#not with pythagoras it's the same basic shit no matter what

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I’m mad at Phythagoras for having such a big name like when you hear “Pythagoras’ theorem” it’s scary before you learn it because damn big greek name followed by ‘theorem’ but the thing itself is like..the simplest shit

#when i learned it i was like damn thats it#and you know how like some concepts are easy but there's like one question that's impossible#not with pythagoras it's the same basic shit no matter what#fatima.txt

1 note

·

View note

Text

thinkin about an alternate take on odyssey’s cult of kosmos storyline that may culminate in a blatant ripoff of valhalla but bear with me here lmao

instead of deimos continually antagonizing you the entire game as you try desperately to convince them that the cult is simply using them, deimos is actively trying to recruit you to fight alongside them. you are both demigods descended from sparta’s greatest hero, two sides of the same coin, etc. etc. as you go around killing cultists you get those cutscenes where each cultist gets to have one final say (just like all the other ac games) and while many joined and profited from the war for selfish reasons, there are enough of those who had lofty ideals that maybe you start to see that the two warring nations are both truly broken beyond repair. people are suffering because of the war, and for every callous profiteer that joined the cult to make a quick buck there’s also someone who joined just to survive, or because if you can’t beat em, join em -- at the least, they could then maybe stand a chance at protecting the people they love, even if it means others will have to pay that price. that’s just the way the world works, right?

and so after the battle of amphipolis and after killing the rest of the cult, you return to the cave of gaia in delphi and find not only deimos but also the ghost of kosmos down there, in front of the pyramid. deimos is still nursing his wounds from where kleon shot him, and the ghost finally unveils herself. both get their villain-y monologues about how it’s all for the greater good, everyone who died along the way was sacrificing themselves for a better world and the world will remember what they did -- but that will only happen if you join them. if you’re there to make sure they mattered. and the pyramid with its weird little artifacts still draws you in like it did that first night you infiltrated their meeting, and you and deimos and the ghost all touch it and you all get teleported via videogame magic or isu technology or whatever the fuck who cares it’s just a stupid scifi game let me live to...

atlantis?

it’s the exact same look and feel as the dlc: humans and gods living in (apparent) harmony, people are happy, families are together, there’s laughter and music and plenty of food and leisure. the buildings are gorgeous, there’s like fountains and gardens and aquariums and other cool shit, and if not for the weird isu tech all over the place you’d almost think it was elysium. but it’s not elysium, because you’re not dead. deimos isn’t dead. and you’ve never felt more at peace. the ghost tells you that this is all perfectly achievable, if only you join them in helping construct this world from the ashes of the old. deimos tells you that they’ve seen this in their dreams; the world was truly like this once, and it could be again.

there’s no war to be fought here; no pain or suffering or loss. deimos sheathes their sword and tells you that they cannot just go back to being family in the real world, not after everything that has happened and all the suffering you both have experienced -- out in the real world, you were both doomed to be nothing more than shattered bones and streaks of gore at the foot of sparta’s sacred mountain. you don’t matter out there, and you never did, and they know you are tired of trying to prove that you do, because they’re tired too. but in here, in this world, you could be together. you could be the siblings you never got the chance to be. this is what they were fighting for all along. they gave their name, and their life, and their innocence and their pain -- all to achieve this. and with your help they can finally stop calling themself deimos and reclaim their old name. or the two of you could find new names. you could be gods. you could slaughter the old gods, the ones whose prophecies doomed you both to die at the foot of mount taygetos (deimos still doesn’t know the cult orchestrated that lmao listen the brainwashing runs deep). you could be anyone you want here.

all of this feels so real. you feel like you could stay here forever.

deimos extends their hand. you reach out to take it. to join them.

and something tumbles out of your pouch.

it’s a little wooden eagle, a child’s toy, battered and all scratched up with most of its defining features worn away. you know it well. you know every contour of it because a little girl gave it to you when you left the island where you and she once lived, to go make a name for yourself in a war that never seemed to end, until suddenly it did. you know this toy eagle because you folded that little girl’s cold, dead, still-bloody fingers around it one terrible night in athens. you were told, later, that the eagle burned with her on the pyre your friends constructed for her. and so the only reason this eagle is here now, the only reason you can run your hands along its outstretched wings and trace the whorls of the woodgrain with your fingertips and feel the slight weight of it in your palm is because none of this is real.

what is real is this: the cult existed, and phoibe died. leonidas died. perikles died. brasidas died. and you cannot live in a world where the very act of dying for the world they didn’t know they were helping to shape is the one thing that becomes the defining feature of their legacies. where their lives become nothing more than some kind of grotesque buttressing to prop up the very people who got them all killed.

there’s some kind of bossfight against deimos, who, despite their appeals to you to join them as a battlefield companion and true siblings after too many years lost between you, still doesn’t hesitate to turn against you as they always have the moment things do not go their way. because that’s the way it is between the two of you: they push, and you push back.

and the more you fight, the more atlantis crumbles. the others don’t seem to notice; they simply sit there and laugh and sip wine and dance and sing as stone after stone falls from the vast turrets and crushes first their companions, then them, into blood and bone and gristle. there’s a gate up on the highest tower of the city, and you know instinctively that without it you’ll be stuck here in this strange dream-limbo, fighting your sibling for eternity as both worlds, dream and real, carry on with or without you. and as you make your way to it (maybe there’s some sweet parkour opportunities here with like falling debris and such) deimos gives chase and as you draw closer to the gate you start to see that it’s not empty at all, but full of people crowing in to take a peek at all the commotion.

there’s sokrates and hippokrates and aristophanes. alkibiades looking uncharacteristically worried, and [insert any npc lieutentants you’ve recruited like roxana or odessa]. xenia is there, and so is anthousa. kyra and/or thaletas, too (depending on the outcome of the mykonos questline). and a gang of plucky little kids, all cheering you on: khloe, the girl with the clay friends; arsenios, the tour-guide-turned-con-artist; ardos and his caretaker. (and i guess nikolaos and stentor if they’re still alive lmao) (maybe pythagoras is allowed too but he’s on thin fucking ice)

and, of course, myrrine. standing at the forefront, shoulder to shoulder with barnabas and herodotos. all three of them -- alongside everyone else you’ve ever allied with, fought beside, or helped out -- everyone who loves you, everyone you’ve ever loved -- they’re beckoning you home. back to the real world, where they matter. where you matter.

where you have always mattered.

you’re so close to taking your mother’s hand, you can feel the warmth of her fingertips -- and then you hear a scream below you.

it’s deimos, and they’re falling. maybe they tripped in their haste to catch you. maybe some of the falling rubble knocked them off-balance. it doesn’t matter. the only thing that matters is that your sibling is falling to their doom. again. and there’s nothing you can do about it.

except this time there definitely is.

so you leap from the ledge with all the strength you have, the roaring in your ears drowning out myrrine’s shouts. you’ve fallen from greater heights, after all, and lived to tell the tale. this is nothing. and this time you’ll catch your sibling, because this is your dream, too. and in your dream, you can do whatever the fuck you want.

you catch deimos, the both of you still falling, the ground rushing up to meet you -- and you both wake in the cave of gaia with a jolt. each of you still have a hand on the pyramid, and you make eye contact. they give you the slightest of nods, as if to say i’m okay. i’m awake.

the ghost is still asleep, head bowed, eyes flitting to and fro behind closed eyelids, both hands still on the pyramid.

you destroy the pyramid with your grandfather’s spear. this wakes the ghost. she’s furious, and tells you that you’ve made a terrible mistake. the cult of kosmos may be extinguished, but the ideals she worked toward are not. (basically this kind of mirrors the whole spiel about the philosopher-king or whatever tf the ghost said at the end of the actual in-game storyline that foreshadowed the order of ancients and eventually the templars)

deimos looks to you and mutters that it’s your choice what to do next. the ghost tries to appeal to them but they’ve run out of fucks to give. they leave.

[kill the ghost] what it says on the label. you get a nice little ac-esque assassination cutscene and it’s actually got some emotional weight to the decision/scene, unlike the game.

[walk away] leave the ghost in the cave. the pyramid is gone, the cult is dead, your sibling is free. the ghost will live the rest of her life looking over her shoulder, knowing that the grandchildren of leonidas have seen her for what she is. knowing that whatever she does next, they’ll be watching closely.

when you leave the cave, you see deimos, pacing as they overlook the view of phokis from mount parnassos. it’s high noon and the sun glints brilliantly off their gilded armor. they glance at the temple of apollo and remark how strange it is to be standing here together, so close to the place where both your fates were sealed with just a few words from a puppet pythia a lifetime ago.

you ask what they’re going to do, now that the cult is gone.

the peace of nicias isn’t going to hold, they tell you. the war will start again soon enough, and when that happens both athens and sparta will be looking for champions to fight for their side.

dialogue choices:

[i’ll see you on the battlefield] you and your sibling part ways. subsequent conquest battles have a chance of spawning a bossfight against deimos who is fighting for the other side -- neither of you can perma-kill the other so you can encounter/fight them over and over again. at the end of the conquest battle, no matter who wins, you can see them walking up and down the battlefield and you can have some silly little sibling banter, which changes depending on who wins/loses the battle

[join me, fight with me] deimos joins your crew just like in the game. unlike the game, you can interact with them at any time while they’re walking up and down your ship and have sibling banter because i just want some decent fucking sibling banter in this game

no matter which option you pick, the first time you return to sparta after finishing this storyline you’ll have the option of entering your old family home and triggering the family dinner cutscene with all the surviving members of your family because goddammit even after all this wishful revisionism i still love that silly little family dinner

anyway in conclusion this is what i want out of odyssey, thanks for coming to my TED talk, don’t forget to smash that like&subscribe the way the eagle bearer definitely smashed brasidas’ fine spartan ass offscreen bc ubisoft were too smoothbrained to give us the romance we deserved

#tuserautumn#userbryn#assassin's creed#ac odyssey#cool story charlotte#can u tell i listened to 'leaving valhalla' one too many times on loop tonight and have been cryin in the club @ that doorway scene#idk fam i just want a remaster/retweaking of odyssey#where all the art direction and the characters and music and general story beats are the same#but with a more coherent narrative that doesn't disintegrate the moment you start prodding at the plot holes#yes i'm fully aware that deimos dies in novel/wiki canon NO i do NOT care. FUCK that. in this version deimos lives#anyway ub*s*ft hmu there's way more odyssey-reboot ideas where this came from and they're all WAY hornier + involve pegging spartan general#better yet just let me buy the fucking franchise already cmon#i've got IDEAS#i mean they're not GOOD ideas but like.#must ideas be good??? is it not enough simply fulfill all the desires in my selfish little gremlin heart????????

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

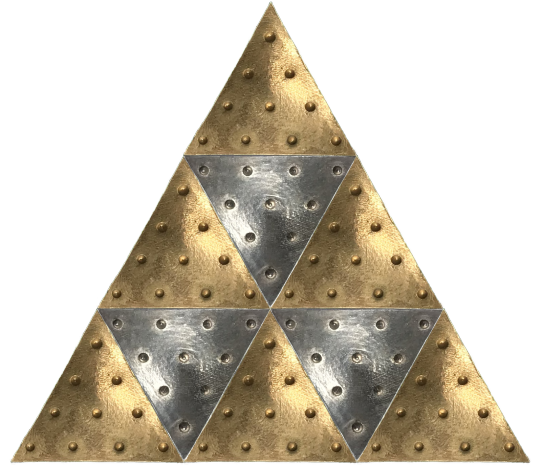

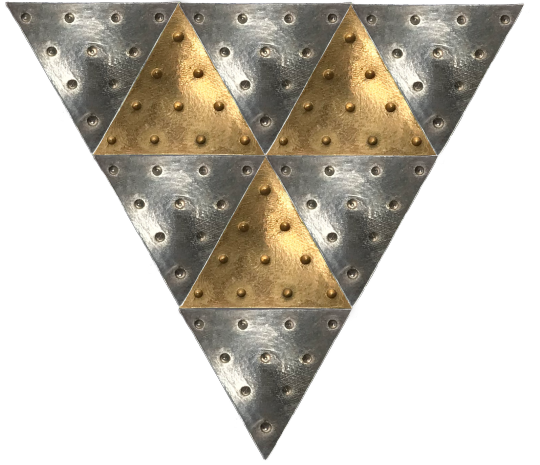

Notes on the Tetractys: Vol. 1

I have promised to do some writing about the Tetractys, so here it goes.

The first time this symbol blipped onto my radar was in 2009, when I learned about the it via somebody else’s artwork. At that point I had studied a bit of Greek philosophy and a heap of that Hebrew-adjacent mysticism that modern occultists appear to have bet everything on.

There’s literally no end to the amount of information out there about all of my favorite subjects, just waiting to be learned! This is why it’s so daunting for beginners who want to connect to certain magickal traditions: you want to know your shit, but we’re talking about areas of study which are notoriously difficult to access, and in many cases have been selected against in the great evolutionary arms-race of education. And then there are the gatekeepers upon gatekeepers upon gatekeepers...

The internet is an amazing tool for educating oneself, but there are so many ways to use it, and not a lot of instructions (just endless corrections). It takes a dexterous and inquisitive mind to exercise its potential in any focused way — to know what there even is to search for in the first place, and then how to search for it, how to dig into the crevices you find between related subjects and mine them for additional information... which informs future searches, etc.

But we still have it so much easier than anyone who came before us! Reading about the ways in which knowledge was passed down from teacher to student, from generation to generation, during the times of Pythagoras and other Greek philosophers is just fascinating to me. How did they manage to keep the chain from breaking?

Then you realize how many chains did break along the way. Those we have access to are just the ones which gained a critical mass of interest, or happened to be preserved, or managed to survive all the historical incidents that have wiped out massive amounts of history.

We gradually realize that at virtually any point during its existence, a thing can be lost. Sometimes these things are lost on purpose, other times they slip through our fingers as we reach for other things. And then in some rare instances, a lost thing can be found again. So there’s often a continuity in a thing’s existence that isn’t evident in our historical record — which, from a distance, could probably be visualized as a string of lights blinking on and off again as various things (ideas, objects, people) are lost, forgotten, rediscovered, and then lost again, blipping across humankind’s awareness and then retreating, over and over across centuries.

Basically we humans are playing a giant “don’t let the balloon touch the floor” game with our own history, except with billions of people and balloons in play at once, and some of the players unfairly seem to be armed with pointy sticks. It’s an absurdly clumsy scenario, and no matter how well we try to play together... suffice to say, there will be casualties.

The Greeks knew this. They’d already seen it! Which is why some of the traditions you read about were so strict, or so eccentrically intense. These teachers knew their entire body of work could go up in smoke, literally anytime. In many cases they’d observed it firsthand. In some instances, they’d personally wielded the torches! Since the very dawn of technology, probably pre-dating language itself, humans have been engaged in informational warfare.

This is one way that teachers, inventors and explorers actually manage to change the course of history: by determining who can be trusted with emerging information. That’s why security and access remain central to conversations about technology to this very day. What is beneficial to keep secret, and what should be made available to the public?

Some make these choices wisely, others choose unwisely, and everything we see around us is basically the grand result of all those choices.

Wait, wasn’t this supposed to be about the Tetractys?

*bops balloon back toward ceiling*

There’s a reason why certain symbols and designs from antiquity remain in play today, thousands of years later. It’s the same reason that creators are constantly trying to create new ones, or in some cases just scooping up old symbols, dusting them off, remixing and repurposing them for a new mission.

Symbols and patterns are sticky. We like looking at them, thinking about them, playing with them. Remember how you did this as a child, over and over: encountering a new symbol, you would draw it, repeat it. As a product of embedding it in your own memory, you leave it where it may be found by someone else. As a technology, symbols are uniquely equipped for longevity in the human world.

The human eye and brain are linked in a way that’s predisposed to recognize patterns, and pattern recognition is key to learning (among many other things) mathematics.

Mathematics (which I’m terrible at, so don’t worry, this isn’t about to become a math blog) will always the key to understanding the reality we inherited, and to seeing its potential as we gradually fabricate a new one.

The Tetractys is both a symbol and a pattern, which makes it especially sticky and especially fun to play with. With very little explanation, its layers of meaning begin to unfold in the mind. It teases, it reveals, it obscures. The Tetractys nudges us new toward thresholds of awareness, echoing the cascading effect of reality’s formation described in the Tetractys itself.

As such, it remains its own best recommendation. Is it any wonder that Pythagoreans flipped their collective lids over it?

The author at Organelle writes:

“What [Pythagoras] was gave us is nothing like what it at first appears to be. This is why people were swearing by his name for having brought this simple diagram into the world of human experience: a toy which none could own, and anyone with a stick and some dirt could instantly play with. It requires no manufacture — it cannot not be stolen or co-opted, and ‘giving it away’ causes the giver and the gifted to become ‘exponentially more wealthy’ — in ongoing progressions.“

As early mathematicians fleshed out new concepts, and invented new symbols to represent their discoveries, they were basically just skipping stones further down the stream, packaging ideas in ways that other humans would be able to recognize and access and build upon. Sometimes this was done in full public view, but often they worked in secret, because their bodies of work (as well as their actual bodies) were vulnerable to being dismantled by anyone who found them threatening.

The reason I chose to begin writing about the Tetractys this way was to highlight that there are many different forms of information, many forms of teaching, many forms of learning. And, as we have finally proven, the world is also full of different kinds of human intelligence, capable of many different things. We’re slowly digging out from preconceptions imposed on us by minds that were overly concerned with ideals; any deviations from the ideal were considered to be of lesser value, selected against.

That’s one consequence of hierarchical religious thinking, and it’s not hard to see how even the Tetractys — with its depiction of reality cascading downward from a perfected “monad” state to an earthly “tetrad” — could end up appearing to confirm earlier humans’ preconceptions about what human perfection ought to look like, sound like, be like. Contemplating the pure language of mathematics, or seeking the pure spiritual experience, we crave to reform ourselves and our world to reflect this pursuit.

Science and religion were conjoined for so long in our ancient history, it’s not surprising that notions conflating scientific purity and spiritual purity still turn up everywhere you look. We’re hooked on them! You see it a lot in New Age thought, and the desire to find confirmation of our spiritual beliefs in “natural” phenomena; the dreaded quest for “authenticy.”

I wanted to start by pointing out that I am not qualified to teach others in the formal sense. I have no accreditation. My academic pedigree is limited to... well, words written in a blog post, however thoughtfully I manage to string them together.

To learn tarot and other various practices, first I had to learn how to learn. For the most part, my education was missing this crucial step. I’ve always been quite naturally absorbent, but the moment my curiosity in any subject was satisfied, I considered my work done.

That’s probably how most people function when left to their own conclusions... unless survival dictates otherwise. But some of us discover we simply have to keep evolving, keep looking for answers, in order to endure. How do I adapt to survive in this world? What are its qualities? Where are its boundaries? What am I actually capable of?

Taking responsibility for my own education in the longer term is one of the greatest accomplishments in my life. I never thought so before; it’s been too easy to focus on everything I’m still lacking. But now that I’m looking back from my forties, I see a surprising amount of continuity and steady progress. By now I’ve also noted the way knowledge fades when it’s seldom-used, so that means I’m often stuck with the humbling, non-glamorous chore of re-learning everything that used to be right at my mental fingertips.

The Tetractys flickered in and out of my awareness back in 2009, and then lit up again years later when I was working on a series of instructional posts about the minor arcana cards.

This was the phase in my own practice when I began to leave the Tree of Life and other Qabalistic studies behind; the deeper I’d dug into them, the more I had to admit that my questions weren’t being answered — and in the meantime, I was being inundated with information that I had no practical use for. And as a non-Jewish person who reads and discusses the tarot quite often, I became uncomfortable relying on concepts related to the Hebrew alphabet that had been passed down by Western occultists.

At best, I had to admit that it was no longer helping me survive in this world.

Researching the overlapping history of the Tree of Life and the Tetractys, I realized this was a much firmer basis for my own personal investigations. The history of numbers and of symbolism has no direct path! But it’s very easy to end up sticking to the most well-trod path, even if it’s not going exactly where you’d hoped.

The Tetractys jewelry I created with Azamel was a way of marking that commitment with a reminder to keep learning, to question and refine my own interest in the subjects that appeal to me. I must be willing to adjust course, even if it means wandering through grass higher than my head. That feeling of ignorance and vulnerability is reminiscent of being child again, and comes with all of the wonder and discovery of childhood, as well as the requisite bumps and mistakes and redundancies.

In upcoming posts, I will share some of what I’ve learned from the Tetractys and how I’ve reinvested that into my tarot practice. I’m not “teaching” you how to use the Tetractys in your tarot practice, but I’m happy to help give the balloon another bump, and point to sources that might give you that delightful cascading sense of awareness.

By now I know many of you personally (even if just a bit!) and I know that our love of that feeling is one that knits us together. It also unites us with all the teachers and students of past traditions, many of whom made tremendous sacrifices just to be able to pursue and relive that feeling.

Thanks for reading! And special thanks to those who snapped up this bit of jewelry early on, it has meant the world to have SOME small thing to show for the long months sitting here in the vast semi-darkness of 2020. Developing the consecration ritual for the Tetractys jewelry, I felt almost like I was visiting people, imagining their surroundings, their cards, their questions.

It’s comforting to be surrounded by so many who are still searching, still learning. I do not believe this ever ends, even after death.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Augment against Zeno & Philosophical Absurdity

By: Alphacenturian4

Let’s talk about Zeno and Postmodernist. These two schools of thought have a few threads in common. One, they both find flaw with western logic, science, & philosophy. Second, they both find fault with the limits of human language and sense perception. Zeno lived from 430 to 490 BC, at the birth of western thought; and the postmodernist began with the rise of Heidegger, and Derrida, and they think we are witnessing the death of western civilization. And from that perspective, you could almost call this digital age of postmodernism, an age of post humanism, and that their generation will bring about the death of existentialism and modernity. See, both Zeno and the postmodernist are looking at the same “problem” from different points in time, the beginning of and the end of the patriarchal normative right. And to this problem, they say “no,” and reject the claim that “western-capitalist-democratic thought,” holds any objective truth. Both Zeno and the postmodernist are sticking out a tongue and pointing, saying, “That there are no universal objective truths, that there is only relative truth, subjective facts, and consensus.” Zeno and postmodernist are essentially trying to do the same thing, to undermined modernity (what we consider progress) at its foundation. The one place that Zeno and the postmodernist disagree, and what my argument cannot reconcile, is Pluralism.

Yet, even so, to me Zeno is a proto post-modernist. What I say today, is an argument against socialistic postmodernism; and an argument for logic, reason, and science. And though I will take jabs at them to prove my point, this is not an argument against atheism, nor feminism, for both of these ideas and movements can be based on reason and logic and can have moral and righteous goals. It is when these movements hit postmodernism that the mix becomes toxic and skepticism gets turned on those who wield it.

Let’s compare Zeno and postmodernist for a moment. Zeno defended Oneness and argued against logic, logos, mathematics, and science. While postmodernist protest for extreme pluralism and relative subjectivism, they promote narrative facts, magical thinking, and equality of outcome. Zeno was arguing against the foundations of western and modern thought. His targets of ridicule were Pythagoras, and Socrates, while his most vocal opponent was Aristotle. Current postmodernist are arguing against the consequences of democracy, capitalism, and western philosophy. They care more about emotions and feelings than logic and reason.

But now you might be asking, who was Zeno of Elea. Zeno was a pupil of Parmenides. It was Parmenides who defined the concept of the One, which Zeno famously defended. Zeno's paradoxes were designed to disprove or at least show the flaws in the popular ideas of his day, those of plurality and change. His arguments were on the flaws of perception and against the concepts of plurality, motion, and space. He argued for the idea that "being is one seamless unchanging whole," (Philosophic Classics) that reality is an illusion, and that real "change is impossible." (Philosophic Classics) The lesson that should be learned from Zeno’s paradoxes should not be that the institutions of realty are flawed and so must be dismantled but that there are discrepancies between philosophical theory and lived reality. To my mind, Zeno knew his paradoxes were absurd and that their implications were ridiculous. To me, at the end of the day, his arguments were merely intellectual exercises. You can see this by the claim that he was "two tongued" (Early Greek Philosophy) and that he would regularly argue both sides of a paradox.

This reaction to the limitations and failures of western civilization and thought can be seen as the internal thoughts of a teenage student when they come to realizations, about the world and reality, which contradict themselves. First, they are disgusted, realizing that their air is being re-breathed by the whole classroom; and that they have to inhale the same breath from a classmate that they hate. Then comes doubt, they find out about, particles, cells, and atoms. For what can be both solid and whole yet be porous and filled with empty space at the same time. They ask, “how can this be normal?” Next is fear, they find out that photons can pass through walls. That they are not safe from radiation, that their mothers, and fathers can’t protect them; that their very walls are illusions. Soon they feel anger, for the problem is worse than their parental figures, those pillars of strength, being weak, worse than their teachers and religious leaders, their authority figures being flawed. No, they find out that the very language they speak was made up and possibly by people who they disagree with, the words that they have to use to communicate with other humans are flawed, and incomplete. And finally, they’ve had enough, and they reject the entire institution. Here that institution is education, but you can switch in any that you like, religion, science, history, military, political, heck, civilization itself.

That the rules are made up by consensus blows their minds and destroys their reality. It is the same way many baby atheist leave religion. Because either their basic understanding of religion cannot handle the complexities and paradoxes (what they would call hypocrisies and contradictions) in adult faith; or because they never truly believed in the 1st place and when their faith was tested their doubts got the better of them. For there are stronger arguments against faith than the reactionary spite of an immature mind. It is when I was a deconstructionist and one of my best high school friends said, "But if we can break the speed limit then how it is really a law, it’s just made up."

In the end, it is the same old argument between deist and atheist. If nothing can be destroyed then how is it that we living people see things constantly and consistently end? To a modern person this would be a matter of science and perception. But to those of us with faith this supposed paradox never phases us. But there was another group silently listening to our argument, the postmodernist, and to them the argument itself was a sign of failure, the pain, and suffering that such an argument caused could not be allowed. They cried out “if they are arguing about what happens after we die then we must stop death.” While we were arguing about the existence of a soul or a god, the postmodernist were off creating their own language and with it their own new gods and idols. And it is language where they got us, for we could never admit to each other or ourselves that what you call energy we have always called the soul, chi, or ki. It was in the end a matter of terminology. And that brings us to the current Zenos in our midst.

And while sometimes these realizations bring about necessary and positive change, like the renascence and the enlightenment, sometimes they have negative pushback like the soviet revolutions in Russia, China, Korea, and Cuba. So today, we have a new revolution, a new pushback, with questions both sides of our dichotomy thought were settled long ago, that go down to the more fundamental way we view the world. How many genders? How many sexualities? How many races; nay species of humans? Well we can make the same arguments as Zeno, first let’s try his “there is only one.” Okay, one human race, for we are all Homo Sapien Sapien; one sex for we all start off as female in the womb, and we are all animal so there is no human. Oh dear, I hit my first paradox. For how can there be no human if I am one, how can there be no me if I am the one who is saying this? But alas, let’s continue this line of thinking to its end, let’s continue into absurdity, we now have to wipe out gender, sexuality, and, oh shit, there goes science.

But wait Zeno would argue the other side too. So let’s take it to the other extreme. Let’s take humans, and let’s say that each variation is something new; so if each gene can mutate 64 times per generation at 20,000 genes in a human animal, meaning there are now a million possible human species, whatever the threshold for a species might be. And, logically there are three sexes, male, female, and intersex; but wait what about all the variations in-between. And soon enough it all becomes unwieldy and the language means nothing. Opps, went too far the other way, and to hold on to any sense of identity each nation has become its own race, its own people, and then suddenly we regress to biblical and then prehistoric times. Where each tribe is fighting for a foothold for survival and eradicating your enemy is the only way to guarantee safety and victory.

And this is where the Aristotelian in me comes out. So, from my point of view, the solution remains in the middle. A comprise in language, a social contract with society, where we don't need absolutes to get things done, to accept that motion is real, to see things and recognize them as they are. Yes, words change, meanings change, laws change, and people evolve; but that doesn't mean these things don't exist. We are imperfect, we are incomplete. We label things as male and female and accept that some people are born intersex (but we also understand that the individuals who meet that criteria are rare) and we also understand that thanks to science people can transition from one sex to another.

That language is “good enough,” not because those terms are precise but because of their utility, they are true enough and easy to communicate. We accept that there are traffic laws, not because we can't go over the speed limit, but because we understand that as a society, we do not want people driving 50 mph through a neighborhood where children are playing. We understand the need for simplicity; we don’t add to the law all the reasons one might use to speed; a clear street, an emergency. We state the law and leave it alone to be interpreted, sometimes incorrectly, by those who are subject to it and by those who enforce it. Zeno and the postmodernist are wrong not because their complaints are invalid or unsound, but because their solution is.

References/Citations:

Philosophic Classics volume 1, Ancient Philosophy 4th edition, pgs 23 - 27, Forrest E Baird and Walter Kaufmann, Prentice Hall 2003.

Early Greek Philosophy, pgs 99 - 108, Jonathan Barnes, Penguin Classics 2001.

1 note

·

View note