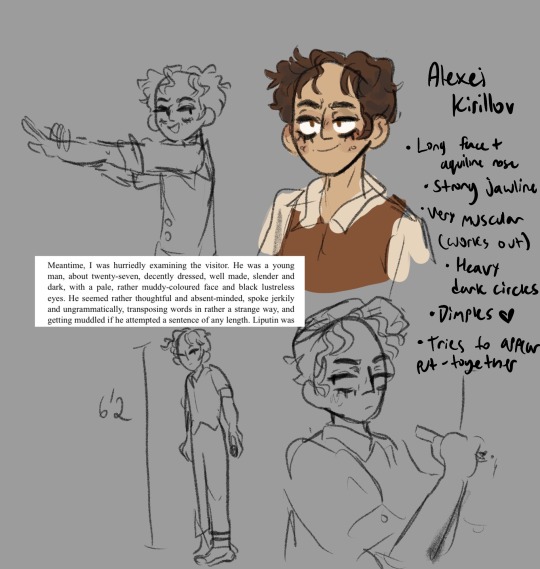

#kirillov my beloved.....

Photo

Aleksey Kirillov and Pëtr Verkhovensky | Бесы (Demons), 2014

#[gently caress his hair] now take blame for the murders my beloved#alexey kirillov#kirillov#алексей кириллов#pyotr verkhovensky#verkhovensky#пётр верховенский#dostoevsky#the demons#the possessed#demons 2014#бесы#бесы 2014#достоевский#my gif edit

143 notes

·

View notes

Photo

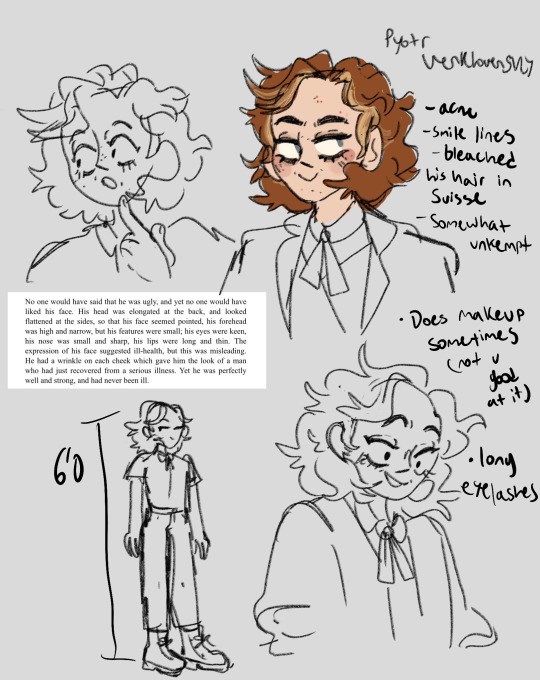

oh yeah funky russians

#so true#ivan shatov my beloved#ivan shatov#pyotr verkhovensky#darya shatova#dasha shatova#alexei kirillov#demons#the possessed#fyodor dostoyevsky#dostoevsky tag#ruslit#russian literature#my art#fanart#books#Бесы

47 notes

·

View notes

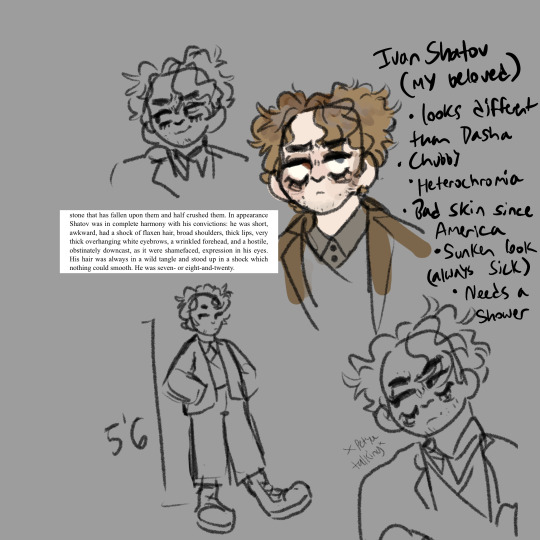

Photo

Laurus by Eugene Vodolazkin

Medieval Russia was a land trembling with religious fervor. Mystics, pilgrims, prophets, and holy fools wandered the countryside. Their wardrobe and grooming choices earned them names like Maksim the Naked and John the Hairy. Basil the Blessed walked through Moscow in rags, castigated the rich, exposed deceitful merchants, and issued prophecies, many of which proved correct, or close enough. St. Basil’s Cathedral in Red Square is named for him. Nil Sorsky was renowned for his asceticism and devotion, suggesting that, through self-discipline and prayer, you could directly commune with God, making irrelevant the extravagant rituals of Orthodoxy. Many ascetics were deemed “fools for Christ,” whether or not they behaved foolishly. Some were designated saints.

A new novel by the Russian medievalist Eugene Vodolazkin, “Laurus,” recreates this fervent landscape and suggests why the era, its holy men, and the forests and fields of Muscovy retain such a grip on the Russian imagination. Vodolazkin’s hero-mystic Arseny is a protagonist extrapolated from the little that is known about the lives and deeds of the famous holy men. Born in 1440, he’s raised by his herbalist grandfather Christofer near the grounds of the Kirillov Monastery, about three hundred miles north of Moscow. He becomes a renowned medicine man, faith healer, and prophet who “pelted demons with stones and conversed with angels.” He makes a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. He takes on new names, depending on how he will next serve God. The people venerate his humble spirituality. In “Laurus,” Vodolazkin aims directly at the heart of the Russian religious experience and perhaps even at that maddeningly elusive concept that is cherished to the point of cliché: the Russian soul.

So much of that soul seems to be wrapped up in Russia’s relationship with the natural world: intimate but wary, occult but practical. Arseny’s initial renown comes from his success as an herbalist and healer as he employs what he learned from his beloved grandfather. For wart removal, the best treatment is a sprinkling of ground cornflower seeds. For burns, apply linen with ground cabbage and egg white. The white root of a plant called hare’s ear cures erectile dysfunction. (“The drawback to this method was that the white root had to be held in the mouth at the crucial moment.”) At least some of Arseny’s remedies are suspect. (Translator Lisa C. Hayden warns, “Please don’t try these at home.”)

The remedies invoke an idea of nature as essentially friendly, or at least potentially helpful. Folk medicine remains popular in Russia to this day. Whether or not it’s effective, it connects an overwhelmingly urbanized population to the scythed fields and profound, spirit-dwelling forests of its antiquity. And Vodolazkin takes his holy fools seriously, offering a view of medieval Christianity that goes well beyond the appropriation of home remedies for religious purposes. Although Arseny cherishes Christofer’s birch-bark pharmaceutical texts, he doesn’t believe the herbs are responsible when the ill recover. (Often, they don’t.) The keys are prayer and faith. He bows to icons on a shelf. Incense burns. A vitalizing current runs from his hands into the core of the patient’s suffering. In “Laurus,” the depiction of faith is presented entirely without irony—a strategy that has become unusual among literary writers, but which is central to Vodolazkin’s effort to excavate what was meaningful from Russia’s distant past.

The faith of Vodolazkin’s holy fools is neither ecstatic, like many forms of Western Christianity, nor hierarchical, like Eastern Christianity, nor scholarly, like Judaism. Although the Greek-derived word doesn’t appear in “Laurus,” Arseny appears to embrace “Hesychasm,” the Byzantine religious movement in pursuit of inner peace. In his magisterial history of Russian culture, “The Icon and the Axe,” James H. Billington explains that the Hesychasts received “divine illumination” through “ascetic discipline of the flesh and silent prayers of the spirit.” This often required years of isolation and silence. Arseny accepts the challenge after a series of trials, most significantly the death of his beloved Ustina, a young woman who had found refuge in his log house after her family was lost to the plague. His botched attempt to deliver their child tests the limits of prayer and folk medicine: “The blood was flowing from the womb and he could not stanch it. He took some finely grated cinnabar in his fingers and went as deeply into Ustina’s female places as he could.” Arseny acknowledges his malpractice, but not the fact that she’s gone forever. Shattered by her death, he journeys to the town of Pskov, in what was then Lithuania. He spends decades without speaking, and is designated one of the region’s three holy fools. Most of his silent communion is not with God, but with Ustina’s spirit.

The other element of being a Russian holy man was a taste for prophecy—”dominating all other manifestations of eccentric sanctity,” according to Sergei Ivanov, author of “Holy Fools in Byzantium and Beyond,” the most authoritative English-language account of the phenomenon. “For many holy fools the power to predict is virtually the only quality mentioned in the sources.” Arseny looks at the ill and knows, regardless of his ministrations, who will survive and who will die. As a boy fool-in-training, he peers into the fire of the stove and sees the image of an elderly man. The aged Arseny will gaze into another fire at the unlined face of himself as a boy.

With so many of the blessed running around, fifteenth-century Russia, as Vodolazkin depicts it, is the golden age of prophets. Similarly ragged and unkempt, they stand at the entrances of markets. They appear at christenings and weep for the truncated lives they foretell. They sleep in cemeteries. Since there are seven days in the week, they figure that God has ordained seven millennia of human existence. Thus they widely announce that the world will end seven thousand years after its creation in 5508 B.C.—in other words, in A.D. 1492, just around the corner. Beset by plague and pestilence, poverty and hunger, the Russians already sense themselves on the brink of annihilation. They’re receptive. In the West, especially in Spain, other Christians similarly anticipate the apocalypse.

Arseny’s Italian friend Ambrogio, who has come to Russia because of its hospitality to prophets, predicts floods to the day; he can also see within a Soviet linen shop, circa 1951. But his visions of 1492 are confused. “On the one hand, a new continent would be discovered, on the other, the end of the world was expected in Rus’.” Ambrogio joins Arseny for his journey to Jerusalem. Passing through Poland, on their way to the Mediterranean, the two holy men reach the small town of Oświęcim. Ambrogio says, “Believe me, O Arseny, this place will induce horrors in centuries. But its gravity can be felt, even now.”

The prophets put forward a peculiar explanation for their extraordinary visions. They don’t necessarily attribute it to their spirituality. They see soothsaying as a kind of physical phenomenon, related to either the circularity of time or to its illusoriness. Ambrogio goes as far as to say that there’s really no such thing as time. The sense of its passing “is given to us by the grace of God so we will not get mixed up, because a person’s consciousness cannot take in all events at once. We are locked up in time because of our weakness.”

The semi-rational notions of the two mystics resonate in a particularly contemporary register, as fifteenth-century Russian religious thought grazes against the theories of relativity and quantum mechanics. Some current-day scientists, particularly the heterodox British physicist Julian Barbour, have speculated that the theories imply our universe exists in a kind of frozen space-time, in which everything that has ever happened and everything that will ever happen is occurring right now, in a single gigantic instant. The world has already ended. Kurt Vonnegut’s Tralfamadorians told the holy wanderer Billy Pilgrim something like that, too. If correct, the human experience of time flowing like a river is more a function of our physiology: a singularly intense hallucination. The minutes may indeed pass by the grace of God.

In “Laurus,” Vodolazkin conveys the simultaneity of existence in his use of language, which, as the translator notes, “blends archaic words, comic remarks, quotes from the Bible, bureaucratese [and] chunks of medieval texts.” Hayden has tried to do justice to these stylistic flourishes by mixing Old English locutions and spelling—”yonge,” for young, “wombe” for womb, and “sayde” for said—with contemporary slang. After Arseny gets beat up for exposing the local baker’s transgressions, his fellow holy fool Foma warns, “Your clock will be cleaned again, my friend.” At the Church of the Dormition of the Mother of God, dust motes caught in a ray of sunlight swirl “in a pensive Brownian dance”—a reference to molecular Brownian motion explained by Albert Einstein in 1905.

We live in an age in which the pre-modern frequently comes flush up against the modern and the post-. But Russia and Russian life seem to be especially prone to existing on several planes of time at once. Occasionally, certain Russians cry out that they can see the future. Others dwell in the Byzantine. They may pass you on a Moscow street, robed and bearded. On an autumn walk through the countryside, you may get five bars on your phone while a distant onion dome rises above a stand of birches, a kerchiefed woman on the side of the road sells a kilo of pickles, other women scout for mushrooms in the woods, and in the fields there is a humming swish!, accompanied by the quick gray blur of a long, curving blade on a stick.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Year So Far Book Ask

I was tagged by @lizlensky. Ohh thank you Liz my beloved ❤

1. Best book you have read in 2021 so far?

“The Demons” by F. M. Dostoevskij. Easily the best of the year, most likely one of my favourites of my life. What can I say, I’m weak.

2. Best sequel you have read in 2021 so far?

I haven’t been invested in any saga recently ):

No sequels for me.

3. A new release you want to check out?

4. Most anticipated book release of the second half of the year?

This is embarassing. I’ve been out of touch with publications for such a long time (basically since I started university and put aside reading-for-pleasure to pick up reading-for-academic-purposes) and now I don’t really know what to expect. If my favourite local historian is still alive, I’d like to check for his most recent and upcoming publications.

5. Biggest disappointment?

Something something by Maksim Gorkij. A little thing composed of three short stories.

6. Biggest surprise?

“Io venia pien d’angoscia a rimirarti” by M. Mari. A pleasant little thing.

7. Favourite new author (either new to you or debut)?

Gipi. I knew him already from some stealing-reading his novels at the book shop, but only got the chance to buy and actually read his works this year. Interesting author and artist, highly recommended 👀

8. Favourite new fictional crush?

Next.

9. Newest favourite character?

Aleksej Nilič Kirillov.

10. A book that made you cry?

I’m such an emotional little lad, alright? I cried so much reading “Evgenij Onegin” to the point some pages are now forever stained with tears. The surprise is that I haven’t cried for a book since.

11. A book that made you happy?

The “Reisebilder” by H. Heine is the book that made me the happiest, may it be that the author was a little shit, may it be that I used to read the journal at my favourite place in town, sitting in the garden with a glass of Bellini hehe.

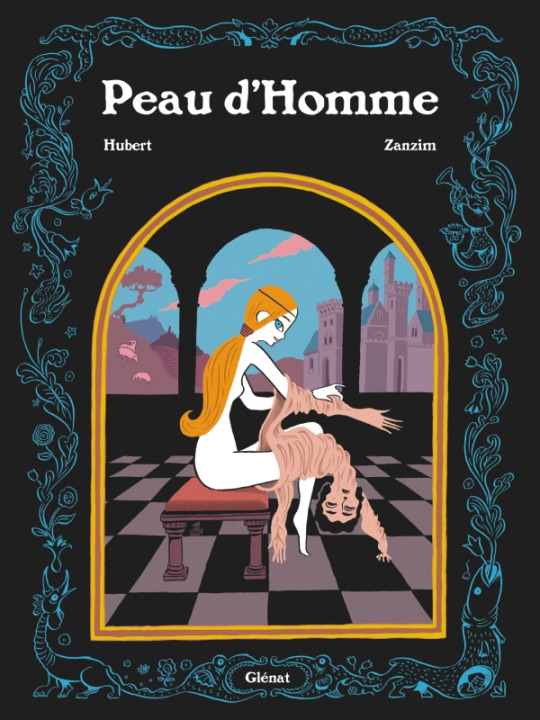

12. Most beautiful book you have bought or received this year?

13. What book do you need to read by the end of the year?

I plan to finish reading “The White Guard” by M. A. Bulgakov (thank you püm my dearest) by the end of the month.

Then I’d like to read “The Hearing Trumpet” by L. Carrington, “The Foundation Pit” by A. P. Platonov, “Il delirio di Ivan: Psicopatologia dei Karamazov” (Ivan’s delirium: Psychopathology of the Karamazovs) by A. Semerari, etc. etc.

I don’t want to annoy anyone with tagging. I’m shy 👉👈 @.mutuals do this

#thank you so much for tagging me liz!#all of a sudden i felt like i read nothing ever in my life bsdfghj#sorry for my basic taste guys i am a basic bitch#:))#hope tp spicy it in the second half of the year (starting from some good ol' anarchy essay) /j

7 notes

·

View notes