#sasha and farah's child!

Text

#actually. baby boi in the fleshh whewww#sasha and farah's child!#im so down bad send help#his sister is coming soon 😈#aubrey.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

ERAS ☔️🌟🧚🏼♀️🍄✨👑🦄💓🐞🪞💃🏼👩🏽🎤💋

Eras are important to some artists growth , and it brings that excitement ,especially with a pop star 💫 they are the most likely to do this , when a new album comes along we see this new side , the villain era /arc , and how it becomes a thing ,or the leave yh past behind and become a whole new person , which during certain period s fast so they go for a relationship and then they become a new person, or we have the error where they are in a relationship and we don’t we get the blank period of where they are too deep in the relationship then the relationship ends and then we get some of the best tracks we’ve ever heard talking about you, Amy Winehouse with “back to Black “and “Frank”,

I’m not a big Taylor Swift fan at all in fact I only know like two of her songs and I am a millennial. I’m born the year after Taylor but I do know of her work and her artist history and I do believe she’s very talented. she’s talented because she’s a good songwriter, but she’s also talented at reinventing herself Wasn’t so much I don’t believe all artists do it to some degree even though heavy metal artist that’s not forget people like Pantera, massive group heavy metal, reinvented them at the beginning they were Glamrock and then when Phil anselmo, join the fold they got rid of the whole Glam thing that dime bag had going on.

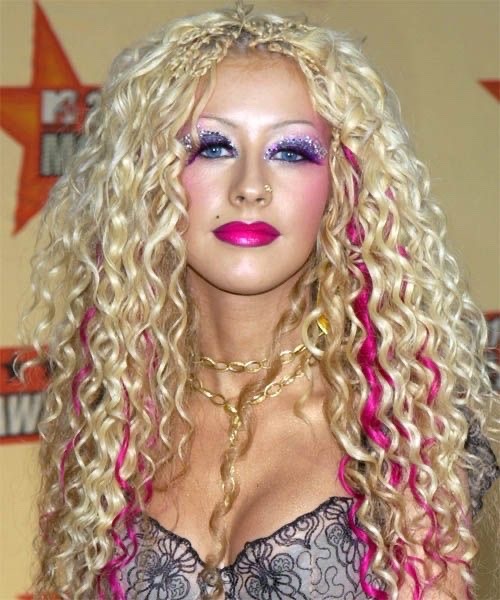

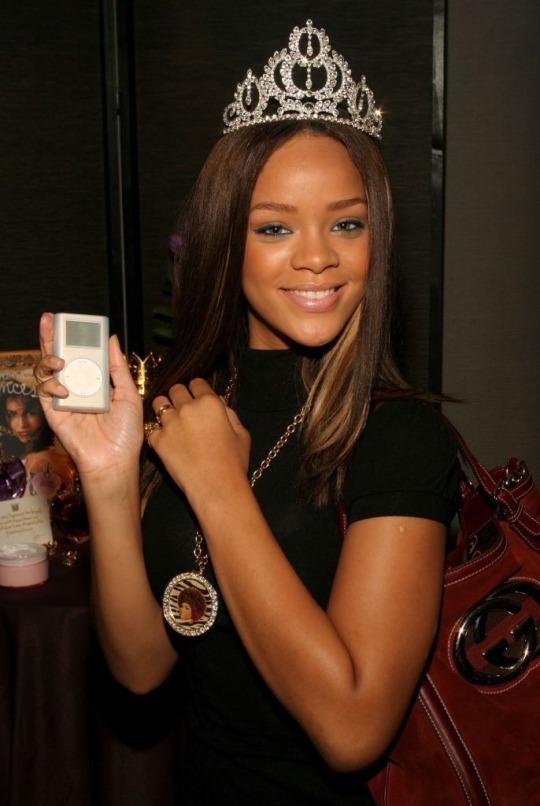

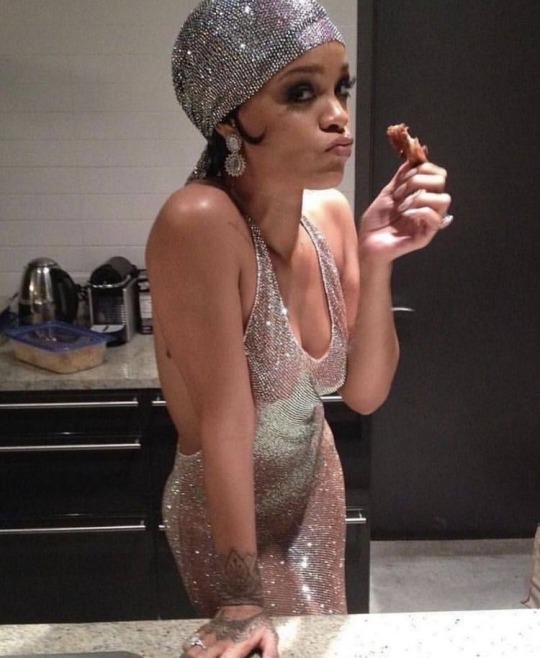

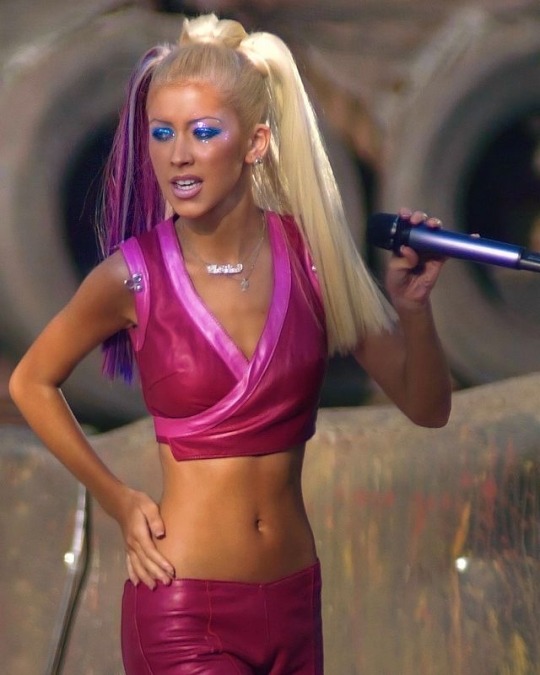

I have put two of the artist who I think I’ve best at doing this trick which is Rihanna and Christina Aguilera. Christina did it going good go gone by originally before in the early 2000s and the late 90s, because she had to market herself in a completely different way to Brittany like a lot of girls did in the 90s she was like right I have to be the bad girl now, and I feel like you see this lady marmalade, her dress with her hair make up, have fun too. Don’t get me wrong and Brittany is amazing dancer but her ear is once so change as Christine and Rhianna.,

Beyoncé from Destiny’s Child(with all the God knows how many trust me I know all the members I was a huge fan. It was one of my first autism sessions so I know it was Latvia Latoya Farah and Michelle., and then Farrell left and it was just Michelle and it was 3, definitely the best of this was for another great person and I didn’t even think putting in this category with Michael Jackson. He had the best selling album of all time with thriller the first album which was disco off the wall., R&B , BAD pop mixed with R&B, DANGEROUS POP ROMANTIC AND ROCK,

But I love the reinvention of these popstars and how they do it. Let me think of my favourite examples here my favourite I did yesterday it was loud with Rihanna., Beyoncé with her 2011 album and her 2006 album, Sasha and Sasha I will do the alters..

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A sequel to this post, but this time its a comparison of Rosie / LI’s youngest children bc im still on a fankid kick

Loreley (Rosie / Julian): Honestly just looks like SJP as sarah sanderson roflmao. She’s got the strongest magical abilities out of the 3 siblings, especially with enchantments and illusions. She has a special bond with the raven flock that lives in the barn (Malak has had his own family), and has drawers upon drawers of trinkets they’ve gifted her that she makes into charms and talismans. She’s closer with Gideon than she is with Laoise, but that’s mostly from the age gap between them. Loreley is on the spectrum and is selectively mute, she usually communicates via her older brother.

||

Sarnai (Rosie / Muriel): Clever, sharp tongued, and a bit of a trickster. Sarnai is very passionate about the history and culture of the Kokhuri people, and as an adult they work as the curator of the museum, and regularly travel south to organize festivals. Very close with their older brother, Willow, and may or may not encourage him to get into fights at the tavern lmao (brawn + brains duo). Very skilled in scrying and runic magic, but is often overconfident in their abilities or is just plain lazy with their magic. Fun fact, they’re the only one out of the five children to get Rosie’s pale hair color.

||

Pierrot (Rosie / Portia): Adopted after his family’s ship wrecked along the coastline. Shyer and more reserved than Sasha and Angelo, definitely was the one to stay inside and read while his siblings were outside playing. He has a natural talent for wind and sea based magic, though his true love is cartography. Despite having only barely survived a shipwreck as a child, he loves sailing and was always the first on the boat whenever the family went on trips. Portia and Rosie used to call him their “little pirate”

||

Farah and Zarah (Rosie / Asra): Gemini twins trope to the MAX. Zarah is older by about 15 minutes and never lets her brother forget it. Farah is, unfortunately, the only jock in a family of art kids lmao. He’s very sweet, though he does like to play pranks. Zarah is cooler and more calculated, and isn’t quite as outgoing (Has a lot of acquaintances, but few actual friends.). She loves to gossip, though. Her focus of magic is on enchanting, and she makes candles for the shop with her older brother, Jericho. Zarah is the shortest of the family. The magic gene seems to have skipped over Farah, something commonly observed in twins. (one has magic and the other has none, or both are incredibly powerful)

#rosie#fankid stuff#long post#I need to draw them all so bad#i esp love the vision i have for Zarah she has very stylish glasses and always has a sprig of lavender in her hair#also has a python familiar. haven't decided if its related to Faust or not#Pierrot is my second fav tho even in his like 20s he looks like an overgrown sad victorian child

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

For Whom the Cell Trolls

A new book argues that modern wars will be won with phones and laptops rather than tanks.

By Sasha Polakow-Suransky, Foreign Policy, February 28, 2018

War in 140 Characters: How Social Media Is Reshaping Conflict in the Twenty-First Century.

David Patrikarakos, Basic Books,

320 pages, $30, November 2017

It’s popular these days to proclaim that Clausewitz is passé and war is now waged via smartphones and Facebook feeds. Few writers have actually explored what this means in practice. The journalist David Patrikarakos’s new book, War in 140 Characters, chronicles in granular detail how social media has transformed the way that modern wars are fought. From the battlefields of eastern Ukraine to the bot factories of St. Petersburg, Patrikarakos takes us into the lives of ordinary citizens with no military training who have changed the course of conflicts with nothing more than a laptop or iPhone.

At the core of Patrikarakos’s book is the idea that narrative war has become far more important than physical war due to new technologies that shape public perceptions of conflicts in real time, regardless of what is actually happening on the battlefield. The spread of social media, he argues, has brought about a situation of “virtual mass enlistment” that gives civilians as much power as state propaganda machines--and sometimes more. Although some techno-utopians have celebrated the breakdown of centralized state control of information and the empowerment of the individual to challenge authoritarian regimes, he is not starry-eyed about the leveling of the playing field. “[B]ecause these new social media forums are structurally more egalitarian,” he writes, “many delight in holding up the Internet as the ultimate tool against tyrants.” It is not. As Patrikarakos notes, “the state will always fight back”--and it has.

The greatest strength of War in 140 Characters is the author’s preference for in-depth reporting over soundbite-ready platitudes. This is not a book of Lexuses and olive trees. Patrikarakos also goes to great lengths to show both sides of each conflict he covers. His chapter on Israel’s 2014 war against Hamas in Gaza, known as Operation Protective Edge, first brings us into the home of Farah Baker, a 16-year-old Twitter activist who became the voice of Gaza during the Israeli bombing campaign. Patrikarakos shows convincingly how Baker “could morph from a mere child into the most potent of weapons.” She helped drive the narrative of the war by producing heart-rending eyewitness accounts of a city under attack and disseminating information that mainstream news organizations, lacking access to the battlefield, picked up and repeated in their own coverage. Mainstream journalists had “become, in effect, her PR agents.” While Palestinians’ “rockets could never stop Israel,” he observes, “their narrative might.” Some books, content with celebrating a heroic underdog, would stop here. Patrikarakos’s does not.

Instead, he takes us into the inner sanctum of the Israel Defense Forces and examines how the Israeli defense establishment adjusted, slowly, to fighting a new enemy and a narrative war. He profiles a young soldier who, during a previous war in Gaza, pushed her superiors to stop fighting “analog war” and started a YouTube channel and Twitter account to disseminate the IDF’s narrative. The soldier even paid for a blog and domain name on her own credit card to bypass the grindingly slow bureaucracy. By 2014, the top brass had joined the modern era, and the IDF’s Facebook page was using visual propaganda, primarily videos, to bolster its message. The problem for Israel, as Patrikarakos observes, is that it is in a lose-lose situation even when it defends its narrative using the latest technology. “If it struck Hamas targets embedded in civilian areas, it received international condemnation, but if Hamas succeeded in kidnapping or killing any of its soldiers, Hamas won again.” The state struck back effectively, but the narrative of the underdog still dominated the news cycle.

The book’s focus then shifts from Gaza to Ukraine, where we meet Anna Sandalova, a middle-aged mother and former PR executive who is appalled by the state of the corrupt Ukrainian military establishment, hollowed out by years of kleptocracy and unable to provide the basic necessities for its soldiers. She takes it upon herself to “fill the governmental void.” She starts by organizing her friends on Facebook to supply Ukrainian soldiers battling separatists and Russian troops in the country’s east. Soon, she is sourcing boots and body armor and driving to the front lines in subzero temperatures, where Patrikarakos joins her under the threat of artillery fire, to deliver the supplies. Her efforts are not entirely new; as the author observes, the Jewish Agency illicitly obtained and shipped weapons to the Haganah--Israel’s pre-independence militia. The difference between 1948 and 2016, Patrikarakos argues, is that “What it may have taken the Jewish Agency months to do, Anna can do in days” with the help of diaspora networks that can be instantly activated on Facebook.

Just like the Gazan teenager tweeting under fire, the Ukrainian citizens fighting via Facebook also faced a response from the state. In this case, it was Russian troll farms that countered grassroots activists like Sandalova. Patrikarakos tells the story of Russia’s state-sponsored trolls by profiling one of them, who worked at the center of the counterpropaganda effort during the early stages of Russia’s war in Ukraine. Rather than simply justifying its actions, the Kremlin’s goal was to flood the zone with conflicting information and “sow as much confusion as possible.” The troll and his colleagues created fake blogs and sites masquerading as Ukrainian and cited each other as genuine sources in a self-referential circle of lies, producing a narrative completely at odds with the reality on the ground that was enthusiastically consumed and shared by pro-Russian separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk. The troll rationalized his work as “finding idiots and giving them what they wanted.” The mark of victory in Russia’s new narrative war was not to convince the enemy of its position, but to heighten the level of doubt about all news among the target population so as to “weaken their propensity to recognize the truth when they see or hear it.”

Patrikarakos argues that social media exerts both a centripetal force--uniting people and creating new virtual communities such as the Ukrainian patriots who donated to Sandalova’s Facebook page--but also a centrifugal force driving people apart, such as the Ukrainian neighbors (or for that matter American Democrats and Republicans) who live side by side but inhabit parallel universes because their news comes from diametrically opposed sources. It is a textbook illustration of Hannah Arendt’s classic description of the fertile soil in which totalitarianism grows: “The preparation has succeeded when people have lost contact with their fellow men as well as the reality around them,” she wrote in 1951. “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thoughts) no longer exist.”

0 notes