#ive been referring to myself as a court jester for Years

Text

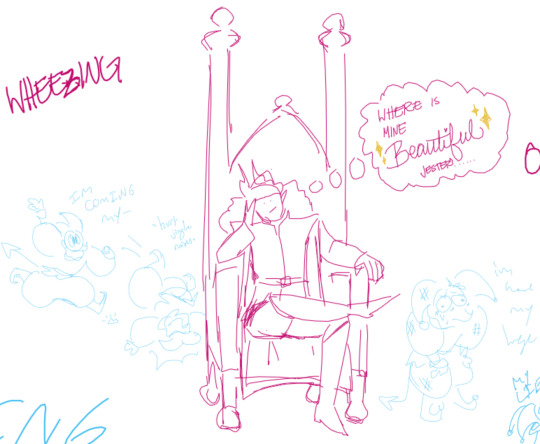

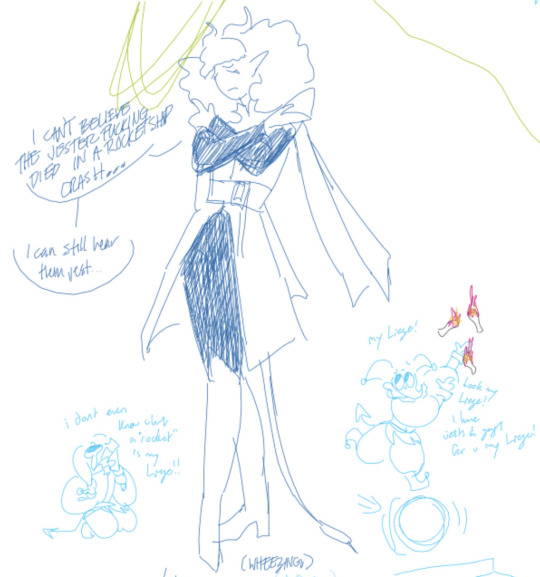

whiteboard tomfoolery with me beloved @awkwardalphajay <3 aka we roleplayed monarch/jester with our sonas for like. Four Hours

aka we made an octopus board

the octopus in question:

#THIS IS SO FUCKING LONG HELP#anyway so. yeah i cant really explain what happened#we were talking as we do and just kinda#naturally Slid into our monarch/jester personas. we were Possessed!#MY LIEGE IF YOU'RE READING THIS!!! MY BELLS JINGLE MOST MERRILY FOR THEE!#i swear to gather better jesterly material for thine enjoyment <3#scribble salad#i was born to be a jester#ive been referring to myself as a court jester for Years#i was born in the wrong era... i wouldve killed it in the throne room#jaime. jaime. thank you for indulging me this was Everything#you've had me straight Wheezing two nights in a row now <3#mwah. mwah mwah mwah mwah <3#🩷🍈🩷🍈🩷🍈🩷🍈🩷🍈🩷🍈🩷

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iain Glen in HENRY IV, part 1: in 3 hours 50 minutes, and counting...

On BBC Radio 3, Sunday April 26, 19H30 UK time (available to all on the BBC’s website if you listen to the play live)

Yesterday, in my teaser interview with @pnienor, our resident Bard expert singled out a specific scene in which the King stands out: “...the exchange with Hal in Act 3, scene 2, I think, is where you find out just how good he is at keeping his crown and why. You want Hal to emulate him after this and he does.” ... Sooooo wanting to investigate this a bit further, I went into the text which will enable Iain Glen to shine and, lo and behold, I found yet more meta-theatrical resonances to enjoy!

During Henry’s lengthy (!!) impassioned address to his son, at one point he explains how he won the admiration of his people through modesty. While the previous King pranced around like some red carpet hungry star (my image ;-), his shying away from the public eye made his rare appearances all the more glorious and commanded respect.

Reminds you of anyone?

I CANNOT wait to hear Iain Glen say (and please also note the Jorah-ish reference to banishment!):

If I had been so publicly visible, so overly familiar to people, so freely accessible, so cheap and available to the common hordes, then public opinion (which helped me get the crown) would have stayed loyal to King Richard. I would have stayed a banished man, with no reputation and no promise of success. But because I was so rarely seen in public, people were amazed by me when I did appear; they acted as if I were a comet. Men would tell their children, “That’s him!” Others would ask, “Where? Which one’s Bolingbroke?” I was more gracious than heaven; I acted so modestly that I won the allegiance of their hearts, and the shouts and salutes of their mouths. They even did so when the King himself was present.This is how I kept myself fresh and new. I was like a priest’s ceremonial vestments: rarely seen, but admired. I appeared seldomly, but marvelously, like a feast made all the more impressive by its rarity. Now, ridiculous King Richard pranced about with vapid clowns and superficial wits, quickly lit and just as quickly burnt out. He degraded himself, mingling his royal self with those skipping fools.

(...) They didn’t look with a special gaze, as they do at the sun when it shines only rarely.

**********************************************************************

Oh Ser, we do look upon you as the Sun :-) And you have indeed succeeded in keeping yourself fresh and new throughout your long and distinguished career, one which is entering its harvest season. Long live the King!

edit by @favor757

Below the dot-dot-dot, the original text of Act 3, scene 2 (I’m still not sure how much this BBC 3 production will have modernized it)

Act 3, scene 2 - London. The palace.

Enter KING HENRY IV, PRINCE HENRY, and others

KING HENRY IV

Exeunt Lords

PRINCE HENRY

So please your majesty, I would I could

Quit all offences with as clear excuse

As well as I am doubtless I can purge

Myself of many I am charged withal:

Yet such extenuation let me beg,

As, in reproof of many tales devised,

which oft the ear of greatness needs must hear,

By smiling pick-thanks and base news-mongers,

I may, for some things true, wherein my youth

Hath faulty wander'd and irregular,

Find pardon on my true submission.

KING HENRY IV

God pardon thee! yet let me wonder, Harry,

At thy affections, which do hold a wing

Quite from the flight of all thy ancestors.

Thy place in council thou hast rudely lost.

Which by thy younger brother is supplied,

And art almost an alien to the hearts

Of all the court and princes of my blood:

The hope and expectation of thy time

Is ruin'd, and the soul of every man

Prophetically doth forethink thy fall.

Had I so lavish of my presence been,

So common-hackney'd in the eyes of men,

So stale and cheap to vulgar company,

Opinion, that did help me to the crown,

Had still kept loyal to possession

And left me in reputeless banishment,

A fellow of no mark nor likelihood.

By being seldom seen, I could not stir

But like a comet I was wonder'd at;

That men would tell their children 'This is he;'

Others would say 'Where, which is Bolingbroke?'

And then I stole all courtesy from heaven,

And dress'd myself in such humility

That I did pluck allegiance from men's hearts,

Loud shouts and salutations from their mouths,

Even in the presence of the crowned king.

Thus did I keep my person fresh and new;

My presence, like a robe pontifical,

Ne'er seen but wonder'd at: and so my state,

Seldom but sumptuous, showed like a feast

And won by rareness such solemnity.

The skipping king, he ambled up and down

With shallow jesters and rash bavin wits,

Soon kindled and soon burnt; carded his state,

Mingled his royalty with capering fools,

Had his great name profaned with their scorns

And gave his countenance, against his name,

To laugh at gibing boys and stand the push

Of every beardless vain comparative,

Grew a companion to the common streets,

Enfeoff'd himself to popularity;

That, being daily swallow'd by men's eyes,

They surfeited with honey and began

To loathe the taste of sweetness, whereof a little

More than a little is by much too much.

So when he had occasion to be seen,

He was but as the cuckoo is in June,

Heard, not regarded; seen, but with such eyes

As, sick and blunted with community,

Afford no extraordinary gaze,

Such as is bent on sun-like majesty

When it shines seldom in admiring eyes;

But rather drowzed and hung their eyelids down,

Slept in his face and render'd such aspect

As cloudy men use to their adversaries,

Being with his presence glutted, gorged and full.

And in that very line, Harry, standest thou;

For thou has lost thy princely privilege

With vile participation: not an eye

But is a-weary of thy common sight,

Save mine, which hath desired to see thee more;

Which now doth that I would not have it do,

Make blind itself with foolish tenderness.

PRINCE HENRY

I shall hereafter, my thrice gracious lord,

Be more myself.

KING HENRY IV

For all the world

As thou art to this hour was Richard then

When I from France set foot at Ravenspurgh,

And even as I was then is Percy now.

Now, by my sceptre and my soul to boot,

He hath more worthy interest to the state

Than thou the shadow of succession;

For of no right, nor colour like to right,

He doth fill fields with harness in the realm,

Turns head against the lion's armed jaws,

And, being no more in debt to years than thou,

Leads ancient lords and reverend bishops on

To bloody battles and to bruising arms.

What never-dying honour hath he got

Against renowned Douglas! whose high deeds,

Whose hot incursions and great name in arms

Holds from all soldiers chief majority

And military title capital

Through all the kingdoms that acknowledge Christ:

Thrice hath this Hotspur, Mars in swathling clothes,

This infant warrior, in his enterprises

Discomfited great Douglas, ta'en him once,

Enlarged him and made a friend of him,

To fill the mouth of deep defiance up

And shake the peace and safety of our throne.

And what say you to this? Percy, Northumberland,

The Archbishop's grace of York, Douglas, Mortimer,

Capitulate against us and are up.

But wherefore do I tell these news to thee?

Why, Harry, do I tell thee of my foes,

Which art my near'st and dearest enemy?

Thou that art like enough, through vassal fear,

Base inclination and the start of spleen

To fight against me under Percy's pay,

To dog his heels and curtsy at his frowns,

To show how much thou art degenerate.

PRINCE HENRY

Do not think so; you shall not find it so:

And God forgive them that so much have sway'd

Your majesty's good thoughts away from me!

I will redeem all this on Percy's head

And in the closing of some glorious day

Be bold to tell you that I am your son;

When I will wear a garment all of blood

And stain my favours in a bloody mask,

Which, wash'd away, shall scour my shame with it:

And that shall be the day, whene'er it lights,

That this same child of honour and renown,

This gallant Hotspur, this all-praised knight,

And your unthought-of Harry chance to meet.

For every honour sitting on his helm,

Would they were multitudes, and on my head

My shames redoubled! for the time will come,

That I shall make this northern youth exchange

His glorious deeds for my indignities.

Percy is but my factor, good my lord,

To engross up glorious deeds on my behalf;

And I will call him to so strict account,

That he shall render every glory up,

Yea, even the slightest worship of his time,

Or I will tear the reckoning from his heart.

This, in the name of God, I promise here:

The which if He be pleased I shall perform,

I do beseech your majesty may salve

The long-grown wounds of my intemperance:

If not, the end of life cancels all bands;

And I will die a hundred thousand deaths

Ere break the smallest parcel of this vow.

KING HENRY IV

A hundred thousand rebels die in this:

Thou shalt have charge and sovereign trust herein.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Better to be Jews than Christians

Better to be Jews than Christians

Anton de Montoro and the Spanish Converts

By Jeffrey Gorsky

(adapted from a chapter in my history: Jewish Blood, the Tragedy of the Iberian Jews.)

The 15th Century Castilian Anton de Montoro was the most representative poet of the Spanish "conversos". A convert to Catholicism, he flaunted his Jewish heritage. He dramatized the plight of his fellow converts, victims of discrimination and violent persecution. He wrote about something unique in Jewish history—a community of thousands brought into Catholicism through force or compulsion, trying to fit into their new Christian world.

The conversions came at the end of one of the most successful Jewish periods in human history. For centuries, during the "convivencia", Jews prospered from unprecedented, if limited, tolerance from Muslim and Christian rulers. The Jews exploited new opportunities for power, riches, and cultural and scientific encounters. Their success led them to call their land Sepharad, a name from the book of Obadiah that implied that Spanish Jews were the successors to the Jews of Israel.

This world ended in 1391. A rogue priest named Ferran Martinez incited mobs to riot throughout Spain with the slogan "Convert or die". When the violence ended, further State and Church repression followed. After 20 years of repression, a third to half of the Spanish Jews had converted.

These "conversos" quickly achieved enormous success. They obtained high public office, rose to the top of the Church hierarchy, and married into the aristocracy. But their success bred resentment. During 60 years of civil war and instability, they became handy scapegoats. They inherited the hatred and resentment traditionally directed against Jews. This led to violent anti-Convert riots, mostly centered in Southern Spain.

By the reign of Enrique IV (half-brother to his successor, Queen Isabella), most conversos had been Christian for two generations or more. This new generation had much less solidarity as conversos than their previously converted forefathers. The instinct of Jews and early conversos to side with the King for protection led the first generation to side almost unanimously with King Juan II and his principal minister Alvaro de Luna—but Luna sold them out. When Juan's son Enrique inherited both the throne and civil unrest, conversos were on all sides of the new civil wars: some stuck by the King, some sided with his brother Prince Alfonso, while others supported the untrustworthy minister Don Pacheco even after he showed he could be as treasonous to conversos as he was to the King.

The new political loyalties of the conversos reflected their assimilation and adoption of Old Christian manners. But while the conversos rejected Judaism (whether through free-will or compulsion) they were still distrusted and discriminated against by Old Christians. This blocked full assimilation. Conversos developed their own perspective and customs. This soon became an important force in Spanish art and culture.

The converso perspective first erupted through humor. The court jester, or truhan, became a feature of the Court in the 15th Century. The jesters were largely or wholly conversos. This may have been in part due to the Jewish cultural acceptance of humor. It also reflected the conversos marginal status—it was easier for Old Christians to make fun of these former Jews, and they in turn could look more skeptically and satirically at Castilian society.

A school of poetry developed during this period, with the poets called the Cancieneros, or songsters. While these poets wrote in a wide variety of styles, much of their poetry was burlesque, jester poetry written to entertain and gain the patronage of the royal court and grandees.

Many if not most of these poets were conversos. Among them, Anton de Montoro stood out as the cancionero poet who most openly admitted to his Jewish heritage. He dramatized the plight of the converso, and protested the killings and discrimination conversos suffered in Castile.

Born a Jew around 1404 in or near Cordoba, Montoro probably converted around the time of the anti-Jewish legislation of 1414. His Jewish name was Saul, and his mother remained Jewish.

He became known as the "Ropero", or clothes peddler. Trade had a low status in Castilian society, and this trade was particularly low. A tailor could service the aristocracy, and anyone with money would have clothes made-to-order. A seller of used or ready made clothes only serviced those too poor to buy fashionable wear.

He became known as a poet late in life. His first known poems date from the 1440s, when he obtained the patronage of the dominant aristocrat of Cordoba. He became one of the most successful poets of his day, engaging in poetry duels or correspondence with other well-known poets, and leaving a reasonably substantial estate.

Montoro may have stressed his low class and Jewish background partly as a pose. Like jesters, the comic cancioneros poked fun at themselves. Juan Baena, for example, a prominent converso poet, pointed to his physical ugliness and short-stature.1 Montoro's low-class occupation and Jewish background allowed, like a physical defect, for self-deprecating humor.

Montoro often satirized his Jewish descent. In a poem to his wife, he notes that they were well matched as conversos, and that he won the match because she was considered unworthy for any reputable Christian:

"You and I

and to have but little worth,

we had better both pervert

a single house only, and not two.

For [wishing] to enjoy a good husband

would be a waste of time for you,

and an offense to good reason;

So I, old, dirty, and meek,

will caress a pretty woman."2

As a comic poet of his era, he could be bawdy even by our standards. One of his poems is called, To the Woman Who Is All Tits and Ass (Montoro a Una Mujer Que Todo Era Tetas Y Culo)3. In Montoro to the Woman Who Called Him Jew, his response to what a woman meant as an insult is to refer to her as a sodomite, implying that the mouth that sent out that insult was used to perform oral sex.4

In several poems, without entirely abandoning the satiric voice, he bitterly protested the mistreatment of the conversos. After the attacks on the conversos in Carmona, he addressed King Enrique IV: "What death can you impose on me/That I have not already suffered?"5

The massacre of conversos in his hometown of Cordoba elicited a lengthy and complicated poem to Alonso de Aguilar, the aristocrat who after befriending the conversos deserted them during the attack and then allowed them to be exiled and barred from public office: "Montoro to Don Alonso de Aguilar on the Destruction of the Conversos of Cordoba". The poem begins as a fulsome panegyric to Aguilar, possibly reflecting Montoro's need to continue to live under Aguilar's protection in Cordoba. Only after eight verses of praising Aguilar does Montoro turn to the massacre, noting that after this disaster "it would serve the conversos better to be Jews than Christians."6

By verse 19, he praises the Grandee, and abjectly begs mercy for the conversos: "We want to give you tributes, be your slaves and serve you, we are impoverished, cuckolded, faggots, deceived, open to any humiliation only to survive." In the next verse, Motoro describes himself as "wretched, the first to wear the livery of the blacksmith" (the man who started the anti-converso riots). He pleads for the grandee's mercy, while he remains "starving, naked, impoverished, cuckold, and ailing."7

It has been suggested that this poem is an ironic attack on his former patron. Yet there is no apparent irony in the poem. The main attitude seems to be helpless despair in wake of the destruction of his fellow converts.

His best-known depiction of the plight of the conversos comes in his poem dedicated to Queen Isabel:

"O sad, bitter clothes-peddler [ropero]

who does not feel your sorrow!

Here you are, seventy years of age,

and have always said [to the Virgin]:

"you remained immaculate,"

and have never sworn [directly] by the Creator.

I recite the credo, I worship

pots full of greasy pork,

I eat bacon half-cooked,

listen to Mass, cross myself

while touching holy waters--

and never could I kill

these traces of the confeso.

With my knees bent

and in great devotion

in days set for holiness

I pray, rosary in hand,

reciting the beads of the Passion,

adoring the God-and-Man

as my highest Lord,"8

Yet for all the Christian things I do

I'm still called that old faggot Jew.

The epitath at the end of the verse, "puto Judio" is a generic insult, not an imputation of homosexuality—it is the worst insult in the language: "behind the sodomite, bearer of pestilence, is the outline of the converso. They are joined in the worst popular insult that could be hurled: 'faggot Jew!.'. 9 "The English translation of "puto judio" cannot fully convey the pejorative sense of this masculinization of "puta," which figures the Jewish male subject both as a whore and as the passive partner in the homosexual act. " 10

The poem ends with a chilling prediction of the soon to be established auto-da-fe: He asks Queen Isabella, if she must burn conversos, to do it at Christmastime, when the warmth of the fire will be better appreciated.

Montoro evaded the Inquisition. He died soon after writing the poem, probably before the Inquisition came into force. He showed his lack of respect for the Church by leaving it only a nominal sum in his will. His wife was not as fortunate: she was burned as a heretic before April, 1487.11

As an artist, Montoro represents both a dead-end and a harbinger. He was a dead-end because with the imposition of the Spanish Inquisition and the purity of blood laws, conversos after him could no longer proudly point to their Jewish roots. That attitude would lead to being burned to death as a heretic. Converso artists turned instead to secrecy and indirection. It is no coincidence that the two most important works by conversos, La Celestina and Lazarillo de Tormes (both classics of world literature), were both initially published anonymously.

He was a harbinger in that the attitudes he and other cancioneros embraced: irony, irreverence, and the use of low class characters to attack the pretensions of the higher classes, would soon inspire a much more important genre. Picaresque literature came out of the cancionero tradition.12 The picaresque novel, in its turn, was to become part of the foundation of modern literature.

1

Francisco Marquez Villanueva, "Jewish 'Fools' of the Spanish Fifteenth Century",

Hispanic Review

, V. 50, No. 4 (Autumn, 1982), P. 393.

2 Yirmihayu Yovel, "Converso Dualities in the First Generation: The Cancioneros", Jewish Social Studies, V.4, N. 3 (1998), P. 4-5.

3 Montoro, Antón de. Poesía completa. Ed. Marithelma Costa. Cleveland: Cleveland State University Press, 1990., Poem No. 12

4 Ibid, poem No. 10

5 Marquez Villanueva, P. 403.

6 Montoro, Antón de. Poesía completa, P. 23

7 Ibid, P. 29-30

8 Yovel, P. 5-6

9 Barbara Weissberger "A Tierra, Puto!", in Queer Iberia, (Duke University Press, 1999), p. 294

10 Ibid, P. 316

11 Marquez Villanueva, P. 397

12 Victoriano Roncero Lopez, "Lazarillo, Guzman and Buffoon Literature", MLN 116 (2001), P. 237.

This article is adapted from a chapter in my draft history: Jewish Blood, The Tragedy of the Iberian Jews, about the Spanish Heine, Anton de Montoro, who dramatized the plight of the forced converts in 15th Century Spain.

3 notes

·

View notes