#solidarity with all film and television workers struggling for their rights

Text

[id: a graphic of a clapperboard overlayed with the words "I.A.T.S.E. We Stand Together #IASolidarity"]

Unless an Agreement is Reached, IATSE film & tv workers will begin a nationwide strike on Oct. 18 at 12:01 a.m. (PDT)

#iasolidarity#iatse#iatsesolidarity#barry hbo#just to make clear where i stand on this#solidarity with all film and television workers struggling for their rights#i saw people being angry barry got delayed bc of covid restrictions#i better not see yall repeat that bullshit over this if a strike happens

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

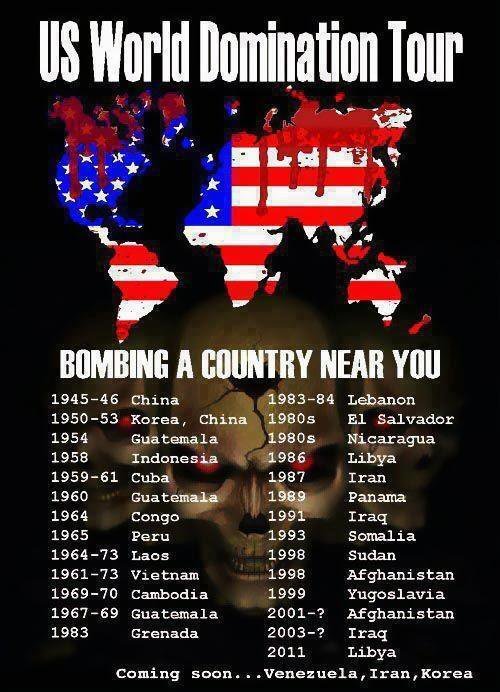

I Never Saw a World So Fragmented!

It is amazing how easily, without resistance, the Western empire is managing to destroy “rebellious” countries that are standing in its way.

I work in all corners of the planet, wherever Kafkaesque “conflicts” get ignited by Washington, London or Paris.

What I see and describe are not only those horrors which are taking place all around me; horrors that are ruining human lives, destroying villages, cities and entire countries. What I try to grasp is that on the television screens and on the pages of newspapers and the internet, the monstrous crimes against humanity somehow get covered (described), but the information becomes twisted and manipulated to such an extent, that readers and viewers in all parts of the world end up knowing close to nothing about their own suffering, and/or of the suffering of the other.

For instance, in 2015 and in 2019, I tried to sit down and reason with the Hong Kong rioters. It was a truly revealing experience! They knew nothing, absolutely zero about the crimes the West has been committing in places such as Afghanistan, Syria or Libya. When I tried to explain to them, how many Latin American democracies Washington had overthrown, they thought I was a lunatic. How could the good, tender, ‘democratic’ West murder millions, and bathe entire continents in blood? That is not what they were taught at their universities. That is not what the BBC, CNN or even the China Morning Post said and wrote.

Look, I am serious. I showed them photos from Afghanistan and Syria; photos stored in my phone. They must have understood that this was original, first hand stuff. Still, they looked, but their brains were not capable of processing what they were being shown. Images and words; these people were conditioned not to comprehend certain types of information.

But this is not only happening in Hong Kong, a former British colony.

You will maybe find it hard to believe, but even in a Communist country like Vietnam; a proud country, a country which suffered enormously from both French colonialism and the U.S. mad and brutal imperialism, people that I associated with (and I lived in Hanoi for 2 years) knew close to nothing about the horrendous crimes committed against the poor and defenseless neighboring Laos, by the U.S. and its allies during the so-called “Secret War”; crimes that included the bombing of peasants and water buffalos, day and night, by strategic B-52 bombers. And in Laos, where I covered de-mining efforts, people knew nothing about the same monstrosities that the West had committed in Cambodia; murdering hundreds of thousands of people by carpet bombing, displacing millions of peasants from their homes, triggering famine and opening the doors to the Khmer Rouge takeover.

When I am talking about this shocking lack of knowledge in Vietnam, regarding the region and what it was forced to go through, I am not speaking just about the shop-keepers or garment workers. It applies to Vietnamese intellectuals, artists, teachers. It is total amnesia, and it came with the so-called ‘opening up’ to the world, meaning with the consumption of Western mass media and later by the infiltration of social media.

At least Vietnam shares borders as well as a turbulent history with both Laos and Cambodia.

But imagine two huge countries with only maritime borders, like the Philippines and Indonesia. Some Manila dwellers I met thought that Indonesia was in Europe.

Now guess, how many Indonesians know about the massacres that the United States committed in the Philippines a century ago, or how the people in the Philippines were indoctrinated by Western propaganda about the entire South East Asia? Or, how many Filipinos know about the U.S.-triggered 1965 military coup, which deposed the internationalist President Sukarno, killing between 2-3 million intellectuals, teachers, Communists and unionists in “neighboring” Indonesia?

Look at the foreign sections of the Indonesian or Filipino newspapers, and what will you see; the same news from Reuters, AP, AFP. In fact, you will also see the same reports in the news outlets of Kenya, India, Uganda, Bangladesh, United Arab Emirates, Brazil, Guatemala, and the list goes on and on. It is designed to produce one and only one result: absolute fragmentation!

***

The fragmentation of the world is amazing, and it is increasing with time. Those who hoped that the internet would improve the situation, grossly miscalculated.

With a lack of knowledge, solidarity has disappeared, too.

Right now, all over the world, there are riots and revolutions. I am covering the most significant ones; in the Middle East, in Latin America, and in Hong Kong.

Let me be frank: there is absolutely no understanding in Lebanon about what is going on in Hong Kong, or in Bolivia, Chile and Colombia.

Western propaganda throws everything into one sack.

In Hong Kong, rioters indoctrinated by the West are portrayed as “pro-democracy protesters”. They kill, burn, beat up people, but they are still the West’s favorites. Because they are antagonizing the People’s Republic of China, now the greatest enemy of Washington. And because they were created and sustained by the West.

In Bolivia, the anti-imperialist President was overthrown in a Washington orchestrated coup, but the mostly indigenous people who are demanding his return are portrayed as rioters.

In Lebanon, as well as Iraq, protesters are treated kindly by both Europe and the United States, mainly because the West hopes that pro-Iranian Hezbollah and other Shi’a groups and parties could be weakened by the protests.

The clearly anti-capitalist and anti-neo-liberal revolution in Chile, as well as the legitimate protests in Colombia, are reported as some sort of combination of explosion of genuine grievances, and hooliganism and looting. Mike Pompeo recently warned that the United States will support right-wing South American governments, in their attempt to maintain order.

All this coverage is nonsense. In fact, it has one and only one goal: to confuse viewers and readers. To make sure that they know nothing or very little. And that, at the end of the day, they collapse on their couches with deep sighs: “Oh, the world is in turmoil!”

***

It also leads to the tremendous fragmentation of countries on each continent, and of the entire global south.

Asian countries know very little about each other. The same goes for Africa and the Middle East. In Latin America, it is Russia, China and Iran who are literally saving the life of Venezuela. Fellow Latin American nations, with the one shiny exception of Cuba, do zero to help. All Latin American revolutions are fragmented. All U.S. produced coups basically go unopposed.

The same situation is occurring all over the Middle East and Asia. There are no internationalist brigades defending countries destroyed by the West. The big predator comes and attacks its prey. It is a horrible sight, as a country dies in front of the world, in terrible agony. No one interferes. Everybody just watches.

One after another, countries are falling.

This is not how states in the 21st Century should behave. This is the law of attraction the jungle. When I used to live in Africa, making documentary films in Kenya, Rwanda, Congo, driving through the wilderness; this is how animals were behaving, not people. Big cats finding their victim. A zebra, or a gazelle. And the hunt would begin: a terrible occurrence. Then the slow killing; eating the victim alive.

Quite similar to the so-called Monroe doctrine.

The Empire has to kill. Periodically. With predictable regularity.

And no one does anything. The world is watching. Pretending that nothing extraordinary is taking place.

One wonders: can legitimate revolution succeed under such conditions? Can any democratically elected socialist government survive? Or does everything decent, hopeful, and optimistic always ends up as the prey to a degenerate, brutal and vulgar empire?

If that is the case, what’s the point of playing by the rules? Obviously, the rules are rotten. They exist only in order to uphold the status quo. They protect the colonizers, and castigate the rebellions victims.

But that’s not what I wanted to discuss here, today.

My point is: the victims are divided. They know very little about each other. The struggles for true freedom, are fragmented. Those who fight, and bleed, but fight nevertheless, are often antagonized by their less daring fellow victims.

I have never seen the world so divided. Is the Empire succeeding, after all?

Yes and no.

Russia, China, Iran, Venezuela – they have already woken up. They stood up. They are learning about each other, from each other.

Without solidarity, there can be no victory. Without knowledge, there can be no solidarity.

Intellectual courage is now clearly coming from Asia, from the “East”. In order to change the world, Western mass media has to be marginalized, confronted. All Western concepts, including “democracy”, “peace”, and “human rights” have to be questioned, and redefined.

And definitely, knowledge.

We need a new world, not an improved one.

The world does not need London, New York and Paris to teach it about itself.

Fragmentation has to end. Nations have to learn about each other, directly. If they do, true revolutions would soon succeed, while subversions and fake color revolutions like those in Hong Kong, Bolivia and all over the Middle East, will be regionally confronted, and prevented from ruining millions of human lives.

1 note

·

View note

Text

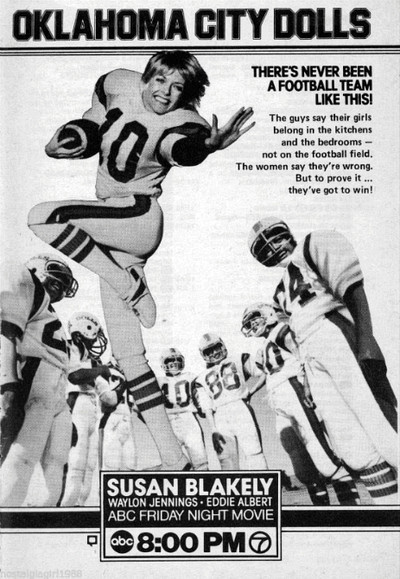

Why ‘The Oklahoma City Dolls’ is the best sports film of all time

A huddle in Oklahoma City Dolls (1981). | Oklahoma City Dolls/Sony Pictures Television

Clichés get new weight when they’re about equality.

The best sports film of all time is a 1981 made-for-TV movie called The Oklahoma City Dolls.

This is not an assertion made lightly. Sports have inspired countless memorable films, and I, for one, certainly can’t profess to have seen them all. Nevertheless, it’s hard to imagine that any of the others tell as smart — and as progressive — a story as the mostly-forgotten Dolls, which you can only currently watch via YouTube bootlegs.

Name another movie that articulates class struggle via a group of blue-collar women fighting to form their own football team, complete with thoughtful, but not forced, discussions of gender politics and labor rights. In that light, Waylon Jennings’ on-screen debut as the befuddled love interest is just the icing on the cake.

Photo by Walt Disney Television via Getty Images

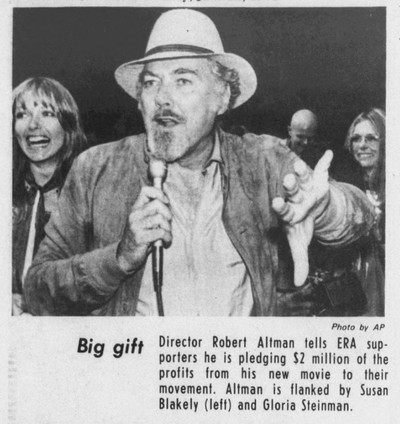

“It held up better than we would have thought,” says Susan Blakely, 71, who starred as Sally Jo Purkey — a disgruntled factory worker turned quarterback. She and her 76-year-old husband Steve Jaffe, who was among the film’s producers, watched the movie for the first time in almost 40 years before speaking with me. The couple had done Dolls as part of a three-picture deal Blakely had signed with ABC after the success of miniseries Rich Man, Poor Man (for which Blakely won a Golden Globe). “They gave us a bunch of scripts, and I thought this one was just terrific,” she adds.

The movie, which was written by Ann Beckett, is loosely based on a real team. The Oklahoma City Dolls were a semi-pro team that played for three years in the late 1970s, as part of a larger vogue for women’s football during that period. Though the Hollywood version, produced in part by an all-women company called Godmother Productions, is heavily fictionalized, the liberties taken make the Dolls’ story more — not less — controversial. The team’s battle to get on the field serves as both a broad metaphor for equality and an allusion to a specific, timely fight.

“I was very political,” Blakely says. “That was what attracted me to the script.” She’s been outspoken since her days as a model in the early ‘70s, when she organized the “Models for McGovern” group — “Ford [Models] was furious,” she says, laughing — and had a particular interest in women’s rights. “I was definitely a feminist,” she adds, in case you couldn’t tell as much from the picture of her onstage alongside Gloria Steinem.

A 1978 clip from the Ithaca Journal.

Blakely had spent much of the late 1970s pushing for the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment — a period that coincided with her greatest visibility thanks to Rich Man, Poor Man. When Cosmo asked her, “What’s your worst fear?” in 1980, she quipped, “That the Equal Rights Amendment will pass and we’ll elect our first woman president and vice president: Phyllis Schalafly and Anita Bryant.” Oklahoma City Dolls was filmed that same year, when the bill’s passage before the revised 1982 deadline was looking less and less possible.

An ad that appeared in TV Guide for the movie.

The movie begins with Purkey, a single mother working the line at a valve factory (they filmed in a real factory) for $40 a week, goofing around with her female coworkers. Where are the men? Well, they’re out playing for the company football team — which they get time off to do, while the women have to “pick up the slack” back at the factory with no extra pay. “You know what I’ve always said about you?” the middle manager tells Purkey when she has the audacity to have a conversation with a colleague. “You’ve got no company loyalty.”

As it turns out, her lack of loyalty should be the least of his concerns. Purkey files a complaint about the unequal conditions with the EEOC, and because the company is a potential government contractor, the agency takes it seriously. An official shows up and tells the boss they’ll have to give the women equal time off.

The boss, Mr. Hines, thinks he’s got it all figured out when he tells the women on the factory line that the only way they can get time off is if they play football, too. The trouble starts (for him, at least) when they take him up on that offer.

It’s not an easy road for the women, but you can probably guess where it ends. The strength of the dialogue, though, turns what might have easily been trite into a piece that’s quite powerful. After their first attempt at a practice, for example, the women are discouraged: it’s hard, and they’re already facing resistance from the men in their lives. “I’m afraid Ray’s going to kill me if he finds out,” the most promising wide receiver says quietly.

But Purkey’s response to the general dismay isn’t just a pep talk — it’s practically a consciousness-raising.

“The problem ain’t in our muscles, it’s in our heads!” she shouts, clutching her own in her hands. “There’s no reason on this Earth that a bunch of women can’t learn to run a ball back and forth between four goal posts just as easily as a bunch of men! Heck, I used to play football when I was a kid and I was pretty good too! Baseball, basketball, kickball — you name it! I loved all that stuff, until one day some adult told me it wasn’t feminine. That a woman has to act like a lady, flouncing around.

“Seems to me now that giving birth to babies ain’t particularly ladylike,” she continues, to chuckles around the room. “And making love ain’t necessarily ladylike,” Purkey adds as the women whoop.

“So what’s wrong with a little football, eh?”

Oklahoma City Dolls/Sony Pictures Television

Sally Jo (Susan Blakely) tells it like it is in Oklahoma City Dolls.

That scene was one Blakely says she tweaked to better reflect her own experience. When they were just a week or so into filming, the Screen Actors Guild went on strike — so she had six weeks to work on both her football prowess with the assistance of Jaffe, who had played in high school, and to revise some of her scenes.

“That was a scene that I worked on the most of any of them,” she recalls of the “ladylike” monologue. “I played a lot of sports as a kid — I was a gymnast, a runner, a swimmer, a tennis player, a golfer. I did try and play a little football with my older brother, but he was like, 6’10 when he was 13, and he would only play tackle. Anytime I’d get the ball, my brother would come right at me.

“But my father would always say, ‘You don’t have to win all the time when you’re playing against the guys. I would be like, ‘Well, then why are you even telling me to get better at it at all?’”

Blakely translated that feeling — the acute sense of unfairness women and girls face in sports, and beyond — into the scene, and most of the movie. Even though she says regrets coming off “a little too angry,” she’s just as frustrated now by the fact the injustices shown in the film haven’t been resolved. “We’re still dealing with women getting less money for the same jobs,” she points out. The Equal Rights Amendment still hasn’t been passed.

During the six-week strike, Blakely found herself mirroring Sally Jo: The women who had been cast as football players were crammed in hotels near the Columbia backlot where they were filming, seemingly six to a room as Blakely recalls it, with no cars. “I wouldn’t go on shooting until they got them two to a room, and cars,” she says. “I became like my character. Persona non grata at Columbia but …”

Oklahoma City Dolls/Sony Pictures Television

Sally Jo (Blakely) steps back to pass in Oklahoma City Dolls.

She and the other actors had to learn football, although a male stunt double handled Purkey’s play in the game scenes. The stunt coordinator, Allan Graf, was himself a retired football player — he started on USC’s undefeated 1972 team, and briefly signed with the Rams. He would go on to manage stunts for just about every memorable football movie, including Any Given Sunday, The Waterboy, The Replacements, Jerry Maguire and Friday Night Lights.

Jaffe himself had toyed with the idea of doubling Blakely on the field just to get a chance to play again, but ultimately decided against it. Like Blakely, though, he has fond memories of his time on set. “The idea that I would watch two full-fledged women’s teams playing against each other was phenomenal,” he says now — offering nearly the opposite perspective to Jennings’ character in the movie, whose skepticism compels Purkey to direct one of her signature barbs his way: “If you can’t hack being a quarterback’s boyfriend,” she tells him on a date, “I suggest you go find some frilly little thing who stands around in the kitchen all day and doesn’t embarrass you. I hope she bores you to death.”

“Having my wife be the quarterback was really wonderful to watch,” Jaffe adds. “To see her blossom as a real quarterback … We would throw the ball around in the backyard, and she got better and better at pinpointing her shots.

“One time she actually ran me right out of the backyard and into our Jacuzzi,” he recalls, and they both dissolve into laughter.

The warmth with which they remember Dolls’ filming is echoed on screen, populated almost exclusively by women who find enormous camaraderie in solidarity — and sports. It’s a story about plucky underdogs triumphing on the field, yes, but with bold and very nearly intersectional takes on all the unfairness happening off it. By the end of the film, a neighbor woman has named her newborn baby Sally Jo, and frankly, it’s easy to understand why.

0 notes

Text

How The 2010s Crystalized Women’s Anger

Amanda Edwards / FilmMagic

NEW DELHI, India — As a woman in my twenties who grew up in India — a country where abuse of women has been described as the biggest human rights violation on Earth — the SlutWalks of 2011 were, frankly, bewildering.

Every day of our lives, women like me were taught to go over a mental checklist of ways to avoid getting raped. The list had become second nature, so deeply, seamlessly internalized that the doorbell only had to ring, and my mother and I, hanging out in our home, watching TV, or maybe making dinner, would first reach for a scarf to throw over our bodies before we answered the door. At my high school, where uniforms were mandatory, girls were asked to kneel on the ground, so the teachers could check if our skirts were long enough. If they didn’t touch the ground, they were too short, and a particularly terrifying teacher would rip open the hem of our skirts, those frayed edges marking us for the rest of the school day. There were a million ways to dress like a slut if you were a girl (there were no such codes for boys) — our white shirts could be “too transparent” if the cotton had worn thin from frequent washing or if we wore colored bras inside instead of white or “skin”-colored ones.

When I was a 25-year-old reporter, I went to ask a group of young girls who lived in a slum in Govandi, Mumbai, what their checklist looked like. What did paranoia look like in a place where thin corrugated sheets of steel were all that stood between the girls and their neighbors, adult men, leering boys?

Fourteen-year-old Nafisa told me she made sure she texted her friend Neelu before she left home. Neelu carried red chili powder with her everywhere she went in case she needed to throw it in the eyes of a potential attacker. Annu made sure her water bottle was always full so that she had something heavy to hit a potential molester with. Pinki had stopped wearing glass bangles once she turned 11 — because her mother told her that if someone grabbed her wrists, they would break and injure her, slowing her down as she ran from her attackers. Neena had stopped wearing her hair down because it attracted too much attention. At 15, most of them avoided going outdoors unless it was absolutely necessary, and when they did, they were usually accompanied by an older male from the family. A lot of the older girls carried small knives in their bags but were unsure if they’d be able to use them when the time came.

Some girls who wore hijabs said they did not feel any safer: “They want to find out what is underneath,” Nafisa said.

If adulthood was the steady accumulation of survival skills — a realization of one’s own power and its limitations — womanhood, for as long as I’d known it, appeared to be about developing a sixth sense that warned you when you were in a specific kind of danger from a man. But the news we read every day, of women abducted, burnt, raped, killed, appeared to be filled with women whose sixth sense had let them down.

Dibyangshu Sarkar / Getty Images

A SlutWalk in Kolkata in 2012.

The comment that sparked the first SlutWalk, leading to gatherings across 200 cities and 40 countries, didn’t even seem particularly surprising to me. A police officer in Toronto had said to a group of students: “I’ve been told I’m not supposed to say this, however, women should avoid dressing like sluts in order not to be victimized.” It was the kind of thing that ministers, judges, police officers, holy men, and celebrities constantly repeated across the world.

But as the protests began to go viral, we dissected the SlutWalks avidly, over Facebook posts and IRL, in quiet, thrilled tones with other women. When Indian women held their own version of the SlutWalk — the Besharmi Morcha, or the March of Shamelessness — we cheered them on. But privately, I wondered if the entire project of reclaiming a pejorative word was counterintuitive. Did we really need to normalize the word “slut,” or the behavior associated with it, when there was so much else at stake — especially in a country where women struggled for basic rights?

And then there was the question of inclusivity, posed in the open letter from black women to SlutWalk organizers: Who can afford to reclaim the word “slut”? Who are the women whose bodies are always already considered sexualized and without agency by the patriarchy, and did the marches have space for sex workers? Trans women? Dalit women? Were the SlutWalks about provocation or about language? Were they only for the rights of privileged white women? Could we ever change the power imbalance that routinely blamed women for inviting sexual assault just by walking down a street?

In 2012, the conversation turned dark and urgent in India, when the gang rape and murder of a young woman in New Delhi sent tens of thousands of women marching on the streets. Overnight, our fear had birthed an inchoate rage — against the culture of shame, against the constant policing of our bodies and clothes and words and movement. We wanted more than just the right to be safe, we wanted the right to roam the streets and hang out in public and take risks and have fun like any man, without fear of assault. We demanded justice; we also demanded joy. And for a moment, it seemed as though something might really change.

The next year, the world changed so much that it became unrecognizable to me. I was sexually assaulted, not by a stranger on a dark street corner, but by a person I had known and trusted for many years. I testified in court against him and felt as though I had set my entire life on fire. I lost my job, moved cities, moved back in with my mother. Scores of people and professional opportunities disappeared from my life. (The accused denies any wrongdoing.)

From the depths of my nightmare, SlutWalk, even with its problems, represented a spectacle of sex-positivity. It felt like a world of color and hope that I would never inhabit again. People from a range of genders and ages were still gathering in Spain, South Africa, India, and Pakistan, marching in the streets wearing school uniforms, office clothes, lace and leather, nuns’ habits, fishnets, and denim — flashing skin, drumming, dancing, holding babies and signs, and sharing stories of rape and assault and trauma and songs and jokes.

Meanwhile, I was called a slut all the time, by people close to the man who abused me, his lawyers, others who had never met me but were convinced I had lied — by strangers on the internet. I became less interested in reclaiming words and dissecting them. I was tired and suicidal, and I wanted to focus on being something more than, other than, separate from what happened to me and my body. The SlutWalks were described as the most successful feminist action of the last two decades. What good was any of it going to do?

It wasn’t until 2017, when women first began to speak publicly and loudly about Harvey Weinstein and the things they said he had done, that the fog of the past few years started to clear: For some of us, the SlutWalks had been our first moment of articulating collective rage.

For women, particularly those who were in our twenties or younger when this decade began, our only point of reference for women’s rage had been photographs from the anti-rape movements of the ’60s and ’70s, or marches called “Take Back the Night” — women occupying city streets at hours when decent women were supposed to be safe at home. Some of us knew about feminist theory, the first wave and the second and the third, still more of us knew that no matter where we were, our rights were precarious. Many of us now had opportunities our grandmothers could only dream of, but we were marching for the same old shit. Our bodies were still our first battlegrounds.

The next billion people — including women — who are learning about the power of collective action on the internet are from places like India, China, South Africa, Brazil, and the Middle East. These women have grown up in worlds where public spaces are fraught with danger and private spaces are frequently regarded with shame. As a teenage girl in Pakistan learns a new language of sexual freedom and identity online, she is also learning to navigate the murky waters of digital abuse that a woman lawmaker in the US is punished for. The cautionary tales of trolling, doxing, being targeted with rape threats, having intimate photographs posted online for all to gawk at, being morphed onto naked bodies on a random porn site all exist. But so do the possibilities of forming solidarities, joining protests beyond geographical confines, allowing more women than ever before to have a voice — and to listen in. The measure of successful feminist action, I learned this decade, has never been only about changing laws, governments, or workplace policies. Anger itself is clarifying, because it changes us, the people who participate in it, by giving us ways of seeing: seeing ourselves as part of a collective, seeing through patterns of abuse, seeing as in witnessing each other’s lives and stories.

In this decade, we have seen women’s rage move front and center — it is the subject of books and films and television shows. Beyoncé feels it, so does Greta Thunberg — a 16-year-old climate activist who only recently was told by the president of the US to seek anger management.

But, in workplaces, in courtrooms, at universities, on red carpets and during election campaigns, women are still expected to articulate that anger in the most bloodless way possible, in order to seem rational, likable, electable, and believable.

Hindustan Times / Getty Images

Students protest in Mumbai on Dec. 3, 2019.

Carefully contained anger has a role to play in history. Over the years, we’ve watched Anita Hill testifying against Clarence Thomas to an all-male, all-white jury that dismissed her account of being harassed at work. We read the letter that Chanel Miller read out to Brock Turner — a man who sexually assaulted her, but served only three months in prison. We witnessed Christine Blasey Ford’s restrained terror when she was forced to face the man who she said sexually assaulted her. We listened to Nadia Murad, as she described with every shred of dignity she could muster the ethnic cleansing, genocide, and rape of Yazidis — and then again, when Yazidi women were made to confront their rapists on the news.

It is telling that the backlash against the #MeToo movement, in the form of defamation and libel and aggressive defense lawyers, has sought to drag women back to the courtroom: a space they did not trust with the trauma of their abuse in the first place, a place where they are treated as though they cannot be credible witnesses to their own truths.

Yet women’s rage is still unruly: It frustrates all attempts to contain it, shocks, confuses, and provokes. And its unruliness is productive. What else can explain the fact that women are still gathering and marching together across the world? That a day after Donald Trump — a man who was recorded on tape bragging about sexually assaulting women — was confirmed as president of the USA, women held the largest protest in American history? This year, women declared a feminist emergency across 250 cities and towns in Spain, after years of gang rape acquittals, domestic violence, and murders, despite being called “psychopathic feminazis.” In Argentina, the murder of teenage girls, abortion rights, and widespread harassment sparked #NiUnaMenos (Not One Less Woman, Not One More Death) — mass strikes in 2015 which spread across Peru, Bolivia, Uruguay, and El Salvador, and most recently Chile, where this year, a street protest has turned into a feminist anthem performed across Istanbul and Latin America. In South Korea, over 40,000 women protested an epidemic of spy cameras in dressing rooms, unleashing the largest women-only strike in the country’s history. And in India, women came together to form a 385-mile-long human wall against hundreds of years of patriarchy that illegally restricts their entry into a Hindu temple.

It’s 2019, and everything is both terrible and fine. If you feel tired, inhale, exhale, drink some water, and take a break. But remember, even this form of self-care is a luxury for 785 million people on this planet who lack access to clean water, and hours spent looking for water locks women across the world in a cycle of poverty and abuse. In China, polluted air is being linked to an increased risk of miscarriages; in India, Pakistan, Sydney, and California, a deep breath can be hazardous.

Meanwhile, that thing we all need more of — time — is marching on, and so must we. ●

Sahred From Source link World News

from WordPress http://bit.ly/2ZbBGzA

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: The Stories of Asian American Activism in 1970s LA

Installation view of publications in Roots: Asian American Movements in Los Angeles 1968–80s at the Chinese American Museum (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic)

LOS ANGELES — “Instead of going to class, I’ve been working with the Asian Student Mobilization Committee,” a college student wrote in a letter to their mother in 1972. “If nothing else, the events of the past week have convinced me … that prolonged struggle and political education are necessary to effect change.” So begins one young person’s politicization, borne out of opposition to the US wars in Southeast Asia and galvanized by the sight of “friends and fellow students getting their faces smashed with night sticks.”

The letter is one snapshot of Asian America contained in the Chinese American Museum’s Roots: Asian American Movements in Los Angeles 1968–80s. Through books, posters, films, and music, the exhibit brings together varied local histories of movement building by Asians and Pacific Islanders, from anti-gentrification protests in Chinatown to Samoan community organizing in the South Bay. It’s a timely look at the shapes and forms of resistance that can inform today’s political struggles against an emboldened front of white supremacy and xenophobia.

Come-Unity newspaper (May 1972), published by the Asian American–led organization Storefront, which created grassroots programs for the mostly black residents in its neighborhood

According to the Los Angeles Human Relations Commission, hate crimes against Asian Americans tripled in the US in 2015 as part of an overall growing rate of violence against people of color; one civil rights organization recently responded by establishing the first tracker of hate crimes against Asian Americans. After Donald Trump’s inauguration, the White House website was changed to remove all references to the White House Initiative on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI), which had previously worked to increase AAPI access to federal programs, and no longer mentions Asian Americans, or any other minority group, as a policy focus. Since Inauguration Day, 16 of 20 members of the President’s Advisory Commission on AAPIs, among them prominent community leaders and public figures, have resigned in protest against the Trump administration’s discriminatory actions.

The hard-won gains of past activists, whether the establishment of ethnic studies departments at universities or social services for immigrant communities, now face threats by exclusionary policies that are nothing new to the US. But what has also not changed is the potential of self-organized communities to wrest power and resources away from oppressive institutions. The stories presented by Roots give a sense of how the early Asian American movement sought to overcome atomization and define itself. Importantly, it was not exclusively preoccupied with the struggles of its own members — solidarity with Latinx, Black, feminist, and third-world movements was a foundational and evolving part of its activism, one that defined liberation as social and economic justice for all, not just some, groups of people.

Installation view, Roots: Asian American Movements in Los Angeles 1968–80s

The Vietnam War was the major crisis that politicized Asian Americans, but events at home also became key battles that forced them to think of foreign and domestic policies as a unified attempt to disenfranchise people of color. Resembling the graphic illustrations of Black Panther artist Emory Douglas, a poster by artist Leland Wong celebrates 1971 as the “year of the people” and depicts armed resistance against police brutality. A 1970 newspaper, echoing today’s gentrification struggles, commemorates the effort to preserve low-income housing for the elderly Chinese and Filipino residents of San Francisco’s International Hotel. Another poster, from 1982, calls for medical aid to survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings, with additional demands for an end to US military interventions abroad as well as racism within the country. These examples emphasize how Asian American activists perceived violence in and outside of the US as connected: calling for an end to one necessitated calling for an end to the other.

Clockwise from left to right: Poster for poet Lawson Inada’s performance in Los Angeles (1971), image of playwright Frank Chin speaking at the University of Southern California (date unknown), and photograph of silkscreening workshop (date unknown)

Art became a significant outlet for writers, musicians, visual artists, and filmmakers seeking to voice their identities and political struggles. The Amerasia Bookstore in Little Tokyo, which operated from 1971 through 1992, served as a hub for movement publications and writers like Lawson Inada, a Japanese American poet who spent part of his childhood in an internment camp during World War II. Inada, playwright Frank Chin, and others would go on to publish Aiiieeeee! (1974), the first major anthology of writing by Asian Americans. In her book Serve the People: Making Asian America in the Long Sixties, which is an indispensable companion to the Roots exhibit, writer and filmmaker Karen Ishizuka says:

The arts of activism intersected the lives of those touched by them, creating meaning, defining purpose, and acting as a catalyst for change. The preponderance of creative expressions alongside critical analyses of U.S. imperialism and manifestos of anti-racist programs attests to the cultural as well as political revolution that gave birth to Asian America.

As continues to be true today, these artists of color created work both in response to political currents and out of personal necessity, telling stories that were otherwise not being told. Los Angeles collective Visual Communications (cheekily abbreviated VC) produced independent films documenting the lives and histories of Asian Americans that served as a counterpoint to the villainous or reductive stereotypes of Hollywood. Some of those films are on display in Roots: the cross-cultural and transpacific sounds of Japanese American jazz band Hiroshima is the subject of VC co-founder Duane Kubo’s “Cruisin’ J-town” (1975), while Linda Mabalot’s groundbreaking “Manong” (1978) portrays the labor struggles of Filipino farm workers in the Central Valley.

vimeo

Also on view are several editions of the newspaper Gidra (1969–74), which served as the major communications arm of the Asian American movement. Founded by UCLA students and run entirely by volunteers, the publication produced political analyses, satirical cartoons, and other coverage of everything from the Vietnam War to global capital to cultural stereotypes. Visually rich and politically incisive, the newspaper’s articles and illustrations suggest a patchwork of perspectives and identities that comprised 1970s Asian America.

A section of the exhibit titled “Feminism and LGBTQ Movements” features the January 1971 edition of Gidra, whose cover announces it as a “special women’s issue.” The need for a special issue suggests that women’s voices had not been centered or recognized to the degree they should have been. Two photographs depict Gidra volunteers — all female — in the midst of one of several “wrap sessions” that led to the creation of the women’s issue. Despite the radical claims of the movement, Asian American artists and activists had plenty of blind spots, as the exhibit takes pains to demonstrate. Many of the leading members skewed male, cisgender, and heterosexual, with identity politics based on an opposition to “feminized” or “emasculated” personas (the editors of Aiiieeeee!, for example, defined “feminine” writers as not being “truly” Asian American). Facing these limitations, feminist and queer activists organized to create their own support systems and platforms that centered labor, health, and other issues that did not always find a home in the larger movement.

Newsletters published by the Asian Women’s Center

In a part of the exhibition, visitors are invited to write on Post-it notes in response to a series of guiding questions, one of which asks, “What does Asian American mean today?” Implying that present Asian American discourse is at odds with its radical past, one note lists “silence,” “anti-blackness,” and “white assimilation,” while another names “complacency” and “ignorance.” These seem to be responses to the historical amnesia and political atomization that have led to Asian Americans demonstrating on behalf of someone like Peter Liang, the Chinese American cop who murdered an unarmed black man, Akai Gurley, in 2014. That was a far cry from 1975, when thousands of Asian Americans packed the streets of New York’s Chinatown to protest for Peter Yew, a young engineer who was brutally beaten by police, and against all forms of oppression and discrimination. “Asian American” was once a radical marker of identity, yet today it can feel like a rather innocuous or less meaningful designation. It can even seem conservative or reactionary.

Growing up in Southern California during the ’90s, I recall the fear and anxiety of the local Korean community during the LA uprising, when many Korean-owned businesses at the epicenter went up in flames. I was too young to grasp the root causes of the riots, but old enough to understand that the video of the four cops beating Rodney King (which was played ad nauseam on television) had something to do with them. What I didn’t know at the time was the name of Latasha Harlins, the African American teenager murdered, just a year before the uprising, by a Korean shop owner who suspected her of stealing a bottle of orange juice. Some Korean Americans recall how the community came together to defend itself and rebuild what was lost, but I have to wonder exactly whom they were defending against and who was being left out in the first place.

Although social movements like the early Asian American one do eventually reach their terminus, the story of Asian America — as vast and nebulous as it has always been — doesn’t end with the 1980s. The objects in the exhibit comprise a vibrant history of uprisings, provocations, and world building, but how do we avoid relegating resistance to the past? Today, although they may not always be visible to the mainstream, many young Asian Americans have taken up the mantle of political struggle, continuing where earlier movements left off and expanding the fight to include intersectional identities and solidarity. Whether it’s queer diasporic Koreans showing up for Black Lives Matter or anti-imperialist Filipino activists marching against the Israeli occupation of Palestine, Los Angeles remains home to many Asian American activists of multiple generations. Roots will hopefully not be the only attempt to present stories of political activism and movement building by Asian Americans, whose work seems more urgent and vital than ever.

Installation view, Roots: Asian American Movements in Los Angeles 1968–80s

Gidra (February 1973)

Installation view of ephemera from Filipino American activist movements

Alan Takemoto, poster marking the 10th anniversary of the annual pilgrimage to Manzanar (1979)

Installation view, Roots: Asian American Movements in Los Angeles 1968-80s

Roots: Asian American Movements in Los Angeles 1968–80s continues at the Chinese American Museum (425 North Los Angeles Street, Los Angeles) through June 11.

The post The Stories of Asian American Activism in 1970s LA appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2mPRmU5

via IFTTT

0 notes