#john hooker packard

Text

Sneering at "sickly sentimentality": John Hooker Packard's advocacy for gas chambers

Going a complete different direction from my last post, I'm focusing on John Hooker Packard, my ancestor, herein called Dr. Packard, as today is the World Day Against the Death Penalty. As a warning, this article goes down a dark road, discussing death, suicide, and injury. Dr. Packard was more than a person who had a "large practice as a physician" and died from heart disease at the Hotel Chalfont, Atlantic City at age 75 in May 22, 1907, as noted in an obituary in the Philadelphia Inquirer at the time. He was well-known for his medical practice, as was his son Frederick. He was even described in the 1920 A Cyclopedia of American Medical Biography [1]:

"He was also one of the original members of the American Surgical Association…In 1886, in a paper read before the Medico-Legal Society of New York, he suggested the use of a lethal chamber for the infliction of the death penalty, death to be caused by the abstraction of oxygen from the atmosphere and the introduction of carbonic acid gas. Dr. Packard was a profoundly religious man, an Episcopalian…his belief was a vital part of his existence and colored all the important actions of his life. He had very considerable artistic ability and much of his work was illustrated with his own pencil…His culture, geniality and sense of humor endeared him to many, both contemporaries and also many of a younger generation, with all he maintained a pleasant social intercourse."

When reading that, I looked more into the anecdote about the use of a lethal chamber for the death penalty within this biography. While some repeated it without giving any more details, others excluded it entirely from their biographies. This is despite the fact that some even declare he was one of the "most prominent surgeons" of the latter 9th century and a "pioneer of modern American surgery". [2] In contrast to Volume 2 of University of Pennsylvania: Its History, Influence, Equipment and Characteristics; with Biographical Sketches and Portraits of Founders, Benefactors, Officers and Alumni stated he was president of Medico-Legal Society of New York.

At first, it did not seem that this page survived, as it is not within the National Library of Medicine, but after digging a little, I found the paper, which is entitled "The Mode for Inflicting the Death Penalty" and it was actually read before the society on April 1, 1878 not in 1886 as the biography had stated. At first he gives a background and talks about the "humanitarian side" of the equation, noted that many human societies have murderers of people killed. He pushes back against those who view law and order as "oppressive shackles" and claims that the death penalty is calm and dispassionate, not a "physical terror". He does say that executions are public, even if they are claimed to be private, and suggests that instead of other forms of execution (he cites lynching of a Black man as an example, something which he doesn't seem to approve of), people are, instead put in an airtight room and killed by carbonic oxide. He defends this method of killing as painless and not causing suffering. He then sneers at those opposed to such capital punishment, writing:

"Between the sickly sentimentality which wold spare merciless murderers and the brutal ferocity which would exult over their dying agonies, there seems to be a just and wise medium, where the law can take its stand…and yet inflicting no needless torture on the unhappy criminal"

If I understand this correctly, Dr. Packard is saying that death by carbonic oxide does not cause needless suffering and that the form of death he is proposing is more humane. These deaths would also be private.

Carbonic oxide is another name for carbon monoxide (CO). During the Texas power crisis last year, people were poisoned by turning on cars in garages, bringing grills into houses, etc. in an attempt to stay warm. Are those deaths humane? The Consumer Product Safety Commission describes CO as a "deadly, colorless, odorless, poisonous gas"which is undetectable to human sense, and notes that initial symptoms of low to moderate CO poisoning are similar to the flu but without the fever, such as headaches, fatigue, shortness of breath, nausea, and dizziness. What Dr. Packard is talking about falls more into the higher level of CO poisoning which has more severe symptoms, like mental confusion, vomiting, loss of muscular coordination, loss of consciousness, and untimely death. The page goes onto say that those with higher level exposures to CO can "rapidly become mentally confused...[and] lose muscle control without having first experienced milder symptoms". This is echoed by New Health Advisor which states that those who attempt to kill themselves by poisoning themselves with CO suffer a lot, causing their head to get clouded, vomiting and fainting, and are likely to fail.

CO can come from exhaust of internal combustion engines or combustion of various other fuels like wood, coal, charcoal, trash, and so on. It is even more problematic that Dr. Packard is supporting this considering that the Nazis used CO for genocide during the Holocaust, either with gas vans, in so-called euthanasia programs, or in infamous gas chambers. Specifically, it was used to murder over 700,000 people, as gas was fed into tubes at medical hospitals and concentration camps, using exhaust fumes from engines of tanks and other CO. [3] He wants there to be gas chambers to kill murderers. Others who support CO as a way to execute people include an aide of the notorious Jack Kevorkian who claimed it is "extremely painless" and replace lethal injections. It is much more painful than many think it is and is not environmentally friendly, even though it may be a quick death. [4]

Lethal gas chamber at San Quentin State Prison in 1938. Luckily, it is no longer operational.

At the time that Dr. Packard presented that article, there had been the extermination of stray dogs by a CO gas chamber a few years before (he references it in the article) in 1874. It would be followed, in 1884, by a carbon monoxide gas chamber in a slaughterhouse as described in Scientific American. There have been, more recently, CO gas chambers used to kill prisoners at San Quentin State Prison in California, [5] and only closed after public pressure. Currently, the last person to die in the U.S. with a gas chamber was Walter LaGrand, who the state of Arizona executed in 1999. Gas chambers have been rarely used since 1976 for executions.

If Dr. Packard wrote a similar article today, it would likely receive much more criticism. A September 2021 poll said that 54% of U.S. adults favor the death penalty, a five decade low. Additionally, of the over 8,700 executions between 1890 and 2010 carried out by gas chamber, 5.4% were botched, making the "gas chamber the second most unreliable execution method...used in that period". [6] It was, as I noted earlier, prominently used by General Rochambeau against Haitians during the Haitian Revolution, the Nazis, and the U.S., [7] It involves use of CO or hydrogen cyanide.

More recently, in the 18th and 19th century, scientists "suggested a therapeutic application of CO" and it is even seen as a "viable pharmaceutical candidate". Hopefully, Dr. Packard would not be seen as a person of "culture, geniality and sense of humor" for favoring gas chambers, said to be one of the cruelest methods of death, since a majority of Americans believe that life imprisonment with no possibility of parole is a "better punishment for murder than the death penalty is."

Notes

[1] Howard Atwood Kelly, A Cyclopedia of American Medical Biography: Comprising the Lives of Eminent Deceased Physicians and Surgeons from 1610 to 1910, Vol. 1 (W.B. Saunders Company, 1920), pp. 873-874. His son, Frederick is described on pages 872-873 in a biography by Francis R. Packard. The latter also wrote his biography. Francis is Dr. Packard's son.

[2] See page lviii of the Transactions of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. In contrast, the Encyclopedia of Civil War Biography which has a biography on him, Charles Packard (Lancaster, Massachusetts, Massachusetts Abolition Society, Manager, 1842-44), Alpheus Spring Packard, Jasper Packard, and Theodore Packard (Shelburn, Massachusetts, Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, Vice-President, 1836-40), does not mention this. The last sentence is quoting from the biography of him on the American Civil War Medicine & Surgical Antiques website.

[3] This is said to be stated on page 323 of A History of Modern Germany 1800 - 2000. More specifically it is described in horrifying detail on page 156 of Dictionary of Genocide [2 volumes] by Paul R. Bartrop and Samuel Totten.

[4] "Jack Kevorkian's Aide Pushed Carbon Monoxide for Executions," NBC News, Jun. 2, 2014. Also see "Why not use carbon monoxide for executions?" (Quora), "Why do states not use carbon monoxide for legal executions?" (Quora), "Is carbon monoxide poisoning the fastest and least painful way to die?" (Quora), "Why is carbon monoxide poisoning the easiest and least painful way to die?" (Quora), "What is it like to get carbon monoxide poisoning?" (Quora), "Why do people not know they are being poisoned by carbon monoxide? What would it feel like? Surely they notice they start to feel different?" (Quora), "Why Don't We Use Carbon Monoxide for Capital Punishment?" (Reddit), "Recommendation: A Death Penalty with a Carbon Monoxide Gas Chamber".

[5] The prison's official site says "The state’s only gas chamber and death row for all male condemned inmates are located at San Quentin."

[6] Austin Sarat, "Arizona’s Horrifying Plan to Bring Back the Gas Chamber." Slate, Jun. 4, 2021. Also see "Firing Squad to Gas Chamber: How Long Do Executions Take?" in NBC News, "Gas chamber 'ready' for Thanos execution but prison officials say little else" in Baltimore Sun, The Last Gasp: The rise and fall of the American gas chamber, and Gruesome Spectacles: Botched Executions and America's Death Penalty.

[7] It was also claimed to be used in Lithuania (before Soviet occupation in 1940), North Korea, and the Soviet Union. However, for North Korea, claims are reliant on defectors and claimed genuine documents, while for the Soviet Union it relies upon somewhat questionable Russian sources.

Note: This was originally posted on Oct. 10, 2022 on the main Packed with Packards WordPress blog (it can also be found on the Wayback Machine here). My research is still ongoing, so some conclusions in this piece may change in the future.

© 2022 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#john hooker packard#packards#gas chambers#genealogy#lineage#family history#death penalty#capital punishment#ancestry#atlantic city#19th century#carbon monoxide

0 notes

Text

Doctor John H. Packard, his Irish servants, and generational wealth

Photos from page 570 of Physicians and Surgeons of America, page 353 of University of Pennsylvania: Its History, Influence, Equipment and Characteristics; with Biographical Sketches and Portraits of Founders, Benefactors, Officers and Alumni, Volume 2

In January 2021, I wrote about my ancestor, John Hooker Packard (my fourth cousin five times removed), noting that he has a personal estate of $5,000, arguing it had an inflated worth of $161,400, according to Measuring Worth, "putting him in the top 10% (or even higher) today", relying on calculations from CNN Money. I further noted that he became as successful as he did in his "respected profession" (a doctor) by "standing on the backs of others". In light of my recent two posts about Captain Samuel Packard and my 9th great-grandfather Samuel Packard, I decided to reassess my calculations and come to another determination in this post, and do a deeper dive into my ancestor. This goes a different direction than my post about how Dr. Packard favored gas chambers as a method to kill prisoners, focusing on Packard's wealth.

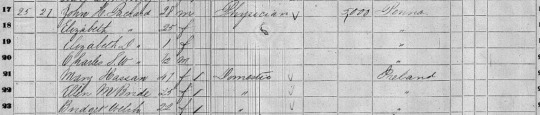

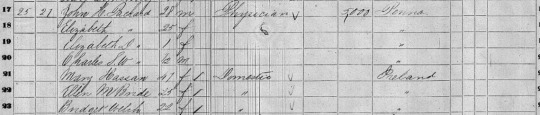

As I noted in my January 2021 post, he had at least three servants working for him (Mary Hassan, Bridget Welsh, and Ellen McBride) in 1860, and a prominent physician to say the least from my first post about him. While I could focus on his role in the U.S. Navy during the Civil War, his "radical cure" for hernia, amputation of a hip-joint, surgeons of the 19th century, oblique inguinal hernia, and urethral fistula. Similarly, there's the Report of a committee of the associate medical members of the Sanitary Commission on the subject of the treatment of fractures in military surgery with Dr. Packard as chairman, his lectures on inflammation, or anything else. [1]

This "eminent Philadelphia surgeon" was more than a person who advocated for ether to anesthesia for "brief, painful procedures" and for training of nurses. He also published a 1863 manual on minor surgery which includes methods for dulling pain and bandages, 1870 handbook on operative surgery, a 1880 book about how people can benefit from sea-air and sea-bathing, and many others. [2]

With that, let me move back to Doctor Packard and his wealth. The 1860 census which listed the three Irish servants living in his household lists a $5,000 personal estate:

1860 census document that lists three Irish servants in the Packard household

The relative value of this $5,000 dollars is best expressed as real value or real wealth, which measures the purchasing power of income or wealth by its ability to buy goods and services. That comes to $168,000.00 in 2021 values. This is not far above the median household wealth in 2021 in the U.S. is $140,800, according to the Census Bureau. It is assumed that this wealth was partially or completely passed to the children he had with Elizabeth Wood (1835-1897):

Elizabeth Dwight (1859-1915)

Charles Stuart Wood (1860-1937)

Frederick Adolphus (1862-1902)

John Hooker (1865-1947)

Francis Randolph (1870-1950)

George Randolph (1873-1936)

Elizabeth was the daughter of two Quakers, Charles S. Wood and Juliana Fitz Randolph. At age 22, she married Dr. Packard in June 1857 at Church of the Epiphany, and was likely living in Manayunk Upper Ward, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where she was living in 1850. By 1860 she was living in Philadelphia Ward 8 with the three aforementioned servants, Dr. Packard, her son Elizabeth D., and Charles S.W. [3]

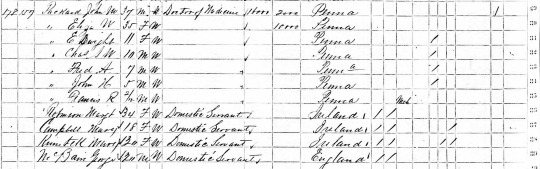

By 1870, Dr. Packard had a real estate of $106,000 and personal estate of $2,000. His wife even had a personal estate of $10,000! There were their five children (Elizabeth D., Charles S.W., Fred H., John H., and Francis R.) and four servants. Three of these servants (Margaret Robinson, Mary Campbell, and Mary Runistell?) and one in England (George McBann). That says a lot about his wealth and it is interesting that Elizabeth has that much wealth as well. That connects to what Claire Cushman writes about in the first chapter of Supreme Court Decisions and Women's Rights: under coverture rules, implemented under an attitude known as "romantic paternalism", a woman could not make contracts, write wills, sue or be sued, or own property, as that all belonged to the husband. However, there were married women's property laws beginning to be passed in the mid-19th century, increasing the rights of married women to control their own property, but limitations remained in place. Pennsylvania passed a law similar to New York in 1845 which increased married women's property rights. [4]

1870 census listing for the Packard household in Philadelphia Ward 8 District 23, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania [5] Four servants are listed in this household, one more than in 1870.

By 1880, Dr. Packard was still listed as a physician, while his wife Elizabeth was said to be keeping house. Their daughter Elizabeth was at home, Charles S.W. was a clerk, Frederick A. was at Pennsylvania University, John H., Frank R., and George R. were at school. They were still living at 1931 Spruce Street. [6] When Dr. Packard's wife, Elizabeth, died in March 11, 1897 in Devon, Pennsylvania, her estate was said to include personal property of $10,000 and $28,000 in real estate in Chester County, Pennsylvania, as noted in a petition by her sons Frederick and Charles S.W. not long after her death. Other documents in her probate include her last will and testament on in which she left Dr. Packard "all her money in stocks, bonds, mortgages, real estate", including granted her property in Devon, along with any other personal or household property. After her death, her children renounced their right to be administrators of her estate, since she had appointed Frederick and Charles S.W. as her executors on September 20, 1896. [7] Here is the text of her last will and testament in July 1892:

I leave my property in Devon, including 13 acres, house, stable gardener's cottage, and everything belonging to the place my dear husband John Hooker Packard. He is to do as he chooses with the property, sell or rent it, and after paying off all the debts, if he sells it, to invest the principal as he sees fit and have entire control of the interest during his life time and at his death the children shall divide the some. I leave him also, that is my husband (John Hooker Packard) for his life, all the money invested in stocks, bonds, mortgages, real estate, or any other way invested that I received from my mother's estate after her death. The interest to be paid to him as long as he lives and after his death to be given to my children principal and interest share and share alike. I leave him anything that he wishes for his own use, of my household and personal property and after he takes what he wishes. I leave my son Francis Randolph Packard all that he wishes, the residence to be divided among the rest of my children. My books I leave to my husband. I wish the sum of $2,000 to be taken at once from any principal and be divided equal by between my husband John H. Packard and my son Francis R. Packard. Any money coming to me from Aunt Hannah Randolph's estate I leave to my husband John H. Packard, the same to be invested by him and for him to use the interest therefore during his life and at his death the principle to return to my children, share and share alike. [8]

Only five years after Elizabeth's death, her son, Frederick Adolphus, another accomplished doctor, would die of typhoid fever in Philadelphia on November 1, 1902, at age 40. While he married a woman named Katharine Paul Shippen on June 1, 1893 in Philadelphia, they did not have children. Unfortunately, I can't find them in the 1900 census. It also does not seem he wrote a will. So, any property he held at his death is not known. [9] However, there are indications that the wealth of Elizabeth passed on. When Dr. Packard died in 1907, it did not seem he had a probate, although he likely had substantial funds when he died in a hotel in Atlantic City. In contrast, when Elizabeth Dwight died in 1915, The Wilkes-Barre Record stated on April 7 that she gifted $500 to her brother Francis R. and had a personal estate of $40,000. In something that definitely raised eyebrows for me, the remainder of her estate was given to her friend Lucy Huston Sturdevant. The latter lived at the Hotel Sterling, which happens to be a place once managed by one of my ancestors, Robert Mills, the namesake for one of my ancestors, Stanley Sterling Mills.

Lucy was well-healed, born to a prominent family, daughter of General Ebenezer Warren Sturdevant and Lucy Huston. Her obituary in 1940 described her as a member of one of the oldest families in Wilkes-Barre, insisting that her home was in Wilkes-Barre rather than anywhere else. As it turns out, Elizabeth and Lucy were more than friends. [10] The 1900 census lists Elizabeth as the partner of Lucy, with a South Carolinian cook named Lena Brooks and a South Carolinian maid named Martha Mook living in the same household in Buncombe, North Carolina:

Elizabeth and Lucy living together in the 1900 census [11]

Although I can't find records of either one in the 1910 census, it is significant that Lucy was the executor of Elizabeth's estate. Elizabeth seems to have a bit of a high-class about herself as well, hosting tea parties with her sister, going to Nantucket, while her death certificate says she was single, just like Lucy's. According to a February 1883 passport application, Lucy was 5 foot 6 inches, had blue eyes, light hair, and fair complexion. [12] Unlike Elizabeth, Lucy was known for her short stories and articles. In 1909, only a few years before Elizabeth's death, she published a short story in Atlantic Monthly entitled "A North-West End". Then, in 1915, she published a story within in the Best Short Stories of 1915. A search of her name pulls up many other stories, either about an untrained nurse, the waterfront, flags, schools, Quaker teachers, mainly in Atlantic Monthly, now known as The Atlantic. [13]

As the internet saying goes, they're gay, good for them. I had somewhat predicted I would focus on topics like this, including a question from Christine E. Sleeter in Genealogy journal in June 2020, in a January 2021 post: "How might a family historian tease out clues of LGBTQ family members in the past?" I would be more than happy to write more about Elizabeth and Lucy in the future, and do more of a deep dive. Lucy and Elizabeth seems to have a committed relationship, a union that wasn't called marriage, but falls into the labels of "life partnerships”, “romantic friendships”, “Boston marriages” or something else entirely. Some have noted that the use of “partner” as a relationship designation in 20th-century census records is something that "might identify LGBTQ relationships", even though it is not, on its own, a "completely reliable means of identifying same-sex couples in the census" although has been used by enumerators.

Moving on from this topic, and toward the conclusion of this post, some children of Elizabeth and Doctor Packard had home values in the tens of thousands. In 1930, the home of George R. and his wife Elizabeth Waln Wistar Brown was worth $50,000. The same was the case for Francis Randolph, who was living with his wife Margaret Harshman, with a home valued the same. This differed from Charles S.W. who rented a house the same year, only worth $975 dollars. Similarly, John H. also rented a house, only worth $500 dollars. Charles and John were both wage/salary workers. [14]

In sum, you could say there was some generational wealth, i.e. any assets families pass down to their children or grandchildren, whether cash, investment funds, stocks and bonds, properties or companies, but it didn't pass to all of the children of Elizabeth and Doctor Packard, only some of them.

Notes

[1] See "On a modification of the "invagination" method of operating for the radical cure of hernia" (1895?), "On amputation at the hip-joint" (1865?), "On some of the surgeons of the last century" (1888?), "On the anatomy of oblique inguinal hernia, with special reference to the operation for its radical cure, and a description of a modified procedure for this purpose" (1895?), "Traumatic separation of the lower epiphysis of the femur" (1890?), and "Urethral fistula, treated by means of the elastic ligature" (1877?). Also see "Minutes of transcriptions and business; Sept. 29, 1857 to Apr. 14, 1887, 1857-1887" (1857, mentioned), "The present state of microscopical science, medically considered" (1859), "Sea-air and sea-bathing" (1880), "A hand-book of operative surgery" (1870), "Records, 1846-1919" (mentioned), "John Fries Frazer papers, 1834-1871" (mentioned), and "Records, 1855-1909" (mentioned).

[2] See "John H. Packard’s Primary Ether Anesthesia" (2001 article), "Training of nurses for the sick ; Social Science Association of Philadelphia ; read before the Association January 20, 1876" (his speech), A manual of minor surgery (1863), A Hand-book of Operative Surgery (1870), Sea Air and Sea Bathing (1880). Others are listed here.

[3] "Pennsylvania and New Jersey, U.S., Church and Town Records, 1669-2013" via Historical Society of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Historic Pennsylvania Church and Town Records; Reel: 231, page 385 of 573; "1850 United States Federal Census", Year: 1850; Census Place: Manayunk Upper Ward, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Roll: 808; Page: 111a, Seventh Census of the United States, 1850; (National Archives Microfilm Publication M432, 1009 rolls); Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29; National Archives, Washington, D.C.; "1860 United States Federal Census", Year: 1860; Census Place: Philadelphia Ward 8, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Roll: M653_1158; Page: 6; Family History Library Film: 805158, 1860 U.S. census, population schedule. NARA microfilm publication M653, 1,438 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d. Page 723 of U.S., Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, Vol I–VI, 1607-1943, specifically Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy Vol. II, lists Elizabeth as a daughter of Charles S. and Juliana. Additionally, page 404 of The descendants of Rev Thomas Hooker, Hartford, Connecticut, 1586-1908 notes her as daughter of Charles Stuart and Juliana (Fitz Randolph) Wood and says she was born May 2, 1835 in Philadelphia.

[4] "Romantic Paternalism" in Supreme Court Decisions and Women's Rights: Milestones to Equality (ed. Claire Cushman, Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 2001), 1-2. While it is not directly stated, it is implied that Cushman wrote this section of the chapter. I originally got this book in college when I took a women in the law class. Definitely a valuable resource which I never knew I needed. The Married Women's Property Acts in the United States Wikipedia page is actually a good resource, especially citing many articles in the sources section if you wish to dive deeper into this subject.

[5] "1870 United States Federal Census", Year: 1870; Census Place: Philadelphia Ward 8 District 23, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Roll: M593_1393; Page: 119B, 1870 U.S. census, population schedules. NARA microfilm publication M593, 1,761 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.Minnesota census schedules for 1870. NARA microfilm publication T132, 13 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.

[6] "1880 United States Federal Census", Year: 1880; Census Place: Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Roll: 1170; Page: 206C; Enumeration District: 129, Tenth Census of the United States, 1880. (NARA microfilm publication T9, 1,454 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[7] "Pennsylvania, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1683-1993", Pennsylvania Probate Record; Probate Place: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Notes: Wills, No 568-593, 1897, Pennsylvania County, District and Probate Courts, Pages 199 to 216. The last will and testament is on pages 202 to 206.

[8] This document is very hard to follow, so I may have missed something, but this is pretty accurate, I believe. The whole text of the last will and testament is available as a downloadable PDF. The entire will and probate in its original form and order, of all the pages, is available in a PDF here.

[9] For a profile of Frederick see pages 872-873 of Howard Atwood Kelly, A Cyclopedia of American Medical Biography: Comprising the Lives of Eminent Deceased Physicians and Surgeons from 1610 to 1910, Vol. 1 (W.B. Saunders Company, 1920). The biography of him is written by his brother, Francis R. Packard. He is also listed on page 367 of Biographical catalogue of the matriculates of the college: together with lists of the members of the college faculty ... of University of Pennsylvania within U.S., College Student Lists, 1763-1924. Katherine and Frederick having no children is confirmed by the 1910 census (Year: 1910; Census Place: Philadelphia Ward 7, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Roll: T624_1389; Page: 3B; Enumeration District: 0108; FHL microfilm: 1375402, Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910 (NARA microfilm publication T624, 1,178 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C.) which lists Katherine as widowed and notes that she has zero children. Their marriage is noted in page 245 of Pennsylvania and New Jersey, U.S., Church and Town Records, 1669-2013 collection (Historical Society of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Historic Pennsylvania Church and Town Records; Reel: 232, Historic Pennsylvania Church and Town Records. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Methodist Church Records. Valley Forge, Pennsylvania: Eastern Pennsylvania United Methodist Church Commission on Archives and History.) Page 299 of Index to Wills, 1900-1924, M-S for Philadelphia within Pennsylvania, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1683-1993 (page 299 of 499) lists no entries for any Packards in 1901 or 1902.

[10] Although there is a Lucy H Sturdevant who married a man named Ziba M Faser in 25 Sep 1873, this is not her as she was born in 1860 and would have been 13 at the time of this marriage. For more on that Lucy, see Lucy A S Faser in the 1900 United States Federal Census, for example.

[11] 1900 United States Federal Census, Year: 1900; Census Place: Asheville Ward 3, Buncombe, North Carolina; Roll: 1184; Page: 14; Enumeration District: 0137; FHL microfilm: 1241184, Enumeration District: 0137; Description: Asheville City, Ward 3 (pt) beginning at the intersection of College and N Main, and thence NW with N Main to the City limits, thence south with City limits to Monford Ave, thence SE with Monford Ave to Haywood to French Broad Ave, thence S with French Broad Ave to Patton Ave, thence E with Patton Ave to Court Square, thence with N Main to the beginning; Includes all of Election Precinct 5, United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1900. T623, 1854 rolls.

[12] "U.S., Passport Applications, 1795-1925 for Lucy H Sturdevant", Passport Applications, 1795-1905, 1882-1887, Roll 253 - 01 Dec 1882-28 Feb 1883, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; Roll #: 253; Volume #: Roll 253 - 01 Dec 1882-28 Feb 1883, Volume: Roll 253 - 01 Dec 1882-28 Feb 1883, Selected Passports. National Archives, Washington, D.C.; "Lucy Huston Sturdevant" in the Pennsylvania, U.S., Death Certificates, 1906-1968, Pennsylvania Historic and Museum Commission; Harrisburg, PA; Pennsylvania (State). Death Certificates, 1906-1968; Certificate Number Range: 057301-060300, certificate number 58216, Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1968. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Her death certificate says she died of nephritis. Also see "1884 Dec 18 Elizabeth D Packard and Charles Packard Wife announce 5 o'clock tea on Dec 31" clipping from The Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 18 Dec 1884, Page 3, "1915 Apr 1 Elizabeth D Packard Died March 31, 1915 of 61 West Ross Wilkes-Barre" clipping from The Times Leader, Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, 01 Apr 1915, Page 24; "Obituary for Elizabeth B. PACKARD" clipping from Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, the Evening News, Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, 02 Apr 1915, Page 3, "1911 May 14 Elizabeth D Packard to Nantucket for the summer" clipping from The Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 14 May 1911, Page 27; "In her will, Elizabeth D. Packard makes Lucy Huston Sturdevant executrix of her estate" clipping from Wilkes-Barre Semi-Weekly Record, Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, 09 Apr 1915, Page 8.

[13] See "An Untrained Nurse", pages 820 to 829 in The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 107, "On the Water Front" in Atlantic Monthly, "Flag-Root" in The Atlantic, Volume 112, pages 112 to 118. There's also "The Cent School" in 1903, "Two Quaker Teachers" (also see here).

[14] 1930 United States Federal Census for George R Packard, Pennsylvania, Montgomery, Lower Merion, District 0059, Year: 1930; Census Place: Lower Merion, Montgomery, Pennsylvania; Page: 2B; Enumeration District: 0059; FHL microfilm: 2341816, District: 0059; Description: LOWER MERION TOWNSHIP (PART) BOUNDED BY (N) MATSON FORD RD., WEST CONSHOHOCKEN BOROUGH LIMITS; (E) SCHUYLKILL RIVER; (S) SPRING MILL RD.; (W) COUNTY LINE RD, United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1930. T626, 2,667 rolls; 1930 United States Federal Census for Charles S W Packard, Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Philadelphia (Districts 251-500), District 0292, Year: 1930; Census Place: Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Page: 10A; Enumeration District: 0292; FHL microfilm: 2341830, District: 0292; Description: PHILADELPHIA CITY, WARD 8 (PART), BOUNDED BY (N) LOCUST; (E) S. 13TH; (S) SPRUCE; (W) S. 21ST, United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1930. T626, 2,667 rolls; 1930 United States Federal Census for John H Packard, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Newtown, District 0105, Year: 1930; Census Place: Newtown, Delaware, Pennsylvania; Page: 15A; Enumeration District: 0105; FHL microfilm: 2341766, District: 0105; Description: NEWTOWN (NEWTON) TOWNSHIP, United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1930. T626, 2,667 rolls; 1930 United States Federal Census for Francis R Packard, Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Philadelphia (Districts 251-500), District 0280, Year: 1930; Census Place: Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Page: 31A; Enumeration District: 0280; FHL microfilm: 2341829, District: 0280; Description: PHILADELPHIA CITY, WARD 7 (PART), BOUNDED BY (N) SPRUCE; (E) S. 16TH; (S) WAVERLY; (W) S. 20TH, United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1930. T626, 2,667 rolls.

Note: This was originally posted on Dec. 12, 2022 on the main Packed with Packards WordPress blog (it can also be found on the Wayback Machine here). My research is still ongoing, so some conclusions in this piece may change in the future.

© 2022 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#packards#generational wealth#servants#family history#genealogy#wealth#genealogy research#lineage#19th century#civil war#quakers#irish#pennsylvania#marriage#chester county#typhoid#lesbians#lgbtq#nantucket#census

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blood, sweat, and tears of the Irish: The story of Mary, Ellen, and Bridget [Part 2]

Notes

[1] "United States Census, 1860", database with images, FamilySearch, 11 November 2020, John H Packard, 1860; page 6, household ID 27, NARA M653, affiliate film number 1158, GS film number 805158, digital folder number 005171158, image number 10, indexing project batch number N01813-6, record number 218.

[2] Andrew Urban (August 2009), "Irish Domestic Servants, ‘Biddy’ and Rebellion in the American Home, 1850–1900," Gender & History, 21(2): 264; accessed January 3, 2021.

[3] Thomas Low Nichols. Forty Years of American Life (London,1864), 71; quoted on "The Irish Girl and the American Letter: Irish immigrants in 19th Century America" page.

[4] Reuters Staff, "Fact check: First slaves in North American colonies were not “100 white children from Ireland”," Reuters, June 17, 2020, accessed January 3, 2021; Michael Guasco, "Indentured Servitude," Oxford Bibliographies, December 11, 2015, accessed January 3, 2021.

[5] Edward Young, "Special report on immigration...in the year 1869-'70 /," Government Publication Office, 1871, p. 216.

[6] "1924-26 Spruce Philadelphia, PA 19103," Long & Foster Real Estate, Inc., Accessed January 3, 2021. This is also asserted on Redfin. The listing describes the house as "a remarkable and rare Italian Renaissance Mansion housing 12 residential apartments in the heart of the Rittenhouse neighborhood," saying it was "built in the late 1800's at a time when fashionable architects were employed by prominent residents making their mark on the city of Philadelphia. An early elevator residence, this magnificent building has been home to prominent Philadelphia families such as Dr. John Hooker Packard, one of the most prominent American surgeons of the late 19th century." His residence there is asserted by the Journal of Sociologic Medicine, Vol. 2, p. 419 for 1889, page 1455 Boyd's Philadelphia Combined City and Business Directory in 1895, Page 183 of the Philadelphia Historical Commission's report on historic places in Philly calls it the "Earl. P. Putnam House." His obituary transcribed on Find A Grave says he died at 1926 Spruce Street.

[7] "Have You Protected Your Family For Life?," Daily Evening Bulletin, April 6, 1864, Philadelphia, Page 4, Pennsylvania Newspaper Archive, accessed January 3, 2021. Also see notices in the April 9, 1864 paper, April 14, 1864 paper, April 12, 1864 paper, April 16, 1864 paper, April 19, 1864 paper, April 26, 1864 paper, and April 28, 1864 paper.

[8] For instance, there is a "Mary Hassin" in Northern Liberties, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in Northern Liberties Ward 2, and another "Mary Hassen" in Moyamensing Township, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States.

[9] Specifically, a 50-year-old Mary Hassan and a 55-year-old Mary Hassan.

[10] "United States Census, 1870", database with images, FamilySearch, 4 January 2021, Mary Hassen, 1870; line 12, NARA M593, GS Film Number 000552919, Digital Folder Number 004278862, image 514, indexing project (batch) number N01638-5, record number 20160.

[11] "United States Census, 1870", database with images, FamilySearch, 4 January 2021), Mary Hassen, 1870; line 32, NARA M593, GS Film Number 000552919, Digital Folder Number 004278862, image 494, indexing project (batch) number N01638-5, record number 19380.

[12] "United States Census, 1880," database with images, FamilySearch,: 13 November 2020), Mary Hassen, Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; citing enumeration district ED 121, sheet 94B, NARA microfilm publication T9 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), FHL microfilm 1,255,170. Ellen Hasset and her family is mentioned on the previous page.

[14] "United States Census, 1870", database with images, FamilySearch, Ellen McBride in entry for Alfred Stille, 1870; line 16, household 964, NARA M593, GS Film Number 000552892, Digital Folder Number 004278816, image 366, indexing project (batch) number N01635-8, record number 14485.

[14] There are other measurements, but I believe this one is the most accurate to use here in this article.

[15] "The Army Medical Department Bill," The Press, Philadelphia, January 20, 1862, Page 2, accessed January 4, 2021; "New Law Books," The Press, Philadelphia, October 13, 1860, Page 3, accessed January 4, 2021; "Our Medical Schools," Daily Evening Bulletin, Philadelphia, February 6, 1866, Page 1, accessed January 4, 2021.

[16] "United States Census, 1880," database with images, FamilySearch, 13 November 2020, Rose Mc Bride in household of Richard Zeckwer, Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, British Colonial America; citing enumeration district ED 133, sheet 264C, NARA microfilm publication T9 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), FHL microfilm 1,255,170.

[17] "Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Passenger Lists Index, 1800-1906," database with images, FamilySearch, Bridget Welsh, 1857; citing ship Saranak, NARA microfilm publication M360 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 419,569. There's also a person of that name which came to New York City in 1856, but I threw that one out of contention with the assumption that she stayed in Philly.

[18] "United States Census, 1880," database with images, FamilySearch, 13 November 2020), Bridget Welsh in household of Annie E. Massey, Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, British Colonial America; citing enumeration district ED 162, sheet 94B, NARA microfilm publication T9 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), FHL microfilm 1,255,171.

[19] "United States Census, 1900," database with images, FamilySearch, 4 January 2021), Bridget Walsh in household of Emile Geyelin, Philadelphia city Ward 27, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 669, sheet 3B, family 75, NARA microfilm publication T623 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1972.); FHL microfilm 1,241,469.

Note: This was originally posted on Jan. 14, 2021 on the main Packed with Packards WordPress blog (it can also be found on the Wayback Machine here). My research is still ongoing, so some conclusions in this piece may change in the future.

© 2021-2022 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#packards#census#genealogy#genealogy research#family history#servants#irish#ireland#philly#philadelphia

0 notes

Text

Was John H. Packard really one of the best surgeons in West Philly?

Warning: This article has a graphic description of medical injury. I know its brief, but I would rather put this notice here than not, just to let people know before they read this article in its entirety. [1]

Recently, I was going through documents recently transcribed by Library of Congress volunteers. On one of the pages, a soldier writes to William Oland Bourns, a reformer, poet, editor, and clergyman who edited a periodical titled The Soldier's Friend. He had a contest from 1865-1866, as noted by LOC, where soldiers and sailors of the Union Army who lost their "right arms by disability or amputation" during the war in the past five years were "invited to submit samples of their penmanship using their left hands." Anyway, the soldier writes, on one of the pages of his August 1865 letter that he was, in late July 1862, taken by a steamer from Richmond to a West Philadelphia hospital where a man named John H. Packard cared for him. [2]

He called Packard "one of the best surgeons there," with five pieces of his bone sawed out (yikes!), along with shattered bones removed. He was not discharged from the hospital until February 1863, at which time "Dr. Packard was very proud of the operation [and] he had my photograph taken showing the arm." Its not every day where a surgeon takes a photograph of the patient they did surgery on. The soldier's name is later revealed to be Martin V.B. Keller and he lived in Lancester County, Pennsylvania.

Now what about this Packard fellow? I found a man of the same description in the as listed as living in the eighth ward of Philadelphia. The 1870 census lists him as 30-year-old man living there with his wife Elizabeth, and children: 11-year-old Bessie, 10-year-old Charles, eight-year-old Frederick, five-year-old John, and one-year-old Francis. [3] The 1860 census is more substantial, [4] showing the same children and wife, but also three Irish servants 47-year-old Mary Hassan, 25-year-old Ellen McBride, and 22-year-old Bridget Welsh. More than this, it lists him as a physician!

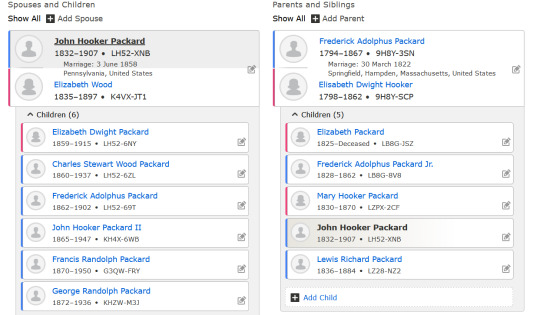

The same is the case with a 1880 census, which calls him a physician too. [5] More than that, this record, on FamilySearch, linked to the page of a man named John Hooker Packard, who would be our man! Here is a screenshot of his profile:

Going through this profile, I found an 1850 census which shows that he is the son of Frederick Adolpus Packard, a president of something, the name of which I can't make out, and Elizabeth Dwight Hooker. [6] They are living in the Spruce Ward of Philly at the time and he is listed as a doctor! Beyond this, we know from various passport applications he made in the late 1890s and early 1900s that he was born in August 15, 1832 in Pennsylvania, as he asserted over and over. [7] In those documents, he often called himself a physician. While in 1901, he calls himself a "private citizen" in the passport application, in another the following he called himself a physician. He would die of heart disease in May 1907 in Atlantic City, Atlantic County, New Jersey.

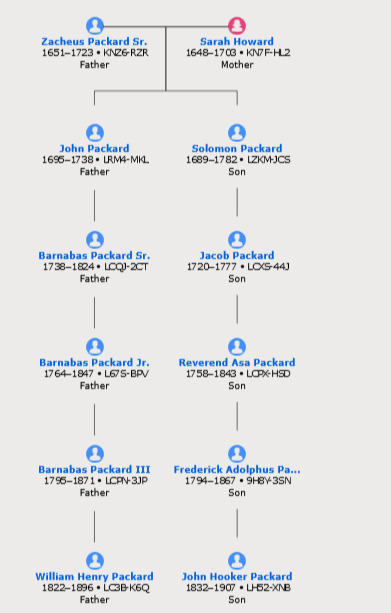

But that's not all. According to FamilySearch, John Hooker Packard is my "4th cousin five times removed." What does that mean? Well, his father, Frederick Adolphus Packard, was the son of Reverend Asa Packard. Asa, was, in turn, the son of Jacob Packard. Jacob, was the son of Solomon, and Solomon was the son of Zaccheus and Sarah, who I've written about on this blog before. This may be a bit confusing, as it was to me, so perhaps a chart of the connections would help a little more:

Before I finished doing research, I decided to do a general search for his name... and what came up? A 1863 book he wrote titled A Manual Of Minor Surgery (later adopted by the U.S. Army), which the Amazon description called a "scarce antiquarian book is a facsimile reprint...[which is] culturally important." Dr. Michael Echols & Dr. Doug Arbittier called him one of the "most prominent American surgeons of the last part of the 19th Century and a pioneer of modern American surgery," noting that he served as "acting assistant surgeon in two Union Army hospitals during the Civil War," with the latter proving Martin V.B. Keller's account as accurate. I was amazed to see an article in Anesthesiology journal in November 2001 on him by Ray J. Defalque, M.D.; Bernard Panning, M.D.; Amos J. Wright, M.L.S. In the article, they called him "an eminent Philadelphia surgeon" and how he switched from using chloroform to ether in 1864, contributing to use of anesthesia, while calling him "a pioneer of modern American surgery." Even so, they noted that in 1896, a finger of his became infected during one of his surgeries, leading him to develop septicemia, causing him to retire, and he "died from cardiorenal failure in Atlantic City in 1907." What I loved most of all about the article was not the content, but the fact that we got a photograph of him!

Some searches online find his writings in the digital collection of the U.S. National Library of Medicine, the Library of Congress, SNAC, and Harvard Library. Onward! I'm planning to write another post in the future which explores the lives of the three Irish servants, but this article is just a starting point before I get to that article. The answer to the question at the beginning of this article is "possibly," although I'm not sure anyone ever said he was the "best."

Notes

[1] This is a content warning rather than a trigger warnings, which apply to "sexual violence, oppressive language, gunshots, and representations of self-harm," along with other topics.

[2] Bourne, Wm. Oland. Wm. Oland Bourne Papers: Left-hand Penmanship contest; Soldier and sailor contributions; Series I $1,000 in prizes, awarded in; Entries 211-220. 1866. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss13375.00404/?q=packard&sp=26

[3] "United States Census, 1870", database with images, FamilySearch, 19 March 2020, John H Packard, 1870; line number 38, NARA M593, GS film number 000552920, digital folder number 004278863, image number 312, indexing project batch number N0163-6, record number 12037. Children are shown on next page.

[4] "United States Census, 1860", database with images, FamilySearch, 11 November 2020, John H Packard, 1860; page 6, household ID 27, NARA M653, affiliate film number 1158, GS film number 805158, digital folder number 005171158, image number 10, indexing project batch number N01813-6, record number 218.

[5] "United States Census, 1880," database with images, FamilySearch, 13 November 2020, John H. Packard, Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, British Colonial America; citing enumeration district ED 129, sheet 206C, NARA microfilm publication T9 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), FHL microfilm 1,255,170.

[6] "United States Census, 1850," database with images, FamilySearch, 24 December 2020, John Packard in household of Fredrick Packard, Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States; citing family 746, line 47, NARA microfilm publication M432 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), FHL microfilm 444781.

[7] "United States Passport Applications, 1795-1925," database with images, FamilySearch, 16 March 2018), John H Packard, 1893; citing Passport Application, Pennsylvania, United States, record number 2675, Passport Applications, 1795-1905., 408, NARA microfilm publications M1490 and M1372 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); "United States Passport Applications, 1795-1925," database with images, FamilySearch, 16 March 2018), John H Packard, 1897; citing Passport Application, Pennsylvania, United States, record number 5934, Passport Applications, 1795-1905., 491, NARA microfilm publications M1490 and M1372 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); "United States Passport Applications, 1795-1925," database with images, FamilySearch, 16 March 2018), John H Packard, 1901; citing Passport Application, Pennsylvania, United States, source certificate #45202, Passport Applications, 1795-1905., Roll 583, NARA microfilm publications M1490 and M1372 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); "United States Passport Applications, 1795-1925," database with images, FamilySearch, : 16 March 2018), John H Packard, 1902; citing Passport Application, Pennsylvania, United States, source certificate #56681, Passport Applications, 1795-1905., Roll 600, NARA microfilm publications M1490 and M1372 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

Note: This was originally posted on Jan. 7, 2021 on the main Packed with Packards WordPress blog (it can also be found on the Wayback Machine here). My research is still ongoing, so some conclusions in this piece may change in the future.

© 2021-2022 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#packards#genealogy#family search#family history#genealogy research#ancestry#servants#doctors#physicians#19th century#library of congress#libraries#atlantic city#pennsylvania#philly#philadelphia

0 notes