#poetryonpoyntz

Text

Ave atque vale

For fifteen years, Jay and Barbara Nelson of the Strecker-Nelson Gallery have hosted Poetry on Poyntz, a semi-annual soiree for Manhattan lovers of literature. As the Nelsons prepare for retirement, Kansas State Professor Elizabeth Dodd reports on the final event, and reminisces about Poetry on Poyntz through the years.

Evenings With Jay And Barbara

Like a magic trick, Poetry (and short prose) on Poyntz emerged from beneath a white-linen tablecloth during a fundraising event at the Beach Museum of Art fifteen years ago.

Or maybe it was spilled across that tablecloth when somebody started waving her hands again.

Or maybe it slipped in the door without actually paying and sat down to eat the piece of Purple Pride cheesecake nobody had touched yet.

Or maybe it leapt from somewhere inside the Chihuly above the staircase, the Medusa-haired, prairie-fire tornado that hangs in its own light, every night, just past the museum’s arch.

Actually, Jay Nelson seemed to remember exactly what happened. He and Barbara Nelson, his wife and co-owner of the Strecker-Nelson Gallery, had been seated at the same table with me—the two of them conjured up the whole concept: an open mic event for literary artists, hosted in the most beautiful private gallery space between oh, probably St. Louis and Denver. I said yes, yes, please, yes, let’s do it! Ever since, twice a year, writers have gathered at 406 ½ Poyntz (sometimes 406 Poyntz, downstairs), surrounded by work from the region’s most prominent painters, sculptors, and ceramicists, to fill the space with literature, too.

Barbara and Jay’s connection to the English Department goes way back. Jay graduated from K-State with both a BA in English in 1971 and a MA in English in 1973. Barbara graduated with a BA in Social Sciences in 1971. They knew people like Brewster Rogerson, who was honored when alumni established a scholarship in his name. They tell stories of evenings spent in professors’ living rooms, reading Shakespeare aloud, drinking wine and dressed in hippie-wear.

Literature and faces, readers and authors. So they opened the door at the bottom of the stairs and invited us all inside, year after year. And we came.

Before he left for KU to chase down a PhD, Ben Cartwright kept showing up with a bullhorn. He didn’t read everything through it, and you couldn’t always tell why he chose to blare the lines he did and skip the others, but it was very cool and even after he left Manhattan, once or twice he came back, dragging the bullhorn with him along I-70 because, well, Lawrence wasn’t cool enough.

Sea Sharp (we knew her then as Cherry Sharp) and Michael Mlekoday performed their poems, spoken with the same back-beat syncopation and driving rhythms that took the stage at Auntie Mae’s Mighty Fine Poetry Night downstairs in Aggieville. (Both poets later collected some of these pieces in their first-published books. We knew them when!)

Erin Billing and Anita (Berg) Mihalic read poems of their own but usually not before cracking the spine of a favorite book and choosing some beloved classic to share. Read someone else’s work along with your own and you’re making the room a portal leading into everything you’ve ever loved.

Michael Verschelden broke our hearts with poems of his parents’ cancer, the crystalline fragility of passing time.

Once or twice, the Jabberwock showed up in the person of Rachel Moore who went galumphing back and forth across the floor. And Matt Groneman performed James Brown. James Brown!!!!

(Then Dan Hoyt flashed his typesetter’s tattoo, asked nicely, and PoP metamorphosed into PaSPoP, which has more letters and looks good on the page but no one can pronounce it.)

People read scenes, paragraphs, dialogue. Peter Williams did that. (And he was really tall.) Cormac Badger did as well, but sometimes he switched to poems and once he Jackie Channed. He verbed.

Kylie Kinley read snippets of essays so funny we thought she would laugh, herself, but she never did. The trip to Italy and the missed train and the beach and the underwear—it all came out joyful and absurd and then someone got up to go the bathroom as soon as the story was over.

Season after season, who gathered in the warm light, drank beer or didn’t, read aloud or didn’t, almost knocked into a piece of art but didn’t. We didn’t think it could ever end: we didn’t.

But last month was the last. The chairs faced west, looking at a painting of a European goldfinch and another of a child in a party hat with ducks flying past the 1950s television set.

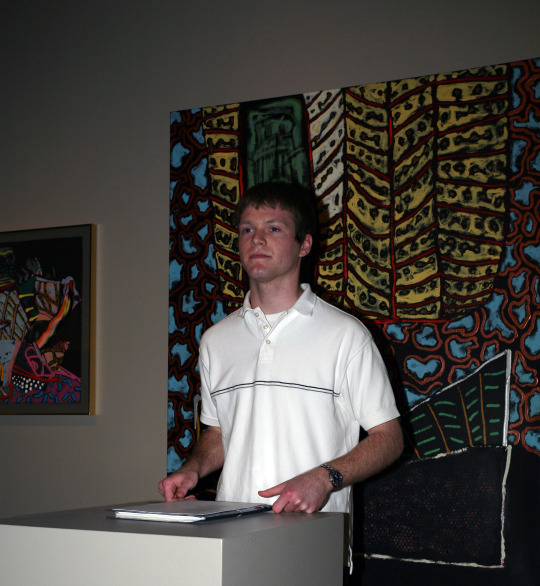

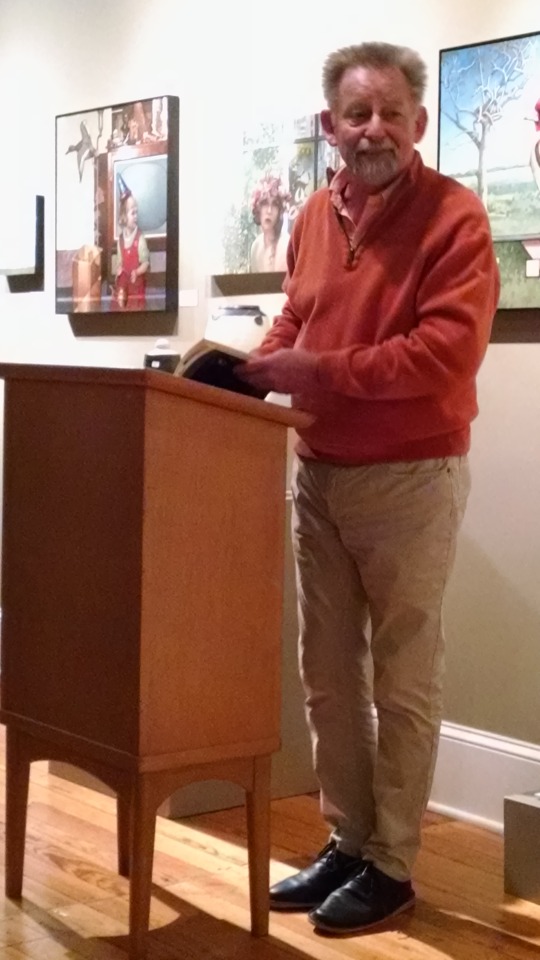

Jay stood at the podium, a real podium, antique oak—they’d found it in the alley out behind the building, dragged it in, and for the first time we wouldn’t stand beside the blond-wood pedestals that usually held a wild pitcher morphing into some undiscovered toadstool, or a cross between a teapot and a giraffe. We had a podium. The first time; and the last. Jay told us how the gallery is changing hands: Barbara and he are retiring and have found buyers for the business and the gallery will still be there but there won’t be nights like those again, with the dachshund, Artie, click-click-clicking her toes between the chairs. I wanted to cry.

(But I’ve been near tears every day since mid-November, so there’s that.)

Like always, one by one, the readers rose. I used to think it was like a Quaker’s Meeting—stand and speak whenever you’re moved to do so—one after another, coming up front to read from paper printouts, or a notebook, or (how do they DO that??) from their phones.

When Deborah Murray read her sestina, an elegy called “Cowley County Fairgrounds,” she counted out the end rhymes for us like a six-point star—rain, wait, cold, play, darken, wind—and then the poem spread out behind the fingers of her counting hand, a comet’s tail blown back behind its distant orbit.

…down another decade--a bleak and cold

scenario you wish you could rewind,

revise, recast, rather than just wait

for the lingering pain to end, just wait

for her death. This vision is not playful;

it's a vigil. Watching her life wind down,

you see the sky lighten and darken.

But Robert Sanders wound it up again; he read a boxy, prosey, road-wander in Kansas, the story of a highway and a bike, the horizon and the handlebars—ape hangers, he called them, though he held the little podium like a child’s toy between his hands. (“I really liked the biker-dude,” one of my students later told me.)

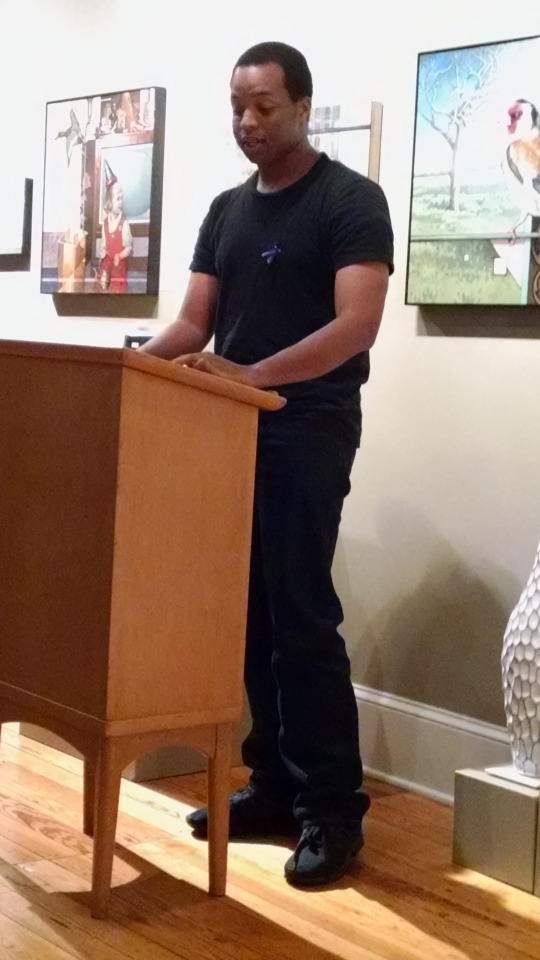

And Ronald Atkinson read prose as well. “The General’s Address,” his story was called, and he held his paper as if he were outdoors instead of in, as if we sat in the open cold and the wind threatened to lift the general’s speech and carry it away.

Brian McCarty read what he called ditties. Nope. The characters that stalk his poems will never settle down into anything that bland or dull. Ian Sinnett read what he called poems, and they were, lyric pieces against the foil of narrative.

Brennan Bestwick read his poem “The Howling Rain,” one of his surprisingly surreal intrusions into the heartland, and I remembered at the Farewell Reading, back at Arrow Coffee, Robert booming at him from across the room READ THEM LOUDLY, BRENNAN, and him answering I WILL DO THAT, ROBERT, but that was another time and place.

Katy Karlin thanked our hosts. Ladies and Gentlemen! But for the moment she wasn’t Dr. Karlin, she wasn’t Katy at all: She became James Joyce’s Gabriel giving his formal toast at a party in Anglo-philic, high society Dublin. Ladies and Gentlemen. It is not the first time that we have gathered together under this hospitable roof…

It was not the first time.

Barbara Nelson read us “Summer Evening,” a prose-poem or a tiny memoir by Carolyn Miller, from her favorite journal, The Sun.

Nothing has happened to me yet: not baptism, adolescence, going away to college. I have not managed to slip away from this place forever….and as the sky outside grows darker, the lights of passing cars and the windows in the other houses on the hill grow brighter, until the lights go off one by one, and we fall asleep, not knowing that someday none of us will be able to return, not even a moment, to tell each other what it meant that we were once here together, and alive.

And I realized, this is how I’ll always remember Poetry and Short Prose on Poyntz:

First, a mosaic of faces and sentences, each individual and episodic, each abstracted from the general joy.

Next, the long, suspended moment, the magical hour that stretches, sometimes, well beyond an hour, those floor-to-ceiling windows and a familiar, elevated view.

0 notes