#the subs seem to stick to a closer translation but i am very much enjoying some of the creative changes

Text

seimei: it's not like we'll ever see each other again bye

seimei: lmao can't believe you showed up after what you said

#netflix onmyoji#abe no seimei#minamoto no hiromasa#onmyojiedit#my gifs#utterly obsessed with some of the choices of the english dub#(not obsessed (derogatory) btw. legitimately obsessed)#the tiny change to have hiromasa ask if seimei is going to be like this 'all the time now.' implying that he's already planning their futur#is as the kids say#chefs kiss#i generally watch the subs but i am having fun checking out the dub for the scenes i gif#the subs seem to stick to a closer translation but i am very much enjoying some of the creative changes#yes the way they choose to format the names is distressing but whatever#anyway these scenes have so much in them#seimei goes from teasing flirting to 'bye cute nice guy lets talk never'#and then pretends the next time like it was hiromasa's idea the entire time#and hiromasa is so flustered he lets him get away with it#good stuff good stuff#missing scene fic where seimei doesn't show up on purpose because he's waiting hoping yearning for hiromasa to show up and ask him#also the adorable smile in the first gif i'm never over it

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chinese Company Retreat

You can usually tell a Chinese tourist destination’s degree of development and sophistication by just reading the English translations on its sign boards posted along the sight-seeing paths. The closer to Standard English the translations on these notices are, the more highly developed the site is. Or put another way: the more random the English translations are on these public announcements, the more second- or third-rate the site is. Why is that so? Either the place doesn’t have the resources to put proper English on its signage, or so few international tourists go there that their laughter at seeing garbled English messages never reaches a critical threshold that would compell a change.

Judged by the level of English public service announcements, Moganshan Mountain resort in Zhejiang Province leaves some things to be desired.

“Carefully slip. Pummeling” or “Meet in front of care” are not instructions that English-speakers can easily follow. From this we can deduce a somewhat diminished status of this place. It was not always thus. Not too long ago, Moganshan was a swanky hill station that Shanghai’s moneyed classes sought out in droves, an equivalent of India’s fabled resort town of Simla.

Moganshan is located at the end of long and winding road that ascends gradually to about 700 meters from the flats of the Yangtze River Delta. Here, portly Western mansions and posh villas had been built, mostly by foreigners, with gains from trade, drugs, and financial investments in not-so-distant Shanghai. However, the invention of air conditioning has put a serious crimp into the attractiveness of this hill station. Fewer people nowadays travel hours outside of Shanghai during the summer months just for the chance to catch a cool breeze; instead, they are more likely to reach for the AC remote control in their well-appointed downtown apartments. The problem with Moganshan is that besides the slightly cooler air in summer, it does not have that much else to offer. The scenery there is a far cry from the picturesque sites like Huangshan, only an hour or two further up the road.

Basically, one just sees gently undulating hills, if the view is not totally obstructed by tall bamboo, which grows riotously on these mountains. In fact, bamboo is being actively harvested on the mountains here, and if you see bamboo scaffolding on a building in Shanghai, the bamboo likely comes from here.

Although tourist busses still arrive on good days in summer, and although the place is rated as AAAA by China’s tourism board (no place I’ve ever been to was rated less than four-A), a whiff of decline hangs around the town. Something is slowly crumbling in this place, and it’s not just the stairs that lead from the town’s main square to the lodge where we stayed, making for treacherous footing. The place’s online footprint is somewhat sub-par, too: I searched back and forth for a hiking map or trail guide online, but apart from a few scattered blog entries by individuals, there was nothing “official” available.

But the lack of spectacular sights has its benefits: there are no crowds bustling you on every square inch, no selfie-sticks that you have to duck constantly, no echo enabled loudspeakers blaring from tour guides left and right, and no shuttle busses into which you are herded like cattle. It is a quiet, quaint, down-at-heels sort of faded-glory resort town that is trying to charm the few tourists coming its way, especially during off-season, with personal attention and genuine hospitality, both of which are available in spades.

And anyway, we had come to Moganshan not so much to enjoy the scenery, but to conduct a retreat of a multinational pharmaceutical start-up company that I’m connected to through Liang. For that purpose, the sleepy town was very suitable. We were quartered in a charmingly, if somewhat do-it-yourself, upgraded lodge that made genuine efforts to cater to urban audiences. Some of the Spartan bedrooms were equipped with handsome wrought-iron bed frames, there was nice local artwork on the walls, and the tiny bathrooms were westernized with sitting toilets and rainfall shower heads. The house was about 1 degree above freezing when we arrived, but as soon as we crossed the threshold, the blowers in the cold bedrooms were cranked up and a blazing fire was started in a wood burning stove in the lobby. The Chinese are very reasonable about preserving their resources that way. If entering a cold lodge that warms up only after one’s arrival means heightened sustainability, then count me in.

Soon, it was time for lunch, which the whole group was more than ready for. Elevation and crisp temperatures always make for a keen appetite. We enjoyed chicken soup from locally grown fowl, thick with oil naturally extracted from the succulent meat. There was a mysterious lamb-like meat on small bones that turned out to be wild boar hunted on these hills, slowly cooked in a dark, plummy broth. There were several dishes built on the staple that puts its stamp on the whole area—bamboo: Bamboo with chicken, bamboo with pork, bamboo with wood-ear fungus, bamboo with bean curd, and even the beer was said to be made with bamboo. How that can be is beyond my imagination, but the folks reassured me that somehow bamboo had been worked into the beer.

Among the 14 people participating at the retreat, I was the only Westerner, which meant that this was a great Chinese immersion experience for me. I occasionally followed what was going on during the conversations, and I got in a word or two as well, thus confirming my slow upward trajectory in learning Chinese.

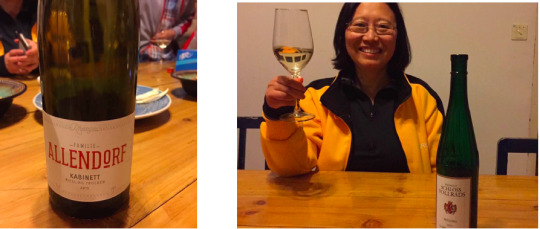

A company retreat like this, complete with alignment exercises, brainstorming discussions, break-out sessions, and strategy roundtables would not be complete without a dinner that involves unlimited quantities of liquor. We started things at the lodge over cheese, preserved meats, and dried fruit, accompanied by bottles of fragrant, light-bodied German Riesling, which two members of the company had personally brought with them from Germany.

Then it was time for dinner in a nearby restaurant. The local, bamboo-infused beer appeared again on the table, but the protagonist among the alcoholic beverages was “bái jiǔ” or grain liquor.

This heady distillate strikes the Western palate as strangely flavored. There are notes of sour hard-candy, pungent lily scents, and cabbage aromas, to name just some of the cascading layers of tastes. But this stuff is potent, and I limited myself to the tiny thimble glasses that can only be found in China.

One of the reasons for this is the Chinese drinking tradition of “gambei,” which means “bottoms up,” and the folks here usually hold you to the literal meaning of it. The command “gambei!” is heard every few minutes at an authentic Chinese banquet, and after draining your glass, you are then expected to demonstrate that you have touched bottom by holding the glass upside down for all to see. That’s when the small size of the glasses can be a life-saver.

Some of the more serious drinkers at the table soon switched their thimbles for water glasses, and this is when I got a bit concerned, especially after I saw them draining said glasses at regular intervals. I am not a bad drinker, but my capacity was dwarfed by the amount of grain liquor these men (I did not see women drink quite as much) could guzzle without loosing their cool. It helped that there were 20 dishes accompanying the drink, absorbing some of the alcohol. So, everybody ate their fill and, to various degrees, drank their fill.

The conversation never flagged, just as I remarked on my previous post about a dinner hosted by the same company in Shanghai. And again I had a chance to notice that the Chinese love to laugh. It is a hearty, good natured, reverberating laugh that shakes the walls. The jokes must have been good because the results were tremendous, although I often could not follow the gist of the conversation in Chinese. All this alcohol had loosened tongues to the point where speech became rapid and speaking turns overlapped. Sometimes, it seemed as if the group was building a collective joke, involving all in the gradual architecture of the jest. For instance, somebody started the idea that one of the women present was going to give a speech that would make another person tear up, and in anticipation of this, the announcer started to hand out paper tissues to the butt of the joke, as well as to other select participants. The other diners cheered this on, thus building the anticipation, and when the woman gave her speech—which seemed to produce exactly the anticipated result—the laughter rose in a chorus that made me anxiously eye the windows which separated us from the frigid mountain air, looking for cracks.

Anyway, proceedings came to an end about 2 hours after dinner had started, at which point we walked back to the lodge. There, at a communal table in the kitchen, waited two bottles of Dewar’s Scotch Whiskey and three bottles of full-bodied reds.

I was glad I had paced myself with the rice wine at dinner, so I still had some capacity to enjoy a spectacular Bordeaux (Pauillac 2009), which we finished easily with some cheese and crackers. The hard-drinkers of the company were keeping pace with me, making me wonder once again, how they could tolerate this much drink. Heavy drinking is part of how business is conducted in China: you drink with your business associates or company employees to the breaking point, almost a bit like at a frat party, except that people usually don’t pass out here. By doing so, you demonstrate your ability to hold your liquor, which confers social capital. You also signal that you are relating to others on a basic, primordial level of conviviality, outside of conventional politeness rules. It is certainly a bonding experience, but not one that I can emulate. To be drunk on Chinese grain liquor is not a feeling I cherish, and I cannot fathom what makes it so appealing to others. To my surprise, the following morning, I saw no visible signs of a hangover. Everybody showed up bright and collected, no shades under the eyes, no headaches… Beats me.

Anyway, the retreat had definitely fulfilled its purpose of improving inner-company communications and building “esprit de corps.” That this took place in a declining, sleepy, off-season resort town only added to the success of the event. After all, the real business at hand—to unite all members of the company behind the firm’s short term and long-term goals—was the central objective of the event, not to be dwarfed by spectacular scenic “distractions” outside the window. It was a bit like a New York company holding a retreat in Mount Pocono—an OK place but nothing outstanding, and with a whiff of bygone grandeur hanging around it. However, the place also held an apt symbolic implication: indeed, Moganshan represented just the antithesis of what this fledgling, start-up company wants to be. The company, of course, doesn’t aim to be a Moganshan (or a Mount Pocono) but a Huangshan (or a Whistler). In other words, it doesn’t want to be a dated, nostalgic entity resting on its laurels but a forward-looking, dynamic trend-setter with charisma. So, when the company left Moganshan, it left it in more senses than one. It had become an anti-Moganshan outfit, an enterprise whose future is bright, open, and exciting—and whose English communications are quite flawless.

1 note

·

View note