#juan matta ballesteros

Text

Golden As They Come: Chapter Seven

Pairing: Ossie Mejía x Reader

Summary: Drugs are just a necessary evil

Warning/notes: I did "research" on the CIAs involvement in cocaine trafficking during the Nicaraguan civil war and now I don't remember any of it. I put research in quotes because it sounds so formal and all I did was Google some stuff I'm not an expert ANYWAY; this chapter might be terrible; I've only seen Stechner in three episodes so he might be poorly written; I feel like he's one not to dirty his own hands but he does a little bit here; violence; blood; murder; torture; language; lots of vagueness I'm sorry; why does our reader draw the line at drugs? Idk

Rating: R

Word count: 1231

Matta Ballesteros. You heard Danilo and Sal’s voices, but the words weren’t clicking because the pieces already had. Your food tasted sour in your mouth and you nudged the plate away, getting to your feet.

“I have to make a phone call,” you said, voice so low you were surprised when Walt gave you an acknowledging nod, his brow furrowed. You were sure he was watching you as you walked away so you were careful to take your time, slow down and relax your shoulders.

You had followed Stechner around the jungles of Nicaragua like a puppy, soaking up every word that fell from his mouth, eager to learn. He quickly became your confidante, and long conversations in his office over a bottle of whatever you could find led you to believe you had become his. He gave you just enough to make you think you knew the most, when really you didn’t know anything at all. Maybe he saw something in you. Maybe you were just eager and dumb. He encouraged you to see people as tools with buttons to be pressed and levers to work; to see bodies as diagrams of pressure points, nerve centers, pain receptors. Taught you how to use pain and fear to get what you needed.

You probably would have continued to stumble through in rose colored glasses, pieces of your humanity breaking off day by day, if it hadn’t been for the boy.

“He’s one of ours,” you said after Stechner let you take a look inside the shed. He had a Contra soldier high cuffed in the center of the room, blood dripping into his eye from a cut in his forehead. You’d seen him around a few times. He seemed kind, which was no small thing. These men were not kind. If it hadn’t been for Stechner and the fact that you were CIA, this place would have swallowed you whole the moment you’d arrived. You remembered seeing the boy make a rope ball for a group of children and sneak them candy. Turns out this place would swallow him whole too.

“And he may be the reason we lost a shipment of weapons,” Stechner said. “Either he’s very lucky, or he’s a rat.”

"He’s just a kid,” you pushed, as if you weren’t one yourself, and Stechner pierced you with a calculating stare.

“I thought I could rely on you,” he said, the smallest edge of disappointment creeping into his tone.

“You can,” you rushed to assure him.

“Then get in there and do your job.”

Hours of your torture and Stechner’s circling questioning and the boy still sobbed that he didn’t know anything, he swore he didn’t know anything, he was a coward, he’d hid, please believe him. You needed to put an end to it if Stechner wouldn’t.

“He’s telling the truth,” you said, wiping your bloodied hands on a grimy towel. Stechner conceded, nodding at the floor, and your shoulders sagged in relief, expecting the worst to be over. You were wrong. Before you could react, Stechner pulled his gun and put a bullet between the boy’s eyes. Air froze in your lungs.

“He didn’t know anything!” you snapped. “If you have a leak, it’s somewhere else!”

“I tell you how to do your job, not the other way around,” he said, voice calm, matter-of-fact. “Clean this up.” Your eyes lingered on the slack body, blood dripping into a puddle on the dirt floor.

The late night talks stopped after that, and your suspicions grew, until one night you tailed a team of Contra soldiers and found yourself watching cocaine and money change hands.

You should have handled it differently, should have made sure someone else could corroborate, but a part of you wanted to believe that the man you looked up to was still there, if he ever had been at all.

“Where’s the cocaine going?” you asked. “How much do you get for it? Who supplies it?” Stechner leaned back in his chair, sighing. “Is that why you killed him? It wasn’t a shipment of weapons that was lost, was it?”

“Are you finished?” he asked.

“He was a boy,” you said, ignoring him.

“He was a soldier. And you killed him,” Stechner said, throwing you, and you stumbled in your rebuke.

“No I didn’t.” Stechner tossed a manila file down on his desk, flipping it open. You saw your picture paperclipped inside.

“I have a detailed report from that night that says that due to an error on the trainee’s part--that’s you, by the way--the subject bled out.”

“It’s your word against mine,” you fumbled.

“I think, out of the two of us, they’ll take mine,” Stechner said, closing the file. “This can go away. The drugs play a very small role in a much bigger game here. Look at them as a necessary evil. So much of this job is a necessary evil.”

“Or?”

“Or quit,” Stechner said. “Stay and suck it up, or quit. That’s how this file stays buried.”

It had been an undoing. You would keep yourself up at night reexamining everything Stechner had ever asked of you, wondering what he’d kept hidden. Wondering the level of damage you’d inflicted.

“You know I was just thinking about you.” You could hear his jaw working slowly on the other end, your call having caught him in the middle of a meal. When he spoke again, his voice was clear, cheerful. It made you sick. “I have a bag of buñuelos right here, still warm, I know you love those.”

“It was you, wasn’t it,” you said ignoring his pleasantries. “He was right in front of you and instead of doing the right thing, you did the easy thing, like always.” You heard his throat clear, and a deep sigh drifted through the receiver. You imagined him leaning back in his chair and taking the phone from where he had it cradled between shoulder and ear.

“I made a decision for the greater good,” he said finally. “But you could never see the forest for the trees. You still can’t. You were so true red white and blue and you had your rights and your wrongs and there was no room for anything in between--”

“Stop, stop it, stop talking to me like I’m a child and I don’t understand how the world works. The fact is you had a choice, you had a choice every time and you always chose yourself, you selfish piece of shit!” You slammed the receiver down, hanging on it and resting your forehead against the box. You had told yourself that wouldn’t happen, that the conversation wouldn’t spiral out of control but why else had you called Stechner if not to yell at him? The phone rang, making you jump, and you looked out at the darkening world around you. You were alone and you couldn’t help but pick it up.

“By the way,” Stechner said, not waiting to find out if it was you on the other end, “I heard through the grapevine about your recent exploits. You have a bad habit of leaving bodies in your wake.” The line went dead.

A wall came down after that. You returned to the safehouse with a hard focus, with the intent of doing your job and nothing more.

Taglist: @artemiseamoon @arellanofelixboys @thesolotomyhan @mcrmarvelloki @revolution-starter @tori-reads @acrossthesestars @spleeniexox @mesmorales @maevesdarling @unicorn-cloud

#ossie mejía x reader#narcos mexico fic#narcos mexico#ossie mejía#walt breslin#juan matta ballesteros#danilo garza#sal orozco#bill stechner

24 notes

·

View notes

Link

In recent months some have said of the migrants, “Instead of running away, they should try to change the situation in their country!” Only those unfamiliar with the Honduran situation could say such a thing. Anyone who opposes it, anyone who criticizes or tries to change it, risks death. Between 2010 and 2016, more than 120 environmental and human rights activists were killed in Honduras. Freedom of the press is also under siege, as Reporters Without Borders has documented. Honduras is one of the most dangerous Latin American countries for journalists, seventy of whom have been killed there since 2001, with more than 90 percent of those murders going unpunished. Anyone who writes has two choices: leave the country or stop writing. Exile yourself or censor yourself. Otherwise you may be sued for libel—libel suits are expensive to defend against, and even if journalists are eventually cleared, their credibility in the eyes of the public is often damaged. Or you may be jailed on false charges, or killed. And attacks on the freedom of the press come not only from criminal organizations, but also from politicians.

President Trump talks about the migrant caravan as if it were an attempted invasion. In reality, Honduras and Central America have paid an enormous price precisely because of US policies. The dire situation in Honduras right now is shaped by the drug market, and the world’s largest consumer of cocaine is the United States. As early as 1975, Honduras was being used as a staging area by the Cali Cartel, led by the Rodríguez Orejuela brothers (the powerful rivals of Pablo Escobar, the head of the Medellín Cartel). After their arrest, they told prosecutors that cocaine left Colombia by plane and landed in San Pedro Sula—the city from which the caravan originated—and from there went on to Miami.

Through the 1980s, the Colombian cartels transported their cocaine to the US mainly by boat, across the Caribbean to Florida. But when the US Drug Enforcement Administration ramped up inspections in those waters and began seizing more and more shipments, the land route to the United States from Central America through Mexico (with the help of Mexican traffickers) became a better alternative. And when the civil wars in El Salvador and Guatemala ended (in 1992 and 1996, respectively), that route was used more and more, since criminal organizations prefer to steer clear of conflict zones.

But the end of those conflicts also created another opportunity for the cartels. During the civil wars, many parents in El Salvador, in order to keep their sons from becoming either guerrillas of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) or regular army soldiers destined for slaughter, sent them to the United States. Abandoned to their fate in Los Angeles, marginalized by American society, some of these youths formed the maras, street gangs of young Central American immigrants who banded together to defend themselves from the African-American, Asian, and Mexican gangs already active there. Thus were born extremely violent, close-knit groups such as Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Mara 18 (also known as the 18th Street gang or Barrio 18), whose names came from the LA streets that were their headquarters.2

Once the Central American civil wars had ended, the US government, eager to rid itself of this problem, sent back to their native lands thousands of young men. Having left as boys, they returned as gangsters. In those ravaged countries where poverty was rampant, they saw opportunity in the drug trade, and at the same time the cartels, always looking for new muscle, found them. Meanwhile, Honduras, the one country in the region untouched by civil war, had been used not only as a smuggling hub by criminal organizations but also as a base for US efforts to supply the contras, the paramilitary group fighting the socialist government of Nicaragua. Everything, that is, passed through Honduras—both drugs and weapons—goods that often shared not only routes but also intermediaries. The story of the Honduran drug lord Juan Ramón Matta-Ballesteros is illustrative: he forged a link between the Medellín Cartel and the Guadalajara Cartel (revenue from their cocaine shipments to the United States reached $5 million a week in the 1980s), and he also worked for the US government, using his air transport company to deliver arms to the contras.

The involvement of the United States goes further. In 2008 the US government signed the Mérida Initiative with Mexico and the Central American countries, a multiyear agreement under which it pledged to cooperate in the fight against drug trafficking by providing those countries (especially Mexico) with economic support, police training, and military resources. This crackdown pushed the Mexican cartels—already under pressure from the war on drugs that Mexican president Felipe Calderón had begun in 2006—to lean increasingly on Central America and its drug gangs.

The Honduran situation worsened on June 28, 2009, when a military coup forced President Manuel Zelaya to flee to Costa Rica. Zelaya had been elected with the support of the rich conservatives of the Partido Liberal, but during his term, which began in 2006, he proved open to dialogue with minority groups and friendly to the poorest, least powerful classes. In an effort to improve his country’s economy and his people’s lives, he joined the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA), an organization conceived by former Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez to promote economic cooperation among the countries of Latin America and to counter the influence of the US over them.

But Zelaya was veering too far to the left for the Honduran oligarchy that had put him in power. The chance to oust him arose when he called for an advisory referendum on the election of a constituent assembly to rewrite the Honduran constitution with the goal of increasing participatory democracy and citizen equality. The assembly could also have removed presidential term limits, which under article 239 of the Honduran constitution could not even be proposed; this was enough for coup leaders to justify removing him, despite the fact that the referendum was merely advisory and therefore nonbinding. (Article 239 was struck down by the Honduran Supreme Court in 2015.)

After the coup, in the political instability that followed, criminal organizations ramped up their activities, taking advantage of corrupt police forces and often colluding with politicians and members of the military. On December 8, 2009, the Honduran government’s drug czar, Julián Arístides González Irías, was assassinated on his way to work: after he had dropped his daughter off at school, a car blocked the road and a motorcycle approached, one of its two riders firing an Uzi through the window of his SUV. Years later it was discovered that the murder had been ordered by high-ranking Honduran police officials and planned in one of their offices, revelations that led to a law enforcement shake-up in which over five thousand officers were dismissed on corruption charges. But in October 2018 a new and embarrassing piece was added to this already disheartening puzzle: the man who had been in charge of the “purification” of the force, National Police Commissioner Lorgio Oquelí Mejía Tinoco, was himself accused of money laundering and corruption, among other things, and is now a fugitive.

This story and many others make clear that Honduras is a de facto narco state. In 2009 Porfirio Lobo Sosa won the first presidential election after the coup; in May 2016 his son Fabio pleaded guilty to drug trafficking charges in the US, hoping for a reduced sentence. He got twenty-four years in prison. Judge Lorna Schofield said at his sentencing:

You were the son of the sitting president of Honduras, and you used your connections, your reputation in your political network to try to further corrupt connections between drug traffickers and Honduran government officials…. You facilitated strong government support for a large drug trafficking organization for multiple elements of the Honduran government, and you enriched yourself in the process.

And history may repeat itself: Juan Antonio (Tony) Hernández, a former Honduran congressman and the brother of the current president, Juan Orlando Hernández, was arrested in Miami on November 23, 2018, for his alleged ties to drug traffickers, particularly Los Cachiros, whose leader claimed in a US court to have paid him kickbacks when he was in Congress. According to the indictment, from 2004 to 2016 Hernández was involved in the trafficking through Honduras of tons of cocaine destined for the US: he accepted bribes from the traffickers, and he hired armed guards and bribed law enforcement officials to protect drug shipments and to keep quiet. Further, authorities discovered that certain cocaine labs Hernández had access to in Honduras and Colombia were producing bricks of cocaine stamped with the initials TH, which may stand for Tony Hernández. He is awaiting trial and, if convicted, faces a maximum term of life in prison.

In 2010 the United States for the first time identified Honduras as one of the major drug transit countries and since then has cooperated with Honduran authorities to combat drug trafficking. But the offensive has involved only efforts to suppress criminal organizations and has shown no real willingness to tackle, at a societal level, the problem of drug trafficking and gangs, for which the US bears a great deal of responsibility. President Trump limits himself to exploiting the effects of the tragedy: when he speaks about the caravan, he talks of “invaders,” of “stone cold criminals,” who must be coming to the US to occupy and plunder. None of this is true. But to understand, we must grasp how badly US policy has failed and how culpable and terribly complicit it is in the current situation.

Today the maras—the gangs—provide the best employment opportunities for youth in Central America. According to a 2012 report from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, the maras in El Salvador had about 20,000 members, those in Guatemala about 22,000, and those in Honduras about 12,000 (though a report that same year from USAID indicated a much higher number in Honduras). As Corrado Alvaro, an Italian writer from Calabria—a region plagued even in his day by the mafia group known as ’Ndrangheta—wrote in 1955, “When a society offers few opportunities, or none, to improve one’s station, creating fear becomes a way to rise.” Mareros, or gang members, tattoo their face and body to signal their gang membership and to openly declare their separation from civilian society, as if their gangs were military divisions operating in a sort of parallel life. Gangs control the territory and protect the trafficking of the big cartels. Businesses are subjected to shakedowns, streets become the scenes of clashes between rival gangs competing for dealing locations, and the jungle is a no-man’s land in which clandestine runways are carved for planes loaded with cocaine. Some urban areas are off-limits to ordinary citizens; a perpetual curfew reigns. The maras recruit boys—younger each year—as drug-trafficking foot soldiers; refusing to join can be fatal.

Because no one protects the populace from the abuses and threats of the gangs, people feel abandoned and in constant danger. This feeling is exacerbated by the extraordinary level of impunity in Honduras. In 2013, Attorney General Luis Alberto Rubí caused an uproar by declaring before the Honduran Congress that law enforcement had the manpower to investigate only about 20 percent of the nation’s murders, and that therefore the remaining 80 percent were certain to go unpunished. In Honduras (as in other Central American countries) being a sicario—a contract killer—is a real profession: in the morning you wake up and wait for a call asking you to commit a murder, for which you’ll be paid more than you could hope to make at any other job.

This is what people are fleeing from, this landscape that seems to offer no future but killing or being killed. Despite their varied histories, the migrants all have in common the desire—or rather the need—to escape the violence of the drug gangs and the lack of work and opportunity in their country.

It’s 2,700 miles from San Pedro Sula to Tijuana on the US–Mexico border, and with every mile the caravan grew, eventually swelling to about 10,000 people. The head of the caravan—which was several days ahead of the tail—reached the US border in mid-November. Large camps began forming in Tijuana and Mexicali, with thousands of refugees crowding into tents, waiting to be allowed to cross the border. It looked like there would be a very long wait, since—due to a new Trump administration policy—no one would be admitted to the United States prior to a hearing at an immigration court.

Faced with the prospect of remaining in that precarious limbo for weeks, perhaps months, some migrants tried to cross the border illegally, others sought asylum in Mexico, and still others gave up and turned around. According to data from the Mexican authorities reported by the Associated Press, 1,300 migrants returned to Central America; another 2,900 received humanitarian visas from Mexico and now live there legally, with the chance to look for work (which many have already found); and 2,600 were arrested by the US Border Patrol in the San Diego area alone for crossing illegally. As of mid-January, hundreds—it’s hard to know exact numbers—were still gathered at the border, hoping to enter the United States.

The caravan had many children in it, including disabled children seeking treatment in the United States. Juan Alberto Matheu, for example, traveled thousands of miles with his daughter Lesley, who has been confined to a wheelchair since having a stroke at the age of two. At every stage of the journey, he sought out washbasins to bathe her. After reaching Tijuana and spending three weeks in a refugee camp, he eventually managed—with the help of the Minority Humanitarian Foundation—to enter the US with Lesley. After four days in ICE custody, they were released, and he was finally able to take his daughter to a hospital.

Jakelin Caal Maquin, age seven, was healthy when she left Raxruhá, Guatemala, with her father, Nery Gilberto Caal Cuz. On the evening of December 6, both were arrested, along with 161 other migrants, by the US border patrol in New Mexico, after illegally crossing the border. A few hours later, while in the custody of American border agents, Jakelin began suffering from a high fever and seizures; she was taken by helicopter to a hospital, where she died the next day from septic shock, dehydration, and liver failure. She had traveled two thousand miles, crossing the Mexican desert, enduring weeks of exhaustion and hardship to reach the US, because she knew that beyond its border she could hope for something better than the future her own country offered. She died in the very place she could have begun a new life.

Jakelin was not the first migrant child to lose her life in the United States after arriving with a caravan. In May 2018 Mariee Juárez, only twenty months old, died after being held in a detention center in Dilley, Texas. Also from Guatemala, she too entered the United States illegally, crossing the Rio Grande with her mother, Yasmin. According to Yasmin, after they were arrested and put in the detention center on March 5, sharing a single room with five mothers and their own children (several of whom were already sick), Mariee developed a cough and a high fever and kept losing weight. On March 25 they were released, and Yasmin took her daughter to the hospital, where she was diagnosed with pneumonia, adenovirus, and parainfluenza. She died six weeks later.

saviano is an italian journalist whose book gamorrah was turned into the film of the same name

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Opinion: Honduras, the narco-state that illustrates U.S. contradictions

Carlos Dada is the founder and director of the news site El Faro in El Salvador.

Wherever you walk in Honduras, you are most likely in drug trafficking territory. For half a century, this country has been the Central American base for drug trafficking. Organized crime has infiltrated all institutions. If a Honduran comes across any authority — police, mayor, congressman — chances are that figure has commitments to organized crime. However, the Honduran drug trade has moved in step with the United States’ interests.

The recent New York trials against Honduran drug traffickers allow us to measure the extent of the infiltration by organized crime: military and police chiefs, politicians, businessmen, mayors and even three presidents have been linked to cocaine trafficking or accused of receiving funds from trafficking.

Lee este artículo en español

But the trials have a subplot that the scandalous testimonies of criminals have buried: the clash of agendas between the different U.S. agencies involved in Central America. The CIA, the Drug Enforcement Administration and the State Department have rarely acted in unison.

Juan Antonio “Tony” Hernández, brother of President Juan Orlando Hernández, was found guilty of smuggling 185 tons of cocaine into the United States and sentenced to life in prison. “Here, the [drug] trafficking was indeed state-sponsored,” U.S. District Judge Kevin Castel said in the sentence.

The jury concluded that Tony Hernández used the Honduran army and police for his criminal activities. From these earnings, he contributed large sums of money to the political campaigns of his brother and then-President Porfirio Lobo Sosa.

An American jury concluded that the brother of the Honduran president used the army and police for his criminal activities.

The case against him was the product of years of investigation by the DEA and the Justice Department into the criminal activities of the Hernández family. While the anti-drug agents followed the trail of the drug trafficker, the Honduran president received support from the State Department, which even endorsed his fraudulent 2017 reelection because the opposition leader, former president Manuel Zelaya, aligned himself with the Venezuelan regime. The DEA’s priority is to hunt down narcos. In Honduras, the State Department’s priority is to weaken the Bolivarian government of Venezuela, even if that means endorsing the fraudulent reelection of the head of the Hernández family.

Fabio Lobo, son of the former president Lobo, and banker Yani Rosenthal, son of one of the richest men in Honduras, were previously convicted in the same New York court. Rosenthal was found guilty of laundering money in their banks for the Los Cachiros cartel. He served a three-year prison sentence and returned to Honduras, where he’s currently the opposition’s presidential nominee.

In Honduras, one of the most violent countries in the world, 60 percent of deaths are attributed to organized crime. There are 37 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, and all 18 provinces are within the criminal groups’ grip. However, this isn’t something new. Large-scale drug trafficking in Honduras dates back to the 1970s. Ramón Matta Ballesteros, a Honduran born in poverty, took advantage of the geographical benefits of his country and established himself as a link between the Medellín Cartel (led by Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar) and the Guadalajara Cartel (led by Mexican drug lord Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo). He operated with the protection and collaboration of the Honduran Armed Forces, politicians and police, and became one of the wealthiest and most powerful Central Americans.

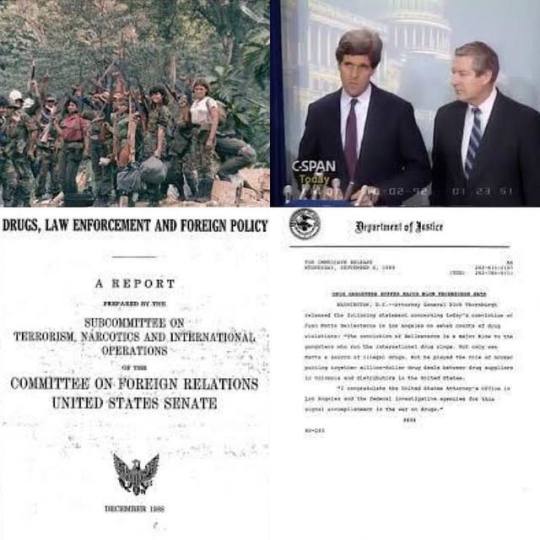

Matta set up an airline that had two clients: the Escobar cartel and the CIA. The flights went north from Colombia to the United States loaded with cocaine and emeralds and returned south to Nicaragua with weapons and ammunition for the counterrevolutionaries. Amid the Cold War, the CIA’s goal was to end the revolutionary government that the Sandinistas had installed in Nicaragua, even though the United States had already declared war on drugs.

To achieve this, the CIA needed not only Matta’s airline but the involvement of the Honduran army, which protected Matta. Years later, the Kerry committee report on support operations to the Nicaraguan Contras confirmed Matta’s involvement with the drug trafficking and the transportation of combat supplies. It also questioned the fact that DEA operations in Honduras were shut in 1983, despite evidence of military involvement and knowledge of Matta’s activities. The DEA’s anti-drug agenda collided with the anti-communist strategy of the CIA and the White House. But the anti-narcotics agents investigated Matta’s associates in Mexico.

The Honduran caporegime kept sending drugs and receiving weapons. He amassed such a fortune that he offered to pay the whole foreign debt of Honduras. His luck changed in 1985 when he visited his Mexican associates and got involved in the torture and murder of DEA agent Enrique Camarena.

Almost 40 years later, Matta is still in a Pennsylvania prison, and the U.S. agencies keep clashing in Honduras, a narco-state in which the United States still has the main military base of the region.

The Biden administration — committed to regaining the prestige squandered by President Biden’s predecessor, Donald Trump — faces an enormous challenge. The U.S. agenda on Honduras doesn’t typically prioritize democratic consolidation and an anti-corruption stance. But if Washington is bent on a principled foreign policy, it will have to look under the stones to find legitimate players in a country plagued by organized crime.

It’s challenging to find a politician, military chief, police officer or prominent businessman who isn’t linked to drug trafficking or corruption in Honduras. Everyone knows it, but saying it out loud is dangerous. In November 2011, on a national television program, Honduran analyst Alfredo Landaverde claimed that 14 businessmen were laundering money for the cartels and that the political parties were just fronts for organized crime. At that point, drug trafficking was already so widespread that it affected all Hondurans in one way or another. The surprising thing was that this man dared to say it out loud on national television.

Five weeks later, Landaverde was assassinated.

0 notes

Photo

“The Two Side Coin and the Permanent Bandaid” The Crisis at the U.S southern Border P2- Honduras and Kerry Committee Report In the past ,Economic reason, income inequality and poverty, was the leading reason for Hondurans to leave their country, young men searching for the American Dream, and sending back income to help their family which in return is lessening the poverty level in the country, and had helped the country economically. Now the main leading reason for migration is violence and crimes. “Another aspect of Central American migration that has changed is that migrants are no longer primarily men, but also women, teenagers and even children. Whole families travel from Honduras to the U.S. in search for a more peaceful life. By 2015 174,000 people, 4% of the country's households, had left Honduras.[9] (xiii) Yet, there is a positive correlation found in the number of unaccompined minors migration and the rate of crime. When Honduras rate of crime decreased in 2011, the number of unaccompined minors coming the U.S. also decreased from being at the top of the triangle central Americas list to the third in the list in 2016. “For several years, Honduras sent more unaccompanied minors to the United States than any other Central American country. But since the murder rate began decreasing in 2011, the number of children traveling alone has also been reduced by half. Therefore, Honduras is now third on the list of countries from whence unaccompanied Central American minors fled, totaling around 18,000 in 2016.[9] Sixty percent of unaccompanied minors report that they are fleeing violence, including physical violence, threats or extortion [5] . (xiii) since 1978, Drug business has been interconnected in with the Honduras government, that the government became partner with major drug cartel. It started with the Medellín Cartel’s lord Juan Matta-Ballesteros financing the cocaine coup where president Policarpo Paz García overthrew Juan Alberto Melgar Castro. In return for the cartel help to Paz, he offered them military and Intelligence service for a cut from their profit. A note on this powerful Medellín Cartel is considered the majority supplier of ⬇️ https://www.instagram.com/p/B0PkE2kJsHG/?igshid=1621rlxv33lfb

0 notes

Text

Racial Profiling hits Music: BYI's Spanish Trap Artist Troopnastyy !

Racial Profiling hits Music: BYI’s Spanish Trap Artist Troopnastyy !

By: Fredwill Hernandez Race or ethnicity should never dictate one’s personal taste, or the kind of music one does or makes, but if you ask [West Coast] Spanish Trap artist Adrian Delgado Pulido known artistically as Troopnastyy, that hasn’t been the case. BYI’s Spanish Trap Artist Troopnastyy in San Pedro, Ca. (Photo by: Fredwill Hernandez/The Hollywood 360) “My whole life has been…

View On WordPress

#Adrian Delgado Pulido#Beyond Your Imagination#Boland Amendments#BYI#El Nacimiento#Estevan Oriol#Fredwill Hernandez#Iran Contra Scandal#Juan Matta Ballestero#Luis "LuLu" Torres#Mister Cartoon#Nancy Reagan#Oliver North#Omar Cruz#Racial Profiling#Racial Profiling hits Music#Ronald Reagan#Sandinista National Liberation Front#SETCO#Spanish Trap#Spanish Trap Music#Trap Music#Troopnastyy

0 notes

Text

NARCO-POLITIK: “King of Cocaine” Roberto Suárez, CIA-Contra Drug Links & A DEA Agent’s Murder (Archive)

NARCO-POLITIK: “King of Cocaine” Roberto Suárez, CIA-Contra Drug Links & A DEA Agent’s Murder (Archive)

Source – ticotimes.net

– “The administration of U.S. President Ronald Reagan went into league with the largest drug traffickers of the era – Caro Quintero, Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar, the Bolivian “King of Cocaine” Roberto Suárez and Honduran trafficker Juan Matta Ballesteros – to ship copious quantities of cocaine through Costa Rica and El Salvador to the United States to help support the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

CLAROSCUROS

José Luis Ortega Vidal

(1)

Fueron dos breves encuentros con sendas fuentes informativas de primer nivel sobre la historia del periodismo en Coatzacoalcos.

Ambas lo han vivido por dentro y una de ellas desde la perspectiva historiográfica, con que aportó a una visión integral sobre el pasado de lo que en el siglo XVI fue la Villa del Espíritu Santo; posteriormente Puerto México y hoy Coatzacoalcos.

Una de las fuentes me remite a una pista: en 1911 se habría fundado el primer periódico del siglo XX en Coatzacoalcos.

Su nombre Diario del Istmo -ajeno al actual que lleva la misma nomenclatura- y su línea editorial: crítica, combativa.

La segunda fuente vivió la fundación del actual Diario del Istmo, el periódico cuya propietaria -Roselia Barajas de Robles- ha mantenido una relación política directa con Andrés Manuel López Obrador desde sus inicios en la oposición de izquierda y es la veracruzana con mayor influencia en el dirigente nacional de MORENA.

Diario del Istmo, sus intereses políticos y los nexos con AMLO explican la presencia de Rocío Nahle García junto a López Obrador, haciendo y deshaciendo en el morenismo veracruzano pero particularmente en el sur y de modo singular en Coatzacoalcos.

Aquí, la diputada federal por el distrito XI y coordinadora de la bancada de MORENA en la Cámara Baja del Congreso ha impuesto y defiende la figura de Víctor Manuel Carranza como el cuasi candidato de MORENA a la presidencia municipal.

La fuente consultada nos ubica.

Diario del Ismo cumple su papel histórico; su rol político/social; da fe a la esencia que lo vio nacer de manos de Rubén Pabello Acosta el 18 de abril de 1979.

Su cercanía con el poder; sus nexos para beneficiar y beneficiarse del poder; su papel alrededor del poder mismo.

Junto a Rubén Pabello Acosta, fundador del diario de Xalapa y del diario de Veracruz en la ciudad y puerto del mismo nombre, acudió el gobernador Rafael Hernández Ochoa a la inauguración del Diario del Istmo el último año de la década de los 70s.

Á Diario Sotavento, un añejo periódico porteño propietario del empresario chiapaneco Alfonso Grajales, le quedaban pocos años de vida.

Diario del Istmo inauguró la presencia de la tecnología de rotativa en Coatzacoalcos.

La competencia se elaboraba con linotipos.

Diario Cámara, del legendario reportero Javier Zea Salas, pasaría a la historia también.

El único periódico creado en la primera mitad del siglo XX en el sur de Veracruz y aún vigente es La Opinión de Minatitlán.

Fue, durante décadas, un diario de influencia regional.

Hoy, básicamente circula en su natal Minatitlán pero sobrevive tras haber sido fundado en 1934 y contar con casi 83 años edad, impreso en blanco y negro.

(2)

El empresario automotriz Juan Osorio López sería candidato del PRI a la presidencia de Coatzacoalcos en 1979.

La década de los 70s había sido aciaga para el priísmo en el municipio porteño. Había perdido en dos ocasiones los comicios locales.

Además, emergió otra competencia: la del periódico El Matutino dirigido por los hermanos Cárdenas Cruz, Emilio –primero- y Mussio –después- con una línea crítica hacia el sistema político tricolor.

Diario del Istmo, con una fuerte inversión privada y apoyo desde el gobierno del estado vendría a “enmendar” la plana para los intereses políticos de “la democracia perfecta”.

(3)

En el 2017, Diario del Istmo es pieza clave para los intereses que representan Rocío Nahle García, sus padrinos los Robles Barajas, su jefe AMLO, su candidato y amigo familiar Víctor Manuel Carranza y el objetivo común: el arribo una vez más al palacio municipal de Coatzacoalcos donde se manejan miles de millones de pesos.

Estos han pasado por las manos de los ex alcaldes Juan Hilllam Jiménez y su hijo Iván Hillman Chapoy, suegro y esposo de Mónica Robles Barajas, ex diputada local por el PVEM al que ha renunciado mientras su cónyuge se mantiene en el PRI como delegado de la Comisión Nacional del Agua en Tabasco tras haber contado con el mismo cargo en Veracruz.

Nada es casual

Todo es causal.

Ocurre de norte a sur, de oriente a poniente.

Los medios de comunicación y sus historias, del tamiz que sean, están siempre ligadas a la transformación del poder. A sus claros y a sus oscuros.

(4)

La noche del 9 de abril del 2005, en las cercanías de su casa en Poza Rica, fue atacado de 13 balazos mortales el periodista y propietario del periódico La Opinión: Raúl Gibb Guerrero.

La mañana de aquella jornada fatídica, el heredero del periódico más poderoso e influyente de la zona norte de Veracruz, incluyendo parte de la región totonaca y casi toda la huasteca, había inaugurado una filial en Nautla, municipio vecino de Martínez de la Torre, de San Rafael, de Misantla, de Tlapacoyan, área colindante con la frontera entre Veracruz y Puebla.

Reciente el inicio del segundo año de gobierno de Fidel Herrera Beltrán...

¿Quién o quiénes mataron al poderoso empresario periodístico?

¿Por qué?

Su extensión empresarial se generó hacia el municipio donde nacieron los hermanos Izquierdo Hebrard, cuñados de Arturo “El negro” Durazo Moreno.

Arturo y Hugo Izquierdo Hebrard trabajaron para el gobernador de Sinaloa Leopoldo Sánchez Celis.

Desde Nautla pasaron a vivir al norte del país donde conocieron a Miguel Angel Félix Gallardo, responsable de la seguridad de los hijos del gobernador sinaloense.

El llamado “Padrino”, había sido ´madrina´ y luego agente de la policía judicial federal.

Apoyado por Sánchez Celis, Félix Gallardo se convirtió en el más importante narcotraficante en México durante las décadas de los 70s y 80s.

Empezó con marihuana y amapola enviadas a Estados Unidos.

Luego se introdujo al negocio internacional de la cocaína proveniente de Colombia, puesta en México con el apoyo de su contacto el hondureño Ramón Matta Ballesteros y finalmente haciendo negocios con Pablo Escobar Gaviria, el histórico y más sangriento líder del crimen organizado de Sudamérica de que se tenga registro.

Los Izquierdo Hebrard se hicieron socios de Félix Gallardo. A la postre Le vendieron el rancho “Camino Real” ubicado cerca de su pueblo natal y a orilla de carretera.

Operaban desde ahí una pista clandestina donde avionetas llenas de droga y proveniente de Sudamérica y con destino a Estados Unidos, cargaban combustible.

En el "Camino Real” se escondió –prófugo de la justicia tras el sexenio de su protector José López Portillo, ´El negro Durazo´, aquel de los muertos del río Tula.

El periodista Ricardo Ravelo escribió el primero de octubre de 1994 en la revista PROCESO:

“Conocido en la entidad como El Padrino de la Droga, Arturo Izquierdo Hebrard, excuñado de Arturo Durazo Moreno, socio del narcotraficante Miguel Angel Félix Gallardo durante la primera mitad del decenio de los ochenta y actual empleado del gobernador Patricio Chirinos Calero, es ahora uno de los principales operadores del cártel del Golfo, que dirige Juan García Abrego, de acuerdo con información proporcionada por el delegado de la Procuraduría General de la República (PGR), José Antonio González Báez Cardoso.

Su relación con Juan Nepomuceno Guerra —tío de García Abrego, preso en Matamoros por delitos contra la salud— data de hace al menos una década, aunque ya desde principios de los ochenta tenía trato con Félix Gallardo”. (1)

(5)

Nada es nuevo. Los hombres de poder crean o empoderan medios de comunicación para sus intereses particulares.

Hay periodistas que van en busca del poder también, alejados del objetivo original: informar como ejercicio de vida.

La codicia substituye a la vocación si es que alguna vez existió.

Entran en juego los cruces fatídicos, las cartas del destino o la introducción a territorios prohibidos.

El periodismo y el poder son como dos amantes de pasión inagotable y a veces se topan con la visión de Neruda: “es tan corto el amor y tan largo el olvido”.

En ocasiones, también, como en una tragedia griega, se exterminan mutuamente en un abrazo fatal…

(1) http://ift.tt/Pw5Wb0…/arturo-izquierdo-hebrard-emplea…

0 notes

Text

Opinion: Honduras, the narco-state that illustrates U.S. contradictions

Carlos Dada is the founder and director of the news site El Faro in El Salvador.

Wherever you walk in Honduras, you are most likely in drug trafficking territory. For half a century, this country has been the Central American base for drug trafficking. Organized crime has infiltrated all institutions. If a Honduran comes across any authority — police, mayor, congressman — chances are that figure has commitments to organized crime. However, the Honduran drug trade has moved in step with the United States’ interests.

The recent New York trials against Honduran drug traffickers allow us to measure the extent of the infiltration by organized crime: military and police chiefs, politicians, businessmen, mayors and even three presidents have been linked to cocaine trafficking or accused of receiving funds from trafficking.

But the trials have a subplot that the scandalous testimonies of criminals have buried: the clash of agendas between the different U.S. agencies involved in Central America. The CIA, the Drug Enforcement Administration and the State Department have rarely acted in unison.

Juan Antonio “Tony” Hernández, brother of President Juan Orlando Hernández, was found guilty of smuggling 185 tons of cocaine into the United States and sentenced to life in prison. “Here, the [drug] trafficking was indeed state-sponsored,” U.S. District Judge Kevin Castel said in the sentence.

The jury concluded that Tony Hernández used the Honduran army and police for his criminal activities. From these earnings, he contributed large sums of money to the political campaigns of his brother and then-President Porfirio Lobo Sosa.

An American jury concluded that the brother of the Honduran president used the army and police for his criminal activities.

The case against him was the product of years of investigation by the DEA and the Justice Department into the criminal activities of the Hernández family. While the anti-drug agents followed the trail of the drug trafficker, the Honduran president received support from the State Department, which even endorsed his fraudulent 2017 reelection because the opposition leader, former president Manuel Zelaya, aligned himself with the Venezuelan regime. The DEA’s priority is to hunt down narcos. In Honduras, the State Department’s priority is to weaken the Bolivarian government of Venezuela, even if that means endorsing the fraudulent reelection of the head of the Hernández family.

Fabio Lobo, son of the former president Lobo, and banker Yani Rosenthal, son of one of the richest men in Honduras, were previously convicted in the same New York court. Rosenthal was found guilty of laundering money in their banks for the Los Cachiros cartel. He served a three-year prison sentence and returned to Honduras, where he’s currently the opposition’s presidential nominee.

In Honduras, one of the most violent countries in the world, 60 percent of deaths are attributed to organized crime. There are 37 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, and all 18 provinces are within the criminal groups’ grip. However, this isn’t something new. Large-scale drug trafficking in Honduras dates back to the 1970s. Ramón Matta Ballesteros, a Honduran born in poverty, took advantage of the geographical benefits of his country and established himself as a link between the Medellín Cartel (led by Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar) and the Guadalajara Cartel (led by Mexican drug lord Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo). He operated with the protection and collaboration of the Honduran Armed Forces, politicians and police, and became one of the wealthiest and most powerful Central Americans.

Matta set up an airline that had two clients: the Escobar cartel and the CIA. The flights went north from Colombia to the United States loaded with cocaine and emeralds and returned south to Nicaragua with weapons and ammunition for the counterrevolutionaries. Amid the Cold War, the CIA’s goal was to end the revolutionary government that the Sandinistas had installed in Nicaragua, even though the United States had already declared war on drugs.

To achieve this, the CIA needed not only Matta’s airline but the involvement of the Honduran army, which protected Matta. Years later, the Kerry committee report on support operations to the Nicaraguan Contras confirmed Matta’s involvement with the drug trafficking and the transportation of combat supplies. It also questioned the fact that DEA operations in Honduras were shut in 1983, despite evidence of military involvement and knowledge of Matta’s activities. The DEA’s anti-drug agenda collided with the anti-communist strategy of the CIA and the White House. But the anti-narcotics agents investigated Matta’s associates in Mexico.

The Honduran caporegime kept sending drugs and receiving weapons. He amassed such a fortune that he offered to pay the whole foreign debt of Honduras. His luck changed in 1985 when he visited his Mexican associates and got involved in the torture and murder of DEA agent Enrique Camarena.

Almost 40 years later, Matta is still in a Pennsylvania prison, and the U.S. agencies keep clashing in Honduras, a narco-state in which the United States still has the main military base of the region.

The Biden administration — committed to regaining the prestige squandered by President Biden’s predecessor, Donald Trump — faces an enormous challenge. The U.S. agenda on Honduras doesn’t typically prioritize democratic consolidation and an anti-corruption stance. But if Washington is bent on a principled foreign policy, it will have to look under the stones to find legitimate players in a country plagued by organized crime.

It’s challenging to find a politician, military chief, police officer or prominent businessman who isn’t linked to drug trafficking or corruption in Honduras. Everyone knows it, but saying it out loud is dangerous. In November 2011, on a national television program, Honduran analyst Alfredo Landaverde claimed that 14 businessmen were laundering money for the cartels and that the political parties were just fronts for organized crime. At that point, drug trafficking was already so widespread that it affected all Hondurans in one way or another. The surprising thing was that this man dared to say it out loud on national television.

Five weeks later, Landaverde was assassinated.

0 notes

Text

Opinion: Honduras, the narco-state that illustrates U.S. contradictions

Carlos Dada is the founder and director of the news site El Faro in El Salvador.

Wherever you walk in Honduras, you are most likely in drug trafficking territory. For half a century, this country has been the Central American base for drug trafficking. Organized crime has infiltrated all institutions. If a Honduran comes across any authority — police, mayor, congressman — chances are that figure has commitments to organized crime. However, the Honduran drug trade has moved in step with the United States’ interests.

The recent New York trials against Honduran drug traffickers allow us to measure the extent of the infiltration by organized crime: military and police chiefs, politicians, businessmen, mayors and even three presidents have been linked to cocaine trafficking or accused of receiving funds from trafficking.

But the trials have a subplot that the scandalous testimonies of criminals have buried: the clash of agendas between the different U.S. agencies involved in Central America. The CIA, the Drug Enforcement Administration and the State Department have rarely acted in unison.

Juan Antonio “Tony” Hernández, brother of President Juan Orlando Hernández, was found guilty of smuggling 185 tons of cocaine into the United States and sentenced to life in prison. “Here, the [drug] trafficking was indeed state-sponsored,” U.S. District Judge Kevin Castel said in the sentence.

The jury concluded that Tony Hernández used the Honduran army and police for his criminal activities. From these earnings, he contributed large sums of money to the political campaigns of his brother and then-President Porfirio Lobo Sosa.

An American jury concluded that the brother of the Honduran president used the army and police for his criminal activities.

The case against him was the product of years of investigation by the DEA and the Justice Department into the criminal activities of the Hernández family. While the anti-drug agents followed the trail of the drug trafficker, the Honduran president received support from the State Department, which even endorsed his fraudulent 2017 reelection because the opposition leader, former president Manuel Zelaya, aligned himself with the Venezuelan regime. The DEA’s priority is to hunt down narcos. In Honduras, the State Department’s priority is to weaken the Bolivarian government of Venezuela, even if that means endorsing the fraudulent reelection of the head of the Hernández family.

Fabio Lobo, son of the former president Lobo, and banker Yani Rosenthal, son of one of the richest men in Honduras, were previously convicted in the same New York court. Rosenthal was found guilty of laundering money in their banks for the Los Cachiros cartel. He served a three-year prison sentence and returned to Honduras, where he’s currently the opposition’s presidential nominee.

n Honduras, one of the most violent countries in the world, 60 percent of deaths are attributed to organized crime. There are 37 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, and all 18 provinces are within the criminal groups’ grip. However, this isn’t something new. Large-scale drug trafficking in Honduras dates back to the 1970s. Ramón Matta Ballesteros, a Honduran born in poverty, took advantage of the geographical benefits of his country and established himself as a link between the Medellín Cartel (led by Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar) and the Guadalajara Cartel (led by Mexican drug lord Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo). He operated with the protection and collaboration of the Honduran Armed Forces, politicians and police, and became one of the wealthiest and most powerful Central Americans.

Matta set up an airline that had two clients: the Escobar cartel and the CIA. The flights went north from Colombia to the United States loaded with cocaine and emeralds and returned south to Nicaragua with weapons and ammunition for the counterrevolutionaries. Amid the Cold War, the CIA’s goal was to end the revolutionary government that the Sandinistas had installed in Nicaragua, even though the United States had already declared war on drugs.

To achieve this, the CIA needed not only Matta’s airline but the involvement of the Honduran army, which protected Matta. Years later, the Kerry committee report on support operations to the Nicaraguan Contras confirmed Matta’s involvement with the drug trafficking and the transportation of combat supplies. It also questioned the fact that DEA operations in Honduras were shut in 1983, despite evidence of military involvement and knowledge of Matta’s activities. The DEA’s anti-drug agenda collided with the anti-communist strategy of the CIA and the White House. But the anti-narcotics agents investigated Matta’s associates in Mexico.

Lost Cause: The War on Drugs in Latin America

The Honduran caporegime kept sending drugs and receiving weapons. He amassed such a fortune that he offered to pay the whole foreign debt of Honduras. His luck changed in 1985 when he visited his Mexican associates and got involved in the torture and murder of DEA agent Enrique Camarena.

Almost 40 years later, Matta is still in a Pennsylvania prison, and the U.S. agencies keep clashing in Honduras, a narco-state in which the United States still has the main military base of the region.

The Biden administration — committed to regaining the prestige squandered by President Biden’s predecessor, Donald Trump — faces an enormous challenge. The U.S. agenda on Honduras doesn’t typically prioritize democratic consolidation and an anti-corruption stance. But if Washington is bent on a principled foreign policy, it will have to look under the stones to find legitimate players in a country plagued by organized crime.

It’s challenging to find a politician, military chief, police officer or prominent businessman who isn’t linked to drug trafficking or corruption in Honduras. Everyone knows it, but saying it out loud is dangerous. In November 2011, on a national television program, Honduran analyst Alfredo Landaverde claimed that 14 businessmen were laundering money for the cartels and that the political parties were just fronts for organized crime. At that point, drug trafficking was already so widespread that it affected all Hondurans in one way or another. The surprising thing was that this man dared to say it out loud on national television.

Five weeks later, Landaverde was assassinated.

0 notes

Link

But in the South Florida courtroom, the testimony of José Santos Peña also implicated Julián Pacheco Tinoco, a former Honduran military official with long ties to the U.S. security apparatus.

A U.S. prosecutor asked the informant about a meeting in Honduras he had participated in a few years earlier. The purpose of the meeting with Honduras’s current security minister and then head of military intelligence Pacheco Tinoco was “so that he could give me help to receive shipments from Colombia to Honduras,” the informant told the court.

“What type of shipments?” the prosecutor asked.

“Cocaine,” the informant clarified.

According to the prosecution, one of the defendants in the case had deleted from his Samsung phone chat records and contact information bearing Pacheco’s name. But the allegation that the top security official of one of the United States’s closest regional allies was involved in drug trafficking was treated as a nonevent in Washington; not a single major media story mentioned the DEA informant’s testimony.

In March 2017, this time in a New York courtroom, Pacheco’s name would once again come up. More details of his and other Honduran government officials’ alleged involvement in drug trafficking were revealed.

Today, Pacheco remains the minister of security, in charge of the entire Honduran national police force. With hundreds of millions of dollars of U.S. assistance pouring into Honduras’s security forces, Pacheco is one of the most important players in the country’s security and counternarcotics cooperation with the United States.

In an e-mailed statement, Tim Rieser, the foreign policy aide to Sen. Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., said the senator is concerned with the allegations, but that more facts are needed. Leahy “believes the State Department should be looking at this carefully because the Security Minister needs to be someone of unimpeachable integrity,” Rieser wrote.With future funding for Honduras threatened by some members of Congress — including Leahy — Pacheco was in Washington, D.C., earlier this month. It wasn’t the first time he had made a trip to protect the U.S.-Honduran relationship.

Pacheco’s connection with the United States dates back decades. As a 21-year-old cadet, Pacheco traveled to the U.S. military’s School of the Americas in Fort Benning, Georgia. In September 1979, he graduated from a course on counterinsurgency tactics.

With the election of Ronald Reagan the following year, Honduras took on new prominence as a U.S. ally and as a staging ground for covert American support for the contra right-wing insurgency in Nicaragua. U.S. security aid to the country skyrocketed, as did allegations that the Honduran military was involved in drug trafficking and in dozens of disappearances of activists. U.S. diplomats largely looked the other way.

In the spring of 1986, at the height of the United States’s Cold War efforts in Central America, Pacheco was once again at the School of the Americas. This time, having been promoted to lieutenant, Pacheco graduated from a course in psychological operations.

After the Berlin Wall fell, the Pentagon changed tack in Central America and began focusing more on the “War on Drugs.”In April 1988, the most notorious Honduran trafficker at the time, Juan Ramón Matta Ballesteros, was arrested and sent to the United States. As a key interlocutor between the Medellin Cartel in Colombia and Mexican traffickers, Ballesteros had compromised the highest levels of the Honduran military and government. He had also been a U.S. ally and owned a CIA-linked airline that had funneled weapons to the Nicaraguan contras – while sending drugs north.

Honduras’s constitution barred extradition, but working with rogue elements in the Honduran military, U.S. Marshal agents facilitated the capture of Matta Ballesteros. He was brought to the Dominican Republic, where he was officially turned over to U.S. authorities. The Honduran military officers who participated in the rendition were eventually criminally charged in their home country.

The following year, the United States invaded Panama, turning on another erstwhile ally involved in drug trafficking, Gen. Manuel Noriega. Noriega himself was head of military intelligence before becoming president and had been “our man in Panama,” receiving regular CIA payments for decades. Anyone – no matter their criminal record – could be a U.S. ally. That is, until they weren’t.

In Honduras, shifting U.S. priorities, a decrease in funding, and the arrest of Matta Ballesteros pushed the military into the background — at least for a little while. In June 2009, a military coup d’état ousted left-leaning elected president, Manuel Zelaya, who was dropped off in Costa Rica in his pajamas.

With relations tested, and the U.S. having temporarily suspending security assistance, then-Col. Pacheco Tinoco was sent to Washington, D.C., by the head of the Honduran armed forces. His mission was to convince the United States that the military acted properly, that there was no coup.

9 notes

·

View notes

Link

CLAROSCUROS

José Luis Ortega Vidal

(1)

El primer argumento surge de una hipótesis; el segundo es el análisis de una realidad. Veamos:

A lo largo de numerosas entregas de Claroscuros hemos ventilado información –recogida en vivencias reporteriles propias, hemerotecas, testimonios de periodistas veteranos, libros sobre el tema y autoridades políticas y policiacas- en el sentido de que en Veracruz la delincuencia organizada es tan añeja como la de buena parte del territorio nacional.

Antes de que se llamaran cárteles, las agrupaciones dedicadas a la siembra y trasiego de droga –marihuana principalmente- ya operaban en Veracruz, lo mismo que los llamados contrabandistas: los relativos al tráfico de productos comerciales extranjeros, sin pagar impuestos y por tanto abaratados e ilegales.

En el ejercicio de la historia –como ciencia- a toda línea temporal corresponde un contexto determinado.

Arturo García Niño -investigador de la Universidad Veracruzana- hizo pública una serie de artículos acerca Veracruz en la historia del narcotráfico y lo ubicó desde la época de su prohibición; esto es en el contexto del antes, durante y el después de la versión armada de la Revolución Mexicana: 1910-1917.

Concretamente, García Niño centra su investigación en el período 1920-2013.

“Ciudad Juárez en el inicio

Del siglo XX, cuando como secuela del terremoto del 18 de abril de 1906 en San Francisco algunos delincuentes de origen chino que ahí tenían sus negocios se desplazaron hacia El Paso, Texas; otros cruzaron la frontera con México para instalarse en la ciudad chihuahuense donde, establecidos ya y utilizando como parapetos lavanderías y cafeterías que en la trastienda funcionaban como fumaderos de opio y picaderos de morfina, empezaron a tender las redes de este lado, donde ya Sam Hing, el primer capo que existió en la región, controlaba desde la esquina en que hoy se encuentran las calles Oregon y avenida Paisano, en El Paso, la distribución de opio y morfina.

Daría inicio así y desde ahí un lucrativo negocio que durante los siguientes quince años, con cierta tolerancia de parte de las autoridades locales, le signaría el rostro a la ciudad para erigirla en el imaginario nacional y estadounidense como emblemático territorio donde toda actividad ilegal era no sólo posible, sino normal, hasta que en 1920, al calor de la llegada al poder central del grupo sonorense con Obregón y Calles a la cabeza, el ejército llevó a afecto la primera acción en contra del narcotráfico (y una más en contra de los chinos) de que se tenga memoria en Ciudad Juárez, para catear cinco fumaderos y picaderos de opio y morfina, incautar drogas (entre ellas cocaína, que aún no era tan de uso común como las dos anteriormente referidas) y apresar a los dueños de tales lugares, entre los que se encontraba un mexicano: Rafael L. Molina; los otro cuatro eran chinos.” (1)

(2)

En uno de varios encuentros con Ricardo Ravelo, autor de diversos libros sobre el tema del narcotráfico en México surgió el tema: ¿qué te falta?

Palabras más, palabras menos, el periodista veracruzano de fama internacional respondió: “La joya de la corona; entrevistar a Miguel Angel Félix Gallardo”.

Nativo de Sinaloa, alguna vez “madrina” y luego agente de la policía judicial federal, el llamado “padrino” o “fefe de jefes” fue guarura de los hijos, ahijado y socio del gobernador sinaloense Leopoldo Sánchez Celis durante el período 1962-1968.

Félix Gallardo fue el fundador de los cárteles en México con la creación del cártel de Guadalajara vía sus socios Rafael Caro Quintero, Ernesto “Don Neto” Fonseca –tío de Amado Carrillo Fuentes, el señor de los cielos- y con el apoyo del político priísta Sánchez Celis.

(3)

Hasta bien entrado el siglo XX la mariguana no era un producto que se traficara porque no estaba prohibida. De hecho hasta 1920 era legal y se le reconocía como un producto medicinal.

Datos substanciales sobre la historia de la prohibición de las drogas en el mundo son detallados por Hugo Vargas en su texto “De cómo se prohibieron las drogas en México” (2)

(4)

La hipótesis aludida en el párrafo uno plantea la idea de que en México como en la mayoría de los países –desde luego Estados Unidos juega un papel protagónico al respecto- la historia del uso de drogas es tan añeja como la humanidad misma.

Ha sido durante el siglo XX cuando su empleo se asoció a la idea de que daña la salud, es responsable de procesos de descomposición social y por tanto se ha prohibido su uso bajo dos argumentos: uno de salud y otro jurídico.

Tal prohibición, empero, oculta un tercer elemento de fondo: el mercantilismo; el de los intereses económicos y de control geopolítico que generó no tanto el uso legal de drogas como su prohibición.

Dicho de otro modo: a los grupos de poder en el mundo les ha resultado un negocio sin precedente prohibir las drogas que se usaban legalmente hasta 90 años atrás y tal prohibición va de la mano de matanzas –Felipe Calderón Hinojosa y Enrique Peña Nieto como co-responsables en México- del negocio de producción y tráfico de armas; del control e impulso del tráfico humano y sobre todo del mantenimiento de un status quo respecto al poder político.

El chapo Guzmán fue aprendiz, chalán y heredero hábil del emporio de Rafael Caro Quintero y Ernesto Fonseca “Don neto”.

Estos, fueron socios del “padrino” y subalternos de Miguel Angel Félix Gallardo.

Félix Gallardo empezó como “madrina” y luego fue agente de policía judicial federal para pasar a contrabandear marihuana y amapola desde México al principal mercado de consumo de drogas en el mundo: Estados Unidos.

Al poco tiempo –décadas de los 70s y 80s- “el jefe de jefes” se asoció con traficantes colombianos de cocaína como Pablo Escobar Gaviria -vía el hondureño Juan Ramón Matta Ballesteros- y se convirtió en el más importante narcotraficante de México; en el más poderoso introductor de cocaína, amapola y marihuana a EEUU.

Todo esto ocurrió con la complicidad de políticos de todos los niveles y con policías municipales, estatales y federales, así como integrantes de las fuerzas armadas en nuestro país.

¿Por qué? ¿Cómo fue posible la creación de esta infraestructura criminal sin precedente? ¿Cuál es el papel del Estado en esta red de complicidades?

Miguel Angel Félix Gallardo –que usó pistas clandestinas en Veracruz apoyado con cómplices locales de sur a norte de la entidad- en realidad representa una historia menor; el hilo de una madeja que inicia con el siglo XX…

“En el mundo se advertían ya los primeros intentos por lograr una legislación internacional sobre el tema. En 1904, promovida por Estados Unidos, se llevó a cabo, en Shangai, una convención sobre el opio, sin resultados concretos. México no asistió. Años después, en 1912, se realizó en La Haya otra convención internacional. En esa ocasión el gobierno de Madero envió un representante a la reunión, que tampoco tuvo mucho éxito debido a la ausencia de Turquía y Austria-Hungría y porque Inglaterra –dice Escohotado– sólo quería hablar de morfina y cocaína, y Alemania protestaba en nombre de sus poderosos laboratorios, alegando que Suiza no estaba presente y aprovecharía las restricciones en su beneficio; Portugal protegía el opio de Macao, y Persia (hoy Irán) sus cultivos ancestrales de amapola; Holanda producía cientos de toneladas de cocaína en Java, y Francia reportaba excelentes ingresos por el consumo de opiáceos en Indochina; Japón, como parte de sus maniobras para invadir China, introducía a ese país morfina, heroína e hipodérmicas; Rusia contaba con una producción de opio nada desdeñable, e Italia se retiró de la reunión luego que fue rechazada su propuesta de incluir el tema del cannabis.” (3)

Y en México ha incluido e incluye la corrupción de nuestro gobierno en todos sus niveles y sus múltiples rostros.

Históricamente, este tema nos conduce a su vez a un punto clave en el escenario de la segunda guerra mundial.

Turquía deja de surtir opio –esencial en la fabricación de morfina- a Estados Unidos; país que lo requiere con urgencia en los campos de batalla para salvar la vida de sus soldados.

Es la década de los 40s. Estamos en el sexenio del general Manuel Avila Camacho y se establece un pacto secreto entre los gobiernos norteamericano y mexicano: incrementar la siembra de amapola en nuestro territorio para surtir al sector farmacéutico militar en el país que hoy gobierna Donald Trump.

Trasladan a especialistas para capacitar en la producción rápida de la variante de amapola que permite producir opio y campesinos mexicanos son empleados para cultivarla como si fuera maíz o frijol…

El escenario que se emplea es la sierra del triángulo dorado –Chihuahua, Durango, Sinaloa- donde nacerían después Miguel Angel Félix Gallardo, “el padrino, con sus derivados: los zetas, cártel del golfo, cártel de Sinaloa, Jalisco nueva generación, los Arellano Félix, los Beltrán Leyva, los cárteles de Guerrero y Michoacán, el chapo, etcétera.

Al terminar la segunda guerra mundial quisieron acabar con una cultura que había llegado con los chinos desde fines del siglo XIX y que se impulsó oficialmente en la década de los 40s.

Nuestra hipótesis consiste en advertir que desde entonces todo ha sido una novela trágica, con millones de víctimas, muchas inocentes, frente al enriquecimiento bestial de seres infernales como los narcotraficantes.

Todo bajo el manejo, el dominio, el beneficio de una clase política hipócrita y asesina: la mexicana, la de sus socios norteamericanos y la del resto del mundo que forma parte de una red imposible de desaparecer en Sudamérica, Europa, Asia, Africa.

Siempre con el mismo escenario: unos cuantos convirtiéndose en multimillonarios y muchos pagando con su libertad, su vida o sufrimiento la existencia del narcotráfico, del crimen organizado y sus redes inhumanas.

De los consumidores, la gran mayoría son, en sentido estricto, enfermos que pagan con dinero, esclavitud o sus vidas el haberse adentrado en este universo dantesco.

Este, también, ha sido y es el caso de Veracruz.

La clase política está embarrada. La historia del narcotráfico inicia y termina en sus oficinas.

(5)

El análisis de una realidad:

“Desde este momento comienza la guerra, guerra quieren, guerra tendrán, quieren tener todo el poder para meter a su gente, pero aquí nos morimos todos”

Tal, fue el texto que apareció junto a los cuerpos de 11 ejecutados -9 hombres y dos mujeres- la noche del pasado 28 de febrero en “La tampiquera”, Boca del Río, Veracruz.

Se trata de una lucha entre bandas, dijo el gobernador Miguel Angel Yunes Linares.

“No nos van a doblegar” declaró ante diputados Miguel Angel Osorio Chong.

Dos apreciaciones distintas sobre una misma realidad: el mensaje fue entre narcos y fue para políticos.

Se han dado a conocer dos casos: el del joven Antonio Vergara Capetillo, de 18 años, y Shantal Juárez Santillán, de 24, sobre quienes no se habrían encontrado antecedentes delincuenciales. (4)

Es decir, Miguel Angel Yunes Linares estaría equivocado al victimizar a los ejecutados y señalar que todos eran delincuentes.

Hasta ahora dos de ellos, por lo menos, no lo serían.

A tres meses de la elección de alcaldes Veracruz hiede a sangre por el poder.

0 notes