#that’s the only place I can think of atm that retained the status

Text

Hmm… Cornish Western story… hm

#OKAY BUT THIS HAS SOME HISTORICAL VALIDATION#bc okay. in the 1830s there was this MASSIVE Cornish emigration#Cornish tin and copper was drying up and the mining business overall in the uk was coming to its heat death#so boom. no more work for a VAST MAJORITY of Cornish folk#so a lot went to South and Cebtral America and a lot went into the US west and Midwest#because westward expansion was also happening (fuck) and so hey#there’s more work out west and in the Americas#just grass valley Cal. was 3/4 Cornish by descent by 1911#so there was a huge Cornish diaspora group in the American west#there were tons of places labelled as “’little Cornwalls’ all throughout the west#and in mexico too!! real de monte!#that’s the only place I can think of atm that retained the status#now clearly there’s way more nuance to it and a far more complex history#especially when talking abt Manifest Destiny and the suchlike#ik that Cornish miners were being PAID to leave Cornwall for Australia to work but I can’t find anything about anything like that happening#re: immigration to america. it’s an incredibly fascinating history bc it did help out the Cornish economy in ways#still quite a few men went over and sent money back to their families#but anyways. to bastardise an entire period in history#cornish western#(multigenerational story? classic revenge ie escaping a past?)#I should be banned from thinking I don’t do anything good with this ability#its actually an idea I’ve had for a while but only in vague shapes#I just think Cornwall is pretty and I’m deep in its history. I also think the American west is pretty and I’m fascinated by ITS history#kicking a tin can around in my brain with my hands in my pockets#anyways

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

My voice in the background story: my PhD thesis preamble

[This section is the opening on my submitted PhD thesis, under examination atm]

I am a woman and mother from the south, born and raised in the state of Chiapas, Mexico. Since childhood, my family and I have often visited San Cristóbal de las Casas, a picturesque city surrounded by hills, that maintains its Spanish colonial layout and architecture, with red tile rooves, cobblestone streets, and wrought iron balconies, often strewn with flowers. This city is still considered the culture capital of the state due to its history and Indigenous population.

Visiting the mercado (market) of Santo Domingo was an important part of our weekend trips. This outdoor market remains a colourful display of Indigenous crafts surrounding the beautiful eponymous church, and its side chapel Templo de la Caridad. The stalls are filled with creative and ancestral traditions such as textiles, embroidery, saddlery, basketry, jewellery, and stones. Over the years, I became consciously aware of how the motifs, colours and styling of the displayed garments were evolving. I also started to notice the emergence of crafts from other Latin American countries, now contrasting with mass-produced pieces from Mexico, Latin America and Asia. I started my studies as an industrial designer, and these changes became increasingly evident, further piquing my interest in the development, quality, making and meaning of crafts. It turned into an obsession. I regret not keeping all of the garments acquired since I was a child, or at least not taking pictures of them to retain a visual record of the evolution.

After graduating and working for a couple of years, I moved to Spain to do a master’s degree in design management and product development. In the coloniser’s land, I questioned many things about identity, race, ethnicity, gender roles, social inequalities, migration, and colonisation, amongst others; it was a face-to-face encounter with my “otherness”. Until that point, I had been a middle-class Mexican mestiza woman. Living in Europe made me discover that I was a Latina, a “Sudaca” (pejorative term for South Americans), and a migrant, and I had to unlearn the conditioned “pursuit of civility” and make a firm decision to root myself better in my own land and culture.

Back in Mexico, I got my first job in design education, married, and continued to “follow the script” for a woman of my age and socio-economic status. But I dreamt of collaborating with Indigenous communities to “help them improve” their work in things like quality, standardisation, and the creation of new products that were more suitable to a contemporary lifestyle. I was certain design could impact their crafts and communities in a positive way, and because of this, I wanted to co-ordinate designer-artisan collaborations around the world. This led me to apply for a Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) scholarship for the training programme in Modern Design and Traditional Craftsmanship in Japan, which I was fortunate to obtain. In 2009, I spent nine months under the tutorship of Yamamoto sensei from the Kyoto Institute of Technology, and was awed by the beauty of making Japanese crafts under such distinguished masters. The result of this programme was the creation of a design guide for artisans in Mexico in collaboration with my two fellow design kenshuin (trainee). We blended the Japanese learnings, observations, design, creativity, and ways of making crafts, with traditional Mexican games, to make the design process enjoyable, familiar and non-invasive.

Life continued on my return to Mexico, and my daughter was born in 2011. The same year, we moved to Singapore (where I could not legally work), for my former husband’s job, away from family and friends. I learned to be a mother, and an “ex-pat” wife, largely in isolation. There were multiple challenges in this new land, but travelling around South East Asia kept me afloat. In my disconnection from home, exploring culture and crafts became my focus and saviour. The contrast between Singapore’s affluence and the neighbouring “underdeveloped” countries further ignited my sense of social justice and fuelled a desire to walk alongside those communities. After three years in Singapore, fortunately, an opportunity to go to New Zealand emerged, and we moved again.

The many journeys through various countries, cultures, and identities, shifted my views of crafts, which, despite my conventional design training, I now considered as art. I was more interested in the artisanal communities, and their understandings and ways of embracing heterogeneity, rather than standardisation and universalisation, and the exploration of links between art-design-crafts to nature-culture, as well as the importance of creative-art practices to individual and collective well-being.

Life’s challenges continued.

In July 2015, I started a part-time lecturing position in the School of Art and Design at Auckland University of Technology, and in March 2016, I was accepted into a PhD programme. It was also the month my marriage ended. The support of Dr Amanda Bill, my manager and supervisor support, at that time was crucial. After a few months, I took leave from my PhD while I taught more hours to support myself and my daughter, and applied for a Vice-Chancellor’s scholarship, of which I was an incredibly blessed recipient. I restarted the research journey in January 2017. During my PhD years, institutional and life changes impacted my research, resulting in a change of faculty from Design and Creative Technologies to Te Ara Poutama – my current whare (house) - where I was warmly welcomed. I have had five official supervisors and one non-official one, due to my change of faculty. I have learned from the words and actions of all of them.

I have been fortunate to attend many Māori and Indigenous research and design events in Aotearoa-New Zealand, Australia, and Canada, sharing with other “mixed” Indigenous people like myself. From them I learned that mixed ancestry does not erase our Indigenous heritage, and one identity is not exclusive to the other, but rather, they co-exist.

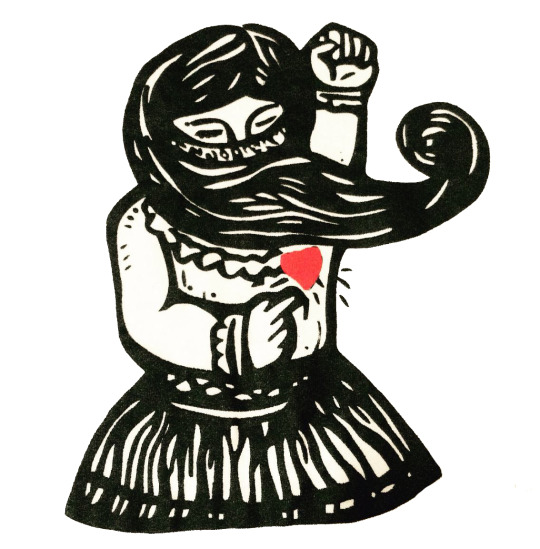

Parallel to the PhD life, and ignited by life’s struggles as an “ethnic migrant solo mother”, I started to volunteer in community projects, particularly in the Latin American community. I was invited to be a board member for a non-for-profit organisation working with refugees and migrants using design and co-design; I participated in forums and conducting workshops; I returned to creative and activist practice through textiles; I co-founded the Buen Vivir women’s collective and joined the Sororidad Latina group, involving my daughter in everything. Using art and textiles, I joined public demonstrations against racism after the March 15th terrorist attack in Christchurch. I fought gender and diversity inequality in design, climate change, and denounced femicide in Latin America to mention only a few.

While the past four years have been transformational professionally and personally, I understand these are but a series of short cycles in a life-long journey. In some ways, I consider this PhD to be the formal approach to a topic that has always been an incredibly pivotal component of my heritage, and central to my life: namely, culture through art-design-crafts, particularly textiles. I am fortunate and grateful that this part of my identity can form the basis of PhD research. I have learned much about this from mis compañeras of Malacate Taller Experimental Textil (independent textile collective and research partners), Mayan artists and scholars, and their embodied experiences of knowing, doing and connecting. Bonding with these wise women who live/practise their ancestral knowledge has been a true privilege. Nevertheless, the lived experiences of being Indigenous and the onto-epistemic guidance from tangata whenua (people of the land) in Aotearoa, from my supervisor, and research and design whānau (family/community), all contributed significantly to this research.

Throughout these years, I have learned much about myself, to understand my processes as a primarily sentipensante being, and to accept, respect, balance, embrace, and use it positively. I could understand I am someone who feels first, strongly and deeply, needing to let the emotions emerge. However, dealing with people, balancing the emotions of the heart with the reasoning of the mind, to question, understand, and process my feelings, is paramount. I learned I must comprehend other peoples’ emotions, listen to their stories, make sense of their backgrounds, and establish connections from a place of empathy, from the heart. Most importantly, I learned that after the processes of feeling and thinking, the final decision needs to make sense, to have meaning, and for this, it needs to come from the heart. For me, being corazón is not the romantic view of love where everything is positive. Yollotl (corazón in Náhuatl, one of my ancestors’ languages) is emotions; anger, sadness, happiness, fear, to mention some, but it is also the source of courage, passion and peace.

Many transformations have happened in Aotearoa, Latin America and around the world, that have shifted old ways of knowing and doing, towards new possibilities. The Latin American movements in Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, Chile, Haití, Argentina, and México, have inspired and triggered me to participate and contribute whenever and however I can.

At this point, I say I am a mother, a feminist, an activist, a researcher from the south (re)connecting with indigeneity. I am sentipensante, I am Yollotl, I am uno con el todo (one with the whole). This is my truth.

This work is dedicated to my sisters, brothers and third spirits in Cemanáhuac (the Americas), to weavers and anyone familiar with the language of the threads; to women, to mothers (especially solo mothers), to my feminist sisters, a mis hermanas de AbyaYala, a mis sororas…

Con todo, si no, ¿pa´qué? (Give it everything, otherwise, what’s the point?)

(Feminist chant)

#PhD#phd thesis#phd life#phd research#Buen Vivir#feminist#south#nativelatinamerican#latin america#abya yala#indigenous#indigenous studies#decolonisation#decolonial#decolonize#design#decolonisingdesign#woman#mother#native#latina#sororidad#sorority#sentipensante#corazón#corazonar#heart#yollotl#epistemologiesofthesouth#mexico

1 note

·

View note