#many of these revelations simply could not have been interpreted correctly without the light of modern methods

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Bird-reptiles is a butterfly-moth situation?

Precisely! These kinds of situations show us how wrong we have been for so long about the relationships among various animals. The pretty little boxes we like to make are often very, very wrong, phylogenetically, i.e., they are not compatible with the *actual* relationships among the organisms.

Here are a few other mind-fucks that have come to light as a result of modern methods being applied to traditional categories that turned out to be wrong:

• Snakes are lizards

• Termites are cockroaches

• Birds belong to lizard-hipped dinosaurs (Saurischia), not the bird-hipped ones (Ornithischia)

• All tetrapods are fish

• Insects are crustaceans

#the more you know#science#phylogeny#taxonomy#I find these kinds of situations hilarious#but also beautiful#they show us just how much we have learned over the last few centuries#many of these revelations simply could not have been interpreted correctly without the light of modern methods#and I think that's beautiful#Who knows what kinds of additional mindfucks await us#Answers by Mark

1K notes

·

View notes

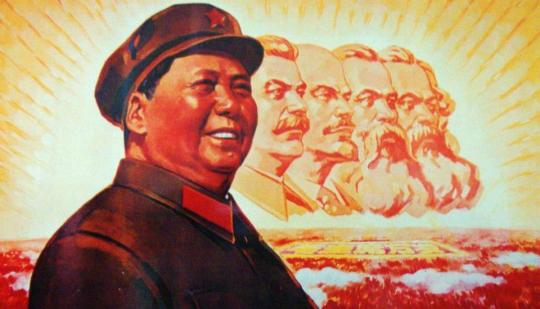

Photo

From ‘The History of USSR-China Relations’ by Vince Copeland

The carefully hidden differences between the Chinese CP and Stalin first came to light in 1956 and 1957, three or four years after Stalin's death. In one of the first public revelations of this, the Chinese said:

"Stalin displayed certain great-nation chauvinist tendencies in relation to brother parties and countries. The essence of such tendencies lies in being unmindful of the independent and equal status of the communist parties of various lands and that of the socialist countries."[1]

In light of the subsequent Chinese repudiation of Khrushchev and reestablishment of Stalin, these powerful words from the Chinese are worth some study. It would appear that Stalin, the author of "Marxism and the National Question," violated the spirit of his own youthful essay, and so much so that the Chinese repeated this criticism several times after his death.

The point, however, is not so much the role of Stalin in particular as it is the question of great-nation chauvinism in general. Every word of the above quotation burns with repressed anger against arrogant treatment and violations of the "independent and equal status" of the persons who wrote it. The fact that it does not specifically mention the experiences of the Chinese themselves is all the more eloquent. How many times more sharply the Chinese must have felt these things considering that they had been members of an oppressed nation and accustomed to the contemptuous treatment of the British and American imperialists over decades and generations!

This charge of great-nation chauvinism runs like a red thread through all the subsequent arguments with Khrushchev, and Brezhnev, too, even when the actual words are not mentioned. The accusation against Stalin arises not from a casual remembrance but from a still burning sense of injustice in the old relationship now projected into the new one.

To show that this great-nation arrogance among the leaders of the Soviet CP had existed for a very long time, let us go back to the year 1922. It was Stalin's idea at that time that all the formerly oppressed nations within the territory of what was once Czarist Russia should simply join the already existing Russian Socialist Federation of Soviet Republics (RSFSR) after the civil war on the principle of autonomy for each.

Lenin strongly objected to this and proposed:

"We recognize ourselves as equal with the Ukrainian Republic and the others, and join the new union, the new federation, together with them and on equal footing."[2]

In accordance with Lenin's advice, the draft was changed, the first congress of the various nations was held on December 30, 1922, and the new Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was founded in equal comradeship by the Russian and non-Russian nations together.

Lenin warns about 'the Russian frame of mind'

About the same time, Lenin bitterly denounced Stalin's narrowness on the national question, particularly in respect to Georgia, Stalin's own homeland:

"I also fear that Comrade Dzerzhinsky, who went to the Caucasus to investigate the crime of those nationalist-socialists distinguished himself there by his truly Russian frame of mind [it is common knowledge that people of other nationalities who have become Russified overdo the Russian frame of mind]." [3]

After severely criticizing another of Stalin's close collaborators, Orjonikidze, for actual brutality on the scene in Georgia and recommending "suitable punishment" for him, Lenin continues:

"The political responsibility for all this truly Great-Russian campaign must, of course, be laid on Stalin and Dzerzhinsky."[4]

And concluding with prophetic clarity about future relations with China, he writes:

"It would be unpardonable opportunism if, on the eve of the debut of the East, just as it is awakening, we undermine our prestige with its peoples, even if only by the slightest crudity or injustice towards our own non-Russian nationalities. The need to rally against the imperialists of the West ... is one thing ... It is another thing when we ourselves lapse, even if only in trifles, into imperialist attitudes towards oppressed nationalities, thus undermining all our principled sincerity, all our principled defense of the struggle against imperialism." [5]

In this short passage Lenin pinpoints not just the uncommunist Great-Russian chauvinism of Stalin, but also the chauvinist failings of a number of others — Lenin's diplomatically designated "we ourselves" — who were to inherit the Soviet Party along with Stalin.

To those who are used to thinking of socialist countries as utopias rather than as historical advances of the working class which still bear the birthmarks from the tortured capitalist past, Stalin's defects and these sharp words of Lenin may be somewhat of a letdown. But even if Lenin's criticism had been twice as sharp, this would not have indicated that the revolution-based USSR was actually imperialist, in spite of the uncommunist "imperialist attitudes" of some of its leaders.

The USSR, like the People's Republic of China and other socialist countries, is not the political expression of a group of individual leaders, but an objective complex of concrete social institutions that emerged from the revolutionary action of millions of people. These millions were under the leadership of a Marxist party, to be sure, but they physically smashed not only the old ruling class, but also its armies, prisons, courts, and property relations. This being the case, a number of "bad" leaders could later put a braking effect upon the full benefits of the new social institutions, including the effect of social backwardness on many questions. But they could not by a mere act of political will turn these institutions back into their opposite, that is, capitalist, imperialist institutions. ...

Let us take the case of Stalin himself. His interference with the Chinese CP at an earlier date did not arise so much from innate feelings of superiority as from caution about breaking the defense treaty (against Japan) with the still powerful Chiang Kai-shek. But the Chinese now interpret this first and foremost as "great-nation chauvinism." And this chauvinism was undoubtedly a factor in Stalin's attitude, since he continually put his judgment about the Chinese revolution (which happened to be wrong anyway) ahead of theirs and imposed it on them. ...

The inequalities in Stalin's time were far more advanced than in the time of Lenin, who had already said, "What we really have is a workers' state with bureaucratic distortions." [6] Stalin still further emphasized the imperialist attitude, however unconsciously, because of his lack of faith in the Chinese revolution.

Khrushchev, and later Brezhnev, merely carried this position still further to the right, although with some oscillations to the left. With all three leaders it was in varying degrees a combination of national chauvinism and fear of the power of imperialism while they still governed a country whose advanced, dynamic social system had been established by the greatest revolution in human history.

Thus the Soviet leaders under Stalin at first provided little help for the Chinese CP in the crucial civil war of 1945-1949, [7] partly because they had no faith that it would succeed [8] and partly because they feared the consequences of success (such as a new war). But great-nation chauvinism was also an element in their lack of faith. The Chinese carefully noted Stalin's consideration for Roosevelt and Churchill during World War II and saw that he continued to ally himself with the U.S. puppet Chiang Kai-shek long after their own civil war against Chiang had begun. ...

Chinese CP refuses to give up its arms

In 1945 and 1946, when Chiang proposed (at U.S. prompting) that the Chinese CP join with the bourgeois Kuomintang in a coalition government, Stalin and the Soviet leadership went along with the idea. But it was undoubtedly the Chinese CP that decided to accept the coalition only on the condition that the Communist Red Army keep its weapons and remain intact. [11]

When Chiang refused to agree with this condition, he touched off a civil war — at first somewhat to the surprise and concern of Stalin and the other Soviet leaders.

The Soviet leaders had calculated that Chiang would rule China for a long period after the defeat of imperialist Japan, and Stalin accordingly made agreements with Chiang (as against Japan) at the post-war Potsdam Conference without necessarily consulting the Chinese CP. And of course Stalin recognized the Chiang government as the exclusive representative of China at the formation of the United Nations after the war, even though he was well aware that the Chinese CP already controlled hundreds of thousands of square miles of China and had the allegiance of millions of people.

Stalin apparently thought the fighting was over after eight years of war with Japan. He apparently thought that the Chinese CP would give up its arms and enter the bourgeois government as a "loyal opposition," just as the French and Italian CPs had done.

This did not prevent him from welcoming the victorious Chinese revolution into the Soviet bloc four years later in the middle of the Cold War, in spite of the problems it created for him. Similarly, Khrushchev welcomed the Cuban revolution, although he had a general policy of accommodation with the U.S. — incidentally proving as Stalin did that a non-revolutionary policy does not prove there is a non-revolutionary state.

In addition to all the problems the Chinese CP had with Chiang Kai-shek, they had many with the leaders of the first workers' state. They might have correctly criticized the Soviet leadership for its conduct during the Chinese revolution, while making sure to underline the working class character of the USSR. But in the context of the Cold War such an approach could have been interpreted as a blow against the foundations as well as the superstructure of the USSR. Such a line might have isolated the revolution and the infant revolutionary Chinese state and left it open to penetration by the imperialist United States.

But nevertheless, relations between the two parties were difficult. [12] It was not until after the Chinese CP took power, and even then, not until Mao's trip to the Soviet Union late in December 1949, that relations between the two national parties were really good. [13] (It is noteworthy that this was Mao's first trip to Moscow, while his old opponents in the Chinese CP had gone there again and again, mainly to get support against him.) [14]

There was much imperialist speculation about a break between the two parties — and countries — during the weeks that Mao was in the Soviet Union (December 1949-February 1950) negotiating a treaty with Stalin. And there was a feverish intrigue of U.S. agents in Hong Kong and other places to prevent an agreement from taking place at all.

#China#Chinese Revolution#Stalin#USSR#national chauvinism#workers state#socialism#communist#revolution#Marxism#Lenin#Mao#armed struggle#imperialism#reformism#peaceful coexistence#Stalinism#Vince Copeland

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

MARY THE CHURCH AT THE SOURCE - PART 2

WRITTEN BY: JOSEPH CARDINAL RATZINGER AND HANS URS VON BALTHASAR

________

II

THOUGHTS ON THE PLACE OF MARIAN DOCTRINE AND PIETY IN FAITH AND THEOLOGY AS A WHOLE

I. The Background and Significance of the Second Vatican Council’s Declarations on Mariology

The question of the significance of Marian doctrine and piety cannot disregard the historical situation of the Church in which the question arises. We can understand and respond correctly to the profound crisis of postconciliar Marian doctrine and devotion only if we see this crisis in the context of the larger development of which it is a part. Now, we can say that two major spiritual movements defined the period stretching from the end of the First World War to the Second Vatican Council, two movements that had—albeit in very different ways—certain “charismatic features”. On the one side, there was a Marian movement that could claim charismatic roots in La Salette, Lourdes, and Fatima. It had steadily grown in vigor since the Marian apparitions of the mid-1800s. By the time it reached its peak under Pius XII, its influence had spread throughout the whole Church. On the other side, the interwar years had seen the development of the liturgical movement, especially in Germany, the origins of which can be traced to the renewal of Benedictine monasticism emanating from Solesmes as well as to the eucharistic inspiration of Pius X. Against the background of the youth movement, it gained—in Central Europe, at least—an increasingly wider influence throughout the Church at large. The ecumenical and biblical movements quickly joined with it to form a single mighty stream. Its fundamental goal—the renewal of the Church from the sources of Scripture and the primitive form of the Church’s prayer—likewise received its first official confirmation under Pius XII in his encyclicals on the Church and on the liturgy.1

As these movements increasingly influenced the universal Church, the problem of their mutual relationship also came increasingly to the fore. In many respects, they seemed to embody opposing attitudes and theological orientations. The liturgical movement tended to characterize its own piety as “objective” and sacramental, to which the strong emphasis on the subjective and personal in the Marian movement offered a striking contrast. The liturgical movement stressed the theocentric character of Christian prayer, which is addressed “through Christ to the Father”; the Marian movement, with its slogan per Mariam àd Jesum [through Mary to Jesus], seemed characterized by a different idea of mediation, by a kind of lingering with Jesus and Mary that pushed the classical trinitarian reference into the background. The liturgical movement sought a piety governed strictly by the measure of the Bible or, at the most, of the ancient Church; the Marian piety that responded to the modern apparitions of the Mother of God was much more heavily influenced by traditions stemming from the Middle Ages and modernity. It reflected another style of thought and feeling.2 The Marian movement doubtless carried with it certain risks that threatened its own basic core (which was healthy) and even made it appear dubious to passionate champions of the other school of thought.3

In any case, a council held at that time could hardly avoid the task of working out the correct relationship between these two divergent movements and of bringing them into a fruitful unity—without simply eliminating their tension. In fact, we can understand correctly the struggles that marked the first half of the Council—the disputes surrounding the Constitution on the Liturgy, the doctrine of the Church, and the right integration of Mariology into ecclesiology, the debate about revelation, Scripture, tradition, and ecumenism—only in light of the tension between these two forces. All the debates we have just mentioned turned—even when there was no explicit awareness of this fact—on the struggle to hammer out the right relationship between the two charismatic currents that were, so to say, the domestic “signs of the times” for the Church. The elaboration of the Pastoral Constitution would then provide the occasion for dealing with the “signs of the times” pressing upon the Church from outside. In this drama the famous vote of October 29, 1963, marked an intellectual watershed. The question at issue was whether to present Mariology in a separate text or to incorporate it into the Constitution on the Church. In other words, the Fathers had to decide the weight and relative ordering of the two schools of piety and thus to give the decisive answer to the situation then existing within the Church. Both sides dispatched men of the highest caliber to win over the plenum. Cardinal König advocated integrating the texts, which de facto could only mean assigning priority to liturgical-biblical piety. Cardinal Rufino Santos of Manila, on the other hand, made the case for the independence of the Marian element. The result of the voting—1114 to 1074—showed for the first time that the assembly was divided into two almost equally large groups. Nevertheless, the part of the Council Fathers shaped by the biblical and liturgical movements had won a victory—albeit a narrow one—and thus brought about a decision whose significance can hardly be overestimated.

Theologically speaking, the majority spearheaded by Cardinal Konig was right. If the two charismatic movements should not be seen as contrary, but must be regarded as complementary, then an integration was imperative, even though this integration could not mean the absorption of one movement by the other. After the Second World War, Hugo Rahner,4 A. Muller,5 K. Delahaye,6 R. Laurentin,7 and O. Semmelroth8 had convincingly demonstrated the intrinsic openness of biblical-liturgical-patristic piety to the Marian dimension. These authors succeeded in deepening both trends toward their center, in which they could meet and from which they could still preserve and fruitfully develop their distinctive character. As the facts stand, however, the Marian chapter of Lumen Gentium was only partly successful in persuasively and vigorously fleshing out the proposal these authors had outlined. Furthermore, postconciliar developments were shaped to a large extent by a misunderstanding of what the Council had actually said about the concept of tradition; this misunderstanding was given a crucial boost by the simplistic reporting of the conciliar debates in the media coverage. The whole debate was reduced to Geiselmann’s question concerning the material “sufficiency” of Scripture,9 which in turn was interpreted in the sense of a biblicism that condemned the whole patristic heritage to irrelevance and thereby also undermined what had until then been the point of the liturgical movement itself. Given the contemporary academic situation, however, biblicism automatically became historicism. Admittedly, even the liturgical movement itself had not been wholly free from historicism. Rereading its literature today, one finds that it was much too influenced by an archeological mentality that presupposed a model of decline: What occurs after a certain point in time appears ipso facto to be of inferior value, as if the Church were not alive and therefore capable of development in every age. As a result of all this, the kind of thinking shaped by the liturgical movement narrowed into a biblicist-positivist mentality, locked itself into a backward-looking attitude, and thus left no more room for the dynamic development of the faith. On the other hand, the distance implied in historicism inevitably paved the way for “modernism”; since what is merely past is no longer living, it leaves the present isolated and so leads to self-made experimentation. An additional factor was that the new, ecclesiocentric Mariology was foreign, and to a large extent remained foreign, precisely to those Council Fathers who had been the principal upholders of Marian piety. Nor could the vacuum thus produced be filled in by Paul VI’s introduction of the title “Mother of the Church” at the end of the Council, which was a conscious attempt to answer the crisis that was already looming on the horizon. In fact, the immediate outcome of the victory of ecclesio centric Mariology was the collapse of Mariology altogether. It seems to me that the changed look of the Church in Latin America after the Council, the occasional concentration of religious feeling on political change, must be understood against the background of these events.

2. The Positive Function of Mariology in Theology

A rethinking was set in motion above all by Paul VI’s apostolic letter Marialis Cultus (February 2, 1974) on the right form of Marian veneration. As we saw, the decision of 1963 had led de facto to the absorption of Mariology by ecclesiology. A reconsideration of the text has to begin with the recognition that its actual historical effect contradicts its own original meaning. For the chapter on Mary (chap. 8) was written so as to correspond intrinsically to chapters 1-4, which describe the structure of the Church. The balance of the two was meant to secure the correct equilibrium that would fruitfully correlate the respective energies of the biblical-ecumenical-liturgical movement and the Marian movements. Let us put it positively: Mariology, rightly understood, clarifies and deepens the concept of Church in two ways.

a. In contrast to the masculine, activistic-sociological populus Dei (people of God) approach, Church10—ecclesia— is feminine. This fact opens a dimension of the mystery that points beyond sociology, a dimension wherein the real ground and unifying power of the reality Church first appears. Church is more than “people”, more than structure and action: the Church contains the living mystery of maternity and of the bridal love that makes maternity possible. There can be ecclesial piety, love for the Church, only if this mystery exists. When the Church is no longer seen in any but a masculine, structural, purely theoretical way, what is most authentically ecclesial about ecclesia has been ignored-the center upon which the whole of biblical and patristic talk about the Church actually hinges.11

b. Paul captures the differentia specifica [specific difference] of the New Testament Church with respect to the Old Testament “pilgrim people of God” in the term “Body of Christ”. Church is, not an organization, but an organism of Christ. If Church becomes a “people” at all, it is only through the mediation of Christology. This mediation, in turn, happens in the sacraments, in the Eucharist, which for its part presupposes the Cross and Resurrection as the condition of its possibility. Consequently, one is not talking about the Church if one says “people of God” without at the same time saying, or at least thinking, “Body of Christ”.12 But even the concept of the Body of Christ needs clarification in order not to be misunderstood in today’s context: it could easily be interpreted in the sense of a Christomonism, of an absorption of the Church, and thus of the believing creature, into the uniqueness of Christology. In Pauline terms, however, the claim that we are the “Body of Christ” makes sense only against the backdrop of the formula of Genesis 2:24: “The two shall become one flesh” (cf. 1 Cor 6:17). The Church is the body, the flesh of Christ in the spiritual tension of love wherein the spousal mystery of Adam and Eve is consummated, hence, in the dynamism of a unity that does not abolish dialogical reciprocity [Gegenübersein]. By the same token, precisely the eucharistic-christological mystery of the Church indicated in the term “Body of Christ” remains within the proper measure only when it includes the mystery of Mary: the mystery of the listening handmaid who—liberated in grace—speaks her Fiat and, in so doing, becomes bride and thus body.13

If this is the case, then Mariology can never simply be dissolved into an impersonal ecclesiology. It is a thorough misunderstanding of patristic typology to reduce Mary to a mere, hence, interchangeable, exemplification of theological structures. Rather, the type remains true to its meaning only when the noninterchangeable personal figure of Mary becomes transparent to the personal form of the Church herself. In theology, it is not the person that is reducible to the thing, but the thing to the person. A purely structural ecclesiology is bound to degrade Church to the level of a program of action. Only the Marian dimension secures the place of affectivity in faith and thus ensures a fully human correspondence to the reality of the incarnate Logos. Here I see the truth of the saying that Mary is the “vanquisher of all heresies”. This affective rooting guarantees the bond ex toto corde-from the depth of the heart—to the personal God and his Christ and rules out any recasting of Christology into a Jesus program, which can be atheistic and purely neutral: the experience of the last few years verifies today in an astonishing way the accuracy of such ancient phrases.

3. The Place of Mariology in the Whole of Theology

In the light of what has been said, the place of Mariology in theology also becomes clear. In his massive tome on the history of Marian doctrine, G. Soil, summing up his historical analysis, defends the correlation of Mariology with Christology and soteriology against ecclesiological approaches to Marian doctrine.14 Without diminishing the extraordinary achievement of this work or the import of its historical findings, I take an opposite view. In my opinion, the Council Fathers’ option for a different approach was correct—correct from the point of view of dogmatic theology and of larger historical considerations. Soil’s conclusions about the history of dogma are, of course, beyond dispute: Propositions about Mary first became necessary in function of Christology and developed as part of the structure of Christology. We must add, however, that none of the affirmations made in this context did or could constitute an independent Mariology; rather, they remained an explication of Christology. By contrast, the patristic period foreshadowed the whole of Mariology in the guise of ecclesiology, albeit without any mention of the name of the Mother of the Lord: The virgo ecclesia [virgin Church], the mater ecclesia [mother Church], the ecclesia immaculata [immaculate Church], the ecclesia assumpta [assumed Church]—the whole content of what would later become Mariology was first conceived as ecclesiology. To be sure, ecclesiology itself cannot be isolated from Christology. Nevertheless, the Church has a relative subsistence [Selbstandigkeit] vis-à-vis Christ, as we saw just now: the subsistence of the bride who, even when she becomes one flesh with Christ in love, nonetheless remains an other before him. [Gegenüber].

It was not until this initially anonymous, though personally shaped, ecclesiology fused with the dogmatic propositions about Mary prepared in Christology that a Mariology having an integrity of its own first emerged within theology (with Bernard of Clairvaux). Thus, we cannot assign Mariology to Christology alone or to ecclesiology alone (much less dissolve it into ecclesiology as a more or less superfluous exemplification of the Church).

Rather, Mariology underscores the nexus mysteriorum—the intrinsic interwovenness of the mysteries in their irreducible mutual otherness [Gegenüber] and their unity. While the conceptual pairs bride-bridegroom and head-body allow us to perceive the connection between Christ and the Church, Mary represents a further step, inasmuch as she is first related to Christ, not as bride, but as mother. Here we can see the function of the title “Mother of the Church”; it expresses the fact that Mariology goes beyond the framework of ecclesiology and at the same time is correlative to it.15

Nor, if this is the case, can we simply argue, in discussing these correlations, that, because Mary was first the Mother of the Lord, she is only an image of the Church. Such an argument would be an unjustifiable simplification of the relationship between the orders of being and knowledge. In response, one could, in fact, rightly point to passages like Mark 3:33-35 or Luke 11:27f and ask whether, assuming this point of departure, Mary’s physical maternity still had any theological significance at all. We must avoid relegating Mary’s maternity to the sphere of mere biology. But we can do so only if our reading of Scripture can legitimately presuppose a hermeneutics that rules out just this kind of division and allows us instead to recognize the correlation of Christ and his Mother as a theological reality. This hermeneutics was developed in the Fathers’ personal, albeit anonymous, ecclesiology that we mentioned just now. Its basis was Scripture itself and the Church’s intimate experience of faith. Briefly put, it says that the salvation brought about by the triune God, the true center of all history, is “Christ and the Church”��Church here meaning the creature’s fusion with its Lord in spousal love, in which its hope for divinization is fulfilled by way of faith.

If, therefore, Christ and ecclesia are the hermeneutical center of the scriptural narration of the history of God’s saving dealings with man, then and only then is the place fixed where Mary’s motherhood becomes theologically significant as the ultimate personal concretization of Church. At the moment when she pronounces her Yes, Mary is Israel in person; she is the Church in person and as a person. She is the personal concretization of the Church because her Fiat makes her the bodily Mother of the Lord. But this biological fact is a theological reality, because it realizes the deepest spiritual content of the covenant that God intended to make with Israel. Luke suggests this beautifully in harmonizing 1:45 (“blessed is she who believed”) and 11:28 (“blessed . . . are those who hear the word of God and keep it”). We can therefore say that the affirmation of Mary’s motherhood and the affirmation of her representation of the Church are related as factum and mysterium facti, as the fact and the sense that gives the fact its meaning. The two things are inseparable: the fact without its sense would be blind; the sense without the fact would be empty. Mariology cannot be developed from the naked fact, but only from the fact as it is understood in the hermeneutics of faith. In consequence, Mariology can never be purely mariological. Rather, it stands within the totality of the basic Christ-Church structure and is the most concrete expression of its inner coherence.16

4. Mariology—Anthropology—Faith in Creation

Pondering the implications of this discussion, we see that, while Mariology expresses the heart of “salvation history”, it nonetheless transcends an approach focused solely on that history. Mariology is an essential component of a hermeneutics of salvation history. Recognition of this fact brings out the true dimensions of Christology over against a falsely understood solus Christus [Christ alone]. Christology must speak of a Christ who is both “head and body”, that is, who comprises the redeemed creation in its relative subsistence [Selbständigkeit]. But this move simultaneously enlarges our perspective beyond the history of salvation, because it counters a false understanding of God’s sole agency, highlighting the reality of the creature that God calls and enables to respond to him freely. Mariology demonstrates that the doctrine of grace does not revoke creation; rather, it is the definitive Yes to creation. In this way, Mariology guarantees the ontological independence [Eigenständigkeit] of creation, undergirds faith in creation, and crowns the doctrine of creation, rightly understood. Questions and tasks await us here that have scarcely begun to be treated or undertaken.

a. Mary is the believing other whom God calls. As such, she represents the creation, which is called to respond to God, and the freedom of the creature, which does not lose its integrity in love but attains completion therein, Mary thus represents saved and liberated man, but she does so precisely as a woman, that is, in the bodily determinateness that is inseparable from man: “Male and female he created them” (Gen 1:27). The “biological” and the human are inseparable in the figure of Mary, just as are the human and the “theological”. This insight is deeply akin to the dominant movements of our time, yet it also contradicts them at the very core. For while today’s anthropological program hinges more radically than ever before on “emancipation”, it seeks a freedom whose goal is to “be like God” (Gen 3:5). But the idea that we can be like God implies a detachment of man from his biological conditionality, from the “male and female he created them.” This sexual difference is something that man, as a biological being, can never get rid of, something that marks man in the deepest center of his being. Yet it is regarded as a totally irrelevant triviality, as a constraint arising from historically fabricated “roles”, and is therefore consigned to the “purely biological realm”, which has nothing to do with man as such. Accordingly, this “purely biological” dimension is treated as a thing that man can manipulate at will because it lies beyond the scope of what counts as human and spiritual (so much so that man can freely manipulate the coming into being of life itself). This treatment of “biology” as a mere thing is accordingly regarded as a liberation, for it enables man to leave bios behind, use it freely, and to be completely independent of it in every other respect, that is, to be simply a “human being” who is neither male nor female. But in reality man thereby strikes a blow against his deepest being. He holds himself in contempt, because the truth is that he is human only insofar as he is bodily, only insofar as he is man or woman. When man reduces this fundamental determination of his being to a despicable trifle that can be treated as a thing, he himself becomes a trifle and a thing, and his “liberation” turns out to be his degradation to an object of production. Whenever biology is subtracted from humanity, humanity itself is negated. Thus, the question of the legitimacy of maleness as such and of femaleness as such has high stakes: nothing less than the reality of the creature. Since the biological determinateness of humanity is least possible to hide in motherhood, an emancipation that negates bios is a particular aggression against the woman. It is the denial of her right to be a woman. Conversely, the preservation of creation is in this respect bound up in a special way with the question of woman. And the Woman in whom the “biological” is “theological”—that is, motherhood of God—is in a special way the point where the paths diverge.

b. Mary’s virginity, no less than her maternity, confirms that the “biological” is human, that the whole man stands before God, and that the fact of being human only as male and female is included in faith’s eschatological demand and its eschatological hope. It is no accident that virginity—although as a form of life it is also possible, and intended for, the man—is first patterned on the woman, the true keeper of the seal of creation, and has its normative, plenary form—which the man can, so to say, only imitate—in her.17

5. Marian Piety

The connections we have just outlined enable us finally to explain the structure of Marian piety. Its traditional place in the Church’s liturgy is Advent and then, in general, the feasts relating to the Christmas cycle: the Presentation of the Lord and the Annunciation.18

In our considerations so far, we have regarded the Marian dimension as having three characteristics. First, it is personalizing (the Church, not as a structure, but as a person and in person). Second, it is incarnational (the unity of bios, person, and relation to God; the ontological freedom of the creature vis-a-vis the Creator and of the “body” of Christ relative to the head). These two characteristics give the Marian dimension a third: it involves the heart, affectivity, and thus fixes faith solidly in the deepest roots of man’s being. These characteristics suggest Advent as the liturgical place of the Marian dimension, while their meaning in turn receives further illumination from Advent. Marian piety is Advent piety; it is filled with the joy of the expectation of the Lord’s imminent coming; it is ordered to the incarnational reality of the Lord’s nearness as it is given and gives itself. Ulrich Wickert says very nicely that Luke depicts Mary as twice heralding Advent—at the beginning of the Gospel, when she awaits the birth of her Son, and at the beginning of Acts, when she awaits the birth of the Church.19

However, in the course of history an additional element has become more and more pronounced. Marian piety is, to be sure, primarily incarnational and focused on the Lord who has come. It tries to learn with Mary to stay in his presence. But the feast of Mary’s Assumption into heaven, which gained in significance thanks to the dogma of 1950, accentuates the eschatological transcendence of the Incarnation. Mary’s path includes the experience of rejection (Mk 3:31-35; Jn 2:4). When she is given away under the Cross (Jn 19:26), this experience becomes a participation in the rejection that Jesus himself had to endure on the Mount of Olives (Mk 14:34) and on the Cross (Mk 15:34). Only in this rejection can the new come to pass; only in a going away can the true coming take place (Jn 16:7). Marian piety is thus necessarily a Passion-centered piety. In the prophecy of the aged Simeon, who foretold that a sword would pierce Mary’s heart (Lk 2:35), Luke interweaves from the very outset the Incarnation and the Passion, the joyful and the sorrowful mysteries. In the Church’s piety, Mary appears, so to speak, as the living Veronica’s veil, as an icon of Christ that brings him into the present of man’s heart, translates Christ’s image into the heart’s vision, and thus makes it intelligible. Looking toward the Mater assumpta, the Virgin Mother assumed into heaven, Advent broadens into eschatology. In this sense, the medieval expansion of Marian piety beyond Advent into the whole ensemble of the mysteries of salvation is entirely in keeping with the logic of biblical faith.

We can, in conclusion, derive from the foregoing a threefold task for education in Marian piety:

a. It is necessary to maintain the distinctiveness of Marian devotion precisely by keeping its practice constantly and strictly bound to Christology, In this way, both will be brought to their proper form.

b. Marian piety must not withdraw into partial aspects of the Christian mystery, let alone reduce that mystery to partial aspects of itself. It must be open to the whole breadth of the mystery and become itself a means to this breadth.

c. Marian piety will always stand within the tension between theological rationality and believing affectivity. This is part of its essence, and its task is not to allow either to atrophy. Affectivity must not lead it to forget the sober measure of ratio, nor must the sobriety of a reasonable faith allow it to suffocate the heart, which often sees more than naked reason. It was not for nothing that the Fathers understood Matthew 5:8 as the center of their theological epistemology: “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.” The organ for seeing God is the purified heart. It may just be the task of Marian piety to awaken the heart and purify it in faith. If the misery of contemporary man is his increasing disintegration into mere bios and mere rationality, Marian piety could work against this “decomposition” and help man to rediscover unity in the center, from the heart.

________

1 See on this point J. Frings, Das Konzil und die moderne Gedankenwelt (Cologne, 1962), 31-37.

2 Typical of the contrast between the two attitudes, which extends far beyond the domain of Mariology, are the questions posed in J. A. Jungmann’s book, Die Frohhotschaft und die Glaubensverkündigung (Regensburg, 1936); the passionate reaction to this work, which at that time had to be withdrawn from the market, likewise sheds a very clear light on the situation. See the remarks on this episode penned by Jungmann in 1961, in B. Fischer and H. B. Meyer, eds. J.A. Jungmann: Bin Leben fur Liturgie und Kerygma (Innsbruck, 1975), 12-18.

3 See the magisterial presentation of R. Laurentin, La Question mariale (Paris, 1963). Significant, for example, is Pope John XXIII’s warning against certain practices or excessive special forms of piety, even of veneration of the Madonna (19). Such forms of piety “sometimes give a pitiful idea of the piety of our good people”. In the concluding allocution of the Roman Synod, the Pope repeated his warning against the sort of piety that gives the imagination free rein and contributes little to the concentration of the soul. “We wish to invite you to adhere to the more ancient and simpler practices of the Church.”

4 H. Rahner, Maria und die Kirche (Innsbruck, 1951); Rahner, Mater Ecclesia: Lobpreis der Kirche aus dem ersten Jahrtausend (Einsiedeln and Cologne, 1944).

5 A. Müller, Ecclesia-Maria: Die Einheit Marias und der Kirche (Fribourg, 1955).

6 K. Delahaye, Erneuerung der Seelsorgsformen aus der Sicht der frühen Patristik (Freiburg, 1958).

7 R. Laurentin, Court traité de théologie mariale (Paris, 1953); Laurentin, Structure et théologie de Luc 1-2 (Paris, 1957).

8 O. Semmelroth, Urbild der Kirche: Organischer Aufbau des Mariengeheimnisses (Würzburg, 1950); see also M. Schmaus, Katholische Dogmatik, vol. 5, Mariologie (Munich, 1955).

9 I have tried to show that in reality Geiselmann’s formulation of the question misses the core of the problem in: K. Rahner and J. Ratzinger, Offenbarung und Überlieferung (Freiburg, 1965), 25-69; see also my commentary on chapter 2 of Dei Verbum in LthK, supplementary volume 2, 515-28.

10 [In what follows, Ratzinger uses the word Kirche, Church, without the definite article. The reader should bear in mind that he is talking about Church in her personal, Marian reality — TRANS.]

11 See on this point the fundamental presentation of H.U. von Balthasar, “Who Is the Church?,” trans. A.V. Littledale with Alexander Dru, in von Balthasar, Spouse of the Word, Explorations in Theology 2 (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1991), 143-91.

12 See J. Ratzinger, “Kirche als Heilssakrament”, in J. Reikerstorfer, ed„ Zeit des Geistes (Vienna, 1977), 59-70; see also my Das neue Volk Gottes (Düsseldorf, 1969), 75-89.

13 See von Balthasar, “Who Is the Church”; see also the fine interpretation of the Annunciation to Mary in K. Woytyla, Zeichen des Widerspruchs (Zurich and Freiburg, 1979), 50f.

14 G. Söll, Mariologie, Handbuch der Dogmensgeschichte, vol. 4, pt. 3 (Freiburg, 1978).

15 On the title “Mother of the Church”, see W. Dürig, Maria-Mutter der Kirche (St. Ottilien, 1979).

16 See on this point I. de la Potterie’s impressive “La Mère de Jesus et la conception virginale du Pils de Dieu: Étude de théologie johannique”, Marianum 40 (1978): 41-90, esp. 45 and 89f.

17 On the unity of the biological, the human, and the theological, see La Potterie, “Mère de Jésus”, 89f. On the whole discussion, see also L. Bouyer, Woman in the Church, trans. Marilyn Teichert (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1979). This is also the place to mention a lovely observation in A. Luciani’s Ihr ergebener (Munich, 1978), 126. Luciani recounts a meeting with schoolgirls who objected to the alleged discrimination against women in the Church. In response, Luciani brings into relief the fact that Christ had a human mother but did not and could not have a human father: the perfecting of the creature as creature occurs in the woman, not in the man.

18 The new missal—in conformity with the ancient tradition—sees these two feasts as feasts of Christ. Notwithstanding this change, the feasts by no means lose their Marian content.

19 U. Wickert, “Maria und die Kirche”, Theologie und Glaube 68 (1978): 384-407; here, 402.

0 notes

Photo

Psalm 44 - Interpreted

Daily Plenary Indulgence

Per Vatican II, one of the ways to gain a daily plenary indulgence is to read Scripture for ½ hour per day. For Pamphlets to Inspire (PTI), the Scripture readings that inspire us the most are the Psalms. Reading the Psalms and understanding their meaning can sometimes be challenging. In an attempt to draw more individuals to not only read the Psalms, but to understand their meaning, PTI has found an analysis of their meaning by St. Cardinal Robert Bellarmine. The method that will be employed is to list the chapter and verse, and then provide an explanation of that verse. Your interest in this subject will determine how often we will chat about this topic. The Bible that will be used is the official Bible of the Catholic Church and used by the Vatican, that is, the Douay-Rheims or Latin Vulgate version.

The excellence of Christ’s kingdom and the endowments of His Church.

1. My heart hath uttered a good word: I speak my works to the king: my tongue is the pen of a scrivener that writeth swiftly.

1. “My heart hath uttered a good word: I speak my works to the king: my tongue is the pen of a scrivener that writeth swiftly.” This verse forms a preface to the rest of the Psalm. In it the Prophet tells us that the whole proceeded from the mere inspiration of the Holy Ghost, without any corporation on his part. For, though the whole of the holy Scripture is the word of God, and dictated by the Holy Spirit, there is, however, a great difference between the prophecies therein and the historical part, or the epistles. In the prophecies, the holy writers exercised neither their reflection, nor their memory, nor their reasoning powers; but they, simply, either wrote or spoke what God dictated to them, as Baruch testifies of Jeremias, when he said, “with his mouth he pronounced all these words, as if he were reading to me.” But when sacred writers undertook a history, or an epistle, God inspired them with the desire to write, and so directed them, that they should write correctly, and without any errors, but yet in such manner as to oblige them, at the same time, to exercise their own memory and genius, in recording such transactions, and in digesting the order and the manner of so writing, as the author of the Maccabees testifies in chapter 2 of the Second Book, worth reading, but too long to quote here. David, then, when he chanted God’s praises in the Psalms, or deplored his own calamities, or that of his people, drew upon his memory and his talents, and did not compose without some trouble; but when he comes to prophecy, as he does in this Psalm, he claims no part whatever therein beyond the mere service of his pen or of his tongue. Such is the essence of this preface, which was more clearly put by him in 2 Kings 23, where he says, “the Spirit of the Lord hath spoken by one, and his word by my tongue.” He, therefore, says, “my heart hath uttered a good word;” that is, my mind, from the fullness and abundance of the divine light and heavenly revelations, has given to men this Psalm, containing “a good word;” that is, a most grateful and saving word to all mankind. To understand the passage fully, we must go into details. First, observe the word the Prophet uses, “hath uttered,” which, if translated literally, would have been, “belched up,” to show that this Psalm was not composed by him, nor left to his discretion; but, like wind that is involuntarily cast off the stomach, that he was obliged to give it out whether he would or not. Secondly, the Prophet wished to express that he was not giving out all that God had revealed to him, but only a part; for, though belching is a sign of repletion, it is small in itself; for the prophets see many things, “of which it is not lawful for man to speak;” and, therefore, Isaias said, “my secret to myself;” and those who have had revelations from God, confess that they could not find words to express what they saw; and hence, perhaps, the Prophet says, “my heart hath uttered a good word;” not good words, in the plural number. Thirdly, the Psalm is called a “good word,” because it does not predict any misfortune, such as the sacking of the city, or the captivity of the people, as the other prophecies do; but, on the contrary, all that is favorable and pleasant, and likely to bring great joy and gladness. Fourthly, in describing the emanation of this “good word” from the heart of David, he has regard to the production of the word eternal, and seeks to take us by the hand to lead us to understand the generation of the divine word, produced, not as sons are ordinarily produced, by generation, nor by election, nor chosen from a number of sons; but born of his father, the word of his mind, his only word, and, therefore, supremely excellent and good; so that the expression, “good word,” may be peculiarly applied to him. “I speak my works to the King.” Some will have these words to mean: I confess my sins to God; or, I speak those verses of the king; or, I dedicate my works to the king; or, I address the king; which explanations I won’t condemn; but the one I offer will agree better, I think that with what went before and what follows; for, in my opinion, this second sentence of the verse is only an explanation of the first part, and assigns a reason for his having said, “my heart hath uttered a good word;” just as if he said: “I simply attribute all my acts to my King, who was God, and claim nothing for myself; therefore, I have not said, ‘I have written this Psalm;’ but, ‘my heart hath uttered a good word;’ because the thing did not proceed from me, but from the fullness of my illumination;” which he explains more clearly in the next sentence, where he says, “my tongue is the pen of a scrivener that writeth swiftly;” that means, my tongue has certainly produced this Psalm, but not as my tongue, nor as a member of my body that is moved at my pleasure; but as the pen of the Holy Ghost, as if of a “scrivener that writeth swiftly.” He says, (observe) that his tongue is the pen of a scrivener that writeth swiftly, and not the tongue of a spirit that speaketh swiftly; because he means to show that his tongue was like a pen, a mere instrument in announcing the prophecy, and not part of a whole, like the members of the body; “that writeth swiftly,” to give us to understand that the Holy Ghost needs no time to consider what, how, and when matters are to be written; for they only write slowly who required to consider what they are to write, and how they will give expression to their ideas.

2. Thou art beautiful above the sons of men: grace is poured abroad in thy lips; therefore hath God blessed thee forever.

2. “Thou art beautiful above the sons of men: Grace is poured abroad in thy lips; therefore hath God blessed thee forever.” He now commences the praises of Christ, praising him, first, for his beauty; secondly, for his eloquence; as well as for his strength and vigor; thirdly, for the qualities of his mind; lastly, for his royal dignity and power, to which he adds his external beauties, such as the grandeur of his palaces and robes. He begins with beauty, for he is describing a spouse; and, as regards a spouse, eloquence takes precedence of beauty, strength of eloquence, virtue; of strength, and divinity of virtues; and, therefore, he says, “thou art beautiful above the sons of men.” The sentence, though, seems abrupt and obscure, when he does not say who is that beautiful person; but, as we remarked before, his reason for beginning with, “my heart hath uttered a good word,” to let us see that he only uttered some of what he saw, and not the entire; and thus the meaning is: no wonder, Christ, thou shouldest be called beloved, for “thou art beautiful above the sons of men.” Observe, he says, “above the sons of men;” not above the Angels, because God the Son did not become an angel, but man; as if he said: you, my beloved, art man, but “beautiful above the sons of men;” and so he was; for, as regards his divinity, his beauty was boundless; as regards the qualities of his soul, he was more beautiful than any created spirit; and as regards the beauty of his glorified body, “it is more beautiful than the sun;” and “the sun and moon admire his beauty.” Next comes, “Grace is poured abroad in thy lips,” an encomium derived from the graces of his language, thereby adding to that derived from his beauty; and he says, “it is poured abroad in thy lips,” to show that the beauty of Christ’s language was natural and permanent, and not acquired by study or practice; for we read in the Gospel, Luke 4, “and they wondered at the words of grace that proceeded from his mouth;” and, in John 7, “never did man speak like this man.” Saints Peter, Andrew, James, John, Philip, and especially Saint Matthew, felt the force of his words, the secret power in them that cause them, by a simple call, to abandon their all, and follow him. What is more wonderful! The sea, the winds, fevers and diseases, nay, even the very dead, felt the power of his voice; which, after all, must appear no great wonder, when we consider that it was the divine and substantial word that spoke in his sweetest and most effective accents, in the flesh he had assumed; “therefore hath God blessed thee forever.” No wonder you should “be beautiful,” and that “grace should be on thy lips,” because “God hath blessed thee forever.”

3. Gird thy sword upon thy thigh, O thou most mighty.

3. “Gird thy sword upon thy thigh, O thou most mighty.” From the praise of his beauty and his eloquence, he now comes to extol his bravery; and, by a figure of speech, instead of telling us in what his bravery consists, he calls upon him to “gird thy sword upon thy thigh, O thou most mighty;” as much as to say: come, beloved of God, who art not only most beautiful and graceful, but also most valiant and brave; come, put on thy armor; come, and deliver your people; and he tells us in the following verse was sort of armor he means, saying:

4. With thy comeliness and thy beauty set out, proceed prosperously, and reign. Because of truth and meekness and justice: and thy right hand shall conduct thee wonderfully.

4. “With thy comeliness and thy beauty set out, proceed prosperously, and reign. Because of truth and meekness and justice: and thy right hand shall conduct thee wonderfully.” The words, “with thy comeliness and thy beauty,” may be connected with the preceding verse, and the reading would be, “gird thy sword upon thy thigh, and thy comeliness and thy beauty;” or they can be connected with what follows; thus, “with thy comeliness and thy beauty set out, proceed prosperously, and reign;” but, in either reading, the meaning is the same; namely, that Christ has no other arms but “his beauty and his comeliness.” To understand which we must remember, that true and perfect beauty, as St. Augustine says, is the beauty of the soul that never stales, and pleases the eye not only of men, but even of Angels, aye, even of God, who cannot be deceived. For, as ordinary beauty depends on a certain proportion of limb, and softness of complexion; thus the beauty of the soul is made up of justice, which is tantamount to the proportion of limb, and wisdom, which represents beauty of complexion; for his shines like light, or rather, as we read in Wisd. 7, “being compared with the light she is found before it.” The soul, then, that is guided in its will by justice, and in its understanding by wisdom, is truly beautiful. For these two qualifications make it so, and through them most dear to God; and are, at the same time, the most powerful weapons that Christ used in conquering the devil. For Christ contended with the devil, not through his omnipotence, as he might have done, but through his wisdom and his justice; subduing his craft by the one, and his malice by the other. The devil, by his craft, prompted the first man to anger God by his disobedience; and thereby to deprive God of the honor due to him, and all mankind of eternal life; uniting malice with his craftiness, and prompted thereto, moreover, by envy, seeing the place from which he had fallen was destined for man; but the wisdom of Christ was more than a match for such craft, because, by the obedience he, as man, tendered to God, he gave much greater honor to him than he had lost by the disobedience of Adam; and by the same obedience secured a much greater share of glory for the human race than they would have enjoyed, had Adam not fallen. With that, Christ, by his love, (which is the essence of true and perfect justice,) conquered the envy and malice of the devil, for he loved even his enemies, prayed on the very cross for his persecutors, chose to suffer and to die, in order to reconcile his enemies to God, and to make them from being enemies, his friends, brethren, and coheirs; and all that is conveyed in the expression, “in thy comeliness and thy beauty;” that is to say, in the comeliness of thy wisdom, and the beauty of thy justice, guided and armed with the sword, and the bow set out, proceed prosperously and reign; which means, advance in battle against the devil, prosper in the fight, and after having conquered and subdued the prince of this world, take possession of your kingdom, that you may forever after rule in the heart of man, and through faith and love. “Because of truth and meekness and justice, and thy right hand shall conduct thee wonderfully.” He tells us why Christ should reign, and that is because he has the qualities that belong to a king; truth, meekness, and justice, from which we learn, that a king should be truthful and faithful to what he says, and just in what he does; which attributes are applied to God himself, in Psalm 144, “the Lord is faithful in all his words, and holy in all his works;” but, as there is a certain roughness of severity consequent on all justice, and is like a blemish on it, with Christ’s justice, which is more perfect, he couples meekness. For Christ is meekly just, judging, to be sure, with the strictest justice, but without harshness, or moroseness, conciliating instead of repelling those whom he judges. “And thy right hand shall conduct thee wonderfully.” By governing in such temper you will see your kingdom increase to a wonderful extent, and you will need no external aids, for your own “right-hand,” your own strength and bravery will suffice “to thee wonderfully,” and so extend your kingdom until you shall have “put all your enemies under your footstool.”

5. Thy arrows are sharp: under thee shall people fall, into the hearts of the king’s enemies.

5. “Thy arrows are sharp: under thee shall people fall, into the hearts of the king’s enemies.” He tells us how the right hand of Christ will conduct him so wonderfully in extending his kingdom, because “the arrows” that you will let fly at them “are sharp,” and will, therefore, penetrate “into the hearts of the king’s enemies;” your enemies will fall before you, and will be subdued by you. The arrows here signify the word of God, or the preaching of his word, for such are the instruments Christ generally uses in extending his kingdom; hence, he says in Psalm 2, “but I am appointed king by him over Sion his holy mountain, preaching his commandment.” The word of God is called a sword, an arrow, a mallet, and various other instruments, for it has some similarity to them all. It is called a sharp arrow, for it wonderfully sinks into the heart of man, much deeper than the words of the most eloquent orator, as the apostle, Heb. 4, says, “for the word of God is living and effectual; and more penetrating than any two edged sword.” The words, “under thee shall people fall,” should be read as if in a parenthesis; and they will only fall, and not be killed; they will only die to sin that they may live to justice; that they may be subject to Christ, to be subject to whom is to reign.

6. Thy throne, O God, is forever and ever: the scepter of thy kingdom is a scepter of uprightness.

6. “Thy throne, O God, is forever and ever: the scepter of thy kingdom is a scepter of uprightness.” He now comes to the supreme dignity of the Messiah, openly calls in God, and declares his throne will be everlasting. This passage is quoted by St. Paul to the Hebrews, to prove that Christ is as much above the angels, as is a master over his servant; or the Creator above the creature. He then, says, “thy throne, O (Christ) God,” will not be a transient one, as was that of David, or Solomon, but will flourish “forever and ever.”

7. Thou hast loved justice, and hated iniquity: therefore God, thy God, hath anointed thee with the oil of gladness above thy fellows.

7. “Thou hast loved justice, and hated iniquity: therefore God, thy God had anointed thee with the oil of gladness above thy fellows.” This verse may be interpreted in two ways, according to the force we put upon the word “therefore” in it. It may signify the effect produced, and the meaning would be: as you have loved justice and hated iniquity, by being “obedient unto death, even to the death of the cross,” therefore God anointed thee with the oil of gladness, that glorified thee, “and gave thee a name that is above every name, that at thy name every knee should bend, of those that are in heaven, on earth, and in hell.” Such glorification is properly styled “the unction of gladness;” because it puts an end to all pain and sorrow; “above thy fellows,” has its own signification; for, though the angels have been, and men will be, glorified, nobody ever was, or will be, exalted to the right hand of the Father; and nobody ever got, or will get, a name above every name, with the exception of Christ, who is the head of men and angels, and is at the same time God and man. In the second exposition, the word “therefore” is taken to signify the cause, and the meaning would be: you loved justice and hated iniquity, because God anointed you with the oil of spiritual grace in a much more copious manner then he gave it to anyone else; and hence it arose that your graces were boundless, while all others got it in a limited manner, and only through you. Such is the explanation of St. Augustine, who calls our attention to the repetition of the word of God in this verse, and says, the first is the vocative, the second the nominative case, make in the meaning to be: “O Christ God! God your Father has anointed thee with the oil of gladness. The anointing, of course, applies only to his human nature.

8. Myrrh and stacte and cassia perfume thy garments, from the ivory houses: out of which:

8. “Myrrh and stacte and cassia perfume thy garments, from the ivory houses: out of which: No explanation given.

9. The daughters of king’s have delighted thee in thy glory. The queen stood on thy right hand, in gilded clothing: surrounded with variety.

9. “The daughters of kings have delighted thee in thy glory. The queen stood on thy right hand, in gilded clothing: surrounded with variety.” A very difficult and obscure passage. The words need first to be explained. Myrrh is a well known bitter aromatic perfume. Stacte is a genuine term for a drop of anything, but seems to represent aloes here, which is also a bitter, but odoriferous gum, but different from myrrh; for we read in the Gospel, of Nicodemus having bought a hundred pounds of myrrh and aloes for the embalmment of Christ. Cassia is the bark of a tree, highly aromatic also. By houses of ivory are meant sumptuous palaces, whose walls are inlaid or covered with ivory; just as Nero’s house was called golden, and the gates of Constantinople the Golden Gates, not because they were solid gold, but from the profusion of gilding on them; and thus is interpreted the expression in 3 Kings 22, “the ivory house built by Achab;” and, in Amos 3, “the ivory houses will be ruined.” The expression “daughters of kings,” means the multitudes of various kingdoms; for the holy Scriptures most commonly use the expression, daughter of Jerusalem, daughter of Babylon, daughter of the Assyrians, of Tyre, to designate the people of those places; or the words may be taken literally to mean daughters of princes; that is, holy, exalted souls, for the whole sentence is figurative. To come now to the meaning. These aromatic substances represent the gift of the Holy Ghost, who diffuses a wonderful odor of sanctity; and the Prophet having in the previous verse spoken of the unction of Christ, when he said, “therefore God, thy God, hath anointed thee,” he now very properly introduces the myrrh, aloes, and cassia, in explanation of the beautiful odors consequent on such anointing, of which St. Paul speaks, 2 Corinthians 2, when he says, “for we are unto God the good odor of Christ.” And as Christ, in his passion, especially exhaled the strongest odors of virtue, of resolute patience, of humble obedience, and ardent love, he, therefore, brings in myrrh, bitter, but odoriferous, to represent patience; aloes, also bitter, though aromatic, to represent humility and obedience: of which St. Paul says, “he humbled himself, becoming obedient even unto death;” and, finally, cassia, warm and odoriferous, to represent that most ardent love that caused him to pray even for his persecutors, while they were nailing him to the cross. All these aromas flowed “from the garments and the ivory houses” of Christ. The “garments” mean Christ’s humanity, that covered his divinity, as it were, with a garment or a veil; and the “ivory houses” represent the same humanity, which, like the fair temple of ivory, afforded a residence to the divinity. It is not unusual in the Scriptures to call human nature by the name of garment and house; thus, in 2 Cor. 5, he unites them when he says, “for we know if our earthly house of this habitation be dissolved, that we have a building of God, a house not made with hands, eternal in heaven. For in this also we groan, desiring to be clothed over with our habitation, which is from heaven, yet so that we may be found clothed, not naked. For we also who are in this tabernacle do groan, being burdened: because we should not be unclothed, but clothed over; that what is mortal may be swallowed up by life.” Here we have this mortal body of ours called a house and a tabernacle as also a garment, with which “we would not be unclothed, but clothed;” and the heavenly house, in turn, a garment and a habitation. So with the human nature of Christ, that diffused such sweet odors of the virtues, it may be called a garment, and a house of ivory at the same time; unless one may wish to refer the garment to his soul, and the house of ivory to his body, which Christ himself seems to have had in view when he said to the Jews, “destroy this temple, and in three days I will build it up again.” The word “Ivory houses,” being in the plural number, is an objection of no great value, for the Prophet calls it a noun of multitude; just as we call a large establishment the buildings, though there, in reality, is only one object before our mind. “Out of which the daughters of kings have delighted thee in thy glory;” that is, from which perfumes, exhaling from the vestments and ivory houses of thy humanity; “the daughters of kings;” whether it means the royal and exalted souls, or multitudes of people from various kingdoms; “have delighted thee,” as they “ran after thee to the odor of thy ointments.” For Christ is greatly delighted when he sees multitudes of the saints, attracted by his odors, running after them; and, in fact, anyone, once they get but the slightest sense of such odors as flow from the patience, humility, and love of Christ, cannot be prevented from running after them, and will endure any amount of torments sooner than suffer themselves to be separated from him, explaining, with the apostle, “who shall separate us from the love of Christ?” And in this respect do the daughters of kings, when they run after the odor of his ointments, especially delight our Lord, because they do it to honor him, with the pure intention of glorifying him. The martyrs glorified God wonderfully when, by their sufferings, they ran after their master, to which himself alluded when he predicted Peter’s suffering, on which the Gospel remarks, “signifying by what death he should glorify God.” “The queen stood on thy right hand in gilded clothing, surround with variety.” The prophecies hitherto regarded the bridegroom; he now turns to the bride, by which bride, as all commentators allow: is meant the Church; for St. Paul to the Ephesians 5, lays down directly that the church is the bride of Christ. The principal meaning of the passage, then, is to take the bride as designating the Church. Any faithful, holy soul even, may be intended by it; particularly the Blessed Virgin, who, together with being his mother according to the flesh, is his spouse according to the spirit, and holds the first place among the members of the Church. It is, then, most appropriately used in the festivals of the Blessed Virgin, and of other virgins, to whom, with great propriety, the Church says, “come, spouse of Christ.” David, then, addressing Christ, says, “the queen stood on thy right hand.” Thy spouse, who, from the fact of her being so, is a queen, stood by thee, “on thy right hand,” quite close to thee, in the place of honor, on thy right hand, “in gilded clothing,” in precious garments, such as become a queen. Take up now the several words. The word “stood,” in the perfect, instead of the future tense, is used here, a practice much in use with the prophets, who see the future as if it had actually passed; and, as St. Chrysostom remarks, she stood, instead of being seated, as queens usually are, to imply her inferiority to God, for it is only an equal, such as the Son, that can sit with him; and, therefore, the Church, as well as all the heavenly powers, are always said to stand before God. The word, in Hebrew, implies standing firmly; as if to convey that the bride was so sure, safe, and firm in her position that there could be no possible danger of her being rejected or repudiated.

10. Harken, O daughter, and see, and incline thy ear and forget thy people and thy father’s house.

10. “Hearken, O daughter, and see, and incline thy ear: and forget thy people and thy father’s house.” He now addresses the Church herself; in terms of the most pious and friendly admonition. He calls her “daughter,” either because he speaks in the person of God the Father, or as one of the fathers of the Church. It applied to the Blessed Virgin, it requires no straining of expression, she being truly the daughter of David. “Hearken, O daughter,” hear the voice of your spouse, “and see,” attentively consider what you hear, “and incline thy ear;” humbly obey his commands, “and forget thy people and thy father’s house,” that you may the more freely serve your spouse, and forget the world and the things that belong to it, for the church has been chosen from the world, and has come out from it; and though it is still in the world, it ought no more belong to it then does its spouse. By the world, is very properly understood the people who love the things of the world, which same world is the mansion of our old father Adam, who was driven into it from Paradise. The word “forget” has much point in it, for it implies that we must cease to love the world so entirely and so completely, as if we had totally forgotten that we were ever in it, or that it had any existence.

11. And the king shall greatly desire thy beauty: for he is the Lord thy God, and him they shall adore.

11. “And the king shall greatly desire thy beauty: for he is the Lord thy God, and him they shall adore.” He assigns a reason why the bride should leave her people and her father’s house, and be entirely devoted to the love of her heavenly spouse, and to his service, for thus “the king shall greatly desire thy beauty,” and wish to have thee above him. And since the principal beauty of the bride is interior, as will be explained in a few verses after this one, consisting in virtue, especially in obedience to the commandments, or in love of which all the commandments turn; he therefore adds, “for he is the Lord thy God;” that is to say, the principal reason for his so loving your beauty, which is based, mainly on your obedience, is, because “he is the Lord thy God.” Nothing is more imperatively required by the Lord from his servants, or by God from his creatures, than obedience. And for fear there should be any mistake about his being the absolute Lord and true God, he adds, “and him they shall adore;” that is to say, your betrothed is one with whom you cannot claim equality, he is only so by grace, remaining still your Lord, and the Lord of all creatures, who are bound to adore him.

12. And the daughters of Tyre with gifts, yea, all the rich among the people, shall entreat thy countenance.

12. “And the daughters of Tyre with gifts, yea all the rich among the people, shall entreat thy countenance.” Having stated that the bridegroom would be adored, he now adds, that the bride too would get her share, would be honored as a queen, by presents and supplications. “And the daughters of Tyre with gifts, yea, all the rich among the people, shall entreat thy countenance;” the daughters of the Gentiles, heretofore enemies to your Lord, will be brought under subjection to him, and will come to you, “and entreat your countenance,” will by your intercession, moving you not only by words and entreaties, but by gifts and presents: “all the rich among the people,” because, if the rich take up anything, consent or agree to it, the whole body generally follow them. “The daughters of Tyre,” the women of the city, meaning the whole city, but the women are specially named as generally having more immediate access to the queen, and more so than men have to the king; and as the bride here does not represent a single individual, but the Church, which is composed of men and women, so by the daughters of Tyre we understand, all the Gentiles, be they men or women. Tyre was a great city of the Gentiles, bounding the land of promise, and renowned for its greatness and riches, and is therefore made here to represent all the Gentiles. “With gifts,” the offerings which the converted Gentiles offered to build or to ornament churches, or to feed the poor, or for other pious purposes. “Shall entreat thy countenance;” some will have it, that thy countenance means the countenance of Christ, but the more simple explanation is, to refer to the Church. The expression is a Hebrew one, which signifies, to intercede for, or to deprecate one’s anger: thus Saul says, in 1 Kings 13, “and I have not appeased the face of the Lord;” and in Psalm 94, “let us preoccupy his face and thanksgiving;” and in Psalm 118, “I entreated thy face with all my heart.” Entreating the face is an expression taken from the fact of looking intently on the face of the person we seek to move, and judging from its expression, whether we are likely to succeed or to be refused.

13. All the glory of the king’s daughter is within in golden borders,

13. “All the glory of the king’s daughter is within in golden borders.” No explanation given.

14. Clothed round about with varieties. After her shall virgins be brought to the king: her neighbors shall be brought to thee.

14. “Clothed round about with varieties. After her shall virgins be brought to the king: her neighbors shall be brought to thee.” Having spoken at such length of the beauty of the bride, for fear anyone may suppose those beauties were beauties of the person, he now states that all those beauties were interior, regarding the mind alone. “All her glory,” whether as regards her person or her costly dress, are all spiritual, internal, and to be looked for in the heart alone. Hence St. Peter admonishes the women of his time to take the bride here described, as a model in the decoration of their interior. “Whose adorning let it not be the outward plaiting of the hair, or the wearing of gold, or the putting on of apparel, but the hidden man of the heart, in the incorruptibility of a quiet and meek spirit, which is rich in the sight of God.” We are not, however, hence justified in censuring the external decorations of the Church, and the altars, on the occasion of administering the sacraments, and on great festivals, for question is here, not of material edifices, but of men, who are the people of God, and members of Christ, whose principal ornament and decorations should consist in their virtues; from which virtues, however, good works ought to spring, “that those who see them, may glorify our Father who is in heaven,” as our Savior says. The “golden borders” most appositely represent charity, which is compared to gold, as being the most precious and valuable of all the virtues. We have already explained the variegated vestment, for which vestment the apostle seems to speak, when he says, “put ye on the bowels of mercy, benignity, humility, modesty, patience. After her shall virgins be brought to the king.” Though there is only one spouse of Christ, one only beloved by him, the universal Church, there are a certain portion specially beloved by him, enjoy certain perogatives; and they are those who have dedicated their virginity to God, in the hope of being better able to please them; of whom the apostle says, “he that is without a wife, is solicitous for the things that belong to the Lord, how he may please God. But he that is with a wife, is solicitous for the things of the world, how he may please his wife: and he is divided. And the unmarried woman and the virgin thinketh on the things of the Lord, that she may be holy both in body and spirit. But she that is married thinketh on the things of the world, how she may please her husband.” Of such the Prophet now speaks, and in these verses extols that virginity so precious in the sight of Christ, the virgin “who feedeth among the lilies.” After her shall virgins be brought to the king. “Next to his principal bride, the Church, shall rank all those celestial brides who have consecrated their virginity to God.” Her neighbors shall be brought to thee; that is, the only virgins that shall be introduced will be those that were neighbors to thee, by reason of acknowledging thy true Church.

15. They shall be brought with gladness and rejoicing: they shall be brought into the temple of the king.