#local ageless oracle

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

576 notes

·

View notes

Photo

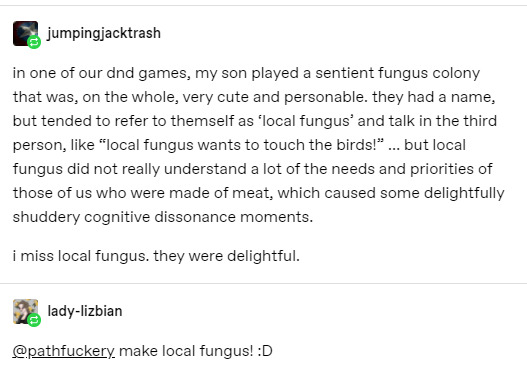

@lady-lizbian Ooooh, this one was very fun! I had to think for awhile on how to make Local Fungus. Obviously they are a leshy, but what class? What do they do? There’s a lot of room for interpretation. One might think Druid best embodies the full-on Fungus Route, but I went with a slightly different interpretation. Local Fungus, Leshy Oracle 5 Heritage: Fungus Leshy (Duh) Background: Herbalist Str 14 Dex 10 Con 18 Int 8 Wis 16 Cha 19 Skills: Trained in Herbalism, Occultism, Religion, and Society Expert in Undead Lore, Deception and Nature

Class Feats: Reach Spell, Divine Access (Choosing Norgorber for Illusory Disguise, Invisibility, and Phantasmal Killer) Ancestry Feats: Ageless Spirit, Harmlessly Cute, Ritual Reversion Skill Feats: Root Magic, Additional Lore (Undead) General Feat: Ancestral Paragon (Snagging Leshy Superstition) Mystery: Ancestors Domain: Death Local Fungus is an enigmatic horror. An ancestry oracle receiving guidance from the inscrutable Norgorber, No one knows what’s going on behind Local Fungus’ sweet smile. They receive pulls and prods from the spores of their ancestors, which cling to them and guide them. They are ageless, superstitious, and masters of the magic on the fringe. Their spell list gives them control over life and death, and they plod on, disrupting that cycle as they see fit.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

trump’s reality TV gig

Expedition: Robinson,” a Swedish reality-television program, premièred in the summer of 1997, with a tantalizing premise: sixteen strangers are deposited on a small island off the coast of Malaysia and forced to fend for themselves. To survive, they must coöperate, but they are also competing: each week, a member of the ensemble is voted off the island, and the final contestant wins a grand prize. The show’s title alluded to both “Robinson Crusoe” and “The Swiss Family Robinson,” but a more apt literary reference might have been “Lord of the Flies.” The first contestant who was kicked off was a young man named Sinisa Savija. Upon returning to Sweden, he was morose, complaining to his wife that the show’s editors would “cut away the good things I did and make me look like a fool.” Nine weeks before the show aired, he stepped in front of a speeding train.

The producers dealt with this tragedy by suggesting that Savija’s turmoil was unrelated to the series—and by editing him virtually out of the show. Even so, there was a backlash, with one critic asserting that a program based on such merciless competition was “fascist television.” But everyone watched the show anyway, and Savija was soon forgotten. “We had never seen anything like it,” Svante Stockselius, the chief of the network that produced the program, told the Los Angeles Times, in 2000. “Expedition: Robinson” offered a potent cocktail of repulsion and attraction. You felt embarrassed watching it, Stockselius said, but “you couldn’t stop.”

In 1998, a thirty-eight-year-old former British paratrooper named Mark Burnett was living in Los Angeles, producing television. “Lord of the Flies” was one of his favorite books, and after he heard about “Expedition: Robinson” he secured the rights to make an American version. Burnett had previously worked in sales and had a knack for branding. He renamed the show “Survivor.”

The first season was set in Borneo, and from the moment it aired, on CBS, in 2000, “Survivor” was a ratings juggernaut: according to the network, a hundred and twenty-five million Americans—more than a third of the population—tuned in for some portion of the season finale. The catchphrase delivered by the host, Jeff Probst, at the end of each elimination ceremony, “The tribe has spoken,” entered the lexicon. Burnett had been a marginal figure in Hollywood, but after this triumph he, too, was rebranded, as an oracle of spectacle. Les Moonves, then the chairman of CBS, arranged for the delivery of a token of thanks—a champagne-colored Mercedes. To Burnett, the meaning of this gesture was unmistakable: “I had arrived.” The only question was what he might do next.

A few years later, Burnett was in Brazil, filming “Survivor: The Amazon.” His second marriage was falling apart, and he was staying in a corporate apartment with a girlfriend. One day, they were watching TV and happened across a BBC documentary series called “Trouble at the Top,” about the corporate rat race. The girlfriend found the show boring and suggested changing the station, but Burnett was transfixed. He called his business partner in L.A. and said, “I’ve got a new idea.” Burnett would not discuss the concept over the phone—one of his rules for success was to always pitch in person—but he was certain that the premise had the contours of a hit: “Survivor” in the city. Contestants competing for a corporate job. The urban jungle!

He needed someone to play the role of heavyweight tycoon. Burnett, who tends to narrate stories from his own life in the bravura language of a Hollywood pitch, once said of the show, “It’s got to have a hook to it, right? They’ve got to be working for someone big and special and important. Cut to: I’ve rented this skating rink.”

In 2002, Burnett rented Wollman Rink, in Central Park, for a live broadcast of the Season 4 finale of “Survivor.” The property was controlled by Donald Trump, who had obtained the lease to operate the rink in 1986, and had plastered his name on it. Before the segment started, Burnett addressed fifteen hundred spectators who had been corralled for the occasion, and noticed Trump sitting with Melania Knauss, then his girlfriend, in the front row. Burnett prides himself on his ability to “read the room”: to size up the personalities in his audience, suss out what they want, and then give it to them.

“I need to show respect to Mr. Trump,” Burnett recounted, in a 2013 speech in Vancouver. “I said, ‘Welcome, everybody, to Trump Wollman skating rink. The Trump Wollman skating rink is a fine facility, built by Mr. Donald Trump. Thank you, Mr. Trump. Because the Trump Wollman skating rink is the place we are tonight and we love being at the Trump Wollman skating rink, Mr. Trump, Trump, Trump, Trump, Trump.” As Burnett told the story, he had scarcely got offstage before Trump was shaking his hand, proclaiming, “You’re a genius!”

Cut to: June, 2015. After starring in fourteen seasons of “The Apprentice,” all executive-produced by Burnett, Trump appeared in the gilded atrium of Trump Tower, on Fifth Avenue, to announce that he was running for President. Only someone “really rich,” Trump declared, could “take the brand of the United States and make it great again.” He also made racist remarks about Mexicans, prompting NBC, which had broadcast “The Apprentice,” to fire him. Burnett, however, did not sever his relationship with his star. He and Trump had been equal partners in “The Apprentice,” and the show had made each of them hundreds of millions of dollars. They were also close friends: Burnett liked to tell people that when Trump married Knauss, in 2005, Burnett’s son Cameron was the ring bearer.

Trump had been a celebrity since the eighties, his persona shaped by the best-selling book “The Art of the Deal.” But his business had foundered, and by 2003 he had become a garish figure of local interest—a punch line on Page Six. “The Apprentice” mythologized him anew, and on a much bigger scale, turning him into an icon of American success. Jay Bienstock, a longtime collaborator of Burnett’s, and the showrunner on “The Apprentice,” told me, “Mark always likes to compare his shows to great films or novels. All of Mark’s shows feel bigger than life, and this is by design.” Burnett has made many programs since “The Apprentice,” among them “Shark Tank,” a startup competition based on a Japanese show, and “The Voice,” a singing contest adapted from a Dutch program. In June, he became the chairman of M-G-M Television. But his chief legacy is to have cast a serially bankrupt carnival barker in the role of a man who might plausibly become the leader of the free world. “I don’t think any of us could have known what this would become,” Katherine Walker, a producer on the first five seasons of “The Apprentice,” told me. “But Donald would not be President had it not been for that show.”

Tony Schwartz, who wrote “The Art of the Deal,” which falsely presented Trump as its primary author, told me that he feels some responsibility for facilitating Trump’s imposture. But, he said, “Mark Burnett’s influence was vastly greater,” adding, “ ‘The Apprentice’ was the single biggest factor in putting Trump in the national spotlight.” Schwartz has publicly condemned Trump, describing him as “the monster I helped to create.” Burnett, by contrast, has refused to speak publicly about his relationship with the President or about his curious, but decisive, role in American history.

Burnett is lean and lanky, with the ageless, perpetually smiling face of Peter Pan and eyes that, in the words of one ex-wife, have “a Photoshop twinkle.” He has a high forehead and the fixed, gravity-defying hair of a nineteen-fifties film star. People often mistake Burnett for an Australian, because he has a deep tan and an outdoorsy disposition, and because his accent has been mongrelized by years of international travel. But he grew up in Dagenham, on the eastern outskirts of London, a milieu that he has recalled as “gray and grimy.” His father, Archie, was a tattooed Glaswegian who worked the night shift at a Ford automobile plant. His mother, Jean, worked there as well, pouring acid into batteries, but in Mark’s recollection she always dressed immaculately, “never letting her station in life interfere with how she presented herself.” Mark, an only child, grew up watching American television shows such as “Starsky & Hutch” and “The Rockford Files.”

At seventeen, he volunteered for the British Army’s Parachute Regiment; according to a friend who enlisted with him, he joined for “the glitz.” The Paras were an élite unit, and a soldier from his platoon, Paul Read, told me that Burnett was a particularly formidable special operator, both physically commanding and a natural leader: “He was always super keen. He always wanted to be the best, even among the best.” (Another soldier recalled that Burnett was nicknamed the Male Model, because he was reluctant to “get any dirt under his fingernails.”) Burnett served in Northern Ireland, and then in the Falklands, where he took part in the 1982 advance on Port Stanley. The experience, he later said, was “horrific, but on the other hand—in a sick way—exciting.”

When Burnett left the Army, after five years, his plan was to find work in Central America as a “weapons and tactics adviser”—not as a mercenary, he later insisted, though it is difficult to parse the distinction. Before he left, his mother told him that she’d had a premonition and implored him not to take another job that involved carrying a gun. Like Trump, Burnett trusts his impulses. “Your gut instinct is rarely wrong,” he likes to say. During a layover in Los Angeles, he decided to heed his mother’s admonition, and walked out of the airport. He later described himself as the quintessential immigrant: “I had no money, no green card, no nothing.” But the California sun was shining, and he was eager to try his luck.

Burnett is an avid raconteur, and his anecdotes about his life tend to have a three-act structure. In Act I, he is a fish out of water, guileless and naïve, with nothing but the shirt on his back and an outsized dream. Act II is the rude awakening: the world bets against him. It’s impossible! You’ll lose everything! No such thing has ever been tried! In Act III, Burnett always prevails. Not long after arriving in California, he landed his first job—as a nanny. Eyebrows were raised: a commando turned nanny? Yet Burnett thrived, working for a family in Beverly Hills, then one in Malibu. As he later observed, the experience taught him “how nice the life styles of wealthy people are.” Young, handsome, and solicitous, he discovered that successful people are often happy to talk about their path to success.

Burnett married a California woman, Kym Gold, who came from an affluent family. “Mark has always been very, very hungry,” Gold told me recently. “He’s always had a lot of drive.” For a time, he worked for Gold’s stepfather, who owned a casting agency, and for Gold, who owned an apparel business. She would buy slightly imperfect T-shirts wholesale, at two dollars apiece, and Burnett would resell them, on the Venice boardwalk, for eighteen. That was where he learned “the art of selling,” he has said. The marriage lasted only a year, by which point Burnett had obtained a green card. (Gold, who had also learned a thing or two about selling, went on to co-found the denim company True Religion, which was eventually sold for eight hundred million dollars.)

One day in the early nineties, Burnett read an article about a new kind of athletic event: a long-distance endurance race, known as the Raid Gauloises, in which teams of athletes competed in a multiday trek over harsh terrain. In 1992, Burnett organized a team and participated in a race in Oman. Noticing that he and his teammates were “walking, climbing advertisements” for gear, he signed up sponsors. He also realized that if you filmed such a race it would make for exotic and gripping viewing. Burnett launched his own race, the Eco-Challenge, which was set in such scenic locations as Utah and British Columbia, and was televised on various outlets, including the Discovery Channel. Bienstock, who first met Burnett when he worked on the “Eco-Challenge” show, in 1996, told me that Burnett was less interested in the ravishing backdrops or in the competition than he was in the intense emotional experiences of the racers: “Mark saw the drama in real people being the driving force in an unscripted show.”

By this time, Burnett had met an aspiring actress from Long Island named Dianne Minerva and married her. They became consumed with making the show a success. “When we went to bed at night, we talked about it, when we woke up in the morning, we talked about it,” Dianne Burnett told me recently. In the small world of adventure racing, Mark developed a reputation as a slick and ambitious operator. “He’s like a rattlesnake,” one of his business competitors told the New York Times in 2000. “If you’re close enough long enough, you’re going to get bit.” Mark and Dianne were doing far better than Mark’s parents ever had, but he was restless. One day, they attended a seminar by the motivational speaker Tony Robbins called “Unleash the Power Within.” A good technique for realizing your goals, Robbins counselled, was to write down what you wanted most on index cards, then deposit them around your house, as constant reminders. In a 2012 memoir, “The Road to Reality,” Dianne Burnett recalls that she wrote the word “FAMILY” on her index cards. Mark wrote “MORE MONEY.”

As a young man, Burnett occasionally found himself on a flight for business, looking at the other passengers and daydreaming: If this plane were to crash on a desert island, where would I fit into our new society? Who would lead and who would follow? “Nature strips away the veneer we show one another every day, at which point people become who they really are,” Burnett once wrote. He has long espoused a Hobbesian world view, and when he launched “Survivor” a zero-sum ethos was integral to the show. “It’s quite a mean game, just like life is kind of a mean game,” Burnett told CNN, in 2001. “Everyone’s out for themselves.”

On “Survivor,” the competitors were split into teams, or “tribes.” In this raw arena, Burnett suggested, viewers could glimpse the cruel essence of human nature. It was undeniably compelling to watch contestants of different ages, body types, and dispositions negotiate the primordial challenges of making fire, securing shelter, and foraging for food. At the same time, the scenario was extravagantly contrived: the castaways were shadowed by camera crews, and helicopters thundered around the island, gathering aerial shots.

Moreover, the contestants had been selected for their charisma and their combustibility. “It’s all about casting,” Burnett once observed. “As a producer, my job is to make the choices in who to work with and put on camera.” He was always searching for someone with the sort of personality that could “break through the clutter.” In casting sessions, Burnett sometimes goaded people, to see how they responded to conflict. Katherine Walker, the “Apprentice” producer, told me about an audition in which Burnett taunted a prospective cast member by insinuating that he was secretly gay. (The man, riled, threw the accusation back at Burnett, and was not cast that season.)

Richard Levak, a clinical psychologist who consulted for Burnett on “Survivor” and “The Apprentice” and worked on other reality-TV shows, told me that producers have often liked people he was uncomfortable with for psychological reasons. Emotional volatility makes for compelling television. But recruiting individuals for their instability and then subjecting them to the stress of a televised competition can be perilous. When Burnett was once asked about Sinisa Savija’s suicide, he contended that Savija had “previous psychological problems.” No “Survivor” or “Apprentice” contestants are known to have killed themselves, but in the past two decades several dozen reality-TV participants have. Levak eventually stopped consulting on such programs, in part because he feared that a contestant might harm himself. “I would think, Geez, if this should unravel, they’re going to look at the personality profile and there may have been a red flag,” he recalled.

Burnett excelled at the casting equation to the point where, on Season 2 of “Survivor,” which was shot in the Australian outback, his castaways spent so much time gossiping about the characters from the previous season that Burnett warned them, “The more time you spend talking about the first ‘Survivor,’ the less time you will have on television.” But Burnett’s real genius was in marketing. When he made the rounds in L.A. to pitch “Survivor,” he vowed that it would become a cultural phenomenon, and he presented executives with a mock issue of Newsweek featuring the show on the cover. (Later, “Survivor” did make the cover of the magazine.) Burnett devised a dizzying array of lucrative product-integration deals. In the first season, one of the teams won a care package that was attached to a parachute bearing the red-and-white logo of Target.

“I looked on ‘Survivor’ as much as a marketing vehicle as a television show,” Burnett once explained. He was creating an immersive, cinematic entertainment—and he was known for lush production values, and for paying handsomely to retain top producers and editors—but he was anything but precious about his art. Long before he met Trump, Burnett had developed a Panglossian confidence in the power of branding. “I believe we’re going to see something like the Microsoft Grand Canyon National Park,” he told the New York Times in 2001. “The government won’t take care of all that—companies will.”

Seven weeks before the 2016 election, Burnett, in a smart tux with a shawl collar, arrived with his third wife, the actress and producer Roma Downey, at the Microsoft Theatre, in Los Angeles, for the Emmy Awards. Both “Shark Tank” and “The Voice” won awards that night. But his triumphant evening was marred when the master of ceremonies, Jimmy Kimmel, took an unexpected turn during his opening monologue. “Television brings people together, but television can also tear us apart,” Kimmel mused. “I mean, if it wasn’t for television, would Donald Trump be running for President?” In the crowd, there was laughter. “Many have asked, ‘Who is to blame for Donald Trump?’ ” Kimmel continued. “I’ll tell you who, because he’s sitting right there. That guy.” Kimmel pointed into the audience, and the live feed cut to a closeup of Burnett, whose expression resolved itself into a rigid grin. “Thanks to Mark Burnett, we don’t have to watch reality shows anymore, because we’re living in one,” Kimmel said. Burnett was still smiling, but Kimmel wasn’t. He went on, “I’m going on the record right now. He’s responsible. If Donald Trump gets elected and he builds that wall, the first person we’re throwing over it is Mark Burnett. The tribe has spoken.”

Around this time, Burnett stopped giving interviews about Trump or “The Apprentice.” He continues to speak to the press to promote his shows, but he declined an interview with me. Before Trump’s Presidential run, however, Burnett told and retold the story of how the show originated. When he met Trump at Wollman Rink, Burnett told him an anecdote about how, as a young man selling T-shirts on the boardwalk on Venice Beach, he had been handed a copy of “The Art of the Deal,” by a passing rollerblader. Burnett said that he had read it, and that it had changed his life; he thought, What a legend this guy Trump is!

Anyone else hearing this tale might have found it a bit calculated, if not implausible. Kym Gold, Burnett’s first wife, told me that she has no recollection of him reading Trump’s book in this period. “He liked mystery books,” she said. But when Trump heard the story he was flattered.

Burnett has never liked the phrase “reality television.” For a time, he valiantly campaigned to rebrand his genre “dramality”—“a mixture of drama and reality.” The term never caught on, but it reflected Burnett’s forthright acknowledgment that what he creates is a highly structured, selective, and manipulated rendition of reality. Burnett has often boasted that, for each televised hour of “The Apprentice,” his crews shot as many as three hundred hours of footage. The real alchemy of reality television is the editing—sifting through a compost heap of clips and piecing together an absorbing story. Jonathon Braun, an editor who started working with Burnett on “Survivor” and then worked on the first six seasons of “The Apprentice,” told me, “You don’t make anything up. But you accentuate things that you see as themes.” He readily conceded how distorting this process can be. Much of reality TV consists of reaction shots: one participant says something outrageous, and the camera cuts away to another participant rolling her eyes. Often, Braun said, editors lift an eye roll from an entirely different part of the conversation.

“The Apprentice” was built around a weekly series of business challenges. At the end of each episode, Trump determined which competitor should be “fired.” But, as Braun explained, Trump was frequently unprepared for these sessions, with little grasp of who had performed well. Sometimes a candidate distinguished herself during the contest only to get fired, on a whim, by Trump. When this happened, Braun said, the editors were often obliged to “reverse engineer” the episode, scouring hundreds of hours of footage to emphasize the few moments when the exemplary candidate might have slipped up, in an attempt to assemble an artificial version of history in which Trump’s shoot-from-the-hip decision made sense. During the making of “The Apprentice,” Burnett conceded that the stories were constructed in this way, saying, “We know each week who has been fired, and, therefore, you’re editing in reverse.” Braun noted that President Trump’s staff seems to have been similarly forced to learn the art of retroactive narrative construction, adding, “I find it strangely validating to hear that they’re doing the same thing in the White House.”

Such sleight of hand is the industry standard in reality television. But the entire premise of “The Apprentice” was also something of a con. When Trump and Burnett told the story of their partnership, both suggested that Trump was initially wary of committing to a TV show, because he was so busy running his flourishing real-estate empire. During a 2004 panel at the Museum of Television and Radio, in Los Angeles, Trump claimed that “every network” had tried to get him to do a reality show, but he wasn’t interested: “I don’t want to have cameras all over my office, dealing with contractors, politicians, mobsters, and everyone else I have to deal with in my business. You know, mobsters don’t like, as they’re talking to me, having cameras all over the room. It would play well on television, but it doesn’t play well with them.”

“The Apprentice” portrayed Trump not as a skeezy hustler who huddles with local mobsters but as a plutocrat with impeccable business instincts and unparalleled wealth—a titan who always seemed to be climbing out of helicopters or into limousines. “Most of us knew he was a fake,” Braun told me. “He had just gone through I don’t know how many bankruptcies. But we made him out to be the most important person in the world. It was like making the court jester the king.” Bill Pruitt, another producer, recalled, “We walked through the offices and saw chipped furniture. We saw a crumbling empire at every turn. Our job was to make it seem otherwise.”

Trump maximized his profits from the start. When producers were searching for office space in which to stage the show, he vetoed every suggestion, then mentioned that he had an empty floor available in Trump Tower, which he could lease at a reasonable price. (After becoming President, he offered a similar arrangement to the Secret Service.) When the production staff tried to furnish the space, they found that local venders, stiffed by Trump in the past, refused to do business with them.

More than two hundred thousand people applied for one of the sixteen spots on Season 1, and throughout the show’s early years the candidates were conspicuously credentialled and impressive. Officially, the grand prize was what the show described as “the dream job of a lifetime”—the unfathomable privilege of being mentored by Donald Trump while working as a junior executive at the Trump Organization. All the candidates paid lip service to the notion that Trump was a peerless businessman, but not all of them believed it. A standout contestant in Season 1 was Kwame Jackson, a young African-American man with an M.B.A. from Harvard, who had worked at Goldman Sachs. Jackson told me that he did the show not out of any desire for Trump’s tutelage but because he regarded the prospect of a nationally televised business competition as “a great platform” for career advancement. “At Goldman, I was in private-wealth management, so Trump was not, by any stretch, the most financially successful person I’d ever met or managed,” Jackson told me. He was quietly amused when other contestants swooned over Trump’s deal-making prowess or his elevated tastes—when they exclaimed, on tours of tacky Trump properties, “Oh, my God, this is so rich—this is, like, really rich!” Fran Lebowitz once remarked that Trump is “a poor person’s idea of a rich person,” and Jackson was struck, when the show aired, by the extent to which Americans fell for the ruse. “Main Street America saw all those glittery things, the helicopter and the gold-plated sinks, and saw the most successful person in the universe,” he recalled. “The people I knew in the world of high finance understood that it was all a joke.”

This is an oddly common refrain among people who were involved in “The Apprentice”: that the show was camp, and that the image of Trump as an avatar of prosperity was delivered with a wink. Somehow, this interpretation eluded the audience. Jonathon Braun marvelled, “People started taking it seriously!”

When I watched several dozen episodes of the show recently, I saw no hint of deliberate irony. Admittedly, it is laughable to hear the candidates, at a fancy meal, talk about watching Trump for cues on which utensil they should use for each course, as if he were Emily Post. But the show’s reverence for its pugnacious host, however credulous it might seem now, comes across as sincere.

Did Burnett believe what he was selling? Or was Trump another two-dollar T-shirt that he pawned off for eighteen? It’s difficult to say. One person who has collaborated with Burnett likened him to Harold Hill, the travelling fraudster in “The Music Man,” saying, “There’s always an angle with Mark. He’s all about selling.” Burnett is fluent in the jargon of self-help, and he has published two memoirs, both written with Bill O’Reilly’s ghostwriter, which double as manuals on how to get rich. One of them, titled “Jump In!: Even if You Don’t Know How to Swim,” now reads like an inadvertent metaphor for the Trump Presidency. “Don’t waste time on overpreparation,” the book advises.

At the 2004 panel, Burnett made it clear that, with “The Apprentice,” he was selling an archetype. “Donald is the real current-day version of a tycoon,” he said. “Donald will say whatever Donald wants to say. He takes no prisoners. If you’re Donald’s friend, he’ll defend you all day long. If you’re not, he’s going to kill you. And that’s very American. It’s like the guys who built the West.” Like Trump, Burnett seemed to have both a jaundiced impression of the gullible essence of the American people and a brazen enthusiasm for how to exploit it. “The Apprentice” was about “what makes America great,” Burnett said. “Everybody wants one of a few things in this country. They’re willing to pay to lose weight. They’re willing to pay to grow hair. They’re willing to pay to have sex. And they’re willing to pay to learn how to get rich.”

At the start of “The Apprentice,” Burnett’s intention may have been to tell a more honest story, one that acknowledged Trump’s many stumbles. Burnett surely recognized that Trump was at a low point, but, according to Walker, “Mark sensed Trump’s potential for a comeback.” Indeed, in a voice-over introduction in the show’s pilot, Trump conceded a degree of weakness that feels shockingly self-aware when you listen to it today: “I was seriously in trouble. I was billions of dollars in debt. But I fought back, and I won, big league.”

The show was an instant hit, and Trump’s public image, and the man himself, began to change. Not long after the première, Trump suggested in an Esquire article that people now liked him, “whereas before, they viewed me as a bit of an ogre.” Jim Dowd, Trump’s former publicist, told Michael Kranish and Marc Fisher, the authors of the 2016 book “Trump Revealed,” that after “The Apprentice” began airing “people on the street embraced him.” Dowd noted, “All of a sudden, there was none of the old mocking,” adding, “He was a hero.” Dowd, who died in 2016, pinpointed the public’s embrace of “The Apprentice” as “the bridge” to Trump’s Presidential run.

The show’s camera operators often shot Trump from low angles, as you would a basketball pro, or Mt. Rushmore. Trump loomed over the viewer, his face in a jowly glower, his hair darker than it is now, the metallic auburn of a new penny. (“Apprentice” employees were instructed not to fiddle with Trump’s hair, which he dyed and styled himself.) Trump’s entrances were choreographed for maximum impact, and often set to a moody accompaniment of synthesized drums and cymbals. The “boardroom”—a stage set where Trump determined which candidate should be fired—had the menacing gloom of a “Godfather” movie. In one scene, Trump ushered contestants through his rococo Trump Tower aerie, and said, “I show this apartment to very few people. Presidents. Kings.” In the tabloid ecosystem in which he had long languished, Trump was always Donald, or the Donald. On “The Apprentice,” he finally became Mr. Trump.

“We have to subscribe to our own myths,” the “Apprentice” producer Bill Pruitt told me. “Mark Burnett is a great mythmaker. He blew up that balloon and he believed in it.” Burnett, preferring to spend time pitching new ideas for shows, delegated most of the daily decisions about “The Apprentice” to his team, many of them veterans of “Survivor” and “Eco-Challenge.” But he furiously promoted the show, often with Trump at his side. According to many of Burnett’s collaborators, one of his greatest skills is his handling of talent—understanding their desires and anxieties, making them feel protected and secure. On interview tours with Trump, Burnett exhibited the studied instincts of a veteran producer: anytime the spotlight strayed in his direction, he subtly redirected it at Trump.

Burnett, who was forty-three when Season 1 aired, described the fifty-seven-year-old Trump as his “soul mate.” He expressed astonishment at Trump’s “laser-like focus and retention.” He delivered flattery in the ostentatiously obsequious register that Trump prefers. Burnett said he hoped that he might someday rise to Trump’s “level” of prestige and success, adding, “I don’t know if I’ll ever make it. But you know something? If you’re not shooting for the stars, you’re not shooting!” On one occasion, Trump invited Burnett to dinner at his Trump Tower apartment; Burnett had anticipated an elegant meal, and, according to an associate, concealed his surprise when Trump handed him a burger from McDonald’s.

Trump liked to suggest that he and Burnett had come up with the show “together”; Burnett never corrected him. When Carolyn Kepcher, a Trump Organization executive who appeared alongside Trump in early seasons of “The Apprentice,” seemed to be courting her own celebrity, Trump fired her and gave on-air roles to three of his children, Ivanka, Donald, Jr., and Eric. Burnett grasped that the best way to keep Trump satisfied was to insure that he never felt upstaged. “It’s Batman and Robin, and I’m clearly Robin,” he said.

Burnett sometimes went so far as to imply that Trump’s involvement in “The Apprentice” was a form of altruism. “This is Donald Trump giving back,” he told the Times in 2003, then offered a vague invocation of post-9/11 civic duty: “What makes the world a safe place right now? I think it’s American dollars, which come from taxes, which come because of Donald Trump.” Trump himself had been candid about his reasons for doing the show. “My jet’s going to be in every episode,” he told Jim Dowd, adding that the production would be “great for my brand.”

It was. Season 1 of “The Apprentice” flogged one Trump property after another. The contestants stayed at Trump Tower, did events at Trump National Golf Club, sold Trump Ice bottled water. “I’ve always felt that the Trump Taj Mahal should do even better,” Trump announced before sending the contestants off on a challenge to lure gamblers to his Atlantic City casino, which soon went bankrupt. The prize for the winning team was an opportunity to stay and gamble at the Taj, trailed by cameras.

“The Apprentice” was so successful that, by the time the second season launched, Trump’s lacklustre tie-in products were being edged out by blue-chip companies willing to pay handsomely to have their wares featured onscreen. In 2004, Kevin Harris, a producer who helped Burnett secure product-integration deals, sent an e-mail describing a teaser reel of Trump endorsements that would be used to attract clients: “Fast cutting of Donald—‘Crest is the biggest’ ‘I have worn Levis since I was 2’ ‘I love M&Ms’ ‘Unilever is the biggest company in the world’ all with the MONEY MONEY MONEY song over the top.”

Burnett and Trump negotiated with NBC to retain the rights to income derived from product integration, and split the fees. On set, Trump often gloated about this easy money. One producer remembered, “You’d say, ‘Hey, Donald, today we have Pepsi, and they’re paying three million to be in the show,’ and he’d say, ‘That’s great, I just made a million five!’ ”

Originally, Burnett had planned to cast a different mogul in the role of host each season. But Trump took to his part more nimbly than anyone might have predicted. He wouldn’t read a script—he stumbled over the words and got the enunciation all wrong. But off the cuff he delivered the kind of zesty banter that is the lifeblood of reality television. He barked at one contestant, “Sam, you’re sort of a disaster. Don’t take offense, but everyone hates you.” Katherine Walker told me that producers often struggled to make Trump seem coherent, editing out garbled syntax and malapropisms. “We cleaned it up so that he was his best self,” she said, adding, “I’m sure Donald thinks that he was never edited.” However, she acknowledged, he was a natural for the medium: whereas reality-TV producers generally must amp up personalities and events, to accentuate conflict and conjure intrigue, “we didn’t have to change him—he gave us stuff to work with.” Trump improvised the tagline for which “The Apprentice” became famous: “You’re fired.”

NBC executives were so enamored of their new star that they instructed Burnett and his producers to give Trump more screen time. This is when Trump’s obsession with television ratings took hold. “I didn’t know what demographics was four weeks ago,” he told Larry King. “All of a sudden, I heard we were No. 3 in demographics. Last night, we were No. 1 in demographics. And that’s the important rating.” The ratings kept rising, and the first season’s finale was the No. 1 show of the week. For Burnett, Trump’s rehabilitation was a satisfying confirmation of a populist aesthetic. “I like it when critics slam a movie and it does massive box office,” he once said. “I love it.” Whereas others had seen in Trump only a tattered celebrity of the eighties, Burnett had glimpsed a feral charisma.

On June 26, 2018, the day the Supreme Court upheld President Trump’s travel ban targeting people from several predominantly Muslim countries, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo sent out invitations to an event called a Ministerial to Advance Religious Freedom. If Pompeo registered any dissonance between such lofty rhetoric and Administration policies targeting certain religions, he didn’t mention it.

The event took place the next month, at the State Department, in Washington, D.C., and one of the featured speakers was Mark Burnett. In 2004, he had been getting his hair cut at a salon in Malibu when he noticed an attractive woman getting a pedicure. It was Roma Downey, the star of “Touched by an Angel,” a long-running inspirational drama on CBS. They fell in love, and married in 2007; together, they helped rear Burnett’s two sons from his second marriage and Downey’s daughter. Downey, who grew up in a Catholic family in Northern Ireland, is deeply religious, and eventually Burnett, too, reoriented his life around Christianity. “Faith is a major part of our marriage,” Downey said, in 2013, adding, “We pray together.”

For people who had long known Burnett, it was an unexpected turn. This was a man who had ended his second marriage during a live interview with Howard Stern. To promote “Survivor” in 2002, Burnett called in to Stern’s radio show, and Stern asked casually if he was married. When Burnett hesitated, Stern pounced. “You didn’t survive marriage?” he asked. “You don’t want your girlfriend to know you’re married?” As Burnett dissembled, Stern kept prying, and the exchange became excruciating. Finally, Stern asked if Burnett was “a single guy,” and Burnett replied, “You know? Yeah.” This was news to Dianne, Burnett’s wife of a decade. As she subsequently wrote in her memoir, “The 18-to-34 radio demographic knew where my marriage was headed before I did.”

In 2008, Burnett’s longtime business partner, a lawyer named Conrad Riggs, filed a lawsuit alleging that Burnett had stiffed him to the tune of tens of millions of dollars. According to the lawsuit, the two men had made an agreement before “Survivor” and “The Apprentice” that Riggs would own ten per cent of Burnett’s company. When Riggs got married, someone who attended the ceremony told me, Burnett was his best man, and gave a speech saying that his success would have been impossible without Riggs. Several years later, when Burnett’s company was worth half a billion dollars, he denied having made any agreement. The suit settled out of court. (Riggs declined to comment.)

Article from January 7, 2019 By Patrick Radden Keefe

Yobaba - New Yorker mag articles are LONG; I posted this mostly for my own reference so I will have a record of it; that said, I strongly urge everyone to read this. it explains a lot.

2 notes

·

View notes