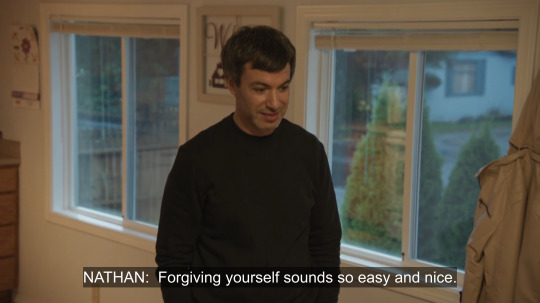

#the rehearsal is like if finding frances was a whole show

Photo

#nathan fielder#the rehearsal is like if finding frances was a whole show#i feel liek tone wise it's similar#j

247 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐞𝐞 𝐚𝐦’𝐬 ♱ 𝐣𝐢𝐦 𝐫𝐨𝐨𝐭

waking jim up at shit in the morning for sexy time hehehe

words; 1268

smut!

-

“Jim?” You whispered. He snored in return, dead asleep.

Jim’s eyes were closed as his chin rested on your head. His arms were tightly wrapped around you, his bare upper body pressed against yours.

The hotel room was completely black. It was three in the morning, and you had joined Jim on tour.

Your body, along with your mind, had entered a restless and frustrated cycle. You weren't used to all of the travelling, and you'd found it hard to fall asleep at night.

You were in France, in a beautiful hotel. Jim slept like a rock but you just couldn't find any rest.

And you’d tried everything. You’d tried cuddling Jim, and then you'd tried sleeping alone. You’d tried sleeping without covers and then with them. You’d even tried popping a melatonin, but then you had to pee, and suddenly you were back at square one.

You just had this burning feeling, something you needed to get done to rest.

Your cheeks blushed red at the thought, your stomach tingling even more.

You needed Jim, and you had no idea as to what had incited this sudden need to be fucked by your boyfriend, but it was undeniable.

You shuttered at the thought, imagining how Jim would make you scream, and fuck the daylights out of you. You wanted that. So bad.

A wet spot had formed in your panties. You bit your lip, a tingling feeling washing over your whole body.

“Jim?” You whispered again, this time looking up, grazing his face softly.

He hummed in response, giving you a little squeeze, still asleep.

You snuck your hand under the covers, grabbing Jim’s thigh and raising it to curve perfectly between your legs. His knee was pressed against your cunt. He could surely feel the wetness between your legs on his knee by now.

You moaned and grabbed Jim’s hair.

“Y/N, no,” he mumbled and lowered his leg, removing it from your soaking cunt.

You cried at his shifting, squirming a bit.

“Jim,” you pleaded, wrapping your arms under his, clutching him tightly, and placing kisses on his collarbone.

“I can't sleep, Jim,” you lamented. Jim sighed tiredly and kissed your forehead, eyes still closed, barely awake.

“Try,” he encouraged and puffed. “I've tried for the last three hours. I can't sleep,” you moaned.

Again, Jim just hummed in response, so tired that he couldn't think of much else to say.

You felt a bit bad since you weren't the one playing ninety-minute shows every night, doing interviews and rehearsals. It made sense that Jim was exhausted, but you had other things to worry about.

Your hand left Jim’s back and went down under the covers. You placed your cold hand on his thigh, brushing it slightly. The coldness of your hand caused Jim to flinch slightly.

You were so insistent, and your need for Jim only grew bigger. You just had to get him in the same mood as well, but it seemed impossible.

You let your hand travel further up Jim’s thigh until you reached the leghole in his boxer shorts. You bit your lip as you watched Jim’s face intensely, hoping for a moan or a smirk, but you got the opposite.

“I'm so tired, Y/N. Not now,” he grumbled and reached down to remove your hand from his thigh, placing it on his chest instead.

“I’ll never ask again, James, I promise,” you pleaded in a whispering voice. You felt nauseous, that's how sexually frustrated you were.

Just the idea of Jim pounding you, made your eyes roll to the back of your head.

“Please, just do something,” you cried softly and kissed Jim’s lips.

Jim, to your surprise, turned around, back facing you and continued to sleep.

Your bottom lip folded and you huffed, sighing as you stared into the ceiling, fully awake, mind focused on one thing, and one thing only.

Jim reached his hand over for you to hold. He hated not having physical contact with you when sleeping. You grabbed his hand and placed it on your thigh.

You'd run out of ideas completely. Now, you only had one last dirty trick left.

As his hand rested on your thigh, you pulled down your panties, making sure that Jim felt what you were doing. You were completely naked.

As Jim’s hand rested on your thigh, you moved it up so far, that his pinky was resting on top of your cunt.

Then, the dirty trick. Your hand travelled down to your soaking cunt, running your fingers up and down your slit a few times, hand brushing against Jim’s as you began rubbing your clit, moaning a little louder than you normally would.

“F-Fuck, J-Jim,” you moaned, imagining his hand instead of yours. With your other hand, you held onto Jim’s forearm, squeezing it hard as pleasure rolled over you.

You brought his arm up and placed his hand on you breast.

Finally, he turned around.

“You're so goddamn stubborn,” he hissed and smacked your hand away from your cunt, replacing it with his.

He began rubbing your clit in a circular motion, kissing your neck while doing so. At the same time, you reached down, digging your hand into Jim’s boxers, straddling his cock, feeling as it stiffened up in your grasp within a heartbeat.

He moaned softly as you pumped his cock, making you produce equally loud moans as he pumped his long fingers in and out of you.

You felt it was reasonable if you took care of him for a bit. After all, it was you who woke him up just to fuck.

You rolled over, placing your legs on either side of Jim’s waist. You rode his cock for a while, grinding him before eventually pulling down his boxers, his hard cock springing out.

You grabbed a hold of Jim’s hands and placed them both on each tit.

He squeezed them firmly as you sank down on his cock.

A series of cuss words mixed with your name left Jim’s mouth repeatedly as you began bouncing up and down at a steady pace, head thrown back in pleasure, hoarse moans leaving your quivering lip.

He was deep inside of you, and if the light was turned on, you would've gasped at the sight of the bulge his cock created in your stomach.

Your knees were getting tired, and Jim could tell.

He lifted you off him and stood on his knees just as you. He grabbed your shoulders and forced you down on all fours.

He gathered your hair in his fist and drove into you without a warning. You helped at the feeling of him stretching your walls completely. You were in pure bliss.

Jim squeezed your ass tightly as his hips smacked against your ass cheeks, creating a loud sound that echoed through the room.

Your face was buried into the pillow, which you bit into for dear life, trying to prevent yourself from screaming at the top of your lungs.

Jim continued his nearly painful pace, thrusting so fast that you could barely think. And the position allowed for extra depth, doubting if that was even possible.

“I’m gonna c-”

Jim grabbed both your hands and pressed them against your bag as he continued to thrust.

“Come for me, baby.”

You did exactly that, reaching your climax, nearly seeing stars as you tried to collect yourself, although Jim was still going at it. “God,” you cried and breathed heavily, not sure if your body could handle much more.

Jim came with one final deep thrust. He pulled out and threw himself down beside you, sweaty and all.

“Thanks for waking me. I think I needed that.”

#chris fehn#corey taylor#craig jones#james root#jim root#jim root x reader#joey jordison imagines#slipknot x reader#slipknotimagines#slipknot photos#slipknot#slipknot fanfic#stone sour#slipknot smut#jim root x female reader#joey jordison x reader#james root imagine#jim root imagines#jim root imagine#sid wilson#shawn crahan#paul gray#heavy metal imagines#metal imagines#murderdolls#metal#heavy metal#smut

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

After the cut, the Rolling Stone article that elicited a response from Roger, written on an airline motion-sickness bag.

Queen Holds Court in South America: On the road with rock's royal spectacle (x)

James Henke, June 11, 1981. Buenos Aires, Argentina

We are the champions – my friends

And we’ll keep on fighting – till the end –

We are the champions –

We are the champions,

No time for losers cause we are the champions – of the world –

—Freddie Mercury, “We Are the Champions”*

It was to be the Big Event. Queen, coming off its most successful year ever, was setting out to conquer South America and wanted to make sure the whole world knew about it.

That, certainly, was no surprise. After all, this was the band that had made a career out of creating spectacles. A couple of years ago, for example, when they were launching a U.S. tour in support of their Jazz album, Queen threw a bash in New Orleans that featured snake charmers, strippers, transvestites and a naked fat lady who smoked cigarettes in her crotch.

The real surprise was that Queen – a group with a history of hostility toward the press – had agreed to do interviews and had invited journalists from the U.S., England, Spain, France and other countries to come along for the first shows.

So here I am at Ezeiza airport, outside Buenos Aires. The place looks like a military installation. Young, peach-fuzz-faced boys who can’t be more than sixteen or seventeen are stationed along the concourse that leads through customs into the baggage-claim area. They’re all in uniform: big black leather shit-kicking boots that reach halfway up the calves of their legs, and regulation tan pants, shirts and helmets. And they’re all armed with submachine guns.

In Argentina, the military – and terror – reigns supreme. According to Amnesty International, about 15,000 people have “disappeared” since 1976, when Juan Perón’s second wife and successor, Isabel, was thrown from power in a coup d’état. Since then, a guerrilla war has been waging between the dictatorship and opposition groups, mainly Perónists, and citizens have routinely been plucked off the streets or out of their homes, taken to secret detention camps and systematically brutalized. But as VS. Naipaul writes in his book The Return of Eva Perón, “Style is important in Argentina; and in the long-running guerrilla war – in spite of the real blood, the real torture – there has always been an element of machismo and public theatre.”

Editor’s picks

Amid the hubbub at customs, I notice a middle-aged man in gray – gray suit, gray tie, gray hair – making his way through the crowd, shouting something in Spanish. The only word I understand is Queen, and sure enough, he’s looking for us. He takes our passports, whisks us past the inspectors without so much as one bag being opened, and leads us upstairs to the bar for an early morning cerveza. He speaks little English, but there are two words he knows quite well. No matter what anyone asks for, his response is the same: “No problem.”

Maybe this won’t be so bad after all.

By the afternoon of day two, none of the writers has yet been introduced to any of the band members. We while away the time in the hotel bar, but in this country, where the annual inflation rate is around 100 percent, a bottle of beer costs the equivalent of twelve dollars, keeping us sober against our wills. Finally, Jim Beach, Queen’s business adviser, allows a few of us to attend the sound check at Velez Sarfield.

The Argentines have a rather nifty concept of crowd control, as I find out when I reach the stadium: a moat, about six feet wide and three feet deep, runs around the perimeter of the field and is filled with foul-smelling water and patrolled by dragonflies. Queen has brought its own artificial turf so that the promoters will allow people onto the field.

Up onstage, Queen – lead singer Freddie Mercury, guitarist Brian May, bassist John Deacon and drummer Roger Taylor – is rehearsing “Rock It (Prime Jive),” a track off The Game. And it sounds simply awful. The acoustics are horrendous in the 3500-seat stadium: there’s a thirty-second delay as the music drifts across the length of the field and reverberates off the scoreboard. Nor does the band’s musicianship seem inspired. The rhythm section is sloppy and sluggish; May’s guitar playing is limited to heavy-metal/hard-rock clichés and patented, though by now boring, harmonic lead breaks; Mercury’s singing is lackadaisical and without conviction.

Related

“They’re not even up to the par of some third-rate New Jersey bar band,” another writer comments to me, and indeed, I’m somewhat mystified about what it is that makes this group so popular.

When I return to Velez Sarfield that evening for the show, the stadium is swarming with kids – and cops. These are crusty, corpulent tough guys – not the boot-camp boys I saw at the airport. And it doesn’t take long to find out that they mean business. When one American writer snaps a photo of the twenty-odd billy-club-wielding policemen who are cordoning off the backstage area, he’s pinned against a government-owned Falcon and threatened at knife point with the loss of a finger until he yields his film. “No problem.” Sure.

“Un supergrupo numero uno,” the emcee anounces as the lights dim, and with a burst of smoke, Queen appears onstage and begins hammering out its anthem, “We Will Rock You.” Mercury – dressed in a white, sleeveless Superman T-shirt, red vinyl pants and a black vinyl jacket – frequently stops singing and dares the audience to carry the weight. And carry the weight they do: the fans seem to know all the lyrics throughout the 110-minute show – which, if for no. other reason, is impressive for the number of hits the group is able to offer up, such as “Keep Yourself Alive,” “Killer Queen,” “Bohemian Rhapsody,” “Fat Bottomed Girls” and “Bicycle Race.”

Though the band-audience interaction is remarkable, the crowd responds with such unquestioning devotion I get the feeling that if Freddie Mercury told them to shave their heads, they’d do it.

The musicianship still seems pedestrian, but what the group lacks in ability, it makes up for – at least to the fans’ satisfaction – in gimmickry. Smoke shrouds the stage at regular intervals; flash pots illuminate the audience at key moments and end the set. Compared to Kiss‘ fire-breathing antics, Queen’s use of special effects is in relative good taste, and after all, a Queen show is supposed to be a spectacle.

For the encore, the band reprises “We Will Rock You,” then bounds into “We Are the Champions.” Mercury, by this time wearing only a pair of black leather short shorts and a matching leather policeman’s hat, struts around the stage like some hybrid of Robert Plant and Peter Allen, climactically kicking over a speaker cabinet and bashing it with his microphone stand. Pretty ridiculous in this day and age, but the kids love it.

Indeed, Queen may be the first truly fascist rock band. The whole thing makes me wonder why anyone would indulge these creeps and their polluting ideas.

—Dave Marsh in Rolling Stone

What do I think about critics? I think they’re a bunch of shits.

—Freddie Mercury

Queen’s relationship with the music press has been about as cordial as the secret police’s relationship with the Argentine public. Even so, the band hasn’t exactly suffered from the continual pans of its records and shows: eight of its ten LPs have been certified gold (the exceptions are the Flash Gordon soundtrack and Queen II), and its last three studio efforts – News of the World, Jazz and The Game – have gone well over the million mark in sales.

“I have some very strong views of some of the things the press do, such as The Rolling Stone Record Guide,” Roger Taylor says, looking out his hotel-room window. It’s day four, and the long-promised interviews have finally been arranged. “Now, I’ve never read the book, but I saw an ad, and I thought, ‘What the fuck is someone doing bringing out a book like this? Who the hell are they to say what albums are good and what albums are bad?’ I think it’s entirely a personal choice.” (For the record, Queen didn’t fare too well in the book; four of the seven albums reviewed were awarded two stars, a designation that means “records that are artistically insubstantial, though not truly wretched.”)

The shots at Queen have not been fired by just the press, however. When the punks came to fame in England in the late Seventies, Queen was one of the groups most often singled out for attack. Taylor and John Deacon, the two band members who seem most attentive to musical trends, apparently feel some of the criticism was justified. “It gave us a kick up the ass,” Taylor says. “It was so angry, so different, so outrageous. We were recording News of the World in the same studio the Sex Pistols were recording their first album in. I mean, the first time I ever saw John Rotten, I was really shocked, cause I had never actually seen the whole thing in person. He sort of crystallized the whole punk attitude, and there’s no doubt about it, the guy had amazing charisma.”

If the band’s pomp-and-circumstance delivery has recently fallen into disfavor among the rough-and-ready New Wavers, it wasn’t really in vogue either when Queen inaugurated its grandiose stage presentation in the early Seventies. “That was the time of the supergroups, like Cream and Traffic,” Brian May explains, “and it was more the thing to get into your music and not worry about the audience. Then, for a period, it became very cool to do a show. Now, the wheel has turned again. But we just think that kind of show is part of being professional. People are giving you two hours of their time, so you have to give them everything for those two hours. We want every person to go away feeling he got his money’s worth, and we use every possible device to achieve that.”

From the beginning, Queen wanted to put on a show that would be different. “We had a joke that we wanted to be the biggest,” Taylor says. “It was a joke, but underneath, it really was true. Number one is much better than number two. And we’re still working at it.”

To accomplish this goal, Queen opted for an unusual route. Rather than work their butts off playing the club circuit – something Taylor and May had done without much success in a band called Smile – they chose to spend two years rehearsing while they were still in school. May nearly completed a Ph.D. in astronomy; Taylor has a degree in biology; Deacon, one in electronics; and Mercury, a diploma in illustration and design.

Mercury and Taylor supported the band by selling artwork at a stall in Kensington Market, and it wasn’t until 1973 that Queen released its first album and had enough money – thanks to record-company support – to take the kind of show they wanted to do on the road. The LP, titled Queen, gave the band its first hit single, “Keep Yourself Alive,” and set the stage for what was to come. As Roger Taylor says, “It’s been quite a fairy tale.”

I just hate this,” Freddie Mercury says, “especially when that thing’s on.” He points to my tape recorder, sits down across from me and lights up a Salem. “There came a point where I was misquoted all the time,” he continues, “and they had the piece written before they even started. I’m not afraid of criticism – I don’t want to come across as Goody Two Shoes all the time – but it’s been purely vindictive.” A deal’s a deal, however, and Mercury, obviously under some pressure from the other band members and their record company, had agreed to an interview. “So here I am with Rolling Stone,” he moans. “It’s like being forced to talk.”

Up close, Mercury is more petite than he looks onstage: he stands only a fraction of an inch under five feet ten and is relatively slender. His short-cropped hair and mustache are jet black, and his eyes are a piercing dark brown. In addition to being the group’s lead singer and one of its main songwriters, Mercury is also most responsible for Queen’s image. He’s known for his flamboyance and debauchery both onstage and off: at a birthday party a couple of years ago, for example, he swung naked from a chandelier, and on one of the band’s Japanese tours, bored with the tedium of playing night after night, he appeared onstage with a bunch of bananas atop his head.

“The Carmen Miranda of rock & roll,” he says, chuckling. “But what can I say? I’m a flamboyant personality. I like going out and having a good time. I’m just being me. The media pick up on certain things, and a lot of things get overexaggerated. I’m quite easy to get on with, really. I can be a real bitch at times, but that’s okay. I’m not that vicious. I use my influence. Why not? I’m not afraid to flaunt it.”

Thirty-four years old, Mercury was born Frederick Bulsara in what was then Zanzibar. His father was a British civil servant, and Freddie left home when he was seven to attend boarding school, first in India, then in England. “You learn to fend for yourself at an early age. I was quite rebellious, and my parents hated it. I grew out of living at home at an early age. But I just wanted the best. I wanted to be my own boss.”

Shifting around in his seat, Mercury tugs at his upper lip and reaches for his pack of Salems. “For a nonsmoker,” he jokes, “I smoke far too much.” He tells me he’s just purchased a house in London’s Kensington Park, complete with eight bedrooms and a massive studio with pillars and a gallery. “I can have minstrels play there,” he says with a laugh. “Very la-di-da, don’t you think?”

He’s having the mansion remodeled, which gave him cause recently to go on one of his celebrated shopping sprees. Just before their South American jaunt, Queen played five shows at the Budokan in Tokyo, and the promoter’s wife, a good friend of Freddie’s, arranged an excursion for the singer and his entourage through the largest department store. “I felt like Grace Kelly,” he recalls. “I got this huge Japanese bed, a lot of lacquer things and really nice hundred-year-old stuff. I think I spent a fortune, but I don’t know. The credit card pays for it.

“I like buying things on crazy impulses,” he continues. “I hate buying for investment. But I do like a lot of Oriental stuff; it’s intricate and delicate. I also like the cultural part of it, the way they do their gardens; they put a lot of thought into it. But I’m not into all the meditation crap, or those boring tea ceremonies. The raw fish, as well.”

Early on in his career, Mercury seemed bent on incorporating his interest in different cultures and art forms into Queen’s stage shows and music. “Mustapha,” off the Jazz album, was a miserable attempt at Arabic music, and at one point, Mercury told the British press he was “bringing ballet to the masses.”

“I went through this period where I thought I was making an impact on the fashion world,” he says, “then I thought, ‘Oh, grow up.’ And now, you see, I don’t take all this too seriously – I mean, I couldn’t be serious with the things I wear onstage. I have far more fun, and I enjoy it. It’s a great release. That’s what entertainment should be.”

He feels likewise about the band’s music. “It’s just pure escapism. It’s like going to see a film. People should just escape for a while, then they can go back to their problems. That’s the way all songs should be: you listen to them, then discard them like a used tampon. I don’t have any messages I’m trying to get across or anything.”

The forty-five minutes of interview time I’ve been allocated are rapidly drawing to a close, and publicist Howard Bloom knocks on the hotel-room door and tells us to wind things up. Mercury lights one last Salem. “You see,” he says, “you can tell I’m not very good at this. To be honest, I really don’t think I have much to say.”

A couple of years ago, Roger Taylor was doing about 145 miles an hour in his Ferrari on an alpine road in Germany when suddenly one of the chains went, the cooling system died and the car caught on fire. He managed to extinguish the flames just in time – there were about fifteen gallons of gas onboard. “Burned all my clothes to a cinder,” he recalls. “Another minute and it would have hit the tank and that would have been it. I would have been vaporized completely.”

Since then, Taylor hasn’t been quite as enamored of fast cars, but he still relishes the kind of lifestyle rock & roll has afforded him. In that sense, he’s probably closer in personality to Freddie Mercury than the other two band members. “Ah, yes,” he says when I bring up Queen’s rather decadent image. “I like that sort of thing. I like strip clubs and strippers and wild parties with naked women. Sounds wonderful. I’d love to own a whorehouse. Really, seriously. What a wonderful way to make a living.”

“Roger is very much in the tradition of the successful rock & roll musician,” John Deacon explains. “He wants the things that go with it, and it is what he really wanted to be. I’m sort of the opposite of that. It was never my burning ambition to be in a successful band. It has helped my confidence a bit, but it’s different things for different people. And we are four very different people.”

Offstage, while Taylor and Mercury are out carousing, Deacon frequently spends time with his wife and three kids. Though he may seem out of place in the flashy world of Queen, Deacon is actually the band’s stabilizing presence. He oversees much of the group’s business matters – Queen does not have an official manager; instead, it employs a coterie of advisers who leave final decisions to the band.

The disco hit “Another One Bites the Dust” is Deacon’s creation. “I’m the only one in the group, really, who likes American black music,” he tells me. “And with The Game, it was Freddie’s idea that instead of arguing over which songs to put on the album, we’d split it up: Freddie and Brian would have three tracks apiece, and Roger and myself would have two. But we had arguments over whether “Bites the Dust” should be a single. In the end, it began attracting a lot of attention on black stations and in discos, so the record company wanted us to put it out. But it would never have been chosen as a single by the group as a whole.”

Given his low-key personality, I wonder how Deacon feels about the image conveyed by Mercury. His answer is blunt: “Some of us hate it,” he says. “But that’s him and you can’t stop it. Like he did an interview in one of the English national papers, and it was all like, ‘We’re dripping with money, darlin‘,’ or, ‘What’s a mortgage?‘ Brian, for one, just hated it.”

Like Deacon, Brian May is quiet and tends to keep to himself. He, too, has brought his wife and child along. When not touring, he’s an avid gardener – “I’ve been known to be out there looking for slugs at one o’clock in the morning,” he says – and he tries to keep up with astronomy by reading journals and talking with his former university colleagues.

“I think it’s essential that you have things that you get into apart from music,” he says. “You have to maintain your balance.”

May seems to care the most about the group’s audience, and he supervises the fan club. “I think people can listen to some of our stuff and actually get something out of it spiritually, if I may be so bold,” he says. “I enjoy the fact that a lot of people have written to us and said that a particular song helped them when they were in a difficult situation. That’s a great feeling.”

All in all, the Big Event was a success. The attendance was staggering: in Sao Paulo, Brazil, the group played in front of 131,000 people one night and 120,000 the next. The press had also been good: one American writer even mentioned Queen’s shows at Velez Sarfield in the same breath as the Beatles’ at Shea Stadium.

Though this tour seemed rather tame compared with previous Queen endeavors, that probably says more about South American governments than it does about the band. When the group’s advance men first arrived in Buenos Aires, for instance, their backstage passes were seized briefly by customs officials, who deemed them pornographic (they depicted two nude women embracing).

But basically, things went smoothly – not unlike some master plan. That concept was brought up again and again when I discussed Queen with some of its associates. “They want to conquer the world” was how one person put it. For a group of this stature, a group that presumably has made enough money to last a lifetime, Queen maintains a very busy work schedule. After the release of The Game last June, the band did a major U.S. tour, recorded Flash Gordon and played some more dates in Europe and Britain. Then came the Japanese shows, the South American trek and a solo LP from Roger Taylor. This June they plan to begin work on another studio album, but before that comes out sometime next year, they will release a greatest-hits package (which reportedly will vary from country to country, depending on what songs have been hits in those areas).

Trending

Four years ago, in Queen’s last interview with Rolling Stone, Freddie Mercury said, “Our goal is to get to the top, obviously. We’re not there yet; nowhere near it. And I don’t want anybody to tell me I’m there either.” And the band still feels that way. When I asked them what they thought they’d be doing in five years, each member was convinced Queen would still be together, still reaching for something more. After all, you can’t conquer the world overnight.

This story is from the June 11th, 1981 issue of Rolling Stone.

#Roger Taylor#my little drummer love#well-read .. well-spoken#he says what he means and he means what he says#your periodic reminder that Roger is in no way stupid#Brian May#John Deacon#Freddie Mercury#Queen#Queen: Academia

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NAME: Margot Moore

NICKNAME(S): Mar

AGE: Thirty-three

BIRTHDAY: TBD.

GENDER IDENTIFICATION: Cis Woman (she/her)

SEXUAL ORIENTATION: Bi-curious

RELATIONSHIP STATUS: Single

RESIDENTIAL AREA:

OCCUPATION: Only Fans Model / Sex Worker

POSITIVE TRAITS: talented, strong, loyal

NEGATIVE TRAITS: closed off, stubborn, lost

PLACE OF BIRTH: Vancouver

Claire Moore dazzled the rink every time. She shined brighter than every other skater. She was written up in every newspaper as the world’s greatest figure skater. Age, marriage, children didn’t stop her, like others in her sport. She married a politician who wanted nothing more than to allow her dreams to continue to thrive.

After leaving winning gold in the Olympics and retiring, she traveled the world teaching classes, and starting workshops. Even when she was pregnant with her daughter, she pressed on. There was no doubt in anyone’s mind, from the minute Claire had Margot she was going to be a skater too. Much of her free time as a child was spent in classes – any and every class they could sign her up for. Margot lived in Vancouver most of the time with her nanny, while her mom worked all over the world and her father remained immensely buys.

When her mother was home, they trained together tirelessly. Margot’s summers were spent abroad – Russia, France, Amsterdam. She studied with the most prestigious couches. She was the daughter of a gold medalist so she could be nothing less than perfect. There was no room for anything else in her life. Skating was everything.

At 13, Margot went to the Olympics for the first time in Salt Lake. The buzz around her was endless. She was a name bubbling up in the community for years because of her mother and because of her talent. Margot took home silver that year. A disappointment to her mother, but an amazing feat in everyone else’s eyes. The next Olympic in Italy, she took home the gold.

In the years leading up to the 2010 Olympics hosted in her home town, she trained hard. Margot would be competing against younger fresher talent. It would be a dream come true to win gold in her home town. The night before her competition in the Olympics, Margot was rehearsing her routine full on skills deemed impossible. A fall caused her hip to shatter - pushing her into retirement before she even got to compete.

Margot returned home – settling into a depression because everything that had been planned for her had flown out the window. She retreated from society, not wanting to see much of people. Margot began to realize her whole life wasn’t her own. Nothing she ever did was things she wanted, but something she was born into. The entire time she was on bed rest, not able to even walk on her leg, her mother visited her once. Her father urged her to get the surgeries she needed to recover. Suddenly she was aware how little she meant to both without skating.

Through a series of fights, arguments, and everything in between – Margot told them she wanted nothing to do with them. She lost everything she’d ever known, leaving her with nothing. All of a sudden she needed to fend for herself, something she’d never had to do before.

She ran off to New York, trying to find herself in something, anything. It was the first time in her life she was truly free to be whatever. Margot picked up a job waitressing at a strip club. She watched as these women used dance in such a powerful way. One night after closing, she asked one of the women to show her some tricks on the pole. Margot still wasn’t physically ready to use her body like that again, but she seemed to find a new reason to want to be.

One of her coworkers introduced her to Only Fans. At first she was tentative, but once shown the ropes and how to make her own rules Margot felt more comfortable with it. Moving back here with nothing, she began to become pretty successful on Only Fans. She’s been home ever since.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My personal ranking for the Eurovision Grand Final:

Belgium: it's my favorite song. They definitely got fucked over by the sun's LED display not working, so the stage show is missing some of the imagery I think they wanted, but it's still absolute quality and one of the most technically difficult songs to sing. I'm hoping for a good jury result, but not much else :/

France: folktronica is one of those genres you basically only get at Eurovision and I love it. It's fun. It's culturally relevant. The stage show has a lot to look at. I adore this.

Spain: that choriography! And she's singing full out nearly the whole time!

Lithuania: love the vibes. Some songs get an audience singing and clapping. This one makes you sit down and shut up because you are too mesmerized to do anything else. Not many people talk about this one, but I think they should.

Serbia: if you saw the semifinal performance, you hear how thunderous the clapping was during the chorus. If this doesn't finish top 10, there will be riots.

Australia: pitch perfect vocal. Beautiful song. Beautiful message. Beautiful man in a beautiful dress. *chef's kiss*

Norway: it's fun, it's stupid, and I love it

Greece: beautiful song. I don't get the melting chairs but honestly, whatever.

Portugal: those harmonies tho.

Netherlands: not a lot to see in the stage show, but it's a very pretty song

Poland: his voice is great. The staging is a bit dark, but I like it anyway.

Czechia: fun song. Fun performance. She fixed up those vocals that had been off in the prepaties, and I'm happy to see this song in the final

Romania: it's fun. It's dancy. I like it.

UK: sorry to my one british mutual who is over the moon about this song. I'm not big on songs that are all falsetto like this. Gimme the range. This is comparatively low for personal taste reasons, but it is a good song and I do sing along when it is on.

Moldova: the song isn't amazing but they are having so much fun and I'm happy they qualified.

Estonia: not my genre but it's well done

Ukraine: still very uncomfortable about the two guys with the fake dreads. The song is catchy and well composed, but I just don't love it, and there are a lot of songs here that I do love. I expect them to finish on the left hand side, but this is where they are for me just evaluation the song and not the political context.

Sweden: nice enough, but I don't love her voice or the staging particularly. 0 idea why this is in the favorites to win, but here we are I guess.

Iceland: lovely and melo, but I do admit that I forget about it sometimes.

Azerbaijan: the staging elevates it a lot even if that first part gives me a knee-jerk "why would you lay down on the bleachers" reaction lol. I wouldn't have put them in the final, but they're here.

Armenia: this must be spectacularly boring to watch live, but the song is kinda cute.

Italy: those high notes just sound like so much work, and aparently the dress rehearsals have been a mess.

Germany: it's just a bit boring.

Finland: still find them annoying, but at least they are having fun.

Switzerland: do I even have to expain this one?

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes

Photo

Social and political destructives

The chief spirit of the social and political destructives was as obviously Rousseau as Voltaire had been the chief spirit of the religious destructives. Our business for the moment is with neither of these schools and with neither of these famous men. As all heterodoxy seemed to be latent in the mordant criticism of Voltaire, so all subsequent political anarchy seems to be concentrated in the morbid passion of Rousseau. But though Rousseau must be regarded as in all essentials a destructive, there are many ways in which he had a share in the constructive movement of ’89. In the splendour of his pleading for education, for respecting the dignity of the citizen, in his passion for art, in his pathetic dreams of an ideal simplicity of life, in his spiritual Utopia of a higher and more humane humanity, prophet of anarchy as he was, Rousseau has here and there added a stone to the edifice we are still building to-day.

When we turn to the constructive schools, there we find Diderot supreme in the intellectual world, Turgot in the political; whilst Condorcet is the disciple and complement of both. With the purely philosophical work of any of these three we are not now concerned. Our interest is entirely with the social and political question. And at first sight it may seem that Diderot has no share in any but the philosophical. But this most universal genius had a mind open to all sides of the human problem. His grand task the Eitcyclopddie (and we may remember that the first idea of it came from an English Encyclopaedia, which it was proposed to translate), the Encyclopedic is largely, and indeed mainly, concerned with economic and social matters. Throughout it runs the potent principle of the unity of man’s knowledge, of man’s life, and of the whole human race. Diderot does far more than discuss abstract questions of science. He traces out the ramifications of science into the minutest and humblest operations of industry private tour istanbul.

In the Encyclopaedia

In the Encyclopaedia we have installed for the first time on authority that conception of modern times — the marriage of Science with Industry. Machines, trades, manufactures, implements, tools, processes were each in turn the object of Diderot’s enthusiastic study. He and his comrades, men like Turgot, d’Alembert, Condorcet, felt that the true destiny of man was the industrial. They strove to place labour on its right level, to dignify its task, and to glorify its mission. Never had philosophy been greater than when she girt up her robes, penetrated into the workshop, and shed her light upon the patient toil of the handicraftsman. For the first time in modern history thought and science took labour to their arms. Industry received its true honour, and was installed in a new sphere. It was a momentous step in the progress of society as much as in the progress of thought.

Chief of all the political reformers, in many things the noblest type of the men of ’89, is the great Turgot; he, who if France could have been spared a revolution, was the one man that could have saved her. After him, Necker, a much inferior man, though with equally good intentions, attempted the same task; and the years from 1774-1781 sufficed to show that reform without revolution was impossible. But the twenty years of noble effort, from the hour when Turgot became intendant of Limoges in 1761 until the fall of Necker’s ministry in 1781, contained an almost complete rehearsal, were a prelude and epitome, of the practical reforms which the Revolution accomplished after so much blood and such years of chaos.

0 notes