#its 1228 now you fool

Text

The typewriter and the typist, in the rain…

So this is my first OC, not perfect, even not good. It's an alternative universe which shits didn't start from 1933 (or not so much), mixed both classic one and DE. I don't want to plague the most of original story, so I only want to put her in background people if I can draw more next year just in case.

Sure the profile contains many grammatical errors. Which one's more difficult, drawing, fighting Omicron and my ADHD, or writing this in English with a help of Google Translate, it's all of above.

No more paper dolls next year, I swear.

I should buy a tablet, the cheapest one, though it won't change anything.

I should finish the game first…

(I may edit the following anytime. Not sure if there are any logical errors.)

About Her

Name: Lucetta Leonforte

Nicknames: Lu, Moon

Alias(es): Moonshine

Gender :Female

Birthdate: May 31st

Nationality: American

Place of birth: Detroit

Current residence: Lost Heaven

Spoken languages: English

Occupation: Assistant of home bakery(day), side work typist of LH Paint & Wallpaper Co.(night)

Eye color: Grey

Hair color: Blonde

Height: 5'7"

Scars: A perforating gun-shot wound on right waist

Sibling(s): A brother (7 years older than Lu)

Father: Lorenzo Leonforte, Enzo the baker, sounds familiar?

Mother: A women from Milan

BACKGROUND STORY

As a third son, Enzo immigrated to America with his wife and his firstborn in early 1900s for some family businesses.

One year later, 3 cugini (Lu's) joined the Leonfortes in Detroit, it was a hard time for everyone.

At some point before 1910, Lucetta was born on a stormy night.

Lu had a bad cold before she could remember, after that she got a husky voice and tears fall out when she sees the sunshine during the daytime. She always wears a hat/8-piece on sunny days when she's outside.

Her mother left them when Lucetta was sick, her parents had a major fight because her mother didn't want herself and her son trapped in this life. Enzo never mentions them again and Lucetta never asks.

In some year of early 1920s, the Leonfortes moved to LH to do a favor for an old friend.

Now they rent a building in Little Italy which used to be an old small hotel (not far from the bar), the first floor is their bakery.

TRIVIA

I heard you paint houses.

"I heard the Leonfortes are good executors, too bad the youngest one's a girl." says an anonymous person.

The side work is working for someone named Baskerville.

Lu's father is a distant cousin of Vincenzo, because I want to so she can call him uncle Vinny LEGALLY.

The Leonfortes are actually doing the bakery business (taste the peach pies), meanwhile they "import" something like explosives and others too complex to say right now. They are not a part of the Salieri family, more like one of the suppliers.

"Best Powder Best Dough" printed on the bakery's front windows.

They have their own delivery cars but also have a fake Rothco's Bakery one, cause they're everywhere in the city.

Lu does some of these deliveries about 3 times a week, bread, cakes, and other things better handled with care.

She only does the deliveries for her family now.

She likes uncle Vinny's business more than her father's.

Some of the side work's outfits are her father's, so don't fit very well.

She loves sitting on a bench near the lighthouse, watching the clouds, the sea waves, thinking nothing.

She's a good listener, usually she won't give any advice.

She hasn't watched the end of Sadie Thompson because she has slept.

Yes, she has a bike.

Family motto (to Lucetta)

Don't in. (Don't get involved in things you can't handle.)

Don't out. (Don't run away from your own family.)

Don't ask. (Don't question the order.)

Don't talk. (Just don't be a rat.)

Don't date with mobs/cops/lawyers/doctors especially shrinks.

Don't get caught.

Don't die. (Be safe.)

"Generally 'Don't do this, don't do that. '" says Lu.

"'I won't put any bread which is made in a factory into my mouth!' says Don Salieri." says me.

#Lucetta Leonforte#OC#my oc#something stupid#its 1228 now you fool#i know nothing about colouring#i dont know how to draw at all#patchdraws

1 note

·

View note

Note

I have a pet octopus named Blinky. Am I fooling myself when I think she is looking at me in the same way I look at her?

A neurosurgeon named Henry Marsh was once operating on a patient’s brain. He looked down a microscope and through a hole in the person’s skull. The patient was conscious and talked to his surgeon because the operation was conducted under local anesthetic. This is often the case for fiddlier brain surgeries. Patients are asked to speak or even play a musical instrument so damage or improvement to these functions during the surgery is easily seen. The patient was watching what Marsh saw via a small television. The surgeon moved one of his instruments to point at a patch of brain on the patient’s left hemisphere. Marsh said, “This is the part of your brain which is talking to me at the moment.” The patient fell silent as he looked at his own brain. Finally, from the other side of the ether screen the surgeon heard the patient say, “It’s crazy.”

The question of what consciousness is like poses all the difficulties of describing the deeply familiar. It has this in common with the taste of milk. What is the best way into this vast topic? If you believe the Universe is a circle whose center is the mind of its percipient then we can safely start anywhere and may as well begin with hands.

The signs one can make with the fingers are quite interesting. These gestures, like many authorless things in the commons of expression, have a buoyancy in them. This carries them away from the moment of their use, up into the symbolic. In this way the peace sign, the middle finger or the thumbs up remain comprehensible even if the hands bearing them are removed from the anti-war protest, the argument, or the moment of encouragement.

It was exactly this buoyancy that led the 10th century citizens of Pistoia in Northern Italy to carve two disembodied marble hands, each giving the fig. This is a very old gesture of insolence that represents the female genitals, where the thumb plays the part of clitoris (make a fist and slip your thumb between the index and middle fingers.) The marble hands were raised to the top of the tallest tower at Carmignano castle and aimed at Florence (the hereditary enemy). These hands remained the symbol of Pistoia’s independence for hundreds of years after. When Florence eventually conquered Pistoia in 1228 the first term of their peace was the tower’s demolition.

But even in this example—where a gesture has been so abstracted from particular hands on a particular person as to be severed, set in stone and elevated to something like a political identity—there is one aspect that can’t rise above and out of the moment: the pointing. The offensive hands were pointed at Florence. In doing this the entire city of Pistoia formed itself into a single person whose pair of hands expressed that civic person’s focused indignation.

The fig, like the finger, the thumbs up or the peace sign, can become an entity unto itself. The peace sign can do its work indifferently and doesn’t care if it’s in a text message, on John Lennon’s arm at the foot of the Statue of Liberty, or produced ironically by soldiers in a candid photo. In their indifference these gestures have a great deal in common with words. Strings of words can express intense betrayal or commitment, the feeling of hope or its escape through our fingers, the way we want the check split. But words themselves, string withdrawn, are so indifferent to us and the moments of our lives that when it comes to assembling definitive lists we find their initial letter the most appropriate way of sorting them.

But pointing is different. You can imagine a pickled lexicon of hands, hands severed in the moment of relating optimism or indignation—hands preserved in salt, to be dusted off when we next needed to express those feelings. Obviously this is more Genghis Khan than Noah Webster, but imagine the store room where these hands are kept. The thumbs up now seems ghoulish, the peace sign bitterly ironic and the middle finger entirely appropriate. These gestures are indifferent to their location and readily appear to mean something in any context. But what does the pointing hand express? What is a pointing hand when we cut the invisible nerve connecting the tip of its index finger to a desired object? The image of 9/11 that most haunts me was taken by the photojournalist Todd Maisel. It is of a severed hand he found in the street, pointing at him as it lay next to a single segment of Hershey bar. Like an empty theater, there is something mysterious about a hand that points to nothing.

Pointing, like every gesture, is an instantaneous sculpture the mind makes of its present state. This is necessary because each person’s mind is secluded by an absolute privacy. Our minds, such as we ourselves know them, can only be Morsed out to others through representations like gestures, kisses, silence, and speech. The temptation to examine the physical analogies the mind makes of itself in order to see what can never be seen of a person—their mind as they experience it—has proven irresistible.

A German psychologist called Franz Brentano seized on this in the 1870’s. He proposed that the essential difference between a mind and everything other kind of thing in the Universe was that minds could point. This has come to be called intentionality. Brentano put it like this:

Every mental phenomenon includes something as object within itself, although they do not do so in the same way. In presentation, something is presented, in judgment something is affirmed or denied, in love loved, in hate hated, in desire desired and so on.

This [...] is characteristic exclusively of mental phenomena. No physical phenomenon exhibits anything like it. We can, therefore, define mental phenomena by saying that they are those phenomena which contain an object intentionally within themselves.

In other words, the contents of a mind are woven so tightly into the activity of a mind as to make it extremely difficult to talk about one without the other. Attempting to clip away one’s loving and the person to whom it refers—hoping to leave visible the intentionality that mediated the connection—would produce something approximately as grotesque, wistful, and mysteriously empty as the severed hand that points at nothing. Saying the mind points and calling this a characteristic activity of all minds is one thing, but the analogy yields a strange and frightening result when it is forced to describe a mind bleached of its contents. That is, when it is forced to describe consciousness itself.

You might say—very reasonably—that a mind never exists separate of the content of which it is conscious. If we excuse the edge cases of Buddhist nirvana and cogito ergo sum then this is probably true. Unfortunately, it is the quest for exactly this strange and frightening result that has driven the biological study of consciousness. You can get an idea of where things have been heading by looking at a recent study of cuttlefish camouflage.

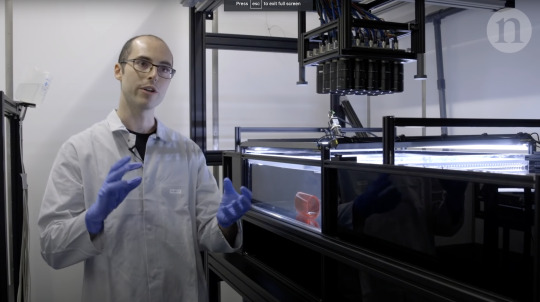

Biologists at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research in Frankfurt realized something about the way these animals disguise themselves. It seemed to open a window into the neural pathways whereby the cuttlefish convert what they see into what best prevents them from being seen. Cuttlefish camouflage, along with that of octopuses, is by a very long way the most sophisticated found anywhere in the animal kingdom. Cuttlefish skin contains several million sacs of pigment, each of which can be individually stretched or contracted by muscle cells. This display organ is under the direct control of the brain and can completely alter the animal’s appearance in only a few tenths of a second. The crude analogy for us would be voluntary control of gooseflesh, whereby we could spell out words in any font we liked or for that matter depict memories by selectively erecting the hairs on our body.

Now, if you have a black box like the cuttlefish brain, whose secrets and techniques you would badly like to understand, there is an obvious strategy: control what the cuttlefish sees and carefully watch its reaction. If the unknown means by which the cuttlefish decides on a camouflage can be trapped between something you cause and an effect you record, it ought to be possible to infer a great deal about how its brain works.

The Frankfurt researchers accomplished this man-in-the-middle technique essentially by forcing cuttlefish to swim across a Kindle that displayed known patterns while recording from above the camouflage decisions these provoked. Their setup allowed each sac (also called a chromatophore) to be numbered and its dilations or contractions tracked individually over time. The research is still in an early phase but the goal is very clear: extract the method by which the cuttlefish brain has solved the problem of recognizing its environment and mimicking it.

Cuttlefish are able to camouflage themselves virtually from the moment they hatch. This implies two facts. First, that the method is in-born and genetically heritable and second, that because the method is genetically encoded it must be a relatively simple solution. This simplicity is tantalizing. It requires powerful computers, our most advanced artificial intelligences and hundreds of thousands of attempts even to begin to reproduce what an animal the size of a hen’s egg can do in a tenth of a second. All the operations that go into producing an effective camouflage—analyzing textures, finding edges, and displaying the average of what surrounds you—turn out to be extremely difficult problems for us. Problems to which our only answer at present is brute, computational force.

Whether or not this research will harvest a more efficient solution from the brains of cuttlefish remains to be seen, but the principle is as old as modern science: a method must be extracted from the place in which it operates, extracted and put to work for the relief of man’s estate. That's been the stated purpose of science since Francis Bacon first proposed the formulation in 1605.

Sadly, it is not difficult to say which men and whose estate will benefit from this relief.

Economic forces are aligning that give this research and others like it a depressing and sinister aura. Right now the second most profitable division of IBM is its “cognitive solutions unit.” This is a consultancy that helps other businesses identify inefficiencies (i.e., humans) that can be eliminated by automation. Something like 40% of all jobs presently occupied by people are expected to disappear in the next 15 years as machine learning becomes more adept at shuffling paperwork. Businesses that employ thousands of people in administrative departments are expecting automation to reduce these white collar salary burdens (i.e., humans) to 1% of their present level.

The software agents that will make possible these efficiencies of automation are not intelligent in any sense of the word; each agent will be a method for performing an arbitrary task that becomes less clumsy the more iterations of the task it performs. The millions of iterations these programs must run to achieve anything like proficiency at their assigned task makes these methods immensely cumbersome and very difficult to debug when they go wrong. Anyone who has spent time trying to make a machine learning agent work as well as the person whose capacities it is meant to imitate will instantly perceive the benefit of research that cops a solution from biology, where the millions of optimizing iterations have already taken place via natural selection.

Even with the primitive methods we now possess there will be only one historical analogy for this revolution in efficiency and that is the first Industrial Revolution. In the early 19th century the mechanization of cotton cloth production was so fabulously efficient, compared to traditional methods, that the profit margins of newly industrialized weavers were not 10% or even 20% per year but something closer to 10,000%. Needless to say, when efficiencies and profit assume these revolutionary magnitudes human misery follows it like a shadow. Given the economic forces that presently rule the world our complete failure to understand consciousness either analogically or literally is probably more of a blessing than a hindrance to humanity’s estate.

These economic forces require people for its extension and development, but they are no more essentially human than tapeworms are food. This state of affairs—beholdenness to parasitic forces that determine our history and perhaps large parts of our selves—makes the immunity of consciousness to description all the more painful, and our facilitation of these economic forces all the more complicit. Surely, we think, if we could reach up and grasp the awareness that can never be seen, because it is the seat of seeing, the loneliness that breeds so readily within it would not be as painful. The loneliness that is the mysterious accelerant of profit in a society of atomized consumers.

The privacy of minds from each other, and the loneliness it engenders, is one of the great immaterial conditions of human life. Most people are compulsively expressive in reaction against it. The human mind is almost defined by its expressiveness, and by its incredible surplus of this ability compared to the tasks survival demands. So much so that there is a serious account of language as an evolutionary force in itself. On this interpretation, humanity has become steadily less aggressive over time because language allows less belligerent humans to conspire the premeditated murder of the most tyrannical. Over thousands of generations, it is thought, language allowed evolution to select for highly cooperative and verbal, if ultimately cold-blooded, individuals.

Language often seems to beget its own surplus. I think of John Milton—blind, irritable and old—bleating, “I want to be milked!” as one of his daughters sharpened a quill to take the morning’s poetry dictation. Or even better, the nameless master of Englishing one’s feelings who first said of a talkative person, “I couldn’t get a word in edge-wise.” This phrase is at least two hundred years old. Its metaphor of turning a word to present the thin edge to a conversation is thoroughly dead. Nobody who uses it expects to be appreciated as witty. Yet we still recognize the frustrated state of mind that coined the phrase, and this keeps the dead metaphor in currency.

Recognition is an even better example of the mind’s reaction against its own privacy. Perhaps even more than they are made to speak our minds seem built to recognize one another. This power to recognize entities like ourselves runs through seeing a face in something like (ツ), past our revulsion at corpses and too-realistic robots, all the way to one of the most remarkable recognitions of mind it is possible to have.

A marine biologist called Jean Boal studies cephalopods at a university in Pennsylvania. She told a story to an Australian philosopher named Peter Godfrey-Smith, who relates it in his book Other Minds,

Octopuses love to eat crabs, but in the lab they are often fed on thawed-out frozen shrimp or squid. It takes octopuses a while to get used to these second-rate foods, but eventually they do. One day Boal was walking down a row of tanks, feeding each octopus a piece of thawed squid as she passed. On reaching the end of the row, she walked back the way she’d come. The octopus in the first tank, though, seemed to be waiting for her. It had not eaten its squid, but instead was holding it conspicuously. As Boal stood there, the octopus made its way slowly across the tank toward the outflow pipe, watching her all the way. When it reached the outflow pipe, still watching her, it dumped the scrap of squid down the drain.

The story is striking not because of how human (and even petty) the octopus seems but because of how anyone hearing it feels helpless not to recognize a mind at work.

Obviously this anecdote is not scientific research, nor objective proof of a mind—or even of intelligence. The inherent privacy of minds makes their rigorous study a frustrating game of inference, and this only becomes truer the less related we are to the animal under investigation. Even now, though we can look into the human brain with the full battery of medical imaging technology, there is no objective difference between a mind that is dreaming and one that isn’t. Scientists who study dreams have used the same method for decades to determine if one is taking place: they wake their subject up and ask if they were dreaming. In rather the same way intelligence is flexible and therefore difficult to define, minds are private and so, hard to prove.

It is very strange that octopuses, cuttlefish and one or two types of squid are even suspected by scientists—or felt by us—to have anything like a mind. Our last common ancestor with our closest living relative (the chimpanzee) lived around six million years ago. This proximity goes a long way to explaining the similarity of chimps to ourselves. We both use tools, lead highly social lives and have extraordinarily long infancies during which our large brains slowly mature. There is no direct evidence our common ancestor shared these properties but given the fact that humans and chimps both inherited these sophisticated traits, it seems very likely that it did.

The last common ancestor of humans and cephalopods lived 600,000,000 years ago. It is quite certain this ancestor shared very few traits either with ourselves or with cephalopods. This animal was probably a flattened worm, only a few millimeters long and very nearly brainless. Humans and cephalopods inherited virtually nothing from this ancestor more sophisticated than basic molecular biology (very basic: cephalopod blood is blue and relies on copper to bind oxygen rather than the iron in our hemoglobin.)

Despite this, each has evolved a complex brain and an intelligence that, in the case of octopuses, is so devious as to pose real difficulty to their successful captivity by planet Earth’s dominant species. Godfrey-Smith writes,

Captive octopuses often try to escape, and when they do, they seem unerringly able to pick the one moment you aren’t watching them. If you have an octopus in a bucket of water, for example, it will often look content enough in there, but if your attention strays for a second, when you look back there will be an octopus quietly crawling across the floor.

If your soft body offers a meal that’s nearly pure protein it’s very advantageous to know when you’re being watched. However, octopuses are often stunningly incautious around humans. Aristotle noted their blitheness, saying they “will approach a man’s hand if it is lowered in the water.” This is not an exaggeration, especially if a wild octopus is used to your presence. Godfrey-Smith describes a dive in Australia when “an octopus grabbed [a researcher’s] hand and walked off with him in tow. [The researcher] followed, as if he were being led across the sea floor by a very small eight-legged child. The tour went on for ten minutes, and ended at the octopus’s den.”

Lab research has confirmed that the giant Pacific octopus can recognize individual humans by sight, even when the octopuses had never seen these humans dressed in other than identical uniforms. Something similar seems to be true of other cephalopods. A Canadian researcher described “one cuttlefish who reliably squirted streams of water at all new visitors to [her] lab, and not at people who were often around.” This remarkable talent for recognition can actually invalidate behavioral research, which depends on the assumption that the subject is reacting to the experiment you’ve designed and not to the person conducting it. Perhaps tellingly, the Frankfurt camouflage investigators do not mention controlling for this recognition.

Many researchers of cephalopods report a sense of presence with these animals; and these are people for whom it can be quite inconvenient to have very strong, subjective impressions of experimental subjects. Nevertheless, some are moved to assign remarkable degrees of awareness. Godfrey-Smith quotes one researcher as saying,

When you work with fish, they have no idea they are in a tank, somewhere unnatural. With octopuses it is totally different. They know that they are inside this special place, and you are outside it. All their behaviors are affected by their awareness of captivity.

To be the subject of attentive perception is a very particular feeling. For humans, this kind of attention—whether it emanates from a pet dog, your mother, or a cop—is very difficult to distinguish from the feeling of being recognized as more than a physical phenomenon: recognized as the kind of thing that deserves, respectively, the extraordinarily subjective attentions of loyalty, love, or suspicion. And a reasonable working definition of a mind is that it is the kind of thing which merits, and can appreciate, attentions like these.

Hence, it becomes harmful and unilluminating to imagine a mind by itself—let alone to search after an isolable method by which the solitary mind generates awareness. Seen in this way, minds exist to recognize one another and minds exist through these recognitions. That is, the thing that makes a mind more interesting than any other feature of the brain is that its center of gravity does not lie in the skull.

Almost everyone understands this on an intuitive level. That’s why, for example, the lonely and selfish agent on which most economic models of human action depend requires several years of high-level academic conditioning to take seriously. These economic agents, like their counterparts in machine learning experiments, have a peculiar and obvious mindlessness. Each of these models of mental activity is not only empty of meaning but haunted by a ghost of intention. This is the same ghost and the same uncanniness present in the severed hand that points at nothing.

This bears repeating. Our species’ keenest minds created a model of human activity to describe our behavior and this model is a less convincing portrayal of mental life than the one we cannot help but see in this planet’s smartest mollusk. Think of the cosmic rebuke to our own powers of self-awareness this implies.

If I try to imagine my own thoughts while being led, hand in tentacle, on a leisurely tour of the seabed around an octopus’ home those thoughts would be from a poem. 350 years ago a poet called Andrew Marvell came up with a famous analogy about the nature of minds. He said the mind was “that ocean where each kind / does straight its own resemblance find.”

Whether cephalopods have a mind in this or any other sense is probably something that must be passed over in silence. However, the fact that certain of them are able to provoke the feeling of recognition on anything like our own terms is an extremely important result. The last time we had anything neurological in common with these animals was more than half a billion years ago, when each of us was a worm and quite unprepared to recognize anything. There is no shared inheritance of mind, as we have with fellow primates, priming us for this recognition. Yet in a few cephalopods Nature has conspired to produce something that grips with the special grasp one mind has for another.

If it is true that you can’t mow the lawn with a blade of grass, and the human mind truly is beyond its own comprehension, moments of recognition like these may be as close as we ever get to ourselves.

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

I went with ANGST because that’s what I was feeling lately. Also, Deacon in his feelings? yes. Does this fic set up the possibility for me to write some reunion goodness? also yes 👀👀

From this prompt list: The jittery, sick feeling when you can’t do anything

Deacon x Madelyn Hardy (Agent Charmer)

1228 words (under a cut) | [read on Ao3]

Charmer had only been gone a week—traveling North to Far Harbor with Nick Valentine—before Deacon started going stir-crazy. The first few days had been easy with lots of work to do with the Railroad, even if they were simple jobs better suited for tourists and newbies. He ran dead-drops and delivered resources to safehouses, scavenged the abandoned buildings for supplies to return to HQ. But by the eighth day, traveling alone left him with a hollow feeling in his chest. It didn’t matter that he had spent years by himself, running Railroad ops across the Wasteland. Back then, he preferred to do things solo, found it easier to compartmentalize his emotions and avoid forming interpersonal connections. He didn’t like to think that he was co-dependent but that was before he had a partner.

Before Charmer.

Deacon had gotten so used to her presence in the last year and a half that not having her around was more of a shock to his system than he was prepared for. Waking up alone was an increasingly difficult task, reminding himself as the dreams flittered away and he stared at the empty space in the bed that she wasn’t just loitering in a different room. He craved her touch—it wasn’t all lewd—yes there were a lot of lonely mornings and desperate nights where his own hand paled in comparison, but what he desperately wanted was intimacy.

Charmer was by nature a physically affectionate woman, even before their relationship became romantic. She knew how to express herself with words, could charm anyone with a smile but thrived on simple gestures and little touches. Her soft fingers interlaced with his, brushing along his brow or against his pompadour wig (teasing him to grow out his natural hair so she could run her fingers through it), palm flat against his chest so she could feel his heartbeat—or tapping playfully against his nose. He wondered now that the sensation was missing again, how he had gone without it for so long.

And why he was still so chicken shit to tell her how he felt more often than not. He’d said the words—told her he’d loved her—but he could count the number of times on both hands. Charmer had him outnumbered by hundreds. Now that she was gone and he was unsure of when he’d see her, or when he’d hear her voice again, an unsettling panic rose up in his gut. Suddenly he was worried if he’d be able to ever tell her the words again, given the chance.

By week three, he was pacing around Railroad HQ aimlessly, bones and mind aching from a lack of sleep. There had been no word from Charmer or Valentine—or any of their agents up north, for that matter. The radio silence was beginning to eat at his resolve, so much so that he passed off any assignments to the other operatives available, just so he could watch for Drummer Boy’s dead drop arrivals, wanting to be the first to learn of any news. When week four began, he very nearly chartered a boat to Far Harbor himself before Dez reeled him in, sending him to Ticonderoga for a change of scenery.

At the safehouse he still paced, sick with anxiety—High Rise held a mix of amusement and frustration over the situation, calling Deacon a lovesick fool, but proud of him for having something good in his life to live for. Then promptly booted him to watch duty on the street where his pacing would be less distracting and more useful.

Through the lonesome weeks he had been smoking through more packs of cigarettes than was likely rational for any person—blowing through what little caps he carried with him to keep his supply steady. Charmer wouldn’t’ve been pleased, sticking a bright piece of pink gum between his teeth before she came anywhere near his mouth for a kiss. So for five days he didn’t smoke, even as his hands trembled around the stock of his rifle and his stomach lurched, nearly impossible to keep a bite of food down. On the sixth day—day thirty-six of her absence—he broke, but savored a single smoke back on the roof of the Old North Church, looking down at the etchings they had left in the stone with her pocket knife.

Mads—she had insisted, easier than Charmer. + D—he wasn’t about to leave his full name. More mysterious that way. It was silly and reminded him of something a pre-war couple might do in those romance novels she liked to read, or the drive-in films only she could retell. So High Rise was right—he was a sentimental chump who had managed to fall in love in the middle of a war—but now the Institute was gone, and he deserved to have those lazy days he always dreamed about. And Deacon wanted to spend them with Charmer.

On day forty-one, Deacon sat in one of the downstairs pews of the church, just staring up at the tattered ceiling. He wasn’t necessarily praying—was there even a God to pray to anymore—but was deep in contemplation. He was thinking about Charmer, hoping that by some divine intervention, his thoughts might reach her. Even with the amount of time that had passed, and the continued silence that alarmed the group, the thought that she had died never crossed his mind.

He wondered if she looked any different—he certainly did—had finally taken her advice and grown out his natural hair a little more than where it was the last time she saw him. He’d gotten some new clothes too—different than his usual rotation of disguises—but something a little more comfortable, domestic even, and a heavier jacket for colder climates—just in case. Maybe Charmer had grown her blonde curls out, or cropped them? Was she still wearing that same shade of bright red lipstick? Of course she was—he smiled at the rafters, imagining her grin, her laughter and could’ve sworn he heard her voice, but when he looked over his shoulder, all he saw was Drummer Boy.

“I have something for you,” he greeted.

“Salvation?” Deacon joked.

Drummer Boy pulled free a holotape from his jacket and flashed a knowing smile. “I just received this from a runner—was supposed to be delivered weeks ago but changed too many hands on its way south.”

Deacon immediately stood, the headrush momentarily blinding. He could infer what—and who the holotape was from, and his heart raced in anticipation. Before he could speak, or ask, the Railroad messenger was nodding. “I’ve already sent word back to Far Harbor that they can anticipate an in-person liaison within the week.”

Holotape in hand, Deacon felt his world come back into sharp focus so rapidly it was dizzying. A fluttering excitement he hadn’t experienced threatened to burst his heart right out of his chest. He inferred from Drummer Boy that he’d be the one making the trip to Far Harbor—but it wasn’t like he would let anybody else go in his stead. He’d spent forty-one days alone—would have to spend a few more traveling north to get to her, but it would be well worth it in the end.

He’d be with Charmer again soon enough.

#fallout 4#deacon x f!solesurvivor#madelyn hardy#otp: my hovercraft is full of eels#deacon x mads#drummer boy#because i love to give drummer boy a cameo#gaybabylegs

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

surefire ( poe x ofc x kylo ) AO3

II. Kylo - read part one here

a/n: very internal monologue heavy on kylos end, but hey, he’s got things to internally monologue about. next chapter is our girl Amicea who I have “casted” as Emilia Clarke in her role of Daenerys from GOT, i’ve taken some inspiration from that roll, but i’m hoping not too much. I forgot too, this is pre TFA so kylo is pretty conflicted here as the dark side is new to him. Enjoy!

wc: 1228

tw: none, just kylo being kylo

tags: @treestarrrrrrrr

II. Kylo

On board the Supremacy, Kylo feels unease. People scramble out of his path without him even sparing a glance. He thinks that this is what power feels like, he thinks that this is the way to restoring what came before and righting the wrongs he has faced. While he creates unease around him, this ship is the one place where he feels closest to what a home should be.

“Prepare my ship.” He orders to a nearby lower officer. He’s heard unsettling rumors about his bride to be, and he intends to settle them himself. On the way down to the planets surface, he thinks of his mother. His intended, Amie- No, Amer- no, Amicea, that’s it, reminds him so much of her, and it drives him up a wall, and opens the gaping canyon that is his conflict by at least ten feet every time she speaks.

But all this thinking does nothing to prepare him for the sight of her. She’s sitting in the lesser of the two throne rooms, on a beige stone bench, reading. Her attire has changed since he last saw her. She’s abandoned her white gown for a black one, draping across her sides. He almost thinks its poetic, how she's abandoned her light for the black. He almost thinks its funny, because he can tell the black dress doesn’t mean she’s convinced of the order, almost like how his mask can hide his own uncertainties. Just almost though.

“Your Majesty.” He addressed her, he didn’t bow, and he could hear his mother's incessant nagging in the back of his mind.

“Your excellency.” She stood, and set her book on the bench beside her. “I heard you were on your way down.” She smirked, she still looked at him with distrust, and Kylo realizes she is less of a fool than her advisers make her out to be. The last time he was here, he saw her with others, she was warm and welcoming. Her family sigil is a bright phoenix, and around her handmaidens and friends, they seemed to be wrapped in the bird’s fire. But to him, he felt like a shriveled flower in the winter, waiting for the sun to drape over him. He longed for something of substance, not just the empty that the Supreme Leader expected of him.

“I’ve heard unsettling rumors.” He began, he thought he saw her eyes roll but that could’ve been the light, or at least that’s what he was going to tell himself. “About a visit you received from a New Republic pilot.”

“Ah yes, Commander Dameron.” He was taken aback by her honesty. She was hiding a smile, that same smile that bathed others in love, the smile he wished he knew. She began to walk to a small table with wine glasses. “He came to beg me not to marry you. Wine?” She offered. Kylo stumbled, he expected lies.

“No, thank you.” He was thankful for the mask in these moments. “Why is that?” He watched as she picked up her glass.

“We’re old friends, and he’s loyal to the New Republic.” She shrugged and took a drink. There was more to that answer, but Kylo knew not to push, at least not for now. She sat back down at a table in the corner, and gestured for him to join her. He obliged and sat across from the young queen. “Is that all, Commander Ren?”

“Yes.” He made eye contact with her. They were blue, like the calm seas of Chandrila, where he was born, no, he stopped himself, where Ben Solo was born. Ben Solo is dead. He reminded himself. “Do you have anything for me, Your Majesty?”

“No, but if you’d like, you can join us for dinner tonight, it’ll be a private affair, just my closest advisers and you.” She leaned towards him in her chair. “It’ll be terribly boring but I’m willing to bet the foods better down here.” She joked, and a smile spread across her face. She was trying.

“I will have to make sure I’m not needed on the Supremacy. But that sounds nice.” Ben smiled under his mask. She stood, and smoothed her skirt. He stood as well, he knew at the very least that was the respectful thing to do.

“I’ll see you at dinner then, Commander.” She turned to make her exit.

“Majesty.” He bid goodbye, and he bowed his head ever so slightly. He thought she was all the way around and she hadn’t noticed. But she did.

Kylo was shown to a set of rooms to make a private transmission to the Supreme Leader. He took his mask off, and laid it at his feet, and bent at the knee as the hologram came alive.

“What news do you bring?” The beast growled at him.

“She was contacted by the pilot, she didn’t seem to know he’s pledged himself to the Rebels.” Kylo said as fast as he could, like a beaten dog preparing for the lashing.

Snoke paused. “What else, my apprentice?”

“She’s invited me to stay for her private dinner.” His voice shook when he said it, he cleared his throat and held his breath.

“Good..” The Supreme Leader croaked. “We need her to trust you. To follow you. Go to her measly dinner. We need you two wed.”

“Yes Supreme Leader.” He bowed his head, sensing an end to the conversation, he began to place his helmet back on.

“She must not know the truth about herself before she is yours.” With that, the Leader was gone, and Kylo let out a breath he didn’t know he had been holding. He began to wander around the private rooms he had been given, they were covered in colorful art. His black robes created such a contrast and he felt like he didn’t belong in a place so full of light. He didn’t feel he belonged anywhere, but at least aboard the ships, he could blend in, and look the part of the menacing commander. He walked to the edge of the room, just before the balcony. He’s sweating, and he hasn’t stepped outside. It's still early autumn on Adrora, and the sun is still burning as hot as ever. He knew their summers were short, but the heat was enough for full planet’s cycle.

He turns into the bedroom, and there’s things folded on the bed. He picks them up with gloved hands and realizes what they are. Men’s clothes. Black still, but made of much lighter fabric, the matching trousers folded neatly under. He toys with the idea, and eventually decides to change. He picks up a handwritten note that falls from the stack.

While I understand the statement, I’m afraid you’re a bit overdressed. I’ll see you at dinner. - a

He runs his hand over the writing a few times, and folds the note, hiding it in the helmet he decides to leave behind tonight. He keeps his saber clipped to his belt, and heads for the door to the hall. He runs a hand through his black hair a few times, trying to keep it tamed. Kylo stares in the mirror. He feels like Ben Solo, and he should be discouraging it.

But surrounded by so much color, he thinks maybe it’s not such a bad thing for right now.

#ben solo has my heart#poe dameron x ofc#poe dameron x oc#kylo ren x ofc#kylo ren x original character#star wars fanfiction#kylo ren#poe dameron#this is my favorite work yet#enjoy

16 notes

·

View notes