akkadian. Looking further, the husband of Nungal, the goddess of prisons, bore the feminine name Birtum (“fetters”; Antoine Cavigneaux, Manfred Krebernik, Nungal in RlA vol. 9, p. 617; I doubt that we are dealing with a Bronze Age equivalent of a he/him lesbian, though I think it would be a fun way to provide this generally irrelevant deity with more personality). There is also the entire phenomenon of nin names, though it is likely that despite being conventionally translated as “lady”, “mistress” etc. this term was initially gender neutral (Goddesses in Context…, p. 6).

To be entirely fair, we do have clear instances of Usur-amassu’s name being partially modified after the shift in gender - the spelling Usur-amassa occurs in Kaššu-bēl-zēri’s dedication and in Neo-Assyrian sources, and while in the Neo-Babylonian period Usur-amassu predominates, this reflects a change in the feminine possessive pronominal suffix in Akkadian, and thus keeps the name equally feminine. The first element was never adjusted, though, and the expected Usri-amassu (or Usri-amassa) is nowhere to be found (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 228-229).

In at least one case, Usur-amassu’s gender was indicated by the use of a double determinative - the standard dingir (“deity”), which prefaced theonyms, was combined with innin (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 228), a variant of Inanna’s name which could also function as a generic term for goddesses, at least in Uruk (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 122).

It might be worth noting that a somewhat similar practice is documented in Old Babylonian Mari, where dingir could be combined with nin for similar purposes. In a single case this created a minor conundrum for researchers, as one of the deities designated this way (to be fair, only in a single source) is Lagamal (“no mercy”; ironically known well from the personal name Lagamal-gamil, “Lagamal is merciful”), who is otherwise firmly a god. Possibly two unrelated deities with the same name arose in two different cities (Gianni Marchesi, Nicolò Marchetti, A Babylonian Official at Tilmen Höyük in the Time of King Sumu-la-el of Babylon, p. 5)

Paul-Alain Beaulieu assumes that the shift in Usur-amassu’s gender had something to do with her introduction to Uruk and subsequent incorporation into the court of Inanna, and that accordingly the name came to be understood as “obey her (ie. Inanna’s) command)”, though he doesn’t pursue this point further (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 229).

One might be tempted to wonder if perhaps the situation has something to do with Inanna’s oft cited association with change of gender (or at least of gender roles). I personally find this implausible. As I already discussed in the first article from this cycle, in sources which were contemporary with Usur-amassu’s arrival in Uruk this ability tends to be invoked in a highly specific, negative context. “May she change him from a man to a woman” and similar formulas appear as a penalty for oathbreakers in royal inscriptions and treaties, as first attested during the reign of Tukulti-Ninurta I. The aforementioned formulas constitute a threat of the loss of a very specific sort of performative masculinity associated with "heroism" or martial valor. More broadly the threat of a change of gender also reflects the fear of a loss of autonomy, something generally tied to masculinity in everyday life in ancient Mesopotamia (Gina Konstantopoulos, My Men Have Become Women, and My Women Men: Gender, Identity, and Cursing in Mesopotamia; Ilona Zsolnay “Goddess of War, Pacifier of Kings”: An Analysis of Ištar’s Martial Role in the Maledictory Sections of the Assyrian Royal Inscriptions).

This is not really a good parallel to Usur-amassu's mysterious "transition". Perhaps most importantly, every single reference to it has humans be affected by the reversal, not gods. There is also no evidence that Usur-amassu was perceived negatively - in contrast with anyone who would hypothetically break a royal oath. Furthermore, nothing really indicates that her role changed alongside her gender. In An = Anum and the incantation series Šurpu the male version is grouped with his brother Misharu (“justice”) and Ishartu (“righteousness”); the sources pertaining to the feminine version from Uruk similarly portray her as a deity of justice, “who renders judgment for the land”, essentially a divine judiciary clerk (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 229). In contrast with martial valor, as far as deities go this role is pretty clearly not really tied to masculinity - or femininity, for that matter (for an overview of judiciary deities and their perception see Manfred Krebernik, Richtergott(heiten) in RlA vol. 11). The change of gender also seemingly didn’t impact Usur-amassu’s preexisting connections, as an inscription from Uruk dated to the reign of Nabonassar explicitly refers to her as a daughter (bukrat) of Adad (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 228).

It’s unclear how Usur-amassu was introduced to the local pantheon of Uruk, but evidently she won over the inhabitants of Uruk pretty quickly. In the Neo-Assyrian period she was one of the deities representing the city during coronations of Assyrian rulers (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 227). In the following Neo-Babylonian period she was one of the five main deities of the city, next to Inanna/Ishtar, Nanaya, Urkayitu (“the Urukean”, an epithet of Inanna turned into a personification of the city) and Bēltu-ša-Rēš (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 179). Thanks to Usur-amassu’s reasonably prominent position in the pantheon of Uruk, she is well represented in the Eanna archives, which document assorted paraphernalia prepared for statues representing her (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 230-244). As a curiosity I feel obliged to point out that in one case a necklace belonging to Usur-amassu was loaned for a festival of Dumuzi (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 335-336). Alas, this evident prominence is not really reflected in publications aimed at general audiences, let alone in popculture. Last attestations of Usur-amassu come from the period of Seleucid rule over Mesopotamia. She retained a degree of importance in Uruk, as expected (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 227). The Eanna actually didn’t exist anymore, but like other deities associated with it she was simply moved to the freshly built Irigal instead (The Revival…, p. 90). Regardless of whether the shift in her gender had anything to do with the primary denizen of both temples, evidently their association was close enough to keep Usur-amassu afloat for the final few centuries of the city’s history.

Postscriptum

This article was initially intended as a pride month special in… 2023? Possibly earlier? I ended up abandoning its original form for a time, and eventually cannibalized its two most major sections, dealing with Shaushka, Ninsianna and Pinikir, for the recent article about Inanna, deities associated with her, and gender. I couldn’t just discard the rest, though, and now you can finally read it all. Much of the information is already on wikipedia through my long term efforts, but now it’s also accessible here, with some extra speculation as a bonus. While this is ostensibly a pride month special, technically none of the sources discussed are really focused on lgbt matters, unless you squint really hard at the two unusual passages I brought up in Dumuzi-abzu’s section. However, I still think the topic of deity gender changes is interesting - if nothing else, it shows that gender was no less malleable than any other aspect of a deity’s character under the rain circumstances. And the process cannot always be neatly explained.

Furthermore, nothing really prevents one from trying to rationalize the changes as a reflection of the respective deities’ identities in a work of fiction featuring them. It’s important to remember that Mesopotamian gods were reinterpreted to meet the needs of new audiences many times, with contemporary institutions, social phenomena or geopolitical developments projected back into the mythical past, especially in literary works (attributing downfall of legendary rulers to insufficient devotion to Marduk is particularly funny, seeing how late his rise to prominence was). Trying to condense Lisin’s puzzling history into something coherent and making him a trans man in the process would thus, arguably, be just a modern example of a similar phenomenon. As long as you don’t alter the content of the actual historical sources, this sort of playful engagement with the material seems more than fine.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

hecatia doodle from an old wip maybe ill finish

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

please don't tag me in random posts especially if the implications are that you don't know how to find my pinned post

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's the final part of the SMT if... design series. We tackle the big questions - what is Zoroastrianism? Did if... really inspire later games? Did you really spend 30 minutes covering the last 6 designs in the game? The answer to all these questions is "Yes", but you'll have to click to find out how.

youtube

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

kind of interesting that while soul hackers is a game from the late 1990s it feels like there's been an increase in rei/naomi as a pairing specifically within the past 5 or 6 years tops

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

there are two more articles coming this month, a pride month special doubling as a third and (for now?) final part of the cycle dealing with mesopotamian deities and gender (this time focusing on Lisin, Dumuzi-abzu and Usur-amassu) and Sisterhood in Context: a Reassessment of Inanna's Descent, an attempt at expanding upon the uncommon but in my opinion not unfounded proposal that the word "sister" is not meant to be literal in this composition. July schedule will most likely consist of the article about shanxiao, Wutong and foxes, and my only SMT contribution this year, a bold proposal that "Asherah" from SJ isn't who the translators (and whoever is in charge of Dx2) assumed she is if tumblr dies, it dies, i suppose; i have no specific plan where to move in such a case admittedly, but i do have more articles planned for even more distant future. stay tuned

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oldest or greatest? Gilgamesh before, in and after the epic(s)

Gilgamesh and Enkidu by Marek Żuławski (via University Museum in Toruń; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

There is no end to grandiose claims about the Epic of Gilgamesh. It regularly gets declared “the oldest” - or at least “one of the oldest” - in many regards: “the oldest story ever told,” “the oldest epic,” “one of the oldest texts” and so on. All of these factoids enjoy considerable popularity both online and offline. It almost feels like this is the entire identity of this work for many - it is The Oldest.

As is often the case with similar statements, the reality is much more complex. The Epic of Gilgamesh isn’t the oldest text, the oldest epic, or even the oldest narrative about Gilgamesh. Depending on how you define it, it’s possible to argue that even calling it the first epic of Gilgamesh is incorrect.

The goal of this article is to briefly explain how it came to be, and why reducing its value to dubious claims about it being The Oldest actually robs it of the source of its value as a remarkable work of literature. Read on to find out what the oldest texts in the world are actually about (fair warning - it might be disappointing), whether kings were divine, Mesopotamians enjoyed, how Mesopotamian literature evolved through the ages, and how all of these factors influenced the history of the Epic of Gilgamesh. Obviously, you will be able to learn a lot about Gilgamesh and Enkidu (and in particular about the development of the nature of their bond), but also about other characters from the Epic - Humbaba (and his long “afterlife” in the least expected places), Ninsun, Siduri and others - as well as those who at some point were a part of Gilgamesh’s history but didn’t quite make the cut - from Gilgamesh’s forgotten sisters to a nefarious Anatolian sea god. You’ll also learn the full history of Sîn-lēqi-unninni - a scribe who left such a profound mark on the story of Gilgamesh that he was later reimagined as his contemporary.

Preface: oldest texts and oldest literature

Dispelling common misconceptions has to start with a quick summary of the early history of writing in Mesopotamia.

Cuneiform was invented in the late fourth millennium BCE, near the end of the Uruk period (Jerrold S. Cooper, Sumerian Literature and Sumerian Identity, p. 1-2). Some 4950 texts from this period have been discovered during excavations in Uruk. A smaller number of unprovenanced ones might have originated elsewhere. Nearby heavily looted sites such as Isin and Umma have been proposed as their possible point of origin. Based on this archaeological data it is assumed that writing was originally invented in Uruk, relatively quickly spread to its dependencies, and then finally across the rest of Mesopotamia (Robert K. Englund, Uruk A. I. Philological. 4th-3rd millennium B.C. in RlA vol 14, p. 446-447). In the slightly less distant past - by which I meant roughly the period from the 1940s up to the early 1970s - the remnants of hyperdiffusionism lingering here and there lead to bold proposals that all writing systems in the world must have been direct descendants of cuneiform. Their proponents argued oracle bone script was somehow derived from cuneiform, despite lack of any evidence whatsoever for the spread of the latter even to central Asia, let alone even further east to China. Maya writing, at the time still considered largely undeciphered, was dismissed as too rudimentary to count as a genuine system to avoid the obvious issue with lack of contact between Mesoamerica and Mesopotamia. Further discoveries of course made this blatantly untenable, and it was already well established by the 1990s that writing was invented multiple times independently. The Mesopotamians were in all due likeness first (though it is possible to make a case for Egyptians beating them to it), but the process which led to the creation of writing was not unique to their culture (Jerrold S. Cooper, Babylonian Beginnings: the Origin of Cuneiform Writing in Comparative Perspective, p. 71).

A typical early tablet from Uruk (wikimedia commons) To put it bluntly, the first surviving Mesopotamian texts are not exactly a thrilling read. The overwhelming majority of them are rudimentary administrative accounts of the activities of individual households and the city as a whole (Uruk A…., p. 448). This shouldn’t come as a surprise, given that writing very likely emerged to accommodate increasingly complex administration and economy in large settlements - chiefly in Uruk, sometimes outright considered the first true city in history (Babylonian Beginnings…, p. 72). The only distinct genre of early texts which doesn’t directly fall into the administrative category are lexical lists. They were teaching aids meant for trainee scribes, who had to familiarize themselves first with the individual signs and then with increasingly more complex vocabulary. They are arranged thematically, with individual examples covering fish, birds, domestic animals, professions, agricultural produce and so on (Uruk A…., p. 448). They only make up around 10% of the corpus (Babylonian Beginnings…, p. 78). Literary texts - as well as many other genres well known from later periods like letters, royal inscriptions, law codes and omen collections - are lacking altogether in the earliest era of writing, and only emerged later (Michael P. Streck, Writing in RlA vol 12, p. 287). The oldest examples come from the Early Dynastic Period IIIa, roughly from the middle of the third millennium BCE (Kamran V. Zand, Mesopotamia and the East: The Perspective from the Literary Texts from Fāra and Tell Abū Ṣalābīḫ, p. 123). Most of them have been recovered from Tell Fara (Shuruppak) and Tell Abu Salabikh, but some come from Adab, Mari (close to the Syria-Iraq border), Ebla (in the proximity of Aleppo) and other cities (Andrew R. George, The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts, p. 4-5). Probably the most famous literary text from the Early Dynastic period are the Zame Hymns - a sequence of 70 hymns, each dedicated to a different deity (Manfred Krebernik, Jan J. W. Lisman, The Sumerian Zame Hymns from Tell Abū Ṣalābīḫ, p. 13-14).

A peculiar subset of early literary texts are the examples of UD.GAL.NUN, an early form of cryptography (Writing…, p. 287). It’s essentially a substitution cipher, though in contrast with the Caesar cipher and the like it appears to combine multiple principles. Signs are variously replaced by ones with similar meaning, phonetic value, or with specific graphic analogies, but none of those rules are universal. We don’t really know what was the motivation of scribes who used it, though it’s worth noting that most of the UD.GAL.NUN texts are relatively long and complex. Only around 2% are learning aids (ie. lexical lists). The remaining 98% are literary, with 23 compositions identified with certainty and numerous fragments on top of that (Kamran V. Zand, UD.GAL.NUN in RlA vol. 14, p. 271-273). While gods take the central stage in the UD.GAL.NUN texts (as they generally do in Mesopotamian narratives), some of them also refer to mythical human heroes. One of the relatively well presented compositions, a myth focused on the travels of Utu (each of them involves a different distant locale and a different person, deity or animal who has to be brought to Mesopotamia from it), mentions Lugalbanda (Mesopotamia and…, p. 133) - arguably the most famous Mesopotamian hero after the protagonist of this article.

It’s worth noting Lugalbanda appears in at least one other Early Dynastic literary text - specifically an UD.GAL.NUN one. In a composition dealing with Utu bringing various other figures from distant locations, he’s one of the “passengers” transported this way (in case you were curious, the other well preserved passages involve Utu’s wife Sherida, as well as Ninshubur). This seemingly anticipates Lugalbanda’s travels through the mountains well known from later literature (Mesopotamia and…, p. 133). Furthermore, a fragmentary narrative deals with the exploits of another human, the warrior EN.UM (possibly also written EN.MES; reading uncertain, in either case), who apparently intended to conquer the city of Arawa, the “bolt of Elam”, with the assistance of Ninura, the tutelary goddess of Umma (Mesopotamia and…, p. 128-130).

“Gilgamesh is the one Utu has selected”: the earliest history of Gilgamesh

In contrast with Lugalbanda and the enigmatic EN.UM, the first possible attestation of Gilgamesh does not occur in a literary text. It has been argued that a certain Gilgamesh-Utu-pada (“Gilgamesh is the one Utu has selected”) is already mentioned in an administrative text from Ur which might come from the beginning of the Early Dynastic period (Gianni Marchesi, Who Was Buried in the Royal Tombs of Ur? The Epigraphic and Textual Data, p. 196-197). Alternatively, the oldest attestation might be an entry in a god list from Fara, which can be securely dated to the middle of the third millennium BCE (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 71).

Note that while I opted to romanize the early form of the name as “Gilgamesh” here, there is some debate over whether it might have been originally Bilgames or Pabilgamesh, and both can be found in modern literature dealing with the Early Dynastic references to him (Who Was…, p. 196). However, this might be erroneous, and “Gilgamesh” might very well be the default virtually for as long as the hero is documented (Gonzalo Rubio, Reading Sumerian Names, II: Gilgameš, p. 8-12). There is some evidence for the pronunciation “Kilgamesh” (replacing /g/ with /k/ in loanwords from Sumerian was common in Akkadian in general), but only as a later phenomenon, best documented in peripheral areas like Emar and Kanesh rather than in Mesopotamia proper (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 81).

The meaning of Gilgamesh’s name remains uncertain too. Interpretations such as “the forebear was a hero”, “the offspring is a hero” (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 74) and “the elder is still a youth” have been proposed (Gebhard J. Selz, Untersuchungen zur Götterwelt des altsumerischen Stadtstaates von Lagaš, p. 105).

Perhaps the most hotly debated early Gilgamesh issue is whether he was a historical figure. Arguments in favor of this view heavily depend on the theories about Enmebaragesi of Kish, as in later literary texts this king’s supposed son Akka (also romanized as Agga; the doubling of the consonant is optional in either case) is an enemy of Gilgamesh (Piotr Michalowski, A Man Called Enmebaragesi, p. 196-197). A hymn from the Ur III period (Shulgi O in the ETCSL) instead alludes to a conflict between Gilgamesh and Enmebaragesi himself (Gianni Marchesi, Nicolo Marchetti, Royal Statuary of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia, p. 99). On another hand, the Sumerian King List casts Enmebaragesi as an adversary of the king preceding Gilgamesh, Dumuzi (Douglas Frayne, Presargonic Period (2700-2350 BC), p. 5). Note this is not the same guy as the more famous Dumuzi

The SKL doesn’t limit itself to presenting Enmebaragesi as an adversary of Uruk and its rulers. It also claims he was responsible for overcoming the Elamite city of Awan (probably located in modern Khuzestan, near Susa), which as per this source controlled Mesopotamia as well for a time (Presargonic…, p. 37). Grandiose claims about his accomplishments can be found in older scholarship as a result, with Awan - a single city - turned into the entirety of (proto-)Elamite civilization (A Man…, p. 196) However, in reality SKL is an inaccurate, ahistorical source - basically a work of fiction. It includes outright mythical figures like Alulim, Etana or Ku-Bau (“Kubaba”), regularly assigns unrealistic reigns lasting centuries to past rulers, entirely glosses over a power as major as Lagash, and only seven names of pre-Sargonic kings listed in it are actually attested in pre-Sargonic sources - and two of them are Gilgamesh and Enmebaragesi… with the latter’s reign lasting 900 years. It therefore is of no use for reconstructing the history of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia (Royal Statuary…, p. 117-118). While the unreliability of the SKL is pretty much universally recognized in scholarship, the same can’t be said about assorted online sources of questionable quality. In particular, be wary of many Wikipedia articles dealing with figures from the SKL - a few years ago a single person taking advantage of the small number of editors in this field completed an utterly insane quest to present every made up ruler as authentic, complete with made up “realistic” dating. That has yet to be fully fixed. Even less reputable sites contain even worse horrors, obviously. While Enmebaragesi is far from the most phantasmal figure from the SKL, it should come as no surprise that it is sometimes questioned if he actually existed. His supposed renown for the most part only comes up in sources no earlier than the early second millennium BCE, in any case (A Man…, p. 197). It’s possible that he was accidentally invented through the misinterpretation of a hitherto unknown text containing the phrase en Mebaragesi - “the exalted Mebaragesi” - referring to a real, if sparsely attested, Early Dynastic ruler known from an unprovenanced inscription (Royal Statuary…, p. 98-99).

An illustration of the surviving fragment of Mebaragesi’s inscription (Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative; reproduced here for educational purposes only).

Through a truly bizarre twist of fate, the aforementioned short text, dated to 2600 BCE or so, is actually the single oldest surviving royal inscription presently known. It’s up for debate if this means the historical Mebaragesi was thus some sort of pioneer. Skepticism is advised, though - Early Dynastic royal inscriptions are generally rare with the exception of the very well documented state of Lagash, so it might very well be a matter of chance preservation and nothing more (Presargonic…, p. 5). The inscription, to put it lightly, is not very informative - it just says that Mebaragesi was the king of Kish (Presargonic…, p. 57). The same name might also occur in text from Tutub in the Diyala valley, though it’s so damaged nothing else can be said about its contents (Presargonic…, p. 56-57). Additionally, given that while technically also Early Dynastic it’s younger by a few centuries, it might very well be that the person mentioned just happens to share the same name as the earlier king of Kish (Royal Statuary…, p. 212). As far as I am aware, the only possible evidence for Gilgamesh’s historicity which has nothing to do with Enmebaragesi is the name of Gilgamesh-Utu-pada. If the reading is correct, it might very well be an example of a reverential name meant to praise a contemporary monarch, similarly to the likes of Uruinimigina-Enlille-izu (“Uruinimgina - Enlil has recognized him”) or Shulgi-Nanshe-kiag (“Shulgi is the beloved of Nanshe”), though those examples only come from later periods (Who Was…, p. 197). However, even Gianni Marchesi, who first identified this name, only tentatively accepts the possibility that Gilgamesh was historical - and rejects the historicity of the rulers from the SKL, even those associated with him (Who Was…, p. 166). In the light of the flimsy, ambiguous character of most of the sources discussed above it should come as no surprise that Piotr Michalowski characterizes the quest for the “real” Gilgamesh as Assyriology’s equivalent of a quest for a “real” king Arthur (A Man…, p. 197). As argued by Andrew R. George, it might very well be that a real king named Gilgamesh existed at some point - though not necessarily one particularly similar to the protagonist of later literary text, just like a possible historical Arthur in all due likeness would not have resembled the king known from medieval chivalrous romances. In any case, whether there really was a historical king named so at some point is of no real concern to his legacy as a religious figure or literary character (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 106; Who Was…, p. 166) - and that’s what matters the most in the context of this article.

“King of the young men”: Early Dynastic perception of Gilgamesh

In addition to debates about Gilgamesh’s historicity, a further subject of inquiries is whether he appears in any of the Early Dynastic literary texts. Most commonly it is asserted that a myth about the first meeting between Lugalbanda and the goddess Ninsun, which ends with their marriage, might have also described the birth of Gilgamesh. This relies on the well attested tradition according to which they were parents. However, the actual text contains no references to the birth of any children (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 5). It’s a very fun read, though:

How many other compositions involving what appears to be a picnic date between a goddess and a mortal, as demonstrated on the screencap above (Jan W. Lisman, The (Inchoate) Marriage of Lugalbanda and Ninsumuna, p. 74-75), are you aware of? No other proposal that Gilgamesh appears in one of the Early Dynastic literary texts attained much traction, and most of them have been conclusively disproved by the early 2000s already. At least one seemingly wasn’t even a genuine scholarly theory, but merely a way to present an unremarkable tablet from a private collection a much bigger deal than it was in reality (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 5-6). While it cannot be ruled out that stories about Gilgamesh were already in circulation in the Early Dynastic period in oral form, no trace of them survives in writing (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 6). This doesn’t mean we know nothing about the early perception of Gilgamesh, though. As I already mentioned, he is listed in the god list from Fara - this at the very least affirms that he was viewed as divine (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 119). An assortment of early references to him as an actively venerated figure are also available from Girsu, a city located in the southeastern state of Lagash, roughly from 2400 BCE. These include entries in offering lists, place names, and the theophoric name Ur-Gilgamesh (“man of Gilgamesh”), though it is an isolated example (Untersuchungen…, p. 105-106). A text from Adab mentions a place known as the “mound of Gilgamesh”, possibly some sort of religious installation dedicated to him (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 123). We also know that mace heads could be dedicated to him, with two examples referring to him respectively as lugal guruš-(e)ne, “king of the young men” (metaphorically “king of the warriors”) and kalag-ga, “mighty one” (Piotr Steinkeller, The Reluctant En of Inana — or the Persona of Gilgameš in the Perspective of Babylonian Political Philosophy, p. 155).

While Gilgamesh’s divinity in all of the aforementioned sources is indisputable, it has to be made clear that the phenomenon of deification of rulers was blown out of proportion in the early decades of Assyriology and needs to be approached cautiously (Piotr Michalowski, The Mortal Kings of Ur: a Short Century of Divine Rule in Ancient Mesopotamia, p. 41-42). While the tangible, historical Early Dynastic kings claimed a “mandate of heaven” of sorts, presenting themselves as appointed by the gods - as best exemplified by inscriptions of Eannatum of Lagash - there’s no evidence anyone deified himself before Naram-Sin of Akkad. And even then, this sort of royal self-deification was the exception, not the rule (Jerrold S. Cooper, Divine Kingship in Mesopotamia: a Fleeting Phenomenon, p. 261).

It’s not clear if Naram-Sin’s successor Sharkalisharri followed in his footsteps in that regard. The evidence is limited to seals of some of his servants and a number of later restorations of damaged passages, but next to none of his surviving inscriptions present him as divine (The Mortal Kings…, p. 35).

The deification of reigning rulers was revived after the fall of the Akkadian Empire under the Third Dynasty of Ur, around 2100 BCE or so (Divine Kingship…, p. 261). It was, confusingly, not actually the third dynasty to rule Ur - nor were any of the earlier local dynasties of Ur regional hegemons. This modern moniker was coined due to excessive reliance on a later literary text - specifically the SKL - in early scholarship. You might occasionally see attempts to rename the period of its reign from “Ur III” to “Neo-Sumerian” and the like, but ultimately the former, awkward as it is, remains the default; and the label “Neo-Sumerian” in particular is arguably hardly an improvement (Alhena Gadotti, An = Anum and Related Lists. By W. G. Lambert and Ryan D. Winters. God Lists of Ancient Mesopotamia, Volume I, edited by Andrew George and Manfred Krebernik (book review), p. 325). While the Ur III period was the pinnacle of the phenomenon of self-deification, to a smaller degree it continued under some of the Old Babylonian dynasties, most notably in Isin. No self-deified rulers are attested past the times of Rim-Sin I and Hammurabi, though. Ultimately being capable of mediating between their subjects and the gods was perfectly sufficient for most rulers, and in contrast with pharaohs the royal was not fundamentally divine (Divine Kingship…, p. 261). Ironically, at the maximal territorial extent of direct Mesopotamian rule under the Neo-Babylonian Empire the ideal ruler was supposed to portray himself as a humble servant of the gods, despite ruling a state extending beyond what his self-deified forerunner from Isin or Malgium would consider basically the entirety of the world (Divine Kingship…, p. 263).

One of the many statues of Gudea created during his reign on display in the Louvre (wikimedia commons)

The fact the first instance of royal self-deification postdates the Early Dynastic period means that even if we accept that Gilgamesh was a real Early Dynastic king rather than a purely literary creation, it’s hard to imagine he was deified while still alive. It has been suggested that if his divinity isn’t simply something fundamentally tied to his status as a fictional heroic figure, the process through which it developed might have been similar to that which led to the deification of Gudea of Lagash (Who Was Buried…, p. 167). Ironically, the two have very little in common otherwise - like other kings of Lagash, Gudea presented himself as a humble servant of the gods, and his inscriptions focus on assorted temple construction projects first and foremost (The Reluctant En…, p. 154). Piotr Steinkeller argues that Gilgamesh as a literary character if anything resembles the Sargonic kings more - possibly in part due to conscious adoption of motifs associated with them (The Reluctant En…, p. 154-155).

While ultimately at best tangentially related to Gilgamesh, Gudea’s reign was one of the most remarkable in the entire history of ancient Mesopotamia. It warrants much more coverage than I can dedicate to it here, frankly. He reigned in Lagash after the collapse of the Akkadian Empire and shortly before the rise of the Ur III state. His posthumous deification was an honor unique to him, and is not attested for any other king of Lagash (Claudia E. Suter, The Divine Gudea on Ur III Seal Images, p. 309). It’s possible that it was in part a way for Lagash to assert itself in the Ur III state (The Divine Gudea…, p. 323). As a matter of fact, references to divine Gudea only start to appear during the reign of Shulgi - the first self-deified Ur III king - which might even mean it was a salient political point (Piotr Michalowski, The Steward of Divine Gudea in Ur III Girsu, p. 191-193).

Most likely the process was gradual, and the veneration of Gudea as a god initially was an extension of standard funerary offerings, which didn’t require the dead to be divine (The Divine Gudea…, p. 310). As you will see later, a myth explaining the circumstances of Gilgamesh’s elevation to godhood is pretty adamant about him actually having to die first, too (Who Was Buried…, p. 166).

“In those days, in those far-off days”: Gilgamesh narratives before the epic

While Gudea’s deification might have been a form of soft resistance to the Ur III state and assertion of pride in strictly local accomplishments, it can be argued that Gilgamesh represents the opposite. The fact he came to play an important role in the Ur III royal ideology is arguably one of the most important, if not the single most important, developments in his history. Starting with the founder of the royal line, Ur-Nammu, the kings of Ur declared themselves Gilgamesh’s brothers and friends. While claiming kinship with a ruler from the distant past was hardly uncommon, the specific terminology used here points more towards the perception of Gilgamesh as a personal deity of the members of the new preeminent dynasty (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 108-109).

It’s possible that stressing the closeness between the reigning kings and Gilgamesh was simply a way to legitimize the new dynasty by evoking the image of a well known legendary figure. It probably helped that Ur-Nammu, despite making Ur, his capital might have been a relative of Utu-hegal of Uruk, who seemingly already experimented with a Gilgamesh-themed royal ideology before the rise of the Ur III state (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 109). While treating Gilgamesh as a god was hardly a personal eccentricity of the Ur III dynasty, its members were probably the only rulers to ever attempt to elevate him to the uppermost echelons of the pantheon. This is best reflected in a short composition detailing the division of responsibilities between the most important members of the official pantheon (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 121-122):

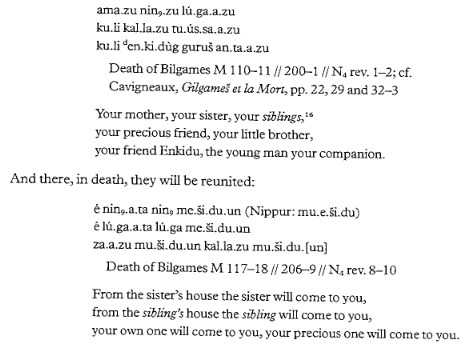

However, the importance of the Ur III period for Gilgamesh doesn’t lie in temporarily elevating him to the uppermost levels of the pantheon. It was instead the appearance of stories about him in written form for the first time. Most likely it was a way to preserve the most popular oral compositions of contemporary courtly bards for posterity. Only one survives in fragments large enough to determine its plot - an early prototype of Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven. However, there evidently were more, as small scraps of tablets which don’t seem to belong to this composition which nonetheless undeniably deal with Gilgamesh’s adventures have also been identified. It is presumed that scribal academies established by the kings of Ur in their capital and in Nippur - which was the religious and intellectual center of Mesopotamia - incorporated the new Gilgamesh texts into their curriculum (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 7). While the Ur III state didn’t last long, and collapsed due to a combination of internal and external pressures, Gilgamesh retained his position in the school curriculum in the following Old Babylonian period. At this point, five individual myths - each of them still standalone - were in circulation: Gilgamesh and Huwawa (two distinct versions, A and B, exist); Gilgamesh and Akka; Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Netherworld; Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven; and The Death of Gilgamesh. Note that these are simply their modern conventional titles, though - in antiquity they were typically referred to with their incipits, respectively Ene Kur Lutilaše (“The Lord to the Living One’s Land…”; the rarer second version was Ialulu, “Anointed One”); Lukingia Akka (“The Envoys of Akka); Šul Mekam (“Hero in Battle”); Uria Usudraria (“In Those Days, In Those Far-off Days”); and Amgale Banu (“The Great Wild Bull is Lying Down”), as attested for example in ancient literary catalogues (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 7-17). Of the five myths listed, Gilgamesh and Huwawa was by far the most widespread, though one of the two versions is much less common than the other. Gilgamesh and Akka and Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Netherworld are not far behind, and evidently also were copied very commonly. Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven and Death of Gilgamesh are comparatively rare (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 8). Most copies of all five come from the eighteenth century BCE (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 7). While written in Sumerian, the five poems about Gilgamesh do not really constitute “Sumerian” mythology, nor are they more “canonical” than the Epic. I repeat this often in posts about Mesopotamian mythology, but “Sumerian” myths are better characterized as myths written in Sumerian - think of the use of Latin in medieval Europe as a good parallel. There is no evidence that a unified “Sumerian” identity ever existed, nor is it possible to separate a “Sumerian” mythology from an “Akkadian” one. The evidence for Sumerian being used as an “ethnic” label is incredibly limited - to the point it might largely be considered a modern concept, not an accurate representation of identity in ancient Mesopotamia (Jerrold S. Cooper, Was Uruk the First Sumerian City?, p.54-55).

Needless to say, the individual Gilgamesh myths didn’t form a coherent whole (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 19-20). They shared the same protagonist, whose personality was more or less consistent, but the same can be said about stories about other human heroes, whether fictional or at least semi-historical, or about gods.

An Old Babylonian copy of the Sumerian King List on display in the Ashmolean Museum (wikimedia commons)

A further text dealing with Gilgamesh which was in circulation contemporarily with the five compositions mentioned above was the Sumerian King List. It might have originally been commissioned by one of the Ur III kings (A Man…, p. 196). If so, it presumably continued to be copied because the rulers of one of the new smaller states, centered in Isin, wanted to present themselves as its heirs, and were keen on seizing the preexisting royal historiography to that end. Needless to say, the SKL’s vision of a past in which one city-state always held authority over Mesopotamia as a whole didn’t accurately reflect history (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 101-102). Much as in the already discussed case of Enmebaragesi, the SKL attributes an unnaturally long reign to Gilgamesh - supposedly he remained on the throne for 129 years. We also learn that his father was a “phantom” (lil - the type of demon which in later incantations answers to Pazuzu. Not very prestigious!). No name is given, though. Furthermore, Gilgamesh is provided with a son of his own, Ur-Nungal, and a grandson, Udul-kalamma, who follow him as kings of Uruk (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 103). He is thus presented as a founder of a short-lived dynasty (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 106). Gilgamesh and his son also play a role in the Tummal Chronicle, though there the latter’s name is Ur-lugal (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 103). This text is yet another scribal school exercise, and while known from Old Babylonian copies, like the SKL it might have been originally composed in the Ur III period. It describes various construction projects in Nippur and nearby smaller settlements supposedly completed by famous legendary rulers, and juxtaposes them with Ur III ones. Some copies add an extra passage meant to present Ishbi-Erra, the first king of Isin after the fall of the Ur III state, as the next ruler to continue this tradition (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 104-105). It’s worth noting Isin wasn’t the only place where remnants of the Ur III royal ideology lingered. In Uruk, which also became the center of a small independent kingdom, the local ruler Sin-kashid invoked Ninsun as his symbolic divine mother just like Shulgi before him, and considered Lugalbanda his personal god. He didn’t claim to be a brother of Gilgamesh, though (Paul-Alain Beaulieu, The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period, p. 107). This doesn’t mean that the memory of Gilgamesh was absent from the considerations of new kings of Uruk, though. An inscription of Anam, one of Sin-kashid’s successors, indicates that the walls of this city were believed to be his work. This tradition is also well represented in later sources. It likely predated Anam, though that doesn’t mean it necessarily reflected historical reality - it’s entirely possible that a connection between the most monumental piece of architecture in Uruk and its most illustrious legendary king developed at some point entirely due to the popularity of stories about Gilgamesh. There’s no real reason to assume that Anam stumbled upon an inscription dating to the times of the genuine Gilgamesh or anything of that sort (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 92). The veneration of Gilgamesh was not limited to kings, as evidenced by theophoric names of commoners, such as Gilgamesh-gamil (“Gilgamesh is merciful”) or Puzur-Gilgamesh (“Protected by Gilgamesh”) and more (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 122). It is also known that he received offerings in Nippur (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 125).

“Surpassing all other kings”: the first epic of Gilgamesh

While the school copies of five myths written in Sumerian are the overwhelming majority of Old Babylonian Gilgamesh literature, a further composition was also in circulation roughly contemporarily with them. It’s not preserved fully, and there are minor differences between the available fragments, but it is safe to say that it represents an early version of the Epic of Gilgamesh. In antiquity it was known as Šūtur Eli Šarrī - “Surpassing All Other Kings” (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 29). However, that still wasn’t the epic modern readers generally think of - perhaps it would be optimal to call it an epic of Gilgamesh. Technically neither Akkadian or Sumerian really had a term with an analogous meaning (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 3). Still, it meets all the modern criteria, so it’s obviously hardly incorrect to call it this way. What is incorrect is to call it a “national” epic, as was sometimes done in the early twentieth century/ To be entirely fair, it is probably justified to apply this label to many epics about historical Mesopotamian kings (like, say, Zimri-Lim or Gulkishar). However, the epic of Gilgamesh was focused not on what made one a Mesopotamian - let alone a citizen or ruler of a specific state - but rather on an universal image of heroism (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 33-34). The most significant difference between this epic and the five standalone myths is that it was not written in Sumerian, the language of scholarship and religious compositions, but in Akkadian, the vernacular across virtually the entirety of early second century BCE Mesopotamia (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 17).

It’s possible that the epic had its origin in attempts at joining together the individual school texts. A unique copy of Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Netherworld from Me-Turan adds two formulaic lines in the end to link it with Gilgamesh and Huwawa, which Andrew R. George interpreted as a possible example. However, it should be noted this was a very rudimentary connection, and no effort was made to integrate the two plots into something coherent (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 16).

Alhena Gadotti goes further and argues that based on shared plot elements, like the presence of Enkidu, travels to foreign lands, and struggle with death and what comes next, it can be assumed that while there never was an epic of Gilgamesh written in Sumerian, all of the Old Babylonian school texts - Gilgamesh and Akka being an exception - formed a loose “epic cycle” of sorts (‘Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld’ and the Sumerian Gilgamesh Cycle, p. 96-99). Paul-Alain Beaulieu instead suggests that all of them belonged to a longer cycle which also encompassed compositions about Enmerkar (who I’ll briefly return to later) and Lugalbanda, which he informally refers to as “the res gestae of Uruk”. However, he sees the city itself, and by extension Inanna (though she is actually absent from Gilgamesh and Humbaba and The Death of Gilgamesh), as its core (The Pantheon…, p. 106-108).

However, it should be noted that the existence of a “cycle” of Gilgamesh from which the epic ultimately arose, while plausible, is not universally accepted (Gilgamesh, Enkidu…, p. 106-107). Even the unique find from Me-Turan mentioned above might not be evidence, if it instead reflects the influence of the epic which arose independently, rather than from joining together the school texts. In this scenario, Šūtur Eli Šarrī would presumably be based on an oral composition which simply shared the motifs with them, though this obviously won’t ever be possible to prove (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 16).

Gilgamesh and Enkidu battling Humbaba, feat. a random onlooker (wikimedia commons) Since the Old Babylonian epic is only preserved in fragments, it’s not entirely certain to which degree it overlapped with the standalone poems. It is only known for sure that a large part of it revolved around the expedition to the cedar forest and confrontation with Humbaba. However, it’s not a translation or even a more or less faithful adaptation of either variant of the school text dealing with these events (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 18-19). This can be easily demonstrated through a comparison of a few basic elements of the plot.

In the standalone compositions Humbaba dwells somewhere in the east, beyond Zagros, in the highlands of modern Iran (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 93). This choice might have reflected a desire to satirize various “barbarian” leaders of states like Hamazi, Simanum and the like which the Ur III state and its successors variously allied or feuded with. Humbaba is thus characterized as boorish and easy to trick (A Man…, p. 205).

This is particularly strongly emphasized in version A, where Gilgamesh initially aimed to trick Humbaba by suggesting he could arrange a marriage between him and his two sisters. The younger of them bears the name Peshtur, possibly “little fig”. It’s possible that she’s an allusion to Peshturtur, one of the daughters of Shulgi of Ur (A Man…, p. 198-199). Peshtur also appears in an uncertain context in Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven. Furthermore, a pun alluding to her might be present in the Tale of Gudam (Alhena Gadotti, Portraits of the Feminine in Sumerian Literature, p. 200), a work to which I’ll return later. Puzzlingly, Gilgamesh’s other - older - sister, who doesn’t appear anywhere else, is named Enmebaragesi (A Man…, p. 198-199). It might very well be that she is supposed to be fictional within the story, and Gilgamesh is essentially mocking Humbaba’s unfamiliarity with royal politics by claiming his rival from other compositions known to both the compilers and the copyists is actually his sister. Granted, it’s also possible they simply interpreted the name as one suitable for a high priestess - a traditional role of royal daughters - since it starts with the same sign as Enheduanna’s and many other royal daughters’ names (A Man…, p. 205). Moving back from obscure branches of Gilgamesh’s family tree back among cedar branches, in the Old Babylonian epic Humbaba guards a forest located in the west of Mesopotamia, rather than in the east. The city-state of Ebla, located in the proximity of Aleppo, is directly mentioned in one of the copies, even. This most likely reflects the influence of historical sources on literary fiction. It is known that cedar wood was already imported from the west, as far as Amanus, during the reigns of the Sargonic dynasty and Gudea. The Old Babylonian compilers must have been aware of that - and thus relocated the supernatural guardian of cedar wood precisely where a Mesopotamian king would be expected to source it from (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 93-94).

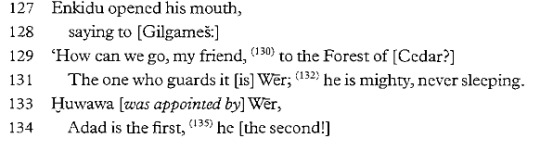

The new western location of Gilgamesh’s expedition is further emphasized by having Humbaba answer to Wer, a weather god worshiped in the north and west of Mesopotamia (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 193). To put it very informally, Enkidu hypes up Wer like he’s the next arc villain in a shonen (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 199):

However, the protagonists never met, let alone confront, him, as far as the surviving fragments go. A unique short god list from Susa might reference this passage nonetheless, since it places a deity whose name isn’t fully preserved but who might be Wer directly before Humbaba. Granted, Gilgamesh is also present in this short extract, and Wer follows him in the well known Weidner god list, so perhaps that’s what is being referenced instead (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 121). Furthermore, an allusion to Wer’s association with the cedar forest might be present in a Neo-Assyrian list of deities worshiped in Assur, which includes a “weather god of the woodland” (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 844). The addition of Wer might not be too important overall, but it does illustrate something quite significant: the early epic wasn't just an adaptation of the preexisting shorter compositions. Its compilers were more than keen on adding brand new material.

Another good example of a minor innovation is the introduction of the alewife Siduri. Gilgamesh meets him when he’s stricken with grief after Enkidu’s death. She essentially tells him he should learn to enjoy ordinary life, though this advice seemingly falls on deaf ears (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 275).

Siduri’s name in theory has a plausible Akkadian etymology - “she is my wall”, to be metaphorically understood as “she is my protection”, well attested as an ordinary given name - but it might instead be a loan from Hurrian. Siduri, “young woman”, is a common title of goddesses in Hurrian sources (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 149) Andrew R. George argues that while her name only survives in two later versions of the epic - Hittite and Standard Babylonian - in all due likeness it was also used in the Old Babylonian one (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 148). However, Gary Beckman notes that the Hittite version actually gives her a different personal name - Nahmazuli or Nahmizuli - and only uses the term siduri as a title. The same pattern seems to occur in the poorly preserved Hurrian version. On this basis he argues she only received her most famous name in the Standard Babylonian epic (The Hittite Gilgamesh, p. 13). Since George’s assumption about her name in the Old Babylonian epic is ultimately speculative, I lean towards Beckman’s assessment.

Something that seems to be almost entirely missing from the popular perception of the epic is that Siduri is firmly identified as a goddess - her name is prefaced by the determinative dingir, which designated theonyms in cuneiform (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 149). This also holds true for her name from the Hittite and Hurrian fragments (The Hittite…, p. 12). Furthermore, appears in strictly theological sources like the god list An = Anum (Wilfred G. Lambert, Ryan D. Winters, An = Anum and Related Lists, p. 162). In a composition conventionally referred to as the Hymn to the Queen of Nippur today, but whose original title Ullâ Šiduri can be translated as “Extol the goddess Siduri”, Siduri functions as an epithet of Ishtar, though this obviously doesn’t apply to the Epic of Gilgamesh, where the name designates a distinct figure (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 149; An = Anum…, p. 176).

While the evidence listed above is abundant, perhaps marveling at the common trend of euhemerizing Siduri shouldn’t be a priority, seeing as a bit over a decade ago an entire monograph about the epic whose author was apparently unaware Ishtar is a deity got published (Alhena Gadotti, Review of Gilgamesh among Us: Modern Encounters with the Ancient Epic by Theodore Ziolowski, p. 728). I suppose Benjamin R. Foster hardly exaggerated when he noted that authors of many non-Assyriological publications about Gilgamesh appear to be “innocent of any knowledge of ancient texts” (A New Edition of the Epic of Gilgamesh, p. 59). In any case, I’m eagerly awaiting new studies of the Iliad which operate under the assumption that this Zeus character is just some guy.

Putting laments about poor quality publications aside, Siduri’s main purpose in the epic ultimately doesn’t have much to do with her divinity, or even with providing sagacious advice. She is merely there to answer Gilgamesh’s request for directions, as he is seeking the survivor of a mythical great flood, Utnapishtim (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 275). The idea of Gilgamesh seeking a survivor of an ancient flood was not new - there’s a brief allusion of a meeting between him and Ziusudra (another name of the archetypal flood hero) in Death of Gilgamesh already, though no Sumerian composition focused on it is known yet (Gilgamesh, Enkidu…, p. 105). While it’s safe to assume the Old Babylonian epic dedicated much more space to Gilgamesh’s encounter with Utnapishtim, the relevant section, which likely was long enough to require a separate tablet, doesn’t survive. Only the next major version of the story provided researchers with more information on its possible contents (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 275).

“He who saw the depths”: the standard epic of Gilgamesh

While the active veneration of Gilgamesh as a god is poorly documented after the Old Babylonian period (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 125), the epic was not forgotten. By the second half of the second millennium BCE versions of it probably derived from the Old Babylonian one reached many distant areas where Akkadian was only used as a diplomatic lingua franca, like Ugarit and Hattusa (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 25-26), where in some cases it could be altered to better suit the tastes of new audiences (more on that later). However, the most important developments were still those which unfolded in lower Mesopotamia. In the final centuries of the second millennium BCE, a major concern of scribes and other specialists was compiling traditional texts into new, canonical “series” (iškar). This wasn’t limited to a single genre, examples range from omen compendiums to literary texts (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 30) - including the Epic of Gilgamesh, which as a result acquired its most famous form, referred to as “Standard Babylonian”. As in the case of many other texts discussed in this article, in antiquity it was primarily known under its incipit - Ša Naqba Īmuru, “He Who Saw the Deep” (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 28). This phrase serves as the title of the protagonist alluding to his encounter with Utnapishtim, who resided in the realm of the god Ea - in other words, in the deeps of the mythical sea Apsu (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 445).

According to tradition the scribes adhered to, compiling this new edition was the work of a certain Sîn-lēqi-unninni (“Sin is one who accepts a prayer”). This is most evident in a Neo-Assyrian catalogue of famous texts and their authors, which attributes the “series of Gilgamesh” - in other words, the Standard Babylonian epic - to this individual (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 28-29). It cannot be ruled out that he was an entirely legendary poet, or a figure historical at best in the way Homer is historical. However, it is evident that for scholars active in the first millennium BCE he was very much a tangible historical person. The fact that his work largely amounted to compiling what was already in circulation doesn’t necessarily mean that he wasn’t himself literally skilled, and that at least some of the innovations of the standard epic can be attributed to him, though this obviously remains speculative (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 30).

We don’t actually know much about Sîn-lēqi-unninni otherwise. His name indicates that if he was a real person, he lived either in the Old Babylonian or Kassite period, with the latter generally regarded as more plausible. As attested for the first time in the seventh century BCE (over half a millennium later), it was common for prominent families in Uruk - especially those of kalû (gala; professional lamenters) and other people involved in scholarly pursuits - to claim to be his descendants. However, there’s no evidence this was rooted in truth (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 30). A unique late source, the Uruk List of Kings and Sages from the Seleucid period, indicates that at least some later members of Uruk’s intellectual elite saw Sîn-lēqi-unninni as a contemporary of Gilgamesh, specifically an “expert” (ummânu) active in his court (Alan Lenzi, The Uruk List of Kings and Sages and Late Mesopotamian Scholarship, p. 142). This obviously makes no sense chronologically - even if we accept that a real Gilgamesh reigned in the Early Dynastic period, Sîn-lēqi-unninni would be about equally distant from him as he was from the dawn of Islam, and ironically much less distant from the late scholars who cast him in the role of a sage from a long bygone era. I’d assume the fact the epic ends with Gilgamesh having an account of his deeds written for posterity (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 446) might have at least in part led to the idea the compiler was actually his contemporary.

Regardless of whether Sîn-lēqi-unninni really was single-handedly responsible for preparing a new edition of the Epic of Gilgamesh or not, it is evident that many changes were made since the Old Babylonian period. The style is much more complex, to the point some translators refer to it as prolix (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 24). Numerous mythological references and philosophical considerations have been added, too. This appears to reflect the shifts in the intellectual life of Mesopotamia. The Old Babylonian Gilgamesh compositions were meant to exalt his heroic deeds. This is par the course for works from a period characterized by enthusiastic, royally backed development of a literary canon focused on stories about deities, heroes and kings performing remarkable deeds. The compiler or compilers later standard edition turned towards a more solemn, contemplative approach typical for their contemporaries. The result is a didactic, moralistic work whose protagonist suffers in order to attain wisdom (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 32-33).

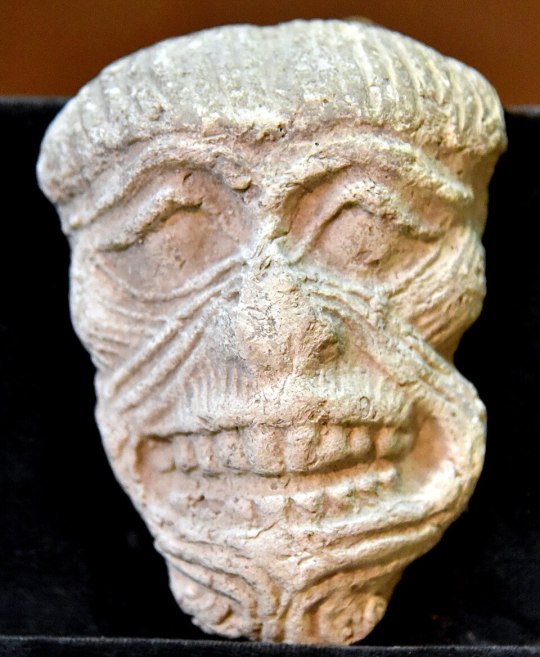

A damaged terracotta plaque showing smiling Humbaba (wikimedia commons) It has to be stressed that despite being a modernization, the new Epic of Gilgamesh still faithfully adapted a lot of the old material. It obviously kept the journey to the cedar forest and confrontation with Humbaba from its Old Babylonian forerunner, though with various changes (Wer is no longer referenced, for example). Furthermore, a detailed passage only discovered recently revealed that Humbaba was essentially presented as a king in his own right, with a “court” of animals entertaining him with music. Given that the same discovery also revealed that the heroes feel guilty afterwards both about killing Humbaba and destroying the forest, it can be assumed that the goal was to further expand on the idea that despite being an “evil thing” (mimma lemnu) who had to be vanquished, he was also a rightful, divinely appointed guardian of his domain (Farouk N. H. Al-Rawi, Andrew R. George, Back to the Cedar Forest: The beginning and end of Tablet V of the Standard Babylonian Epic of Gilgameš, p. 74-75).

A monster-slaying novelty was the incorporation of Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven. As in the case of Gilgamesh and Humbaba and the Old Babylonian epic, we’re not dealing with a translation or direct adaptation, but rather with two distinct stories simply using the same traditional premise (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 471).